Abstract

Although tobacco (TOB) and marijuana (MJ) are often co-used in pregnancy, little is known regarding the joint impact of MJ+TOB on offspring development, including the developing neuroendocrine stress system. Further, despite evidence for sex-specific impacts of prenatal exposures in preclinical models, the sex-specific impact of prenatal MJ+TOB exposure on offspring neuroendocrine regulation in humans is also unknown. In the current study, overall and sex-specific influences of MJ+TOB co-use on offspring cortisol regulation were investigated over the first postnatal month. 111 mother-infant pairs from a low-income, racially and ethnically diverse sample participated. Based on Timeline Followback data with biochemical verification, three groups were identified: (1) prenatal MJ+TOB, (2) TOB only, and (3) controls. Baseline cortisol and cortisol stress response were assessed at seven points over the first postnatal month using a handling paradigm in which saliva cortisol was assessed before, during, and following a standard neurobehavioral assessment (NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale). A significant exposure group by offspring sex interaction emerged for baseline cortisol over the first postnatal month (p=.043); MJ+TOB-exposed males showed 35–36% attenuation of baseline cortisol levels vs. unexposed and TOB-exposed males (ps≤.003), while no effects of exposure emerged for females. Both MJ+TOB and TOB-exposed infants showed a 22% attenuation of cortisol stress response over the first postnatal month vs. unexposed infants (ps<.03), with evidence for sex-specific effects in exploratory analyses. Although results are preliminary, this is the first human study to investigate the impact of prenatal MJ exposure on infant cortisol and the first to reveal a sex-specific impact of prenatal MJ+TOB on cortisol regulation in humans. Future, larger-scale studies are needed to elucidate mechanisms and consequences of sex-specific effects of MJ and MJ+TOB on the developing neuroendocrine stress system.

Keywords: pregnancy, marijuana, tobacco, infant, sex differences, cortisol

1. Introduction

Tobacco (TOB) and marijuana (MJ) are some of the most prevalent prenatal substance exposures in the U.S. and worldwide. Although rates of cigarette smoking in pregnancy have decreased in recent decades (Tong et al., 2013); approximately one in ten women continue to smoke during pregnancy in the U.S. (Curtin and Matthews, 2016; Drake et al., 2018; Martin et al., 2018). In addition, use of other tobacco products such as electronic cigarettes and hookah in pregnancy is growing (Kapaya et al., 2019; Kurti et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019). Rates of MJ use in pregnancy have increased dramatically over the last decade (Tong et al., 2013; Young-Wolff et al., 2019), paralleling expanding societal acceptance, medicalization, legalization and decriminalization of marijuana in the U.S. (Pew Research Center, 2015). In addition, the potency of Δ9-tetrahydro-cannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive chemical in MJ, has increased 300% since 1995 (Chandra et al., 2019; ElSohly et al., 2016; Mehmedic et al., 2010). Current estimates of prenatal MJ prevalence are approximately one in twenty women (Brown et al., 2017; Ko et al., 2015; Volkow et al., 2017). Both prenatal TOB and MJ are more common in poor, young, and less-educated women (Ko et al., 2015; Kondracki, 2019; Martin et al., 2018).

Approximately one-fourth of pregnant TOB users report MJ co-use; rates of TOB co-use in pregnant MJ users are even higher, with two-thirds to three fourths of pregnant MJ users reporting TOB co-use (Chabarria et al., 2016; Coleman-Cowger et al., 2017; El Marroun et al., 2008; Ko et al., 2015). Relative to TOB-only users, pregnant MJ+TOB co-users are also more likely to be young mothers of Black race or Hispanic ethnicity (Coleman-Cowger et al., 2017). In the general population, MJ+TOB co-use has been associated with poorer MJ and TOB cessation outcomes, increased psychiatric conditions including MJ and TOB use disorders, and altered respiratory function (Agrawal et al., 2012; Peters et al., 2012; Peters et al., 2014; Rabin and George, 2015). However, despite high rates of prenatal TOB+MJ co-use, only a small number of studies have investigated maternal and offspring health risks related to MJ+TOB co-use in pregnancy. These studies have revealed increased maternal and neonatal morbidity--including increased rates of pre-eclampsia and preterm birth and decreased birthweight and head circumference—as well as increased rates of maternal prenatal psychiatric and substance use disorders in co-users vs. sole or non-users (Chabarria et al., 2016; Coleman-Cowger et al., 2018; Coleman-Cowger et al., 2017; Emery et al., 2016; Gray et al., 2010).

An emerging literature has also highlighted links between prenatal MJ+TOB exposure and altered offspring neurobehavior across development. One recent study revealed evidence for associations between prenatal MJ+TOB co-exposure and increased MJ+TOB co-use in adult offspring, highlighting the possibility that prenatal MJ+TOB co-exposure may be one mechanism underlying the intergenerational transmission of use of MJ and TOB (De Genna et al., 2018). In addition, several studies have revealed both direct and indirect associations between prenatal MJ+TOB exposure and behavioral regulation in infancy and early childhood (Eiden et al., 2018; Godleski et al., 2018; Schuetze et al., 2018; Schuetze et al., 2019). For example, in a study of 18-month old infants, prenatal MJ-exposed offspring—the majority of whom were also exposed to TOB--showed increased attention deficits and aggressive behavior (El Marroun et al., 2011). In another study, prenatal MJ+TOB co-exposure was associated with altered autonomic regulation at nine months, which led to decreased emotion regulation at twenty-four months (Eiden et al., 2018). Finally, our group revealed associations between prenatal MJ+TOB and alterations in offspring self-soothing and need for external soothing across the first postnatal month (Stroud et al., 2018b). However, although there is emerging evidence for associations between prenatal MJ+TOB and offspring neurobehavior, mechanisms underlying these associations are not known.

1.1. Prenatal programming of the offspring HPA axis

Supported by epidemiologic links between low birthweight and an array of health outcomes, the “developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD)” hypothesis highlights the profound importance of the prenatal environment in “programming” fetal adaptations (e.g., alterations in physiological systems and growth) that predispose offspring to cardiovascular and behavioral health and disease in later life (Eriksson, 2016; O’Donnell and Meaney, 2017; Van den Bergh et al., 2017). It is postulated that low birthweight, per se, is not at the heart of these disorders, but rather that common factors influence the intrauterine environment and fetal growth and “program” physiological systems leading to lasting changes in developmental trajectories, and ultimately, to disease. Physiological changes are believed to help the fetus/infant adapt in the short-term to a stressful pre/postnatal environment, but may predispose offspring to physical disease and mental disorders over the long-run. In particular, dysregulation of offspring hypothalamic pituitary adrenocortical (HPA) axis has been proposed as one of several inter-related common pathways underlying prenatal “programming” of adult health and disease (Hamada and Matthews, 2019; O’Donnell and Meaney, 2017; Van den Bergh et al., 2017).

We propose alterations in offspring HPA regulation as one potential mechanism underlying the impact of prenatal MJ on alterations in offspring neurodevelopment. Specifically, maternal prenatal MJ exposure may program the fetal HPA axis leading to long-term neuroendocrine and neurobehavioral alterations. Supporting this hypothesis, a number of converging lines of research highlight associations between MJ use, the endocannabinoid system, and the HPA axis. In non-pregnant adults, both chronic and acute MJ use have been associated with altered basal and stress reactive cortisol regulation (Cservenka et al., 2018). In addition, a growing body of animal and human research has highlighted reciprocal interactions between glucocorticoid and endocannabinoid signaling system (Micale and Drago, 2018). For example, cannabinoid receptors are highly expressed in brain regions associated with glucocorticoid signaling, glucocorticoids can mobilize the endocannabinoid system, and cannabinoid receptors play a role in negative feedback inhibition of the HPA system (Micale and Drago, 2018). Finally, a small number of preclinical studies have revealed alterations in offspring basal HPA regulation and HPA stress response in rats exposed to THC or other cannabinoid compounds (del Arco et al., 1999; Rubio et al., 1998; Rubio et al., 1995).

There is also evidence that maternal prenatal TOB exposure may program the fetal HPA axis. Similar to prenatal MJ, there are reciprocal interactions between the stress, HPA, and nicotinic systems (Balkan and Pogun, 2018; Kassel et al., 2003). Further, prenatal TOB exposure has been associated with increased cord blood cortisol levels (McDonald et al., 2006; Varvarigou et al., 2009; Varvarigou et al., 2006). In animal models, prenatal nicotine exposure has also been associated with altered HPA response to stress and nicotine exposure in adult offspring (He et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2012; Poland et al., 1994a; Poland et al., 1994b; Xu et al., 2012). Finally, several human studies have revealed effects of prenatal TOB on alterations in neonatal and infant cortisol regulation. Specifically, prenatal TOB has been associated altered basal and stress responsive cortisol in offspring at four days, and two, seven, and nine months of age (Eiden et al., 2015; Haslinger et al., 2018; Ramsay et al., 1996; Schuetze et al., 2008). Our group also found 23% attenuation of baseline cortisol and 28% attenuation of cortisol stress response in TOB-exposed versus unexposed infants over the first postnatal month (Stroud et al., 2014a).

To our knowledge, however, no human studies have investigated the impact of prenatal MJ or prenatal MJ+TOB exposure on offspring HPA regulation. In the present study, we conducted a preliminary test of this hypothesis through investigating the impact of prenatal MJ+TOB versus TOB exposure on HPA dysregulation in infant offspring.

1.2. Sex-specific effects in prenatal programming and prenatal exposure models

Sex differences have been documented at multiple levels of fetal programming pathways, including the maternal preconception and prenatal neuroendocrine milieu, placental structure, function and epigenetic regulation, and a variety of offspring outcomes across development (Bale, 2011; DiPietro et al., 2011; Gifford and Reynolds, 2017; Sandman et al., 2013; Sundrani et al., 2017). Sexual dimorphism has also been demonstrated in fetal programming of offspring HPA regulation, such that female offspring show greater vulnerability to programming effects on HPA stress reactivity, while males show greater vulnerability to programming effects on basal HPA regulation (Carpenter et al., 2017). Sandman et al. (2013) proposed that while males show more extreme morbidity and mortality (viability) following exposure to adverse prenatal environments, females demonstrate a more flexible response to prenatal adversity leading to improved viability, but increased vulnerability to subtle alterations that may predispose them to female-specific disorders later in life (e.g., affective disorders).

Several studies have also revealed sex differences in effects of both prenatal TOB and prenatal MJ on offspring neurobehavior (Jacobsen et al., 2007). Specifically, associations between prenatal TOB exposure and offspring tobacco and substance use disorders were evident in female but not male offspring, while associations between prenatal TOB and offspring disruptive behavior disorders emerged in male but not female offspring (Brennan et al., 2002; Coles et al., 2012; Fergusson et al., 1998; Kandel et al., 1994; Stroud et al., 2014b; Weissman et al., 1999). Prenatal MJ exposure was associated with increased infant inattention and aggression in female but not male offspring (El Marroun et al., 2011). Our group and others also demonstrated sex differences in the impact of prenatal MJ+TOB co-use on infants and toddlers. Specifically, prenatal MJ+TOB exposure was associated with greater alterations in newborn self-soothing and toddler behavior problems in female versus male offspring (Godleski et al., 2018; Stroud et al., 2018b).

Finally, and most relevant to the proposed study, prior animal and human studies have revealed sex-specific effects of prenatal THC and TOB exposure on offspring HPA regulation. In rodents prenatally exposed to THC, males showed attenuated basal corticosterone levels and increased corticosterone reactivity to morphine-induced place preference task, while females showed increased basal corticosterone and attenuated reactivity (del Arco et al., 1999; Rubio et al., 1998; Rubio et al., 1995). In addition, in two human studies that investigated sex-specific effects of prenatal TOB exposure, effects on offspring cortisol stress reactivity were most pronounced for male offspring (Eiden et al., 2015; Schuetze et al., 2008).

Given evidence for sex differences in prenatal programming pathways, sex-specific effects of prenatal MJ+TOB exposure on offspring behavior, and sexual dimorphism in offspring HPA regulation following exposure to prenatal THC and TOB, the present study also explored sex-specific influences of MJ+TOB versus TOB exposure on infant cortisol regulation.

1.3. The Present Study

Although several converging lines of research have highlighted reciprocal interactions between MJ, TOB and the HPA axis, to our knowledge, no studies have investigated the impact of MJ+TOB co-use on offspring cortisol regulation in humans. Thus, our first goal was to investigate the impact of prenatal MJ+TOB vs. TOB-only versus no substance exposure on newborn baseline cortisol and cortisol reactivity to handling stress over the first postnatal month. We hypothesized that MJ+TOB-exposed newborns would show altered baseline and reactive cortisol versus unexposed infants; we also explored the hypothesis that co-exposed infants would show altered cortisol regulation versus TOB-exposed infants. Given evidence for sex-specific prenatal programming effects and preliminary sex-specific effects of MJ+TOB, our second goal was to explore the sex-specific impact of prenatal MJ+TOB vs. TOB only vs. no substance exposure on newborn cortisol regulation.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Overview.

Participants for the present study were drawn from the Behavior and Mood in Babies and Mothers (BAM BAM) study, an intensive, short-term, prospective study of maternal use of tobacco (TOB) over pregnancy and infant stress response and behavior over the first postnatal month (Stroud et al., 2018a; Stroud et al., 2014a; Stroud et al., 2016). Pregnant women were recruited from obstetrical offices, health centers, and community postings and enrolled during late second or third trimester of pregnancy. Mothers completed up to four interview sessions between 26 and 42 weeks gestation depending on the timing of study enrollment and their availability. Meconium was collected following delivery for biochemical verification of prenatal nicotine, THC, and other substance exposure. Newborn stress response sessions were conducted up to 7 times over the first postnatal month; each session included four saliva samples measured before and following infant handling (NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale) that were assayed for cortisol.

2.2. Participants

Participant eligibility was determined by maternal-report and medical record review. Maternal exclusion criteria included: age <18 or >40 years, regular illicit drug use besides MJ, involvement with child protective services, and serious medical conditions. Infants were healthy singletons born >36 weeks gestational age (GA) without any identified congenital anomalies or serious medical conditions. All procedures were reviewed and approved by local Institutional Review Boards. Of the 148 pregnant women originally enrolled in BAM BAM, six were excluded for regular opiate or cocaine use, two for involvement with child protective services, five for serious maternal medical conditions, and six for delivery ≤ 36 weeks gestation. Ten infants who were missing cortisol data were also excluded from analyses. Finally, four participants who were missing self-report data regarding MJ use and four who reported MJ only, but not TOB use were excluded from analyses given our focus on MJ+TOB co-use. The final sample (N=111) included three groups: (1) MJ+TOB users (MJ+TOB, n=24), (2) TOB-only users (TOB, n=45), and (3) controls (n=42). Assignment to each of the groups (MJ+TOB, TOB, or Control) was based on data from both maternal report and biomarkers (meconium for MJ and saliva cotinine for TOB). Specifically, the MJ+TOB group included participants whose maternal report and/or biomarkers were positive for TOB (25% maternal report only, 0% biomarker only, and 75% maternal report + biomarker) and whose maternal report and/or biomarkers were positive for MJ (79% maternal report only, 13% biomarker only; 8% maternal report + biomarker). The TOB group included participants whose maternal report and/or biomarkers were positive for TOB (29% maternal report only, 0% biomarker only, and 71% maternal report + biomarker), and whose maternal report and biomarkers were negative for MJ. The Control group included participants whose maternal report and biomarkers were negative for both MJ and TOB. Infants included 51 females and 60 males.

2.3. Study Procedures

2.3.1. Maternal interview sessions

Pregnant women completed between two to four (M=3, SD=1) interview sessions during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy and at delivery at M =31 (SD=2), 35 (SD = 1), and 36 (SD = 1) weeks gestation and 1 (SD=1) days post-delivery. During each interview session, participants completed an adapted Timeline Followback (TLFB) interview--a structured, calendar/anchor-based assessment covering daily TOB, MJ, and other substance use over pregnancy and three months prior to conception (Robinson et al., 2014). Participants also provided information regarding demographic characteristics, caffeine consumption, environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure, health and pregnancy history and depression. Saliva samples for cotinine determination were collected at each session. Finally, maternal weight was measured during third trimester.

2.3.2. Newborn Stress Response Testing

Cortisol stress response was elicited across the first postnatal month using the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS) administered by certified examiners. The NNNS is a comprehensive neurobehavioral assessment that includes observation, neurological and behavioral components as well as exposure to auditory, visual, social, and non-social stimuli (Lester et al., 2004; Tronick and Lester, 2013). The NNNS lasts approximately 30 minutes (M=27; SD=5.4) and involves mild stress as the infant is undressed, observed and handled during periods of sleep, awake, crying, and non-crying states. Four saliva samples were collected for cortisol during and following the NNNS (baseline, end of NNNS, 20 and 40 minutes post-NNNS) using the sorbette sampling device (www.Salimetrics.com). Every effort was made to wake infants from sleep or soothe infants to a calm state prior to the first saliva sample. Saliva samples were also assayed for cotinine to determine infant exposure to nicotine via ETS/breast milk. Stress response testing occurred seven times (Med=7, M=6) over the first postnatal month at days 0 (M=8 hours), 1, 2, 4, 5, 11, and 32 (SDs=0.1, 0.3, 0.3, 0.6, 0.4, 2.3, and 3.1 days). One hundred percent of stress response testing on days 0 and 1 was conducted in the hospital, 56% of stress response testing on days 2—4 was conducted in the hospital, and 99% of stress response testing on days 5—32 was conducted at participants’ homes. Although most studies suggest that the cortisol diurnal rhythm is not yet mature until after the first postnatal month (Custodio et al., 2007; Joseph et al., 2015), NNNS exams were typically scheduled in the morning (Ms = 8:45–11:38 am on days 1–32). Time between last feeding and the start of the NNNS was recorded for use as an a priori covariate in multivariate models.

2.4. Biomarkers and Bioassays

2.4.1. Maternal and infant saliva cotinine

Saliva cotinine is a reliable biomarker for nicotine levels (Jarvis et al., 1987). Maternal and infant saliva samples were frozen until analysis by Salimetrics using expanded range highly-sensitive enzyme immunoassay (HS-EIA; www.Salimetrics.com). Intra and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 6.4% and 6.6% respectively.

2.4.2. Infant saliva cortisol

Saliva cortisol provides a reliable, non-invasive estimate of free (unbound) cortisol (Gunnar et al., 1985) used to determine infant HPA regulation. Cortisol was assayed by Salimetrics using expanded range HS-EIA. Intra and inter-assay coefficients of variation for cortisol samples were 4.6% and 6%.

2.4.3. Meconium nicotine and cannabinoid biomarkers

Meconium analysis reflects cumulative fetal exposure to substances during third trimester (Gray et al., 2009b; Ostrea, 1999). Diapers were collected for 3 days after birth; meconium samples from diapers were combined until the appearance of milk stool. Samples were frozen until analysis then analyzed for nicotine markers (nicotine, cotinine, trans-3′-hydroxycotinine), cannabinoid markers (Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC (THCCOOH), cannabinol, 11 hydroxy THC, di-OH-THC) opiates, cocaine, and amphetamines via enzyme multiplied immunoassay technique (EMIT) screens, and tandem liquid chromatography mass spectrometry or gas chromatography mass spectroscopy confirmation (Gray et al., 2009b; Moore et al., 1998). All samples were negative for cocaine, opiates, and amphetamines. Samples with nicotine markers ≥10 ng/g were considered positive for TOB; samples with cannabinoid markers ≥10 ng/g were considered positive for MJ (Gray et al., 2009a).

2.5. Potential Confounders

Potential confounders of the association between prenatal TOB and MJ+TOB and infant outcomes included: Maternal demographics: age, race/ethnicity (% Non-Hispanic White), Hollingshead SES (low SES ≥ 4); and pregnancy history: gravida, parity, and gestational age at first prenatal visit were assessed by maternal report. Maternal gestational medical conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) were determined by maternal report and medical chart review at delivery. Weight gain over pregnancy was assessed by maternal report (pre-pregnancy) and study measurement (35±1 weeks). Maternal depressive symptoms were assessed by structured interview using the 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton, 1960). Maternal alcohol use was assessed through TLFB interview (Robinson et al., 2014). Maternal caffeine use and environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure were assessed by structured interview; infant ETS exposure was assessed by infant saliva cotinine levels. Infant characteristics: sex, delivery mode, GA at birth, small for GA (SGA; birth weight < 10th percentile for GA), Apgar were assessed by medical chart review. Feeding method (breast vs. bottle) was assessed by maternal report.

2.6. Statistical analysis

A trapezoidal formula was applied to the four saliva cortisol measures taken at each infant stress response session to produce an integrated cortisol response measure (area under the curve; AUC (Pruessner et al., 2003)). Baseline cortisol and cortisol AUC were symmetrized via logarithmic transformation due to significant skewness. Associations between substance exposure groups (MJ+TOB, TOB, Control) and evolution of infant cortisol response (baseline, AUC) over the first postnatal month were investigated using Generalized Least Squares (GLS) regression modeling (Fitzmaurice et al., 2011) as implemented in the nlme library of R 3.4.2 (https://cran.r-project.org).

GLS regression modeling is an extension of repeated measures analysis of covariance, that allows for: (a) heteroscedastic variances, (b) correlations between baseline and AUC cortisol over time, (c) time-varying covariates (e.g., time since feeding for each neurobehavioral exam), and (d) intermittent missingness over time. Infant age was log-transformed; thus, an exponentiated regression coefficient estimated the relative change in the outcome of interest from birth to each follow up visit. Exposure group by infant age interactions were also tested. Regression models controlled for time since feeding (in minutes, log-transformed) to sharpen inferences for associations between substance-exposure group and infant stress response. AUC analyses were also adjusted for differences in baseline cortisol.

Overall differences between the exposure groups in both initial outcome levels at the first stress response testing (intercept) and with respect to infant age at stress response testing over the first postnatal month (linear slope) were tested using multivariate Wald tests with 2 degrees of freedom. Omnibus tests were followed by examination of pairwise contrasts: MJ+TOB vs. Control, TOB vs. Control, and MJ+TOB vs. TOB. Both omnibus and pairwise tests were adjusted for significant confounders.

Each potential confounder was tested individually in relation to exposure group (MJ+TOB, TOB, Control) and then in relation to outcomes of interest (baseline and AUC cortisol). Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA was then utilized to assess for omnibus differences between exposure groups in continuous confounders, with significant findings followed by Mann-Whitney tests for pairwise contrasts (See Table 1). Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used, as appropriate, for discrete confounders. Potential confounders were also evaluated for associations with each cortisol outcomes (baseline, AUC) in corresponding regression models (See Tables 3 and 4). GA at birth and maternal depressive symptoms were found to be significant confounders for baseline cortisol, while GA at birth and alcohol use were significant confounders for AUC cortisol.

Table 1.

Maternal and infant characteristics, overall and by exposure group

| Total (n=111) | Controls (n=42) | TOB (n=45) | MJ+TOB (n=24) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or% | Mean (SD) or % | |

| Maternal Characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 25 (5) | 25 (6) | 24 (4) | 25 (4) |

| Race/Ethnicity (% Non-Hispanic White) | 46% | 42% | 53% | 42% |

| Low SES1 | 40% | 20% | 47% | 65% *** |

| Gravida | 2.6 (1.8) | 2.3 (1.6) | 2.9 (2.2) | 2.6 (1.4) |

| Parity | 1.1 (1.4) | 1.0 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.5) | 1.1 (1.4) |

| 1st Prenatal Visit (GA in weeks) | 10 (5) | 10 (4) | 10 (5) | 11 (5) |

| Weight gain (pounds)2 | 31 (17) | 33 (17) | 27 (18) | 32 (13) |

| Gestational Medical Conditions3 | 15% | 7% | 22% | 17% |

| Depressive Symptoms4 | 4 (5) | 2 (3) | 5 (5) | 6 (6) ** |

| Maternal Substance Exposure | ||||

| Alcohol Use (>1 drink/week) | 5%* | 0% | 4% | 17% * |

| Caffeine Use (>200 mg/day caffeine)5 | 22% | 5% | 39% | 21% *** |

| ETS Exposure (>1 hour/day)6 | 40% | 2% | 59% | 29% *** |

| Tobacco Use (cigs/day)7 | --- | 0 (0) | 7.3 (6.2) | 6.8 (5.4) |

| Cotinine per day (ng/mL)7 | --- | 0 (0) | 96 (111) | 75 (91) |

| Infant Characteristics | ||||

| Sex (% female) | 46% | 40% | 51% | 46% |

| Delivery Mode (% vaginal delivery) | 77% | 76% | 78% | 79% |

| GA at birth (weeks) | 40 (1) | 40 (1) | 40 (1) | 40 (1) |

| Small for GA8 | 5% | 2% | 7% | 4% |

| Apgar score (> 8 at 5 minutes) | 95% | 90% | 98% | 96% |

| Any breastfeeding | 62% | 81% | 56% | 46% ** |

| ETS Exposure: saliva cotinine (ng/ml)9 | 8 (18) | 1 (2) | 12 (21) | 11 (23)* |

NOTE:

p<.05;

p<.01,

p<.001.

Based on a score of 4 or 5 on the Hollingshead Index.

Weight gain in pounds between pre-pregnancy and 35±1 weeks.

e.g., gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes.

Score on 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

Equivalent of two cups of coffee per day.

Hours of ETS exposure per week measured by structured interview.

No significant differences between tobacco-only and marijuana+tobacco groups

Birthweight <10th percentile for gestational age.

Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS) exposure measured by infant saliva cotinine (ng/ml).

Table 3.

Impact of marijuana and tobacco co-use (TOB+MJ) and tobacco-only use (TOB) on infant baseline cortisol over the first postnatal month overall and by sex.

| Predictor Variable | Overall (n=106, m=592) | Males (n=57, m=328) | Females (n=49, m=264) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | P | β | SE | P | β | SE | P | |

| Intercept | 1.171 | .211 | <001 | 1.670 | .362 | <.001 | .576 | .405 | .156 |

| Infant age (hours)1 | −.254 | .028 | <001 | −.298 | .037 | <.001 | −.203 | .041 | <.001 |

| Time since feeding (mins)1 | −.191 | .048 | <001 | −.259 | .064 | <.001 | −.138 | .072 | .057 |

| Gestational Age (weeks)2 | −.076 | .033 | .021 | −.124 | .039 | .001 | .039 | .062 | .532 |

| Depression Score3 | −.018 | .008 | .034 | −.005 | .012 | .681 | −.020 | .012 | .102 |

| TOB | .007 | .089 | .933 | .011 | .118 | .923 | .022 | .139 | .877 |

| TOB + MJ | −.161 | .107 | .131 | −.436 | .146 | .003 | .092 | .158 | .561 |

| TOB + MJ vs. TOB | −.169 | .103 | .103 | −.447 | .141 | .002 | .071 | .149 | .636 |

NOTE: Baseline cortisol was natural log transformed. Reference group is unexposed control. Red font depicts differences between MJ+TOB compared to TOB-only infants. Bold font indicates statistically significant results for variables of interest at p < .05.

n indicates number of infants; m indicates number of repeated measures across infants.

Infant age was measured in hours, and time since feeding was measured in minutes. Both variables were natural log-transformed.

Gestational Age was centered at 39 weeks.

Score on 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

Table 4.

Impact of marijuana and tobacco co-use (TOB+MJ) and tobacco-only use (TOB) on infant cortisol reactivity (AUC Cortisol) over the first postnatal month overall and by sex

| Predictor Variables | Overall (n=103, m=381) | Males (n=57, m=207) | Females (n=46, m=174) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | P | β | SE | P | β | SE | P | |

| Intercept | 3.836 | .281 | <001 | 3.994 | .400 | <001 | 3.718 | .409 | <.001 |

| Infant age (hours)1 | −.159 | .029 | <001 | −.163 | .040 | <001 | −.158 | .042 | <.001 |

| Time since feeding (mins)1 | .205 | .048 | <001 | .170 | .067 | .012 | .222 | .071 | .002 |

| Gestational Age (weeks)2 | −.068 | .032 | .034 | −.090 | .041 | .030 | −.022 | .059 | .709 |

| Alcohol Use (>1 drink/week) | .512 | .188 | .007 | .655 | .307 | .034 | .483 | .241 | .047 |

| Baseline cortisol (linear) | .680 | .062 | <001 | .681 | .084 | <001 | .688 | .095 | <.001 |

| Baseline cortisol (quadratic) | .167 | .029 | <001 | .162 | .039 | <001 | .191 | .045 | <.001 |

| TOB | −.244 | .084 | .004 | −.145 | .110 | .188 | −.351 | .139 | .012 |

| TOB + MJ | −.250 | .112 | .026 | −.362 | .158 | .023 | −.168 | .174 | .336 |

| TOB + MJ vs. TOB | −.006 | .103 | .956 | −.217 | .155 | .163 | −.183 | .146 | .212 |

Note: AUC cortisol was natural log transformed. Reference group is unexposed control. Red font depicts differences between MJ+TOB compared to TOB-only infants. Bold font indicates statistically significant results for variables of interest at p < .05.

n indicates number of infants, m indicates number of repeated measures across infants.

Infant age was measured in hours, and time since feeding was measured in minutes. Both variables were natural log-transformed.

Gestational Age was centered at 39 weeks.

Score on 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

2.6.1. Sex-specific analyses

All associations were investigated in an overall model including all participants, and in identical models stratified by infant sex. Significant confounders from the overall sample were also utilized for sex-stratified models. As the study was not originally powered to detect sex-specific effects, results are presented for both the combined and sex-stratified samples, even when the corresponding interaction test did not attain statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Descriptive statistics for the overall sample and stratified by substance-exposure group (MJ+TOB, TOB, Controls) are presented in Table 1. The final sample for the present analyses included 111 mothers (mean age 25, SD=5) and their healthy, singleton infant offspring. The sample primarily consisted of racially/ethnically diverse (54% minorities: 18% Black, 25% Hispanic, and 11% Multiracial/Other; 46% Non-Hispanic White), low SES mothers who were not married (75%) and reported that their pregnancies were not planned (82%). On average, the sample presented for their first prenatal care visit at 10 weeks GA (SD=5). Infants ranged in age from 0–43 days over the follow-up period. Average gestational age was 40 (SD=1) weeks, average birth weight was 3360 (SD =472) grams, and average 5-minute Apgar score was 9.

MJ+TOB and TOB-users were more likely to be low SES, to be exposed to ETS, and to be depressed versus Controls (ps<.02). MJ+TOB users were more likely to report alcohol use than Controls (p<.02), while TOB-only users were more likely to report caffeine use versus Controls. Exposure groups did not differ significantly in maternal age, race/ethnicity, gravida/ parity, weight gain, prenatal care, or gestational medical conditions. There were no significant differences in average cigarettes per day (CPD) or maternal cotinine levels between TOB and MJ+TOB users. Infants of MJ+TOB, TOB, and Control mothers did not differ significantly by sex, delivery mode, gestational age, or Apgar score. However, MJ+TOB-exposed and TOB-exposed infants were less likely to be breast-fed than unexposed infants. In addition, MJ+TOB-exposed and TOB-exposed infants showed increased ETS exposure (quantified by saliva cotinine) versus unexposed infants (p <.05).

Rates and frequency of use of TOB and MJ use across pregnancy and for each trimester are shown in Table 2. MJ+TOB users reported an average of 24 (SD=24) days of MJ use across pregnancy. Specifically, they reported M = 24 (SD = 24) days of use in 1st trimester, M = 0.5 (SD = 1) day of use in 2nd trimester, and M = 0.04 (SD = 0.20) days of use in 3rd trimester. Of those reporting MJ use on the TLFB (21/24 participants in the MJ+TOB group), 100%, 29%, and 5% reported use of any MJ during 1st, 2nd, and 3rd trimester, respectively. No between-group differences emerged for either frequency of TOB use across pregnancy (M=207 (SD=101) days of use for the MJ+TOB group vs. M =199 (SD=101) days of use for the TOB-only group, ps = ns) or percentage reporting any TOB use in each trimester (100%, 83%, 83% for 1st, 2nd, and 3rd trimester for the MJ+TOB group and 100% 82% and 73% for the TOB-only group, ps=ns). Finally, MJ+TOB and TOB users also reported similar levels of cigarette use per day across pregnancy (ps = ns). MJ+TOB users reported an average of 10 (SD=8), 6 (SD=6), and 4 (SD=4) cigarettes per day across trimesters; TOB-only users reported an average cigarettes per day of 10 (SD=7), 6 (SD=6), and 5 (SD=6) across trimesters (ps=ns).

Table 2.

Tobacco and marijuana use over pregnancy by exposure group

| Controls (n=42) | TOB (n=45) | MJ+TOB (n=24) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Using1 M(SD); Range | % Using1 M(SD); Range | % Using1 M(SD); Range | |

| Pregnancy | |||

| Tobacco | 0% | 100% | 100% |

| Days of Use2 | --- | 199 (101); 3–292 | 207 (101); 12–289 |

| Marijuana | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Days of Use2 | --- | 24 (24); 0–903 | |

| Trimester 1 | |||

| Tobacco | 0% | 100% | 100% |

| Days of Use2 | --- | 77 (28); 3–91 | 76 (27); 12–91 |

| Marijuana | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Days of Use2 | --- | --- | 24 (24); 0–90 |

| Trimester 2 | |||

| Tobacco | 0% | 82% | 83% |

| Days of Use2 | --- | 72 (45); 0–105 | 81 (43); 0–105 |

| Marijuana | 0% | 0% | 38% |

| Days of Use2 | --- | --- | 0.5 (1); 0–5 |

| Trimester 3 | |||

| Tobacco | 0% | 73% | 83% |

| Days of Use2 | --- | 51 (38,0–96) | 57 (34, 0–95) |

| Marijuana | 0% | 0% | 17% |

| Days of Use2 | --- | --- | 0.04 (0.2); 0–1 |

% Users based on either maternal report of TOB/MJ in the Timeline Followback (TLFB) Interview or positive biomarker.

Days of Use based on maternal report from Timeline Followback (TLFB) Interview.

NOTE. Range includes values of 0 days of use for 3 participants who reported no MJ use on the TLFB but had a positive meconium biomarker test.

3.2. Impact of MJ+TOB and TOB-exposure on baseline cortisol over the first postnatal month.

3.2.1. Overall sample

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 1, after control for significant confounders (GA at birth and maternal depression), there was no significant impact of exposure group on baseline cortisol in overall analyses (F(2,585) =1.52, p=.22). In follow-up pairwise comparisons, although not reaching statistical significance, MJ+TOB and TOB-exposed infants showed some attenuation in baseline cortisol versus unexposed infants (ps=.13 and .103). A significant impact of infant age emerged translating to an 81% decrease in baseline cortisol over the first postnatal month (95% CI=73%−87%; p<.001). No significant interactions emerged between infant age and exposure group (F(2,583) =.58, p=.56).

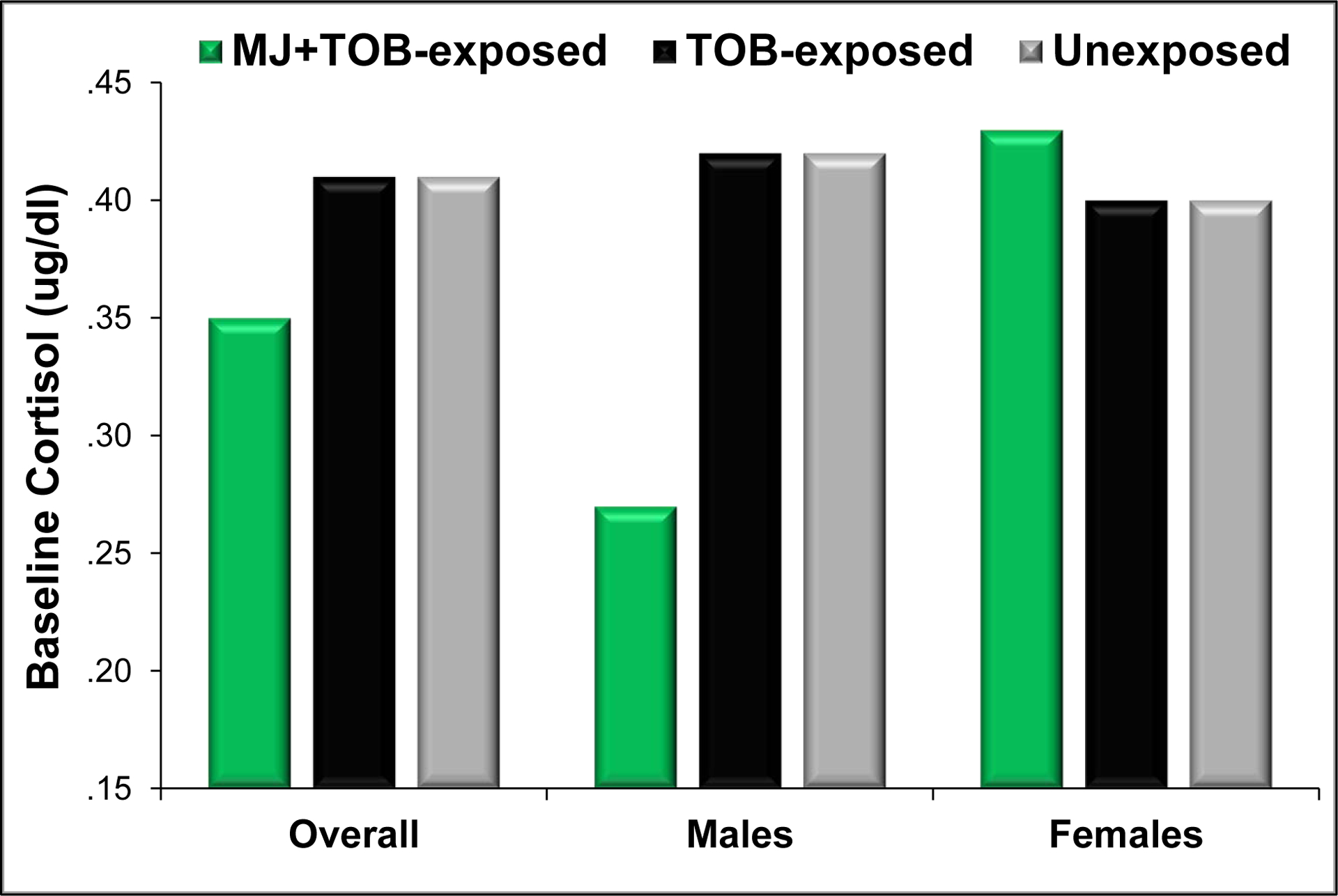

Figure 1.

Mean baseline cortisol over the first postnatal month for MJ+TOB-exposed, TOB-exposed, and unexposed infants in the overall sample and for males and females.

NOTE: Values represent model predictions from a longitudinal regression model for infant baseline cortisol over the first postnatal month with covariates estimated as: postnatal day 5, 60 minutes post-feeding, 40 weeks GA, median depression levels (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale Score = 3).

3.2.2. Sex-specific Effects

As shown in Figure 1, a significant exposure group by infant sex interaction emerged (F(2,582) =3.17, F=.043), such that significant exposure effects were evident among male infants (F(2,321) =5.75, p=.003), but not females (F(2,257) =.18, p=.83). Follow-up pairwise contrasts revealed that MJ+TOB-exposed males showed 35% attenuation in baseline cortisol levels compared to unexposed males (95% CI=14%−51%, p=.003) and 36% attenuation versus TOB-exposed males (95% CI=16%−51%, p=.002). No significant differences emerged between TOB-exposed and unexposed male infants (F(1,321) =.01, p=.92).

3.3. Impact of MJ+TOB and TOB-exposure on cortisol stress response over the first postnatal month.

3.3.1. Overall Sample

As shown in Table 4 and Figure 2, in the overall sample, after control for significant confounders (GA at birth, maternal alcohol use, baseline cortisol), significant exposure group effects emerged in overall analyses (F(2,372) =4.70, p=.001). Specifically, both MJ+TOB and TOB-exposed infants showed a 22% attenuation in cortisol reactivity vs. unexposed infants (MJ+TOB: 95% CI=3%−37%, p=.026; TOB-exposed: 95% CI=8%−34%, p=.004). No significant differences in cortisol reactivity were evident between MJ+TOB and TOB-exposed infants (F(1,372) <.01, p=.96). A significant impact of infant age also emerged, translating to a 2/3 decrease in cortisol reactivity over the first postnatal month (Attenuation=65%, 95% CI=49%−76%, p<.001). No significant interactions between exposure group and infant age were evident (F(2,370) =0.42, p=.65).

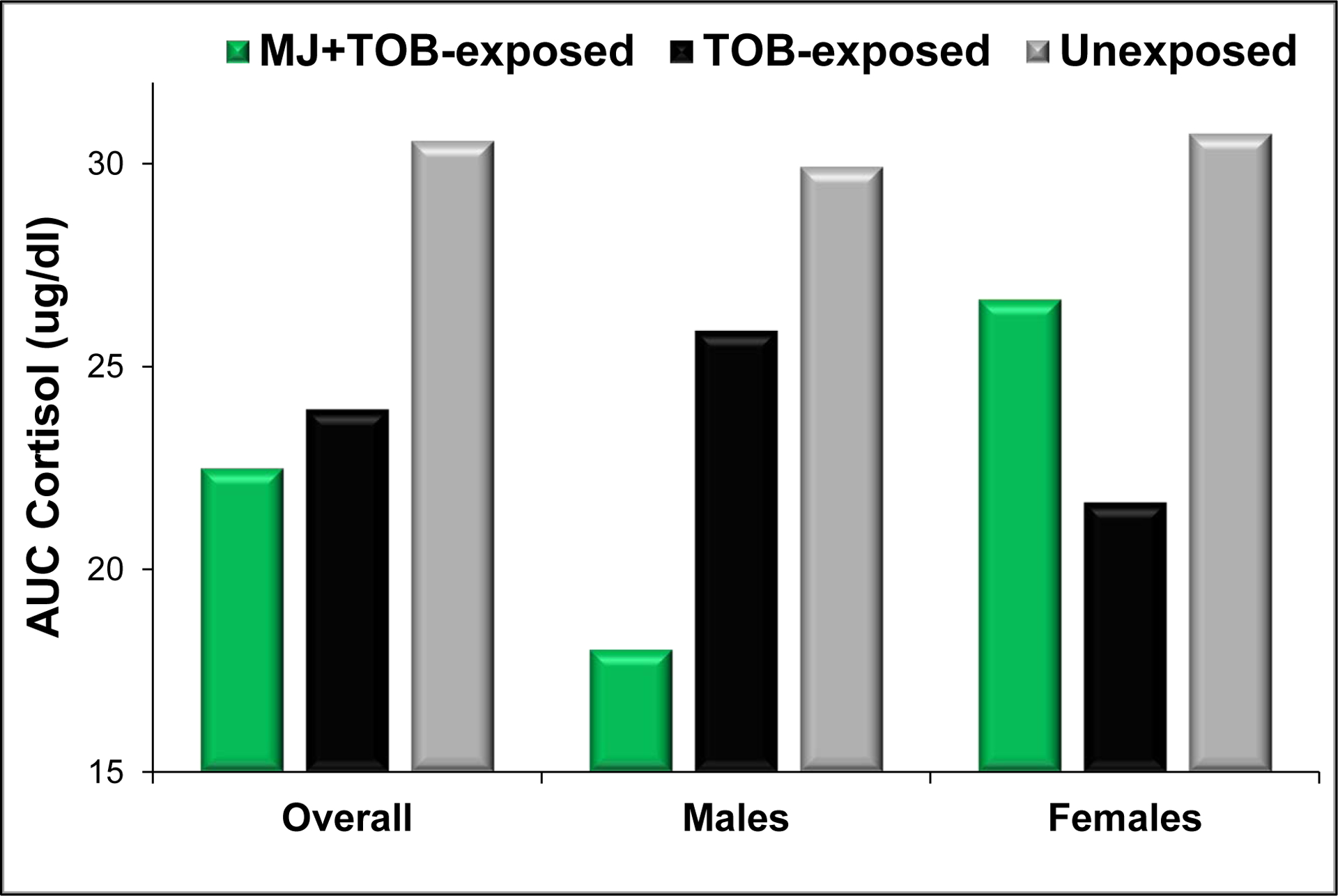

Figure 2.

Mean cortisol reactivity (area under the curve) over the first postnatal month for MJ+TOB-exposed, TOB-exposed, and unexposed infants in the overall sample and for males and females.

NOTE: Values represent model predictions from a longitudinal regression model for infant cortisol reactivity (area under the curve) over the first postnatal month with covariates estimated at: postnatal day 5, 60 minutes post-feeding, 40 weeks GA, < 1 drink per week, and baseline cortisol estimated as shown in Figure 1.

3.3.2. Sex-specific Effects

Although the overall interaction between exposure group and infant sex was not significant (F(2,368) =1.80, p=.17), as shown in Figure 2, sex-stratified analyses revealed that cortisol reactivity (AUC) was 30% attenuated for MJ+TOB-exposed versus unexposed male infants (95% CI=5%−49%, p=.023), whereas no significant differences emerged between TOB-exposed and unexposed males. Among female infants, the opposite pattern emerged, with cortisol reactivity attenuated by 30% for TOB-exposed versus unexposed females (95% CI=8%−46%, p=.012), but no significant differences were evident between MJ+TOB exposed and unexposed females.

4. Discussion

We investigated the impact of marijuana and tobacco (MJ+TOB) co-use during pregnancy on newborn cortisol stress response over the first postnatal month--a measure of biological response to simulated daily handling/daily stressors. We found sex-specific associations between MJ+TOB exposure and offspring baseline cortisol. In particular, MJ+TOB-exposed males showed significantly decreased baseline cortisol versus TOB-exposed and unexposed males, while for females, there were no differences between exposure groups. For cortisol stress response, both MJ+TOB-exposed and TOB-exposed infants showed significantly decreased cortisol response to handling (reactivity) versus unexposed infants. In post-hoc, exploratory sex-specific analyses, MJ+TOB-exposure was associated with decreased cortisol reactivity in males, while TOB-only exposure was associated with decreased cortisol reactivity in females.

To our knowledge, the present study provides the first evidence that prenatal MJ exposure “programs” offspring HPA regulation in humans. Specifically, prenatal MJ+TOB exposure was associated with a 36% decrease in baseline cortisol across the first postnatal month versus TOB-exposure alone and a 35% decrease in baseline cortisol vs. no substance exposure in male offspring. Results—for the most part--complement prior animal models of prenatal THC or cannabinoid agonist exposure, in which prenatal exposure was associated with persistent alterations in offspring HPA regulation into adulthood. Specifically, prenatal THC or cannabinoid agonist exposure was associated with reduced corticosterone levels in male offspring (similar to the current study) (del Arco et al., 1999; Rubio et al., 1998; Rubio et al., 1995), while prenatal THC was associated with increased basal corticosterone levels in female offspring (Rubio et al., 1998; Rubio et al., 1995) (different from the current study). Findings also parallel preclinical studies revealing links between central and peripheral HPA and endocannabinoid systems (Micale and Drago, 2018), and human studies in non-pregnant adults highlighting alterations in HPA regulation following acute and chronic MJ use (Cservenka et al., 2018). Prenatal MJ+TOB exposure was also associated with a 22% attenuation of cortisol stress response vs. no substance exposure--driven by a 30% decreased cortisol stress response in males in post-hoc exploratory analyses. However, there were no differences between effects of prenatal MJ+TOB and those of prenatal TOB exposure (also associated with a 22% attenuation of cortisol stress response vs. no substance exposure). Similar attenuation of offspring cortisol reactivity between MJ+TOB and TOB exposure groups suggests that “programming” effects of prenatal MJ are stronger for basal (versus reactive) cortisol regulation. These results complement animal models, in which effects of prenatal THC/cannabinoid agonist exposure on corticosterone reactivity were inconsistent--one study revealed attenuated ACTH but increased corticosterone response to a place preference test in THC-exposed males (Rubio et al., 1998); another reported increased corticosterone reactivity to a cannabinoid agonist following low dose cannabinoid agonist exposure but attenuated reactivity following high dose prenatal cannabinoid agonist exposure (del Arco et al., 1999).

Sex-specific effects of prenatal MJ+TOB were documented over the first postnatal month--with evidence for greater impact of MJ+TOB co-exposure on male offspring. For basal cortisol, significant associations with prenatal MJ+TOB exposure were evident only for male offspring, while no associations were found in females. In post-hoc exploratory cortisol stress reactivity analyses, significant associations with prenatal MJ+TOB-exposure were evident for males, while associations with TOB-only exposure emerged in females. Although results are preliminary, they complement a large literature documenting sexual dimorphism along multiple prenatal programming pathways in human and preclinical models (Bale, 2011; Carpenter et al., 2017; DiPietro et al., 2011; Gifford and Reynolds, 2017; Sandman et al., 2013; Sundrani et al., 2017). Most relevant to the current study, in a systematic review of sex differences in programming of the HPA axis, although studies were heterogenous, exposure to prenatal stressors was associated with increased cortisol reactivity in females, but altered basal cortisol levels in males (Carpenter et al., 2017). Our finding of more pronounced alteration in baseline vs reactive cortisol in males following exposure to prenatal MJ+TOB is consistent with this review. In contrast, the lack of significant associations between prenatal MJ+TOB and cortisol reactivity in female offspring is not consistent with this review. Finally, our findings also complement an animal model of prenatal THC exposure, in which effects of prenatal THC exposure in adult offspring differed by sex; males showed attenuated basal corticosterone (similar to the current study) but females showed increased basal corticosterone (Rubio et al., 1995) (different from current study). Sex-specific effects also emerged in two human studies of prenatal TOB exposure. In these studies, there was a significant interaction of prenatal smoking group and infant sex such that effects of prenatal TOB on infant cortisol reactivity were significant for infant males but not females at 7 months (increased reactivity) and 9 months (attenuated reactivity) (Eiden et al., 2015; Schuetze et al., 2008).

Although male-specific effects of prenatal MJ+TOB complement prior animal models of prenatal THC exposure and human studies of prenatal TOB exposure, they are in contrast to some theories and empirical reviews of sex differences in prenatal stress exposure in which greater vulnerability in females is described (Carpenter et al., 2017; Sandman et al., 2013). For example, Sandman et al. (2013) proposed that in response to prenatal adversity, males would show more extreme morbidity and mortality (viability), while females would demonstrate a more flexible response associated with improved viability, but increased vulnerability to subtle alterations associated with female-specific disorders in later life (e.g., affective disorders). In support of this theory, analyses across multiple human studies revealed associations between increased maternal glucocorticoid exposure and increased risk for motor and maturational deficits in male offspring, but altered behavior and regional brain development in female offspring (Sandman et al., 2013). Extending this evidence base, Carpenter et al. (2017) found evidence for greater vulnerability in female offspring to alterations in HPA reactivity and placental glucocorticoid regulation following a variety of prenatal exposures, including asthma, stress, prenatal glucocorticoids, and low birth weight and preterm birth. Contrasting results between male vulnerability in the current study and female vulnerability in prior reviews may be due to the focus of prior reviews on prenatal adversity and glucocorticoid exposures, whereas the present study focused on exposure to prenatal substance use. Given known maturational alterations in HPA regulation across development (Gunnar et al., 2009; Lewis and Ramsay, 1995; Tarullo and Gunnar, 2006), it is also possible that contrasting results may be due to our focus on cortisol regulation in the neonatal period versus the focus of Carpenter et al on cortisol regulation in later infancy, childhood, and young adulthood. Finally, in Carpenter et al., female vulnerability was most pronounced in relation to cortisol reactivity whereas, paralleling the current study, there was some evidence for male-specific alterations in basal cortisol regulation following stress.

Intriguingly, sex-specific results from the present study also diverge from our prior study in the same cohort investigating effects of MJ+TOB on newborn neurobehavior over the first month (Stroud et al., 2018b). In our prior study, effects of prenatal MJ+TOB exposure were more pronounced for female offspring across a range of behaviors, including self-soothing, need for external soothing, attention to stimuli, and lethargic behaviors, while effects of TOB exposure alone were more pronounced for males. In the present study, effects of MJ+TOB exposure were more pronounced for males for basal cortisol and in exploratory analyses of cortisol reactivity, while exploratory analyses revealed that effects of TOB exposure alone were more pronounced for females for cortisol reactivity only. Although sex-specific results from both studies are preliminary, they suggest that sexual dimorphism in the impact of MJ+TOB exposure differs by offspring outcome--with more pronounced effects on behavior in females (see also (Godleski et al., 2018), but on HPA regulation in males.

There are several potential mechanisms underlying both overall and sex-specific effects of MJ and MJ+TOB on offspring HPA regulation. Preclinical studies highlight the plausibility of disruption of fetal endocannabinoid signaling pathways as a potential mechanism linking prenatal MJ exposure to alterations in offspring neurodevelopment (Tortoriello et al., 2014). THC crosses the placenta and the blood-brain barrier and binds to receptors in the endocannabinoid system (Bailey et al., 1987; Grotenhermen, 2003; Richardson et al., 2016; Schou et al., 1977). Given reciprocal interactions between the endocannabinoid and HPA signaling systems in non-pregnant adults (Micale and Drago, 2018) and initial evidence of associations between prenatal THC and altered HPA regulation in animal models (Rubio et al., 1998; Rubio et al., 1995), it is possible that prenatal exposure to THC disrupts the developing fetal endocannabinoid signaling system, as well as or leading to enduring changes in HPA regulation in offspring (Franks et al., 2019). In support of this hypothesis, a preclinical study revealed that modulation of endocannabinoid signaling altered HPA stress response/glucocorticoid fast feedback in neonatal rat pups (Buwembo et al., 2013). Given parallel reciprocal interactions between nicotinic cholinergic and HPA signaling pathways, we can also speculate that there are synergistic effects of prenatal MJ/THC and TOB/nicotine on offspring HPA regulation as well as epigenetic pathways (Balkan and Pogun, 2018; Morris et al., 2011). Sex specific effects may be mediated by sex-specific transcriptional regulation, sex differences in placental structure and function that alter maternal-fetal passage of THC and nicotine, sex differences in cannabinoid receptor density in the developing fetal brain, and/or differential impact of sex hormones on the developing fetal brain (Bara et al., 2018; Clifton, 2010; Sundrani et al., 2017).

Although no significant interactions emerged between infant age and MJ/TOB groups, main effects of infant age on both baseline cortisol and reactive cortisol were statistically significant. Specifically, we found a 4/5 decrease in baseline cortisol and a 2/3 decrease in cortisol reactivity over the course of the first postnatal month. Future studies are needed to determine if effects are due to an influence of maturation on both basal and reactive cortisol (Gunnar et al., 2009; Lewis and Ramsay, 1995; Tarullo and Gunnar, 2006), recovery from the immediate acute effects of labor and delivery and the hospital environment (Miller et al., 2005), or habituation to repeated stress testing (Gunnar, 1989; Gunnar et al., 1989).

4.1. Implications and Future Directions

Due to a historical lack of inclusion of females in preclinical and clinical research and evidence for sex differences in disease presentation, considering “sex as a biological variable” at multiple stages of research--including design, analysis, and reporting for both human and animal studies--is now required by studies receiving funding from the National Institute of Health (Clayton, 2018). In the area of prenatal substance exposure, it is critical for studies to--at a minimum—publish findings stratified by sex. In addition, future, large-scale studies are needed to investigate sex-specific effects of prenatal exposure to single and multiple substances on specific, narrow-band phenotypes over development (Wakschlag et al., 2018). Finally, given evidence for sex differences in prevalence and presentation of disease/disorders, studies of sex-specific mechanistic pathways from prenatal exposure to narrow-band phenotype to disease/disorder may aid in discovery of targets for personalized intervention and prevention efforts.

Although the clinical implications of attenuated basal cortisol and cortisol stress response over the first postnatal month are not known, low basal cortisol and failure to mount an adequate cortisol response to daily stressors may be a marker or mechanism underlying risk for stress-related disease (Heim et al., 2000; Raison and Miller, 2003). The present study focused on post-birth changes in stress response during the first postnatal month only. Critical future work in this area is needed to investigate the impact of prenatal TOB+MJ co-exposure on cortisol stress response and neurobehavior over development. Our results also highlight the importance of screening for MJ co-use in pregnant TOB users, education for pregnant TOB users regarding potential risks of MJ co-use, and development of interventions targeted to pregnant co-users.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

There are a number of methodological strengths of the present study, including: (1) comprehensive phenotypic characterization of mothers and newborns. Prenatal MJ and TOB were measured both by calendar-based interview to facilitate recall as well as biochemical verification of (non) use; infant baseline cortisol and cortisol stress response were measured at seven sessions across the first postnatal month, with 4 saliva samples collected at each session to determine reactivity; multiple potential covariates/confounders were measured by maternal interview and medical chart review. Additional strengths include (2) the low-income, racially/ethnically diverse sample and (3) lack of differences in levels of TOB use and nicotine biomarkers between MJ+TOB and TOB groups.

However, we acknowledge important limitations that offer potential directions for future research. In particular, the present study focused on dichotomized prenatal MJ/TOB exposure variables, rather than investigating associations with quantity/frequency of prenatal MJ exposure as both the number of MJ+TOB co-users (N=24) and the frequency of MJ use (average of 24 days of use over pregnancy) were low. Furthermore, the majority of MJ use took place during first trimester (Table 2), which may explain discrepancies in findings between our study and prior animal studies of prenatal THC exposure. That we documented effects of prenatal MJ+TOB on offspring HPA regulation despite the small number of users, low levels of use, and early gestational timing of use highlights strength of effects and the need for future larger-scale studies. In particular, future studies that include an MJ-only group and that are designed to have power to investigate dose response associations between quantity/frequency and timing of prenatal MJ exposure and alterations in offspring cortisol regulation are needed to better distinguish effects of prenatal MJ from those of prenatal TOB. Such studies will be critical both to elucidate mechanisms underlying the impact of prenatal MJ exposure and to educate pregnant women and obstetric and pediatric providers. In addition, the present study was not designed or powered to investigate sex differences in effects of prenatal exposure. Thus, although effects are intriguing and may be hypothesis-generating for future research, larger-scale studies are critical for the field to determine if the present findings will replicate. Finally, although we statistically controlled for relevant demographic differences between MJ+TOB, TOB, and control groups, it is possible that there were unmeasured genetic or personality differences that may lead to both maternal MJ+TOB co-use and alterations in infant HPA regulation. Future studies with genetically sensitive designs are needed (Bidwell et al., 2017; Estabrook et al., 2016).

4.3. Conclusions

The present study is the first to document programming effects of prenatal MJ on offspring glucocorticoid regulation in humans. Exposure to prenatal MJ+TOB (versus prenatal TOB-exposure alone) was associated with 36% attenuated baseline cortisol levels over the first postnatal month in male offspring. Prenatal MJ+TOB exposure was also associated with a 22% decreased in cortisol reactivity over the first postnatal month, similar to effects of prenatal TOB-exposure alone. Complementing some human and preclinical studies, associations between prenatal MJ+TOB exposure and newborn HPA regulation were sex-specific--with most pronounced associations evident in male offspring for baseline cortisol. Future large-scale studies are needed to elucidate molecular mechanisms underlying sex differences in prenatal programming and to characterize sex-specific trajectories leading to sexually dimorphic neurodevelopmental symptoms and disorders.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Prenatal marijuana + tobacco use was linked with diminished infant cortisol levels.

The influence of prenatal marijuana + tobacco differed by infant sex.

Co-exposed male infants showed diminished cortisol; co-exposed females did not.

First human study to show links between prenatal marijuana and offspring cortisol.

Interventions to address marijuana co-use in pregnant tobacco users are needed.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to mothers and infants who contributed to this study, and to the Maternal-Infant Studies Laboratory staff for their assistance with data collection and data management, and to Pamela Borek for administrative assistance.

Role of the funding source

Preparation of this manuscript and data collection was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 DA019558 and R01 DA044504 to L.R.S., and K08 DA045935 to CVL). The funding agencies had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Non-standard Abbreviations:

- TOB

Tobacco

- MJ

Marijuana

- THC

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

- BAM BAM

Behavior and Mood in Babies and Mothers study

- NNNS

NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale

- ETS

environmental tobacco smoke

- CO

carbon monoxide

- SES

socioeconomic status

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Agrawal A, Budney AJ, Lynskey MT, 2012. The co-occurring use and misuse of cannabis and tobacco: a review. Addiction 107(7), 1221–1233.’doi: ‘ 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03837.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JR, Cunny HC, Paule MG, Slikker W Jr., 1987. Fetal disposition of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) during late pregnancy in the rhesus monkey. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 90(2), 315–321.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/0041-008x(87)90338-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale TL, 2011. Sex differences in prenatal epigenetic programming of stress pathways. Stress (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 14(4), 348–356.’doi: ‘ 10.3109/10253890.2011.586447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkan B, Pogun S, 2018. Nicotinic Cholinergic System in the Hypothalamus Modulates the Activity of the Hypothalamic Neuropeptides During the Stress Response. Curr Neuropharmacol 16(4), 371–387.’doi: ‘ 10.2174/1570159X15666170720092442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bara A, Manduca A, Bernabeu A, Borsoi M, Serviado M, Lassalle O, Murphy M, Wager-Miller J, Mackie K, Pelissier-Alicot AL, Trezza V, Manzoni OJ, 2018. Sex-dependent effects of in utero cannabinoid exposure on cortical function. Elife 7.’doi: ‘ 10.7554/eLife.36234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidwell LC, Marceau K, Brick LA, Karoly HC, Todorov AA, Palmer RH, Heath AC, Knopik VS, 2017. Prenatal Exposure Effects on Early Adolescent Substance Use: Preliminary Evidence From a Genetically Informed Bayesian Approach. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 78(5), 789–794.’doi: ‘ 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PA, Grekin ER, Mortensen EL, Mednick SA, 2002. Relationship of maternal smoking during pregnancy with criminal arrest and hospitalization for substance abuse in male and female adult offspring. Am J Psychiatry 159(1), 48–54.’doi: ‘ 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.48 Brown, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Q L, Sarvet AL, Shmulewitz D, Martins SS, Wall MM, Hasin DS, 2017. Trends in Marijuana Use Among Pregnant and Nonpregnant Reproductive-Aged Women, 2002–2014. JAMA 317(2), 207–209.’doi: ‘ 10.1001/jama.2016.17383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buwembo A, Long H, Walker CD, 2013. Participation of endocannabinoids in rapid suppression of stress responses by glucocorticoids in neonates. Neuroscience 249, 154–161.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.10.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter T, Grecian SM, Reynolds RM, 2017. Sex differences in early-life programming of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in humans suggest increased vulnerability in females: a systematic review. J Dev Orig Health Dis 8(2), 244–255.’doi: ‘ 10.1017/S204017441600074X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabarria KC, Racusin DA, Antony KM, Kahr M, Suter MA, Mastrobattista JM, Aagaard KM, 2016. Marijuana use and its effects in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 215(4), 506 e501–507.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Radwan MM, Majumdar CG, Church JC, Freeman TP, ElSohly MA, 2019. New trends in cannabis potency in USA and Europe during the last decade (2008–2017). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 269(1), 5–15.’doi: ‘ 10.1007/s00406-019-00983-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton JA, 2018. Applying the new SABV (sex as a biological variable) policy to research and clinical care. Physiol Behav 187, 2–5.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton VL, 2010. Review: Sex and the human placenta: mediating differential strategies of fetal growth and survival. Placenta 31 Suppl, S33–39.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman-Cowger VH, Oga EA, Peters EN, Mark K, 2018. Prevalence and associated birth outcomes of co-use of Cannabis and tobacco cigarettes during pregnancy. Neurotoxicol Teratol 68, 84–90.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.ntt.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman-Cowger VH, Schauer GL, Peters EN, 2017. Marijuana and tobacco co-use among a nationally representative sample of US pregnant and non-pregnant women: 2005–2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health findings. Drug Alcohol Depend 177, 130–135.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles CD, Kable JA, Lynch ME, 2012. Examination of gender differences in effects of tobacco exposure, in: Lewis M, Kestler L (Eds.), Gender differences in prenatal substance exposure. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Cservenka A, Lahanas S, Dotson-Bossert J, 2018. Marijuana Use and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Functioning in Humans. Front Psychiatry 9, 472.’doi: ‘ 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin SC, Matthews TJ, 2016. Smoking Prevalence and Cessation Before and During Pregnancy: Data From the Birth Certificate, 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep 65(1), 1–14.’ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custodio RJ, Junior CE, Milani SL, Simoes AL, de Castro M, Moreira AC, 2007. The emergence of the cortisol circadian rhythm in monozygotic and dizygotic twin infants: the twin-pair synchrony. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 66(2), 192–197.’doi: ‘ 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02706.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Genna NM, Goldschmidt L, Richardson GA, Cornelius MD, Day NL, 2018. Trajectories of pre- and postnatal co-use of cannabis and tobacco predict co-use and drug use disorders in adult offspring. Neurotoxicol Teratol 70, 10–17.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.ntt.2018.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Arco I, Munoz R, Rodriguez De Fonseca F, Escudero L, Martin-Calderon J, Navarro M, Villanua M, 1999. Maternal exposure to the synthetic cannabinoid HU-210: effects on the endocrine and immune systems of the adult male offspring. Neuroimmunomodulation 7(1), 16–26.’ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro JA, Costigan KA, Kivlighan KT, Chen P, Laudenslager ML, 2011. Maternal salivary cortisol differs by fetal sex during the second half of pregnancy. Psychoneuroendocrinology 36(4), 588–591.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake P, Driscoll AK, Mathews TJ, 2018. Cigarette Smoking During Pregnancy: United States, 2016. NCHS Data Brief(305), 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Molnar DS, Granger DA, Colder CR, Schuetze P, Huestis MA, 2015. Prenatal tobacco exposure and infant stress reactivity: role of child sex and maternal behavior. Dev Psychobiol 57(2), 212–225.’doi: ‘ 10.1002/dev.21284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Schuetze P, Shisler S, Huestis MA, 2018. Prenatal exposure to tobacco and cannabis: Effects on autonomic and emotion regulation. Neurotoxicol Teratol 68, 47–56.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.ntt.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Marroun H, Hudziak JJ, Tiemeier H, Creemers H, Steegers EA, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Verhulst FC, van den Brink W, Huizink AC, 2011. Intrauterine cannabis exposure leads to more aggressive behavior and attention problems in 18-month-old girls. Drug Alcohol Depend 118(2–3), 470–474.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Marroun H, Tiemeier H, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Mackenbach JP, Steegers EA, Verhulst FC, van den Brink W, Huizink AC, 2008. Demographic, emotional and social determinants of cannabis use in early pregnancy: the Generation R study. Drug Alcohol Depend 98(3), 218–226.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElSohly MA, Mehmedic Z, Foster S, Gon C, Chandra S, Church JC, 2016. Changes in Cannabis Potency Over the Last 2 Decades (1995–2014): Analysis of Current Data in the United States. Biol Psychiatry 79(7), 613–619.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RL, Gregory MP, Grace JL, Levine MD, 2016. Prevalence and correlates of a lifetime cannabis use disorder among pregnant former tobacco smokers. Addict Behav 54, 52–58.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson JG, 2016. Developmental Origins of Health and Disease - from a small body size at birth to epigenetics. Ann Med 48(6), 456–467.’doi: ‘ 10.1080/07853890.2016.1193786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrook R, Massey SH, Clark CA, Burns JL, Mustanski BS, Cook EH, O’Brien TC, Makowski B, Espy KA, Wakschlag LS, 2016. Separating Family-Level and Direct Exposure Effects of Smoking During Pregnancy on Offspring Externalizing Symptoms: Bridging the Behavior Genetic and Behavior Teratologic Divide. Behav Genet 46(3), 389–402.’doi: ‘ 10.1007/s10519-015-9762-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ, 1998. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and psychiatric adjustment in late adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55(8), 721–727.’doi: ‘ 10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH, 2011. Applied longitudinal analysis, 2nd ed John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, N.J. [Google Scholar]

- Franks AL, Berry KJ, DeFranco DB, 2019. Prenatal drug exposure and neurodevelopmental programming of glucocorticoid signalling. J Neuroendocrinol, e12786.’doi: ‘ 10.1111/jne.12786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford RM, Reynolds RM, 2017. Sex differences in early-life programming of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in humans. Early Hum Dev 114, 7–10.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godleski SA, Shisler S, Eiden RD, Huestis MA, 2018. Co-use of tobacco and marijuana during pregnancy: Pathways to externalizing behavior problems in early childhood. Neurotoxicol Teratol 69, 39–48.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.ntt.2018.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray TR, Eiden RD, Leonard KE, Connors GJ, Shisler S, Huestis MA, 2010. Identifying prenatal cannabis exposure and effects of concurrent tobacco exposure on neonatal growth. Clin Chem 56(9), 1442–1450.’doi: ‘ 10.1373/clinchem.2010.147876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray TR, LaGasse LL, Smith LM, Derauf C, Grant P, Shah R, Arria AM, Della Grotta SA, Strauss A, Haning WF, Lester BM, Huestis MA, 2009a. Identification of prenatal amphetamines exposure by maternal interview and meconium toxicology in the Infant Development, Environment and Lifestyle (IDEAL) study. Ther Drug Monit 31(6), 769–775.’doi: ‘ 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181bb438e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray TR, Shakleya DM, Huestis MA, 2009b. A liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method for the simultaneous quantification of 20 drugs of abuse and metabolites in human meconium. Anal Bioanal Chem 393(8), 1977–1990.’doi: ‘ 10.1007/s00216-009-2680-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotenhermen F, 2003. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Clin Pharmacokinet 42(4), 327–360.’doi: ‘ 10.2165/00003088-200342040-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, 1989. Studies of the human infant’s adrenocortical response to potentially stressful events. New Dir Child Dev(45), 3–18.’doi: ‘ 10.1002/cd.23219894503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Connors J, Isensee J, 1989. Lack of stability in neonatal adrenocortical reactivity because of rapid habituation of the adrenocortical response. Dev Psychobiol 22(3), 221–233.’doi: ‘ 10.1002/dev.420220304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Malone S, Fisch RO, 1985. The psychobiology of stress and coping in the human neonate: Studies of adrenocortical activity in response to aversive stimulation, in: Field T, McCabe P, Schneiderman N (Eds.), Stress and coping; Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Talge NM, Herrera A, 2009. Stressor paradigms in developmental studies: what does and does not work to produce mean increases in salivary cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology 34(7), 953–967.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada H, Matthews SG, 2019. Prenatal programming of stress responsiveness and behaviours: Progress and perspectives. J Neuroendocrinol 31(3), e12674.’doi: ‘ 10.1111/jne.12674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M, 1960. A rating scale for depression. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 23, 56–62.’doi: ‘ 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslinger C, Bamert H, Rauh M, Burkhardt T, Schaffer L, 2018. Effect of maternal smoking on stress physiology in healthy neonates. J Perinatol 38(2), 132–136.’doi: ‘ 10.1038/jp.2017.172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Lu J, Dong W, Jiao Z, Zhang C, Yu Y, Zhang Z, Wang H, Xu D, 2017. Prenatal nicotine exposure induces HPA axis-hypersensitivity in offspring rats via the intrauterine programming of up-regulation of hippocampal GAD67. Arch Toxicol 91(12), 3927–3943.’doi: ‘ 10.1007/s00204-017-1996-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Ehlert U, Hellhammer DH, 2000. The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of stress-related bodily disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 25(1), 1–35.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/s0306-4530(99)00035-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen LK, Slotkin TA, Mencl WE, Frost SJ, Pugh KR, 2007. Gender-specific effects of prenatal and adolescent exposure to tobacco smoke on auditory and visual attention. Neuropsychopharmacology 32(12), 2453–2464.’doi: ‘ 10.1038/sj.npp.1301398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MJ, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Feyerabend C, Vesey C, Saloojee Y, 1987. Comparison of tests used to distinguish smokers from nonsmokers. Am J Public Health 77(11), 1435–1438.’doi: ‘ 10.2105/ajph.77.11.1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph D, Chong NW, Shanks ME, Rosato E, Taub NA, Petersen SA, Symonds ME, Whitehouse WP, Wailoo M, 2015. Getting rhythm: how do babies do it? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 100(1), F50–54.’doi: ‘ 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Wu P, Davies M, 1994. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and smoking by adolescent daughters. Am J Public Health 84(9), 1407–1413.’doi: ‘ 10.2105/ajph.84.9.1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapaya M, D’Angelo DV, Tong VT, England L, Ruffo N, Cox S, Warner L, Bombard J, Guthrie T, Lampkins A, King BA, 2019. Use of Electronic Vapor Products Before, During, and After Pregnancy Among Women with a Recent Live Birth - Oklahoma and Texas, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68(8), 189–194.’doi: ‘ 10.15585/mmwr.mm6808a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Stroud LR, Paronis CA, 2003. Smoking, stress, and negative affect: correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychol Bull 129(2), 270–304.’doi: ‘ 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko JY, Farr SL, Tong VT, Creanga AA, Callaghan WM, 2015. Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age. Am J Obstet Gynecol 213(2), 201 e201–201 e210.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondracki AJ, 2019. Prevalence and patterns of cigarette smoking before and during early and late pregnancy according to maternal characteristics: the first national data based on the 2003 birth certificate revision, United States, 2016. Reprod Health 16(1), 142.’doi: ‘ 10.1186/s12978-019-0807-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurti AN, Redner R, Lopez AA, Keith DR, Villanti AC, Stanton CA, Gaalema DE, Bunn JY, Doogan NJ, Cepeda-Benito A, Roberts ME, Phillips J, Higgins ST, 2017. Tobacco and nicotine delivery product use in a national sample of pregnant women. Prev Med 104, 50–56.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester BM, Tronick EZ, Brazelton TB, 2004. The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale procedures. Pediatrics 113(3 Pt 2), 641–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Ramsay DS, 1995. Developmental change in infants’ responses to stress. Child Dev 66(3), 657–670.’doi: ‘ 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00896.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Xu G, Rong S, Santillan DA, Santillan MK, Snetselaar LG, Bao W, 2019. National Estimates of e-Cigarette Use Among Pregnant and Nonpregnant Women of Reproductive Age in the United States, 2014–2017. JAMA Pediatr 173(6), 600–602.’doi: ‘ 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Liu F, Kou H, Zhang BJ, Xu D, Chen B, Chen LB, Magdalou J, Wang H, 2012. Prenatal nicotine exposure induced a hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis-associated neuroendocrine metabolic programmed alteration in intrauterine growth retardation offspring rats. Toxicol Lett 214(3), 307–313.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, Drake P, 2018. Births: Final Data for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep 67(8), 1–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald SD, Walker M, Perkins SL, Beyene J, Murphy K, Gibb W, Ohlsson A, 2006. The effect of tobacco exposure on the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. BJOG 113(11), 1289–1295.’doi: ‘ 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehmedic Z, Chandra S, Slade D, Denham H, Foster S, Patel AS, Ross SA, Khan IA, ElSohly MA, 2010. Potency trends of Delta9-THC and other cannabinoids in confiscated cannabis preparations from 1993 to 2008. J Forensic Sci 55(5), 1209–1217.’doi: ‘ 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2010.01441.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micale V, Drago F, 2018. Endocannabinoid system, stress and HPA axis. European journal of pharmacology 834, 230–239.’doi: ‘ 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NM, Fisk NM, Modi N, Glover V, 2005. Stress responses at birth: determinants of cord arterial cortisol and links with cortisol response in infancy. BJOG 112(7), 921–926.’doi: ‘ 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00620.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]