Abstract

Background

Though overdose rates have been increasing in US rural areas for two decades, little is known about the rural risk environment for overdoses. This qualitative study explored the risk environment for overdoses among young adults in Eastern Kentucky, a rural epicenter of the US opioid epidemic.

Methods

Participants were recruited via community-based outreach. Eligibility criteria included living in one of five rural Eastern Kentucky counties; being aged 18–35; and using opioids to get high in the past 30 days. Semi-structured interviews explored the rural risk environment, and strategies to prevent overdose and dying from an overdose. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using constructivist grounded-theory methods.

Results

In this sample (N=19), participants reported using in a range of locations, including homes and outdoor settings; concerns about community stigma and law enforcement shaped the settings where participants used opioids and the strategies they deployed in these settings to prevent an overdose, and to survive an overdose. Almost half of participants reported using opioids in a “trap house” or other dealing locations, often to evade police after buying drugs, and reported that others present pressed them to use more than usual. If an overdose occurred in this setting, however, these same people might refuse to call EMS to protect themselves from arrest. Outdoor settings presented particular vulnerabilities to overdose and dying from an overdose. Most participants reported using opioids outdoors, where they skipped overdose prevention steps to reduce their risk of arrest; they worried that no one would find them if they overdosed, and that cell phone coverage would be too weak to summon EMS.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that initiatives to reduce overdoses in Eastern Kentucky would be strengthened by de-escalating the War on Drugs and engaging law enforcement in initiatives to protect the health of people who use opioids.

Keywords: Risk environment framework, Overdose, Opioids, Stigma, Rural, Appalachia

Introduction

Opioid overdose deaths are a global public health crisis, and have been expanding into rural areas in several countries in recent years (Belzak & Halverson, 2018; Han, 2017; Ho, 2019; King, Fraser, Boikos, Richardson & Harper, 2014; Rintoul, Dobbin, Drummer, Ozanne-Smith, 2011). In the US, residents of non-metro counties now have higher rates of opioid fatalities than residents of metro areas, and opioid poisonings in nonmetropolitan counties have increased at a greater rate than they have in metropolitan counties (Paulozzi & Xi, 2008; Rigg, Monnat & Chavez, 2018). Between 1999 and 2016, small metro, micropolitan (nonmetro), and noncore (nonmetro) counties had the most significant increases in opioid death rates, with increases of 584%, 682%, and 721% respectively (Rigg, Monnat & Chavez, 2018).

Though overdose rates have been increasing in rural areas since the early 2000s, we know very little about the rural risk environment for overdoses. The risk environment framework (“REF”) is a theoretical framework proposed by Rhodes that seeks to explain how contexts influence drug-related harms (Rhodes, 2002). The risk environment itself can be defined as “the space where a variety of factors interact to increase or decrease the chance of harm occurring” (Rhodes, 2009, p.193). Risk environments have three levels of influence: the micro, meso, and macro levels. According to REF, each of these levels has five types of influences: the physical, social, economic, political (Rhodes, 2002), and healthcare/criminal justice intervention environments (Cooper, Bossak, Tempalski, Des Jarlais, & Friedman, 2009; Cooper et al., 2012; Cooper & Tempalski, 2014).

To date, almost all research on risk environments and overdose has been conducted in urban areas. McLean (2016), for example, found that deindustrialization in cities facilitated overdose. Galea et al., (2003) found that the likelihood of death from an overdose was greater than deaths from other causes in urban neighborhoods with more unequal income distribution. Several studies have found that stigma toward people who use drugs (PWUD), a feature of the macrolevel social environment, also creates vulnerability to overdoses among PWUD in cities (Couto e Cruz et al., 2018; Dovey, Fitzgerald & Choi, 2001; Latkin et al., 2019). A recent study by Couto e Cruz et al. (2018), for example, found that experiencing drug-related discrimination, a form of stigma, at least weekly was associated with a 60% higher odds of overdosing (Couto e Cruz et al., 2018).

Research on risk environments and overdoses conducted in cities may not generalize to rural contexts. Past research has identified multiple ways in which rural risk environments may differ from urban environments (Hartley, 2004; Keyes, Cerda, Brady, Havens & Galea, 2014; Palombi, St. Hill, Lipsky, Swanoski, Lutfiyya, 2018; Paulozzi, 2012; Rudolph, Young & Havens, 2017, 2019; Young & Havens, 2012; Young, Havens & Leukefeld, 2010). The healthcare service environment, for example, differs across rural and urban areas: rural areas tend to have fewer substance use disorder treatment services (Ellis, Konrad, Thomas & Morrissey, 2009; Rosenblatt, Andrilla, Catlin & Larson, 2015; Young, Grant & Tyler, 2015), and are experiencing an increasing rate of hospital closures (Kaufman et al., 2016).

The few studies investigating the rural overdose risk environment conducted to date have focused on the physical and social environment (Haven et al., 2011; Rudolph, Young & Havens, 2019). Rudolph and colleagues have found that peers of people who overdosed lived closer to the town center (Rudolph, Young & Havens, 2019). The authors posit that this finding was partially explained by the increased population density and overdose prevalence near the town center. Additionally, Havens and colleagues (2011) found that larger social networks were associated with experiencing more overdoses.

The current investigation builds on this work by exploring the overdose risk environment for young adults living in a rural area. Specifically, in a sample of young adults living in five Appalachian Kentucky counties, we explore (1) the places where young adults go to use opioids to get high; (2) participants’ experiences of the features of the social, economic, physical, political, and healthcare/criminal justice environments of these places; and (3) and the perceived processes through which features of the rural risk environment might influence vulnerability to an overdose occurring and to a fatal overdose. Young adults were the focus of the study, because of the high burden of overdose deaths in this age group: 20% of all deaths among young adults aged 25–34 in the US are opioid-related, as are 12.4% among those aged 15 to 24 (Gomes, Tadrous, Mamdani, Paterson & Juurlink, 2018). The study used REF and Goffman’s theory of stigma (Goffman, 1963) as sensitizing concepts to explore these topics. According to Charmaz (2003, p. 259), “Sensitizing concepts offer ways of seeing, organizing, and understanding experience; they are embedded in our disciplinary emphases and perspectival proclivities”.

II. Methods

Setting

This study was conducted in five rural Appalachian counties in Eastern Kentucky. To avoid compounding stigma, we are not publishing their names. These five counties have high rates of drug overdoses; from 2015 to 2017, the age-adjusted opioid death rate was 22.8 deaths per 100,000 residents, almost two times the national rate of 12.8 deaths per 100,000 residents (CDC Wonder, 2018). Between 23% and 32% of residents in these counties live in poverty, created in part by the downsizing of coal mining (Hendryx, 2009; Scott, McSpirit, Breheny & Howell, 2012), workforce de-unionization, and outmigration (Tighe, 2013; Ulrich-Schad, Henly, & Safford, 2013). The opioid epidemic has heavily impacted eastern Kentucky. Beginning in the 1990s, prescription opioid analgesics flooded into Eastern Kentucky’s socioeconomically distressed communities (Leukefeld et al., 2005; Leukefeld, Walker, Havens, Leedham & Tolbert, 2007; Moody, Satterwhite, & Bickel, 2017), facilitated by targeted prescription pain-pill marketing, and loose regulations (Dyer, 2014; Luu et al., 2018). These communities were already strained by a high prevalence of chronic pain from work-related injuries and unmet mental health needs (Hendryx, 2009; Moody et al., 2017). As a result, this region experienced increasing injection initiation and fatal overdoses (Bunn & Slavova, 2012), particularly among young adults (Young & Havens, 2012). Subsequently, policies aimed at curbing the supply of opioid analgesics expanded demands for heroin as a cheaper alternative (Victor, Walker, Cole & Logan, 2017).

Recruitment

The current investigation utilized purposive sampling, seeking variation in gender and age. Young adults who used opioids to get high were recruited between March and August of 2017 using multiple outreach strategies, including cookouts, flyers, and peer recruitment. Cookouts aided in recruitment by providing a low-threshold, inviting environment that allowed potential participants to approach study staff informally, to build relationships, and learn about the study on their own terms. Interested individuals contacted study staff to learn more about the study. Participants were eligible if they resided in one of the five Eastern Kentucky counties; were aged 18 to 35; reported using prescription opioid pain relievers and/or heroin to get high in the past 30 days; and were able to read English. Eligible individuals underwent a consent process, and consenting individuals took part in one-on-one semi-structured interviews with one of the authors (HC, DC, or AY) or trained study staff. Each interview took place in the community, in a place that allowed privacy and safety (e.g., cars near cookouts, and offices within local community-based organizations).

Data Collection

The interview guide was informed by REF and harm reduction principles and explored the different types and levels of influence in the rural risk environment as well as harm reduction topics like risk behaviors for overdose and strategies to prevent an overdose from occurring, and strategies to survive an overdose once it had occurred. Interviews were audio-recorded and lasted 60–90 minutes; participants received $30 for taking part in the interview. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim. Participants completed a brief survey before the qualitative interview that queried sociodemographic characteristics and drug use behaviors.

Grounded theory analysis

Constructivist grounded theory methods were used to analyze the transcripts (Charmaz, 2003; Glaser & Strauss, 2017; Strauss & Corbin, 1998); these methods recognize that individuals enter the field and analyze data with sets of pre-existing assumptions and theories. Our analysis was guided by the REF, Goffman’s stigma theory, and harm reduction principles; these models and principles informed analysis as sensitizing concepts, defined above. Coding applied in vivo and in vitro codes, with in vitro codes reflecting harm reduction behaviors and REF domains. As the analysis progressed and it became clear that stigma was important, we added codes drawn from Goffman’s stigma theory (e.g. “stigma”, “internalized stigma”) to understand and give context to the findings. We used reflexivity (e.g., memos) to scrutinize these models and principles (Strauss & Corbin, 1998; Charmaz, 2017).

The codebook was developed by several co-authors. The codebook was based on REF, stigma theory, harm reduction principles, prior literature, and a system of open coding. The codes were organized by REF domains (e.g. social environment, physical environment, etc.) and included constructs from Goffman’s conceptualization of stigma (Goffman, 1963). Transcripts were open coded by the researcher (MF), and the coding of every 5th transcript was reviewed for consistency by one of the principal investigators (HC). Any discrepancies were discussed, negotiated and reconciled. Following Grounded Theory methods, we applied axial coding and selective coding to identify and describe emergent properties and categories, analyze intersections of categories, and explore perceived pathways through which REF constructs might affect vulnerability to overdose and to an overdose becoming fatal. Some of the categories that arose included, “social environment: community stigma towards people who use opioids (PWUO)”, and “health service environment: poor Naloxone Access”. Transcripts were coded and organized using NVivo 12 (QSR International, Cambridge, MA).

Ethics

Emory University’s Institutional Review Board approved all data collection protocols for this study. Participants underwent a consent process prior to each interview. Audio files and transcripts were stored on a HIPAA-compliant server; paper documents were stored in alocked cabinet accessible only to project staff. Data were protected by a federal Certificate of Confidentiality.

III. Results

Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of eleven men and eight women who ranged in age from eighteen to thirty-four, with an average age of 26.3 (standard deviation [sd]=4.2; Table 1). Consistent with the sociodemographic composition of the area, where the majority of the population in Appalachian Kentucky is White, Non-Hispanic (Pollard, 2004), all participants identified as White, Non-Hispanic. The average length of time a participant lived in their home county was 10.7 years (sd=10.3). Participants reported using multiple drugs to get high within the past 30 days: 90% (n=17) of participants reported recently using prescription opioids, and 47% (n=9) reported recently using heroin. Most participants (74%, n=14) reported injecting at least one type of drug in the past 30 days; heroin, prescription opioids, and methamphetamines were the most commonly injected drugs.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of a sample of young adults (N=19) who use opioids to get high in rural Eastern Kentucky

| Characteristics | Mean / N | SD / % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 26.3 | 4.2 |

| Lived in County (years) | 10.7 | 10.3 |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 11 | 57.90% |

| Women | 8 | 42.10% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 19 | 100% |

| Experiences with overdose (lifetime) | 10 | 52.6% |

| Self-reported overdose | 3 | 15.7% |

| Witnessed an overdose | 3 | 15.7% |

| Overdose of close friend/family member | 6 | 31.6% |

| Overdose of aquaintance | 3 | 15.7% |

| Opioid use settings (from qualitative interviews) | ||

| Homes | 18 | 94.7% |

| Public Bathroom | 16 | 84.2% |

| Outdoors | 16 | 84.2% |

| Vehicles | 13 | 68.4% |

| Drug dealing locales | 8 | 42.10% |

| Drugs used (past 30 days; multiple responses permitted; most commonly reported answers presented here) | ||

| Heroin | 9 | 47.4% |

| Prescription opioids | 17 | 89.5% |

| Methamphetamines | 11 | 57.9% |

| Injected drugs (past 30 days) | 14 | 76.1% |

| Drugs injected (past 30 days; multiple responses permitted; most commonly reported answers presented here) | ||

| Heroin | 8 | 42.1% |

| Prescription opioids | 9 | 47.4% |

| Methamphetamines | 7 | 36.8% |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Some elementary or middle school | 1 | 5.30% |

| Some High School | 6 | 31.60% |

| High School | 8 | 42.10% |

| Some College | 4 | 21.10% |

Qualitative Findings

Overview of grounded theory

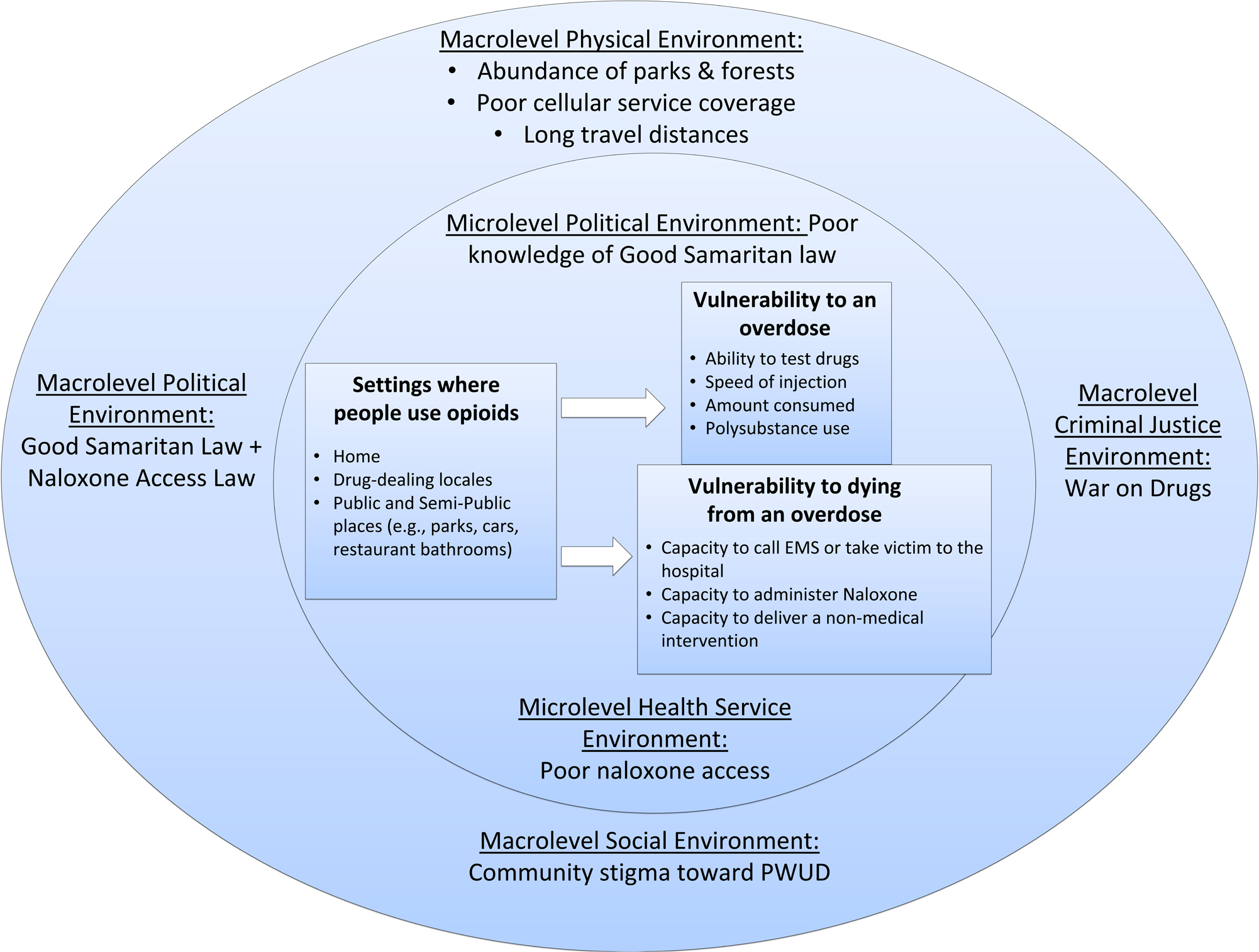

Figure 1 illustrates the main categories that arose from our analysis. At the macro level, the physical environment was characterized by parks and forests, poor cellular phone service and long travel distances; Good Samaritan Law and Naloxone access law passed in 2015 comprised the political environment; the War-on-Drugs encompassed the criminal justice environment; and finally the social environment consisted of high levels of community stigma toward PWUD. At the micro level, the health service environment included poor Naloxone access; the political environment encompassed poor knowledge of the Good Samaritan law; the physical environment included settings where people use opioids and features that influence vulnerability to an overdose occurring (ability to test drugs, etc.) along with vulnerability to dying from an overdose (capacity to administer Naloxone, etc.). As assumed in the REF, one level can influence subsequent levels and interact in ways that compound and ameliorate risk (Rhodes 2002; Rhodes 2009).

Fig 1.

Diagram of grounded theory

In the following sections, we describe participants’ experiences with overdose; the perceived roles of stigma and other features of the rural risk environment in determining the settings where they used opioids to get high; and participants’ experiences of the ways in which characteristics of these settings, and the broader rural risk environment, shaped whether they and others could deploy strategies to protect themselves from experiencing (1) an overdose, and (2) a fatal overdose (see Figure 1). Strategies and salient features of the rural risk environment varied according to whether the individual was trying to avoid an overdose or trying to survive an overdose, and so we present findings in two sections, one on overdose occurrence and the other on overdose survival.

Experiences of Overdose

Ten of the nineteen participants had personally overdosed, witnessed an overdose, or knew someone who had overdosed; some participants fell into several categories, experiencing at least two of the aforementioned overdose scenarios. Although not every participant had a personal or close experience with overdose, participants live in an area with high rates of overdose and are deeply aware and impacted by the phenomena. Three participants had personally survived an overdose (two had survived several); three had witnessed an overdose; six had partners, close friends, or family who overdosed; and three reported acquaintances that had overdosed. Overall, participants reported that overdoses were an inevitable and devastating consequence of opioid use. One participant explained that overdosing was inescapable for most particularly if one was seeking a strong high:

…Most people chase after that kind of high to where they are nodding out. And when you start nodding out you [are] overdosing

(Katie1, 27-year-old woman; Overdose experience: multiple close friends [non-fatal and fatal], family member [non-fatal]).

Ten participants discussed the dangers of laced heroin or other drugs. Illicit fentanyl was present in the heroin supply, and participants reported that it contributed to a higher incidence of overdose in the area

[Fentanyl] is going around. It’s been in the newspaper and I don’t understand why people don’t read that and slow down…it seems like they would see that and lower their dose. Instead it seems like they’re injecting more

(Leslie, 34-year-old woman; Overdose experience: none).

Overdose onset could be extremely rapid, as one participant explained: “Every time [my brother] overdoses, it’s 20 seconds after he [uses opioids].” While none of the witnessed overdoses resulted in death, five participants had lost family members or friends to overdose:

That’s how [my uncle] died: mixing Xanax and heroin…and just fell asleep and never woke up. He was just on the couch at a party, and everybody was partying around him. They didn’t know until the next day…

(Alex, 18-year-old man; Overdose experiences: multiple personal [non-fatal], multiple family members [fatal and non-fatal]).

While some participants expressed sadness at losing friends and family members to an overdose, many participants used angry and judgmental language to describe these events and blamed the individual for overdosing. As one participant explained,

I have had a lot of friends pass away the past couple months. It was just because of pure stupidity, because they want to get higher than what they was the other day

(Katie, 27-year-old woman; Overdose experience: multiple close friends [non-fatal and fatal], family member [non-fatal]).

Rural Risk Environment: Stigma

Drug-related stigma was a potent and pervasive feature of the rural risk environment where these overdoses occurred. Once perceived as an “addict” individuals were ostracized and viewed negatively by other community members:

Once somebody is labeled as an addict… nobody will talk to you. You are automatically just a piece of crap. You are not a person anymore. You’re just somebody that doesn’t need to be here

(John, 24-year-old man).

He explained that this was especially relevant for people who inject drugs because injecting carried a higher stigma than other methods of drug delivery like smoking or ingesting:

…In high school, I would crush Xanax up in my textbook and snort them in my classroom. When it comes to snorting a drug or marijuana smoking, [you can do it] anywhere… [Injecting is] different. People judge you more if they see you shooting up… you constantly feel like a piece of shit, but you don’t want other people to see tha ttoo… People that shoot up won’t do it around people that don’t

(John, 24-year-old man).

Some participants felt that local stigma was so extreme that community members did not care when people died of an overdose, “…’if they OD, they deserve to die.’ That’s a lot of peoples’ attitude towards it”.

The War on Drugs can be understood as a codification of stigma, and the police were a highly salient feature of the criminal justice environment. Fear of police was especially relevant for PWUO who had records because they were known by law enforcement and more likely to be singled out: “A lot of drug addicts, they have warrants or whatever. They are scared.” However, avoiding police interaction could be difficult in this rural context because:

Up here … it’s a lot different than the cities. You were talking about big cities and everything. [People in cities] get away with a lot more stuff; but in towns like this, cops don’t have [as much to do]…Cops up here will pull you over for something small, just because they’re small little counties [with fewer people]…

(Adam, 19-year-old man).

The consequences for police interaction were severe, even in emergency situations, as one participant explained,

My brother OD’d at a gas station… luckily the guy with him was a good friend. He called 911, and actually got caught with heroin and is doing two years in prison for it. For calling 911, because my brother was dying

(Alex, 18-year-old man).

As we discuss below, stigma and other features of the rural risk environment shaped the settings where participants and others used opioids to get high and the extent to which they could deploy strategies to prevent an overdose from occurring and from an overdose becoming fatal, in these settings.

Stigma and drug-use settings

Potent and pervasive stigma – including the risk of arrest – toward PWUO shaped the settings where participants and others used opioids to get high. Participants reported opioid use occurring in three settings: homes, drug-dealing sites, and public and semi-public spaces (i.e., public bathrooms, vehicles, and outdoor settings). Here, we describe these settings, and participants’ discussions of why they and others might use in them.

Homes

In a community with high levels of stigma toward PWUD, participants’ homes, or friends’ and family members’ homes, provided a safe, private, relaxing setting that they could control. Almost all (94.7%) of the sample reported homes as an opioid use setting for local young adults (Table 1). Homeowners could dictate who was allowed to enter the premises, decreasing fears of detection by non-users, law enforcement, and others.

If I do something I try to do it at home [so] I can just relax. [At home] I don’t have to worry about being out in public and talking to the cops…I don’t have to look over my shoulder. I sit at home and I am comfortable. Nobody can bother me

(Sarah, 27-year-old woman).

Given concerns about arrest, privacy was especially crucial for PWUO who had a record or were on probation or parole:

We always do stuff like that at home. [I’m] afraid to take anything out[side] and get caught with it....Cause I just done 5 years in prison over drugs

(Alan, 27-year-old man).

Drug dealing locales

When they could not use at home, participants often used drugs where they bought them, at trap houses and dealers’ homes. Forty-two percent of the sample reported trap houses or dealer’s homes as a setting where local young adults used opioids (Table 1). Using in the same location where they bought drugs allowed PWUO to minimize their risk of arrest, and rapidly treat withdrawal symptoms. Trap houses were likened to “shooting galleries” and “crack houses,” and were typically a house or trailer where individuals could buy and openly use drugs, and socialize without fear of stigma:

[Trap houses are] the most laid back place…You already know everybody, and the trap house is cool… and you usually already know who you’re dealing with…there ain’t nobody in there, like, in a trap house, that ain’t cool

(Adam, 19-year-old man).

Trap Houses were also described as full of activity and people. When a participant was asked what happens in trap houses, she replied,

…What’s not happening there? There’s people in an out all of the time. And nobody really respects privacy in a trap house. Knocking on doors is a thing of that past, if there is a door

(Sarah, 27-year-old woman).

Dealers’ homes, in contrast, were more intimate settings, where the social flow was more controlled. Not all dealers allowed their customers to use drugs on the premises or to stay and “hang out” and some customers preferred not to use where they bought drugs unless they were experiencing dope sickness. Whether a dealer allowed customers and others to use in their home depended on how well they knew each other.

Public and semi-public spaces

Because of stigma, law enforcement activity, withdrawal, and privacy needs, using at home was not always possible. Some participants lived with family members or others who were unaware of their opioid use, and PWUO felt that it was inappropriate to use around them. As a result, PWUO might use elsewhere:

If the person cannot do it at their home, if they can’t find a friend’s home to use, they’ll stop at a gas station and just go in the bathroom where they can lock the door

(25-year-old man, Mark).

When they could not use at home, or at a place of purchase, participants reported using opioids in public and semi-public settings, including public bathrooms, parks, and vehicles. Eighty-four percent of the participants reported single- and multi-stall public bathrooms as a setting where local young adults used opioids (Table 1). Located in restaurants, stores, and gas stations, these bathrooms were often close to where people bought drugs and thus helped minimize the possibility of arrest for drug possession; this proximity also reduced suffering from withdrawal which was likened to “feeling like you’re dying”, making it difficult for participants to make it home before using their opioids.

In addition, several counties where participants lived were home to municipal, state, and national parks and 84% of participants reported outside settings like parks, wooded areas, and recreational spaces as salient opioid use settings for local young adults (Table 1). Participants had no privacy or control over passersby when using in parks, and feared detection by non-PWUO. Detection by police in these settings was also a common concern. As one participant explained,

…You’re taking a high risk [using in a park]; and everybody’s afraid of incarceration, because that’s a big charge

(Mark, 25-year-old man).

Participants also reported that local PWUO who could not use at home might use in their vehicle; 68% of participants reported that local young adults used opioids in vehicles (Table 1). Cars and trucks provided a modicum of privacy in an outdoor setting, where others could not see what they were doing. As one participant explained:

[After buying drugs,] I’d probably drive from that stop sign to that power pole… and just pull off…alone enough that the people I bought it off of [didn’t see] and just do it…I don’t do nothing in front of my family…Too much respect for them

(Alan, 27-year-old man).

Settings: overdose prevention strategies

These settings shaped whether or not participants could engage in specific strategies to prevent an overdose from occurring. First, we describe the strategies that participants used to prevent an overdose, and then we describe how these settings shaped whether they could deploy them.

Eight participants used smaller amounts of opioids to avoid overdosing, and twelve tried to avoid mixing drugs:

[People can protect themselves from overdose by] not mixing the pills, like Xanax, klonopin, pain killers… [or] if they do mix them, they watch how much they take

(Michelle, 33-year-old woman).

Twelve participants said that PWUO test their drugs before using it to determine its potency and purity. They did so by snorting or tasting it, and if the substance tingled, tasted or “felt” right then they consumed it; some dealers allowed participants to test substances before purchasing them.

Preventing an overdose at home

According to participants, PWUO were able to engage in these overdose prevention strategies most easily when they were at home, either their home or that of a friend or family member. Homes provided a high level of protection from law enforcement and offered privacy from interference of non-PWUO. For example, one participant said, “I feel safer at home.”

Another participant explained that, in this circumstance,

…I won’t do it anywhere besides home or friends’ house…where I know it would be safe… and [I could] take [my] time and concentrate…

(Richard, 26-year-old man).

Barriers to preventing an overdose in dealing locales

These settings had two common features that undermined participants’ overdose prevention strategies and made preventing an overdose difficult. First, participants reported that dealers and others present encouraged and enabled them to consume more drugs:

…[These places are] where the peer pressure is put on. Once they take that first shot and get feeling good, the dealer might say “hey do you want some more?”

(John, 24-year-old man).

Second, many types of drugs were available in these settings, facilitating polysubstance use:

Someone that I get drugs off of [might say], “Here try this out, you can have it” [or] you know, “just see what it is”

(Aaron, 26-year-old man).

Preventing an overdose in public and semi-public settings

When using in public and semi-public spaces (i.e., bathrooms, outdoors, vehicles), PWUO felt rushed, and were unable to test the strength of their drugs routinely,

If [PWUO] go to public places they have to rush [and can’t test their drugs] if they don’t want no one seeing them

(Becky, 25-year-old woman).

Police patrolled some parks – particularly municipal parks – heavily:

“Cops…literally circle the park every 45 minutes to an hour. And do a full sweep”

(Danielle, 26-year-old woman).

Thus, participants did not want to have anything incriminating on their person, so they were motivated to use all their drugs, consuming more than usual to get rid of evidence and losing control over the dosage and speed of drug consumption. As one participant reported, when PWUO use in a park,

…you are in a rush…because you know you just want to do it all. You don’t want to carry the stuff around with you…and that…might cause an overdose

(Alex, 18-year-old man).

Cars and other vehicles were viewed as semi-private spaces that provided some protection from detection when using outdoors, but less protection than a home. PWUO could use more safely in vehicles because they felt more concealed and therefore, less fearful of detection or rushed compared to a public space. In a car, one participant explained,

…you’re concealed really, and you can do it anywhere…well concealed is like, you know, hypothetically, if you wanted…to shoot, put a needle right now, not many people’s going to see it…because they can’t see in the car

(Mark, 25-year-old man).

Many participants sought out public bathrooms because they were accessible and had a locking door; these locking doors provided more privacy from non-PWUO and law enforcement officers than other public settings. Single-stall bathrooms were more desirable than multi-stall bathrooms because they provided more protection from non-PWUO and law enforcement, and thus allowed PWUO to engage in overdose protection strategies such as testing drugs and injecting slowly.

Preventing an Overdose: Negative Cases

The analysis identified some negative cases – that is, concepts and people that did not align with our emerging grounded theory. In contrast to participants who felt that using in public and semi-public spaces exacerbated overdose risks, two participants reported that fear of detection could be protective if the individual used a smaller amount of the drug in their haste:

“Bathrooms…probably somebody else right behind you…they would be in a hurry…They wouldn’t get to do as much as they probably normally would if they had more time”

(Luke, 34-year-old man).

Finally, although a greater sense of security at home was protective against rushed injections, a decreased sense of risk might contribute to consuming larger “doses” of drugs, placing PWUO at an increased risk of overdose. One participant explained how this atmosphere lead to increased consumption:

At home…I’m going to sit here and get fucked up today. I’m at home, I ain’t going nowhere. I’ve heard it too many times. They just sit there and keep snorting and shooting…all through the day. And the next things you know you come back a couple hours later and there he is… dead or OD

(Alan, 27-year-old man).

Settings: Strategies to survive an overdose

Participants also discussed several strategies to promote survival, should they overdose; the extent to which they could deploy these strategies varied across settings. Notably, naloxone was not easily accessible to PWUO in these communities. Participants reported that PWUO in the community did not carry Naloxone, and many participants reported that local PWUO did not know what Naloxone was or where to acquire it. Only one participant possessed naloxone, and another participant knew someone who possessed it; both had Naloxone because of previous overdose experiences.

In the absence of naloxone, PWUO reported that the primary strategy they deployed to survive an overdose was to use with other people who might call emergency medical services (EMS), or implement less effective home remedies to help overdose victims survive (e.g., slapping the individual, putting them in a cold bath). Using alone was considered dangerous:

If you’re trying [a new drug] or getting it from somewhere new… you never want to do it alone…You do it alone, nobody is there to bring you back…

(Tom, 29-year-old man).

However, using with others was only protective if the individual(s) present were willing to revive the victim or call EMS. Most participants were unaware of Kentucky’s Good Samaritan law, passed in 2015 that protected people who reported an overdose to EMS from prosecution for drug possession. When asked if Kentucky had a Good Samaritan law, for example, one participant replied, “I don’t know if there is or not. I’m not sure.” Several expressed great interest in having Good Samaritan legal protections:

…if they just make it to where its not your fault that person OD’ed …[then] they can get help instead of having to worry about going to prison for life

(Becky, 25-year-old woman).

Additionally, participants frequently reported that bystanders, especially homeowners, were at risk of arrest or being charged with murder if they were with someone who died of an overdose:

…You can get charged with murder. [For example] me and my buddy are out. He can’t get no dope. I got him some dope. We go to this house, and he shoots his dope, and he dies. Now I am going to get charged with murder, because I got him that dope. They can charge me with … reckless manslaughter… or some crazy stuff.

(Tom, 29-year-old man).

As we discuss below, some participants were willing to endure significant legal consequences in order to help overdose victims, though this capacity varied by setting and by the strength of their relationship to the victim, as we describe below.

Surviving an overdose at home

While the majority of participants discussed home as the most ideal setting to use opioids and to prevent an overdose from occurring because of the privacy and control these settings allowed, this privacy could be deadly if an overdose occurred. Participants’ felt protected by their home’s locking doors: behind these locked doors, they could use drugs without fear of discovery and shame, and free from law enforcement surveillance. If an overdose occurred, however, these locks became a dangerous barrier that prevented others from offering help, increasing the chances that an overdose would become fatal. One participant explained,

…You lock that door and nobody can get into to you…they ain’t going to know if you overdosed or not…

(Michelle, 33-year-old woman).

One way to survive an overdose at home was to keep doors unlocked. As one participant also expressed,

I always tell people…just don’t lock the door behind you… my brother…he would try to hide it from me. But, I try to make it okay with him…Just so he would tell me, so I could know that if my brother is down in the bathroom right now or not

(Alex, 18-year-old man).

Thus many participants tried to use at home with others, in the hopes that these witnesses would revive them if they overdosed. One participant explained that at home,

…I always had family around me that didn’t do drugs, that were watching me [in case an overdose occurred]

(Erica, 25-year-old woman).

Not all witnesses to an overdose in the home, however, could be counted on to call EMS. Many participants explained that fear was the first reaction to a witnessed overdose, fear for the person’s life and also fear of legal consequences for the witness(es). Witnesses were fearful that calling EMS might result in arrest if drugs were present in the home. Fear of arrest shaped witness responses to overdose in homes, by discouraging witnesses from calling EMS, or from staying with the victim until EMS arrived.

The people that’s getting high with a friend at their house, or at their friend’s house…when they start overdosing…the friend gets scared and they will not call an ambulance. They will not call the police. They just leave them there…

(Katie, 27-year-old woman).

Witnesses who were on community supervision were even less likely to call, for fear that they would be arrested for violating probation or parole. Moreover, police could question witnesses about the source of the opioids and could arrest and charge individuals present if they had supplied the opioids causing the overdose. As one participant reported,

Some people won’t [call 911] cause they are afraid they will get into trouble because the drug’s come from them…

(Richard, 26-year-old man).

While homeowners could help reduce the risk of an overdose by deciding who could and could not be present, homeowners could also exercise this control to refuse to allow anyone present to call EMS:

…some people would try and hold you back from calling 911 [They] would literally beat the crap out of you…, especially if it is not your home and it’s theirs because you know people can get in trouble for [overdosing]…

(Becky, 25-year-old woman).

We note, however, that the strength of a witness’s relationship with the victim could overcome the fear of arrest and homeowner threats. One participant reported that at home if “a really good friend that is just there…[they] will save your life…” regardless of the consequences. When participants in this sample reported personally calling EMS or witnesses calling EMS, a partner, close friend, or family member had overdosed, and their ties to the victim overcame fears of potential consequences.

Surviving an overdose in dealing locales

Many features of trap houses and dealers’ homes, such as the presence of drugs and open drug use, increased PWUOs’ vulnerability to dying from an overdose once an overdose occurred. As in homes, overdosing in a trap house was dangerous because witnesses might refuse to summon EMS or might delay calling EMS until it was too late, in order to avoid arrest for drug or paraphernalia possession at the scene. As one participant explained,

I would be afraid to call, because I would be like, “Oh my God, I’m going to go to jail again”

(Susan, 25-year-old woman).

Some participants, however, reported that there would be many people present at a trap house, and perhaps at least one of them might mobilize to offer assistance: “if the people [in] there actually care…you will be less likely to die because there will be people there.” Witnesses at a trap house would have to balance the desire to prevent death against the need to protect inhabitants from arrest. For example, instead of calling EMS to the trap house, participants reported that trap house witnesses might drive the victim to the hospital or call someone else to take them.

If you’re in a trap house or a place where you just did drugs or something, no one’s going to want this dude OD-ing in their house…They’re going to be, like, ‘we need to get this dude out of here’…They’d drop him off at a hospital and they wouldn’t go inside with him

(Adam, 19-year-old man).

Surviving an overdose in public and semi-public settings

Vulnerability to dying from an overdose in a public bathroom partly depended on whether the bathroom had a single-stall or multi-stall structure. Similar to locked doors in homes, locked doors in single-stall public bathrooms were successful at shielding PWUO from detection while using but could be a dangerous impediment to surviving an overdose. Others outside the locked door might not realize that the inhabitant was overdosing, delaying medical attention and increasing the likelihood of death. For example, one participant explained,

“If you’re using a local bathroom, the door’s locked, and it’s one bathroom… no one’s really probably going to be able to help you. That would be a big risk there”

(Mark, 25-year-old man)

Multi-stall bathrooms, in contrast, offered more chance for survival. In multi-stall bathrooms, a non-PWUO could intervene if an overdose were to occur because they would be more likely to notice the person in distress, and less likely to worry about the legal consequences of calling EMS. One participant reasoned, “…Somebody could find’em at least …”

As noted, some PWUO used outdoors, partly because the remoteness of parks and other outdoor recreational areas provided more privacy than other non-residential settings. This remoteness, however, also made it difficult to survive an overdose, especially if using alone. In the event of an overdose, medical attention would be delayed because of how infrequently or sporadically others came through the area. One participant explained,

…You can overdose [alone] up on [name of park], there’s so many different spots… that you can go. It could take people…days to weeks to realize you haven’t come home or even to think to go there and look

(Danielle, 26-year-old woman).

As noted for other settings, when PWUO used with others in these remote settings, they could not rely on these witnesses to intervene. As one participant reported, they would not want to “rat themselves out over [someone] OD-ing.” Witnesses who did try to summon EMS, however, had to contend with barriers to responding that were less salient in other settings. Cellular phone service was often poor in particularly remote areas. Additionally, EMS might have trouble finding and reaching some of these remote settings, potentially delaying critical medical attention. One participant explained,

…there are some spots up [here]– it’s just hard [for help] to get to, because it’s more country and not so close to town

(Luke, 34-year-old man).

Negative cases

A few participants reported that they would intercede in an overdose and call EMS regardless of the situation or their relationship to the victim. These participants viewed it as a moral obligation and were less fearful of potential consequences because:

…I wouldn’t care. I would call. They can charge me … I could not live with knowing that I didn’t pick up the phone. I am a junkie but I am not a bad person…”

(Sarah, 27-year-old woman).

They reported that saving a life was more important than being stigmatized by law enforcement, EMS, and society.

Discussion

Our analysis suggests that in these rural Eastern Kentucky counties stigma, a feature of the macrolevel social environment, and the war on drugs, a codification of stigma manifesting in the macrolevel criminal justice environment, shaped the settings where young adults used opioids. Because of the tightly interconnected social environment, stigma was heightened; while the large population sizes of cities provides anonymity, in these rural areas information about individuals circulates quickly and widely to those with whom PWUO interact. Thus, once labeled “an addict” individuals faced significant discrimination, exclusion and shame that could affect their social status, employment prospects, criminal justice encounters and access to health care. Arrest and interaction with law enforcement was of great concern; with a low ratio of population to police, once law enforcement identified an individual as a PWUO, they could be stopped or harassed more frequently, increasing stigma, marginalization and fear. In turn, the social and physical features of these settings appeared to influence whether these young adults could deploy strategies to protect themselves from an overdose and survive an overdose. Similar to studies with PWUD in cities (Harris, Richardson, Frasso & Anderson, 2018; Rhodes et. al., 2007; Small, Rhodes, Wood & Kerr, 2007), we found that these rural young adult PWUO preferred to use at home, partly because that setting’s protection from stigma and law enforcement allowed them to use strategies to prevent an overdose. When the fear of arrest, non-PWUO presence, and withdrawal made it difficult to use at home, PWUO used in trap houses and other dealing locales and public and semi-public settings.

While PWUD in urban areas commonly report using in some of these settings (e.g., public bathrooms, dealers’ homes [Sutter, Curtis & Frost, 2019; Small et. al., 2007; Latkin et. al, 2019]), remote recreational areas, and vehicles may be more common in rural areas and present unique risk environments. These differences arise from decreased population density, lack of cellular phone service, and a reliance on vehicles as a mode of transportation in rural areas. Eighty-four percent of the sample reported that local young adults used outdoors, some in remote areas where no one would be present to offer help if they overdosed, and where poor cellular phone service or long travel distances might thwart aid if others sought it. Coupled with a lower density of hospitals and other medical services, this physical and social risk environment engenders higher levels of overdose risk than what is typically found in urban areas. In a sparsely populated area, there are few passersby to help someone suffering an overdose; even if EMS were called they may have difficulty locating the individual or may not be able to reach them, depending on the terrain.

Though the War on Drugs of the 1980s and 1990s was waged against urban communities of color as a mechanism to maintain racial/ethnic and class hierarchies in post-Jim Crow era (Weiss Riley et al., 2018), it has since travelled with the burgeoning opioid epidemic into predominately White, non-Hispanic rural areas, transforming these risk environments. National data reveal that rural counties are experiencing greater increases in arrest rates than their more urbanized counterparts; a study in these same five counties by Cooper et al. (2019) found that 39.7% of PWUO or PWID had a history of arrest. In this qualitative sample, young adult PWUO – residents of rural counties where >95% of residents were non-Hispanic White – reported significant police activity and fear of arrest and incarceration. Arrest and incarceration spurred on by the War on Drugs does little to impact illicit drug use and many times increases drug related violence (Abadie et al., 2018). As has been found in countless studies in cities (Burris et. al., 2004; Cooper, Moore, Gruskin & Krieger, 2005; Dovey et. al., 2001; Small, Kerr, Charette, Schechter & Spittal, 2006;) this fear shaped the settings where PWUD used drugs and the strategies they could use to protect their health. In light of these findings and escalating arrest rates in rural areas, we recommend that public health agencies, PWUD, and their allies in rural areas mobilize against policies that prioritize turning to punitive measures (courts, corrections) to solve issues related to drug use, and partner with law enforcement to reduce the harms of policing for the PWUD’s health.

Beletsky’s SHIELD intervention and LEAD are two possible avenues for action (Arredondo et al., 2019). SHIELD is a theoretically guided training for officers designed to “harmonize police practices with overdose crisis response, including lay responder naloxone access, Good Samaritan laws, syringe services, opioid substitution therapy, and other public health measures” (Health in Justice Action Lab, n.d, p.1) LEAD provides pre-arrest diversion to PWUD, diverting them from jail to case management and supportive services (Collins, Lonczak & Clifasefi, 2017). Notably, the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition has implemented rural LEAD programs in North Carolina (North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition [NCHRC], n.d). In addition to public health benefits, anti-War-on-Drug arguments could highlight spiraling incarceration costs that are overwhelming rural counties’ budgets (Ruddell & Mays, 2007).

A large body of literature has described ways that the war on drugs has disrupted urban macrolevel and microlevel social environments: partners of incarcerated individuals experience economic and emotional devastation; children suffer – often across their lifetimes – when they lose a parent to incarceration; and community networks and political capital are disrupted when residents cycle through the criminal justice system (Clear, Rose & Ryder, 2001; Cooper et al., 2014, 2015; Wildeman & Wang, 2017). As found in cities (Koester et. al., 2017; Latimore & Bergstein, 2017; Pollini et. al., 2006;), the war on drugs jeopardized ties among these rural young adult PWUO in crisis: they faced a devastating choice between calling EMS to save an overdose victim and saving themselves from arrest. Social relationships are a well-established source of strength and resilience in rural areas, including in rural Kentucky (Keyes et al., 2014). In contrast to urban areas, individuals report greater familiarity and closer relations among members in their social network (Keyes et al., 2014; Beggs, Haines & Hurlbert, 1996). The War on Drugs threatens these vital relationships by pitting self-interest against compassion during an overdose.

Notably, two years before we conducted these interviews Kentucky’s macrolevel political environment altered considerably: the state passed a Good Samaritan law, and expanded Naloxone access. Two years after this law passed, however, our data indicate few of these rural young adult PWUO were aware of these changes: few knew of the Good Samaritan law’s existence, and almost none had Naloxone. Ensuring that community members have Naloxone and know about the Good Samaritan law’s protections could save lives by leveraging these rural PWUO’s protective microlevel social relationships rather than eroding them.

Limitations and Strengths

We used Maxwell’s framework to consider the study’s validity (Maxwell, 1992). Descriptive validity (i.e., the extent to which we captured what was said) was strengthened by using verbatim transcripts and comparing the transcripts to audio recordings. Interpretive validity (i.e., the extent to which the researcher captured participants’ meanings) was enhanced through extensive reflective and descriptive memo-ing. Though transcripts were coded by one coder (MF), HC reviewed the coding of every fifth transcript and provided feedback on codes, code applications, and discrepancies. Theoretical validity was enhanced by a search for negative cases.

The majority of participants were from the most densely populated of the five counties; two individuals represented two other counties. We tried to recruit participants from all five counties for a representative sample; however, we had trouble reaching PWUO in the least populous areas, highlighting a weakness of our study. We suspect that their experiences with the risk environment and overdose are different from PWUO living in more populous counties.

Conclusions

Though the opioid epidemic and overdoses have caused significant suffering in rural areas in the US and elsewhere for decades, few studies have sought to describe the local risk environment for overdoses in rural areas. We find that stigma and its codification in the War on Drugs, including fear of arrest, criminalization, and incarceration, shape the settings where young adult PWUO use opioids, and their capacity to prevent overdoses and overdose deaths in these settings. Our analysis identified several opportunities to promote the health of young adult PWUO in these five rural counties. Opportunities include de-escalating the War on Drugs and engaging law enforcement in efforts to support the health of PWUD, and more comprehensively implementing 2015 Good Samaritan and Naloxone Access laws by disseminating Naloxone to PWUO and other community members and educating PWUO of their right to call EMS to save friends, family members, and others from an overdose without fear of legal consequences.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21 DA042727; PIs: Cooper and Young; UG3 DA044798; PIs: Young and Cooper). We are grateful to our participants, for courageously sharing their personal experiences and knowledge with study staff.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Pseudonyms were used to protect the identity of participants

REFERENCES

- Abadie R, Gelpi-Acosta C, Davila C, Rivera A, Welch-Lazoritz M, & Dombrowski K (2018). “It ruined my life”: The effects of the War on Drugs on people who inject drugs (PWID) in rural Puerto Rico. International Journal of Drug Policy, 51, 121–127. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo J, Beletsky L, Baker P, Abramovitz D, Artamonova I, Clairgue E, Morales M, Mittal ML, Rocha-Jimenez T, Kerr T, Banuelos A, Strathdee SA, and Cepeda J (2019). Interactive Versus Video-Based Training of Police to Communicate Syringe Legality to People Who Inject Drugs: The SHIELD Study, Mexico, 2015–2016. American Journal of Public Health, 109, 921–926, Doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beggs J, Haines V & Hurlbert J (1996). Revisiting the rural-- urban contrast: personal networks in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan settings. Rural Sociol, 61 (2):306–325. Doi: 10.1111/j.1549-0831.1996.tb00622.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belzak L, & Halverson J (2018). The opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. Health promotion and chronic disease prevention in Canada: research, policy and practice, 38(6), 224–233. Doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.38.6.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn T, Slavova S (2012). Drug overdose morbidity and mortality in Kentucky, 2000–2010: An examination of statewide data, including the rising impact of prescription drug overdose on fatality rates, and the parallel rise in associated medical costs. Kentucky Injury Prevention and Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.mc.uky.edu/kiprc/PDF/Drug_Overdose_Morbidity_and_Mortality_in_Kentucky_2000_-_2010-final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Burris S, Blankenship KM, Donoghoe M, Sherman S, Vernick JS, Case P, Lazzarini Z, Koester S (2004). Addressing the “risk environment” for injection drug users: the mysterious case of the missing cop. The Milbank quarterly, 82(1), 125–156. Doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00304.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [Dataset] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (2018). Multiple Cause of Death 1999–2017 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released December, 2018 Accessed from http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html

- Charmaz K (2003). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods In Denzin NK, & Lincoln YS (Eds.), Strategies for qualitative inquiry (2nd ed., pp. 249–291). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2017). The Power of Constructivist Grounded Theory for Critical Inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(1), 34–45. Doi: 10.1177/1077800416657105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clear TR, Rose DR, & Ryder JA (2001). Incarceration and the Community: The Problem of Removing and Returning Offenders. Crime & Delinquency, 47(3), 335–351. Doi: 10.1177/0011128701047003003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, Lonczak HS,Clifasefi SL (2017). Seattle’s Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD): Program effects on recidivism outcomes. Evaluation and Program Planning. (64):49–56, Doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Bossak B, Tempalski B, Des Jarlais D, & Friedman S (2009). Geographic approaches to quantifying the risk environment: Drug-related law enforcement and access to syringe exchange programmes. International Journal of Drug Policy, 20(3), 217–226. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Clark C, Barham T, Embry V, Caruso B, & Comfort M (2014). “He Was the Story of My Drug Use Life”: A Longitudinal Qualitative Study of the Impact of Partner Incarceration on Substance Misuse Patterns Among African American Women. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(1–2), 176–188. Doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.824474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Des Jarlais D, Tempalski B, Bossak B, Ross Z, & Friedman S (2012). Drug-related arrest rates and spatial access to syringe exchange programs in New York City health districts: Combined effects on the risk of injection-related infections among injectors. Health & Place, 18(2), 218–228. Doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Moore L, Gruskin S, & Krieger N (2005). The impact of a police drug crackdown on drug injectors’ ability to practice harm reduction: A qualitative study. Social Science & Medicine, 61 (3), 673 – 684. Doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HL, Caruso B, Barham T, Embry V, Dauria E, Clark CD, & Comfort ML (2015). Partner Incarceration and African-American Women’s Sexual Relationships and Risk: A Longitudinal Qualitative Study. Journal of urban health: bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 92(3), 527–547. Doi: 10.1007/s11524-015-9941-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HL, & Tempalski B (2014). Integrating place into research on drug use, drug users’ health, and drug policy. The International journal on drug policy, 25(3), 503–507. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HLF, Crawford ND, Haardörfer R, Prood N, Jones-Harrell C, Ibragimov U, Ballard AM, Young AM (2019). Using Web-Based Pin-Drop Maps to Capture Activity Spaces Among Young Adults Who Use Drugs in Rural Areas: Cross-Sectional Survey. JMIR Public Health Surveil;5(4):e13593 DOI: 10.2196/13593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto e Cruz C, Salom CL, Dietze P, Lenton S, Burns L, Alati R (2018). Frequent experience of discrimination among people who inject drugs: Links with health and wellbeing. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 190, 188–194. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovey K, Fitzgerald J, & Choi Y (2001). Safety becomes danger: Dilemmas of drug use in public space. Health and Place, 7, 319–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer O (2014). Kentucky seeks $1 bn from Purdue Pharma for misrepresenting addictive potential of oxycodone. British Medical Journal, 349 :g6605 Doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Thomas KC, Morrissey JP (2009). County-level estimates of mental health professional supply in the United States. Psychiatr Serv., 60, 1315–1322. Doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.10.1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Vlahov D, Coffin P, Fuller C, Leon A, & Tardiff K (2003). Income distribution and risk of fatal drug overdose in New York City neighborhoods. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 70(2), 139–148. Doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00342-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG & Strauss AL (2017). Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Routledge, New York: Doi: 10.4324/9780203793206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E (1963). Stigma; notes on the management of spoiled identity (Print ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice - Hall [Google Scholar]

- Gomes T, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN (2018). The Burden of Opioid-Related Mortality in the United States. JAMA Netw Open,1(2):e180217 Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han E (2017) Prescriptions opioids are killing more Australians than heroin: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 17th July 2019 from https://www.smh.com.au/healthcare/prescription-opioids-are-killing-moreaustralians-than-heroin-australian-bureau-of-statistics-20170720-gxf5wa.html

- Harris RE, Richardson J, Frasso R, Anderson ED (2018). Perceptions about supervised injection facilities among people who inject drugs in Philadelphia, International Journal of Drug Policy, 52, 56–61. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley D (2004). Rural health disparities, population health, and rural culture. American journal of public health, 94(10), 1675–1678. Doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JR, Oser CB, Knudsen HK, Lofwall M, Stoops WW, Walsh SL, Leukefeld CG, Kral AH (2011). Individual and network factors associated with non-fatal overdose among rural Appalachian drug users. Drug and alcohol dependence, 115(1–2), 107–112. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health in Justice Action Lab. (n.d). The shield model concept note. Retrieved from https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/1367d9_692720eecd42455d8d530a3b7729a4d9.pdf

- Hendryx M (2009). Mortality from heart, respiratory, and kidney disease in coal mining areas of Appalachia. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 82 (2) pp. 243–249. Doi: 10.1007/s00420-008-0328-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho J (2019). The Contemporary American Drug Overdose Epidemic in International Perspective. Population and Development Review. 45(1), 7–40. Doi: 10.1111/padr.12228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman B, Thomas S, Randolph R, Perry J, Thompson K, Holmes G, & Pink G (2016). The Rising Rate of Rural Hospital Closures. The Journal of Rural Health, 32(1), 35–43. Doi: 10.1111/jrh.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Brady JE, Havens JR, & Galea S (2014). Understanding the rural-urban differences in nonmedical prescription opioid use and abuse in the United States. American journal of public health, 104(2), e52–e59. Doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N, Fraser V, Boikos C, Richardson R & Harper S (2014). Determinants of Increased Opioid-Related Mortality in the United States and Canada, 1990–2013: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health. 104, e32 – e42. Doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester S, Mueller S, Raville L, Langegger S, & Binswanger I. (2017). Why are some people who have received overdose education and naloxone reticent to call Emergency Medical Services in the event of overdose? International Journal of Drug Policy, 48, 115 – 124. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimore A, & Bergstein R (2017). Caught with a body” yet protected by law? Calling 911 for opioid overdose in the context of the Good Samaritan Law. International Journal of Drug Policy, 50, 82 – 89. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin C, Gicquelais R, Clyde C, Dayton L, Davey-Rothwell M, German D, Falade-Nwulia S, Saleem H, Fingerhood M, Tobin K (2019). Stigma and drug use settings as correlates of self-reported, non-fatal overdose among people who use drugs in Baltimore, Maryland. International Journal of Drug Policy, 68, 86–92. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leukefeld C, McDonald HS, Mateyoke-Scrivner A, Roberto H, Walker R Webster M, Garrity T (2005). Prescription drug use, health services utilization, and health problems in rural Appalachian Kentucky. Journal of Drug Issues, 35 (3): 631–643. Doi: 10.1177/002204260503500312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leukefeld C, Walker R Havens J, Leedham CA, Tolbert V (2007). What does the community say: Key informant perceptions of rural prescription drug use. Journal of Drug Issues, 37 (3): 503–524. Doi: 10.1177/002204260703700302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luu H, Slavova S, Freeman PR, Lofwall M, Browning S, Bush H (2018). Trends and Patterns of Opioid Analgesic Prescribing: Regional and Rural-Urban Variations in Kentucky From 2012 to 2015. The Journal of Rural Health, 35: 97–107. Doi: 10.1111/jrh.12300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JA (1992). Understanding and validity in qualitative research. Harvard Educational Review, 62(3), 279–300. Doi: 10.17763/haer.62.3.832332085625182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLean K (2016). “There’s nothing here”: Deindustrialization as risk environment for overdose. International Journal of Drug Policy, 29, 19 – 26. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody L, Satterwhite E, & Bickel WK (2017). Substance Use in Rural Central Appalachia: Current Status and Treatment Considerations. Rural mental health, 41(2), 123–135. Doi: 10.1037/rmh0000064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition. (n.d). Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion. Retrieved from http://www.nchrc.org/lead/law-enforcement-assisted-diversion/

- Palombi L, Hill C St., Lipsky M, Swanoski M, & Lutfiyya M (2018). A scoping review of opioid misuse in the rural United States. Annals of Epidemiology, 28(9), 641–652. Doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulozzi LJ (2012). Prescription drug overdoses: a review. J Safety Res., 43, 283 – 289. Doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulozzi LJ & Xi Y (2008). Recent changes in drug poisoning mortality in the United States by urban–rural status and by drug type. Pharmacoepidem. Drug Safe, 17: 997–1005. Doi: 10.1002/pds.1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard KM (2004). A “new diversity”: Race and ethnicity in the Appalachian region. Washington, DC: Appalachian Regional Commission; http://www.arc.gov/assets/research_reports/anewdiversityraceandethnicityinappalachia.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Pollini RA, McCall L, Mehta SH, Celentano DD, Vlahov D & Strathdee SA (2006). Response to overdose among injection drug users. Am J Prev Med, 31, 261–264. Doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T (2002). The ‘risk environment’: a framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. International Journal of Drug Policy, 13(2), 85 – 94. Doi: 10.1016/S0955-3959(02)00007-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T (2009). Risk environments and drug harms: A social science for harm reduction approach. International Journal of Drug Policy, 20(3), 193 – 201. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Watts L, Davies S, Martin A, Smith J, Clark D (2007). Risk, shame and the public injector: A qualitative study of drug injecting in South Wales. Social Science & Medicine, 65(3), 572–585. Doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigg KK, Monnat S, Chavez MN (2018). Opioid-related mortality in rural America: Geographic heterogeneity and intervention strategies. International Journal of Drug Policy, 57, 119 – 129. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rintoul AC, Dobbin MDH, Drummer OH, Ozanne-Smith J (2011). Increasing deaths involving oxycodone, Victoria, Australia, 2000–09. Injury Prevention,17, 254–259. Doi: 10.1136/ip.2010.029611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH, Catlin M, & Larson EH (2015). Geographic and specialty distribution of US physicians trained to treat opioid use disorder. Annals of family medicine, 13(1), 23–26. Doi: 10.1370/afm.1735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddell R, & Mays G (2007). Rural jails: Problematic inmates, overcrowded cells, and cash-strapped counties. Journal of Criminal Justice, 35 (3) pp: 251–260. Doi: 10.1016/J.JCRIMJUS.2007.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph A, Young A, & Havens J (2017). Examining the Social Context of Injection Drug Use: Social Proximity to Persons Who Inject Drugs Versus Geographic Proximity to Persons Who Inject Drugs. American Journal of Epidemiology, 186(8), 970–978. Doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph A, Young A, & Havens J (2019). Using Network and Spatial Data to Better Target Overdose Prevention Strategies in Rural Appalachia. Journal of Urban Health, 96(1), 27–37. Doi: 10.1007/s11524-018-00328-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SL, McSpirit S, Breheny P, & Howell BM (2012). The Long-Term Effects of a Coal Waste Disaster on Social Trust in Appalachian Kentucky. Organization & Environment, 25(4), 402–418. Doi: 10.1177/1086026612467983 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Kerr T, Charette J, Schechter MT, Spittal PM (2006) Impacts of intensified police activity on injection drug users: Evidence from an ethnographic investigation. International Journal of Drug Policy,17, 2 Doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Rhodes T, Wood E, & Kerr T (2007). Public injection settings in Vancouver: Physical environment, social context and risk. International Journal of Drug Policy, 18(1), 27–36. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, & Corbin JM (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory: Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sutter A, Curtis M, & Frost T (2019). Public drug use in eight U.S. cities: Health risks and other factors associated with place of drug use. International Journal of Drug Policy, 64, 62–69. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tighe JR (2013). Responding to the Foreclosure Crisis in Appalachia: A Policy Review and Survey of Housing Counselors. Housing Policy Debate, 23:1, 111–143, Doi: 10.1080/10511482.2012.751931 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich-Schad JD, Henly M and Safford TG (2013). Migration Intentions. Rural Sociol, 78: 371–398. Doi: 10.1111/ruso.12016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Victor GA, Walker R, Cole J, Logan TK (2017). Opioid analgesics and heroin: Examining drug misuse trends among a sample of drug treatment clients in kentucky. The International Journal of Drug Policy, 46: 1–6. Doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss Riley R, Kang-Brown J, Mulligan C, Valsalam V, Chakraborty S, & Henrichson C (2018). Exploring the Urban–Rural Incarceration Divide: Drivers of Local Jail Incarceration Rates in the United States. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 36(1), 76–88. Doi: 10.1080/15228835.2017.1417955 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman C, & Wang EA (2017). Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA. The Lancet, 389(10077), 1464–1474. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30259-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, & Havens JR (2012). Transition from first illicit drug use to first injection drug use among rural Appalachian drug users: a cross-sectional comparison and retrospective survival analysis. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 107(3), 587–596. Doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Havens JR, & Leukefeld CG (2010). Route of administration for illicit prescription opioids: a comparison of rural and urban drug users. Harm reduction journal, 7, 24 Doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-7-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LB, Grant KM & Tyler KA (2015) Community-Level Barriers to Recovery for Substance-Dependent Rural Residents. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 15:3, 307–326, DOI: 10.1080/1533256X.2015.1056058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]