Abstract

Background

CTCF encodes 11-zinc finger protein which is implicated in multiple tumors including the carcinoma of the breast. The Present study investigates the association of CTCF mutations and their expression in breast cancer cases.

Methods

A total of 155 breast cancer and an equal number of adjacent normal tissue samples from 155 breast cancer patients were examined for CTCF mutation(s) by PCR-SSCP and automated DNA sequencing. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) method was used to analyze CTCF expression. Molecular findings were statistically analyzed with various clinicopathological features to identify associations of clinical relevance.

Results

Of the total, 16.1% (25/155) cases exhibited mutation in the CTCF gene. Missense mutations Gln > His (G > T) in exon 1 and silent mutations Ser > Ser (C > T) in exon 4 of CTCF gene were analyzed. A significant association was observed between CTCF mutations and some clinicopathological parameters namely menopausal status (p = 0.02) tumor stage (p = 0.03) nodal status (p = 0.03) and ER expression (p = 0.04). Protein expression analysis showed 42.58% samples having low or no expression (+), 38.0% with moderate (++) expression and 19.35% having high (+++) expression for CTCF. A significant association was found between CTCF protein expression and clinicopathological parameters include histological grade (p = 0.04), tumor stage (p = 0.04), nodal status (p = 0.03) and ER status (p = 0.04).

Conclusions

The data suggest that CTCF mutations leading to its inactivation significantly contribute to the progression of breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, CTCF, Immunohistochemistry, Mutation, PCR-SSCP

1. Introduction

Breast cancer, that represents nearly 1/4th of total cancers diagnosed in female (Ferlay et al., 2015), results from the interaction between multiple genes and environmental factors (Kaaks et al., 2005) (Xie et al., 2006).

CTCF (CCCTC-binding factor) regulates gene expression through activation/repression of the promoter, chromatin lining and imprinting of genomes (Ong and Corces, 2014), along with involvement in the establishment of the 3D structure of the genome and genomic segments (Holwerda and de Laat, 2013). It also has a tumor suppressor function and is commonly deleted or mutated in breast cancer cell lines and breast tumors (Ji et al., 2016, Kaiser et al., 2016, Sabarinathan et al., 2016, Umer et al., 2016).

11-zinc fingers enable the protein to bind diverse gene sequences making it a universal transcription factor (Kim et al., 2007, Nakahashi et al., 2013). CTCF is a tumor suppressor suspects linked with familial breast cancer (Ohlsson et al., 2001). Genomic platforms and integration of sequence data suggest that CTCF may harbor driver mutation in breast cancer (Cancer Genome Alas, 2012, Nik-Zainal et al., 2016). CTCF protein levels are elevated in many breast tumors as well as cancer cell lines (Docquier et al., 2005). The epigenetic control of the BAX gene by CTCF helps the cancer cells to evade apoptosis in addition to influencing genome imprinting, intronic transcription, inactivation of X-chromosome, and post-transcription processing (Docquier et al., 2005, Mendez-Catala et al., 2013). It further downregulates the transcription of the c-Myc oncogene and impacts the expression of maternal H19 allele (Holmgren et al., 2001), as well as establishes chromatin boundaries and mediating long-range chromatin interactions (Phillips and Corces, 2009).

16q22-24 region, the location of CTCF, commonly exhibits loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in breast cancer (Lindblom et al., 1993, Cleton-Jansen et al., 1994). Interestingly, this phenomenon is associated with longer survival and delayed metastasis (Lindblom et al., 1993, Hansen et al., 1998).

CTCF can be deregulated in multiple ways, including germline and somatic (missense and nonsense) mutations resulting in the onset and progression of genetic disorders like human cancers (Lupianez et al., 2015, Filippova et al., 1998, Rubio-Perez et al., 2015). The CTCF gene mutation(s) leading to many human cancers strongly suggest the critical loss of function as important as tumor suppression (Marshall et al., 2017, Ohlsson et al., 2001, Filippova et al., 1998).

An early in vitro report indicated the anti-proliferative activity of CTCF by showing that it repressed the cell proliferation (Lutz et al., 2000). However, the precise role of CTCF in the onset or progression of cancer remains to be elucidated. The efforts have been made in many human tumors, but breast cancer is scarcely studied (Takai et al., 2001, Filippova et al., 2002, Yeh et al., 2002, Aulmann et al., 2003, Ulaner et al., 2003).

The current study aimed to find mutations in various hot spot exons of CTCF by polymerase chain reaction-single stranded conformation polymorphism (PCR-SSCP) followed by sequencing of DNA isolated from cancerous and adjacent normal breast tissues to identify mutational hot spots of CTCF contributing to carcinogenesis. Additionally, the expression of CTCF protein was also analyzed to show the relationship between CTCF mutation and its expression with various clinico-pathological parameters.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological samples

The subjects were informed, and consent forms were collected from all the participants after the ethical clearance from the institutional ethics committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, India. 155 female breast cancer tissue samples and an equal number of adjacent normal tissues (measuring 5–10 mm), were obtained and stored in PBS and formalin between 2010 and 2014 from the Department of Surgical Oncology, AIIMS, New Delhi India. Breast cancer stages were determined using the TNM staging system or American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). The clinicopathological variables are age, histological type, tumor size, histological grade, menopausal status, tumor stage, nodal status, ER expression, PR expression and Her2/Neu.

2.2. DNA isolation

DNA was isolated from the cases and healthy control tissue by using the standard phenol/chloroform method as described previously (Sambrook et al., 1989). DNA concentration and purity were determined using electrophoresis and UV spectrophotometry before storing it in TE buffer.

2.3. PCR-SSCP analysis

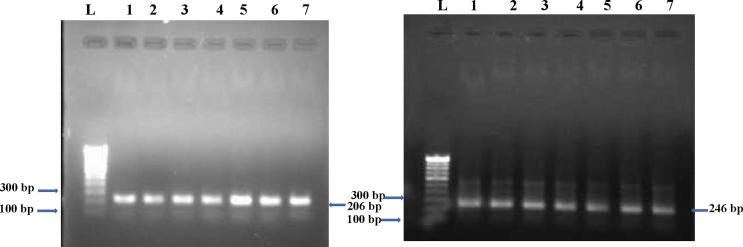

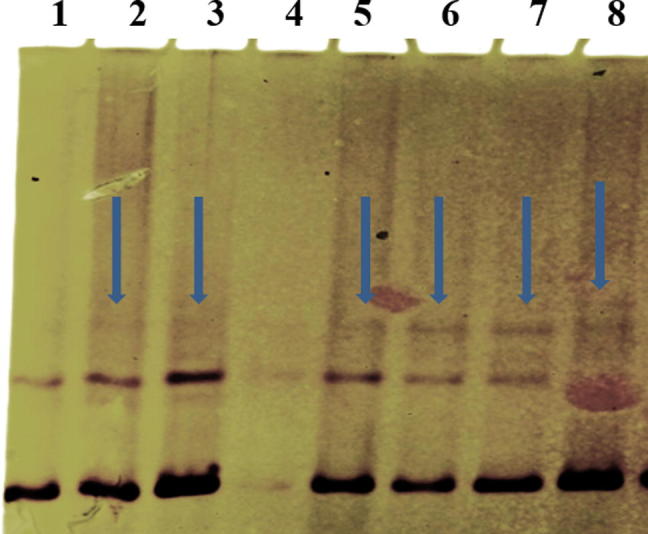

Hot spot exon 1 and 4 of CTCF gene were probed for the presence of mutation using the tumor and normal control DNA with the primers (table 1). PCR product showed the presence of 206 bp and 246 bp amplicons (Fig. 1) as identifed by using Quantity One Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA). The purified product was assayed for any alteration in the electrophoretic mobility as described previously (Orita et al., 1989). Comparison of single-stranded DNA bands of the tumor and normal control to the identification of SSCP positive samples (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primer sequences used for amplification of different exons.

| Gene | Consensus sequence | Annealing temperature (oc) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTCF Exon 1 FP | 5′- GGTGATGATGGAACAGCTGG -3′ | 60 | 206 |

| CTCF Exon 1 RP | 5′- TGGTAGCAACAGGTACAGTC -3′ | ||

| CTCF Exon 4 FP | 5′-TCACATTCGCTCTCATACTGG-3′ | 58 | 246 |

| CTCF Exon 4 FP | 5′-CGGAGAAGCATTATCAATTC-3′ |

Fig. 1.

Amplified exon products (206 and 246 bp) of CTCF gene. Lane L: Molecular marker of 100 bp, Lanes 1–7: Amplicons from the Breast cancer tissues samples.

Fig. 2.

SSCP (non-radio active) analysis of CTCF gene shows a variation/ shift in band pattern lane 2, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 8 of the breast tumor samples when compared with normal sample in lane 1.

2.4. DNA sequencing

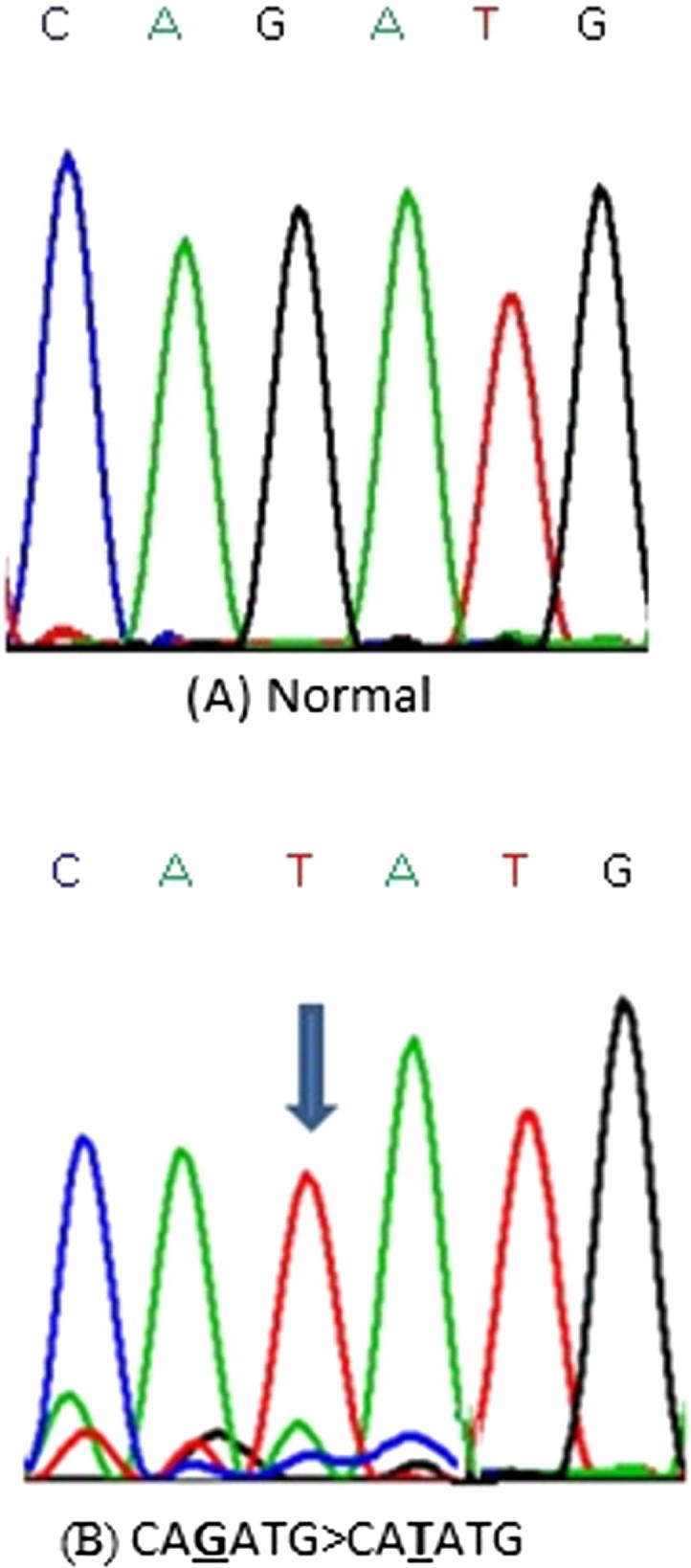

The SSCP positive samples were re-amplified and purified before sequencing twice to prevent the formation of any artifacts (ABI PRISM310 dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready reaction Kit) and analyzed using Sequencing Analysis Software 3.4.1 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Representative partial electropherograms of Mutant (B) (shown by arrow) with Normal (A) adjacent forms of CTCF gene showing substitutin G>T.

2.5. IHC analysis

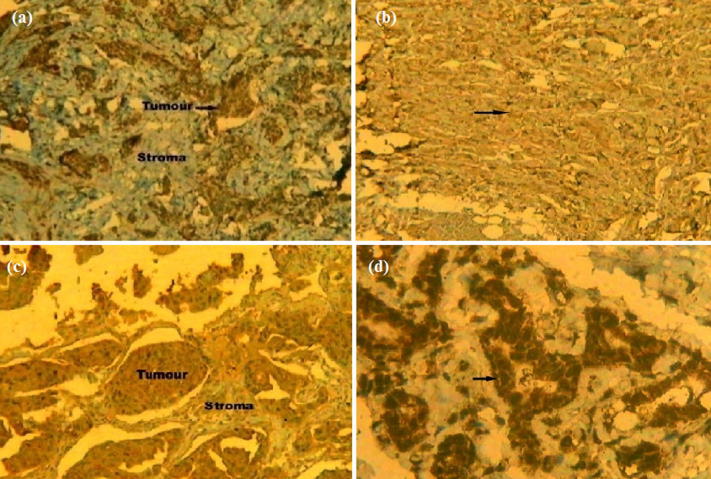

Immunohistochemical staining was done to assess CTCF protein expression using the anti-human CTCF antibody (GeneScript, USA, Catalog # A01529) (Barbareschi et al., 1996). Briefly, breast cancer tissue samples cut into 2 to 4 μm section embedded in poly-L- lysine coated slides were treated with xylene, alcohol, and heat to retrieve the antigen. The slides were finally incubated with anti-CTCF antibody and developed using straptavidin Horse-reddish peroxidase detection kit (GeneScript USA). Slides scoring as Low or no expression (+), Moderate (++) and High expression (+++) representation of number and distribution of cells among cases and controls was done using Olympus BX 50, Tokyo.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Chi-square test (χ2) was used to assess the association of CTCF mutation and its expression with various clinicopathological parameters using GraphPad Prism 6.0. The P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Mutation(s) in CTCF and clinicopathological parameters

A total of 25 (16.12%) breast cancer cases showed mutations in the exon 1 and exon 4 including a missense mutation (Gln > His, G > T) in seventeen cases and silent mutation (Ser > Ser, C > T) in eight cases (Table 2) (Fig. 6).

Table 2.

Details of CTCF gene Mutation(s) in Female Breast Cancer Cases from India.

| Affected Codon | Base Position | Base Change | Amino Acid Change | Mutation Effect | No. of Patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72 | 216 | CAG > CAT (G > T) | Glutamine > Histidine (Gln > His) | Missense | 17 |

| 388 | 1455 | TCC > TCT (C > T) | Serine > Serine (Ser > Ser) | Silent | 08 |

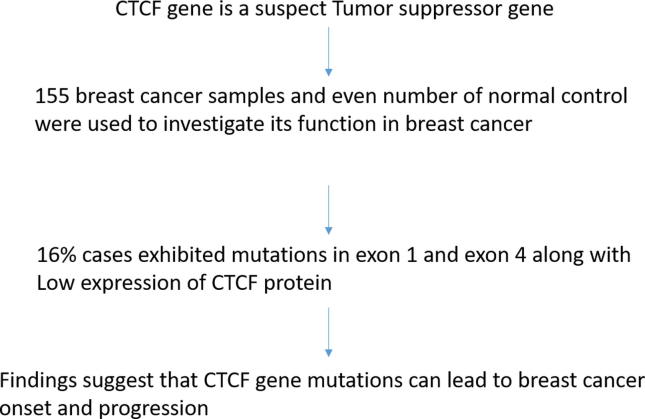

Fig. 6.

Graphical abstract.

No mutation was observed in normal control samples. The relationship between CTCF mutations and clinicopathological parameters showed a significant correlation with patients menopausal status (p = 0.02), tumor stage (p = 0.03), nodal status (p = 0.03) and estrogen receptor (ER) expression (p = 0.04 (Table 3). However, the association with age, histological type, tumor size, histological grade, progesterone receptor (PR) expression, and Her2/Neu failed to reach statistical significance.

Table 3.

Correlation between mutations of human CTCF gene with clinicopathological parameters.

|

Number of patients |

155 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | No. of cases (n = 155) | Mutations | Mutation rate (%) | χ2 value | P value |

| Age | |||||

| >50 | 80 | 16 | 20.00 | 1.831 | 0.176 |

| ≤50 | 75 | 09 | 12.00 | ||

| Menopausal status | |||||

| Pre | 70 | 06 | 8.57 | 5.390 | 0.020** |

| Post | 85 | 19 | 22.35 | ||

| Histological Type | |||||

| Invasive ductal Carcinoma | 150 | 25 | 16.67 | 0.993 | 0.318 |

| (IDC) | |||||

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 00 | 0.00 | 05 | ||

| (ILC) | |||||

| Tumor Size | |||||

| ≤2cm | 65 | 07 | 10.77 | 2.377 | 0.123 |

| ˃2cm | 90 | 18 | 20.00 | ||

| Histological Grade | |||||

| Poorly differentiated (PD) | 40 | 05 | 12.50 | 1.596 | 0.450 |

| Moderately differentiated (MD) | 69 | 14 | 20.29 | ||

| Well differentiated (WD) | 46 | 06 | 13.04 | ||

| Tumor Stage | |||||

| Stage II (a+b) | 73 | 07 | 09.59 | 4.363 | 0.036** |

| Stage III (a+b) + IV | 82 | 18 | 21.95 | ||

| Nodal Status | |||||

| Positive | 81 | 18 | 22.22 | 4.656 | 0.030** |

| Negative | 74 | 07 | 09.46 | ||

| Estrogen Receptor (ER) Expression | |||||

| Positive | 72 | 07 | 09.72 | 4.080 | 0.043** |

| Negative | 83 | 18 | 21.68 | ||

| Progesterone Receptor (PR) Status | |||||

| Positive | 66 | 08 | 12.12 | 1.365 | 0.242 |

| Negative | 89 | 17 | 19.10 | ||

| Her2/Neu | |||||

| Positive | 69 | 07 | 10.14 | 3.292 | 0.069 |

| Negative | 86 | 18 | 20.93 |

P-value < 0.05** was considered significant.

3.2. CTCF expression and clinicopathological features

Of all 155 cases, 66 (42.59%) showed low/ no expression (+), 59 cases (38.06%) with moderate (++) expression and 30 cases (19.35%) had high (+++) expression for CTCF nuclear staining (Table 4, Fig. 5). A significant correlation was detected between CTCF protein expression and histological grade (p = 0.04), nodal status (p = 0.03), tumor stage (p = 0.04), and ER status (p = 0.04) (Table 5). However, the association with age (p = 0.29), menopausal status (p = 0.84), histological type (p = 0.56), tumor size (p = 0.464), PR status (p = 0.10) and Her2/Neu (p = 0.49) failed to reach significance (Table 5).

Table 4.

Profile of CTCF protein expression.

| CTCF gene expression | ||

|---|---|---|

| Low | 66/155 | 42. 59% |

| Moderate | 59/155 | 38. 06% |

| High | 30/155 | 19. 35% |

Fig. 5.

Representative Immunohistochemical slides (seen at 10X) showing (a) Low expression (+), (b) Moderate expression (++), (c) High expression (+++) of CTCF protein in Indian female breast cancer cases and (d) CTCF protein expression in normal control.

Table 5.

Correlation between the expression of CTCF protein and Clinico-pathological parameters of breast carcinoma.

| Parameters | n=155 | Low | Normal | High | χ2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| ˃50 | 80 | 35 | 14 | 31 | 2.447 | 0.294 |

| ≤50 | 75 | 29 | 21 | 25 | ||

| Menopausal status | ||||||

| Pre | 70 | 32 | 14 | 24 | 0.328 | 0.848 |

| Post | 85 | 35 | 18 | 32 | ||

| Histological Type | ||||||

| Invasive Ductal Carcinoma (IDC) | 150 | 60 | 39 | 51 | 1.158 | 0.560 |

| Invasive Lobular Carcinoma (ILC) | 05 | 02 | 02 | 01 | ||

| Tumour Size | ||||||

| ≤2cm | 65 | 23 | 18 | 24 | 1.532 | 0.464 |

| ˃2cm | 90 | 40 | 24 | 26 | ||

| Histological Grade | ||||||

| First | 40 | 20 | 09 | 11 | 09.791 | 0.044** |

| Second | 69 | 23 | 25 | 21 | ||

| hird | 46 | 12 | 11 | 23 | ||

| Tumor stage | ||||||

| Stage2 (a+b) | 73 | 23 | 18 | 32 | 6.079 | 0.047** |

| Stage3 (a+b) +4 | 82 | 38 | 23 | 21 | ||

| Nodal status | ||||||

| Positive | 81 | 38 | 21 | 22 | 6.824 | 0.033** |

| Negative | 74 | 24 | 15 | 35 | ||

| ER status | ||||||

| Positive | 72 | 22 | 17 | 33 | 6.008 | 0.049** |

| Negative | 83 | 40 | 19 | 24 | ||

| PR Status | ||||||

| Positive (+ve) | 66 | 36 | 12 | 18 | 4.475 | 0.106 |

| Negative (−ve) | 89 | 34 | 26 | 29 | ||

| Her2/Neu | ||||||

| Positive (+ve) | 69 | 24 | 19 | 26 | 1.413 | 0.493 |

| Negative (−ve) | 86 | 38 | 20 | 28 |

3.3. Correlation between mutation(s) and expression of CTCF cases

The mutation(s) found in the breast cancer patients was analyzed along with CTCF expression to elucidate the potential role of CTCF in breast cancer. The relationship of CTCF mutation with its expression was observed significantly in the case of low level (+) protein expression (p = 0.03). However, the link in cases of moderate (++) (p = 0.11) and high level (+++) (p = 0.43) protein expression was found not significant (Table 6).

Table 6.

Correlation between mutations and protein expression of CTCF gene in breast cancer patients

| Level of expression | No. of cases (n = 155) | Mutations (25/155 = 16.12%) | χ2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 69/155 (44.52%) | 16/155 (10.32%) | 4.581 | 0.032** |

| Moderate | 59/155 (38.06%) | 06/155 (3.87%) | 2.501 | 0.113 |

| High | 27/155 (17.42%) | 03/155 (1.93%) | 0.608 | 0.435 |

4. Discussion

Aberrant CTCF is linked with several diseases/disorders, including cancer (Aulmann et al., 2003, Prawitt et al., 2005, Herold et al., 2012, Gregor et al., 2013, Bastaki et al., 2017). The tumor suppressor function of CTCF is speculated based upon its impact on critical genes like p53, Myc, BRCA1, p19/ARF involved in cancer onset and progression (Bell and Felsenfeld, 2000, Klenova et al., 2002, Qi et al., 2003, Ohlsson et al., 2001).

Recent studies suggest that overexpression of CTCF contributes to tumor development in breast cancer by downregulating HOXA10 and H3K27me3 expressions (Mustafa et al., 2015, Lee et al., 2017). Interestingly, the repression of CTCF leads to the overexpression of BAX and eventual apoptosis (Docquier et al., 2005).

Mutations have been detected in CTCF chromatin binding sites (CBS) in multiple cancers, especially mutations of A-T base pairs (Katainen et al., 2015). The loss of CTCF poly ADP-ribosyltion in breast cancer leading to the expression of both 180-kDa and 130-kDa in comparison to only 180-kDa CTCF in normal breast tissues likely contributes to the progression of breast cancer (Docquier et al., 2009).

Although CTCF-130-kDa or Rb2/p130 can be used as the biomarker for the cancer progression, the utility of CTCF-130-kDa as the disease prognosis biomarkers remain to be investigated (Long et al., 2018, Shi et al., 2018, Wang et al., 2017, Wu et al., 2018, Kawamura et al., 2018). Recent studies show that CTCF regulates changes of the 3D genome organization (Wang, 2018, Singh and Shrivastava, 2017, Liu and Wu, 2018) in the pathogenesis of disease (Szalaj and Plewczynski, 2018, Ma et al., 2018, Terabayashi and Hanada, 2018).

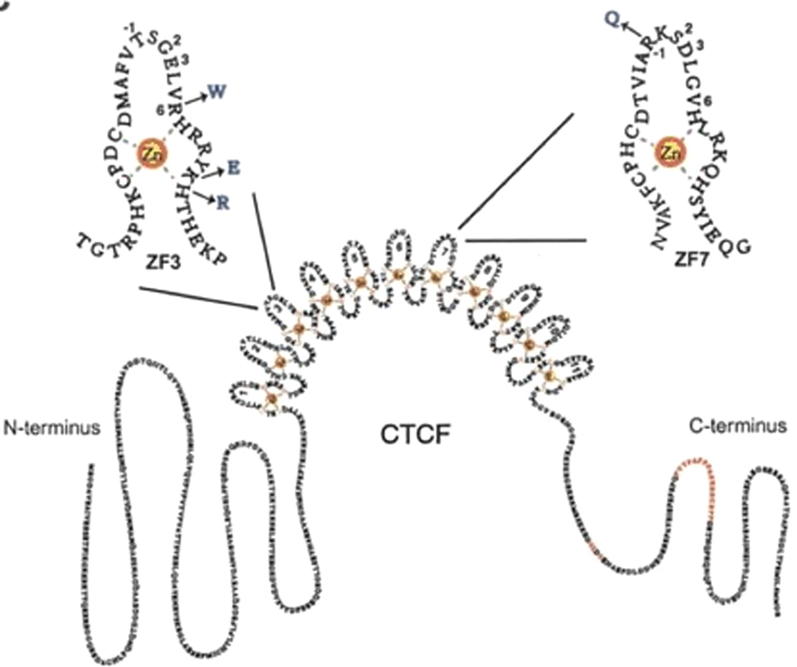

In the present study, we screened the hotspot coding regions of CTCF gene for the mutation(s) by PCR-SSCP in 155 cases of female breast carcinoma along with corresponding adjacent healthy control. We found 25 (16.1%) missense and silent mutations in female breast cancer tissues as shown in the table 2. The mutation(s) were identified at codon 72 leading to Gln > His (G > T), and at codon 1455 leading to Ser > Ser(C > T). The missense codon mutations in CTCF zinc finger domain 3, observed in the present study may impact the CTCF binding to the promoters of genes related to cellular proliferation like MYC, PLK, PIM-1, p19ARF, and Igf2/H19 (Fig. 4) (Filippova et al., 2002). The mutation(s) may also have resulted in repression of the wild-type allele and low/ no protein expression (Aulmann et al., 2003). Moreover, our data exhibited the altered expression profiles of CTCF which may be due to the result of potential mutation(s) in the CTCF exonic region and thus can contribute in the progression of breast cancer as shown in an early study (Tiffen et al., 2013).

Fig. 4.

Impact of mutation on CTCF protein.

Importantly, we observed that CTCF mutations were only found in breast cancer tissue and not in healthy tissues. The analysis of potential relationship with the patient’s ages, menopausal status, histological types, tumor sizes, histological grades, tumor stages, lymph node metastases, steroid receptors (ER & PR) and Her2/neu amplifications to elucidate the role of mutation(s) in CTCF gene in the progression of breast cancer revealed a significant relationship between CTCF mutations and patients’ menopausal status (p = 0.02), tumor stages (p = 0.03), lymph node metastases (p = 0.03) and ER (p = 0.04). The significant association with the clinical parameters further emphasizes the link between CTCF and breast cancer progression. No significant association was found with patient ages, histological types, tumor sizes, histological grades, PR and Her2/neu amplifications.

CTCF protein expression analysis was performed to explore the possible role of CTCF in female breast cancer cases and also to define the biomarker property.

An early study showed moderate to strong nuclear staining of CTCF protein (Aulmann et al., 2003). More than 80% of the cases included in our study showed a low or moderate CTCF expression which was significantly linked with histological grades (p = 0.04), tumor stages (p = 0.04), lymph node involvements (p = 0.03) and ER (p = 0.04). No significant association was observed with parameters such as age, menopausal status, histological types, tumor sizes, PR status and Her2/neu amplification of breast cancer progression (Table 5) suggesting the involvement of detected mutations in expression and altered formations of the protein contributing to the onset and progression of breast cancer which is in agreement with the findings of an early study (Tiffen et al., 2013).

A significant association found between CTCF mutation and protein expression in the low level (+) category of protein expression (p = 0.03), whereas no significant association with the moderate (++) and high level (+++) of protein expression suggest that the progression of breast cancer may be related to the lower level of CTCF protein expression indicating towards the anti-proliferative activity of CTCF, and a potent breast cancer susceptible genes. The altered expression profiles of CTCF showing mainly nuclear expression in the current study are in agreement with the earlier studies using immunofluorescence to without any cytoplasmic staining (Zhang et al., 2004). In the present study, we found an association between CTCF expression and histological grade in the high percentage of low-grade tumors having less proliferative activity showing positive nuclear expression, whereas high-grade tumors primarily showed low or no expression. Our results are concordant with early reports indicating the ability of CTCF to inhibit cell growth and proliferation (Rasko et al., 2001).

5. Conclusions

Our study showed mutations (missense Gln > His, G > T and silent Ser > Ser, C > T) of the CTCF gene in Indian female breast cancer cases. The detected mutations showed that 16 (64%) mutations had a statistically significant association with low or no expression for CTCF when analyzed with IHC data. The findings suggest that CTCF may be a tumor suppressor gene and its inactivation may play an essential role in the progression of breast carcinoma. However, further clinical studies with larger sample size are needed to elucidate the fundamental role of CTCF gene in the breast cancer onset and progression in Indian population.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Government of India, New Delhi India (grant number 3/2/2/61/2011/MCD-3), for providing the fund for this study. The authors would like to thank all the breast cancer patients who participated in the study, and without whom the study would not have been possible.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Aulmann S., Blaker H., Penzel R., Rieker R.J., Otto H.F., Sinn H.P. CTCF gene mutations in invasive ductal breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2003;80:347–352. doi: 10.1023/A:1024930404629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbareschi, M., Caffo, O., Veronese, S., Leek, R.D., Fina, P., Fox, S., Bonzanini, M., Girlando, S., Morelli, L., Eccher, C., Pezzella, F., Doglioni, C., Dalla Palma, P., Harris, A., 1996. Bcl-2 and p53 expression in node-negative breast carcinoma: a study with long-term follow-up. Hum. Pathol., 27, 1149–1155. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bastaki F., Nair P., Mohamed M., Malik E.M., Helmi M., Al-Ali M.T., Hamzeh A.R. Identification of a novel CTCF mutation responsible for syndromic intellectual disability - a case report. BMC Med. Genet. 2017;18:68. doi: 10.1186/s12881-017-0429-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell A.C., Felsenfeld G. Methylation of a CTCF-dependent boundary controls imprinted expression of the Igf2 gene. Nature. 2000;405:482–485. doi: 10.1038/35013100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CANCER GENOME ATLAS, N., 2012. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature, 490, 61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cleton-Jansen A.M., Moerland E.W., Kuipers-Dijkshoorn N.J., Callen D.F., Sutherland G.R., Hansen B., Devilee P., Cornelisse C.J. At least two different regions are involved in allelic imbalance on chromosome arm 16q in breast cancer. Genes Chromosom. Cancer. 1994;9:101–107. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870090205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docquier F., Farrar D., D'Arcy V., Chernukhin I., Robinson A.F., Loukinov D., Vatolin S., Pack S., Mackay A., Harris R.A., Dorricott H., O'Hare M.J., Lobanenkov V., Klenova E. Heightened expression of CTCF in breast cancer cells is associated with resistance to apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5112–5122. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docquier F., Kita G.X., Farrar D., Jat P., O'Hare M., Chernukhin I., Gretton S., Mandal A., Alldridge L., Klenova E. Decreased poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of CTCF, a transcription factor, is associated with breast cancer phenotype and cell proliferation. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:5762–5771. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Dikshit R., Eser S., Mathers C., Rebelo M., Parkin D.M., Forman D., Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippova G.N., Lindblom A., Meincke L.J., Klenova E.M., Neiman P.E., Collins S.J., Doggett N.A., Lobanenkov V.V. A widely expressed transcription factor with multiple DNA sequence specificity, CTCF, is localized at chromosome segment 16q22.1 within one of the smallest regions of overlap for common deletions in breast and prostate cancers. Genes Chromosom. Cancer. 1998;22:26–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippova, G.N., Qi, C.F., Ulmer, J.E., Moore, J.M., Ward, M.D., Hu, Y.J., Loukinov, D.I., Pugacheva, E.M., Klenova, E.M., Grundy, P.E., Feinberg, A.P., Cleton-Jansen, A.M., Moerland, E.W., Cornelisse, C.J., Suzuki, H., Komiya, A., Lindblom, A., Dorion-Bonnet, F., Neiman, P.E., Morse, H.C., 3RD, Collins, S.J., Lobanenkov, V.V., 2002. Tumor-associated zinc finger mutations in the CTCF transcription factor selectively alter tts DNA-binding specificity. Cancer Res., 62, 48–52. [PubMed]

- Gregor A., Oti M., Kouwenhoven E.N., Hoyer J., Sticht H., Ekici A.B., Kjaergaard S., Rauch A., Stunnenberg H.G., Uebe S., Vasileiou G., Reis A., Zhou H., Zweier C. De novo mutations in the genome organizer CTCF cause intellectual disability. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;93:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen L.L., Yilmaz M., Overgaard J., Andersen J., Kruse T.A. Allelic loss of 16q23.2-24.2 is an independent marker of good prognosis in primary breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2166–2169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold M., Bartkuhn M., Renkawitz R. CTCF: insights into insulator function during development. Development. 2012;139:1045–1057. doi: 10.1242/dev.065268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren C., Kanduri C., Dell G., Ward A., Mukhopadhya R., Kanduri M., Lobanenkov V., Ohlsson R. CpG methylation regulates the Igf2/H19 insulator. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:1128–1130. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holwerda S.J., de Laat W. CTCF: the protein, the binding partners, the binding sites and their chromatin loops. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2013;368:20120369. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X., Dadon D.B., Powell B.E., Fan Z.P., Borges-Rivera D., Shachar S., Weintraub A.S., Hnisz D., Pegoraro G., Lee T.I., Misteli T., Jaenisch R., Young R.A. 3D Chromosome Regulatory Landscape of Human Pluripotent Cells. Cell Stem. Cell. 2016;18:262–275. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaaks R., Rinaldi S., Key T.J., Berrino F., Peeters P.H., Biessy C., Dossus L., Lukanova A., Bingham S., Khaw K.T., Allen N.E., Bueno-De-mesquita H.B., van Gils C.H., Grobbee D., Boeing H., Lahmann P.H., Nagel G., Chang-Claude J., Clavel-Chapelon F., Fournier A., Thiebaut A., Gonzalez C.A., Quiros J.R., Tormo M.J., Ardanaz E., Amiano P., Krogh V., Palli D., Panico S., Tumino R., Vineis P., Trichopoulou A., Kalapothaki V., Trichopoulos D., Ferrari P., Norat T., Saracci R., Riboli E. Postmenopausal serum androgens, oestrogens and breast cancer risk: the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2005;12:1071–1082. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser V.B., Taylor M.S., Semple C.A. Mutational Biases Drive Elevated Rates of Substitution at Regulatory Sites across Cancer Types. PLoS Genet. 2016;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katainen R., Dave K., Pitkanen E., Palin K., Kivioja T., Valimaki N., Gylfe A.E., Ristolainen H., Hanninen U.A., Cajuso T., Kondelin J., Tanskanen T., Mecklin J.P., Jarvinen H., Renkonen-Sinisalo L., Lepisto A., Kaasinen E., Kilpivaara O., Tuupanen S., Enge M., Taipale J., Aaltonen L.A. CTCF/cohesin-binding sites are frequently mutated in cancer. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:818–821. doi: 10.1038/ng.3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura Y., Takouda J., Yoshimoto K., Nakashima K. New aspects of glioblastoma multiforme revealed by similarities between neural and glioblastoma stem cells. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2018;34:425–440. doi: 10.1007/s10565-017-9420-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.H., Abdullaev Z.K., Smith A.D., Ching K.A., Loukinov D.I., Green R.D., Zhang M.Q., Lobanenkov V.V., Ren B. Analysis of the vertebrate insulator protein CTCF-binding sites in the human genome. Cell. 2007;128:1231–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenova, E.M., Morse, H.C., 3RD, Ohlsson, R., Lobanenkov, V.V., 2002. The novel BORIS + CTCF gene family is uniquely involved in the epigenetics of normal biology and cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol., 12, 399–414. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee J.Y., Mustafa M., Kim C.Y., Kim M.H. Depletion of CTCF in Breast Cancer Cells Selectively Induces Cancer Cell Death via p53. J. Cancer. 2017;8:2124–2131. doi: 10.7150/jca.18818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom A., Rotstein S., Skoog L., Nordenskjold M., Larsson C. Deletions on chromosome 16 in primary familial breast carcinomas are associated with development of distant metastases. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3707–3711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Wu J. History, applications, and challenges of immune repertoire research. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2018;34:441–457. doi: 10.1007/s10565-018-9426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long D., Yu T., Chen X., Liao Y., Lin X. RNAi targeting STMN alleviates the resistance to taxol and collectively contributes to down regulate the malignancy of NSCLC cells in vitro and in vivo. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2018;34:7–21. doi: 10.1007/s10565-017-9398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupianez D.G., Kraft K., Heinrich V., Krawitz P., Brancati F., Klopocki E., Horn D., Kayserili H., Opitz J.M., Laxova R., Santos-Simarro F., Gilbert-Dussardier B., Wittler L., Borschiwer M., Haas S.A., Osterwalder M., Franke M., Timmermann B., Hecht J., Spielmann M., Visel A., Mundlos S. Disruptions of topological chromatin domains cause pathogenic rewiring of gene-enhancer interactions. Cell. 2015;161:1012–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz M., Burke L.J., Barreto G., Goeman F., Greb H., Arnold R., Schultheiss H., Brehm A., Kouzarides T., Lobanenkov V., Renkawitz R. Transcriptional repression by the insulator protein CTCF involves histone deacetylases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1707–1713. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.8.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma T., Chen L., Shi M., Niu J., Zhang X., Yang X., Zhanghao K., Wang M., Xi P., Jin D., Zhang M., Gao J. Developing novel methods to image and visualize 3D genomes. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2018;34:367–380. doi: 10.1007/s10565-018-9427-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall A.D., Bailey C.G., Champ K., Vellozzi M., O'Young P., Metierre C., Feng Y., Thoeng A., Richards A.M., Schmitz U., Biro M., Jayasinghe R., Ding L., Anderson L., Mardis E.R., Rasko J.E.J. CTCF genetic alterations in endometrial carcinoma are pro-tumorigenic. Oncogene. 2017;36:4100–4110. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Catala C.F., Gretton S., Vostrov A., Pugacheva E., Farrar D., Ito Y., Docquier F., Kita G.X., Murrell A., Lobanenkov V., Klenova E. A novel mechanism for CTCF in the epigenetic regulation of Bax in breast cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2013;15:898–912. doi: 10.1593/neo.121948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa M., Lee J.Y., Kim M.H. CTCF negatively regulates HOXA10 expression in breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;467:828–834. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahashi, H., Kieffer Kwon, K.R., Resch, W., Vian, L., Dose, M., Stavreva, D., Hakim, O., Pruett, N., Nelson, S., Yamane, A., Qian, J., Dubois, W., Welsh, S., Phair, R.D., Pugh, B.F., Lobanenkov, V., Hager, G.L., Casellas, R., 2013. A genome-wide map of CTCF multivalency redefines the CTCF code. Cell Rep., 3, 1678–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nik-Zainal, S., Davies, H., Staaf, J., Ramakrishna, M., Glodzik, D., Zou, X., Martincorena, I., Alexandrov, L.B., Martin, S., Wedge, D.C., Van Loo, P., Ju, Y.S., Smid, M., Brinkman, A.B., Morganella, S., Aure, M.R., Lingjaerde, O.C., Langerod, A., Ringner, M., Ahn, S.M., Boyault, S., Brock, J.E., Broeks, A., Butler, A., Desmedt, C., Dirix, L., Dronov, S., Fatima, A., Foekens, J.A., Gerstung, M., Hooijer, G.K., Jang, S.J., Jones, D.R., Kim, H.Y., King, T.A., Krishnamurthy, S., Lee, H.J., Lee, J.Y., Li, Y., Mclaren, S., Menzies, A., Mustonen, V., O'Meara, S., Pauporte, I., Pivot, X., Purdie, C.A., Raine, K., Ramakrishnan, K., Rodriguez-Gonzalez, F.G., Romieu, G., Sieuwerts, A.M., Simpson, P.T., Shepherd, R., Stebbings, L., Stefansson, O.A., Teague, J., Tommasi, S., Treilleux, I., Van Den Eynden, G.G., Vermeulen, P., Vincent-Salomon, A., Yates, L., Caldas, C., Van't Veer, L., Tutt, A., Knappskog, S., Tan, B.K., Jonkers, J., Borg, A., Ueno, N.T., Sotiriou, C., Viari, A., Futteal, P.A., Campbell, P.J., Span, P.N., Van Laere, S., Lakhani, S.R., Eyfjord, J.E., Thompson, A.M., Birney, E., Stunnenberg, H.G., Van De Vijver, M.J., Martens, J.W., Borresen-Dale, A.L., Richardson, A.L., Kong, G., Thomas, G,. Stratton, M.R., 2016. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature, 534, 47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ohlsson R., Renkawitz R., Lobanenkov V. CTCF is a uniquely versatile transcription regulator linked to epigenetics and disease. Trends Genet. 2001;17:520–527. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong C.T., Corces V.G. CTCF: an architectural protein bridging genome topology and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014;15:234–246. doi: 10.1038/nrg3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orita M., Iwahana H., Kanazawa H., Hayashi K., Sekiya T. Detection of polymorphisms of human DNA by gel electrophoresis as single-strand conformation polymorphisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:2766–2770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J.E., Corces V.G. CTCF: master weaver of the genome. Cell. 2009;137:1194–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prawitt D., Enklaar T., Gartner-Rupprecht B., Spangenberg C., Oswald M., Lausch E., Schmidtke P., Reutzel D., Fees S., Lucito R., Korzon M., Brozek I., Limon J., Housman D.E., Pelletier J., Zabel B. Microdeletion of target sites for insulator protein CTCF in a chromosome 11p15 imprinting center in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and Wilms' tumor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:4085–4090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500037102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi C.F., Martensson A., Mattioli M., Dalla-Favera R., Lobanenkov V.V., Morse H.C. 3RD, CTCF functions as a critical regulator of cell-cycle arrest and death after ligation of the B cell receptor on immature B cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:633–638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237127100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasko J.E., Klenova E.M., Leon J., Filippova G.N., Loukinov D.I., Vatolin S., Robinson A.F., Hu Y.J., Ulmer J., Ward M.D., Pugacheva E.M., Neiman P.E., Morse 3RD H.C., Collins S.J., Lobanenkov V.V. Cell growth inhibition by the multifunctional multivalent zinc-finger factor CTCF. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6002–6007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Perez C., Tamborero D., Schroeder M.P., Antolin A.A., Deu-Pons J., Perez-Llamas C., Mestres J., Gonzalez-Perez A., Lopez-Bigas N. In silico prescription of anticancer drugs to cohorts of 28 tumor types reveals targeting opportunities. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:382–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabarinathan R., Mularoni L., Deu-Pons J., Gonzalez-Perez A., Lopez-Bigas N. Nucleotide excision repair is impaired by binding of transcription factors to DNA. Nature. 2016;532:264–267. doi: 10.1038/nature17661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E.F., Maniatis T. Cold Spring Harbor; N.Y., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory: 1989. Molecular cloning : a laboratory manual. [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Zhu B., Xu M., Wang X. Selection of AECOPD-specific immunomodulatory biomarkers by integrating genomics and proteomics with clinical informatics. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2018;34:109–123. doi: 10.1007/s10565-017-9405-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Shrivastava A.K. In silico characterization and transcriptomic analysis of nif family genes from Anabaena sp. PCC7120. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2017;33:467–482. doi: 10.1007/s10565-017-9388-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalaj P., Plewczynski D. Three-dimensional organization and dynamics of the genome. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2018;34:381–404. doi: 10.1007/s10565-018-9428-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai D., Gonzales F.A., Tsai Y.C., Thayer M.J., Jones P.A. Large scale mapping of methylcytosines in CTCF-binding sites in the human H19 promoter and aberrant hypomethylation in human bladder cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:2619–2626. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.23.2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terabayashi T., Hanada K. Genome instability syndromes caused by impaired DNA repair and aberrant DNA damage responses. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2018;34:337–350. doi: 10.1007/s10565-018-9429-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffen J.C., Bailey C.G., Marshall A.D., Metierre C., Feng Y., Wang Q., Watson S.L., Holst J., Rasko J.E. The cancer-testis antigen BORIS phenocopies the tumor suppressor CTCF in normal and neoplastic cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2013;133:1603–1613. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulaner G.A., Vu T.H., Li T., Hu J.F., Yao X.M., Yang Y., Gorlick R., Meyers P., Healey J., Ladanyi M., Hoffman A.R. Loss of imprinting of IGF2 and H19 in osteosarcoma is accompanied by reciprocal methylation changes of a CTCF-binding site. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:535–549. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umer H.M., Cavalli M., Dabrowski M.J., Diamanti K., Kruczyk M., Pan G., Komorowski J., Wadelius C. A Significant Regulatory Mutation Burden at a High-Affinity Position of the CTCF Motif in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Hum. Mutat. 2016;37:904–913. doi: 10.1002/humu.23014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Zhu B., Wang X. Dynamic phenotypes: illustrating a single-cell odyssey. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2017;33:423–427. doi: 10.1007/s10565-017-9400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. 2018. Clinical trans-omics: an integration of clinical phenomes with molecular multiomics. Cell Biol. Toxicol., 34, 163–166. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wu D., Wang X., Sun H. The role of mitochondria in cellular toxicity as a potential drug target. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2018;34:87–91. doi: 10.1007/s10565-018-9425-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie G.S., Hou A.R., Li L.Y., Gao Y.N., Cheng S.J. Aberrant p16 promoter hypermethylation in bronchial mucosae as a biomarker for the early detection of lung cancer. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2006;119:1469–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh A., Wei M., Golub S.B., Yamashiro D.J., Murty V.V., Tycko B. Chromosome arm 16q in Wilms tumors: unbalanced chromosomal translocations, loss of heterozygosity, and assessment of the CTCF gene. Genes Chromosom. Cancer. 2002;35:156–163. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Burke L.J., Rasko J.E., Lobanenkov V., Renkawitz R. Dynamic association of the mammalian insulator protein CTCF with centrosomes and the midbody. Exp. Cell Res. 2004;294:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]