Abstract

Inherited bleeding disorders are not uncommon in pediatric practice: most of them being chronic, require lifelong replacement therapy. To frame a management policy, it is essential to assess the load and pattern of bleeding disorders in the local population. However, there is paucity of data reporting the clinical spectrum of coagulation and platelet function disorders in Indian children. Hence to find out the exact burden and clinico-investigational profile of these patients we conducted this study. In this retrospective case review, detailed clinical information was extracted from case records in 426 children with a suspected diagnosis of hereditary bleeding disorder registered in the Pediatric Hematology clinic of a tertiary referral centre over a period of 14 years (1998–2011) and pooled for analysis. In our cohort prevalence of hemophilia A, hemophilia B, platelet function disorders, von Willebrand disease and other rare factor deficiencies were 72%, 11%, 7%, 4% and 4% respectively. Common clinical spectrum included skin bleeds, arthropathy, mucosal bleeds. 10% had deeper tissue bleeding and 16% received replacement therapy at the first visit. Nearly 3/4th of cases were lost for follow up after the initial visit. Hemophilia A was the commonest inherited bleeding disorder in our population. Skin bleeds and arthropathy were common clinical presentations. Factor replacement therapy was restricted to a minority. There is an urgent need for establishing centres of excellence with administrative commitment for factor replacement therapy for comprehensive management of such children in resource-limited countries.

Keywords: Bernard soulier syndrome, Glanzmanns’ thrombasthenia, Hemophilia, Inherited coagulation disorders, von Willebrand disease, Inherited bleeding disorder, Children, Platelet function defect

Introduction

Pediatricians deal with inherited bleeding disorders in day to day practice. In absence of a background knowledge of local prevalence and clinical features of these disorders, establishing a definite diagnosis and timely management is often challenging. Though South-east Asia is home to half of the world's pediatric population, studies regarding epidemiological profile of inherited bleeding disorders especially from pediatric age group are few from this region: most of the available data is often extrapolation of available literature from developed world.

The proportion of various bleeding disorders from middle eastern countries (Iran, Jordan and from Pakistan) from hospital based studies varies between 26–74%, 6–17%, 12–22% and 7–28% for hemophilia A (HA), hemophilia B (HB), platelet function disorders (PFD) and von-Willebrand factor (vWD) respectively [1–5]. Higher prevalence in the population has been reported in areas where consanguinity is common. India being a diverse mix of different cultures and races has a unique mix of the bleeding disorders. Most of the literature pertaining to the bleeding disorders available from Indian subcontinent, is based on a mixed population comprising both adult and children or purely adult populations [6–9]. There is a wide variation of reported proportion and clinical manifestation of inherited bleeding disorders among these studies: majority reporting hemophilia, von Willebrand disease and platelet function defects as the common ones. Studies regarding platelet function defects are even less.

Therefore, we planned to study epidemiological, clinical and laboratory profile in a retrospective cohort of children with inherited bleeding disorder visiting our hospital.

Methodology and Study Population

In this retrospective study, data were collected retrospectively from the patient case records from 1998 to 2011 (14 years) over a period of 2 year (2010–2011). Confidentiality of data was maintained and institutional ethical committee clearance was obtained. Information was recorded on a pre-designed performa, which included detailed demographic profile, clinical features, laboratory profile, treatment received, follow up and outcome measurements. Complete blood count with peripheral smear, platelet count, prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) were done in all cases of suspected bleeding disorder and depending on the above test results, mixing studies, correction studies, factor assays (in this sequence) and platelet aggregation tests were done to confirm the diagnosis.

The complete blood count was done on automated haematology cell counters. Measurement of PT, aPTT and fibrinogen level were performed by an automated coagulation analyser (STA Compact, Diagnostica Stago, France) after 2004, and manually prior to that. The reference values for PT, aPTT and fibrinogen were 12–16 s, 27–32 s and 2–4 g/L, respectively [10, 11]. A prolonged clotting time test was followed by a mixing study utilizing normal plasma, adsorbed plasma, aged plasma and specific factor deficient plasma as applicable. Individual clotting factor assays were performed as per the results of mixing studies. The severity of disease for haemophilia A or B was classified as mild (factor level: 5–30%), moderate (factor level: 1–5%) or severe deficiency (factor level: < 1%). After a lab diagnosis of haemophilia was confirmed by coagulation studies, postnatal genetic analysis was carried out in all cases (wherever possible) and the mothers of affected children were also advised for antenatal diagnosis in future pregnancy.

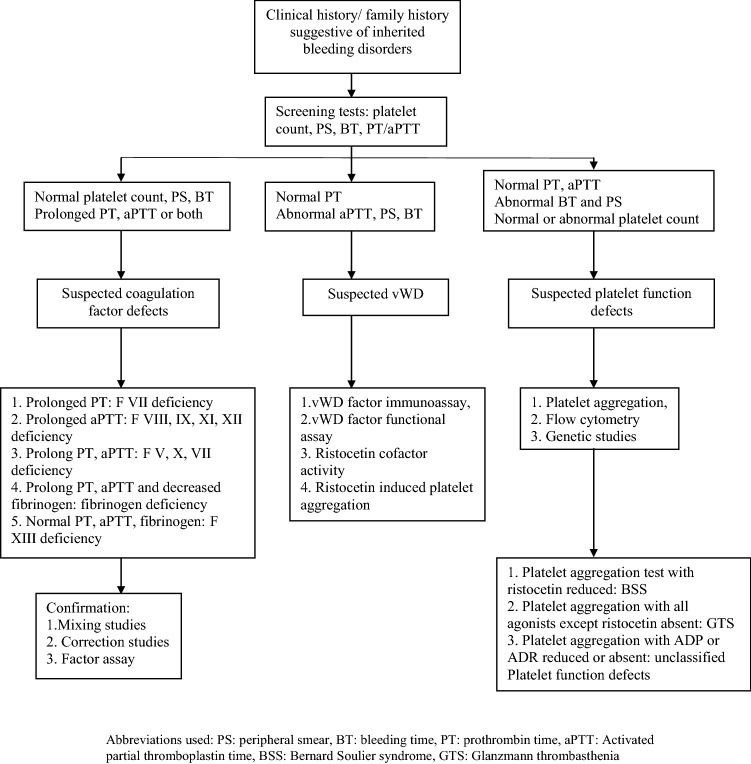

In suspected platelet function disorders, light transmission platelet aggregation studies were performed using platelet aggregometer, Chrono log, Model 700: adenosine diphosphate (1.25 and 2.5 µmol/L), arachidonic acid (500 µmol/L), adrenaline (10 µM), collagen (2000 µg/L), ristocetin (1 mg/mL). In the absence of data on normal healthy population on children from North India, the standard reference values for platelet function tests, aggregation amplitudes of < 50% as compared to that in normal controls were used to define impaired platelet aggregation. Where ever possible, abnormal results were reconfirmed by repeat testing. Apart from platelet aggregation studies, newer studies like vWD antigen assay, Ristocetin cofactor activity were used in later part of study period for classifying type of vWD. Similarly, flocytometry study for evaluation of expression of CD41, CD42 and CD61 were introduced in recent years. However, vWD multimer assay (for subtyping of type 2) as well as immune-phenotyping for confirmation of diagnosis of Bernard Soulier syndrome could not be possible. Figure 1 depicts flow chart on sequence of investigations followed in the unit in children with suspected inherited bleeding disorder.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of investigations after clinical suspicion of bleeding disorder

On follow up, routine inhibitor screening was not used in our institute and it was restricted to cases who received regular prophylactic factor transfusion or those cases who did not respond to FFP/factor transfusion.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 17 software using relevant descriptive statistics which included mean, standard deviation, median, mode, proportion and range.

Results

Of the 673 children enrolled in the Pediatric Hematology Clinic with various inherited bleeding disorders, 247 were excluded in view of (i) incomplete records; (ii) change of final diagnosis during follow up; and (iii) non-establishment of any diagnosis. There were 82 patients with prolonged APTT in whom the diagnosis of HA or HB could not be established because of failure to report for further testing. Finally, 426 children were included in analysis.

The median (IQR) age of study cohort was 3.0 (1.1, 6.5) years respectively. Overall sex ratio was 17.5:1 (403 males and 23 females). The median (IQR) age of patients at presentation with HA, HB, vWD and PFD were 3.0 (1.0, 6.5) years, 2.5 (1.3, 6) years, 5.0 (3.0, 9.0) years and 5.0 (2.0, 7.2) years respectively. For severe vWD, the male: female ratio was less skewed i.e. 1:1 (10 male and 9 female). In the Platelet function disorder group, which included Bernard Soulier Syndrome (BSS), Unclassified PFD and Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia (GTS), the gender ratio was 1.5:1 (19 males and 13 female). Factor X deficiency was diagnosed in six cases (two females). We had a 2 and ½ year girl from Muslim community with strong family history but without consanguinity suffering from hemophilia A.

The commonest bleeding disorder was HA occurring in 72% of all cases. It constituted 82.1% of all coagulation defects referred to our center. HB constituted 11.5% of all bleeding disorders and 13% of all coagulopathies. Factor VIII assay was available in 112 (36.3%) HA patients, of which 73 (23.7%) had severe factor VIII deficiency. Similarly, results of Factor IX assay were available in 15 (30%) HB patients and of these 13 cases (86.7%) had severe factor IX deficiency. Deficiencies of other rare coagulation disorders were seen in 18 cases (Table 1). Majority of the patients with rare factor deficiency had milder bleeding manifestations as compared to HA and HB.

Table 1.

Distribution of patients with hereditary bleeding disorders

| Inherited bleeding disorders | No. of patients, n (%) N = 426 |

|---|---|

| Hemophilia A | 308 (72.3) |

| Hemophilia B | 49 (11.5) |

| von Willebrand disease | 19 (4.4) |

| Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia | 19 (4.4) |

| Bernald Soulier disease | 3 (0.7) |

| Unclassified platelet function defects | 10 (2.2) |

| Factor II deficiency | 2 (0.47) |

| Factor V deficiency | 5 (1.1) |

| Factor VII deficiency | 1 (0.23) |

| Factor X deficiency | 6 (1.4) |

| Factor XIII deficiency, severe type | 4 (0.9) |

PFDs were present in 7% of patients analyzed. GTS was the commonest constituting 4% of total bleeding disorder (n = 19) and 59% of total platelet function disorders. Confirmatory tests like immunocytochemistry and flowcytometry for GTS could be performed in 3 cases each. In ten cases of PFD, the exact characterization was not done and these were grouped as unclassified PFD. Three cases of Bernard Soulier syndrome were present in whom we could not perform flow cytometry. Family history was positive in 55% cases of HA, 47% of HB and 32% of PFD and in 51% of all cases analyzed. A history of previously affected sibling was present in 24.9% (HA/HB), 21% (VWD) and 25.8% (PFD).

Clinical features

Hemophilia Group (Table 2)

Table 2.

Major clinical sites of bleed in hemophilia A and hemophilia B

| Site of bleed | Total (N = 357) n (%) |

Hemophilia A (N = 308) n (%) |

Hemophilia B: (N = 49) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral mucosal bleed/gum bleed | 119 (33.3) | 99 (32.2) | 20 (40.0) |

| Ecchymosis/purpura | 264 (73.9) | 223 (72.6) | 41(82.0) |

| Joint bleed | 120 (33.6) | 100 (32.6) | 20 (40.0) |

| Intracranial | 10 (2.8) | 7 (2.3) | 3 (6.0) |

| Gastro-intestinal bleed (hematemesis/Malena) | 15 (4.2) | 13 (4.2) | 2 (4.0) |

| Epistaxis | 17 (4.8) | 13 (4.2) | 4 (8.0) |

| Intra-abdominal bleed | 7 (2.0) | 7 (2.3) | Nil |

| Umbilical cord bleed | 6 (1.6) | 5 (1.6) | 1 (2.0) |

| Circumcision bleed | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | Nil |

Out of all bleed types, 45.4% (162) were post traumatic: 43.3% (133) in HA and 58% (29) in HB

Ecchymosis (73%), was the most common presenting symptoms in cohort. Joint bleeds were the next most common manifestations observed in 120 cases involving pressure bearing joints like knee and ankle. The knee joint was the commonest joint involved in 62 cases (51.66%) followed by elbow joint in 10 (6.6%) cases and ankle joint in 7 (5.8%) cases. In 38 cases multiple joints were involved. Small joint involvement was rare; 2/120 had involvement of small joints of hands. Temporo-mandibular joint involvement was seen in a single patient with HB. Oral mucosal bleed was third most common found in 33% of total hemophiliacs.

Intracranial bleed was observed in 10 cases (2.8%). The bleeds were subdural, intra-parenchymal, intraventricular and subarachnoid in location. One of the patients with hemophilia B had an intracranial bleed with hematomyelia, later resulting in quadriparesis. Apart from the above, bleeding was also seen in uncommon sites like intra-orbital (2 cases), intrathoracic (2 cases), scrotal hematoma (2 cases) and isolated hematuria (9 cases). Of the two cases of intra-orbital bleed, one had permanent visual loss on follow up. Intramuscular bleeds were documented by ultrasonography in 9 cases, the psoas hematoma being the commonest.

von Willebrand Disease and Platelet Function Disorders

Clinical manifestations of platelet function disorders and vWD closely mimic each other. A comparative picture of clinical features of these is depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of sites of bleeding in von Willebrand disease (vWD) and other platelet function disorders (PFD)

| Clinical features | vWD group (n = 19) | PFD group (n = 32) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of patients | % | No of patients | % | |

| Oral mucosa/gum bleed | 11 | 57.9 | 18 | 56.2 |

| Ecchymosis | 13 | 68.4 | 21 | 65.6 |

| GI bleed | 3 | 4.6 | 1 | 3.1 |

| Epistaxis | 7 | 36.8 | 13 | 40.6 |

Out of all bleed types 42.1% (8) in vWD and 25% (8) in PFD group were secondary to trauma

Treatment Modalities

Replacement therapy was given in the form of Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) in 14.3% of hemophiliacs during first admission, while factor replacement and cryotherapy were administered in ten cases and three cases respectively. As state government supported free of cost, factor replacement therapy is not available at our institute, prophylactic factor replacement therapy was not routinely practiced in our center. They were occasionally used for children whose parents were entitled for reimbursement from their employer. Minor mucosal bleeds in mild hemophiliacs as well as VWDs were managed with local application of tranexamic acid or IV desmopressin. In addition, 4.5% of hemophiliacs also received Packed RBCs to correct the anemia caused due to blood loss. The rare factor deficiencies were mostly treated with fresh frozen plasma or cryoprecipitate.

Disease Course

Follow up data was available in 32% of cases; rest opting for treatment at centres closer to their residence or lost to follow up due to inadequate finances. The mean duration of follow up, for those patients who revisited, was 4.4 years, the longest period being 9 years. Chronic hemophiliac arthropathy was the most common cause of morbidity in hemophilia patients affecting 18.8% of all cases of hemophilia. Three cases had transfusion transmitted disease: two cases of hepatitis B and a single case of hepatitis C. In an isolated case of hemophilia A, inhibitor was detected. Four of the patients died in hospital due to bleeding related complications like hypotensive shock, raised ICP secondary to Intracranial hemorrhage: one case each of vWD and of HA and 2 cases of HB.

Discussion

In our study hemophilia was most prevalent bleeding disorder followed by platelet function disorder and vWD. Common sites of bleeding were mucocutaneous and hemathrosis. Hemophilic arthropathy was the commonest chronic morbidity. Therapy with fresh frozen plasma being most frequently used therapy modality with factor replacement therapy used only in a smaller fraction. Majority of the patients were lost to follow up after first visit. Prevalence of inhibitors as well as transfusion transmitted infection was relatively less.

Similar to available literature from Indian subcontinent [6, 8, 9, 12, 13] as well as middle east Asia [2] and Pakistan [5, 14], our study showed hemophilia A to be the commonest bleeding disorder. GTS was the most common PFD in our case in contrast to previous studies conducted on PFD in Indian subcontinent [8, 12, 13] which showed isolated platelet factor 3 (PF3) deficiency as the most common. This difference is likely to be a result of divergent testing practices for bleeding disorders in different centres. For example, in some regional centers including ours, the test for detecting PF3 deficiency is not included the routine test panel for bleeding diathesis.

Although vWD is the commonest reported coagulation defect with 1% incidence in population-based studies [15], it is not so in hospital-based studies like ours, as a large proportion of vWDs having minor bleeds do not receive medical attention and hence not reported. Also, menorrhagia though a common manifestation of VWD in females, is less common in our study population which was confined to pre-pubertal pediatric age group: the mean age (SD) of the girls being 5.9 (3.5) years. As per Gupta et al., vWD was less common as compared to PFD (16.7% vs. 35.6%) which was also the case in our study (7.5% vs. 4.4%) [14].

An unusual case of hemophilia A in a girl in our cohort is clinically assumed to be due to Lyon’s hypothesis with skewed X-chromosome inactivation which has been reported previously [16–19]. Although we did rule out severe variety of vWD, we could not do confirmatory genetic analysis for lyonisation. Similarly, coexistence of HA and congenital generalized ichthyosis (both are X linked) in one of our patients may be explained by the hypothesis of contiguous gene deletion which have been reported rarely [19].

Absence of a family history in nearly half of hemophilia patients in our study suggests the sporadic nature of disease as a result of spontaneous genetic mutation. Nearly 2/3rd of all hemophilia who underwent factor assay had severe disease suggestive of prevalence of severe hemophilia in the North Indian population, although referral bias due to earlier presentation of severe cases to health care facility can be another reason. A similar picture is available from other hospital based population data analysis [8, 15].

The prevalence of chronic arthropathy in our hemophilic population (18.8%) was somewhat higher (8.5%) as reported from in Pakistan [5], but similar to that from China [20] and Iran [2]. This may be attributed to a variety of factors i.e. high prevalence of severe hemophilia in Indian population, delayed presentation to hospital due to lack of awareness, inadequate replacement therapy as well as prophylaxis and the hospital based nature of the current work.

In current study, the incidence of PFD and vWD was found to be low (7.5% and 4.4% respectively) as compared to the previous studies which reported incidence of PFD and vWD from 12.8 to 39.4% [9, 14] and 6.5 to 20% [2, 5] respectively. Our PFD prevalence is similar to the previous adult population studies from our Institute [21] and Western India [22]. One possible explanation for low incidence could be that PFD and vWD are autosomal disorders and have been found to have higher incidence in communities where consanguinity is common. The consanguinity in our study population was low (4.5%) as compared to national level (10.6%) [23].

The low numbers of patients receiving replacement treatment is due to underreporting and may not be the actual representation of the consumption of health resources at our Institute and as well of the resources used by the bleeding diathesis patients in their life time, as most of these patients were advised to be followed up at nearby health care centers for minor bleeds and replacement therapy. Unlike many other states in India, factor replacement therapy is not freely available in our institute; thus utilization of factor replacement therapy is quite low and restricted to those children whose parents were entitled for reimbursement from their respective employers for the same.

Transfusion transmitted infections are one of most important iatrogenic complications in bleeding disorders [20, 24, 25]. The incidence of transfusion transmitted disease (3 cases) is low as compared to all India level in general population as well as in transfusion dependent population [26–29], which is probably due to lack of frequent testing especially in the patients who opted out of follow up for financial or logistic reasons. Also lack of routine serological screening for hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV in pediatric patients may also contribute to under diagnosis.

Incidence of development of inhibitors is less as compared to studies from adult population (6%) [30–32]. Inhibitors in children are less common as compared to adults. Some other contributory factors in our set up are less exposure to replacement therapy viz. plasma or FVIII, due to poor access, availability or exorbitant cost of therapy as well as lack of implementation of routine screening tests for inhibitors in multi-transfused patients. The state-aided provision of replacement therapy, now in place in some Indian states, is likely to change this situation, making it imperative for routine inhibitor screening for improving outcomes.

Our study provided basic demographic and clinical features in inherited bleeding disorders in the children from North India with a reasonable large sample. The main limitation of our study was retrospective nature of study, higher number of cases lost to follow up and absence of long term follow up data. Also, we could not perform some advance studies like investigation for subgroup typing of vWD type II, immune-typing for confirmation of diagnosis of BSS, due to lack of appropriate facilities for the same. There is a bias in under estimation of true prevalence of these disease in community due to selective referral.

Conclusions

Our study shows that inherited disorders are not uncommon in children investigated for bleeding: hemophilia A being commonest. Chronic arthropathy remains major cause of morbidity and stresses the need for comprehensive joint care in the affected children. The currently underreported incidence of inhibitors draws attention for improving existing screening for these in multi-transfused children by having more of such centres especially in the non-urban areas.

Author’s Contribution

TS: Developed study protocol, implemented the study and wrote the first draft of the paper. SN, JA, RKM, AT, DB: Contributed in writing manuscript and providing critical feedback. DB: Guarantor of the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethics approval

Institutional ethics committee permission was obtained for this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Awidi AS. Congenital hemorrhagic disorders in Jordan. Thromb Haemost. 1984;51(3):331–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karimi M, Yarmohammadi H, Ardeshiri R, Yarmohammadi H. Inherited coagulation disorders in southern Iran. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph. 2002;8(6):740–744. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2002.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Bostany EA, Omer N, Salama EE, El-Ghoroury EA, Al-Jaouni SK. The spectrum of inherited bleeding disorders in pediatrics. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis Int J Haemost Thromb. 2008;19(8):771–775. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32830f1b99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansouritorghabeh H, Manavifar L, Banihashem A, Modaresi A, Shirdel A, Shahroudian M, et al. An investigation of the spectrum of common and rare inherited coagulation disorders in north-eastern Iran. Blood Transfus Trasfus Sangue. 2013;11(2):233–240. doi: 10.2450/2012.0023-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sajid R, Khalid S, Mazari N, Azhar WB, Khurshid M. Clinical audit of inherited bleeding disorders in a developing country. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53(1):50–53. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.59183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta PK, Charan VD, Saxena R. Spectrum of von Willebrand disease and inherited platelet function disorders amongst Indian bleeders. Ann Hematol. 2007;86(6):403–407. doi: 10.1007/s00277-006-0244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trasi S, Shetty S, Ghosh K, Mohanty D. Prevalence and spectrum of von Willebrand disease from western India. Indian J Med Res. 2005;121(5):653–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmad F, Kannan M, Ranjan R, Bajaj J, Choudhary VP, Saxena R. Inherited platelet function disorders versus other inherited bleeding disorders: an Indian overview. Thromb Res. 2008;121(6):835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shetty S, Shelar T, Mirgal D, Nawadkar V, Pinto P, Shabhag S, et al. Rare coagulation factor deficiencies: a countrywide screening data from India. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph. 2014;20(4):575–581. doi: 10.1111/hae.12368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis S, Bain B, Baitd I. Dacie and Lewis practical haematology. 10. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2006. pp. 380–440. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachmann F. Diagnostic approach to mild bleeding disorders. Semin Hematol. 1980;17(4):292–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saraya AK, Saxena R, Dhot PS, Choudhry VP, Pati H. Platelet function disorders in north India. Natl Med J India. 1994;7(1):5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quiroga T, Goycoolea M, Panes O, Aranda E, Martínez C, Belmont S, et al. High prevalence of bleeders of unknown cause among patients with inherited mucocutaneous bleeding. A prospective study of 280 patients and 299 controls. Haematologica. 2007;92(3):357–365. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta M, Bhattacharyya M, Choudhry VP, Saxena R. Spectrum of inherited bleeding disorders in Indians. Clin Appl Thromb Off J Int Acad Clin Appl Thromb. 2005;11(3):325–330. doi: 10.1177/107602960501100311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Werner EJ, Broxson EH, Tucker EL, Giroux DS, Shults J, Abshire TC. Prevalence of von Willebrand disease in children: a multiethnic study. J Pediatr. 1993;123(6):893–898. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Windsor S, Lyng A, Taylor SA, Ewenstein BM, Neufeld EJ, Lillicrap D. Severe haemophilia A in a female resulting from two de novo factor VIII mutations. Br J Haematol. 1995;90(4):906–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb05213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seeler RA, Vnencak-Jones CL, Bassett LM, Gilbert JB, Michaelis RC. Severe haemophilia A in a female: a compound heterozygote with nonrandom X-inactivation. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph. 1999;5(6):445–449. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.1999.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoyer LW. Hemophilia A. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(1):38–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401063300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capra R, Mattioli F, Kalman B, Marcianò N, Berenzi A, Benetti A. Two sisters with multiple sclerosis, lamellar ichthyosis, beta thalassaemia minor and a deficiency of factor VIII. J Neurol. 1993;240(6):336–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00839963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Li H, Zhao H, Zhang X, Ji L, Yang R. Retrospective analysis of 1312 patients with haemophilia and related disorders in a single Chinese institute. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph. 2003;9(6):696–702. doi: 10.1046/j.1351-8216.2003.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garewal G, Ahluwalia J. Platelet function disorders. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70(12):983–987. doi: 10.1007/BF02723825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manisha M, Ghosh K, Shetty S, Nair S, Khare A, Kulkarni B, et al. Spectrum of inherited bleeding disorders from Western India. Haematologia (Budapest) 2002;32(1):39–47. doi: 10.1163/156855902760262754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bittles AH. Endogamy, consanguinity and community genetics. J Genet. 2002;81(3):91–98. doi: 10.1007/BF02715905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee CA. Transfusion-transmitted disease. Baillières Clin Haematol. 1996;9(2):369–394. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(96)80069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chuansumrit A, Krasaesub S, Angchaisuksiri P, Hathirat P, Isarangkura P. Survival analysis of patients with haemophilia at the International Haemophilia Training Centre, Bangkok, Thailand. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph. 2004;10(5):542–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2004.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borhany M, Shamsi T, Naz A, Khan A, Parveen K, Ansari S, et al. Congenital bleeding disorders in Karachi, Pakistan. Clin Appl Thromb Off J Int Acad Clin Appl Thromb. 2011;17(6):E131–E137. doi: 10.1177/1076029610391650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meena M, Jindal T, Hazarika A. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus among blood donors at a tertiary care hospital in India: a 5-year study. Transfusion (Paris) 2011;51(1):198–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Datta S. An overview of molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in India. Virol J. 2008;5:156. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panda M, Kar K. HIV, hepatitis B and C infection status of the blood donors in a blood bank of a tertiary health care centre of Orissa. Indian J Public Health. 2008;52(1):43–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wight J, Paisley S. The epidemiology of inhibitors in haemophilia A: a systematic review. Haemoph Off J World Fed Hemoph. 2003;9(4):418–435. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2003.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinto P, Shelar T, Nawadkar V, Mirgal D, Mukaddam A, Nair P, et al. The epidemiology of FVIII inhibitors in Indian haemophilia A patients. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus Off J Indian Soc Hematol Blood Transfus. 2014;30(4):356–363. doi: 10.1007/s12288-014-0342-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubey A, Verma A, Elhence P, Agarwal P. Evaluation of transfusion-related complications along with estimation of inhibitors in patients with hemophilia: a pilot study from a single center. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2013;7(1):8–10. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.106714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]