Graphical abstract

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic, Protective measures, Behavior change, Public health

Highlights

-

•

Improvement in personal protective measures since early phase of COVID-19 outbreak.

-

•

The prevalence of avoiding touching the eyes, nose, and mouth is still low.

-

•

Fewer men and fewer low-income households have altered their behavior.

-

•

Self-isolation seems difficult for people with low income levels.

-

•

There remains room for improvement in personal protective measures by citizens.

Abstract

Objectives

To clarify changes in the implementation of personal protective measures among ordinary Japanese citizens from the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak to the community transmission phase.

Methods

This longitudinal, internet-based survey included 2141 people (50.8% men; 20–79 years). The baseline and follow-up surveys were conducted from February 25–27, 2020, and April 1–6, 2020, respectively. Participants were asked how often they implemented the five personal protective measures recommended by the World Health Organization (hand hygiene, social distancing, avoiding touching the eyes, nose and mouth, respiratory etiquette, and self-isolation) in the baseline and follow-up surveys.

Results

Three of the five personal protective measures’ availability significantly improved during the community transmission phase compared to the early phase. Social distancing measures showed significant improvement, from 67.4% to 82.2%. However, the prevalence of avoiding touching the eyes, nose, and mouth, which had the lowest prevalence in the early phase, showed no significant improvement (approximately 60%). Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that men and persons of low-income households made fewer improvements than women and persons of high-income households.

Conclusions

The availability of personal protective measures by ordinary citizens is improving; however, there is potential for improvement, especially concerning avoiding touching eyes, nose, and mouth.

Introduction

With no end in sight to the rapidly evolving coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, a critical element in reducing transmission of the virus is a rapid and widespread behavior change in ordinary citizens (Betsch et al., 2020). Many governments and health authorities have called on ordinary citizens to implement personal protective measures, such as hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette, and social distancing measures, since the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak (JMHLW, 2020a, U.S.CDC, 2020, WHO, 2020a).

We recently reported the results of a survey on the implementation status of personal protective measures by ordinary citizens conducted on February 25, 2020, during the early phase of COVID-19 in Japan (Machida et al., 2020). In that study, we found that in the initial phase of COVID-19 there was low occurrence among ordinary Japanese citizens in the implementation of social distancing measures and avoiding touching the eyes, nose, and mouth, two of the five personal protective measures recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) (World Health Organization (WHO, 2020a). Only 34.7% of survey respondents were implementing all five individual protective measures, which clearly revealed that there was room for improvement regarding personal protective measures implemented by ordinary citizens. Since the time the survey was conducted, the number of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases within Japan has steadily increased, and on March 19, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare called on the Japanese people to change their behavior regarding personal protective measures, to suppress transmission (Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (JMHLW, 2020b). However, after the Ministry’s call, the number of reported COVID-19 cases in Japan rapidly increased mainly in major metropolitan areas, such as Tokyo and Osaka regions, and the pandemic shifted into the community transmission phase. On April 7, the number of reported COVID-19 cases in Japan totaled 3906, which led to the Japanese government to declare a state of emergency (Prime Minister of Japan, 2020). Although unclear, the status of personal protective measures among ordinary citizens may have changed depending on the pandemic phase shift. Therefore, it is important to clarify the current situation in the community transmission phase when considering what is needed in future awareness activities.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to clarify the change in the implementation of personal protective measures among ordinary citizens, from the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak to the community transmission phase in Japan, and to identify steps that have improved in addition to recognizing those that are insufficient.

Methods

Study sample and data collection

This was a longitudinal study based on an internet survey. A baseline survey was implemented from February 25–27, 2020, during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan. On February 25, the number of reported COVID-19 cases in Japan totaled 157 (World Health Organization (WHO, 2020b). The study’s participants were recruited from registrants of MyVoice Communication, Inc., a Japanese internet research service company with approximately 1.12 million registered participants as of January 2020. The study aimed to collect data from 2400 men and women aged 20 to 79 years (sampling by sex and 10-year age groups; 12 groups, n = 200 per group) who were living in seven prefectures in the Tokyo metropolitan area (i.e., Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, Chiba, Ibaraki, Tochigi, and Gunma). The Tokyo metropolitan area is home to approximately 35% of the Japanese population (total area: 32,433.4 km2; total population: 43,512,238 people, as of January 2019). The company invited registrants to participate in the survey by email on February 25 (n = 8156). The questionnaires were placed in a secured section of a website, and potential respondents received a specific URL in their invitation email. Once 200 participants in each group had responded to the questionnaire voluntarily, no more responses were accepted from that group; the survey concluded on February 27 when 200 responses had been collected from all groups.

The company then invited the 2400 respondents of the baseline survey to participate in a follow-up survey by email on April 1, 2020. On that day, the number of reported COVID-19 cases in Japan was 2178, and the number of patients had increased rapidly, mainly in Tokyo (World Health Organization (WHO, 2020b). The questionnaires were again placed in a secure section of a website, and potential respondents received a specific URL in their invitation email. The 2400 respondents to the baseline survey responded to the questionnaire voluntarily; the response cut-off date was April 6. On April 7, a day after the completion of the survey, the Japanese government declared a state of emergency (Prime Minister of Japan, 2020).

Reward points valued at 50 yen were provided as an incentive for participation (approximately 0.5 US dollars, as of April 2020) in both the baseline and follow-up survey.

Measurement

Assessment of the five personal protective measures as recommended by the WHO

Participants self-reported their implementation of the five personal protective measures (hand hygiene, social distancing measures, avoiding touching the eyes, nose, and mouth, respiratory etiquette, and self-isolation) recommended by the WHO (World Health Organization (WHO, 2020a). Regarding the four personal protective measures other than self-isolation, participants were asked about the frequency of implementation during the previous week and responded using a 4-point-Likert scale (1: “Always, 2: “Sometimes,” 3: “Rarely,” or 4: “Never”). As for social distancing measures, participants were asked to disclose the frequency in which they avoided places where many people would be gathered together. Regarding self-isolation, the participants were asked the question, “if you have a fever or a cold, can you take time off from work?” Participants responded using a 5-point Likert scale (1: “Definitely can,” 2: “Probably can,” 3: “Probably can’t,” 4: “Definitely can’t” or 5: “Not working.” Participants answered the same questions in both the baseline survey and the follow-up survey.

Assessment of sociodemographic factors

In the baseline survey, participants gave information about their sex, age, marital status (not married/married), working status (working/not working), smoking status (smokers/non-smokers), past medical history (hypertension, diabetes, and respiratory disease), and residential area (Tokyo/other). In the follow-up survey, participants were asked about their living arrangements (with others/alone). Also, the research company provided categorized data as follows: educational attainment (university graduate or above/below), and household income level (<5 million yen or ≥5 million yen).

Statistical analysis

Regarding the five personal protective measures, when a participant responded with 1 (“Always”/“Definitely can”) or 2 (“Sometimes”/“Probably can”) on the 4-point-Likert scale, it was counted as the personal protective measures had been implemented. In both the baseline survey and follow-up survey, we clarified each protective measure's prevalence and the implementation of all personal protective measures. Regarding self-isolation and implementing all personal protective measures, those who selected 5 (“Not working”) in the baseline survey or follow-up survey were excluded from the analysis (n = 776). The McNemar test was performed to compare the prevalence of each personal protective measure between the baseline survey and the follow-up survey. To clarify the association between each sociodemographic factor and behavior changes related to each personal protective measure, a multivariate logistic regression analysis focused on those who did not implement the personal protective measure in the baseline survey. The dependent variable was set as a dichotomous variable coded as “1” if the personal protective measure was adopted in the follow-up survey and “zero” otherwise. The dependent variable was prepared for each of the five personal protective measures recommended by the WHO and implementing all personal protective measures. Participants who had already implemented a personal protective measure at the time of the baseline survey were excluded in the analysis for that particular protective measure. The independent variables were sex, age (older adults ≥65 years old/persons under 65 years old), marital status (not married/married), working status (working/not working), living arrangement (with others/alone), smoking status (smokers/non-smokers), residential area (Tokyo/other), educational attainment (university graduate or above/below), and household income level (<5 million yen or ≥5 million yen).

Regarding self-isolation, those who selected 5 (“Not working”), in either the baseline survey or follow-up survey, were excluded from the analysis, therefore working status was removed from the aforementioned independent variables. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26 (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Two-sided p values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Participant enrollment and descriptive statistics

Of the 2400 respondents in the baseline survey, valid responses were obtained from 2141 respondents in the follow-up survey (response rate: 89.2%, Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| N = 2141 |

||

|---|---|---|

| n (%)/mean (SD) | ||

| Sex (men) | 1087 | 50.8% |

| Age, years | 49.7 | 16.2 |

| Marital status (married) | 1216 | 56.8% |

| Working status (working) | 1352 | 63.1% |

| Living arrangement (with others) | 1695 | 79.2% |

| Smoking status (smokers) | 318 | 14.9% |

| Past medical history (yes) | ||

| Hypertension | 398 | 18.6% |

| Diabetes | 125 | 5.8% |

| Respiratory disease | 91 | 4.3% |

| Residential area (Tokyo) | 824 | 38.5% |

| Educational attainment (University graduate or above) | 1122 | 52.4% |

| Household income level (≥5 million yen) | 1101 | 51.4% |

SD: standard deviation.

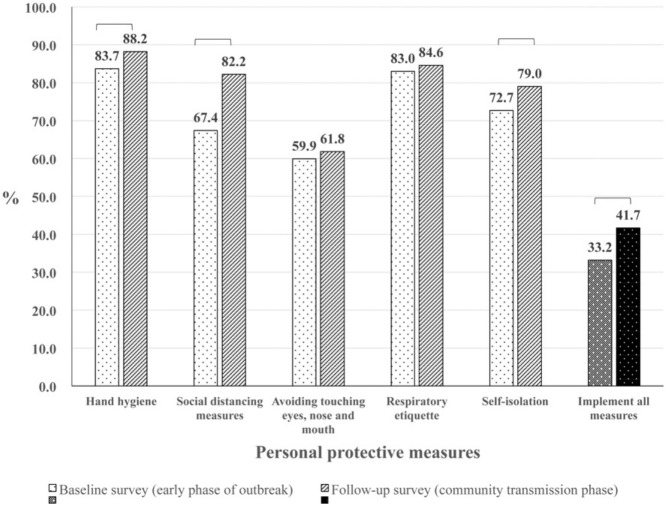

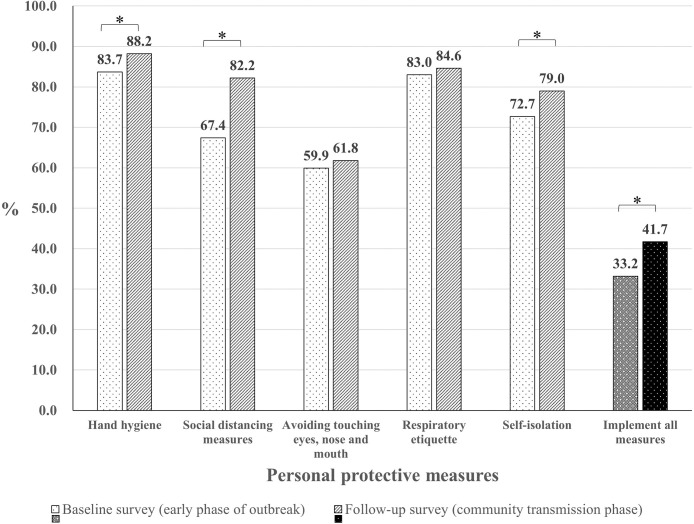

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of each personal protective measure in the baseline survey and the follow-up survey. In the follow-up survey, the prevalence of personal protective measures other than avoiding touching the eyes, nose, and mouth was approximately 80%. The prevalence of hand hygiene, social distancing measures, self-isolation, and implementing all five personal protective measures had increased significantly at the time of the follow-up survey compared with the baseline survey. The prevalence of social distancing measures had risen from 67.4% to 82.2%. However, the implementation rate of avoiding touching the eyes, nose, and mouth was 59.9% in the baseline survey and 61.8% in the follow-up survey, showing no statistically significant difference.

Figure 1.

The baseline survey and follow-up survey: the prevalence of each personal protective measure recommended by the WHO.

When the participant replied “Always,” “Sometimes,” or “Definitely can,” or “Probably can” (in the case of self-isolation) for each personal preventive measure, it was considered that the personal protective measure was being implemented. The McNemar test was performed to compare the prevalence of each personal protective measure. *: p-value = <0.001.

Table 2 shows the association between each sociodemographic factor and behavior change related to each personal protective measure. Concerning social distancing measures and implementing all personal protective measures, women had significantly higher odds ratios (OR) than men (OR; social distancing measures: 1.57; implementing all measures: 1.74). Regarding social distancing measures and self-isolation, persons with high household income levels had a significantly higher OR than those with low household income levels (OR; social distancing measure: 1.49; self-isolation: 1.93).

Table 2.

Association between each sociodemographic factor and change in behavior related to each personal protective measure.

| Hand hygiene | Social distancing measures | Avoiding touching the eyes, nose, and mouth | Respiratory etiquette | Self-isolationa | Implement all measuresa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of persons not implementing a personal protective measure (baseline survey) | 350 | 699 | 858 | 365 | 373 | 912 |

| Total number of persons who started a personal protective measure (follow-up survey) | 198 | 429 | 315 | 186 | 174 | 268 |

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||||||

| Sex: women | 1.30 (0.80–2.13) | 1.57* (1.11–2.21) | 1.30 (0.96–1.78) | 1.39 (0.84–2.29) | 1.07 (0.68–1.68) | 1.74** (1.28–2.38) |

| Age: older adults | 1.55 (0.83–2.89) | 1.46 (0.88–2.42) | 1.15 (0.78–1.70) | 1.98* (1.00–3.93) | 1.16 (0.42–3.17) | 1.62 (0.99–2.65) |

| Marital status: married | 0.55* (0.32–0.95) | 1.13 (0.76–1.67) | 1.35 (0.93–1.95) | 1.09 (0.63–1.88) | 1.61 (0.97–2.69) | 1.15 (0.80–1.65) |

| Working status: working | 1.16 (0.68–2.00) | 0.95 (0.62–1.46) | 0.96 (0.67–1.37) | 2.48* (1.38–4.47) | N/A | N/A |

| Living arrangement: with other | 1.19 (0.67–2.13) | 1.01 (0.64–1.59) | 0.76 (0.50–1.15) | 0.96 (0.54–1.73) | 0.59 (0.32–1.09) | 0.94 (0.62–1.43) |

| Smoking status: smokers | 0.88 (0.48–1.61) | 0.83 (0.55–1.27) | 0.92 (0.63–1.35) | 1.31 (0.72–2.39) | 0.79 (0.46–1.38) | 0.91 (0.61–1.36) |

| Residential area: Tokyo | 1.02 (0.64–1.63) | 1.30 (0.94–1.81) | 0.97 (0.72–1.31) | 0.81 (0.50–1.31) | 1.31 (0.85–2.02) | 1.10 (0.81–1.49) |

| Educational attainment: university graduate or above | 0.85 (0.53–1.36) | 0.78 (0.55–1.10) | 1.03 (0.75–1.40) | 1.33 (0.84–2.10) | 0.85 (0.54–1.35) | 1.00 (0.72–1.37) |

| Household income: ≥ 5 million yen | 1.56 (0.97–2.50) | 1.49* (1.05–2.12) | 1.07 (0.78–1.48) | 0.99 (0.62–1.58) | 1.93* (1.19–3.13) | 1.39 (0.99–1.97) |

p-Value: *: <0.05, **: <0.001.

When the participant replied “Always,” “Sometimes,” or “Definitely can,” or “Probably can” (in the case of self-isolation) for each personal preventive measure, it was considered that the personal protective measure was being implemented.

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed. The dependent variable was set as “not implementing each personal protective measure” at the time of the baseline survey, and “implementing each measure” at the time of the follow-up survey. Participants who had already implemented a personal protective measure at the time of the baseline survey were excluded in the analysis for that particular protective measure. The independent variables were sex, age (older adults ≥65 years old/persons under 65 years old), marital status (not married/married), working status (working/not working), living arrangement (with others/alone), smoking status (smokers/non-smokers), residential area (Tokyo/other), educational attainment (university graduate or above/below), and household income level (<5 million yen or ≥5 million yen).

Regarding self-isolation, in response to the question “If you have a fever or cold, can you take time off from work?” participants selected one of the 5-point Likert scale items. Those who chose 5 (“Not working”) in the baseline survey or follow-up survey (n = 776) were excluded from the analysis. Therefore, “working status” was removed from the independent variables.

Discussion

We set out to determine the status of behavioral change in personal protective measures among ordinary Japanese citizens from the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak to the community transmission phase, in addition to the association between each sociodemographic factor and behavioral change. There were significant improvements in social distancing measures during the community transmission phase compared to the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak. However, the prevalence of avoiding touching the eyes, nose, and mouth was approximately 60%, indicating no significant improvement. Moreover, men and persons with low household income levels made fewer behavior changes for some personal protective measures when compared with women and persons with high household income levels. This study suggests that the implementation status of personal protective measures in ordinary citizens changes with each pandemic phase. This study also reveals that, while the implementation of personal protective measures had improved in the pandemic phase of COVID-19, there remains a potential for improvement, especially when it comes to avoiding touching eyes, nose and mouth, and among men and persons with low household income levels.

During the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak, the prevalence of social distancing measures and avoiding touching the eyes, nose, and mouth was approximately 60%; these measures had a much lower prevalence than other personal protective measures. However, in the community transmission phase, while there was a significant increase in the prevalence of social distancing measures, the prevalence of the latter measures remained almost unchanged. These differences may be due to differences in awareness of activities introduced by the Japanese government. From the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak, the adoption of measures by the Japanese government to cope with COVID-19 infection focused on identifying clusters of COVID-19 patients by tracing the route of transmission of patients with COVID-19. Among these measures, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare reported that clusters tended to occur in locations that satisfied three conditions:

-

(1)

Closed spaces with poor ventilation.

-

(2)

Crowded spaces with many people.

-

(3)

Conversations and vocalization in close proximity (within one arm’s length of one another).

Such locations included, for instance, athletic gyms and buffet-style meals (Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (JMHLW, 2020b). Based on this report, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare issued large-scale warnings to ordinary citizens to resist going to locations that satisfied these three conditions, in conjunction with educational activity about hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette (Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (JMHLW, 2020c). Additionally, on March 26, the governors of Tokyo and four neighboring prefectures issued a joint message urging people to avoid crowded places (Tokyo Metropolitan Government, 2020). The implementation of social distancing measures is thought to have vastly improved through these awareness activities. On the other hand, there were no large-scale awareness activities related to avoiding touching the eyes, nose, and mouth, which is assumed to be the reason for the lack of improvement in that behavior.

Moreover, face touching behavior is a common habit (Kwok et al., 2015); therefore, unless one is extremely careful, it may be difficult to stop. This study suggests that the implementation status of personal protective measures in ordinary citizens can change with each pandemic phase and awareness activities that are introduced. It may be important to monitor these changes for developing effective educational activities.

The multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that men and persons with low household income levels made fewer behavioral changes to adopt personal protective measures. It may be useful to focus on populations with such sociodemographic characteristics when providing education on personal protective measures during an infectious disease pandemic, which can lead to constraints on both time and resources. Previous studies on self-isolation have reported that people who are unable to work from home or lose income when absent from work have a lower rate of self-isolation (Blake et al., 2010, Eastwood et al., 2009). It may be essential to implement recommendations for working from home as well as salary compensation to enhance the prevalence of self-isolation, rather than merely executing awareness activities.

This study has some limitations that should be considered. The most crucial point is that participants in this study were recruited from people enrolled at a single internet research company; the results may have been affected by selection bias. Relatively little is known about the characteristics of people in online communities (Wright, 2017). The participants’ age and sex demographics were different from those of the general Japanese population (Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2019). Second, the results may only be directly applied to the Japanese people. In the case of other communities with different cultural, ethnic, and geographical backgrounds, the prevalence of personal protective measures and implementation status of behavioral changes may differ considerably when compared with those reported in the present survey. Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first study to clarify the behavioral changes in following personal protective measures among ordinary Japanese citizens from the early phase of COVID-19 in Japan to the community transmission phase and to identify an association between the behavior changes and each sociodemographic factor.

In conclusion, the implementation status of personal protective measures changed among ordinary citizens from the early epidemic phase of COVID-19 to the community transmission phase. The prevalence of many personal protective measures, including social distancing measures, by ordinary citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic improved, but left the potential for further improvement, especially in terms of avoiding touching eyes, nose, and mouth. Monitoring these changes may be relevant when considering practical educational activities to raise and promote awareness and adherence to preventive measures.

Funding source

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo, Japan (No: T2019-0234). Informed consent was obtained from all the respondents.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the participants who enrolled in this study.

References

- Betsch C., Wieler L.H., Habersaat K., COSMO group Monitoring behavioural insights related to COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1255–1256. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30729-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake K.D., Blendon R.J., Viswanath K. Employment and compliance with pandemic influenza mitigation recommendations. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(2):212–218. doi: 10.3201/eid1602.090638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood K., Durrheim D., Francis J.L., d’Espaignet E.T., Duncan S., Islam F. Knowledge about pandemic influenza and compliance with containment measures among Australians. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(8):588–594. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (JMHLW) 2020. About coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/newpage_00032.html [Google Scholar]

- Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (JMHLW) 2020. Expert Meeting on the Novel Coronavirus Disease Control Analysis of the Response to the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Recommendations (Excerpt)https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000611515.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (JMHLW) 2020. Preventing outbreaks of the novel coronavirus.https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10200000/000603320.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kwok Y.L., Gralton J., McLaws M.L. Face touching: a frequent habit that has implications for hand hygiene. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(2):112–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machida M., Nakamura I., Saito R., Nakaya T., Hanibuchi T., Takamiya T. Adoption of personal protective measures by ordinary citizens during the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet . 2020. Declaration of a state of emergency in response to the novel coronavirus disease.https://japan.kantei.go.jp/ongoingtopics/_00020.html [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Bureau of Japan . 2019. 2015 Population census.https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?page=1&toukei=00200521&tstat=000001080615 [Google Scholar]

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government . 2020. Joint message from the governors of Tokyo and four neighboring prefectures.https://www.seisakukikaku.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/information/0401message.html [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.CDC) 2020. How to protect yourself.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/prevention-treatment.html [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2020. Basic protective measures against the new coronavirus.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2020. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/ [Google Scholar]

- Wright K.B. Researching internet-based populations: advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2017;10(3) [Google Scholar]