Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was reported at the end of 2019 in China for the first time and has rapidly spread throughout the world as a pandemic. Since COVID-19 causes mild to severe acute respiratory syndrome, most studies in this field have only focused on different aspects of pathogenesis in the respiratory system. However, evidence suggests that COVID-19 may affect the central nervous system (CNS). Given the outbreak of COVID-19, it seems necessary to perform investigations on the possible neurological complications in patients who suffered from COVID-19. Here, we reviewed the evidence of the neuroinvasive potential of coronaviruses and discussed the possible pathogenic processes in CNS infection by COVID-19 to provide a precise insight for future studies.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Neuroinvasion, Nervous system, COVID-19, Transmission routes

Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) belong to a large family of viruses that cause diseases in mammals and birds (Liu et al. 2020). CoVs are responsible for severe respiratory illness such as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in humans. Six types of these viruses affect human cases, such as 229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV (Matoba et al. 2015; Myint 1995). A novel CoV (SARS-CoV-2) also known as COVID-19 has been reported in China in December 2019 for the first time (Lam et al. 2020). Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared that new coronavirus disease is a pandemic. The symptoms of COVID-19 are very similar to MERS and SARS including shortness of breath, breathing difficulties, cough, fatigue, sore throat, and fever. Likewise, some symptoms such as headaches, nausea, confusion, dizziness, and vomiting are reported (Jiang et al. 2020). Studies have shown that MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV, and COVID-19 may cause acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), hepatic, and intestinal diseases (Leung et al. 2003; Peiris et al. 2003; Wu et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2020). It has been indicated that 229E-CoV, OC43-CoV, and SARS-CoV lead to neurological complications in some patients and animal models (Bonavia et al. 1997; Desforges et al. 2014; Jacomy et al. 2006; Jevšnik et al. 2016; Li et al. 2016b; St-Jean et al. 2004) (Table 1). Since the structure and pathogenesis of most CoVs are similar (Butler et al. 2006; St-Jean et al. 2004; Yuan et al. 2017) and the behavior of COVID-19 is unknown, attention to the other organs which may be involved (e.g., central nervous system) and follow-up of patients for neurological complication by designing perspective cohort studies are essential. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to review neuroinvasive potential and neurotropism effects of human coronaviruses (HCoVs) and discuss the probable neurological complication followed by COVID-19 to give an insight for future studies.

Table 1.

Neurological manifestations and pathological findings related to human coronaviruses family infections

| Human coronaviruses | Type of Study | Clinical signs/pathological findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoV-229E | Postmortem analysis of brain samples | Neuroinvasion in multiple sclerosis | (Arbour et al. 2000) |

| CoV-OC43 | Postmortem analysis of brain samples or CSF sampling | Neuroinvasion in multiple sclerosis, demyelination, and encephalomyelitis | (Arbour et al. 2000; Yeh et al. 2004) |

| SARS-CoV | Clinical human study and postmortem analysis | Generalized tonic-clonic seizure, CSF infection, glial cells hyperplasia, neural cell necrosis, neuroinflammation, brain edema | (Gu et al. 2005; Lau et al. 2004; J. Xu et al. 2005) |

| MERS-CoV | Clinical human studies | Ataxia, confusion, dizziness, headache | (Algahtani et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2017) |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Clinical human studies | Headaches, nausea, confusion, dizziness, impaired consciousness, ataxia, acute cerebrovascular diseases, vomiting, epilepsy, and skeletal muscle symptoms | (Guan et al. 2020; Li et al. 2020; Mao et al. 2020a; Mao et al. 2020b) |

Search strategy and selection criteria

References for this review were classified through searches of PubMed and Google Scholar for articles published from 1967 to April 15, 2020. We used the terms “coronavirus,” “SARS,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “MERS,” “229E-CoV,” and “COVID-19,” with combination the terms “nervous system,” “neuroinvasion,” and “neurological manifestation.” In vitro studies on neurotropism potentials of CoVs on neural or glial cells cultures were considered. Furthermore, in vivo investigations were included for injection routes (intranasal and intraperitoneally) of neuroinvasion. Finally, clinical finding searched and included for neurological signs related to CoVs infections.

How can CoVs enter the CNS?

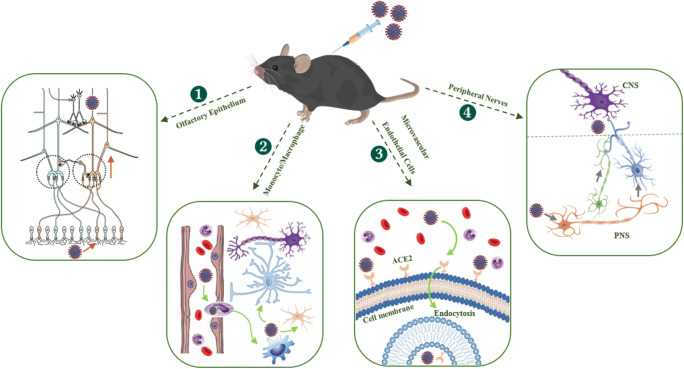

Data from clinical and animal studies have shown that CoVs can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and exert neuroinvasive properties (Cabirac et al. 1994; Cavanagh 2005; Desforges et al. 2013; Li et al. 2016b; Niu et al. 2020; Talbot et al. 2011; J. Xu et al. 2005). The precise mechanisms of penetration into the CNS have not been fully understood. However, four routes of transmission have been suggested. First of all, olfactory nerves are an accessible route for the invasion of CoVs into the CNS (Fig.1 (1)). Intranasal inoculation of mice with MERS-CoV causes brain infection with the involvement of thalamus and brain stem (Li et al. 2016a). Furthermore, it has been reported that the rate of mortality in mice was increased when infected with SARS-CoV through intranasal inoculation. It might be due to neuroinvasion and neural death in the brain stem (Netland et al. 2008). Cellular invasion is the second way to enter the CNS (Fig. 1 (2)). In this way, infected monocytes/macrophages by CoVs cross the BBB and exert neuroinvasive properties. MERS-CoV can infect monocyte and T lymphocyte in human cell lines (Chan et al. 2013). In vitro studies have reported that infected human monocytes/macrophages can act as a viral reservoir and spread viruses to other tissues (Collins 2002; Desforges et al. 2007). The third possible way which mediates neuroinvasion of CoVs is microvascular endothelial cells of BBB structure (Fig.1 (3)). These cells can express two types of SARS-CoV receptors, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and CD209L (J. Li et al. 2007). Therefore, SARS-CoVs can enter the CNS through interaction with ACE2 and CD209L receptors. The last transmitting way into the CNS is trans-synaptic transmission through peripheral nerves (Figs.1 (4)). Injection of hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus (HEV) in hindfoot of rat leads to the emersion of the virus in the motor cortex through coated vesicles in trans-synaptic route (Li et al. 2013).

Fig. 1.

Transmission routes of coronaviruses into the CNS. (1) Intranasal inoculation of coronaviruses can lead to neuroinvasion through primary olfactory neurons in the olfactory epithelium and mitral/tufted cells in the olfactory bulb. (2) Infected monocytes can cross from BBB via diapedesis and infect glial and neuronal cells. (3) Interaction between CoV and ACE2 receptors on BBB endothelial cells can enter into the CNS. (4) Finally, viruses can enter the CNS through peripheral nerves via trans-synaptic transmission. ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; CNS, central nervous system; PNS, peripheral nervous system

Human coronavirus family has neuroinvasion potential

Evidence suggests that several types of infected human coronavirus have neuroinvasion potential. For example, the type of human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) causes neurological manifestation through neuroinvasion. Several studies have been indicated that human neural cell culture was infected by HCoV-229E (Arbour et al. 1999; Bonavia et al. 1997; Lachance et al. 1998). It has also been reported that HCoV-229E can increase the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in monocytes (Desforges et al. 2007). Also, postmortem analysis of brain multiple sclerosis patients showed a presence of HCoV (Arbour et al. 2000). Another human coronavirus which is very similar to HCoV-229E known as OC43 (HCoV-OC43) is responsible for the common cold and lower respiratory tract infections such as pneumonia (Vabret et al. 2003). It has been reported that neuronal cells derived from mouse dorsal root ganglia and human astrocyte cells produced HCoV-OC43 antigen and infectious virus (Pearson and Mims 1985) (Bonavia et al. 1997). The production of pro-inflammatory cytokines increased and induced neural injuries when human astrocyte culture was infected by HCoV-OC43 (Edwards et al. 2000). HCoV-OC43 (Jacomy et al. 2006; Stodola et al. 2018) caused neuropathy and gliopathy by activating the apoptosis cascades in cell cultures (Jacomy et al. 2006). Furthermore, neuroinflammation following by neuroinvasion has been shown in mice when HCoV-OC43 was inoculated intraperitoneally (Jacomy and Talbot 2003). Encephalitis, neuronal degeneration, microglia activation, and decreasing locomotor activity were also observed following the administration of HCoV-OC43 in mice (Jacomy et al. 2006). Identically, intranasal inoculation of virus leads to neuroinvasion (Butler et al. 2006; St-Jean et al. 2004). In a postmortem study, a higher prevalence of HCoV-OC43 was seen in the brain multiple sclerosis patients (Arbour et al. 2000). In a case report study, the test of HCoV-OC43 was positive in a child with encephalomyelitis (Yeh et al. 2004).

Another example of a neuroinvasive function is SARS-CoV which is identified in southern China and caused more than 900 deaths in the world until Jun 2003 (Chan-Yeung and Xu 2003) (Vu et al. 2004). SARS-CoVs could penetrate into the CNS and cause neuropathy and gliopathy (Guo et al. 2008). An increase of pro-inflammatory cytokines was observed after intranasal inoculation of SARS-CoV in mice brains. The presence of the virus in the brain tissue was confirmed by RT-PCR (McCray et al. 2007) (Netland et al. 2008). Generalized tonic-clonic convulsion has been reported in a patient who suffered from SARS disease. In this case, the presence of SARS-CoV in cerebrospinal fluid was positive (Lau et al. 2004). Also, glial cells hyperplasia and neural cell necrosis in a cytokine manner mechanism were detected in the brain sample from a patient with SARS (Xu et al. 2005). A postmortem analysis has also been shown that SARS-CoV is capable to infect the neural cells in the hypothalamus and cortex and cause brain edema in patients with SARS disease (Gu et al. 2005). Additionally, MERS-CoV as an HCoVs can infect human neuronal cell line culture (Zaki et al. 2012) (Chan et al. 2013). Also, a report study indicated that two patients with MERS-CoV infection had severe neurological manifestations (Algahtani et al. 2016). In the same way, it has been reported that some neurological implications, such as weakness of limbs or hand and hyperreflexia in deep tendon reflex were seen in patients with MERS-CoV infection (Kim et al. 2017).

It is interesting to note that neurological signs, such as headache (Chen et al. 2020; Huang et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020; Woelfel et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2020), confusion, dizziness, impaired consciousness, ataxia, epilepsy, and skeletal muscle symptoms in patients with COVID-19 were reported (Guan et al. 2020; Li et al. 2020; Liang et al. 2020; Mao et al. 2020a; Mao et al. 2020b). It might be due to neuroinvasive property. However, few researchers have been able to draw on any systematic research into this topic. But it has been recently suggested that the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with ACE2 receptors on the neural cells can involve in the pathophysiology of neuroinvasion and neural damages following COVID-19 infection (Baig et al. 2020). Besides that, an unpublished report from Beijing Ditan Hospital showed that the encephalitis was observed in a patient with COVID-19 (Huaxia 2020). Also, neuroimaging techniques and EEG data in two new cases revealed hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy (Poyiadji et al. 2020), epileptogenicity, and encephalomalacia (Filatov et al. 2020) in relation to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Furthermore, in two currently cases, a 74-year-old man and a 58-year-old woman have been confirmed with neurological manifestations as a consequence of the SARS-CoV-2 infection (Lanese 2020; Rahhal 2020). The 74-year-old patient had temporarily lost the ability to speak in Florida (Rahhal 2020). The case of 58-year-old woman had confusion, lethargy, and disorientation signs. The brain CT scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed injury in the thalamus, hemorrhage, and necrotizing encephalopathy (Lanese 2020). In contrast to another type of HCoVs, there is much less information about the effects of neuroinvasive and neurotropism of COVID-19.

Conclusion remarks and future perspective

Taken together, data from the above-mentioned studies confirm the neuroinvasive properties of HCoVs and their effects on CNS. Although the exact mechanism of neuroinvasion is still unclear, some penetration routes, such as olfactory epithelium, cellular infection, BBB structure, and trans-synaptic transmission, have been suggested. Considerably, more work will need to be done to determine the long-term effects of COVID-19 on CNS. Therefore, we suggest that a well-designed cohort study can provide powerful results for their effects. In the same way, further experiments using in vitro, in vivo, and postmortem studies could shed more light on the possible neuroinvasion and neural injuries after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Abbreviations

- ACE2

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BBB

Blood-brain barrier

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CoV

Coronavirus

- CoVs

Coronaviruses

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- HCoVs

Human coronaviruses

- HCoV-OC43

Human coronavirus OC43

- HCoV-229E

Human coronavirus 229E

- MERS

Middle East respiratory syndrome

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

Authors’ contributions

Ali Sepehrinezhad and Sajad Sahab Negah designed the study, performed the literature review, and drafted the manuscript. Also, Ali Shahbazi and Sajad Sahab Negah critically edited the manuscript and corrected grammatical errors in the revised manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated during the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Algahtani H, Subahi A, Shirah B. Neurological complications of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2016;2016:3502683–3502686. doi: 10.1155/2016/3502683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbour N, Ekandé S, Côté G, Lachance C, Chagnon F, Tardieu M, et al. Persistent infection of human oligodendrocytic and neuroglial cell lines by human coronavirus 229E. J Virol. 1999;73(4):3326–3337. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.4.3326-3337.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbour N, Day R, Newcombe J, Talbot PJ. Neuroinvasion by human respiratory coronaviruses. J Virol. 2000;74(19):8913–8921. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.19.8913-8921.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig AM, Khaleeq A, Ali U, Syeda H (2020) Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: tissue distribution, host-virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS chemical neuroscience [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bonavia A, Arbour N, Yong VW, Talbot PJ. Infection of primary cultures of human neural cells by human coronaviruses 229E and OC43. J Virol. 1997;71(1):800–806. doi: 10.1128/JVI.71.1.800-806.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler N, Pewe L, Trandem K, Perlman S. Murine encephalitis caused by HCoV-OC43, a human coronavirus with broad species specificity, is partly immune-mediated. Virology. 2006;347(2):410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabirac GF, Soike KF, Zhang JY, Hoel K, Butunoi C, Cai GY, Johnson S, Murray RS. Entry of coronavirus into primate CNS following peripheral infection. Microb Pathog. 1994;16(5):349–357. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D. Coronaviruses in poultry and other birds. Avian Pathol. 2005;34(6):439–448. doi: 10.1080/03079450500367682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JF, Chan KH, Choi GK, To KK, Tse H, Cai JP, et al. Differential cell line susceptibility to the emerging novel human betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012: implications for disease pathogenesis and clinical manifestation. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(11):1743–1752. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan-Yeung M, Xu RH. SARS: epidemiology. Respirology. 2003;8(Suppl):S9–S14. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, Xia J', Yu T, Zhang X, Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AR. In vitro detection of apoptosis in monocytes/macrophages infected with human coronavirus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9(6):1392–1395. doi: 10.1128/cdli.9.6.1392-1395.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desforges M, Miletti TC, Gagnon M, Talbot PJ. Activation of human monocytes after infection by human coronavirus 229E. Virus Res. 2007;130(1–2):228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desforges M, Favreau DJ, Brison É, Desjardins J, Meessen-Pinard M, Jacomy H, Talbot PJ (2013) Human coronaviruses: respiratory pathogens revisited as infectious neuroinvasive, neurotropic, and neurovirulent agents neuroviral infections (pp. 112-141): CRC press

- Desforges M, Le Coupanec A, Brison E, Meessen-Pinard M, Talbot PJ. Neuroinvasive and neurotropic human respiratory coronaviruses: potential neurovirulent agents in humans. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;807:75–96. doi: 10.1007/978-81-322-1777-0_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JA, Denis F, Talbot PJ. Activation of glial cells by human coronavirus OC43 infection. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;108(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(00)00266-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filatov A, Sharma P, Hindi F, Espinosa PS. Neurological complications of coronavirus disease (covid-19): encephalopathy. Cureus. 2020;12(3):e7352. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Gong E, Zhang B, Zheng J, Gao Z, Zhong Y, Zou W, Zhan J, Wang S, Xie Z, Zhuang H, Wu B, Zhong H, Shao H, Fang W, Gao D, Pei F, Li X, He Z, Xu D, Shi X, Anderson VM, Leong AS. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Exp Med. 2005;202(3):415–424. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan W-j, Ni Z-y, Hu Y, Liang W-h, Ou C-q, He J-x et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. medRxiv, 2020.2002.2006.20020974. 10.1101/2020.02.06.20020974

- Guo Y, Korteweg C, McNutt MA, Gu J. Pathogenetic mechanisms of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Virus Res. 2008;133(1):4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huaxia (2020) Beijing hospital confirms nervous system infections by novel coronavirus. Available via DIALOG.http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-03/05/c_138846529.htm. Accessed 5 Mar 2020

- Jacomy H, Talbot PJ. Vacuolating encephalitis in mice infected by human coronavirus OC43. Virology. 2003;315(1):20–33. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00323-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacomy H, Fragoso G, Almazan G, Mushynski WE, Talbot PJ. Human coronavirus OC43 infection induces chronic encephalitis leading to disabilities in BALB/C mice. Virology. 2006;349(2):335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jevšnik M, Steyer A, Pokorn M, Mrvič T, Grosek Š, Strle F, Lusa L, Petrovec M. The role of human coronaviruses in children hospitalized for acute bronchiolitis, acute gastroenteritis, and febrile seizures: a 2-year prospective study. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Deng L, Zhang L, Cai Y, Cheung CW, Xia Z (2020) Review of the clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Gen Intern Med. 10.1007/s11606-020-05762-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim JE, Heo JH, Kim HO, Song SH, Park SS, Park TH, Ahn JY, Kim MK, Choi JP. Neurological complications during treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome. J Clin Neurol. 2017;13(3):227–233. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2017.13.3.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachance C, Arbour N, Cashman NR, Talbot PJ. Involvement of aminopeptidase N (CD13) in infection of human neural cells by human coronavirus 229E. J Virol. 1998;72(8):6511–6519. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.8.6511-6519.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam TT-Y, Shum MH-H, Zhu H-C, Tong Y-G, Ni X-B, Liao Y-S et al (2020) Identification of 2019-nCoV related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins in southern China. bioRxiv, 2020.2002.2013.945485. 10.1101/2020.02.13.945485

- Lanese N (2020) Woman with COVID-19 developed a rare brain condition. Doctors suspect a link. Available via DIALOG. https://www.livescience.com/woman-with-covid19-coronavirus-had-rare-brain-disease.html. Accessed 1 Apr 2020

- Lau KK, Yu WC, Chu CM, Lau ST, Sheng B, Yuen KY. Possible central nervous system infection by SARS coronavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):342–344. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung WK, To K-F, Chan PKS, Chan HLY, Wu AKL, Lee N, Yuen KY, Sung JJY. Enteric involvement of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus infection1 1The authors thank Man-yee Yung, Sara Fung, Dr. Bonnie Kwan, and Dr. Thomas Li for their help in retrieving patient information. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(4):1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Gao J, Xu YP, Zhou TL, Jin YY, Lou JN. Expression of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptors, ACE2 and CD209L in different organ derived microvascular endothelial cells. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2007;87(12):833–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y-C, Bai W-Z, Hirano N, Hayashida T, Taniguchi T, Sugita Y, Tohyama K, Hashikawa T. Neurotropic virus tracing suggests a membranous-coating-mediated mechanism for transsynaptic communication. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521(1):203–212. doi: 10.1002/cne.23171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Wohlford-Lenane C, Perlman S, Zhao J, Jewell AK, Reznikov LR, Gibson-Corley KN, Meyerholz DK, McCray PB., Jr Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus causes multiple organ damage and lethal disease in mice transgenic for human dipeptidyl peptidase 4. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(5):712–722. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Li H, Fan R, Wen B, Zhang J, Cao X, Wang C, Song Z, Li S, Li X, Lv X, Qu X, Huang R, Liu W. Coronavirus infections in the central nervous system and respiratory tract show distinct features in hospitalized children. Intervirology. 2016;59(3):163–169. doi: 10.1159/000453066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YC, Bai WZ, Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92:552–555. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Zhao Y-X, Zhang X-X, Lu J, Gu N (2020) Clinical characteristics of 457 cases with coronavirus disease 2019. Available at SSRN 3543581

- Liu Z, Xiao X, Wei X, Li J, Yang J, Tan H et al (2020) Composition and divergence of coronavirus spike proteins and host ACE2 receptors predict potential intermediate hosts of SARS-CoV-2. J Med Virol n/a(n/a). 10.1002/jmv.25726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, Zhou Y, Wang D, Miao X, Li Y, Hu B (2020a) Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mao L, Wang M, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C et al (2020b) Neurological manifestations of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective case series study. medRxiv, 2020.2002.2022.20026500. 10.1101/2020.02.22.20026500

- Matoba Y, Abiko C, Ikeda T, Aoki Y, Suzuki Y, Yahagi K, Matsuzaki Y, Itagaki T, Katsushima F, Katsushima Y, Mizuta K. Detection of the human coronavirus 229E, HKU1, NL63, and OC43 between 2010 and 2013 in Yamagata, Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2015;68(2):138–141. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2014.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCray PB, Pewe L, Wohlford-Lenane C, Hickey M, Manzel L, Shi L, et al. Lethal infection of K18-<em>hACE2</em> mice infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2007;81(2):813–821. doi: 10.1128/jvi.02012-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myint, S. H. (1995). Human coronavirus infections The Coronaviridae (pp. 389-401): springer

- Netland J, Meyerholz DK, Moore S, Cassell M, Perlman S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection causes neuronal death in the absence of encephalitis in mice transgenic for human ACE2. J Virol. 2008;82(15):7264–7275. doi: 10.1128/jvi.00737-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu J, Shen L, Huang B, Ye F, Zhao L, Wang H, Deng Y, Tan W. Non-invasive bioluminescence imaging of HCoV-OC43 infection and therapy in the central nervous system of live mice. Antivir Res. 2020;173:104646. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.104646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J, Mims CA. Differential susceptibility of cultured neural cells to the human coronavirus OC43. J Virol. 1985;53(3):1016–1019. doi: 10.1128/JVI.53.3.1016-1019.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris JS, Lai ST, Poon LL, Guan Y, Yam LY, Lim W, et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361(9366):1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poyiadji N, Shahin G, Noujaim D, Stone M, Patel S, Griffith B (2020) COVID-19-associated acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy: CT and MRI features. Radiology. 10.1148/radiol.2020201187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rahhal N (2020) Coronavirus may cause brain damage by triggering dangerous inflammation that can cause bleeds and cell death. Available via DIALOG. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-8181257/Coronavirus-damage-brains-patients-reports-suggests.html. Accessed 3 Apr 2020

- St-Jean JR, Jacomy H, Desforges M, Vabret A, Freymuth F, Talbot PJ. Human respiratory coronavirus OC43: genetic stability and neuroinvasion. J Virol. 2004;78(16):8824–8834. doi: 10.1128/jvi.78.16.8824-8834.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stodola JK, Dubois G, Le Coupanec A, Desforges M, Talbot PJ. The OC43 human coronavirus envelope protein is critical for infectious virus production and propagation in neuronal cells and is a determinant of neurovirulence and CNS pathology. Virology. 2018;515:134–149. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot PJ, Desforges M, Brison E, Jacomy H, Tkachev S (2011) Coronaviruses as encephalitis-inducing infectious agents. Non-flavirus Encephalitis In-Tech, 185–202

- Vabret A, Mourez T, Gouarin S, Petitjean J, Freymuth F. An outbreak of coronavirus OC43 respiratory infection in Normandy, France. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(8):985–989. doi: 10.1086/374222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu HT, Leitmeyer KC, Le DH, Miller MJ, Nguyen QH, Uyeki TM, et al. Clinical description of a completed outbreak of SARS in Vietnam, February-May 2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):334–338. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woelfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Zange S, Mueller MA, . . . Wendtner C (2020) Clinical presentation and virological assessment of hospitalized cases of coronavirus disease 2019 in a travel-associated transmission cluster. medRxiv, 2020.2003.2005.20030502. doi:10.1101/2020.03.05.20030502

- Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J a, Zhou X, Xu S et al (2020) Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Int Med. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xu J, Zhong S, Liu J, Li L, Li Y, Wu X, Li Z, Deng P, Zhang J, Zhong N, Ding Y, Jiang Y. Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in the brain: potential role of the chemokine mig in pathogenesis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(8):1089–1096. doi: 10.1086/444461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X-W, Wu X-X, Jiang X-G, Xu K-J, Ying L-J, Ma C-L, Li SB, Wang HY, Zhang S, Gao HN, Sheng JF, Cai HL, Qiu YQ, Li L-J. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020;368:m606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Cao Q, Qin L, Wang X, Cheng Z, Pan A, Dai J, Sun Q, Zhao F, Qu J, Yan F. Clinical characteristics and imaging manifestations of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19):a multi-center study in Wenzhou city, Zhejiang, China. J Infect. 2020;80(4):388–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh EA, Collins A, Cohen ME, Duffner PK, Faden H. Detection of coronavirus in the central nervous system of a child with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1 Pt 1):e73–e76. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.e73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y, Cao D, Zhang Y, Ma J, Qi J, Wang Q, Lu G, Wu Y, Yan J, Shi Y, Zhang X, Gao GF. Cryo-EM structures of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV spike glycoproteins reveal the dynamic receptor binding domains. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15092. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Shi L, Wang F-S (2020) Liver injury in COVID-19: management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30057-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated during the study.