World Health Organization has declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a pandemic in March, 2020. The studies have shown 19.7%–27.8% of COVID-19 patients developed myocardial injury with significantly high mortality (hazard ratio, 4.26 [95% CI, 1.92–9.49]).1, 2, 3 Initial studies on COVID-19 focused on cardiovascular and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) as a cause of morbidity and mortality; however, recent study by Grillet and coworkers in 100 patients of 280 hospitalized patients of COVID-19, revealed 23% incidence of pulmonary embolism (PE) in these patients, and concluded that patient with PE required mechanical ventilation more often than without PE (74% vs 29%, p < .001) (OR = 3.8 [95% CI, 1.02–15], p = .049).4 In another study by Poissey et al in 107 first consecutive confirmed COVID-19 patients, incidence of PE within a median time of 6 days of ICU admission was 20.6%. The frequency of PE was twice higher than the control group (20.6% vs 6.1%; absolute increase risk of 14.4% [95% CI, 6.1–22.8%]). Nonetheless, most of the patients were obese, which might be a confounding factor.5 Anecdotal reports showed the venous thrombo-emblism in COVID-19.6

The predominant reason for the poor detection rates of PE in COVID-19 pneumonia is inability to perform computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) because of the risk of virus aerosolization, lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), and difficulty in shifting mechanical ventilated patient.

Pathogenesis of pulmonary embolism

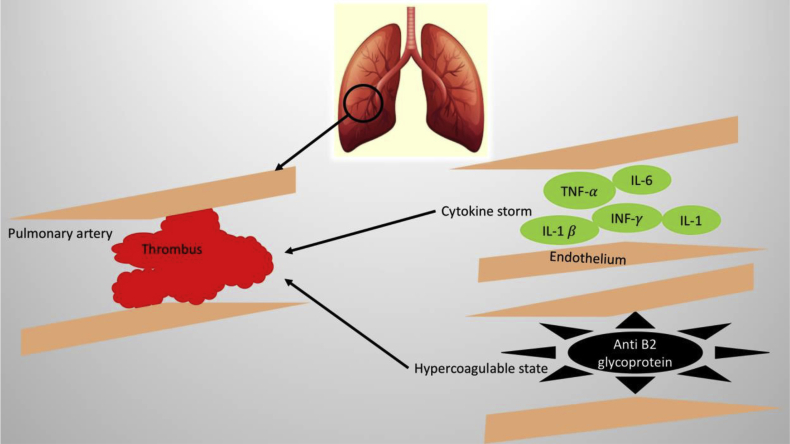

The pathogenesis of PE in COVID-19 is multifactorial (Fig. 1). Viral induced cytokine storm with increased interleukin 1(IL-1), interleukin 2 (IL-2), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor (TNF- α), interferon γ (INF-γ), monocyte chemoattractant protein, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), results in a hyper inflammatory state in the circulatory system.3 The endothelial dysfunction acts as a milieu for the formation of thrombus in the pulmonary arteries. A recently published case from China discussed about hypercoagulable state in COVID-19 patients.7

Fig. 1.

Possible hypothesis of pulmonary embolism in COVID-19. Cytokine surge secondary to viremia causes endothelial dysfunction. Presence of anti-β2 glycoprotein/antiphospholipid antibodies in COVID-19 could be a potential cause of pulmonary thrombosis. IL-1: Interleukin-1, IL-1β: Interleukin-1β, IL-6: Interleukin-6, Interferon-γ: Interferon-γ, and TNF-α:Tumor necrosis factor-α.

The clinical diagnosis of PE in COVID-19 pneumonia is challenging because D-dimer can be spuriously elevated in the patients with viremia. D-dimer is also considered as predictor of mortality in COVID-19.2 Routine venous compression ultrasonography, echocardiography, and CTPA are not possible, due to the risk of transmission of disease. Henceforth, unexplained hypotension, tachycardia, and worsening hypoxia in previously stable patients should be taken seriously, and PE should be kept as differential while managing such patients.

International society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) has released guidelines on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19 patients.8 However, given the limited availability of data regarding the pathogenesis of PE in COVID-19 patients, several questions arise and remain yet to be answered:

-

A.

What is the benefit of prophylactic heparin therapy in patients with COVID-19 admitted in the intensive care unit?

-

B.

How to diagnose and manage subacute pulmonary embolism in COVID-19?

Declaration of Competing Interest

We have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Shi S., Qin M., Shen B. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Mar 25 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo T., Fan Y., Chen M. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Mar doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh S., Desai R. COVID-19 and new-onset arrhythmia. J Arrhythmia. 2020 Apr doi: 10.1002/joa3.12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grillet F., Behr J., Calame P., Aubry S., Delabrousse E. Acute pulmonary embolism associated with COVID-19 pneumonia detected by pulmonary CT angiography. Radiology. 2020 Apr23:201544. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poissy J., Goutay J., Caplan M. Pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: awareness of an increased prevalence. Circulation. 2020 April 22 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danzi G.B., Loffi M., Galeazzi G., Gherbesi E. Acute pulmonary embolism and COVID-19 pneumonia: a random association? Eur Heart J. 2020 Mar 30 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa254. ehaa254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y., Xiao M., Zhang S. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr12;382(17):e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thachil J., Tang N., Gando S. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemostasis. 2020 Mar 25 doi: 10.1111/jth.14810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]