Significance

Imaging the very subtle deformations of neurons during the action potential requires subnanometer axial precision with submillisecond temporal resolution. Until now, the magnitude, time course, and spatial features of such deformations over the entire mammalian neuron were largely unknown. Using the full-field interferometric imaging and spike-triggered averaging, we demonstrate the spatiotemporal dynamics of the cellular deformations over the entire somas and neurites accompanying the action potential. Mechanics of these deformations can be explained by voltage dependence of the membrane tension originating from the lateral repulsion of ions accumulating near the membrane surface. Our imaging methodology provides guidance toward wide-field label-free imaging of the neural signaling.

Keywords: electromotility, quantitative phase imaging, action potential, single-cell mechanics

Abstract

Neurons undergo nanometer-scale deformations during action potentials, and the underlying mechanism has been actively debated for decades. Previous observations were limited to a single spot or the cell boundary, while movement across the entire neuron during the action potential remained unclear. Here we report full-field imaging of cellular deformations accompanying the action potential in mammalian neuron somas (−1.8 to 1.4 nm) and neurites (−0.7 to 0.9 nm), using high-speed quantitative phase imaging with a temporal resolution of 0.1 ms and an optical path length sensitivity of <4 pm per pixel. The spike-triggered average, synchronized to electrical recording, demonstrates that the time course of the optical phase changes closely matches the dynamics of the electrical signal. Utilizing the spatial and temporal correlations of the phase signals across the cell, we enhance the detection and segmentation of spiking cells compared to the shot-noise–limited performance of single pixels. Using three-dimensional (3D) cellular morphology extracted via confocal microscopy, we demonstrate that the voltage-dependent changes in the membrane tension induced by ionic repulsion can explain the magnitude, time course, and spatial features of the phase imaging. Our full-field observations of the spike-induced deformations shed light upon the electromechanical coupling mechanism in electrogenic cells and open the door to noninvasive label-free imaging of neural signaling.

Minute (nanometer-scale) cellular deformations accompanying the action potential have been observed in crustacean nerves (0.3 to 10 nm) (1–4), in squid giant axon (1 nm) (5, 6), and recently in mammalian neurons (0.2 to 0.4 nm) (7, 8). These findings illustrate that rapid changes in transmembrane voltage due to the opening and closing of the voltage-gated ion channels have mechanical consequences accompanying the action potential and other changes in transmembrane voltage, which may allow noninvasive label-free imaging of neural signals (9). However, detecting the nanometer-scale millisecond-long deformations in biological cells is very challenging, and previous observations were limited to a single spot on the axon (1–7) or to the boundary of the cell soma (8). Until now, the entire picture of how neurons move during the action potential was unclear, and the underlying mechanism remains poorly understood. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the membrane displacement during the action potential in axons, including electrostriction (10), converse flexoelectricity (11, 12), and soliton wave (13, 14). High-speed and wide-field imaging of the spatiotemporal dynamics of neuronal deformations during the action potential, as achieved in this work, should add an additional tool to help resolve the electromechanical coupling mechanism.

Not only neurons, but also other cells, such as HEK-293, deform when their membrane potential is altered (9, 15–19). Atomic force microscopy showed that the membrane displacement in HEK-293 cells is proportional to the membrane potential, and a hypothesis was put forth that such displacements are due to voltage-dependent membrane tension originating in the lateral repulsion of mobile ions in the Debye layers (15). This linear dependence was later confirmed by measurements using piezoelectric nanoribbons (16), quantitative phase imaging (QPI) (18), and plasmonic imaging (19). Under this hypothesis, changes in the membrane tension with varying cell potential lead to a pressure imbalance on the cell surface, as described by the Young–Laplace law, thus deforming the cell into a new shape balancing the membrane tension, hydrostatic pressure, and the elastic force from the cytoskeleton. Careful analysis of this electromechanical model calls for a full-field imaging of the whole cell with submillisecond temporal resolution and angstrom-scale membrane displacement sensitivity.

In this study, we report the full-field imaging of neuron deformations accompanying the action potential (termed spike-induced deformation) using high-speed QPI (9, 20) with spike-triggered averaging (STA), which enables 0.1-ms temporal resolution and an axial path length sensitivity of 4 pm per pixel. Synchronization was performed first via multielectrode array (MEA) detecting spontaneous firing in real time and, subsequently for increased numbers of observations, by synchronizing the QPI to light pulses in optogenetic stimulation (21, 22). To evaluate the membrane-tension–based model as the underlying mechanism, we compare the experimental results to an electromechanical model of spike-induced deformation by applying the voltage-dependent membrane tension to the “cortical shell–liquid core” model (23–25), using the three-dimensional (3D) cellular morphology mapped by confocal imaging.

Results

Noise Reduction via STA.

In addition to offering intrinsic phase contrast of biological cells without exogenous markers, QPI provides an exquisitely precise quantitative metric for the optical path difference (26), which allows full-field imaging of the nanometer-scale membrane displacements along the optical axis. In our system, a transparent MEA with cultured neurons was mounted on the QPI microscope and illuminated by a collimated beam incident from the top. Cellular deformations change the incident wavefront distortions, resulting in spatial variations of the interferogram imaged by the high-speed camera (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Quantitative phase microscopy combined with microelectrode array recording for spike-triggered average imaging of cellular deformations during action potentials. (A) The collimated incident wavefront accumulates spatially varying phase changes as it passes through cells. Transparent MEA provides simultaneous recording of electrical signals. (B) A spike-triggered average movie is generated by synchronizing the image frames to a preceding electrical spike and averaging multiple events, and electrodes in the movies are masked out with the black dots. (C) Cellular deformations are visualized as the difference between each frame and the initial frame, revealing the nanometer-scale deformation across a neuron. (Scale bar: .) (D) The 4D STAs encode the displacements of the objects across the field of view, and one point sliced through the marker in time shows the temporal dynamics. (E) Noise in the resulting STAs scales with the number of averages, , according to the theoretical .

Sensitivity to such wavefront distortions, or optical phase changes, is limited by the shot noise of the detectors, in the absence of other more dominant interference (27). Given the 11,000-electron well capacity in our camera, the phase noise from a single shot in our system is 2 mrad, which is 60 times larger than the sensitivity needed to image the nanometer-scale spike-induced deformation in transmission geometry. To reduce the phase noise, we implemented STA. Timing of the electrical spikes recorded by the MEA was used to synchronize the beginning of several thousand phase movies, each recording the full-field phase changes during a single action potential. These movies were synchronized and averaged into a single STA movie (Fig. 1B), where the subnanometer spike-induced deformation could be revealed with a temporal resolution of 0.1 ms in a field of view (FOV) of (Fig. 1C and Movie S1). Assuming a refractive index difference of between the cytoplasm and the extracellular medium, the membrane displacement can be obtained by

| [1] |

where is the center wavelength of the QPI system (819 nm) and OPL is the change in the optical path length (OPL).

The STA extracts the common characteristics of the signals since it averages out any transient features unique to particular events, and it relies on repeatability of the phase signal and phase stability of the system, as the measurement must remain in a shot-noise–limited regime. Ideally, if no correlated noise is present in the STA, the phase noise should scale with the number of averages as , meaning that reducing the phase noise by >60 times requires at least 3,600 averages. Due to the slow, camera-limited data transfer of the very large volume of interferograms (0.5 TB), continuous recording of spontaneous firing yields only 185 s of measurements for each hour of operation. At an observed spiking rate of 2 to 8 Hz, this would yield only 370 to 1,480 spikes, with 99.2% of the captured data being empty frames without spikes. Therefore, for spontaneously spiking neurons, a crucial step was to detect bursts of activity on the MEA in real time to selectively record only the highest-density movies to prioritize the limited data storage bandwidth (Materials and Methods), which resulted in a 4- to 11-fold increase in the number of averages. With optogenetically controlled recordings, the data collection efficiency improved 10- to 15-fold since we captured only the 6- to 10-ms movie segments around each spike time.

The STA movie is a rich four-dimensional (4D) dataset that represents the spatial and temporal dynamics of the cellular deformations. Each frame encodes deformation as a function of position . This is illustrated conceptually in Fig. 1D, and the markers show that slicing through one point in time yields the local temporal dynamics as a plot which can be compared to electrical waveforms recorded via extracellular or intracellular electrodes.

To achieve subnanometer sensitivity in the presence of large and ubiquitous interference, including environmental vibrations and particles drifting through the FOV, sophisticated experimental procedures, data filtering, and image processing are required. Various corrections, co-optimized between the physical optics and the offline data analysis, resulted in a shot-noise–limited performance, which was confirmed by the fact that the noise level scaled with the theoretical improvement from averaging the uncorrelated noise (Fig. 1E). An optical path length sensitivity of <4 pm per pixel was achieved by the STA with 9,091 spikes averaged, corresponding to a membrane displacement sensitivity of <0.2 nm per pixel, given that the refractive index difference is 0.02 (SI Appendix). Synchronization and phase stability required for averaging without compromising this shot-noise–limited performance go hand in hand with the rest of the system design, as described below.

STA Phase Imaging Reveals Fast Spike-Induced Cellular Deformations.

We first investigated spike-induced deformations during spontaneous action potentials, in the absence of external stimulation. Primary cortical neurons were cultured on MEAs with a cell density of 1,200 to 2,000 cells/. Starting from 7 d in vitro (DIV), sparse spontaneous spiking could be observed in electrical recordings. At 17 to 21 DIV, we recorded the QPI phase movies and electrical signals with real-time burst detection for 1 h. In a representative experiment, after averaging over 7,586 spikes, the STA phase movie revealed fast nanometer-scale cellular deformations over the entire soma and neurites during the action potential. Most of the soma rose up, while the left boundary fell as the membrane depolarized (Fig. 1C and Movie S1).

Spatial averaging of the phase signal over the soma, considering the polarity of the phase shift in each area, improved the peak signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) to 21.5, yielding a high-fidelity time course of the phase changes, including a quick onset (0.2 ms) to 0.12 mrad followed by a 1-ms relaxation (Fig. 2A). The time derivative of the phase signal with an inverted sign closely matches the electrical waveform on extracellular electrodes (Fig. 2A). Latency between the phase signal and the electrical signal was not detected, which means it was below our time resolution of 0.1 ms.

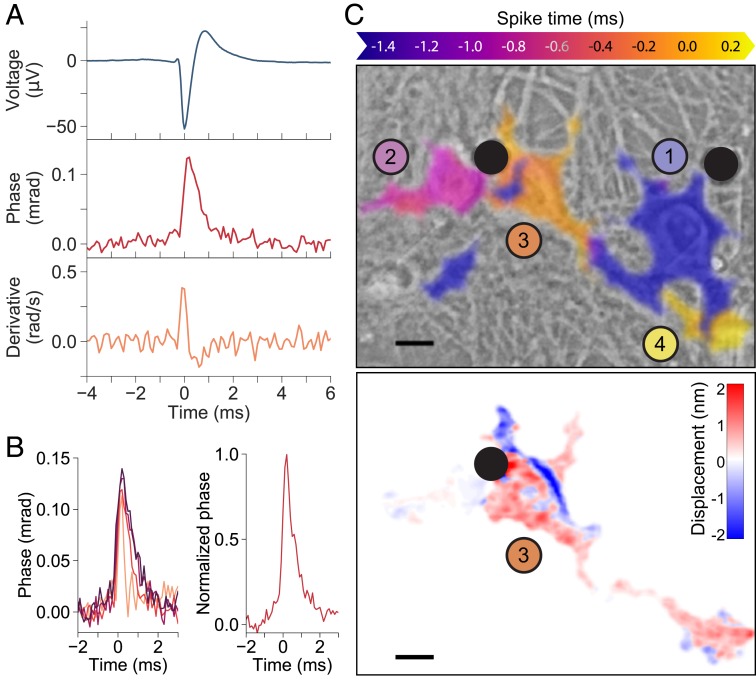

Fig. 2.

Synchronized QPI/MEA measurements of neuronal deformations. (A, Top) Extracellular electrical recording used to synchronize video frames. (A, Middle) Spike-triggered average phase change across the cell during the action potential. (A, Bottom) Time derivative of the phase signal matches the electrical waveform with a negative sign. (B, Left) Time course of the phase signals from four cells, showing a quick onset to 0.12 mrad (average) followed by a 1- to 2-ms relaxation. (B, Right) Averaging all of the datasets yields a spiking template for matched filter detection of spikes. (C) The spiking template helps detect the spike timing across the field of view (Top), exploiting temporal and spatial adjacency of spiking signals to segment individual cells from the background. Filled black circles indicate the location of the MEA electrodes, and the colored, numbered circles correspond to the time scale at the top of the figure, indicating relative spiking time, referenced to spike timing number 3. C, Bottom shows the displacements on the third neuron at ms (peak of the spike). (Scale bar: .)

Phase changes across four neurons are shown in Fig. 2 B, Left, all consistent with the expected temporal dynamics of the action potentials. Because the phase signals were similar across all measured cells, a characteristic template for the spike detection can be obtained by averaging across the datasets (Fig. 2 B, Right). The spiking template was generated from only the areas of higher SNR in multiple cells. Using this template as a match filter on every pixel in the FOV across time improved the spike detection and helped reject noisy areas in the image. Precise detection of the spike time allows separation of adjacent cells that fired in succession a few tenths of a millisecond apart. The resulting segmentation, shown in Fig. 2 C, Top and in Movie S2, illustrates these four cells in a FOV spiking in sequence over the course of 2 ms. Each neuron was segmented, overlaid on a phase-contrast view, and color coded to represent the spike time, demonstrating the signal flow as the action potential moves from one neuron, along its processes, to another neuron spiking later. The frame from the STA phase movie corresponding to , the spike time of the third cell, is shown at the bottom of Fig. 2 C.

Moreover, template matching allows computational interpolation of the temporal resolution of the spike imaging from our native 0.1 ms, defined by the camera, down to , as previously demonstrated with genetically encoded voltage indicators (28). As shown in Movie S3, with this method, the fast action potential propagation can be predicted with a temporal resolution of .

Spatial Features of the Spike-Induced Deformations.

The measurement throughput on the MEA is defined by the prevalence of neurons adjacent to electrodes and firing individually. Good optical isolation of a cell required for QPI imaging contradicts the requirement of a high cell density necessary for a high spontaneous spiking rate. These contradicting requirements resulted in relatively low yield of the QPI recordings of spontaneous firing in neuronal cultures. Using optogenetic stimulation (22) and interferometric recordings synchronized to the optical stimuli, we obviated the need for the MEA. This approach relied on stable stimulation at the 5-Hz rate (>99% success in eliciting spikes) with a small jitter (0.1 ms) between the elicited spikes and the optical stimulus, as characterized by earlier MEA measurements (; SI Appendix, Fig. S1). With this synchronization, we did not have to record electrical waveforms, and therefore neurons could be cultured on coverslips instead of thicker MEAs, which enabled high-resolution confocal microscopy for 3D morphology mapping.

However, optical stimulation resulted in a photothermal phase artifact (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and Movie S4) due to absorption of green light by the phenol red in the cell culture medium. We measured the artifact in the background of each STA via spatial averaging, which was then subtracted from the STA phase movie, resulting in undisturbed spike-induced phase changes (Materials and Methods). The photothermal artifact matched the curve predicted by the finite-element modeling (COMSOL Multiphysics software) based on the temperature dependence of the refractive index of water (29).

With the photothermal artifacts removed, we acquired a large number of datasets imaging spike-induced deformations ( for somas, for neurites). Fig. 3A shows the magnitude of the deformations in cell somas and the surrounding neurites, quantified as a maximum positive displacement (1.4 0.2 nm for somas, mean SD; 0.9 0.2 nm for neurites), a minimum negative displacement (−1.8 0.6 nm for somas; −0.7 0.3 nm for neurites), and the mean absolute displacement (0.4 0.1 nm for somas). The latter was obtained by spatially averaging the absolute phase change over the entire soma.

Fig. 3.

Magnitude and spatial features of the spike-induced deformations over multiple cells. (A) Statistics of the displacements across cell somas () and neurites (): maximum positive (Max), minimum negative (Min), and mean absolute displacements (Mean). (B) Histograms of the lateral distances from the cell centroid to the locations exhibiting maximum positive displacements, minimum negative displacements, and maximum absolute displacements (Abs) (). The distances are linearly normalized between the centroids (0) and the cell boundaries (1). (C) Histograms of the area ratios of the positive displacement regions to the negative displacement regions. No cells had a ratio below 1, meaning that areas of positive displacements are larger than the negative areas in every cell (). (D) Confocal image (Top) and its 3D perspective (Middle), compared to the spike-induced deformation of a neuron (Bottom). The arrow points to a flat portion of the neurite which becomes more spherical, with its center moving up and the two boundaries shifting down. (Scale bar: .)

In terms of spatial distribution, we observed a general trend of cells becoming more spherical during depolarization. The change is on a nanometer scale, so the word “spherical” is just an indication of the trend toward minimizing the cell’s surface area. An example of this is shown in Fig. 3D. The top of the steep cell soma was moving down, while the periphery was getting thicker. A flat part of a neurite (indicated by an arrow) was also becoming more spherical: Its middle portion was moving up while the edges were shifting down. Additional examples are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S3. Intriguingly, we found that a large fraction (71%, ) of the maximum absolute displacements occurred in the regions near the cell boundaries, mainly contributed from the negative displacements (Fig. 3B); while every cell exhibited a larger positive displacement area than the negative displacement area (Fig. 3C, ). Theoretically, these observations are consistent with a general picture of cell centers moving up while boundaries move down or cells shifting from one side to the other to become more spherical. From an engineering perspective, it also suggests that the boundary regions of neurons should be given a high priority for detecting the maximum signal for label-free imaging of action potentials.

Modeling the Voltage-Induced Cellular Deformation.

Our observation that the cells are becoming more spherical during membrane depolarization is in line with the voltage-dependent membrane tension model (15), which predicts a quasi-linear relationship between the membrane tension and membrane potential:

| [2] |

According to this model, the membrane tension should increase by for a 100-mV depolarization, given the surface charge density measured in neurons (30). Using the Young–Laplace law, the shape of biological cells is determined by the balance of hydrostatic pressure , membrane tension , and cortex tension (23, 31). Membrane tension is composed of the lipid bilayer tension and the lateral repulsion of ions on both sides of the membrane. The mean surface curvature on the cell surface can be determined as

| [3] |

where

| [4] |

According to this model, increase in the surface tension during membrane depolarization will lead to an increase in the pressure toward the intracellular space, proportional to the surface curvature; i.e., areas with lower curvature will generate less pressure. For cell somas, this effect will drive the mean curvature on various parts of the cell to equalize, i.e., become more spherical.

To model the spike-induced deformation quantitatively, we applied the voltage-dependent membrane tension to a cortical shell–liquid core model of a single cell (Fig. 4A). The thickness and the Young’s modulus for the actin cortex were assumed to be 100 nm and 1 MPa (32, 33), respectively. The viscosity of the cytoplasm was assumed to be 2.5 mPas (34) and the maximum membrane tension change was set to /m. Perfectly spherical cells do not deform at all in this model, and the greater the aspect ratio and the overall size, the greater the displacements toward more spherical shape. This simple model yielded the same magnitude and distribution of positive and negative displacements as in our observations in cells.

Fig. 4.

Mechanical model based on the voltage-dependent membrane tension predicts a deformation toward a more spherical shape during the action potential, with less than 0.1 ms latency. (A) The “cortical shell–liquid core” mechanical model of the cell transduces surface tension changes into cell deformation. (B) With a physiological Young’s modulus (1 MPa), the predicted time course (10 latency) matches the lack of observable delay between the deformation and the electrical waveform. Much softer structures, however, would introduce significant delay.

This model links the response time, i.e., how quickly the spike-induced deformation will follow the action potential, to the cell stiffness (Young’s modulus). Fig. 4B shows that with a Young’s modulus in the typical range from the literature (25, 32, 33, 35, 36) (1 MPa), a cell responds to the tension change with a response time of 10 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), tracking the underlying membrane potential closely, as we observe in experiments. In contrast, with low Young’s modulus (1 kPa), the model predicts a delayed response, as the much softer membrane deforms the cell much slower, similar to earlier observations in Chara internodes with detached cell walls (37). A Young’s modulus of 50 kPa shifts the deformation response past the 0.1-ms temporal resolution of our measurements, indicating that moduli below that limit would introduce a detectable delay relative to the electrical pulse, which was not observed in our experiments.

Since the surface tension increase will make the cell more spherical, the deformation pattern should be largely dependent on the cell shape. To compare model predictions with experimental images, we acquired QPI and 3D confocal images of the same cell (Fig. 5A) (38) and reconstructed its geometry for finite-element modeling (Fig. 5B). Neurites were truncated as indicated by the white outline in Fig. 5A and as shown in a 3D view in Fig. 5B. For a QPI imaging model, we incorporated the halo effect, an artifact due to the incomplete low-pass filtering of the reference beam (39, 40) (SI Appendix). The measured and predicted deformation patterns, shown in Fig. 5 C and D, exhibit similar magnitudes of displacements along with a general match of features, such as the negative region at the top of the soma and the band of positive displacements in a crescent through the middle. Additional examples are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S5 and Movie S5.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the modeled and experimental spike-induced deformations in the same cell. (A) Confocal image of a cultured neuron with the segmented area outlined in white. (Scale bar: .) (B) Three-dimensional model of the cell segmented from the confocal image stacks. (C) QPI of the spike-induced deformation of the same cell. (D) Simulated deformations from the model, combined with a QPI imaging model that incorporates the halo effect and the refractive index difference.

Discussion

Interferometric detection of the spike-induced deformation offers a fast, intrinsic probe for label-free imaging of action potentials. Exogenous fluorescent indicators require invasive interventions to load the cells with optical markers and suffer from photobleaching (41) and heating limitations (28). In addition, the slow response of calcium imaging [>100 ms decay (42)], makes it inadequate for revealing closely spaced action potentials. Response time of the spike-induced deformation reported here (<0.1 ms) is much better than those of even the genetically encoded voltage indicators, the response times of which are on the order of 1 ms (42, 43).

However, interferometric imaging of single action potentials in neurons calls for further SNR enhancement. This could be addressed using reflection geometry (like optical coherence tomography [OCT]), in which the signal benefits from the double pass and is not attenuated by the refractive index difference between the cell and the medium, as in transmission QPI. Given a refractive index difference around 0.02 and a refractive index of 1.33 for water, a 133-fold improvement is expected in the phase change during the spike (about 13.3 mrad) in reflection mode. In OCT, this phase change corresponds to the phase noise floor at a reasonable SNR of 38 dB (44). The key question, though, is the strength of the backscattered signal. At the medium-cell boundary, the reflection coefficient is proportional to the square of the refractive index difference. Therefore, the SNR, which scales reciprocally to the square root of the number of photons, will be attenuated by the refractive index difference, exactly negating the benefit of stronger phase change in reflection for a given laser power. However, if the scattering coefficient is enhanced by the turbulent tissue properties or by contrast enhancement agents (45, 46), the SNR might be significantly increased.

Another interesting possibility is to improve SNR using template-matching techniques based on full spatial and temporal correlations in the 4D spike-induced deformation movie. These could include machine-learning algorithms, along with spatial averaging over the region of interest (ROI) predicted by the 3D cell model from confocal microscopy or holographic tomography (47).

In our previous work (9), we estimated the phase change expected due to the refractive index variation because of the ion flux during the action potential to be less than 0.1 mrad—about an order of magnitude below the phase changes observed during an action potential in spiking HEK cells, and two to three times below the phase changes observed in neurons. In addition, the simultaneous positive and negative phase changes on the same cell cannot be explained by a unidirectional refractive index change, but they can be well explained by the cellular deformation.

Full-field imaging of cellular deformations at high temporal and spatial resolution enabled comparison of the experimental data with 3D modeling to elucidate the underlying mechanism of electromechanical coupling in cells. This comparison demonstrated that the voltage-dependent membrane tension-based model correctly describes the magnitude of the effect, the time course, and its spatial features. There are interesting parallels to the existing El Hady–Machta model for axon deformations (10), as both models involve an electromechanical coupling in the cell membrane based on the interactions of local charges and an accompanying liquid core–cortical shell mechanical model. The El Hady–Machta model assumes that when the transmembrane voltage changes, “the compressive forces on the membrane are altered leading to changes in shape and corresponding changes in capacitance” (ref. 10, p. 3), which leads to a quadratic voltage-to-force relationship and a N/m membrane tension change (10). However, multiple independent observations show the voltage-to-force relationship to be linear and measure a smaller N/m membrane tension change during the action potential (9, 15, 16, 18, 19). Thus, in this work, we favor voltage-dependent membrane tension changes due to lateral repulsion of ions in the Debye layers (15), which features a quasi-linear voltage-to-force relationship and tension predictions that match published measurements. More accurate measurements in the future might revisit this debate on the grounds that a quadratic relationship might be difficult to distinguish from a linear effect in a narrow range of voltage changes (100 mV). This could be determined by harmonic measurements, as in refs. 18 and 19, extended to higher frequencies and improved SNR to reveal any telltale second harmonic component of the deformations from an underlying quadratic effect.

Given the nonspherical shape of neurons in the brain (48), we expect deformations to be present, such that noninvasive label-free imaging of action potentials, especially in reflection geometry, may offer invaluable opportunities for real-time, high-bandwidth readout from large areas in the brain. Our observations of the spike-induced cellular deformations and validation of the underlying theory bring this goal closer to practical implementation.

Materials and Methods

Primary Neuronal Culture.

All experimental procedures involving animals were conducted under protocols approved by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care. Primary neuronal cultures were isolated from postnatal day 0 (P0) rat cortical tissues. The cortices were dissected, the meninges removed, and tissue was digested with 0.4 mg/mL papain (Worthington Biochemical Corporation) in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) (no. 14175-095; Gibco) at for 20 min. The digested tissue was then triturated, and the cell pellet was resuspended in Neurobasal-A medium (Gibco), supplemented with 2 mM GlutaMax (Gibco), NeuroCult SM1 Neuronal Supplement (1:50 dilution; Stemcell Technologies), and 5% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were plated on MEAs or the gridded imaging dishes with coverslip bottoms (-Dish 35 mm, high Grid-500; ibidi), precoated with poly-D-lysine (PDL) (0.1 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich). The next day the plating medium was replaced with serum-free neuronal culture medium (Neurobasal-A medium [Gibco], 2 mM GlutaMax [Gibco], NeuroCult SM1 Neuronal Supplement [1:50 dilution; Stemcell Technologies]). Primary neuronal cultures were kept in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at and maintained by half-volume culture media exchange every 3 to 4 d.

For optogenetic stimulation experiments cells were plated at a density of 500 to 750 cells/, transduced with pAAV-CaMKIIa-C1V1 (t/t)-TS-EYFP (22) (AAV9) at 5 to 7 d in vitro (DIV 5 to 7) (Addgene viral prep no. 35499-AAV9; http://www.addgene.org/35499/; RRID:Addgene_35499; plasmid was a gift from K.D.), and supplemented with fluorodeoxyuridine (FUDR) (Sigma-Aldrich) solution to control glial cell growth. For spontaneously spiking cultures, the cells were plated at a density of 1,200 to 2,000 cells/ on MEAs, precoated with Matrigel, in addition to PDL. QPI, electrical recordings (for MEAs), and live-cell confocal microscopy were performed on DIV 17 to 28.

Recording of the Spike-Induced Deformations.

Quantitative phase microscopy.

Quantitative phase microscopy based on common-path diffraction phase microscopy (20, 49) was adapted from our previous work (9, 29) (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Light from the superluminescent diode (SLD) (SLD830S-A20; Thorlabs) was collimated by a fiber-coupled collimator (F220FC-780; Thorlabs). Neurons on MEAs or on imaging dishes were imaged via a 10 objective (CFI Plan Fluor 10, numerical aperture (NA) 0.3, working distance (WD) 16.0 mm; Nikon), and the light beam recollimated by a 200-mm tube lens (Nikon) was projected through a transmission grating (46-074, 110 grooves/mm; Edmund Optics) and a subsequent 4-f system. The 0th diffraction order of the grating was filtered through a 150- pinhole mask on the Fourier plane, while the first order was passed through without filtering. The 4-f system consisted of a 50-mm lens (AF Nikkor 50-mm f/1.8D; Nikon) and a 250-mm biconvex lens (LB1889-B; Thorlabs). The camera sensor (Phantom v641; Vision Research) captured the resulting interferograms at a frame rate of 10 kHz and a resolution of up to 768 480 pixels. For optimal data transfer, resolution was reduced to 512 384 pixels in most datasets.

Extracellular electrical recording using MEA.

Action potentials were recorded extracellularly using a custom 61-channel MEA system built on a transparent substrate with indium tin oxide (ITO) leads (9). The recording electrodes were electrodeposited with platinum black prior to culturing the neurons on MEAs. The cell growth areas on MEAs were 2 in size. Recorded electrical signals were amplified with a gain of 840 and filtered with a 43- to 2,000-Hz bandpass filter. A data acquisition card (NI PCI-6110; National Instruments) sampled the signals at 20 kHz. To synchronize the QPI recording with the MEA system, an external clock signal from a function generator connected to the camera’s F-Sync input was repeatedly triggered from the MEA system every 100 ms. In addition, the ready signal from the camera, marking the start of an image sequence acquisition, was recorded by the MEA system to synchronize the electrical and optical recordings.

Optogenetic stimulation.

A fiber-coupled LED (M565F3; Thorlabs) with its center wavelength at 565 nm was used to deliver light stimulation to the neurons expressing C1V1 (t/t) opsins. Output of that fiber was coupled to a collimator (F260SMA-A; Thorlabs) and the beam aligned into the rear port of the microscope (TE2000-U; Nikon) was directed onto the sample via a dichroic mirror (FF585-Di01-2536; Semrock) (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The beam was focused onto a 300- spot on the sample plane via a 10 objective to cover every cell in the FOV with a power density of 5.5 mW/, which is comparable to the reported power density required for eliciting spikes at nearly 100% success rate during 5-Hz stimulation (22). The illuminated spot was coaligned with the FOV of the QPI, so that the neurons of interest could be stimulated optically. An optical bandpass filter (FF01-819/44-25; Semrock) was placed in the imaging path to further filter out the back-reflected green light from the QPI beam.

High-efficiency recording of the spike-induced deformation.

To record spike-induced deformations from spontaneously firing neurons, real-time spike detection was utilized to selectively record segments with bursts of action potentials, while neglecting other sparse segments which waste limited recording time and data storage (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The camera was set to record 5,000 pretrigger frames and 1 posttrigger frame at a frame rate of 10 kHz. Once the MEA system detected more than a predetermined number of spikes (usually 10) in a 500-ms window, a trigger was sent automatically to the camera to save the previously buffered 500 ms of interferograms from the camera’s random-access memory (RAM) to its nonvolatile memory (CineMag II 512 GB; Vision Research). For optogenetically stimulated neurons, higher-efficiency recording was implemented by capturing only the 5 to 9 ms following each 5-Hz stimulus, along with the preceding 1-ms segments, and saved directly to the computer hard disk (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Data Processing.

Spike sorting.

The extracellular electrical recording data were analyzed using custom software developed by Litke et al. (50). Spikes were first identified using a peak signal-to-noise threshold ratio of 3:1. The spikes on each electrode, along with the waveforms on the adjacent electrodes, were projected into a space of reduced dimensionality using principal component analysis (PCA) and then clustered to several neuron candidates by the expectation-maximization algorithm. We further checked the neuron candidates by the time difference for all pairs of spikes, to clean out the contaminated clusters that have many spike pairs occurring within 1.5 ms. Only the neurons exhibiting highly repeatable spike patterns were chosen for generating the spike-triggered average phase movie.

STA phase movie.

The phase differences between the first interferogram in each movie sequence and the subsequent frames were computed by the fast phase reconstruction algorithm for diffraction phase microscopy (51), with additional acceleration using a graphics processing unit (Tesla K40c; Nvidia). Global phase fluctuation in each frame was eliminated by subtracting the spatial average of the background, while highly noisy pixels were excluded from the background ROI.

The STA phase movie was generated by aligning the phase difference movies to their spike times and averaging them together. The slow lateral drifts between movies were corrected by monomodal image registration based on the QPI images of their first frames. To ensure optimal averaging efficiency, noisy phase movies were rejected to prevent unexpected events, such as moving particles or sudden vibrations, from affecting the STA results.

Photothermal artifact correction.

Photothermal artifact correction was applied to the optogenetically stimulated datasets. The phase artifact due to the photothermal effect from the LED stimulation has two unique features: 1) predictable time dynamics that match the finite-element modeling (FEM) based on the temperature dependence of the refractive index of water and 2) low spatial frequencies compared to the cell structure. Leveraging these features, the photothermal signal can be decoupled from the phase change of the spike-induced deformation. First, a 50 50-pixel spatial averaging filter was applied to the STA phase movie to generate a spatially smoothed phase movie. The heating ROI was extracted by thresholding the cross-correlation between the template predicted by the FEM and the phase change on each pixel of the smoothed phase movie (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). The measured heating curve was obtained by spatially averaging the detected heating ROI while excluding the spiking ROI mentioned below. This curve, unique to each dataset, was then used to fit the phase change due to the photothermal effect on each pixel in the smoothed phase movie by linear regression with a normal equation, while neglecting the sample points when the cells spike. The background heating fitted to each pixel was subtracted from the phase change on that pixel in the original STA phase movie (SI Appendix, Fig. S7).

Spiking ROI segmentation.

The distinct spatial and temporal clumping of the phase signal in pixels throughout the STA was used to enhance the detection and segmentation of spiking cells compared to the shot-noise–limited performance of single pixels. By referring to previous observations of the spiking signal and its relation to the mechanical deformation, we used a known template (Fig. 2B) to match-filter each pixel. The output of this correlation gave an indication of how likely the spiking signal occurred on this pixel throughout the duration of the STA, as well as when the spike occurred, but was insufficient to segment every spiking pixel from the noisy background. We consolidated this per-pixel information across the whole STA to clump nearby pixels that spike together into a single spiking cell. We then grew those regions to fill holes left by the noise, according to the absolute phase measurement that indicated the cell structure. The result was a 3D spatiotemporal mask that passed only those pixels of the STA that had been detected as spiking at a given location and time (Movie S2).

Confocal Image Acquisition.

Three-dimensional imaging was performed using a Zeiss LSM 880 inverted confocal microscope with Zeiss ZEN black software (Carl Zeiss). Imaging dishes with cultured cells were placed on the microscope stage inside a large incubator (Zeiss Incubator XL S1) kept at during imaging. Image planes were acquired through the total thickness of the cell using a Z stack, with upper and lower bounds defined below the coverslip and above the cell membrane. Stacks were acquired using a 63/1.4 NA oil immersion objective (Plan-Apochromat 63/1.4 Oil DIC M27; Carl Zeiss) with a acquisition area, a 447-nm z step, and a 930-nm pinhole, with N = 8 line averaging. Deconvolution on the acquired image stacks was performed using Zeiss ZEN blue software (Carl Zeiss), using the fast iterative method. For illustrating 3D cell shapes in Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S3, images were analyzed using Imaris software (Bitplane).

Reconstructing 3D Cell Shapes from Confocal Images.

The confocal image stacks were manually segmented in 3D Slicer (52) (http://www.slicer.org) and exported as meshes to Netfabb software (Autodesk) to be converted into parametric surfaces for import into FEM software (COMSOL). Semiautomated segmentation algorithms, such as region growing and volume dilation, were combined with user-generated seeds and editing to select the cell of interest, including its nucleus and processes as far out as could be distinguished. Smoothing and remeshing operations were performed before generating a smooth parametric surface as the best fit to the mesh.

Modeling the Voltage-Induced Cellular Deformation.

FEM was implemented to model the cellular deformation due to the change in voltage-dependent membrane tension, using COMSOL Multiphysics software (v5.4). Based on the cortical shell–liquid core model, we assumed a 100-nm-thick cortical shell wrapping around a hemispheroidal liquid core. The cortical shell was set to be a linear elastic material since the cellular deformation is minute. A Young’s modulus of 1 MPa was calculated from the previous reports using the power-law relation due to viscoelasticity (25, 32, 33). The liquid core was assumed to be an incompressible laminar flow with a nonslip boundary condition. The viscosity of the liquid core was set to 2.5 mPas. To simulate the spike-induced deformation, a voltage-dependent membrane tension of /m was applied to the surface of the cortical shell.

To compare the predicted deformations with the phase imaging results, 3D cell shapes were imported into COMSOL using the computer aided design (CAD) import module. Except for the cell geometries, other parameters were set to be the same as those in the hemispheroidal model. Modeled phase images of cells were extracted using a general projection operation through the axis, while an additional halo effect in the QPI and spatial blurring due to the limited optical resolution were applied to the forward modeling.

Data Availability.

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main text and SI Appendix. Example code and experimental data including the STA phase movies of neuronal deformations and their corresponding cellular morphology are available on Figshare (dataset: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11879334).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by NIH Grant U01 EY025501 and by the Stanford Neurosciences Institute. We thank Drs. A. Roorda, B.H. Park, R. Sabesan, and E.J. Chichilnisky for fruitful discussions and Dr. K. Mathieson for providing the MEAs, as well as R. Tien and C. Raja for helping with dissection of cortical tissues for neuron culture.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. T.O.S. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data deposition: Example code and experimental data including the STA phase movies of neuronal deformations and their corresponding cellular morphology are available on Figshare (dataset: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11879334).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1920039117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hill B., Schubert E., Nokes M., Michelson R., Laser interferometer measurement of changes in crayfish axon diameter concurrent with action potential. Science 196, 426–428 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwasa K., Tasaki I., Gibbons R.. Swelling of nerve fibers associated with action potentials. Science 210, 338–339 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tasaki I., Kusano K., Byrne P. M., Rapid mechanical and thermal changes in the garfish olfactory nerve associated with a propagated impulse. Biophys. J. 55, 1033–1040 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laporta A., Kleinfeld D., Interferometric detection of action potentials. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2012, ip068148 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akkin T., Landowne D., Sivaprakasam A., Optical coherence tomography phase measurement of transient changes in squid giant axons during activity. J. Membr. Biol. 231, 35–46 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tasaki I., Iwasa K., Rapid pressure changes and surface displacements in the squid giant axon associated with production of action potentials. Jpn. J. Physiol. 32, 69–81 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim G. H., Kosterin P., Obaid A. L., Salzberg B. M., A mechanical spike accompanies the action potential in mammalian nerve terminals. Biophys. J. 92, 3122–3129 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Y., et al. , Imaging action potential in single mammalian neurons by tracking the accompanying sub-nanometer mechanical motion. ACS Nano 12, 4186–4193 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ling T., et al. , Full-field interferometric imaging of propagating action potentials. Light Sci. Appl. 7, 107 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hady A. E., Machta B. B., Mechanical surface waves accompany action potential propagation. Nat. Commun. 6, 6697 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H., Garcia-Gonzalez D., Jérusalem A., Computational model of the mechanoelectrophysiological coupling in axons with application to neuromodulation. Phys. Rev. E 99, 032406 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrov A. G., Sachs F., Flexoelectricity and elasticity of asymmetric biomembranes. Phys. Rev. E 65, 021905 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heimburg T., Jackson A. D., On soliton propagation in biomembranes and nerves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 9790–9795 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mussel M., Schneider M. F., It sounds like an action potential: Unification of electrical, chemical and mechanical aspects of acoustic pulses in lipids. J. R. Soc. Interface 16, 20180743 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang P.-C., Keleshian A. M., Sachs F., Voltage-induced membrane movement. Nature 413, 428–432 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen T. D., et al. , Piezoelectric nanoribbons for monitoring cellular deformations. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 587–593 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brownell W. E., Qian F., Anvari B., Cell membrane tethers generate mechanical force in response to electrical stimulation. Biophys. J. 99, 845–852 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh S., et al. , Label-free imaging of membrane potential using membrane electromotility. Biophys. J. 103, 11–18 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y., Liu X., Wang S., Tao N., Plasmonic imaging of subcellular electromechanical deformation in mammalian cells. J. Biomed. Optic. 24, 1–7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhaduri B., et al. , Diffraction phase microscopy: Principles and applications in materials and life sciences. Adv. Optic Photon 6, 57–119 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyden E. S., Zhang F., Bamberg E., Nagel G., Deisseroth K., Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1263–1268 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yizhar O., et al. , Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature 477, 171–178 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer-Friedrich E., Hyman A. A., Jülicher F., Müller D. J., Helenius J., Quantification of surface tension and internal pressure generated by single mitotic cells. Sci. Rep. 4, 6213 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chugh P., et al. , Actin cortex architecture regulates cell surface tension. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 689–697 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang J. H., et al. , Noninvasive monitoring of single-cell mechanics by acoustic scattering. Nat. Methods 16, 263–269 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park Y., Depeursinge C., Popescu G., Quantitative phase imaging in biomedicine. Nat. Photon. 12, 578–589 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hosseini P., et al. , Pushing phase and amplitude sensitivity limits in interferometric microscopy. Opt. Lett. 41, 1656–1659 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hochbaum D. R., et al. , All-optical electrophysiology in mammalian neurons using engineered microbial rhodopsins. Nat. Methods 11, 825–833 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goetz G., et al. , Interferometric mapping of material properties using thermal perturbation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E2499–E2508 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plaksin M., Shapira E., Kimmel E., Shoham S., Thermal transients excite neurons through universal intramembrane mechanoelectrical effects. Phys. Rev. X 8, 011043 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierre S., Julie P., Membrane tension and cytoskeleton organization in cell motility. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 27, 273103 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer-Friedrich E., et al. , Rheology of the active cell cortex in mitosis. Biophys. J. 111, 589–600 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grevesse T., Dabiri B. E., Parker K. K., Gabriele S., Opposite rheological properties of neuronal microcompartments predict axonal vulnerability in brain injury. Sci. Rep. 5, 9475 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puchkov E. O., Intracellular viscosity: Methods of measurement and role in metabolism. Biochem. (Mosc.) Suppl. Ser. A Membr. Cell Biol. 7, 270–279 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balland M., et al. , Power laws in microrheology experiments on living cells: Comparative analysis and modeling. Phys. Rev. 74, 021911 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y., et al. , Modeling of the axon membrane skeleton structure and implications for its mechanical properties. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005407 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fillafer C., Mussel M., Muchowski J., Schneider M. F., Cell surface deformation during an action potential. Biophys. J. 114, 410–418 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ling T., et al. , Neuronal deformation data and cellular morphology data from ‘High-speed interferometric imaging reveals dynamics of neuronal deformation during the action potential.’ Figshare. 10.6084/m9.figshare.11879334. Deposited 4 March 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Nguyen T. H., et al. , Halo-free phase contrast microscopy. Sci. Rep. 7, 44034 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kandel M. E., Fanous M., Best-Popescu C., Popescu G., Real-time halo correction in phase contrast imaging. Biomed. Optic Express 9, 623–635 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scanziani M., Hausser M., Electrophysiology in the age of light. Nature 461, 930–939 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin M. Z., Schnitzer M. J., Genetically encoded indicators of neuronal activity. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1142–1153 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gong Y., et al. , High-speed recording of neural spikes in awake mice and flies with a fluorescent voltage sensor. Science 350, 1361–1366 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park B. H., et al. , Real-time fiber-based multi-functional spectral-domain optical coherence tomography at 1.3 m. Opt. Express 13, 3931–3944 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu G. J., et al. , Biomolecular contrast agents for optical coherence tomography. bioRxiv:10.1101/595157 (31 March 2019).

- 46.Liba O., Sorelle E. D., Sen D., Zerda A. de la, Contrast-enhanced optical coherence tomography with picomolar sensitivity for functional in vivo imaging. Sci. Rep. 6, 23337 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim D., et al. , Refractive index as an intrinsic imaging contrast for 3-d label-free live cell imaging. bioRxiv:106328 (15 November 2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Tønnesen J., Inavalli V. V. G. K., Nägerl U. V., Super-resolution imaging of the extracellular space in living brain tissue. Cell 172, 1108–1121.e15 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Popescu G., Ikeda T., Dasari R. R., Feld M. S., Diffraction phase microscopy for quantifying cell structure and dynamics. Optic. Lett. 31, 775–777 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Litke A. M., et al. , What does the eye tell the brain?: Development of a system for the large-scale recording of retinal output activity. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 51, 1434–1440 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pham H. V., Edwards C., Goddard L. L., Popescu G., Fast phase reconstruction in white light diffraction phase microscopy. Appl. Optic. 52, A97–A101 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fedorov A., et al. , 3D slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn. Reson. Imaging 30, 1323–1341 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main text and SI Appendix. Example code and experimental data including the STA phase movies of neuronal deformations and their corresponding cellular morphology are available on Figshare (dataset: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11879334).