Abstract

There is an increasing interest in the possibility of storing platelet concentrates below standard temperatures. The role of 14–3–3 proteins has been demonstrated in numerous cellular functions, including both its positive and negative roles in apoptosis. The 14–3–3ζ protein has a potential role in regulation of storage induced apoptosis in platelets. Apheresis platelets were collected and stored under either at room temperature (RT, 20–24 °C) or cold temperature (CT, 2–6 °C) conditions (n = 7 in each group). Flow cytometry was used to assess changes in phosphatidylserine and mitochondrial membrane potential in washed platelets. Proteomic changes were analyzed using Western blot and coimmunoprecipitation. During RT storage conditions used in this study, we found that both Annexin V and JC-1 exhibited significant increases at Day 3 compared to Day 1. In comparison to RT storage, a 3-day cold storage exhibited higher positive rates of Annexin V and lower positive rates of JC-1. The release of cytochrome c and caspase 3 and 9 cleavage were only observed in platelets maintained under RT storage conditions for 3 days. The anti-apoptosis protein Bcl-xL was downregulated and the pro-apoptosis protein Bak was upregulated under RT storage conditions. However, both Bcl-xL and Bak of CT-D3 exhibited no significant changes in comparison to either RT-D1 or CT-D1. Expression levels of 14–3–3ζ and GPIbα decreased significantly in RT-D3 compared to those in RT-D1, while the expression levels of CT-D3 were found to be significantly higher than those in RT-D3. Expression levels of Bad protein in CT-D3 were significantly lower than those in RT-D3. A comparative analysis of RT-D3 and CT-D3 demonstrated that both the ratios of Bad/14–3–3ζ and GPIbα/14–3–3ζ increased significantly following cold storage. The ratio was significantly larger following a 3-day cold storage in comparison to that at RT. During cold storage of platelets, the enhanced association between 14–3–3ζ and GPIbα was demonstrated to improve exposure of phosphatidylserine, and the enhanced association between 14–3–3ζ and Bad was shown to delay the depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential.

Keywords: 14–3–3ζ, GPIbα, Bad, Cold storage, Platelets

Background

Currently, there is an increasing interest in the possibility of storing platelet concentrates below standard temperatures [1]. It is possible that cold platelets could be more effective in bleeding patients and possess a lower risk of bacterial transmission. In vitro studies have demonstrated that platelets stored at cold temperature (CT, 2–6 °C) are functionally and metabolically superior in comparison to platelets stored at room temperature (RT). Recently, Bynum et al. [2] demonstrated that a 4 °C storage temperature functioned to extend platelet mitochondrial function and viability.

The seven members of the mammalian 14–3–3 protein family are molecular adaptors and demonstrated the involvement in many cellular functions, including positive and negative roles in programmed cell death through their effects on protein stability and protein localization. It has also been recently reported that 14–3–3ζ functions to regulate the mitochondrial respiratory reserve that is associated with platelet phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure and procoagulant function [3]. Studies have demonstrated the involvement of 14–3–3 proteins in numerous cellular functions, including their positive and negative roles in apoptosis via their effects on protein stability and protein localization [4]. Platelets express numerous 14–3–3 isoforms, including 14–3–3ζ, which has previously been implicated in the regulation of GPIba function for platelet activation and signaling. However, the role of the GPIba-14–3–3ζ interaction in the regulation of platelet function is complicated, and these results are inconsistent [5, 6]. Our deep sequencing data analysis has demonstrated that 14–3–3ζ, GPIba, and Bad exhibited differential expression levels in cold stored platelets in comparison to platelets stored at RT (data not published).

In the current study, we have investigated the role of 14–3–3ζ in the regulation of platelet apoptosis by studying interactions of GPIba-14–3–3ζ and Bad-14–3–3ζ. Our study demonstrated an enhanced GPIba-14–3–3ζ interaction correlated with the exposure of PS, and an enhanced Bad-14–3–3ζ interaction correlated with maintenance of the mitochondrial membrane potential. The purpose of the present study was to carefully characterize the function of 14–3–3ζ protein as the pro-survival signaling hubs.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The primary antibodies used to detect Bcl-xL, Bak, and 14–3–3ζ were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA), GPIbα antibody was purchased from Emfret Analytics (Eibelstadt, Germany), and Bad, Phospho-Bad (Ser155), cytochrome c, caspase 3, caspase 9, and β-actin antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

In this study, the apoptosis and the expression of 14–3–3ζ and Bcl-2 family proteins under different platelet preservation conditions were analyzed. The interaction between 14–3–3ζ and Bcl-2 family proteins was further studied. The role of 14–3–3ζ protein during platelet storage was analyzed by flow cytometry and Western blot.

Apheresis Platelet Samples

Apheresis platelets were collected from seven healthy blood donors from the Shanghai Blood Center, China. Donors provided written informed consent in accordance with institutional ethics guidelines. Single-apheresis units (n = 7) were collected and stored for 3 days at RT (20–24 °C) with gentle agitation. Two aliquots of 10 mL apheresis platelets were drawn from every unit and were then transferred into 15 ml minibags for a 3-day storage period at a CT (2–6 °C) without agitation. One minibag was used for each time point (Day 1, D1 or Day 3, D3) and each storage temperature condition (20–24 °C or 2–6 °C).

Flow Cytometric Analysis

To determine the mitochondrial membrane potential, the washed platelet suspension (3 × 108/ml) was incubated with JC-1 (0.5 mM, 15 min, 37 °C) and 10,000 platelets were analyzed using flow cytometry on a FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Washed platelets were mixed with Annexin V–binding buffer and Annexin V–FITC at a 10:50:1 ratio. Samples were gently mixed and incubated at RT for 15 min in the dark. Samples were then analyzed using flow cytometry.

Western Blot Analysis

For protein expression analysis, washed platelet suspensions (1 × 109/ml) were lysed in 200 μl chilled lysis buffer (0.5% Triton-X 100, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) for 30 min on ice, followed by centrifugation at 13,400 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Lysates were then separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and electroblotted onto a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagent, and the integrated density values were calculated using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). All protein levels were normalized to β-actin expression.

To determine the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c, washed platelets (1 × 108/ml) were resuspended in 30 μl of mitochondrial isolation buffer (20 mM HEPES, 250 mM sucrose, 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4) containing 0.05% digitonin on ice for 30 min. Samples were then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 3 min and the supernatants were analyzed by western blot using a cytochrome c antibody.

Coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP)

Washed platelets (1 × 109/ml) were lysed in 500 μl chilled lysis buffer (1% 3 (3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio-1-propane sulfonate, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0) with a protease inhibitor cocktail on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 13,400 × g for 15 min at 4 °C in order to remove unlysed cells. Different antibodies were cross-linked to Protein A Dynabeads using 20 mM dimethylpimelimidate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and the cross-linked antibodies were incubated with platelet lysates overnight on a rocker at 4 °C. Samples were then centrifuged at 5000 × g for 30 s at 4 °C to pellet the beads. Beads were then washed 3 times with lysis buffer prior to elution in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading dye and analysis by immunoblotting. Quantification was carried out using Quantity One software.

Statistical Analysis

Results from independent experiments are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism 6 software and significant differences were determined using the Student’s t test. P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Flow Cytometric Analysis for Apoptosis of Storage Platelets

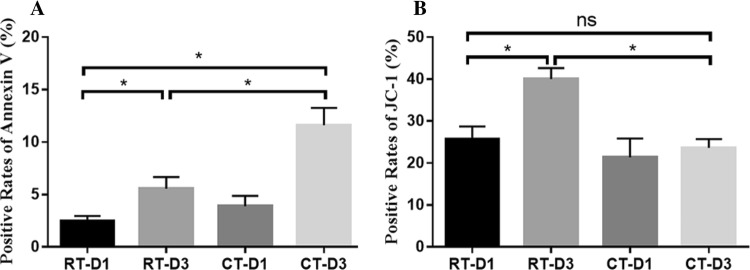

Under the RT storage conditions, both Annexin V and JC-1 exhibited significant increases in Day 3 compared to Day 1 samples (Fig. 1). In comparison to RT storage, 3 Day cold storage samples exhibited increased positive rates of Annexin V and decreased positive rates of JC-1.

Fig. 1.

Storage induced apoptosis events. The PS exposure (Annexin V) (a) and mitochondrial membrane potential (JC-1) (b) were determined using flow cytometry. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 7). *P < 0.05, nsP > 0.05, student’s t test

The Activation Analysis of Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathway

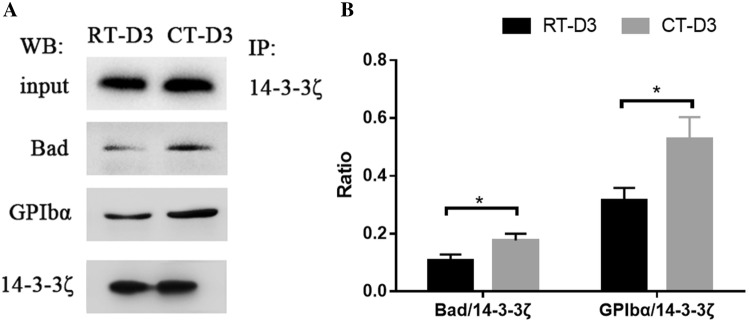

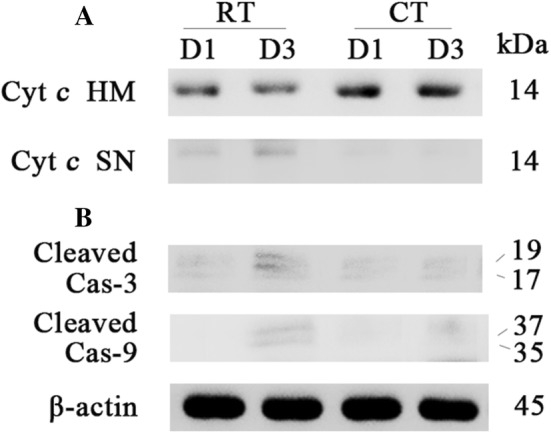

In order to explore activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, we analyzed cytochrome c release and caspase cleavage following a 3-day storage period under either RT or CT conditions. As Fig. 2 showed that the release of cytochrome c and caspase-3 and 9 cleavage was observed only in platelets stored under 3-day RT conditions.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of the activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. a Release of mitochondrial cytochrome c was assessed by western blot analysis for cytochrome c content in the heavy membrane (HM) fraction containing mitochondria and the supernatant (SN) fraction containing the cytosol. b Cleavage of caspase-3 and 9 was analyzed by western blot with β-actin as a loading control

The Comparison of Bcl-xL and Bak Expression

The expression levels of Bcl-xL and Bak during the 3-day storage conditions were analyzed at either RT or CT. It was demonstrated in Fig. 3 that the anti-apoptosis protein Bcl-xL was downregulated and the pro-apoptosis protein Bak was upregulated under RT storage conditions. Both Bcl-xL and Bak of CT-D3 exhibited no significant changes in comparison to either RT-D1 or CT-D1.

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis of Bcl-xL and Bak in RT or CT storage platelets. Western blot analysis (a), densitometry of immunoblots for Bcl-xL (b) and Bak (c). *P < 0.05, nsP > 0.05, student’s t test

The Expression of 14–3–3ζ and 14–3–3ζ-Binding Proteins

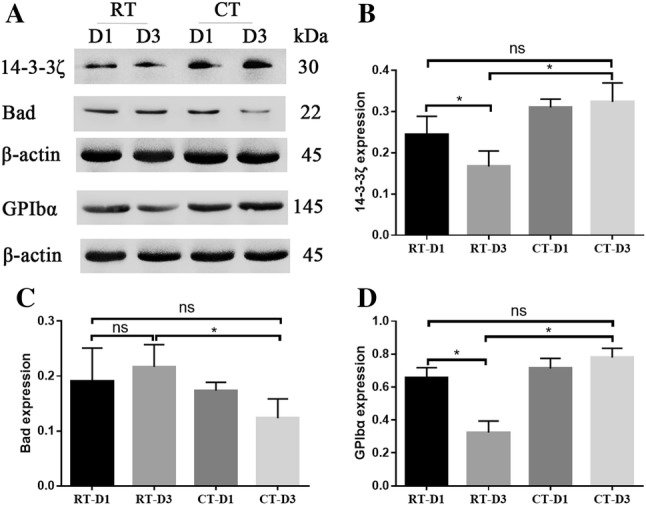

Analysis of 14–3–3ζ, Bad and GPIbα protein expression levels were determined by Western blot (Fig. 4a). In comparison, it was observed that expression levels of 14–3–3ζ and GPIbα significantly decreased in RT-D3 in comparison to those in RT-D1, while CT-D3 expression levels were significantly increased compared to those in RT-D3. We observed no significant difference between CT-D3 and RT-D1. Bad protein expression levels in CT-D3 were found to be significantly lower in comparison to those in RT-D3, with no significant difference between CT-D3 and RT-D1, and RT-D1 and RT-D3.

Fig. 4.

Western blot analysis of 14-3-3ζ, Bad and GPIbα in RT or CT storage platelets. Western blot analysis (a), densitometry of immunoblots for 14–3–3ζ (b), Bad (c) and GPIbα (d). *P < 0.05, nsP > 0.05, student’s t test

The Association of 14–3–3ζ with GPIbα and Bad

In order to further analyze protein functions, the interactions of 14–3–3ζ with GPIbα and Bad were detected using co-IP. Bad and GPIbα proteins were precipitated by 14–3–3ζ protein, and the results showed that there was an interaction between 14–3–3ζ and Bad or GPIbα (Fig. 5). A comparative analysis of RT-D3 and CT-D3 demonstrated that both the ratios of Bad/14–3–3ζ and GPIbα/14–3–3ζ were increased significantly following cold storage.

Fig. 5.

14–3–3ζ interactions with Bad and GPIbα determined using coimmunoprecipitation. Coimmunoprecipitation analysis (a), densitometry of immunoblots for 14–3–3ζ interaction with Bad and GPIbα (b). *P < 0.05, student’s t test

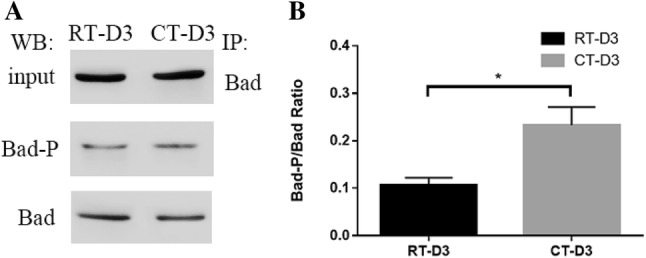

Analysis of Dephosphorylation of Bad

Upon confirming the interaction of Bad and 14–3–3ζ, we analyzed the Bad phosphorylation using co-IP, measuring the Bad-P/Bad ratio. As shown in Fig. 6, the ratio was significantly larger following 3 days cold storage in comparison to RT storage.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of Ser-phosphorylated Bad using coimmunoprecipitation. Coimmunoprecipitation analysis (a), densitometry of immunoblots for the ratio of Bad-p/Bad (b). *P < 0.05, student’s t test

Discussion

Refrigerated platelets may possess benefits, including a lowered risk of bacterial contamination, and improved haemostatic competence in vivo and in vitro, both of which could function to facilitate an extended platelet shelf life. How could cold storage function to extend platelet life span without lowering functionality? In this study, we describe the role of 14–3–3ζ in the regulation of intrinsic apoptosis during platelet cold storage.

Considering that apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction occur as early as on day 2–3 during storage [7, 8], we chose to examine 3-day storage platelets in this study. An increase in both activation and apoptosis markers has been demonstrated to occur during RT storage. In contrast, the effects of refrigeration on platelet receptor expression remain contentious. In this study, JC-1 and Annexin V results were found to be inconsistent during cold storage. Though JC-1 and Annexin V are both indicators for the early detection of cell apoptosis, their meanings are different. Specifically, JC-1 indicates depolarisation of the mitochondrial inner transmembrane potential, while Annexin V indicates the exposure of PS on the platelet surface. Our results suggested that platelets in cold storage only drove the surface exposure of PS, while the mitochondrial inner transmembrane potential was stabilized. These results are consistent with those results that have demonstrated that cold storage leads to the preservation of the mitochondrial potential and function in comparison to RT storage [2].

In order to further analyze platelet apoptosis during cold storage, we analyzed activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway and expression levels of bcl-2 family proteins. The Bcl-2 family proteins could function to determine platelet lifespan by the regulation of the mitochondrial outer membrane integrity. Following 3 days of cold storage, platelets were found to exhibit no signs of cytochrome c release, or activation of caspase enzymes, while activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway was observed to be triggered at 3-day RT storage. Cold storage platelets were found to maintain Bcl-xL and Bak expression, and it was suggested that this maintained interaction could restrain apoptosis. Evidence for the interaction of Bak and Bcl-xL in platelets supports the idea that Bcl-xL can function to ensure platelet survival by sequestering Bak [8, 9]. During cold storage, platelets could delay the occurrence of mitochondria-mediated intrinsic apoptosis.

In nucleated cells, 14–3–3ζ functions as an upstream regulator of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, where it functions to sequester cytosolic Bad, thereby protecting its phosphorylated, dormant state against activation [10]. In anuclear platelet cells, studies have demonstrated that 14–3–3ζ could regulate PS exposure and mitochondrial function [3]. In this study, we demonstrated enhanced associations of 14–3–3ζ with both GPIbα and Bad. These results suggest that the association of 14–3–3ζ with GPIbα could function to induce platelet PS exposure. It has also been demonstrated that Bad associated with 14–3–3ζ is phosphorylated at Ser155 [11]. Our results demonstrated an enhanced association of 14–3–3ζ with Bad, which could play a role in the maintenance of the mitochondrial potential. This is supported by a recent study which demonstrated that cold storage could protect the mitochondrial integrity and extend mitochondrial function [2]. In this study, we hypothesized that cold storage damaged the surface markers, while protecting mitochondrial integrity.

Previous studies on beta cells have demonstrated that cytokines function to induce the dephosphorylation of Bad, followed by a cytoplasm-to-mitochondrial translocation of Bad for the initiation of apoptosis [12]. In fact, the dissociation of 14–3–3ζ-phosphoBad could lead to the dephosphorylation of phospho-Bad and Bad activation, which would provide a further signal to pro-apoptotic Bak, resulting in a fall in the mitochondrial membrane potential. In comparison to RT storage, platelets stored at CT exhibited an increased proportion of phospho-Bad in this study. This implied that cold storage could slow the BH3-only proteins induced platelet apoptosis.

Increased global interest has arisen in the cold storage of platelets as an alternative to RT storage. Considering cold induced platelet apoptosis, gaining a better understanding of the mechanism behind this would help to improve the knowledge and pave the way for the clinical practice of certain indications in platelet transfusion. Our study characterized storage induced apoptosis in platelets via the regulation of 14–3–3ζ. Further experimental work is required to fully elucidate the mechanism in our future study.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by the Academic Leaders Training Program of Pudong Health Bureau of Shanghai (Grant No. PWRd2019-03), the Shanghai Key Medical Speciality Construction Plan (Grant No. ZK2019B25), The Outstanding Clinical Discipline Project of Shanghai Pudong (Grant No. PWYgy2018-03). The finders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethics Approval

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai University of Medicine and Health Sciences Affiliated Zhoupu Hospital.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Berzuini A, Spreafico M, Prati D. One size doesn’t fit all: should we reconsider the introduction of cold-stored platelets in blood bank inventories? F1000Research. 2017;6:95. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.10363.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bynum JA, Meledeo MA, Getz TM, Rodriguez AC, Aden JK, Cap AP, et al. Bioenergetic profiling of platelet mitochondria during storage: 4 degrees C storage extends platelet mitochondrial function and viability. Transfusion. 2016;56(Suppl 1):S76–84. doi: 10.1111/trf.13337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoenwaelder SM, Darbousset R, Cranmer SL, Ramshaw HS, Orive SL, Sturgeon S, et al. 14–3–3zeta regulates the mitochondrial respiratory reserve linked to platelet phosphatidylserine exposure and procoagulant function. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12862. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison DK. The 14–3–3 proteins: integrators of diverse signaling cues that impact cell fate and cancer development. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19(1):16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu M, Xi X, Englund GD, Berndt MC, Du X. Analysis of the roles of 14–3–3 in the platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX-mediated activation of integrin alpha(IIb)beta(3) using a reconstituted mammalian cell expression model. J Cell Biol. 1999;147(5):1085–1096. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bialkowska K, Zaffran Y, Meyer SC, Fox JE. 14–3–3 zeta mediates integrin-induced activation of Cdc42 and Rac. Platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX regulates integrin-induced signaling by sequestering 14–3–3 zeta. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(35):33342–33350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perales Villarroel JP, Figueredo R, Guan Y, Tomaiuolo M, Karamercan MA, Welsh J, et al. Increased platelet storage time is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired platelet function. J Surg Res. 2013;184(1):422–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.05.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan Y, Xie R, Zhang Q, Zhu X, Han J, Xia R. Bcl-xL/Bak interaction and regulation by miRNA let-7b in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway of stored platelets. Platelets. 2019;30(1):1–6. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2017.1371289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogler M, Hamali HA, Sun XM, Bampton ET, Dinsdale D, Snowden RT, et al. BCL2/BCL-X(L) inhibition induces apoptosis, disrupts cellular calcium homeostasis, and prevents platelet activation. Blood. 2011;117(26):7145–7154. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Wal DE, Du VX, Lo KS, Rasmussen JT, Verhoef S, Akkerman JW. Platelet apoptosis by cold-induced glycoprotein Ibalpha clustering. J Thrombosis Haemost JTH. 2010;8(11):2554–2562. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao L, Liu J, He C, Yan R, Zhou K, Cui Q, et al. Protein kinase A determines platelet life span and survival by regulating apoptosis. J Clin Investig. 2017;127(12):4338–4351. doi: 10.1172/JCI95109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grunnet LG, Aikin R, Tonnesen MF, Paraskevas S, Blaabjerg L, Storling J, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines activate the intrinsic apoptotic pathway in beta-cells. Diabetes. 2009;58(8):1807–1815. doi: 10.2337/db08-0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]