Significance

Meiosis is essential for creating gametes required for sexual reproduction. Mistakes in female meiosis result in eggs containing the improper number of chromosomes. This phenomenon, termed aneuploidy, is strongly associated with recurrent pregnancy loss and failure of in vitro fertilization procedures. Despite these associations, quantitative studies that link embryo aneuploidy to underlying errors in female meiosis are lacking. Using human embryo aneuploidy data, we developed a mathematical model describing all possible aneuploidies that arise from meiotic errors. Our model revealed aspects of the human aneuploidy etiology, including an association between errors arising during meiosis I and meiosis II. Our study demonstrates the power of quantitative modeling approaches to link karyotypic patterns to their originating meiotic error mechanisms.

Keywords: aneuploidy, chromosome missegregation, meiosis, maternal age effect, mathematical modeling

Abstract

Aneuploidy is the leading contributor to pregnancy loss, congenital anomalies, and in vitro fertilization (IVF) failure in humans. Although most aneuploid conceptions are thought to originate from meiotic division errors in the female germline, quantitative studies that link the observed phenotypes to underlying error mechanisms are lacking. In this study, we developed a mathematical modeling framework to quantify the contribution of different mechanisms of erroneous chromosome segregation to the production of aneuploid eggs. Our model considers the probabilities of all possible chromosome gain/loss outcomes that arise from meiotic errors, such as nondisjunction (NDJ) in meiosis I and meiosis II, and premature separation of sister chromatids (PSSC) and reverse segregation (RS) in meiosis I. To understand the contributions of different meiotic errors, we fit our model to aneuploidy data from 11,157 blastocyst-stage embryos. Our best-fitting model captures several known features of female meiosis, for instance, the maternal age effect on PSSC. More importantly, our model reveals previously undescribed patterns, including an increased frequency of meiosis II errors among eggs affected by errors in meiosis I. This observation suggests that the occurrence of NDJ in meiosis II is associated with the ploidy status of an egg. We further demonstrate that the model can be used to identify IVF patients who produce an extreme number of aneuploid embryos. The dynamic nature of our mathematical model makes it a powerful tool both for understanding the relative contributions of mechanisms of chromosome missegregation in human female meiosis and for predicting the outcomes of assisted reproduction.

Pregnancy loss is extremely common in humans. Nearly 20% of clinically recognized pregnancies result in miscarriage, and many more unrecognized pregnancies end earlier in development (1). A leading cause of early miscarriage is aneuploidy—defined by the possession of an abnormal number of chromosomes (2, 3). With the advent of assisted reproductive technologies, it has become clear that aneuploidy is the primary cause of in vitro fertilization (IVF) failure (4). The vast majority of embryonic aneuploidies trace their origins to errors in female meiosis, which increase in frequency with maternal age (2, 3, 5, 6). In contrast, paternal meiotic aneuploidies occur at low rates, as reported in many studies (2, 7–10), including a recent large single-cell study of human sperm (11). Because the average age at conception is increasing in developed countries (12–14), it is crucial to understand the mechanisms contributing to aneuploidy in female meiosis. Such basic knowledge is required to pave the way for future diagnostic and therapeutic innovations to improve human fertility.

Data obtained from preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) provide unprecedented resolution regarding the incidence and characteristics of chromosome abnormalities during preimplantation embryo development. PGT-A involves genomic profiling of DNA extracted from either single-cell biopsies of IVF embryos at the cleavage stage (day 3) or multicell trophectoderm biopsies at the blastocyst stage (days 5 to 6). Although many previous studies have reported frequencies of various chromosome abnormalities observed in PGT-A data (e.g., refs. 10 and 15), few studies have applied quantitative approaches to associate observed aneuploidies with their underlying error mechanisms, such as premature separation of sister chromatids in meiosis I (MI-PSSC), nondisjunction in meiosis I (MI-NDJ), reverse segregation in meiosis I (RS), and nondisjunction in meiosis II (MII-NDJ). Inferences of mechanism-specific error rates are challenging, because although they occur at different frequencies, the chromosome gains and losses produced by different mechanisms can result in identical karyotypes.

Mathematical modeling can help overcome this limitation. For example, previous studies used mathematical modeling to gain insights into the mechanisms of chromosome missegregation in yeast (16, 17). In these studies, the authors assumed that any chromosome missegregation event is random and follows a binomial distribution. Although useful for learning the overall probability of a chromosome to missegregate, this approach cannot further disentangle the error source (e.g., MI or MII) and type (e.g., NDJ, PSSC, or RS). Here, we took a different approach. By considering major mechanisms of chromosome missegregation during human oocyte meiotic maturation (MI-PSSC, MI-NDJ, RS, and MII-NDJ), we enumerated all possible outcomes of female meiosis. Each meiotic outcome was then transformed into an overall probability with model parameters directly describing the relative contributions of MI and MII errors. We used the observed abnormalities from human PGT-A data to investigate chromosome missegregation frequencies that lead to aneuploid conceptions. Together, our model revealed unexpected correlation between MI and MII errors and biological insights into the genesis of human female meiosis aneuploidy.

Model

Model Development.

We developed a mathematical framework to describe female meiosis, linking aneuploidy outcomes to their underlying error mechanisms. When concluded without errors, female meiosis results in the formation of a mature euploid zygote. When errors occur during MI, chromosomes missegregate either due to nondisjunction of the homologous pair of chromosomes (MI-NDJ) or due to MI-PSSC. Errors may also arise during MII due to MII-NDJ. We modeled the MI and MII errors with the following assumptions: 1) at most, one chromosomal error occurs per cell division; 2) all chromosomes were considered to have equal probabilities of missegregation, rather than chromosome-specific probabilities (in Discussion, we also provide a section where we relax this assumption); and 3) chromosomes or chromatids are equally likely to segregate to the MII egg and the first polar body, PB1, during MI or the fertilized zygote and the secondary polar body, PB2, in MII.

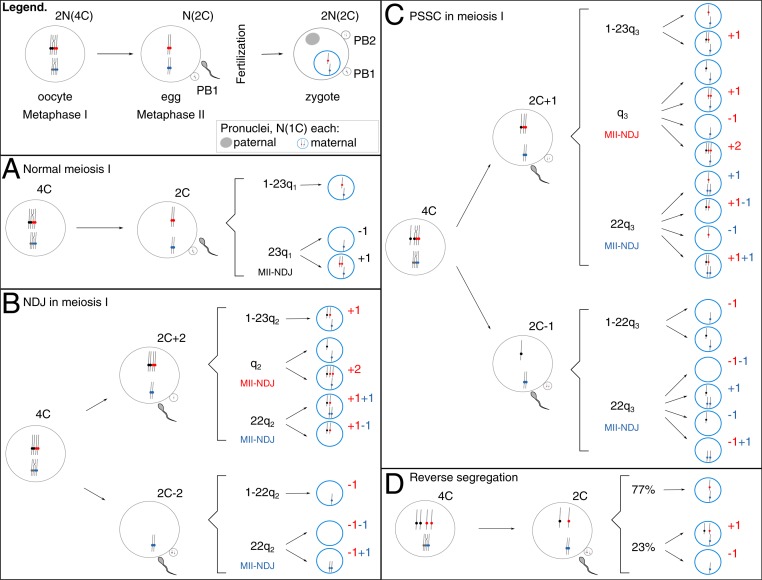

Because reverse segregation, where sister chromatids segregate in MI and homologs segregate in MII, was recently described as an additional prominent error mechanism in aging oocytes (18, 19), we also investigated the effects of its inclusion on overall model performance. All possible chromosome segregation outcomes of the model are depicted in Fig. 1 and listed in Table 1, along with their underlying mechanisms and derived probabilities. Here, we use N to describe a full haploid human chromosome set and C the number of chromatids (Fig. 1, “Legend”). Because the completion of MII does not occur until after fertilization, a euploid unfertilized egg is N(2C). For equations in Table 1, we used the parameter d to express the overall probability of a single chromosome MI-NDJ missegregation event and the parameter p to describe a single chromosome MI-PSSC missegregation event. When fertilized, the metaphase II-arrested egg will complete MII. In MII, chromosomes can erroneously segregate due to an MII-NDJ event. We indicated a single chromosome MII-NDJ with parameters qi, i = {1,2,3} in Table 1, respectively. For a euploid egg, i.e., carrying an expected number of chromosomes N(2C), the probability of an MII-NDJ event was modeled with q1. Considering that each of the 23 chromosomes in the normal egg has a chance to be affected, we arrived at an overall probability of MII error equal to 23q1 (Fig. 1A). Following an MI error—either MI-NDJ or MI-PSSC—the probability of the same chromosome being affected again during MII due to an MII-NDJ event was modeled with q2 and q3, respectively (Fig. 1 B and C, indicated in red). Analogous to the euploid egg, the probability of a different chromosome being affected by MII-NDJ compared with the one affected during MI was modeled with the parameters 22q2 and 22q3, respectively (Fig. 1 B and C, indicated in blue). Finally, we used the parameter r to express the overall probability of an RS event affecting a single chromosome in MI. During MII, the homologous chromatids can either segregate to the mature egg and PB2 (with probability s) or cosegregate with probability 1 − s and remain in one of the MII products (either the mature egg and give rise to trisomy or PB2 and give rise to monosomy; Fig. 1D). A previous report suggested that s = 77% (18). This value, however, is from a limited number of IVF patients (six patients; on average, 37/38 y old). We discuss its impact on the model estimates below.

Fig. 1.

Graphical representation of the model. (Legend) C describes the number of chromatids with respect to a haploid genome (N). Shortly before ovulation, a dictyate stage oocyte [2N(4C)] will complete MI, giving rise to a euploid egg [N(2C)] and the first polar body, PB1 [also N(2C)]. When fertilized, the egg will complete second stage of meiosis, MII, giving rise to a euploid zygote [2N(2C)] and a secondary polar body, PB2 [N(1C)]. Parental nuclei are separate entities at this stage [N(1C) each]. Possible outcomes of meiosis are enumerated for either error-free MI (A) or MI errors NDJ (B), PSSC (C), or RS (D). For zygotic maternal pronuclei (blue circles), only a deviation from normal haploid status N(1C) is noted. (A) Following error-free MI, a euploid egg [N(2C)] is fertilized and gives rise to either a euploid zygote (with probability 1 − 23q1, where q1 stands for the probability of an MII-NDJ error on a single chromosome; Table 1) or to an aneuploid zygote (with a probability 23q1; Table 1). (B) There is a probability d of an MI-NDJ error. An affected dictyate oocyte will then give rise to an egg that either carries an extra chromosome copy (i.e., two more chromatids, 2C + 2) or lacks it entirely (2C − 2). (C) There is a probability p of an MI-PSSC error in MI. An affected dictyate oocyte will then give rise to an egg that either carries an extra chromatid (2C + 1) or lacks one (2C − 1). (B and C) In MII, the sister chromatids can fail to separate due to NDJ. MII-NDJ can either affect that same chromosome (depicted in red, with a probability q2 in B and q3 in C) or a different one (depicted in blue, with a probability 22q2 in B and 22q3 in C). (D) There is a probability r of an RS error in MI, but the affected dictyate oocyte will give rise to an egg that carries normal chromosome content (2C). Following MII, the zygote will either carry normal chromosome number (77% of the times) or not (23% of the times) (18). The pairs of homologous chromosomes are colored in black/red and gray/blue. The dots represent centromeres. Complex events affecting multiple chromosomes during meiosis occur with an overall probability c, which is included in model equations in Table 1.

Table 1.

Possible meiosis outcomes

| Meiosis outcome | Error source | Overall probability |

| Euploid conception | Normal | (1 − d − p − r − c) (1 − 23q1) |

| MI-NDJ + MII-NDJ | 0.25 d q2 | |

| MI-PSSC + MII-normal | 0.25 p (1 − 23q3) | |

| MI-PSSC + MII-normal | 0.25 p (1 − 22q3) | |

| MI-PSSC + MII-NDJ | 0.125 p q3 | |

| MI-RS + MII-homologs split | r 0.77 | |

| Single monosomy | MI-Normal + MII-NDJ | 0.5 (1 − d − p − r − c) 23q1 |

| MI-NDJ + MII-normal | 0.5 d (1 − 22q2) | |

| MI-PSSC + MII-NDJ | 0.125 p q3 | |

| MI-PSSC + MII-NDJ | 0.125 p 22q3 | |

| MI-PSSC + MII-NDJ | 0.125 p 22q3 | |

| MI-PSSC + MII-normal | 0.25 p (1 − 22q3) | |

| MI-RS + MII-cosegregation | 0.5 r 0.23 | |

| Single trisomy (due to MII error) | MI-Normal + MII-NDJ | 0.5 (1 − d − p − r − c) 23q1 |

| MI-PSSC + MII-NDJ | 0.125 p q3 | |

| MI-PSSC + MII-NDJ | 0.125 p 22q3 | |

| MI-PSSC + MII-NDJ | 0.125 p 22q3 | |

| MI-RS + MII-cosegregation | 0.5 r 0.23 | |

| Single trisomy (due to MI error only) | MI-NDJ + MII-normal | 0.5 d (1 − 23q2) |

| MI-PSSC + MII-normal | 0.25 p (1 − 23q3) | |

| Two trisomic chromosomes | MI-NDJ + MII-NDJ | 0.25 d 22q2 |

| MI-PSSC + MII-NDJ | 0.125 p 22q3 | |

| Trisomy + monosomy | MI-NDJ + MII-NDJ | 0.25 d 22q2 |

| MI-NDJ + MII-NDJ | 0.25 d 22q2 | |

| MI-PSSC + MII-NDJ | 0.125 p 22q3 | |

| MI-PSSC + MII-NDJ | 0.125 p 22q3 | |

| Two monosomic chromosomes | MI-NDJ + MII-NDJ | 0.25 d 22q2 |

| MI-PSSC + MII-NDJ | 0.125 p 22q3 | |

| Unbalanced tetrasomy, 3:1 | MI-NDJ + MII-NDJ | 0.25 d q2 |

| MI-PSSC + MII-NDJ | 0.125 p q3 |

Embryo types are shown with their corresponding probabilities of occurrence derived based on model structure depicted in Fig. 1. The parameters are defined in the model section of the main text.

Variations of the Model.

As introduced in Model Development, an MII-NDJ error of a single chromosome was expressed with parameters (q1, q2, q3), depending on the MI outcome, i.e., MI-Normal, MI-NDJ, or MI-PSSC (Fig. 1 A–C, respectively). Three different versions of the model were considered: Model 1: (q, q, q); Model 2: (q, q*, q*); Model 3: (q, q*, q#).

Briefly, in Model 1, we hypothesized that all MII-NDJ events are equally likely, regardless of the fidelity of the previous MI division. In this model, the parameters q1, q2, q3 were assumed equal to a single parameter q. In Model 2, we assumed that q1 = q and q2, q3 = q*, reflecting the hypothesis that the probability of MII-NDJ in a euploid egg (2C) is different from that in an aneuploid egg (2C ± 1 or 2C ± 2). In Model 3, we assumed all qi, i = {1,2,3} are different, following the hypothesis that the type of MI error also influences the probability of MII-NDJ. As such, in Model 3, we set q1 = q, q2 = q*, and q3 = q#. We also investigated the impact of RS on the Model 2 performance.

Results

Data Description.

To parameterize the models, we used previously published PGT-A data from biopsies of 18,387 day-5 IVF embryos (10). Although day-5 data will include some errors of mitotic origin, previous work indicated that many mosaic embryos arrest before day 5, making day-5 data more suitable for investigating meiotic errors compared with day-3 PGT-A data (10, 20, 21). After removing embryos carrying putative mitotic or paternally contributed errors (Methods), we obtained 11,157 day-5 embryos from 2,920 patients with either normal karyotypes or aneuploidies affecting maternal chromosomes (Table 2). Putative paternal errors were excluded to provide accurate estimates for female chromosomal numerical abnormalities. Of note, paternal meiotic errors were extremely rare in the dataset (<1% of all embryos affected; Table 2; also noted in ref. 10), which is in line with other reports of meiotic errors among healthy and infertile males (2, 7–9, 11). The patients contributing data to this study underwent IVF treatment for various reasons (e.g., previous IVF failure, male factor, etc; SI Appendix, Fig. S1). With the exception of translocation carrier status (a small fraction of patients), only modest associations between the aneuploidy rate and the clinical history were reported (10), supporting that our modeling results are not biased toward a particular clinical history.

Table 2.

Overview of embryos karyotype categories

| Case reported | No. of embryos | Proportion |

| Embryos in database | 18,387 | . |

| Unknown karyotype | 3,664 | . |

| Suspect duplicates | 19 | . |

| Unknown maternal age | 1,848 | . |

| Errors affecting paternal chromosomes | 1,443 | . |

| Segmental duplications | 256 | . |

| Embryos for analysis | 11,157 | 1 |

| No. of patients | 2,920 | . |

| Embryos with normal karyotype (46,XX or 46,XY) | 7,221 | 0.647 |

| Embryos with one error | 2,537 | 0.227 |

| Single trisomy | 1,273 | 0.114 |

| Single monosomy | 1,264 | 0.113 |

| Embryos with two errors | 768 | 0.069 |

| Double monosomy | 217 | 0.019 |

| Trisomy and monosomy | 344 | 0.031 |

| Double trisomy | 207 | 0.019 |

| Embryos with complex aneuploidies (>2 errors) | 631 | 0.057 |

PGT-A day-5 data and the proportion of each embryo type are shown. The nine underlined entries were used in the model selection step. Period (.) indicates not applicable.

For age-specific inferences of model parameters, we further split the embryos by age of the mother (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). Due to small sample sizes in certain age categories, patients with maternal ages 20 to 26 y were considered as one age category and similarly so were patients aged 27 to 28 and 44 to 48 y. As previously reported, proportions of embryos with single, double, and complex aneuploidies (i.e., those with three or more aneuploid chromosomes) increased with maternal age (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A, red, yellow, and green bars, respectively), while the proportion of euploid embryos consistently declined (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A, blue bars). The incidence of single trisomies and single monosomies were similar across all chromosomes (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) and maternal ages (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B), which supports the argument that both are likely to derive from the same mechanism and justifies their inclusion in our modeling framework.

Aneuploid Eggs Are More Prone to MII-NDJ Compared to Euploid Eggs.

To select the model that best explains the PGT-A data, we used the day-5 counts of aneuploid embryos (Table 2, underlined nine entries). The embryo categories used for model selection were 1) proportions of euploid embryos, 2) embryos with a single error (further split into single monosomies or single trisomies), 3) embryos with exactly two errors (further subcategorized into double trisomies, double monosomies, or trisomy and monosomy), and 4) complex aneuploidies (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C).

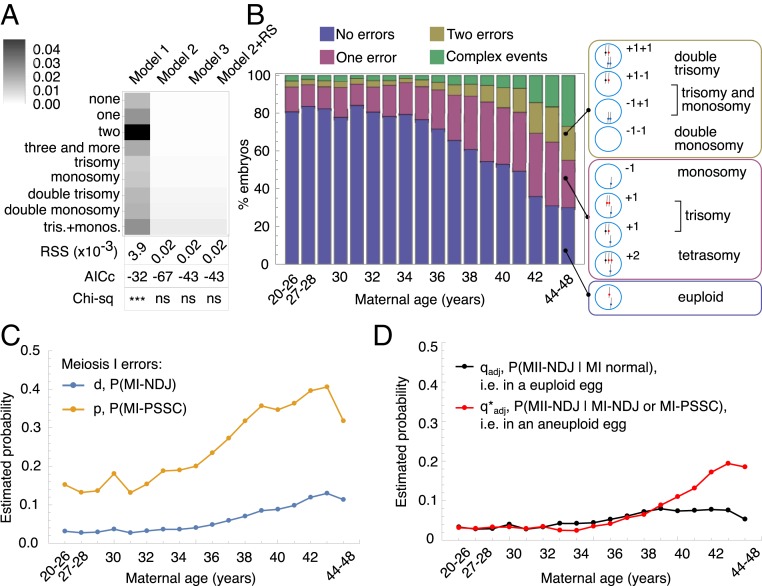

All models described in Variations of the Model above had three error rates in common: MI-NDJ (d), MI-PSSC (p), and complex errors (c). Model 1 had a single MII-NDJ error rate (q), whereas Model 2 had two MII-NDJ rates (q and q*) and Model 3 had three MII-NDJ rates (q, q*, and q#). We also present the results of Model 2 with RS incorporated where one more parameter for RS was estimated (r). We estimated the parameters of the models by minimizing the sum of squared residuals between the model simulations and the observed counts for nine embryo categories (RSSnine; Methods). Moreover, because many previous studies showed that MI-PSSC (typically not distinguished from RS) is the predominant source of MI error (21–28), we specified that d < p, meaning that MI-NDJ events are less likely to occur compared with MI-PSSC. Among the tested models, Model 1 provided the worst fit to the observed data (Fig. 2A; RSSnine = 3.9 × 10−3), where none of the nine categories could be explained well, especially for double-error categories (Fig. 2A, darkest boxes). Model 2, Model 3, and the incorporation of RS into Model 2 resulted in similar fits to the data (Fig. 2A; RSSnine = 2 × 10−5), and the simulated data under the three models did not significantly deviate from the observed counts (P = 0.83 for all three models, χ2 goodness-of-fit test; Methods). Compared with Model 2, incorporation of RS and Model 3 both require an additional parameter (r and q#, respectively). We used corrected Akaike information criteria (AICc) to compare model fits while accounting for the number of model parameters (ref. 29 and Methods). Because Model 2 had the lowest AICc value (AICc = −67), we selected Model 2 for the data analysis presented in this work. As discussed below in the section describing the relationship between MI-PSSC ad RS, the parameter p is likely to reflect a combination of MI-PSSC and RS processes and should be interpreted as a combined rate throughout the text.

Fig. 2.

Model estimates. (A) Model selection. Rows represent different karyotypes in the dataset (from euploid embryos to embryos with one trisomic and one monosomic chromosome, with frequencies provided in Table 2), and columns indicate the different models. For each karyotype, relative differences between model simulation and data were color-coded on a gray scale, where white represents a perfect fit of the model to the data, and black means that the model returned a value different from the observation (see color legend for precise values). AICc and χ2 below the array plot represent the AICc and the significance obtained from χ2 goodness-of-fit test performed on each model estimates compared with observations. ns, not significant; ***P < 2.2 × 10−16. (B) Four major karyotype categories simulated with Model 2. “No error” category (blue bars) represents the count for euploid embryos. “One error” category (red bars) represents single-monosomy or single-trisomy embryos. “Two errors” category (yellow bars) represents embryos with two aneuploid chromosomes. “Complex events” category (green bars) accounts for the complex error karyotypes. For reference, all possible meiosis outcomes are shown to the right and indicate which meiosis outcome was used to explain the category plotted on the left. (C and D) Estimated error rates for Model 2 in each age category. The MI-PSSC error rate (p) and MI-NDJ error rate (d) are shown in yellow and blue, respectively (C). The adjusted MII-NDJ error rate in a euploid egg (q) or in an aneuploid egg (q*) are shown in black and red, respectively (D). Adjusted MII rates are used to account for the MI outcome (Methods).

Model 2 suggests that the probability of an error in MII is associated with the aneuploidy status of an egg following MI. Specifically, in Model 2, the average probability of MII-NDJ of a single chromosome in a euploid egg was set to q (Fig. 1A), while the average probability of MII-NDJ of a single chromosome in an aneuploid egg was set to q* (Fig. 1 B and C). Note that q* describes an average rate for any chromosome, regardless of which chromosome was affected in MI. In this model, the inferred values of q (0.056 after adjustment; Methods and SI Appendix, Table S1) and q* (0.121 after adjustment) suggested that the probability of a chromosome missegregation event in MII is higher in an aneuploid egg compared with a euploid egg (∼2.2-fold enrichment in aneuploidy in MI aneuploid eggs; SI Appendix, Table S1). This result is intriguing, because it implies that the probability of MII-NDJ is strongly associated with the outcome of MI.

Inference of Age-Specific Error Rates.

To capture the dynamic nature of meiotic errors, we performed age-specific parameter estimation for Model 2. Because single trisomy, single monosomy, double trisomy, double monosomy, and combined trisomy and monosomy counts exhibited erratic behavior across ages (which we attribute to small sample sizes within age bins; SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B–F, shown in red), we only used the four major outcome categories (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A) to minimize RSSfour in each age group.

Overall, using the estimated parameters (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Methods), Model 2 accurately approximated the four major outcome categories (compare Fig. 2B with SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). For the remaining five outcome categories, the model simulations showed only modest deviations from the observations across examined maternal ages (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B–F, shown in black). Our age-specific estimates of model parameters demonstrated that all meiotic errors increased with maternal age, although to differing extents. Among all errors, MI-PSSC was the most dramatically affected by maternal age, with an inflection point around 35 y; the average error rate increased by a proportion of 0.007/y in women younger than 35 y but 0.018/y in women older than 35 y (Fig. 2C, yellow). In addition, we found that the maternal age effect on MII error was stronger in an aneuploid egg than in a euploid egg (Fig. 2D, red vs. black lines, respectively). MII-NDJ in euploid eggs started to increase in women older than 35 y and reached a plateau around the age of 38, with an average increase rate of 0.1/y in younger women (<35 y) vs. 8 × 10−4/y in older women (>35 y). On the other hand, although the maternal age effect on MII-NDJ in aneuploid eggs was delayed (inflection point around 38 y), the average rate of increase was much greater (−3.3 × 10−4/y in younger women vs. 2.8 × 10−3/y in older women; Fig. 2D). This association suggests that MII-NDJ is differentially affected by maternal age, depending on whether it occurs in a euploid or in an aneuploid egg.

Identification of Patients with Extreme Aneuploidy Rates.

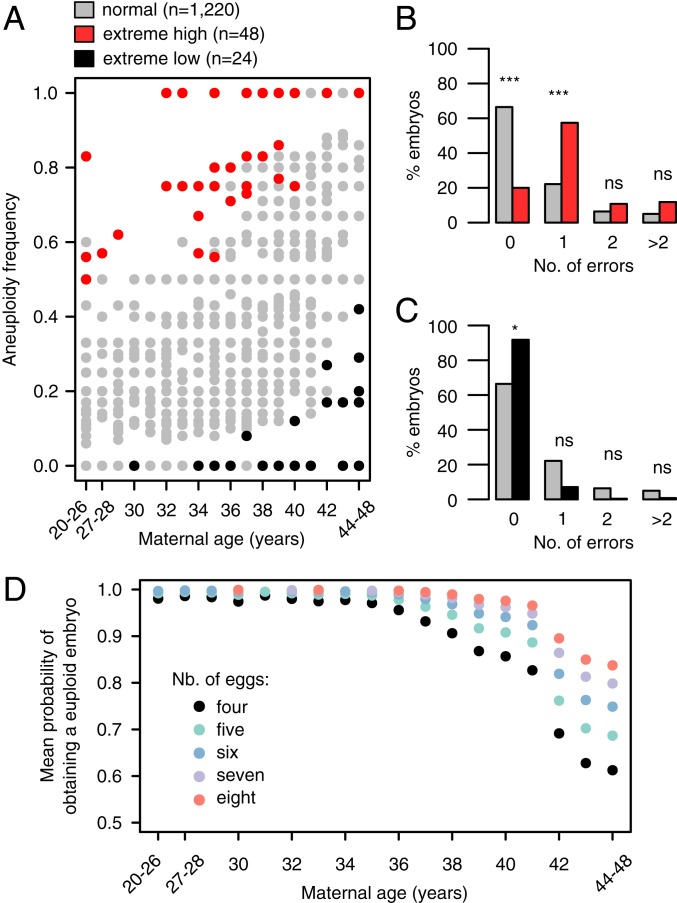

Aneuploidy is a major contributor to IVF failure, and many studies are focused on identifying genetic factors contributing to egg quality. Proper sampling of patients is crucial for these genomic studies. We hypothesized that this modeling approach can be applied to select individuals with extreme aneuploidy rates for downstream sequencing or genome-wide association studies. To demonstrate this application, we simulated individual patient aneuploidy rates using the estimated parameter values in SI Appendix, Table S2 (Methods). For each age category and the number of embryos evaluated, we performed 10,000 simulations of the model to generate empirical null distributions of the corresponding aneuploidy rates. We then categorized an individual as having an extreme high/low aneuploidy rate whenever she produced a proportion of aneuploid embryos that fell within the 5% right/left tail of the empirical null distribution, respectively. Using this definition, we could identify phenotypically extreme individuals in the observed data on both ends of the age spectrum (Fig. 3). Among the 1,292 patients with data from at least four day-5 embryo biopsies, we identified 48 individuals with extreme high aneuploidy rates (Fig. 3, red dots). Similarly, we identified 24 individuals on the other extreme, with lower than expected aneuploidy rates given model simulations (Fig. 3, black dots).

Fig. 3.

Model simulations detect individuals with extreme aneuploidy rates and can be used to calculate overall probability of euploid conception. (A) The dots represent 1,292 patients who had a minimum of 4 embryos evaluated for chromosomal abnormalities on day 5. Red and black dots highlight the patients with aneuploidy rates with probabilities less than 0.05, based on 10,000 model simulations of each patient, considering her age and the number of tested embryos (186 unique combinations of age and number of embryos in total). (B and C) Major error categories among normal individuals (gray bars collapsed from gray dots in A; n = 1,220) and individuals with extreme-high aneuploidy rates (red bars, collapsed from red dots in A; n = 48) (B) or the individuals with extreme-low aneuploidy rates (black bars collapsed from black dots in A; n = 24) (C). (D) Mean probability of obtaining a euploid embryo in a single IVF cycle, stratified by patient’s age and the number of available eggs. Reported are raw P values from the proportion test. ns, not significant; *P < 0.05; ***P < 1 × 10−8.

We then compared the types of errors observed in the extreme patients with the errors affecting embryos from the rest of the patients (Fig. 3, red/black vs. gray dots). Interestingly, single-chromosome aneuploidy was the most enriched error type among patients with extreme high aneuploidy rates, as opposed to double or complex error events (Fig. 3B). Extreme patients from the low aneuploidy rate group did not show any strong differences in the four categories examined (Fig. 3C).

Older Patients Are Much More Likely to Benefit from Multiple Rounds of IVF.

As proof of principle of clinical utility of our model, we used the derived probabilities of aneuploidy rates to determine the mean probability of having a euploid conception, given the age of the patient and number of eggs retrieved (Fig. 3D and see Methods for details). In fact, since recently, there is a suggestion that controlled ovarian stimulation procedures should be tailored to each patient to ensure that at least one of the collected eggs will develop into a euploid embryo after fertilization (30). It is known that in addition to high risk of aneuploidy, patients of advanced maternal age (e.g., over 40 y) are also limited by the number of eggs that can be retrieved during a single IVF cycle (31). From the model simulations (Fig. 3D), we learned that, for instance, for a 42-y-old patient with an expected retrieval yield of four eggs per cycle, that patient could increase the average probability of obtaining a euploid embryo from ∼70 to ∼90% when doubling the retrieval rate (eight eggs retrieved instead of just four eggs). Thus, our model simulations suggest that increasing the retrieval rate (or, alternatively, undergoing multiple rounds of egg retrieval) may be particularly useful for patients of advanced maternal age, as compared with the younger cohort (less than 35 y old) (Fig. 3D).

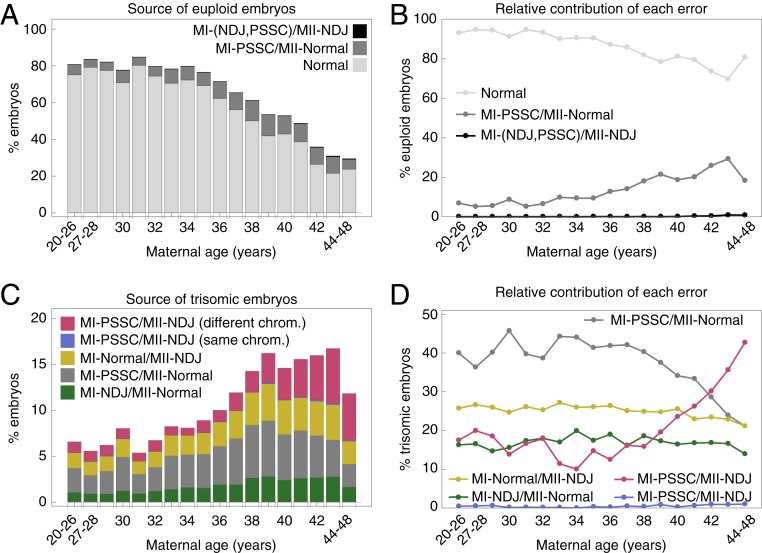

Source of the Abnormal Karyotypes.

To assess the underlying cause of various chromosome abnormalities, we simulated 1,000 patients with 10 oocytes for each age category and recorded which errors resulted in either euploid or aneuploid embryos. Our simulations revealed that MI-PSSC (combined with RS) events contributed to a substantial proportion of euploid embryos, particularly in patients of advanced maternal age (≥35 y) (Fig. 4A). This result was not intuitive, because MI-PSSC is the most frequent error to occur during female meiosis and is often associated with aneuploid embryo production. On average, about 18% of the euploid embryos in patients of advanced maternal age resulted from an MI-PSSC event followed by an error-free MII (Fig. 4 A and B, dark gray), compared with an average of 7% in younger patients (<35 y) (Fig. 4 A and B, dark gray). This modeling result highlights the contribution of MI-PSSC to both aneuploid and euploid embryos. Additional MII-NDJ events contributed little to euploid zygote formation across the entire age span (Fig. 4 A and B, black).

Fig. 4.

Karyotypes and underlying error mechanisms stratified by maternal age categories. (A) Euploid embryo source. Light gray bars represent euploid embryos obtained from normal meiosis (MI-Normal/MII-Normal). Dark gray bars indicate euploid embryos as a result of MI-PSSC/MII-Normal. Black bars represent a sum of euploid embryos from MI-NDJ/MII-NDJ and MI-PSCC/MII-NDJ. (B) Relative contribution of errors in A to euploid embryos. (C) Single-trisomy embryo source. Green and gray bars represent trisomic embryos as an outcome of MI-NDJ/MII-Normal and MI-PSSC/MII-Normal, respectively. Yellow bars represent outcomes of MI-Normal/MII-NDJ. Blue and red bars represent outcomes of MI-PSSC/MII-NDJ on the same chromosome (depicted in red in Fig. 1) and a different one (depicted in blue in Fig. 1), respectively. (D) Relative contribution of errors in C to trisomic embryos. MI-NDJ/MII-NDJ outcomes can give rise to pronuclei with “+2” DNA content. Upon simulation of the model, these outcomes occurred at a frequency of <1% across the entire age span and are thus omitted from the figure for clarity.

When studying the source of trisomic embryos, we observed that the relative contributions of different error types varied by age groups. MI-PSSC errors followed by error-free MII contributed the most to trisomic embryos in patients younger than 41 y of age (Fig. 4 C and D, gray). In patients older than 41 y old, however, MI-PSSC followed by MII-NDJ on a different chromosome became the primary source of trisomic embryos (Fig. 4D, red line). Contribution of MII-NDJ to trisomic embryos was unaffected by age in euploid eggs (Fig. 4D, yellow line) or when the same chromosome was affected in both MI and MII (Fig. 4D, blue line).

Discussion

Faithful chromosome segregation during meiosis is essential to survival in sexually reproducing species. However, female meiosis in humans is remarkably error-prone, leading to frequent miscarriages (2, 3) and failures of IVF (4). Using a mathematical framework, we investigated the contributions of various female meiotic errors to aneuploidy. We demonstrated that the approach can effectively quantify the rates of these error mechanisms, their dependence on one another, and the extent to which they are associated with maternal age.

Association between MI and MII Errors.

One intriguing result of the modeling is that the probability of MII-NDJ error is strongly associated with the MI outcome, i.e., chromosomes are far more likely to missegregate in an aneuploid egg than in a euploid one (see estimates in SI Appendix, Table S2). Two non-mutually exclusive hypotheses emerge from this observation. First, MI errors alter the cellular environment in the egg, which in turn increases the risk of MII errors. Second, the genetic background or environmental factors predispose an individual to both MI and MII errors, and therefore the MI and MII error rates are correlated. A possible explanation for the latter is the decrease in sister chromatid cohesion that is associated with maternal age (32–36). Studies in animal or cellular systems that can control the genetic and environmental background or monitor the cellular environment will help to disentangle and test these hypotheses.

MI-PSSC and RS Error Rates Are Indistinguishable in Our Dataset.

Recent reports indicate that RS is a prominent mechanism contributing to aneuploidy in human eggs (6, 37, 38). However, our data do not possess the resolution to effectively disentangle this mechanism from MI-PSSC errors. Specifically, the PGT-A data we used were not based on polar-body biopsies, making the outcomes of RS indistinguishable from the outcomes produced by other errors. In contrast, MI-PSSC and MI-NDJ are crucial to generate embryos with errors involving two chromosomes. We also know that MI-PSSC is more prevalent than MI-NDJ, which helps to further differentiate the two mechanisms. With this in mind, we investigated the impact of RS on model estimates and present the results in SI Appendix, Fig. S4. Importantly, we learned that the degree to which meiotic drive may be acting upon RS (18) significantly affects the inferred ratios of MI-PSSC and RS (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Thus, more data with polar body information across maternal ages are necessary to evaluate the MI-PSSC/RS relationship. Although MI-PSSC prevalence decreased when RS was included, the other errors remained largely unaffected (compare Fig. 2 C and D with SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Thus, we emphasize that any discussion of MI-PSSC in the current Model 2 should be interpreted as a combination of MI-PSSC/RS. The two errors could be further disentangled when more data become available in the future.

Dynamics of Meiotic Errors.

The PGT-A data were collected from individuals ranging from 20 to 48 y old, which allowed us to use our modeling framework to explore how female meiotic errors change with age. Both MI and MII errors could suffer from age-related effects (21, 39), and our modeling results further support this age-related association. As anticipated, our results suggest that MI-PSSC is strongly affected by maternal age (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Table S2). Also, our results indicate that in a euploid egg, the probability of a chromosome to missegregate in MII is low and is only mildly affected by maternal age. In contrast, in an aneuploid egg, probability of a chromosome to missegregate in MII increases more drastically with maternal age (Fig. 2D; see raw values in SI Appendix, Table S2). Without this modeling framework, it would be challenging to disentangle this dynamic nature of MII-NDJ errors and their association with MI outcome and maternal age. As described later in Discussion, despite our filtering, our data likely include some cases of mitotic error. However, previous analysis of this dataset suggested that mitotic errors are not associated with maternal age (10). Similarly, trisomies with signatures of mitotic errors are not strongly associated with maternal age, whereas trisomies comprising three unmatched haplotypes—a signature of meiotic error—exhibit strong associations with maternal age (40). We thus conclude that the maternal-age associations that we observe very likely trace to errors of meiotic origin.

Stochastic Simulation of Meiosis Outcomes.

Using the inferred parameter values from a clinical dataset, we showed that the model can be used to perform simulations of meiotic outcomes. The simulation results have several potential applications. For example, simulations can be used to generate a null distribution of expected aneuploidy rates for a given patient, given her age and number of embryos tested. This facilitates the selection of patients with extreme aneuploidy phenotypes for genetic studies. Compared with selecting patients with extreme aneuploidy rates, for instance, by directly taking upper and lower quantiles of the aneuploidy rate distribution, our modeling approach allows us to control for the uncertainty due to different number of embryos tested in different patients. Moreover, the simulations can be applied to determine the number of eggs necessary to significantly increase chances of a euploid conception. The simulations also allow us to investigate the contribution of each type of segregation error to different meiosis outcomes. In line with previous reports, we determined that MI errors are far more common than MII errors (8, 9, 41). Our results indicated that MI-PSSC (which also partially accounts for RS in our model) is the most common cause of trisomy in preimplantation embryos and that the relative contribution of each error changes with maternal age. In patients younger than 41 y, MI-PSSC and MII-normal account for most trisomies. In contrast, in patients older than 41 y, a large proportion of single trisomies is derived from MI-PSSC followed by an MII-NDJ error on a different chromosome. This finding further supports the conclusion that MII-NDJ errors might be more prominent than previously appreciated (21).

Limitations of the Model.

To keep the model simple and tractable, we allowed for at most one chromosome error per cell division, which eventually permits any embryo to carry at most two chromosome errors. As a result, all embryos with complex aneuploidies (affecting three or more chromosomes) were jointly considered as a complex category (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A, green bars). This limitation arises from the fact that our mathematical model involves enumerating all possible outcomes of each error mechanism (Fig. 1, depicting a total of 27 outcomes, 30 when we consider RS). Thus, modeling complex aneuploidies as separate events quickly becomes intractable. More importantly, the assumption of independent chromosome missegregation is unlikely to hold for these complex patterns, as certain mechanisms of severe meiotic error (e.g., meiotic spindle instability and abnormal kinetochore-microtubule attachments; ref. 42) impact multiple chromosomes simultaneously and likely violate the assumption of independent chromosome missegregation. For these reasons, we decided to treat complex karyotypes as a broad category and describe it with a single parameter c (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A, green bars).

Another assumption we made in the current model is that each chromosome has an equal chance of being affected by a particular error mechanism. We note that the dataset we used is enriched with single aneuploidies involving chromosomes 15, 16, 21, and 22 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A), which is in line with previous reports (e.g., refs. 41 and 43). We thus also investigated how the model behaves when we relax this assumption and allow for chromosome-specific error rates. To maximize the counts for parameter estimation task, we grouped chromosomes based on either centromere position (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) or chromosome size (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). In the first analysis, we grouped single aneuploidies for acrocentric (chromosome 13, 14, 15, 21, 22), metacentric (chromosome 1, 3, 16, 19, 20), submetacentric (chromosome 2, 4 to 12, 17, 18), and sex chromosomes (chromosome X and Y; SI Appendix, Fig. S5A) and expressed these categories with chromosome type-specific parameters in the model (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 B and C). As expected, estimated chromosome-specific MI error rates roughly sum up to the MI-NDJ and MI-PSSC rates we reported in the main text (compare Fig. 2C with SI Appendix, Fig. S5 B and C), and the estimated incidence of MII-NDJ within the euploid egg was even further reduced (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D). However, even this simple chromosome grouping approach more than doubled the number of model parameters (11 parameters vs. 5 for Model 2). In the latter scenario (SI Appendix, Fig. S6), we tabulated the results when we grouped chromosomes based on their size (a model with 13 parameters). Short chromosomes (Group 5 in SI Appendix, Fig. S6) were the most frequently observed in aneuploid states. This group of chromosomes was also most strongly affected by maternal age, consistent with previous observations (44). Nevertheless, because our current dataset is not large enough to accurately infer age-specific individual chromosome error rates, we believe the simpler Model 2 provides a better confidence in capturing the dynamics of the major error mechanisms at the whole-genome level.

Lastly, some other possible sources of aneuploidies were not considered in the current model. For instance, RS (18, 19) produces eggs with karyotypic signatures resembling the ones already captured with the model (Fig. 1 A–C), and the possible meiotic drive associated with RS (18) will impact model estimates (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). The only current estimates of RS-associated meiotic drive are based on a limited number of patients (six patients; ref. 18). As more data on RS and for a wider age span become available, our model can be adapted to further disentangle the MI-PSSC and RS relationship. Similarly, mitotic NDJ errors (45) or lagging chromosomes (46–48) were not considered because both mechanisms can lead to mosaicism (49–51). The mosaicism outcome is not specified in the data we used and thus cannot be addressed by our model. While we sought to eliminate putative mitotic errors from the input data (e.g., by removing all aneuploidies affecting paternally transmitted chromosomes), it is likely that a small fraction of mitotic errors persists in our data and modestly inflate estimates of all meiotic error parameters.

Applying the Model to Other Datasets.

To further assess the validity of the model, we sought to apply our model to other published datasets. One requirement of our approach is the availability of chromosome-resolution aneuploidy calls. Unfortunately, very few published PGT-A studies provide such resolution for a large number of individual embryos. To our knowledge, aside from the Natera dataset, the only other study to meet these criteria is that of ref. 15, albeit without parent-of-origin information. Applying our model to these data, we obtained similar parameter estimates for d, p, q, and q* (SI Appendix, Fig. S7, with values provided in SI Appendix, Table S3), thus supporting the generality of our conclusions. We attribute the subtle differences in these estimates to differences in patient populations, genomic platforms, aneuploidy inference methods, and filtering criteria. With the decreased cost of the next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology, we expect that more datasets will become available in the near future.

Concluding Remarks.

In conclusion, despite the limitations of the existing technologies to assess aneuploidy in the developing embryo, we showed that model simulations can be used to infer the contributions of various error mechanisms to the genesis of human aneuploidies. Our modeling framework captured the dynamics of meiotic errors and showed that different error mechanisms are affected by age to different extents. One intriguing hypothesis emerging from our study is that MII-NDJ errors occurring in aneuploid eggs are far more affected by maternal age than MII-NDJ in their euploid counterparts. It is possible that some compromised factors in cytoplasmic maturation of the oocyte increase the possibility of a segregation error, giving rise to the observed age-dependent increase in NDJ errors in an aneuploid egg. In the future, this modeling framework can be expanded to accommodate more details about the processes leading to aneuploidy and be adapted to other processes, such as mitotic errors or meiotic errors in spermatogenesis. With parameters learned from clinical data, simulations from our model can also be used to predict IVF embryo aneuploidy rates and potentially provide guidance on the expected number of IVF cycles to obtain a euploid conception.

Materials and Methods

Data Source and Embryo Ploidy Determination.

As input to our model, we used published aneuploidy calls from in vitro-fertilized embryos (5- to 10-cell trophectoderm biopsies collected from day-5 blastocysts) tested by Natera (52). These sample-level data included the inferred copy number of each chromosome, as well as the inferred parental origin of each homolog. The inferences were obtained with the Parental Support algorithm, which contrasts Bayesian probabilities of ploidy hypotheses for each embryonic chromosome, given the observed parent and embryo genotype data (53, 54). This method has been shown to achieve high sensitivity and specificity in a preclinical validation study using cell lines of known ploidy (53). Broadly, the algorithm performs pedigree-based phasing of parental chromosomes, then leverages genotypes at informative parental markers (e.g., when one parent is heterozygous and the other is homozygous) to infer transmission of specific parental homologs. Unlike signal intensity-based approaches, such as array-comparative genomic hybridization and low-coverage NGS, single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotype-based methods such as Parental Support and Karyomapping (55) are performed independently for each chromosome and are thus relatively robust to complex events. This advantage is particularly pronounced for karyotype-wide events such as haploidy, which is generally undetectable with intensity-based approaches but easily detectable by SNP genotyping (53).

Data Parsing.

Original karyotypes of the trophectoderm (day-5) cells are from ref. 52 and were parsed with RStudio (Version 1.0.136) with modified original codes (https://github.com/rmccoy7541/aneuploidy_analysis). Briefly, entries with no-call for at least one chromosome, duplicate entries, and entries for which maternal age was not registered were removed. Entries with indications of errors affecting paternal chromosomes, and with segmental aneuploidies, were also removed. Entries with normal and abnormal karyotypes were then counted. Abnormal karyotypes were divided into two single-error categories: single-chromosome trisomy, single-chromosome monosomy; three double-error categories: double trisomy, double monosomy, trisomy for one chromosome, and monosomy for a second chromosome; and one complex category that accounts for all of the remaining observed karyotypes (Table 2). As such, complex category involves all embryos that had three or more aneuploid chromosomes (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C). Refer to the discussion in Limitations of the Model for more details on the rationale behind using the complex category.

Model Selection.

Models with different qi, i = {1,2,3} combinations were considered. Mathematica (56) and its built-in function NMinimize were used to fit the models to the raw counts by searching a global minimum of the objective function (Table 2, underlined entries). The function to optimize was the residual sum of squares between the nine embryo categories and model simulations, RSSnine. To ensure that probabilities remained in the range from zero to one, following constraints on the search space were enforced:

and in Model 2 or 3, also:

and

AIC.

Model comparison and selection was done by adopting AIC. To avoid overfitting, a corrected version of AIC was used (AICc) for the model selection (57):

Essentially, AICc corrects for the sample size n and the number of parameters k used in the fitting process. The smallest AICc value was used to select the best model given the data.

χ2 Goodness-of-Fit Test.

The χ2 statistics was used to measure the statistical significance of the deviation of the estimated embryo categories from the observations. Statistical difference between both counts was evaluated using the function chisq.test() in RStudio (Version 1.0.136).

Age-Dependent Inference of Model Parameters.

Age-specific parameters were estimated with Mathematica and its function FindMinimum. Raw day-5 data, grouped by maternal age, were used in the estimation process with only the major four embryo categories considered (0, 1, 2, and more than 2 errors; SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). All parameters were set to 0 as initial condition for the FindMinimum algorithm. The RSSfour was then minimized for each age category in separate runs. The constrains on the parameter search space were as in Model Selection.

Adjustment of MII Rates.

To be able to directly compare our estimates of MII errors with reported incidence of MII errors in the literature, we adjusted the MII rates by accounting for the MI outcome. As such, for MII-NDJ within a euploid egg and expressed with in the model, the adjusted rate becomes . Similarly, for MII-NDJ within an aneuploid egg and expressed with , the adjusted rate becomes .

Model Simulation for Single-Oocyte Outcome.

The oogenesis model was simulated as a stochastic process with the program Mathematica using its build-in function RandomChoice, without considering RS. For instance, MI can follow one of the four routes {“no error”, “NDJ”, “PSSC”, “complex”} with probabilities corresponding to the estimated parameter values {1-d-p-c, d, p, c}, respectively. The egg derived from the route “no error,” when fertilized, will complete MII, giving rise to one of the following outcomes: {euploid, trisomic, monosomic} zygote with probabilities {1 − 23q, 23q/2, 23q/2}, respectively. A similar procedure was applied for the oocyte affected by either “NDJ” or “PSSC.”

Single-Patient Simulation.

Considering a single patient, the basic model simulation was repeated N times, where N indicates the number of embryos evaluated for that patient. Age-specific parameters estimates (SI Appendix, Table S2) were used in the simulations. Aneuploidy rate of the simulated patient was calculated as:

Extreme Sample Identification.

The model was simulated 10,000 times to generate empirical null distributions of aneuploidy rates, for each combination of maternal age and number of embryos tested. Age-specific parameters used for model simulations are listed in SI Appendix, Table S2. The empirical null distributions were then used to define the upper and lower critical value for each patient’s aneuploidy rate given her age and number of embryos tested. As a cutoff, 5% of the right or left tail of the null distribution was used, respectively. Individuals with aneuploidy rates equal to or above the upper critical value were considered as having an extreme-high aneuploidy rate. Analogously, individuals with aneuploidy rates equal to or below the lower critical value were considered as having an extreme-low aneuploidy rate.

Derivation of Mean Probability of Euploid Conception for Patients with Unknown Aneuploidy Rates.

Considering an IVF cycle as n Bernoulli trials with a probability p of k successes (i.e., having k euploid embryos) it follows:

where n corresponds to the total number of eggs. Thus, the probability of having at least one euploid embryo can be expressed with the formula: P(at least one is euploid) = 1 − P(not a single one is euploid), i.e., . We then use the estimated null distributions of aneuploidy rates (described in Extreme Sample Identification) to derive the mean probability of having at least one euploid embryo with the simple formula:

where are probabilities of observing the possible aneuploidy rates , given there were n eggs obtained during a course of a single IVF cycle.

Data Availability.

All codes and scripts associated with this study can be accessed at https://gitlab.com/k.m.t/modeling_female_meiosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Premal Shah and David Axelrod for discussions and the Origins of Aneuploidy Research Consortium for facilitating this collaboration. This work is supported by NIH/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R01-HD091331 (to K.S. and J.X.) and NIH/National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant R35-GM133747 (to R.C.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: All codes and scripts associated with this study have been deposited in GitLab (https://gitlab.com/k.m.t/modeling_female_meiosis).

See online for related content such as Commentaries.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1912853117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Barbieri R. L., “Female infertility” in Yen and Jaffe’s Reproductive Endocrinology, Strauss J. F., Barbieri R. L., Eds. (Elsevier, ed. 8, 2019), chap. 22, pp. 556.e557–581.e557. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassold T., Hunt P., To err (meiotically) is human: The genesis of human aneuploidy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 280–291 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagaoka S. I., Hassold T. J., Hunt P. A., Human aneuploidy: Mechanisms and new insights into an age-old problem. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 493–504 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angell R. R., Templeton A. A., Aitken R. J., Chromosome studies in human in vitro fertilization. Hum. Genet. 72, 333–339 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuliev A., Zlatopolsky Z., Kirillova I., Spivakova J., Cieslak Janzen J., Meiosis errors in over 20,000 oocytes studied in the practice of preimplantation aneuploidy testing. Reprod. Biomed. Online 22, 2–8 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubicek D., et al. , Incidence and origin of meiotic whole and segmental chromosomal aneuploidies detected by karyomapping. Reprod. Biomed. Online 38, 330–339 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernardini L., et al. , Frequency of hyper-, hypohaploidy and diploidy in ejaculate, epididymal and testicular germ cells of infertile patients. Hum. Reprod. 15, 2165–2172 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassold T., Hall H., Hunt P., The origin of human aneuploidy: Where we have been, where we are going. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, R203–R208 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall H. E., et al. , The origin of trisomy 22: Evidence for acrocentric chromosome-specific patterns of nondisjunction. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 143A, 2249–2255 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCoy R. C., et al. , Evidence of selection against complex mitotic-origin aneuploidy during preimplantation development. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005601 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell A. D., et al. , Insights about variation in meiosis from 31,228 human sperm genomes. bioRxiv, 10.1101/625202 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Human Fertility Database (Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Germany, and Vienna Institute of Demography, Austria). https://humanfertility.org. Accessed 29 July 2019.

- 13.Mathews T. J., Hamilton B. E., Mean age of mothers is on the rise: United States, 2000-2014. NCHS Data Brief 232, 1–8 (2016). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin J. A., Hamilton B. E., Osterman M. J. K., Driscoll A. K., Drake P., Births: Final data for 2017. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 67, 1–50 (2018). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franasiak J. M., et al. , The nature of aneuploidy with increasing age of the female partner: A review of 15,169 consecutive trophectoderm biopsies evaluated with comprehensive chromosomal screening. Fertil. Steril. 101, 656–663.e1 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chu D. B., Burgess S. M., A computational approach to estimating nondisjunction frequency in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. G3 (Bethesda) 6, 669–682 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boynton P. J., Janzen T., Greig D., Modeling the contributions of chromosome segregation errors and aneuploidy to Saccharomyces hybrid sterility. Yeast 35, 85–98 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ottolini C. S., et al. , Genome-wide maps of recombination and chromosome segregation in human oocytes and embryos show selection for maternal recombination rates. Nat. Genet. 47, 727–735 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gruhn J. R., et al. , Chromosome errors in human eggs shape natural fertility over reproductive life span. Science 365, 1466–1469 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffin D. K., Ogur C., Chromosomal analysis in IVF: Just how useful is it? Reproduction 156, F29–F50 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fragouli E., et al. , The origin and impact of embryonic aneuploidy. Hum. Genet. 132, 1001–1013 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angell R. R., Predivision in human oocytes at meiosis I: A mechanism for trisomy formation in man. Hum. Genet. 86, 383–387 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angell R. R., Xian J., Keith J., Chromosome anomalies in human oocytes in relation to age. Hum. Reprod. 8, 1047–1054 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angell R. R., Xian J., Keith J., Ledger W., Baird D. T., First meiotic division abnormalities in human oocytes: Mechanism of trisomy formation. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 65, 194–202 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Angell R., First-meiotic-division nondisjunction in human oocytes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 61, 23–32 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pellestor F., Andréo B., Arnal F., Humeau C., Demaille J., Maternal aging and chromosomal abnormalities: New data drawn from in vitro unfertilized human oocytes. Hum. Genet. 112, 195–203 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Cruz R., et al. , Cytogenetic analyses of human oocytes provide new data on non-disjunction mechanisms and the origin of trisomy 16. Hum. Reprod. 25, 179–191 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gianaroli L., et al. , Predicting aneuploidy in human oocytes: Key factors which affect the meiotic process. Hum. Reprod. 25, 2374–2386 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurvich C. M., Tsai C.-L., Regression and time series model selection in small samples. Biometrika 76, 297–307 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cimadomo D., et al. , Impact of maternal age on oocyte and embryo competence. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 9, 327 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demko Z. P., Simon A. L., McCoy R. C., Petrov D. A., Rabinowitz M., Effects of maternal age on euploidy rates in a large cohort of embryos analyzed with 24-chromosome single-nucleotide polymorphism-based preimplantation genetic screening. Fertil. Steril. 105, 1307–1313 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiang T., Duncan F. E., Schindler K., Schultz R. M., Lampson M. A., Evidence that weakened centromere cohesion is a leading cause of age-related aneuploidy in oocytes. Curr. Biol. 20, 1522–1528 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lister L. M., et al. , Age-related meiotic segregation errors in mammalian oocytes are preceded by depletion of cohesin and Sgo2. Curr. Biol. 20, 1511–1521 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duncan F. E., et al. , Chromosome cohesion decreases in human eggs with advanced maternal age. Aging Cell 11, 1121–1124 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zielinska A. P., Holubcova Z., Blayney M., Elder K., Schuh M., Sister kinetochore splitting and precocious disintegration of bivalents could explain the maternal age effect. eLife 4, e11389 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zielinska A. P., et al. , Meiotic kinetochores fragment into multiple lobes upon cohesin loss in aging eggs. Curr. Biol. 29, 3749–3765.e7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brieño-Enríquez M. A., Cohen P. E., Double trouble in human aneuploidy. Nat. Genet. 47, 696–698 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zanders S. E., Malik H. S., Chromosome segregation: Human female meiosis breaks all the rules. Curr. Biol. 25, R654–R656 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hassold T., Hunt P., Maternal age and chromosomally abnormal pregnancies: What we know and what we wish we knew. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 21, 703–708 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rabinowitz M., et al. , Origins and rates of aneuploidy in human blastomeres. Fertil. Steril. 97, 395–401 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hou Y., et al. , Genome analyses of single human oocytes. Cell 155, 1492–1506 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holubcová Z., Blayney M., Elder K., Schuh M., Human oocytes. Error-prone chromosome-mediated spindle assembly favors chromosome segregation defects in human oocytes. Science 348, 1143–1147 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pellestor F., Andréo B., Arnal F., Humeau C., Demaille J., Mechanisms of non-disjunction in human female meiosis: The co-existence of two modes of malsegregation evidenced by the karyotyping of 1397 in-vitro unfertilized oocytes. Hum. Reprod. 17, 2134–2145 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Capalbo A., et al. , Sequential comprehensive chromosome analysis on polar bodies, blastomeres and trophoblast: Insights into female meiotic errors and chromosomal segregation in the preimplantation window of embryo development. Hum. Reprod. 28, 509–518 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munné S., Sandalinas M., Escudero T., Márquez C., Cohen J., Chromosome mosaicism in cleavage-stage human embryos: Evidence of a maternal age effect. Reprod. Biomed. Online 4, 223–232 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cimini D., et al. , Merotelic kinetochore orientation is a major mechanism of aneuploidy in mitotic mammalian tissue cells. J. Cell Biol. 153, 517–527 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coonen E., et al. , Anaphase lagging mainly explains chromosomal mosaicism in human preimplantation embryos. Hum. Reprod. 19, 316–324 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daphnis D. D., et al. , Detailed FISH analysis of day 5 human embryos reveals the mechanisms leading to mosaic aneuploidy. Hum. Reprod. 20, 129–137 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vázquez-Diez C., FitzHarris G., Causes and consequences of chromosome segregation error in preimplantation embryos. Reproduction 155, R63–R76 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCoy R. C., Mosaicism in preimplantation human embryos: When chromosomal abnormalities are the norm. Trends Genet. 33, 448–463 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Munné S., Wells D., Detection of mosaicism at blastocyst stage with the use of high-resolution next-generation sequencing. Fertil. Steril. 107, 1085–1091 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCoy R. C., et al. , Common variants spanning PLK4 are associated with mitotic-origin aneuploidy in human embryos. Science 348, 235–238 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnson D. S., et al. , Preclinical validation of a microarray method for full molecular karyotyping of blastomeres in a 24-h protocol. Hum. Reprod. 25, 1066–1075 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rabinowitz M., Banjevic M., Demko Z., Johnson D., “System and method for cleaning noisy genetic data from target Individuals using genetic data from genetically related individuals.” US Patent 9.424,392 B2 (2016).

- 55.Handyside A. H., et al. , Karyomapping: A universal method for genome wide analysis of genetic disease based on mapping crossovers between parental haplotypes. J. Med. Genet. 47, 651–658 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolfram Research Inc. , Mathematica Version 11.3 (Wolfram Research, Inc., Champaign, IL, 2018).

- 57.Burnham K. P., Anderson D. R., Multimodel inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol. Methods Res. 33, 261–304 (2004). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All codes and scripts associated with this study can be accessed at https://gitlab.com/k.m.t/modeling_female_meiosis.