ABSTRACT

Introduction

Dental treatment is known to trigger anxiety and fear even in fully grown adults, especially if administration of local anesthesia with a syringe is indicated. This study is aimed to evaluate whether procedures like an extraction and pulpectomy could trigger fear and anxiety in a pediatric patient and also the response of pediatric patients to other treatment modalities. Their perception toward receiving dental treatment as a whole is also evaluated. The effect of conditioning of the environment and the dentist (extractions done in second or third appointments) and its effect in decreasing the anxiety is also evaluated. The aim of the study is to evaluate the behavior of pediatric patients aged 7–17 years in response to various treatment procedures at Saveetha Dental College.

Materials and methods

The behavior of 50 children reporting to Saveetha Dental College, categorized according to the Frankl's behavior rating scale, was recorded before, during, and posttreatment.

Results

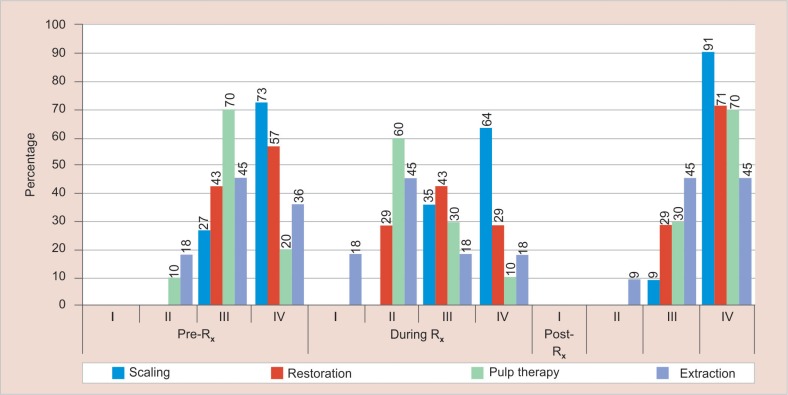

Children undergoing extractions and pulpectomies showed the most uncooperative behavior. Sixty percent of patients undergoing extraction and 45% of patients undergoing the pulp therapy showed negative behavior (rating 2) during treatment.

Conclusion

Invasive procedures like extractions and pulpectomies were procedures that brought out negative behavior in pediatric patients, especially during treatment.

How to cite this article

Sivakumar P, Gurunathan D. Behavior of Children toward Various Dental Procedures. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2019;12(5):379–384.

Keywords: Anxiety pediatric dentistry, Behavior assessment, Behavior management, Frankl's behavior scale

INTRODUCTION

Dental anxiety (DA) is a multisystem response to a stimulus that is perceived as threat or danger. It is an individual, subjective experience that varies among different people. Dental anxiety is a widespread phenomenon that ranks fifth among the most frequently feared situations and cause for stress and anxiety on the dental chair for various individuals, including adults, so it can only be imagined how much more stress it would potentially cause to a child receiving dental treatment. It can leave a profound impact on daily life and is a significant roadblock to receive dental care as it would create a deep-seated anxiety in the child to attend further appointments. The various schools of thoughts in psychology agree that anxiety is an individualized personality trait, but they have differing opinions regarding the origin and the manifestations of this trait. However, multiple variables in children's backgrounds (environment in which they grow, socioeconomic status, age, past experiences, etc.) have been identified as stimuli related to it.1 A few among the nondental markers are the problems visiting a physician, dental fear in either of the parents, maternal anxiety, and anxiety of meeting new people. Four dental markers have been identified: prior problems during a dental visit (previous traumatic experiences), dislike of the dentist, not enough time of exposure to dental situations, and fear of receiving injections.2 Dental anxiety as a manifestation during dental treatment may even originate from lack of exposure to dental environment at all like the child attending or having his or her first dental visit.3

Various methods have been used in literature for the assessment and quantification of DA. Physiological methods such as measuring muscle tension, pulse rate, and blood pressure require experience in interpretation of results from special equipment that measure these variables; projective techniques such as Corah's DA survey and modified Corah's DA survey require dexterity for carrying out interviews and scoring.4,5 Other easier methods to record anxiety include self-reporting questionnaires. The ideal method to record anxiety should be standardized and require minimal skill. It should also be easy to record. Hence, Frankl's behavior rating was used in this study to record the level of anxiety of the pediatric patients.5 This study is aimed at evaluating the behavior of pediatric patients aged 7–17 years in response to dental extractions in outpatient clinics at Saveetha Dental College.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted after approval from the Saveetha Research Board. This study was conducted in 50 children who reported to the clinics at Saveetha Dental College in the month of December 2017. The inclusion criteria were children aged between 7 years and 17 years of age and without underlying medical or systemic conditions. Informed consent was obtained from the guardians of the patients in order to record the data required for the research. The behavior was recorded in accordance with the Frankl's behavior scale,6 to compare the levels of anxiety among the patients with respect to scaling, extractions, pulpectomies, etc., before, during, and posttreatment. The patients were split into three age groups, namely 7–10 years, 11–13 years, and 14–17 years (groups I, II, and III, respectively).

FRANKL’S BEHAVIOR SCALE6

Rating 1: Definitely negative—refusal of treatment, forceful crying, fearfulness, any other overt evidence of extreme negativism.

Rating 2: Negative—reluctance to accept treatment, uncooperativeness, some evidence of negative attitude but not pronounced.

Rating 3: Positive—acceptance of treatment, cautious behavior at times, willingness to comply with the dentist, at times with reservation, but patient follows the dentist's directions cooperatively.

Rating 4: Definitely positive—good rapport with the dentist, interest in the dental procedures, laughter and enjoyment.

The behavior scale was noted only for the first procedure performed on the patient. The scores were recorded before, during, and posttreatment.

A proforma was designed for recording data pertaining to each patient (Fig. 1). The various parameters that were assessed in the proforma include the age, sex, rank of birth, residence (rural/urban), chief complaint, socioeconomic status (Kuppuswamy scale),7 dental visit (first/other), treatment, and behavior scale score rating before, during, and posttreatment.

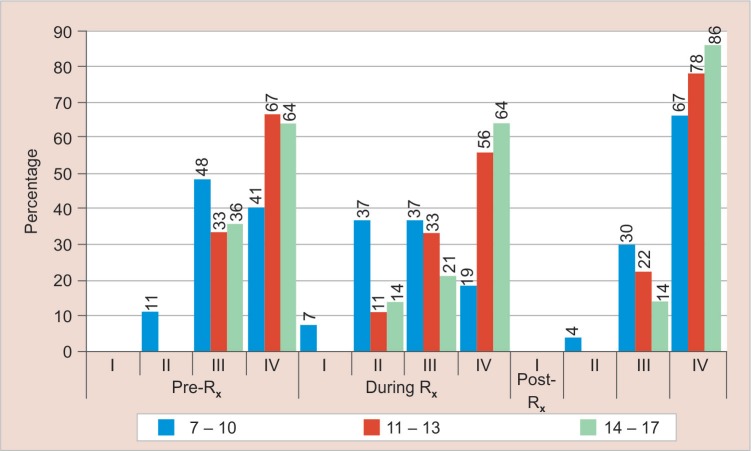

Fig. 1.

Age of the patient in relation to the percentage of the children with a particular behavior score in different phases of treatment namely pretreatment, during treatment, and posttreatment

Data were recorded in Microsoft Excel, and the various parameters were assessed separately and a relative inference was drawn out of the data analysis. In the age parameter, for more clarity, the socioeconomic status as given by modified Kuppuswamy scale in 2017 includes upper class, upper middle class, lower middle class, upper lower class, and lower class (comprehensive scoring based on the education, occupation, and income).

RESULTS

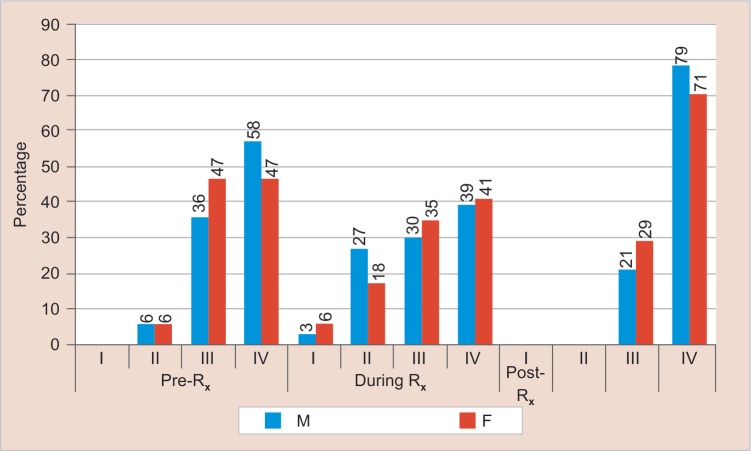

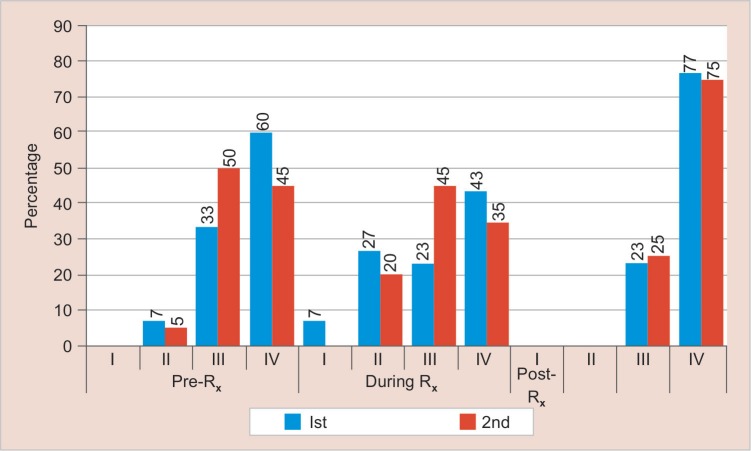

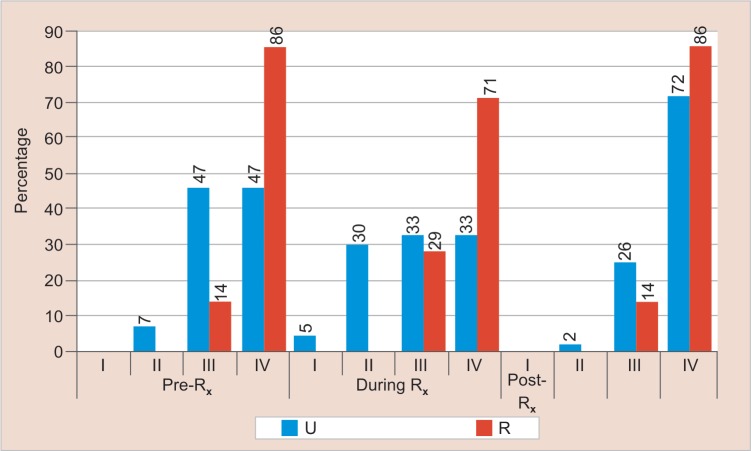

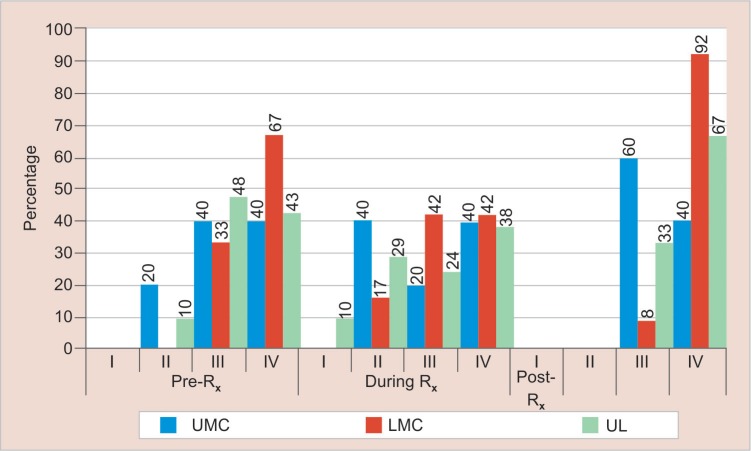

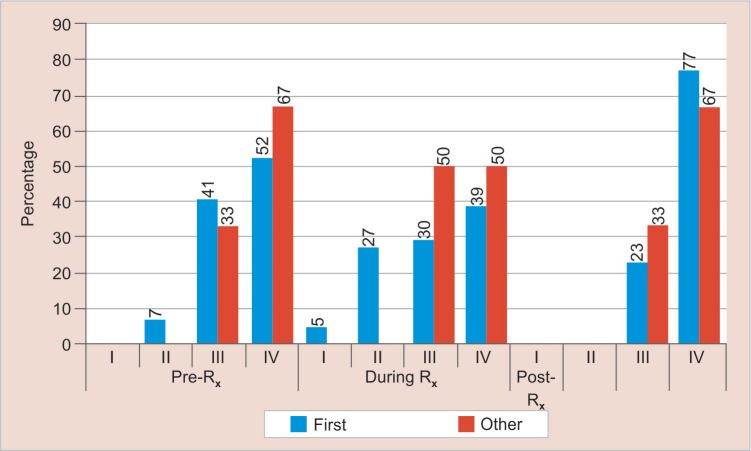

Children reported to the clinic for treatment in the 14–17 years age group showed the best behavior. Thirty-six percent of the patients in this age group belonged to category IV of the Frankl's behavior scale (Fig. 1). Males showed better cooperation posttreatment. Seventy-nine percent of the male patients belonged to category IV of the behavior scale posttreatment (Fig. 2). The first child is more cooperative before and during treatment showing 60% and 43%, respectively, in category IV on the behavior scale (Fig. 3). Children reporting to the clinic from rural areas are found to be more cooperative than those who report from urban areas. Sixty-two percent of the patients from the rural area were in category IV posttreatment (Fig. 4). Children belonging to the lower middle class in accordance with the Kuppuswamy scale showed better behavior; 92% were in category IV posttreatment (Fig. 5). In the patients who had come for their first dental visit, there was maximum cooperation posttreatment; 77% of the patients showed class IV behavior posttreatment (Fig. 5). Extraction patients showed least cooperation postoperatively (45% in class III) but pulp therapy patients showed least cooperation pre- and intraoperatively (70% and 60%, respectively) and scaling patients showed the best behavior (91% were in class IV posttreatment) (Figs 6 and 7).

Fig. 2.

Correlation of sex with the percentage of children with a particular behavior score in different phases of treatment namely pretreatment, during treatment, and posttreatment

Fig. 3.

Correlation between the rank of birth and the percentage of children with a particular behavior score in different phases of treatment namely pretreatment, during treatment, and posttreatment

Fig. 4.

Correlation between the area that the children are from (R for rural and U for urban) and the percentage of children with a particular behavior score in different phases of treatment namely pretreatment, during treatment and posttreatment

Fig. 5.

Correlation between the socioeconomic status (UMC, upper middle class; LMC, lower middle class; UL, upper lower: according to Kuppuswamy's scale) of the patient and the percentage of children with a particular behavior score in different phases of treatment namely pretreatment, during treatment, and posttreatment

Fig. 6.

Correlation between the number of dental visits (first dental visit, other) of the child and the percentage of children with a particular behavior score in different phases of treatment namely pretreatment, during treatment, and posttreatment

Fig. 7.

Correlation between the treatment procedure being performed (scaling, restoration, pulp therapy, and extraction) and the percentage of children with a particular behavior score in different phases of treatment namely pretreatment, during treatment, and posttreatment

DISCUSSION

Dental anxiety is a very common phenomenon observed in dental practice especially among children who visit the dental clinic for treatment. Though there are various methods to quantify DA among pediatric dental patients, one of the most widely used systems was introduced by Frankl et al. in 1962. It is referred to as the Frankl's behavioral rating scale. The scale divides observed behavior into four categories, ranging from definitely positive to definitely negative. The Frankl's classification method is often considered the gold standard in clinical rating scales, mainly as a result of its wide usage and acceptance in pediatric dentistry research. In general, a maximum number of patients reporting to the clinics showed a cooperative behavior intraoperatively. Older patients showed a better cooperation (14–17 years) when compared to the younger age groups (7–10, 11–13 years of age). Because of the increase in the age, they are able to understand and comprehend the instructions of the dentist better, and voice out their feelings and perceptions clearly, and there is a possibility of them to have had more dental visits and hence show lesser DA. Male patients showed better cooperation intra- and postoperatively. First-born children were found to be more cooperative before and during treatment. Rank of birth is also an important factor in determining the behavioral patterns as, first-born children are usually found to be more flexible and cooperative. Children belonging to rural areas and the lower middle class were also extremely cooperative intra- and postoperatively. In private clinics, a completely different scenario can be observed where most of the children reporting for treatment are spoilt rotten and have a very uncooperative behavior. Extraction and pulp therapy patients showed the least cooperation; this is due to the fact that both these procedures are invasive and involve administration of local anesthesia, loss of blood, and the child may also experience pain or be forced to stay cooperative during treatment.8 And also in case of an extraction there is loss of the tooth, and the child experiences a psychological insult.9 There are various factors that could trigger an uncooperative behavior like local anesthesia, unpleasant and unfamiliar tastes, fear of blood, etc.10,11

Previously, a study has observed that children show a specific anxiety to local anesthesia due to the use of sharp instruments and perceive it as an overwhelming sensory experience.12 The main complaints from the children undergoing treatment are cracking sounds and a wiggling sensation of the tooth.13 The various sensations felt by the child due to manipulation of teeth with instruments, sounds heard during extraction, and the pressure felt are misinterpreted as pain by the child.14 These factors that sensitize the child to pain psychologically are more important than pain itself when it comes to the behavioral patterns of the children during the extraction procedures.15 A longitudinal study that has been conducted suggests that exposure to a continued dental experience has a direct correlation with the decrease in DA levels, regardless of the procedure being performed.16 When the children become accustomed to the dental environment, they develop the sense to differentiate stressful from nonstressful behaviors.17,18 This may explain the fact that the child showed better cooperative behavior postoperatively. This is also similar to the study by Sjögren et al.19 A study by Buchanan et al. suggested that pain during any procedure may cause a deep-seated anxiety in the child20 and cause worsened behavior in subsequent appointments.21 This situation makes it all the more necessary for the dental practitioner to perform procedures with lesser pain and also use various behavior management strategies in order to keep the patient comfortable.22

A study by Aminabadi et al. in 2011 has reported problematic behaviors in follow-up appointments after extractions, even for less invasive procedure like restorations.23 Behavioral problems while dental procedures are performed are not related exclusively to the dental procedure being performed and may depend on a plethora of various other characteristics like child–dentist relationship, maternal characteristics,24 personality traits,25,26 and general fears.27 Thus, the dentists play an important role in predicting and dealing with the child's anxiety for eliciting a better behavior, work alongside with the relatives or the guardians, and also patiently deal with their doubts and anxieties.

Previous studies have reported an increased prevalence of pain and behavioral problems in girls.28,29 This may be due to the biological and sociological differences wherein the girl children show their emotions more easily. A previous study has reported that girls experience more pain during the local anesthesia than during the extraction.

Studies have also reported the fact that younger patients are most difficult to manage on a dental chair.30,31

The limitation of the study is that the sample size was low and the general majority of the patients were from a lower economic strata, and that could be a major variant that expresses itself in the children behavior patterns. But the evaluation of the child behavior was carried out by one person throughout the course of the study to avoid changes in perceptions and varied readings. Also, a simple yet standardized behavior rating scale (Frankl's behavior rating scale) was used in the study as the basis for evaluation and comparison with all parameters.

CONCLUSION

In the study conducted, it can be concluded that invasive procedures like extraction and the pulp therapy showed maximum uncooperative behavior in children, especially in the younger age groups (7–10 years). But there was a generalized cooperative behavior in most of the cases, pre-, intra-, and postoperatively, though the scenario may have been different if the study was conducted in a private practice. The study also highlighted the importance of adequate behavior management techniques and skills of the dentist to build a good rapport with the children and their guardian for more cooperation and a better treatment outcome.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Klingberg G, Berggen U, et al. Child Dental fear: Cause related factors and clinical effects. Eur J Oral Sci. 1995;103:405–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1995.tb01865.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peretz B, Nazarian Y, et al. Dental anxiety in a student's pediatric dental clinic: Children, parents and students. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2004;14:192–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2004.00545.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal M, Das UM. Dental anxiety prediction using Venham Picture test: a preliminary cross-sectional study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2013;31:22–24. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.112397. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shetty RM, Khandelwal M, et al. RMS Pictorial Scale (RMS-PS): An innovative scale for the assessment of child's dental anxiety. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2015;33:48–52. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.149006. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aartman IH, van Everdingen T, et al. Self-report measurements of dental anxiety and fear in children: a critical assessment. ASDC J Dent Child. 1998;65:252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frankl SN, Shiere FR, et al. Should the parent remain in the operatory? J Dent Child. 1962;29:150–163. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh T, Sharma S, et al. Socio-economic status scales updated for 2017. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017;5:3264–3267. doi: 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20173029. DOI: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cademartori MG, Da Rosa DP, et al. Validity of the Brazilian version of the Venham's behavior rating scale. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2017;27:120–127. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12231. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venham LL, Gaulin-Kremer E, et al. Interval rating scales for children's dental anxiety and uncooperative behavior. Pediatr Dent. 1980;2:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro DN. Reactions of children to oral surgery experience. J Dent Child. 1967;34:97–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armfield JM. A preliminary investigation of the relationship of dental fear to other specific fears, general fearfulness, disgust sensitivity and harm sensitivity. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36:128–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00379.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan AG, Rodd HD, et al. Children's experiences of dental anxiety. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2017;27:87–97. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12238. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meechan JG. Pain control in local analgesia. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2009;10:71–76. doi: 10.1007/BF03321603. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naoumova J, Kjellberg H, et al. Pain, discomfort, and use of analgesics following the extraction of primary canines in children with palatally displaced canines. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2012;22:17–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01152.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams PE. Fear, pain and anesthesia. J Oral Surg (Chic) 1947;5:141–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramos-Jorge J, Marques LS, et al. Degree of dental anxiety in children with and without toothache: Prospective assessment. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2013;23:125–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2012.01234.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howitt JW, Stricker G. Sequential changes in response to dental procedures. J Dent Res. 1970;49:1074–1077. doi: 10.1177/00220345700490051201. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venham L, Bengston D, et al. Children's response to sequential dental visits. J Dent Res. 1977;56:454–459. doi: 10.1177/00220345770560050101. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sjögren A, Arnrup K, et al. Pain and fear in connection to orthodontic extractions of deciduous canines. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010;20:193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2010.01040.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchanan H, Niven N. Validation of a facial image scale to assess child dental anxiety. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002;12:47–52. doi: 10.1046/j.0960-7439.2001.00322.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Versloot J, Veerkamp JS, et al. Pain behaviour and distress in children during two sequential dental visits: Comparing a computerised anesthesia delivery system and a traditional syringe. Br Dent J. 2008;205:E2. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.414. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleinknecht RA, Lenz J. Blood/injury fear, fainting and avoidance of medically-related situations: A family correspondence study. Behav Res Ther. 1989;27:537–547. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90088-0. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aminabadi NA, Ghoreishizadeh A, et al. Can drawing be considered a projective measure for children's distress in paediatric dentistry? Int J Paediatr Dent. 2011;21:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2010.01072.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliveira MM, Colares V. The relationship between dental anxiety and dental pain in children aged 18 to 59 months: a study in Recife, Pernambuco State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25:743–750. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2009000400005. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ten Berge M, Veerkamp JS, et al. Childhood dental fear in the Netherlands: Prevalence and normative data. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30:101–107. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.300203.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chellappah NK, Vignehsa H, et al. Prevalence of dental anxiety and fear in children in Singapore. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1990;18:269–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1990.tb00075.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bankole OO, Aderinokun GA, et al. Maternal and child's anxiety – Effect on child's behaviour at dental appointments and treatments. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2002;31:349–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z. Sex differences in pain perception. Gend Med. 2005;2:137–145. doi: 10.1016/S1550-8579(05)80042-7. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klaassen MA, Veerkamp JS, et al. Changes in children's dental fear: a longitudinal study. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2008;9(1):29–35. doi: 10.1007/BF03262653. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ravikumar D, Sujatha S. Break the barrier: Bringing children with special health care needs into mainstream dentistry. Int J Pedod Rehabil. 2016;1:42–44. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salma AN, Ramakrishnan M. Use of anesthesia in pediatric dentistry: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Pedod Rehabil. 2016;1:5–9. [Google Scholar]