Abstract

We reviewed all studies assessing the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) between 2009 and 2018 (n = 45). Most studies assessed HRQoL as an outcome, and evaluated or compared the HRQoL of HCC patients depending on the type of treatment or stage of disease. HCC patients had a worse HRQoL than the general population, including in those with early-stage HCC. Patients commonly experienced pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, distress, and lack of appetite, and these symptoms remained problematic even a few years after treatment. TNM classification of malignant tumors stage, tumor stage, presence of cirrhosis, being Asian, being female, living alone, or being unemployed were associated with a poor HRQoL. While recent studies have included a more diverse patient population, various topics, and different study designs, there were limited studies on supportive interventions. Given the increase in HCC cases and HCC survivors, addressing the HRQoL of HCC patients requires more attention.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Quality of life, Systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is defined as how well a person functions in their life and their perceived well-being in the physical, mental, and social domains of health (1). Recently, HRQoL has been considered a strong predictor of survival in cancer patients (2,3). In addition, understanding the impact of treatment on HRQoL could help physicians guide patients when deciding between two equally efficacious treatments (4,5). Furthermore, HRQoL is becoming a major factor for evaluating therapeutic interventions in patients with diseases that are difficult to cure to help patients remain symptom-free, or at least to reduce the disease burden (4,5).

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer (6,7). HCC patients have a high mortality rate, with the relative survival rates being 31.0% in 2013–2016 (8). HCC treatment is mainly palliative, unless the disease is in its early stage. HCC patients suffer from symptoms such as sleep disorders, sexual dysfunction, ascites, gynecomastia, pruritus, fatigue, and muscle cramps, in addition to a negatively affected HRQoL (9). According to the Korean Liver Cancer Association–National Cancer Center Korea Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma, the ultimate goal of treatment in HCC patients is to increase the survival time and rate, and to the improve HRQoL. This requires multidisciplinary treatment planning in various fields, including gastroenterology, hepatology, oncology, surgery, radiology, interventional radiology, radiation oncology, pathology, and many other departments (10). HRQoL can be affected by treatment of HCC.

During the past 10 years, there have been dramatic changes in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of HCC (11). Active surveillance was promoted among populations at risk of developing HCC, such as people with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infection, thus enabling early diagnosis (12). The emergence of multiple new treatment modalities has changed the HCC treatment paradigm (13). Local tumor-directed therapies have significantly improved, such as radio-frequency ablation (RFA) and novel agents for transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). Furthermore, there have been improvements in procedures such as hepatic resection and liver transplantation. In addition, sorafenib was approved in 2017 as the first effective systemic treatment for HCC. Positive sorafenib results in advanced HCC patients prompted the evaluation of several first- and second-line agents for the treatment of HCC (14). As numerous trial and observational studies have evaluated the effects of these new treatments (11), an increasing number of studies have assessed the HRQoL of HCC patients. In terms of systematic reviews focusing on the HRQoL of HCC patients, there were two review papers published between 1985 and 2013 (15,16). However, these papers did not include recent studies, which reflect new HCC management strategies. A recent narrative review included studies from 2001 to 2017, but it aimed to review measurement tools to assess HRQoL in HCC patients, and not the study design and outcomes related to HRQoL (17). Thus, this systematic review aims to evaluate studies assessing the HRQoL of HCC patients from 2009 to 2018.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Information Sources and Search

Two authors performed the 1st and 2nd literature screening. Studies were identified by searching electronic databases, scanning reference lists of articles, and consulting with experts in the field. Database searches were conducted using Cochrane Library, PsychINFO, Embase, and PubMed. First, we searched PubMed for all English-language studies that assessed the HRQoL of HCC patients, published between 2009 and 2018, using the following terms: 1) hepatocellular carcinoma: “Carcinomas, Hepatocellular” OR “Hepatocellular Carcinomas” OR “Liver Cell Carcinoma, Adult” OR “Liver Cancer, Adult” OR “Adult Liver Cancer” OR “Adult Liver Cancers” OR “Cancer, Adult Liver” OR “Cancers, Adult Liver” OR “Liver Cancers, Adult” OR “Liver Cell Carcinoma” OR “Carcinoma, Liver Cell” OR “Carcinomas, Liver Cell” OR “Cell Carcinoma, Liver” OR “Cell Carcinomas, Liver” OR “Liver Cell Carcinomas” OR “Hepatocellular Carcinoma” OR “Hepatoma” OR “Hepatomas”, and 2) quality of life: “Life Quality” OR “Health-Related Quality Of Life” OR “Health Related Quality Of Life” OR “HRQOL”. We then used the same terms to conduct cross-validation searches with Cochrane Library, PsychINFO, and Embase.

Inclusion Criteria and Study Selection

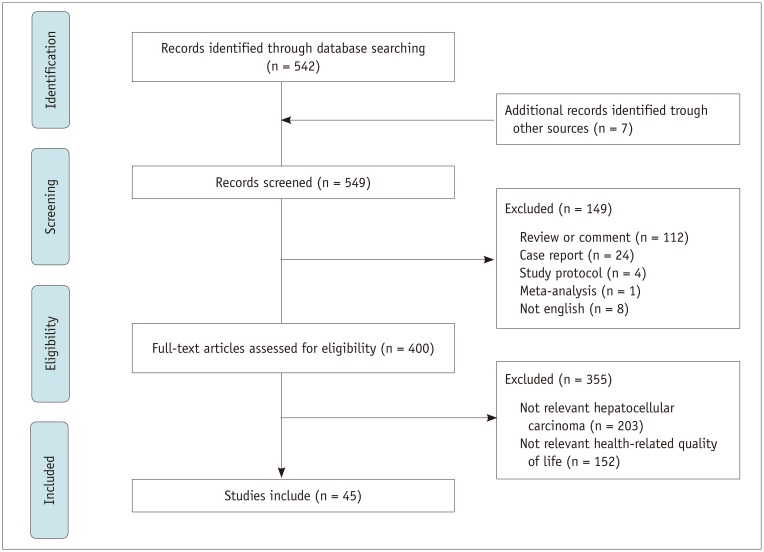

All observational and interventional studies were included if they included HRQoL results, either as an exposure or an outcome. Studies were also included if they included HRQoL as a secondary outcome. Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) a literature review, commentary, or case study article; 2) studies with samples including children or adolescents only; 3) studies with samples involving heterogeneous populations diagnosed with other cancers or other liver disease; and 4) studies reporting findings not directly relevant to the core concept of HRQoL (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Flow diagram of study selection.

Data Collection Process

We developed a data extraction sheet, performed a pilot-tested using five randomly selected studies from our search results, and refined it accordingly. Two review authors independently extracted data from the included studies and then discussed the results. Disagreements were resolved by discussion until a consensus was reached between the two review authors. We extracted the data depending on whether HRQoL was measured as an exposure or an outcome. If no agreement could be reached, a senior author (JC) would final decision. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement as a guide to ensure that current standards for systematic review methodology were met (18).

Data Items

The following information and data were extracted from each included study: 1) purpose of assessing HRQoL (exposure or outcome); 2) study design (cross-sectional, cohort, or interventional) and methods (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed); 3) characteristics of the study such as nation, author, year of publication, year the study began, and tool used to measure HRQoL; 4) characteristics of participants such as number of participants included, mean age, mean survival at enrollment, stage, liver function, and patient treatment status at enrollment; and 5) summary of main results. Since studies assessing the HRQoL in HCC patients were heterogeneous in purpose and methodology, we did not use summary measures such as risk ratio or difference in means.

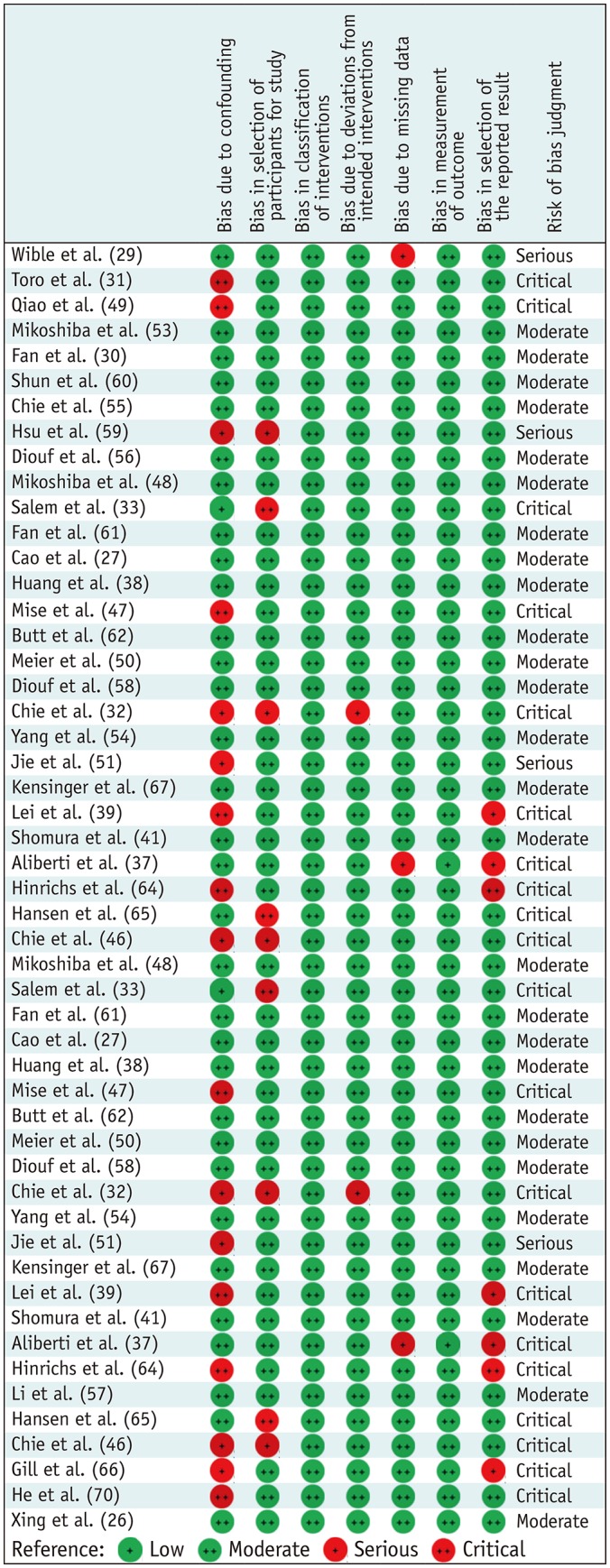

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

If the study was not a randomized controlled trial, we evaluated the risk of bias in individual studies among those that used HRQoL as primary exposure or outcome. To evaluate the risk of bias, we used Risk of Bias in Nonrandomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I). This tool can be used to evaluate the effects of exposure on observational studies—such as cohort studies and case control studies—in which exposed groups are allocated during the course of normal treatment decisions, and quasi-randomized studies in which the method of allocation falls short of full randomization (19). ROBINS-I detected bias due to confounders, bias in participant selection, bias in classifying interventions (or exposure), bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing data, bias in measuring outcomes, bias in selecting reported results, and overall risk of bias. We classified risk of bias as low, moderate, serious, critical risk of bias, and no information.

To explore variability in study results (heterogeneity), we specified the following hypotheses before conducting the analysis. We hypothesized that the effect size might differ according to the methodological quality of studies. We did not evaluate risk of bias across studies due to heterogeneous study objectives.

RESULTS

Study Selection

In our PubMed search, we found 542 relevant studies conducted during the study period (2009–2018). When we performed a search using the same research terms in Embase, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library, we found 7 additional articles, resulting in 549 studies. We excluded 149 studies due to their study design (Fig. 1). Reviews or comments (n = 112), case reports (n = 24), study protocols (n = 4), and meta-analysis (n = 1) were also excluded. An additional eight papers were excluded as they were written in other languages. Next, we reviewed the remaining 400 eligible studies and excluded 355 that were not relevant to HCC (n = 203) or HRQoL (n = 152), resulting in 45 studies which met the inclusion criteria.

Study Characteristics

Among the 45 studies, HRQoL was assessed as an outcome in 40 studies (Table 1) and as an exposure in 5 studies (Table 2). USA (n = 10, 23%) and China (n = 10, 23%) conducted the largest number of HRQoL studies, followed by Japan (n = 5, 12%) and France (n = 4, 9%). Seven (16%) studies were multinational. The mean duration since enrolling patients or collecting data to publish the manuscript was 7.3 years (standard deviation = 3.6 years).

Table 1. Summary of Studies that Used HRQoL as Outcomes (n = 40).

| Study | Year | Nation | Study Design | n | Mean Age (Median) | Severity | Child-Pugh Score | Status at Enrollment | Type of Treatment | Intervention or Treatment | QoL Questionnaire |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures of HRQoL in HCC patient (n = 16) | |||||||||||

| Wible et al. (29) | 2010 | USA | Cohort | 73 | 62 | All stage | A 34 | At diagnosis | TACE | SF-36 | |

| B 37 | |||||||||||

| C 2 | |||||||||||

| Qiao et al. (49) | 2012 | China | Cross sectional | 140 | 52 | All stage | A 84 | At diagnosis | No treatment | FACT-Hep | |

| B 29 | |||||||||||

| C 27 | |||||||||||

| Hsu et al. (59) | 2012 | Taiwan | Cross sectional | 300 | 62 | All stage | A 202 | All | Combined | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| B 88 | |||||||||||

| C 10 | |||||||||||

| Shun et al. (60) | 2012 | Taiwan | Cohort | 89 | 61 | All stage | A 41 | After treatment | TACE | SF-12, SDS, HADS | |

| B 42 | |||||||||||

| C 6 | |||||||||||

| Fan and Eiser (30) | 2012 | Taiwan | Cross sectional | 33 | 54 | All stage | Unknown | After treatment | Resection, TAE/TACE, Chemotherapy | Interview | |

| Cao et al. (27) | 2013 | China | Cross sectional | 155 | 53 | All stage | A 146 | After treatment | TACE | MDASI and SCL | |

| B 9 | |||||||||||

| Fan et al. (61) | 2013 | Taiwan | Cross sectional | 286 | 60 | All stage | A 224 | After treatment | Resection, TAE/TACE, chemo | EORTC QLQ-C30, Brief IPQ, Jalowiec Coping Scale | |

| B 42 | |||||||||||

| C 16 | |||||||||||

| Missing 4 | |||||||||||

| Kaiser et al. (28) | 2014 | USA | Cross sectional | 10 | 58 | Advancedstage | Not mention | All | Systemic therapy | Pain (FACT), EORTC QLQHCC18, and interview | |

| Butt et al. (62) | 2014 | USA | Cohort | 83 | 64 | All stage | Mean = 6.1 (1.3) | After treatment | Combined | FACT-Hep, BPI, Interference Scale | |

| Mise et al. (47) | 2014 | Japan | Cohort | 69 | 69 | All stage | Unknown | At diagnosis | Resection | SF-36 | |

| Phillips et al. (63) | 2015 | Multi | Cohort | 167 | 56 | Advancedstage | A 86 | At diagnosis | No treatment | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| B 69 | |||||||||||

| C 24 | |||||||||||

| Lei et al. (39) | 2016 | China | Cohort | 207 | 47 | Early-stage | Unknown | After treatment | Resection or LT | SF-36, SCL-90-R | |

| Hinrichs et al. (64) | 2017 | Germany | Cohort | 79 | 66 | Advancedstage | A 60 | At diagnosis | TACE | EORTC QLQ -C30, HCC18 | |

| B 19 | |||||||||||

| Hansen et al. (65) | 2017 | USA | Cross sectional | 18 | 63 | Advancedstage | Unknown | After treatment | Sorafenib, TACE or radiation | MSAS | |

| Chie et al. (46) | 2017 | France | Cross sectional | 227 | 61 | All stage | A 180 | After treatment | Resection, RFA, TACE, or systemic treatment | EORTC QLQ-C30, HCC18 | |

| B 40 | |||||||||||

| C 7 | |||||||||||

| Gill et al. (66) | 2018 | Multi | Cross sectional | 256 | -64 | All stage | Unknown | After treatment | Combined | Side Effects and QoL (developed) | |

| Treatment efficacy on HRQoL (n = 17) | |||||||||||

| Kuroda et al. (45) | 2010 | Japan | Intervention | 35 | 66 | All stage | A 14 | After treatment | RFA | BCAA | SF-8 |

| B 19 | |||||||||||

| C 2 | |||||||||||

| Tian et al. (42) | 2010 | China | Intervention | 97 | 52 | Advancedstage | A 70 | During treatment | Unknown | Chinese medicine therapy | Pain with VAS, Karnofsky's Scores |

| B 27 | |||||||||||

| Chow et al. (44) | 2011 | Multi | Intervention | 185 | 58 | Advancedstage | A 86 | At diagnosis | No treatment | MA (320 mg day) | EORTC QLQ-C30 |

| B 69 | |||||||||||

| C 24 | |||||||||||

| Toro et al. (31) | 2012 | Italy | Cohort | 51 | 70 | All stage | A 28 | At diagnosis | No treatment | Resection, TACE and RFA | FACT-G |

| B 23 | |||||||||||

| Salem et al. (33) | 2013 | USA | Cohort | 56 | 67 | Advancedstage | A 48 | At diagnosis | No treatment | TACE and 90Y radioembolization | FACT-Hep |

| B 8 | |||||||||||

| Meyer et al. (34) | 2013 | UK | Intervention | 86 | 63 | Advancedstage | A 71 | At diagnosis | No treatment | TACE and TAE | EORTC QLQ -C30, HCC18, CTCAE |

| B 15 | |||||||||||

| Huang et al. (38) | 2014 | China | Cohort | 348 | 51 | Early-stage | A 348 | After treatment | TAE | Resection and RFA | FACT-Hep |

| Kolligs et al. (35) | 2015 | Multi | Intervention | 28 | 66 | Moderate/late stage | A 25 | At diagnosis | Unknown | SIRT and TACE | FACT-Hep, CTCAE |

| B 3 | |||||||||||

| Xing et al. (26) | 2015 | USA | Cohort | 118 | 60 | Advancedstage | A 66 | At diagnosis | No treatment | DEB-TACE | SF-36 |

| B 46 | |||||||||||

| C 6 | |||||||||||

| Chie et al. (32) | 2015 | Multi | Cohort | 171 | 62 | All stage | A 135 | At diagnosis | Combined | Resection, RFA, or TACE | EORTC QLQ-C30, HCC18 |

| missing 36 | |||||||||||

| Anota et al. (36) | 2016 | France | Intervention | 21 | 64 | All stage | A 16 | At diagnosis | Unknown | DEB-TACE (5/10/15 mg) | EORTC QLQ-C30, CTCAE |

| B 5 | |||||||||||

| Kensinger et al. (67) | 2016 | USA | Cohort | 502 | 54 | All stage | Unknown | All | Unknown | LT | SF-36, BAI, CES-D |

| Lv et al. (43) | 2016 | China | Intervention | 120 | 52 | Advancedstage | A 73 | At diagnosis | Unknown | TACE with Parecoxib sodium | CTCAE, Pain Score (NRS), Self Developed QoL Items |

| B 47 | |||||||||||

| Qiu et al. (68) | 2017 | China | Intervention | 91 | 65 | Advancedstage | A 17 | After treatment | TACE, RFA, TACE + RFA, Sorafenib | TIPS in PVTT patients | Karnofsky's Scores |

| B 39 | |||||||||||

| C 35 | |||||||||||

| Aliberti et al. (37) | 2017 | Italy | Cohort | 42 | 65 | Advancedstage | A 31 | After treatment | Resection, RFA, or chemotherapy | TACE and PEG embolics | Palliative Performance Scale, CTCAE |

| B 11 | |||||||||||

| Chau et al. (69) | 2017 | Multi | Intervention | 565 | 62 | Advancedstage | A(5/6) 553 | After treatment | Sorafenib therapy | Ramucirumab 8 mg/kg | FHSI-8 and EuroQoL-5D |

| 7 point = 12 | |||||||||||

| He et al. (70) | 2018 | China | Cohort | 128 | 46 | Early-stage | A 84 | After treatment | Resection, RFA, or LT | SF-36 | |

| B 35 | |||||||||||

| C 9 | |||||||||||

| QoL and its associated factors (n = 4) | |||||||||||

| Mikoshiba et al. (48) | 2013 | Japan | Cross sectional | 128 | 69 | All stage | A 96 | After treatment | Unknown | EORTC QLQ-C30, HCC18, CES-D | |

| B/C 32 | |||||||||||

| Hansen et al. (52) | 2015 | USA | Cohort | 45 | 62 | Advancedstage | Unknown | After treatment | Any treatment | Interview | |

| Shomura et al. (41) | 2016 | Japan | Cohort | 54 | (71) Advancedstage | Advancedstage | Score of 5 = 33, Higher than 5 point = 27 | After treatment | Sorafenib | SF-36 | |

| Jie et al. (51) | 2016 | China | Cohort | 218 | 50 | All stage | Unknown | At diagnosis | Unknown | Resection or RFA | EORTC QLQ-C30, Brief IPQ |

| Validation (n = 3) | |||||||||||

| Mikoshiba et al. (53) | 2012 | Japan | Cross sectional | 192 | 68 | All stage | A 127 | All | Combined | EORTC QLQ-C30, QLQ-HCC18 | |

| B 53 | |||||||||||

| C 12 | |||||||||||

| Chie et al. (55) | 2012 | Multi | Cross sectional | 227 | 61 | All stage | A 180 | After treatment | Combined | EORTC QLQ -C30, EORTC QLQ -HCC18 | |

| B 38 | |||||||||||

| C 2 | |||||||||||

| Yang et al. (54) | 2015 | China | Cross sectional | 114 | 51 | All stage | Unknown | All | Resection or others | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory, BCAA = branched-chain amino acid-enriched nutrient, BPI = Brief Pain Inventory, CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, CTCAE = Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, DEB = doxorubicin drug-eluting bead, EORTC = European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, EORTC QLQ-C30 = EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30, FACT = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy, FACT-G = FACT-General, FACT-Hep = FACT-Hepatobiliary, FHSI-8 = FACT Hepatobiliary Symptom Indexes, HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, HRQoL = Health-Related QoL, IPQ = Illness Perception Questionnaire, LT = liver transplantation, MA = megestrol acetate, MDASI = M. D. Anderson Symptom Inventory, MSAS = Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale, NRS = Numeral Rating Scale, PEG = polyethylene glycol, PVTT = portal vein tumor thrombus, QoL = quality of life, RFA = radio-frequency ablation, SCL = symptom checklist, SDS = Symptom Distress Scale, SF = short form, SIRT = selective internal radiation therapy, TACE = transarterial chemoembolization, TAE = transarterial embolization, TIPS = transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, VAS = visual analogue scale

Table 2. Summary of Studies that Used HRQoL as Exposure (n = 5).

| Author | Year | Nation | Study Design | n | Mean Age (Median) | Time at Enroll | Severity | Child-Pugh Score | QoL Measurement | Number of QoL Assessments | Primary Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diouf et al. (56) | 2013 | France | Cohort | 271 | 67 | At diagnosis | Late-stage | A 182 | EORTC QLQ-C30 | 1 | OS |

| B 64 | |||||||||||

| C 2 | |||||||||||

| D 23 | |||||||||||

| Diouf et al. (58) | 2015 | France | Cohort | 271 | 67 | At diagnosis | Late-stage | A 182 | EORTC QLQ-C30 | 1 | OS |

| B 64 | |||||||||||

| C 2 | |||||||||||

| D 23 | |||||||||||

| Meier et al. (50) | 2015 | USA | Cohort | 130 | 57 | At diagnosis | All | A 56 | EORTC QLQ-C30, HCC18 | 1 | OS |

| B 45 | |||||||||||

| C 29 | |||||||||||

| Li et al. (57) | 2017 | Hong Kong | Cohort | 472 | (60) | After treatment | Hetero | A 319 | EORTC QLQ-C30, HCC18 | 1 | OS |

| B 130 | |||||||||||

| C 23 | |||||||||||

| Xing et al. (71) | 2018 | USA | Cohort | 30 | 62 | At diagnosis | Late-stage | A 20 | SF-36 | 4 | OS |

| B 10 |

OS = overall survival

Most studies assessed HRQoL using quantitative methods (n = 42, 93%), with only three using qualitative methods. There were 23 (51%), 13 (29%), and 9 (20%) cohort, cross-sectional, and interventional studies, respectively. With cohort and interventional studies, the median follow-up time was 21 months, and on average, HRQoL was assessed three times during the follow-up.

Among 23 cohort studies, 8 (35%) evaluated the effects of specific HCC treatments on HRQoL, and 7 (30%) evaluated the HRQoL of HCC patients over time. Three cohort studies aimed to identify factors associated with HRQoL (13%), and five cohort studies evaluated the impact of HRQoL on the clinical outcome (22%). Among the 14 cross-sectional studies, 9 evaluated the HRQoL at a certain point in time, and 3 were tool validation studies. All intervention studies (n = 9) evaluated the effect of treatment on HRQoL.

HRQoL Measurements

Eight studies used the short form (SF)-36, which is a general measurement tool for assessing HRQoL (20). Half of the studies (n = 25, 56%) used cancer specific HRQoL questionnaires. The most frequently used questionnaire was the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30) (n = 17) (21), followed by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) (n = 6) (22). In addition, 38 studies used additional liver cancer-specific questionnaires. The most frequently used liver cancer-specific questionnaires were the EORTC-hepatocellular carcinoma 18 (HCC18) (23) and the FACT-Hepatobiliary (FACT-Hep) questionnaires (24). One study used the FACT Hepatobiliary Symptom Index-8 (FHSI-8), which is an eight-item subset of FACT-Hep, to assess specific symptoms of hepatobiliary carcinoma (25).

Participants

The median sample size was 154 (range, 15–565) participants, and the median age of the study participants was 58.9 years. In total, 18 (40%), 19 (42%), and one (2%) studies were conducted with patients before (at diagnosis), after, and during HCC treatment, respectively. Seven (16%) studies recruited patients at different treatment stages. While 18 studies (40%) assessed the HRQoL of late-stage HCC patients, only 3 studies evaluated the HRQoL of early-stage HCC patients. Similarly, 19 (42%) and 14 studies (31%) were conducted in patients who had a Child-Pugh score of more than C, and A, or B, respectively.

HRQoL as Outcomes

Among 40 studies, which assessed HRQoL as an outcome (Table 1), 16 studies evaluated the HRQoL of HCC patients, and of those, 8 focused on TACE patients and four on resection patients. According to SF-36 scores, when compared to the age-adjusted healthy US population, patients with HCC prior to initiation had lower general health (38.2 vs. 70.1), mental health (45.2 vs. 75.2), physical functioning (36.2 vs. 83.0), role–emotional (37.7 vs. 77.9), role–physical (37.7 vs. 77.9), social functioning (38.7 vs. 83.6), and vitality (42.1 vs. 57.0) (26). Patients commonly reported abdominal pain, nausea, jaundice, weight loss, and body image issues. Among late stage HCC patients, the most severe symptoms at diagnosis were fatigue and distress (27), and 90% of patients reported pain during and after treatment (28). The abdomen and lower back were the most common sites of pain (28). Fatigue was the most serious symptom followed by sleep disturbance, distress, sadness, and lack of appetite even after treatment (27). Symptoms of upper gastrointestinal distress and liver function impairment also remained after treatment (27). However, patients exhibited improved mental health scores after the treatment compared to before treatment (29). According to the results of a qualitative study, patients perceived HCC as a long-term and chronic disease that, while incurable, might be controllable. Control measures included focusing on managing HCC and its symptoms, managing emotional responses, and leading a normal life (30).

HRQoL in Patients Treated with TACE

Seventeen studies compared the effects of treatment methods on the HRQoL. Among them, 7 studies evaluated the HRQoL of TACE patients, and other studies compared the HRQoL of TACE patients to those treated with RFA or resection (n = 2) (31,32), 90Y therapy, (n = 1) (33), transarterial embolization (n = 1) (34), and/or selective internal radiation therapy (n = 1) (35). Three studies assessed HRQoL by different methods or dose of TACE: doxorubicin drug eluting bead (DEB)-TACE therapies (n = 2) (26), maximum tolerated dose of TACE (n = 1) (36), or TACE using loaded polyethylene glycol (PEG) drug-elutable microspheres (n = 1) (37). Patients treated with TACE had lower baseline scores in all eight HRQoL domains of the SF-36 compared to the US age-adjusted healthy normal participants. The HRQoL post therapy and at 6 or 12 months after completion of TACE did not differ between patients receiving ≥ 4 vs. ≤ 3 DEB-TACE (p > 0.05) (26). Prior to TACE treatment, the 5 most severe symptoms ranked in order were fatigue, distress, sadness, sleep disturbance, and lack of appetite (27). After TACE, fatigue was still the most bothersome symptom, followed by sleep disturbance, distress, sadness, and lack of appetite (27). After TACE, while bodily pain scores improved, vitality scores worsened, which is associated with fatigue (29). Mental health scores improved after 4 months of TACE. However, at 12 and 24 months after treatment, patients continued reporting decreased physical (12 months: −34.29, 24 months: −40.99), social/family (12 months: −35.32, 24 months: −42.27), emotional (12 months: −28.06, 24 months: −37.35), and functional (12 months: −43.07, 24 months: −53.61) well-being (31).

HRQoL in Patients Treated by Resection

The HRQoL of resection patients was compared to that of patients treated with RFA (n = 2) (32,38), transplantation. (n = 1) (39), or both (n = 1) (40). Patients with liver transplantation or resection had a relatively better HRQoL compared to patients with other treatments (39). After hepatic resection, HRQoL first declined, but then increased to preoperative levels at 6 months after surgery, and slightly improved than preoperative levels at 12 months after surgery (38). Physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well-being of patients treated by hepatic resection were significantly better than for all other treatments at 24 months after resection (31).

HRQoL in Patients Treated with RFA

According to FACT scores, physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well-being declined following RFA treatment, and did not recover to preoperative levels at 24 months after surgery (31). Additionally at 24 months after surgery, changes in physical (RFA: −18.81, surgery: 7.37), social/family (RFA: −24.29, surgery: 7.13), emotional (RFA: −29.98, surgery: 6.73), and functional (RFA: −18.35, surgery: 6.05) well-being before and after RFA treatment were poorer than that of surgery patients (31). However, RFA patients had less bodily pain (RFA: 87.9 vs. transplantation: 80.2 vs. surgery: 80.5, p = 0.01) and more vitality (RFA: 81.9 vs. transplantation: 72.4 vs. surgery: 73.4, p < 0.01) than patients with transplantation or resection at 3 years after treatment (40). Patients treated with RFA reported better physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well-being at 24 months after treatment than patients treated with TACE (31).

HRQoL in Patients Treated with Targeted Therapy (Sorafenib)

Patients receiving sorafenib experienced hand-foot skin reactions, diarrhea, or weight loss. Sorafenib use was associated with deterioration of liver function, and the progressive nature of the disease limited the efficacy of sorafenib. During treatment, symptoms did not improve, and patients experienced decreased physical functioning and vitality over time (41).

Effects of Supportive Care Intervention on the HRQoL

Four studies evaluated the effects of supportive care/intervention on the HRQoL, and all studies were conducted with inoperative or advanced stage HCC patients. Chinese medicine comprehensive therapy (42) and perioperative parecoxib sodium (43) were used for pain relief, and megestrol acetate (MA) (44) and branched-chain amino acid (BCAA)-enriched nutrients (45) were used for nutrition support. Chinese medicine and perioperative parecoxib sodium improved pain scores. Supplementation with BCAA-enriched nutrients for one year showed improved nutrition and HRQoL among patients with inoperable HCC undergoing TACE (45). MA helped alleviate appetite loss and nausea/vomiting in patients with treatment-naïve advanced HCC compared to patients without MA, but demonstrated no role in prolonging overall survival (44).

Factors Associated with HRQoL

Four studies were conducted to identify factors that affected HRQoL among HCC patients. In terms of patient characteristics, being Asian (46), being female (47), living alone (48), and unemployment (48) were associated with poor HRQoL. Regarding clinical characteristics, severe TNM stage (49), Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer tumor stage (50), and cirrhosis were associated with poor HRQoL. Other physical (fatigue, sleep disturbance, and lack of appetite) (27) and emotional symptoms (distress, sadness, and depression) were significantly associated with poor HRQoL (27,48). In terms of social function, disclosure of cancer (51) and lack of information were related to worse HRQoL (52). In addition, illness perceptions and personal control of the patients' own disease were positively correlated with HRQoL (51).

HRQoL Tool Validation Studies

Three Japanese- and Chinese-language studies were conducted to validate the EORTC QLQ-HCC18. Besides two validation studies for the Japanese (53) and Chinese EORTC QLQ-HCC18 (54), one study was conducted for cross-cultural validation (55). Cronbach's α was used to measure internal consistency, showing a value greater than 0.60 in the Japanese and Chinese EORTC QLQ-HCC18. In the international field validation study, researchers found that there were low or moderate correlations between the QLQ-HCC18 and QLQ-C30. As a result, they recommended the use of EORTC QLQ-HCC18 as a supplementary module for the EORTC QLQ-C30 in clinical trials for patients with HCC.

HRQoL as an Exposure

Five studies measured HRQoL as an exposure (Table 2). Poor HRQoL is an independent prognostic factor of all-cause mortality in palliative HCC patients (56). In addition, experiencing pain, fatigue, poor physical functioning (57), and poor role functioning (50) were shown to be independent factors associated with mortality. Based on the EORTC QLQ-C30, 50 points out of 100 was the optimal cutoff value to predict mortality among HCC patients for global health, 58.3 for physical functioning, 66.7 for role functioning, 66.7 for fatigue, and 33.33 for diarrhea (58).

Risk of Bias

Among studies primarily designed to measure HRQoL, 15 showed a moderate risk of bias, 13 showed a critical risk, and 3 showed a serious risk (Fig. 2). Confounding factors were identified as the most frequent critical or serious risk (11/31). Almost 30% of studies did not control for confounding factors (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Evaluated risk of bias for non-randomized controlled trial study with health-related quality of life as primary exposure or outcome (n = 31).

DISCUSSION

This review summarized 45 studies measuring the HRQoL of HCC patients, published between 2009 and 2018. During this period, USA and China conducted the largest number of HRQoL studies, followed by Japan and France. Approximately half of the studies were cohort studies, and one-fifth were intervention studies. In the cohort and interventional studies, the median follow-up time was 21 months, and on average, HRQoL was assessed three times during follow-up. Most studies assessed HRQoL as an outcome and evaluated or compared the HRQoL of HCC patients depending on type of treatment or stage of disease. HCC patients had a worse HRQoL than the general population, including those with early-stage HCC. Patients commonly experienced pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, distress, and lack of appetite, and these symptoms remained problematic even a few years after treatment. TNM stage, tumor stage, presence of cirrhosis, being Asian, being female, living alone, or being unemployed were associated with poor HRQoL. Additional physical and emotional symptoms were associated with poor HRQoL, and poor HRQoL was an independent prognostic factor of all-cause mortality among advanced stage HCC patients. Despite this significance, only four interventional studies tried to improve the HRQoL in HCC patients.

This review is consistent with previous reviews (15,16,17) which showed that HCC patients (including early-stage) have a worse HRQoL in terms of physical function, emotional status, and functional ability than the general population. HCC patients commonly experienced fatigue, sleep disturbance, distress, sadness, and lack of appetite regardless of disease stage or course of treatment. In terms of liver specific problems, patients reported abdominal pain, nausea, jaundice, weight loss, and body image issues. In general, after treatment completion, the HRQoL of HCC patients improved over time, though results varied based on treatment type and stage at diagnosis. For example, the HRQoL of patients who underwent resection improved over time (comparable to levels before treatment), but the HRQoL of patients treated with TACE did not improve, even several years after treatment completion. While there were a limited number of studies directly comparing HRQoL by treatment method, patients treated by resection/surgery or RFA (with small size tumor) seemed to have a better HRQoL than patients treated with TACE. This might be because patients with early stage HCC were more likely to receive surgery or RFA rather than TACE, and patients with TACE likely had a worse HRQoL at diagnosis compared to patients treated with other methods.

According to previous reviews, few studies focused on assessing the HRQoL of HCC patients and most were conducted in a palliative setting (16). However, in our analysis, we found an increasing number of studies evaluating HRQoL of HCC patients, including several conducted with early or intermittent stage patients. Additionally, studies evaluated and compared HRQoL based on new treatment modalities such as RFA, TACE, and sorafenib. We found that RFA patients had decreasing social/family, emotional, and long-term physical well-being. TACE patients had a worse HRQoL during and after treatment compared to RFA patients. While some studies evaluated the HRQoL 2 or 3 years after treatment, a limited number included long-term survivors, and no study primarily focused on this group. This might be due to the relatively high mortality in liver cancer patients, with health professionals focusing more on the HRQoL of patients under active treatment rather than long-term survivors. Lastly, our review included qualitative studies, which indicated that patients perceived HCC as a long-term difficulty, with challenges that include symptom management, emotional response management, and generally trying to lead a normal life.

Several limitations of this review should be acknowledged. First, we specifically focused on studies conducted with HCC-only patients; we neglected studies that included subjects with metastasis or those diagnosed with other types of liver cancer. Secondly, because we found HRQoL studies using the search term ‘quality of life,’ we might have missed studies using other terminology or expressions. However, we attempted to identify articles using key words similar to the MeSH terms. Thirdly, since the purpose of this review was to analyze all types of studies on HRQoL, studies included in this review were heterogeneous in purpose and design, and we were unable to conduct a quantitative review. Furthermore, we evaluated the quality of the reviewed studies by identifying potential bias.

In summary, from 2009 to 2018, an increasing number of studies evaluated the HRQoL of HCC patients, with studies becoming more diverse by covering a wider patient population (patients at different stage of disease), various topics (different treatment effects on HRQoL, effect of HRQoL on survivorship and psychosocial well-being), and different study designs (cohort and interventions). Regardless of stage at diagnosis or treatment method, HCC patients experienced various physical and psychosocial symptoms resulting in poor HRQoL and worse progression of the disease, yet there were limited supportive interventions. Given the increase in HCC cases and HCC survivors, more attention is needed to evaluate and improve the HRQoL of HCC patients.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Hays RD, Reeve BB. Measurement and modeling of healthrelated. In: Kellewo J, Heggenhougen HK, Quah SR, editors. Epidemiology and demography in public health. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siddiqui F, Pajak TF, Watkins-Bruner D, Konski AA, Coyne JC, Gwede CK, et al. Pretreatment quality of life predicts for locoregional control in head and neck cancer patients: a radiation therapy oncology group analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Movsas B, Moughan J, Sarna L, Langer C, Werner-Wasik M, Nicolaou N, et al. Quality of life supersedes the classic prognosticators for long-term survival in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: an analysis of RTOG 9801. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5816–5822. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.7420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langendijk JA, Doornaert P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Leemans CR, Aaronson NK, Slotman BJ. Impact of late treatment-related toxicity on quality of life among patients with head and neck cancer treated with radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3770–3776. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siddiqui F, Liu AK, Watkins-Bruner D, Movsas B. Patient-reported outcomes and survivorship in radiation oncology: overcoming the cons. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2920–2927. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.0707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HS, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in the USA. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2019;21:17. doi: 10.1007/s11894-019-0681-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon SK, Chun HG. Status of hepatocellular carcinoma in South Korea. Chin Clin Oncol. 2013;2:39. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3865.2013.11.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Toni EN, Schlesinger-Raab A, Fuchs M, Schepp W, Ehmer U, Geisler F, et al. Age independent survival benefit for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) without metastases at diagnosis: a population-based study. Gut. 2020;69:168–176. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-318193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun VC, Sarna L. Symptom management in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:759–766. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.759-766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korean Liver Cancer Association; National Cancer Center. 2018 Korean Liver Cancer Association–National Cancer Center Korea practice guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Radiol. 2019;20:1042–1113. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2019.0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah C, Mramba LK, Bishnoi R, Bejjanki H, Chhatrala HS, Chandana SR. Survival differences among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma based on the stage of disease and therapy received: pre and post sorafenib era. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2017;8:789–798. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2017.06.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singal AG, Pillai A, Tiro J. Early detection, curative treatment, and survival rates for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Lope CR, Tremosini S, Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Management of HCC. J Hepatol. 2012;56 Suppl 1:S75–S87. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(12)60009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koeberle D, Dufour JF, Demeter G, Li Q, Ribi K, Samaras P, et al. Sorafenib with or without everolimus in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): a randomized multicenter, multinational phase II trial (SAKK 77/08 and SASL 29) Ann Oncol. 2016;27:856–861. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan SY, Eiser C, Ho MC. Health-related quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:559–564. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandhi S, Khubchandani S, Iyer R. Quality of life and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;5:296–317. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2014.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Yeo W. Value of quality of life analysis in liver cancer: a clinician's perspective. World J Hepatol. 2017;9:867–883. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i20.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savovic´ J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blazeby JM, Currie E, Zee BC, Chie WC, Poon RT, Garden OJ. Development of a questionnaire module to supplement the EORTC QLQ-C30 to assess quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, the EORTC QLQ-HCC18. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2439–2444. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heffernan N, Cella D, Webster K, Odom L, Martone M, Passik S, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in patients with hepatobiliary cancers: the functional assessment of cancer therapy-hepatobiliary questionnaire. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2229–2239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yount S, Cella D, Webster K, Heffernan N, Chang C, Odom L, et al. Assessment of patient-reported clinical outcome in pancreatic and other hepatobiliary cancers: the FACT Hepatobiliary Symptom Index. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:32–44. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00422-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xing M, Webber G, Prajapati HJ, Chen Z, El-Rayes B, Spivey JR, et al. Preservation of quality of life with doxorubicin drug-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: longitudinal prospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1167–1174. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao W, Li J, Hu C, Shen J, Liu X, Xu Y, et al. Symptom clusters and symptom interference of HCC patients undergoing TACE: a cross-sectional study in China. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:475–483. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaiser K, Mallick R, Butt Z, Mulcahy MF, Benson AB, Cella D. Important and relevant symptoms including pain concerns in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): a patient interview study. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:919–926. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wible BC, Rilling WS, Drescher P, Hieb RA, Saeian K, Frangakis C, et al. Longitudinal quality of life assessment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after primary transarterial chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:1024–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan SY, Eiser C. Illness experience in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: an interpretative phenomenological analysis study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:203–208. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834ec184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toro A, Pulvirenti E, Palermo F, Di Carlo I. Health-related quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation or no treatment. Surg Oncol. 2012;21:e23–e30. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chie WC, Yu F, Li M, Baccaglini L, Blazeby JM, Hsiao CF, et al. Quality of life changes in patients undergoing treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:2499–2506. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0985-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salem R, Gilbertsen M, Butt Z, Memon K, Vouche M, Hickey R, et al. Increased quality of life among hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with radioembolization, compared with chemoembolization. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1358–1365.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer T, Kirkwood A, Roughton M, Beare S, Tsochatzis E, Yu D, et al. A randomised phase II/III trial of 3-weekly cisplatin-based sequential transarterial chemoembolisation vs embolisation alone for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1252–1259. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kolligs FT, Bilbao JI, Jakobs T, Iñarrairaegui M, Nagel JM, Rodriguez M, et al. Pilot randomized trial of selective internal radiation therapy vs. chemoembolization in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2015;35:1715–1721. doi: 10.1111/liv.12750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anota A, Boulin M, Dabakuyo-Yonli S, Hillon P, Cercueil JP, Minello A, et al. An explorative study to assess the association between health-related quality of life and the recommended phase II dose in a phase I trial: idarubicin-loaded beads for chemoembolisation of hepatocellular carcinoma. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010696. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aliberti C, Carandina R, Sarti D, Mulazzani L, Pizzirani E, Guadagni S, et al. Chemoembolization adopting polyethylene glycol drug-eluting embolics loaded with doxorubicin for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;209:430–434. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.17477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang G, Chen X, Lau WY, Shen F, Wang RY, Yuan SX, et al. Quality of life after surgical resection compared with radiofrequency ablation for small hepatocellular carcinomas. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1006–1015. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lei JY, Yan LN, Wang WT, Zhu JQ, Li DJ. Health-related quality of life and psychological distress in patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection or transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:2107–2111. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He Q, Jiang JJ, Jiang YX, Wang WT, Yang L. Health-related quality of life comparisons after radical therapy for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplant Proc. 2018;50:1470–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shomura M, Kagawa T, Okabe H, Shiraishi K, Hirose S, Arase Y, et al. Longitudinal alterations in health-related quality of life and its impact on the clinical course of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma receiving sorafenib treatment. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:878. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2908-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tian HQ, Li HL, Wang B, Liang GW, Huang XQ, Huang ZQ, et al. Treatment of middle/late stage primary hepatic carcinoma by Chinese medicine comprehensive therapy: a prospective randomized controlled study. Chin J Integr Med. 2010;16:102–108. doi: 10.1007/s11655-010-0102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lv N, Kong Y, Mu L, Pan T, Xie Q, Zhao M. Effect of perioperative parecoxib sodium on postoperative pain control for transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective randomized trial. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:3492–3499. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4207-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chow PK, Machin D, Chen Y, Zhang X, Win KM, Hoang HH, et al. Randomised double-blind trial of megestrol acetate vs placebo in treatment-naive advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:945–952. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuroda H, Ushio A, Miyamoto Y, Sawara K, Oikawa K, Kasai K, et al. Effects of branched-chain amino acid-enriched nutrient for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma following radiofrequency ablation: a one-year prospective trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1550–1555. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chie WC, Blazeby JM, Hsiao CF, Chiu HC, Poon RT, Mikoshiba N, et al. Differences in health-related quality of life between European and Asian patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017;13:e304–e311. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mise Y, Satou S, Ishizawa T, Kaneko J, Aoki T, Hasegawa K, et al. Impact of surgery on quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 2014;38:958–967. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2342-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mikoshiba N, Miyashita M, Sakai T, Tateishi R, Koike K. Depressive symptoms after treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma survivors: prevalence, determinants, and impact on health-related quality of life. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2347–2353. doi: 10.1002/pon.3300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qiao CX, Zhai XF, Ling CQ, Lang QB, Dong HJ, Liu Q, et al. Health-related quality of life evaluated by tumor node metastasis staging system in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2689–2694. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i21.2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meier A, Yopp A, Mok H, Kandunoori P, Tiro J, Singal AG. Role functioning is associated with survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:1669–1675. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0895-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jie B, Qiu Y, Feng ZZ, Zhu SN. Impact of disclosure of diagnosis and patient autonomy on quality of life and illness perceptions in Chinese patients with liver cancer. Psychooncology. 2016;25:927–932. doi: 10.1002/pon.4036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hansen L, Rosenkranz SJ, Vaccaro GM, Chang MF. Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma near the end of life: a longitudinal qualitative study of their illness experiences. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38:E19–E27. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mikoshiba N, Tateishi R, Tanaka M, Sakai T, Blazeby JM, Kokudo N, et al. Validation of the Japanese version of the EORTC hepatocellular carcinoma-specific quality of life questionnaire module (QLQ-HCC18) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:58. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang Z, Wan C, Li W, Cun Y, Meng Q, Ding Y, et al. Development and validation of the Simplified Chinese Version of EORTC QLQ-HCC18 for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Invest. 2015;33:340–346. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2015.1036280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chie WC, Blazeby JM, Hsiao CF, Chiu HC, Poon RT, Mikoshiba N, et al. International cross-cultural field validation of an European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer questionnaire module for patients with primary liver cancer, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality-of-life questionnaire HCC18. Hepatology. 2012;55:1122–1129. doi: 10.1002/hep.24798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Diouf M, Filleron T, Barbare JC, Fin L, Picard C, Bouché O, et al. The added value of quality of life (QoL) for prognosis of overall survival in patients with palliative hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2013;58:509–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li L, Mo FK, Chan SL, Hui EP, Tang NS, Koh J, et al. Prognostic values of EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-HCC18 index-scores in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma-clinical application of health-related quality-of-life data. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:8. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2995-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diouf M, Bonnetain F, Barbare JC, Bouché O, Dahan L, Paoletti X, et al. Optimal cut points for quality of life questionnaire-core 30 (QLQ-C30) scales: utility for clinical trials and updates of prognostic systems in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist. 2015;20:62–71. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hsu WC, Tsai AC, Chan SC, Wang PM, Chung NN. Mini-nutritional assessment predicts functional status and quality of life of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Nutr Cancer. 2012;64:543–549. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2012.675620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shun SC, Chen CH, Sheu JC, Liang JD, Yang JC, Lai YH. Quality of life and its associated factors in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma receiving one course of transarterial chemoembolization treatment: a longitudinal study. Oncologist. 2012;17:732–739. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fan SY, Eiser C, Ho MC, Lin CY. Health-related quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: the mediation effects of illness perceptions and coping. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1353–1360. doi: 10.1002/pon.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Butt Z, Lai JS, Beaumont JL, Kaiser K, Mallick R, Cella D, et al. Psychometric properties of a brief, clinically relevant measure of pain in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2447–2455. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0692-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Phillips R, Gandhi M, Cheung YB, Findlay MP, Win KM, Hai HH, et al. Summary scores captured changes in subjects' QoL as measured by the multiple scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hinrichs JB, Hasdemir DB, Nordlohne M, Schweitzer N, Wacker F, Vogel A, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with initial transarterial chemoembolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2017;40:1559–1566. doi: 10.1007/s00270-017-1681-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hansen L, Dieckmann NF, Kolbeck KJ, Naugler WE, Chang MF. Symptom distress in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma toward the end of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44:665–673. doi: 10.1188/17.ONF.665-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gill J, Baiceanu A, Clark PJ, Langford A, Latiff J, Yang PM, et al. Insights into the hepatocellular carcinoma patient journey: results of the first global quality of life survey. Future Oncol. 2018;14:1701–1710. doi: 10.2217/fon-2017-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kensinger CD, Feurer ID, O'Dell HW, LaNeve DC, Simmons L, Pinson CW, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in liver transplant recipients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Transplant. 2016;30:1036–1045. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qiu B, Li K, Dong X, Liu FQ. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for portal hypertension in hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2017;40:1372–1382. doi: 10.1007/s00270-017-1655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chau I, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Borg C, Malfertheiner P, Seitz JF, Park JO, et al. Ramucirumab as second-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma following first-line therapy with sorafenib: Patient-focused outcome results from the randomised phase III REACH study. Eur J Cancer. 2017;81:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.He Q, Jiang JJ, Jiang YX, Wang WT, Yang L Liver Surgery Group. Health-related quality of life comparisons after radical therapy for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplant Proc. 2018;50:1470–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xing M, Kokabi N, Camacho JC, Kim HS. Prospective longitudinal quality of life and survival outcomes in patients with advanced infiltrative hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein thrombosis treated with Yttrium-90 radioembolization. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:75. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3921-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]