Abstract

Parental alcohol dependence is a significant risk factor for harsh caregiving behaviors; however, it is unknown whether and how harsh caregiving changes over time and across parenting contexts for alcohol-dependent mothers. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no studies have examined whether and how distinct dimensions of child characteristics, such as negative emotionality modulate harsh caregiving among alcohol-dependent mothers. Guided by parenting process models, the present study examined how two distinct domains of children’s negative emotionality – fear and frustration – moderate the association between maternal alcohol dependence and maternal harshness across discipline and free-play contexts. A high-risk sample of 201 mothers and their two-year-old children were studied over a one-year period. Results from latent difference score analyses indicated that harsh parenting among alcohol-dependent mothers increased over time in the more stressful discipline context, but not in the parent-child play context. This effect was maintained even after controlling for other parenting risk factors, including other forms of maternal psychopathology. Furthermore, this increase in harsh parenting was specific to alcohol-dependent mothers whose children were displaying high levels of anger and frustration. Findings provide support for specificity in conceptualizations of child negative emotionality and parenting contexts as potential determinants of maladaptive caregiving among alcohol-dependent mothers.

Keywords: Parental substance abuse, maternal psychopathology, parenting, child temperament, negative emotionality, alcohol dependence

Approximately 1 in 8 children in the United States reside with a parent who has a substance use disorder (Lipari & Van Horn, 2017). Children of parents with substance use disorders are at an increased risk of maladjustment and psychopathology, such as aggression and behavioral problems (Luthar, Cushing, Merikangas, & Rounsaville, 1998), antisocial behavior (Waller et al., 2012), and problematic substance use in adolescence and adulthood (Orford & Velleman, 1990). Additionally, parental substance use disorders have been linked to child internalizing symptomatology, including mood disorders and anxiety (Peleg-Oren & Teichman, 2006). Given the prevalence of parental substance use disorders and their impact on child development, it is imperative to understand the pathways through which parental chemical dependence impacts children. Parenting is one of the most proximal and salient developmental contexts, and thus caregiving behaviors significantly influence developmental trajectories. However, parenting is also adversely affected by chemical dependence (Mayes & Truman, 2002). Thus, maladaptive caregiving may be one significant pathway through which parental substance use disorders undermine child adjustment and facilitates the development of child psychopathology. Specifically, parents struggling with substance use disorders are thought to have negative parenting attitudes (Flykt et al., 2012), display more maladaptive parenting behaviors (Mayes & Truman, 2002), and have poorer relationships with their children (Slesnik, Feng, Brakenhoff, & Brigham, 2014).

Prior research on parental substance abuse has focused on many substances of abuse; however, alcohol is one of the most commonly abused substances, and one of the most readily available (Sussman, Lisha, & Griffiths, 2011). It is important to examine alcohol dependence among mothers given that rates of alcohol dependence among women of childrearing age are steadily increasing (McHugh, Wigderson, & Greenfield, 2014). Furthermore, the detrimental effects of pathological alcohol use are exaggerated among women, which can have significant implications for parenting (Mann et al., 2005). Testifying to this, research has demonstrated that alcohol interferes with many of cognitive processes that facilitate sensitive and supportive parenting among mothers (e.g. Kim et al., 2017). When taken together, these findings underscore the importance of examining the pathways through which maternal alcohol dependence undermines caregiving.

Overall, several studies suggest a strong link between parental substance dependence and harsh, coercive caregiving practices (Famularo, Kinscherff, & Fenton, 1992; Kim, Pears, Fisher, Connelly, & Landsverk, 2010; Miller, Smyth, & Mudar, 1999). Parental harshness is one of the primary antecedents of child maltreatment (Afifi, Mota, Sareen, & MacMillan, 2017) and is broadly linked with maladaptive developmental outcomes, such as child antisocial behavior and aggression (Chang, Schwartz, Dodge, & McBride-Chang, 2003). Nevertheless, the few studies focusing on parental harshness among chemically-dependent parents have yet to investigate harsh childrearing practices via parenting process models and developmental theoretical frameworks. Thus, one of the preliminary aims of this study is to use a developmental process model of caregiving to further understand whether and how maternal alcohol dependence is associated with harsh caregiving. Furthermore, parenting behaviors may manifest and operate differently in distinct childrearing contexts. Hence, although parental aggressiveness is linked with parental substance use disorders (Hien & Honeyman, 2000), it is unknown whether the impact of maternal alcohol dependence may be similar or different across caregiving situations. Thus, this study’s second aim is to examine changes in harsh parenting behaviors over time and across two distinct parenting contexts. Further, process models of parenting emphasize that caregiving behaviors are influenced by the interplay between parent and child characteristics, such as parent psychopathology and child temperament (Belsky, 1984); however, this perspective has not been explicitly examined within the parental substance abuse literature. Therefore, the final aim of this study is to examine whether and how dimensions of child temperament may moderate the relation between parental alcohol dependence and harsh caregiving over time and in different caregiving contexts.

Parenting in the Context of Maternal Alcohol Dependence

Parenting is a dynamic and multifaceted process that features many challenges and stressors (Deater-Deckard, 1998; Strohschein, Gauthier, Campbell, & Kleparchuk, 2008). As such, caregiving behaviors may be influenced by several intertwining factors, namely characteristics of the parent, the child, and the broader familial environment (Abidin, 1992). Specifically, Belsky’s (1984) parenting process model introduces three dimensions that determine caregiving, the first being characteristics of the parent. For alcohol-dependent mothers, alcohol dependence may either deplete or interfere with the psychological resources needed for optimal caregiving (e.g. Kim et al., 2017) such as coping skills needed to successfully navigate the challenges and demands of childrearing, particularly in stressful parenting situations (McCormick & Smith, 1995). Incidentally, impaired or adverse coping strategies may significantly contribute to maternal aggressive behavior (Hien & Honeyman, 2000). Thus, this illustrates one pathway through which maternal alcohol dependence undermines caregiving and facilitates expressions of maternal harsh parenting.

However, the stressors inherent to the parenting role may differ across distinct parenting situations (Deater-Deckard, 1998). In particular, some caregiving contexts may be more or less stressful for parents to navigate. For example, discipline contexts can be inherently stressful for parents given the socialization goals of child compliance and behavioral control in comparison to play contexts in which the socialization goal is affiliative and prosocial. Maternal characteristics may be essential factors that influence caregiving behaviors in more demanding childrearing contexts (Sturge-Apple, Suor, & Skibo, 2014). Research has demonstrated that alcohol dependence may dysregulate neural stress response systems (Rutherford & Mayes, 2017) and reduce distress tolerance (Leyro, Zvolensky, & Bernstein, 2010), thereby increasing maladaptive behavioral coping responses to environmental stressors. Thus, considered within parenting process models, alcohol-dependent mothers may be particularly vulnerable to parenting stressors, especially in stressful caregiving situations. As such, harsh parenting behaviors may be more likely to manifest when parents struggle to effectively regulate stress responses in stressful childrearing contexts such as discipline situations when compared to more benign contexts (Webster-Stratton, 1990). In short, maternal alcohol dependence is one maternal characteristic that compromises sensitive, nurturing, and adaptive caregiving behaviors and can influence the development of harsh parenting practices. Although this link between maternal alcohol dependence and parenting deficits is well documented, less is known about how maternal alcohol dependence predicts parenting difficulties across challenging parenting contexts.

It may be particularly important to examine harsh parenting among alcohol dependent mothers with toddlers. Specifically, early childhood is a critical period for children’s development of core regulatory processes, such as emotion and behavioral regulation (Bronson, 2000). Harsh parenting behaviors, which peak during early childhood (Kim et al., 2010) significantly undermine children’s ability to successfully develop these fundamental capabilities (Hughes & Ensor, 2006). Moreover, parental substance abuse may have a particularly strong negative effect on children’s emotional and behavioral adjustment during this developmental period (Salo & Flykt, 2013), which can increase risk for child psychopathology (for review, see Velleman & Templeton, 2007). Furthermore, parental harshness during early childhood not only affects risk for psychopathology during this developmental period but can also have a lasting effect on adjustment during adolescence and adulthood (Raby, Roisman, Fraley, & Simpson, 2015). When consolidating these notions, it is vital to further understand the association between maternal alcohol dependence and harsh parenting among mothers with young children.

The Moderating Role of Child Negative Emotionality

Research on parenting in the context of maternal alcohol dependence has yet to comprehensively examine other factors that could potentially influence harsh parenting across distinct childrearing situations, such as child characteristics. Parenting process models posit that child factors also aid in determining parenting behaviors in different caregiving contexts (Belsky, 1984). According to these theoretical frameworks, children’s characteristics may moderate the caregiving that they receive (Davidov, Knafo-Noam, Serbin, & Moss, 2015). One such characteristic that has been shown to influence caregiving has been child temperament (i.e. Sturge-Apple, Davies, Martin, Cicchetti, & Hentges, 2012), often defined as biologically-based differences in reactivity and self-regulation (Rothbart & Bates, 1998). Although many studies report main effects of child temperament on parenting (i.e. Gallagher, 2002), few studies have examined the potential moderating role of temperament on parenting from within parenting process models. However, aspects of child temperament have been shown to moderate relations between maternal characteristics – such as maternal personality – and parenting behaviors (Clark, Kochanska, & Ready, 2000; Koenig, Barry, & Kochanska, 2010). Other findings show that child temperamental traits may also moderate associations between parenting and parent’s stress reactivity during parent-child interactions (Martorell & Bugental, 2006; Merwin, Smith & Dougherty, 2015).

Historically, research examining the potentiating role of child temperament in family process models has focused on child negative emotionality, defined as a child’s tendency to react to environmental stimuli with high levels of anger, irritability, fear, or sadness (Rothbart, Ahadi, & Hershey, 1994). Particularly, child negative emotionality has been linked with increased parenting stress (Gelfand, Teti, & Radin Fox, 1992), suggesting that high levels of parenting stress may result in deficits in the provision of sensitive, warm parenting in the presence of child negative emotionality. Given that mothers from at-risk populations exhibit greater deficits in caregiving when stressed (Martorell & Bugental, 2006) and that alcohol dependence significantly interferes with one’s ability to regulate stress, the links between maternal alcohol dependence and harsh parenting may be particularly exaggerated in the presence of child negative emotionality. Although child temperament among children of alcohol-dependent parents has been examined (Peterson Edwards, Leonard, & Eiden, 2001), less is known about the influence of child negative emotionality in caregiving among alcohol-dependent mothers, and whether the interaction between child negative emotionality and maternal alcohol dependence may differ in specific caregiving contexts. To address this gap, the current study examines the moderating role of two dimensions of child negative emotionality in the association between maternal alcohol dependence and harsh parenting within stressful and benign caregiving contexts.

Although commonly examined as one overarching temperamental construct, conceptualizations of negative emotionality have expanded to consider distinct dimensions of emotionality, each serving as behavioral strategies children employ to adapt to environmental stressors (Rothbart et al., 1994). From this perspective, children faced with threat or novelty may respond to distress in two distinct ways. The first, dominant negative emotionality typically refers to defensive affective responses, such as frustration and anger in the face of environmental threat or challenge (Calkins & Johnson, 1998). Specifically, young children of alcohol dependent parents may respond to their maladaptive caregiving environments with expressions of frustration or aggressiveness (Edwards, Eiden, Colder, & Leonard, 2006), therefore this aspect of child emotionality may be a particularly salient temperamental expression to examine within this population of children. Alternatively, expressions of vulnerable negative affect reflect a dimension of negative emotionality in which children respond to stressful external stimuli via expressions of sadness, crying, freezing, and withdrawal. Research has demonstrated that these two dimensions of negative emotionality – dominant negative affect (i.e. frustration) and vulnerable negative affect (i.e. fearfulness) – may operate as distinct temperamental constructs that differentially influence child adjustment (Rothbart et al., 1994); however, few studies have focused on whether and how these dimensions of emotionality moderate caregiving.

To our knowledge, the paucity of studies that have examined children’s emotionality as a moderator between parental characteristics and caregiving behaviors have been concentrated in the maternal personality literature. Although maternal personality is not the focus of our paper, findings from this research area provide some conceptual and predictive utility for examining child emotionality as a moderator of parenting. For example, Coplan and colleagues (2009) found that aspects of maternal personality were strongly negatively associated with harsh parenting among parents of emotionally-dysregulated children. Additionally, a similar study found that mothers with low optimism displayed less positive parenting when parenting difficult, anger-prone children (Koenig et al., 2010). In short, these studies proffer that aspects of children’s negative emotionality may interact with parent characteristics to predict caregiving behavior.

We believe that components of child negative emotionality – frustration and fear – may differentially evoke caregiving behaviors from their parents, thereby operating as a moderator of caregiving in distinct parenting contexts. Specifically, in discipline contexts, children may be more likely to display opposition in reaction to their parents’ demands for behavioral compliance. However, high levels of fearfulness may make children easier to discipline, which may increase child compliance (Kochanska, Coy, & Murray 2001; van der Mark, Bakersmans-Krandenberg, & van Ijzendoorn, 2002). Importantly, if children are easier to discipline and are more likely to comply with their parents’ commands, parents may not need to use frequent or intense harsh discipline tactics to obtain or maintain child compliance. This offers one thought as to how and why child fearfulness may moderate harsh caregiving. Conversely, high levels of child frustration may predict more behavioral and emotional problems (Lengua & Kovacs, 2005; Lengua, 2006; Rothbart & Bates, 2006) which can increase children’s behavioral defiance within discipline contexts. In the presence of these difficulties, parents may find caregiving to be more stressful, difficult, and emotionally challenging (i.e. Pelham et al., 1997). This may, in turn, result in higher levels of harsh parenting. In sum, aspects of child emotionality may moderate caregiving in specific parent-child situations; however, this concept of child factors moderating parenting has been significantly underexplored.

Thus, while research has extensively examined children’s emotional responses to insensitive parenting (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Papp, 2003; Pluess & Belsky, 2010; Solantaus-Simula, Punamäki, & Beardslee, 2002), underexplored is how children’s emotional responses may moderate determinants of caregiving and insensitive parenting. Consequently, less is known about whether parents’ behaviors manifest differently when child emotions are expressed in different intensities and in different caregiving situations. Important for our study, when children express these intense emotions, alcohol-dependent parents may react with heightened levels of maladaptive caregiving, including harsh parenting behaviors. However, no prior study has examined child negative emotionality as a moderator of parenting among chemically dependent mothers. Additionally, to our knowledge, no study has examined relations between distinct components of child negative emotionality and harsh caregiving in the context of maternal alcohol dependence.

The present study.

In sum, maternal alcohol dependence significantly interferes with caregiving behaviors that facilitate positive child adjustment; however, missing from the literature is a thorough integration of developmental theoretical frameworks that examine parenting as a multifaceted process and developmental context. Moreover, less is known about how maternal caregiving practices in the context of alcohol dependence may change over time and across different caregiving situations. Recent theoretical frameworks also suggest that child characteristics may affect caregiving in diverse contexts. The present study is designed to address these important gaps by examining the joint role of maternal alcohol dependence and child negative emotionality as predictors of harsh parenting across childrearing contexts. Moreover, the current study aims to address several methodological and conceptual limitations seen in prior research. First, many studies examining alcohol dependence recruit samples from rehabilitation and psychiatric clinics to ensure variability in the levels and subsequent impacts of substance abuse. However, this excludes parents who may struggle with untreated or undiagnosed chemical dependence (West & Prinz, 1987). Therefore, this study will use a community sample to better understand associations between maternal alcohol dependence and parenting for mothers who are not receiving treatment for their alcohol use disorder. Additionally, prior studies often fail to distinguish between alcohol use, abuse, and dependence (Mayes & Truman, 2002). Thus, this study measure alcohol dependence based on diagnostic criteria which indicate the most significant and debilitating psychological impairments stemming from alcohol abuse (Segal, 2010).

Relatedly, prior studies of substance-abusing mothers have relied on parent reports and hypothetical vignettes of parenting behaviors even though research with other at-risk parenting populations suggest using behavioral observation techniques allow researchers to garner rich, comprehensive, unbiased “snapshots” of parenting in context (Herbers, Garcia, & Obradovic, 2017). Many studies of at-risk parents also focus on physical expressions of parental harshness, even though parental harshness includes both physical and verbal behavior toward the child (Wang & Kenny, 2014). Thus, verbal expressions of harshness among alcohol dependent mothers have been underexplored. Therefore, this study will use behavioral observation coding of physical and verbal maternal harshness during parent-child interactions. Lastly, given a lack of research examining maternal alcohol dependence and caregiving across early childhood, the present study employs a longitudinal research design to examine whether and how processes of caregiving among alcohol-dependent mothers change over time.

Given findings from prior research on parenting and maternal alcohol use disorders (i.e. Miller et al., 1999), we hypothesize that maternal alcohol dependence would predict increases in harsh parenting over time in the more challenging and demanding parenting context relative to the less challenging and demanding parenting context. Guided by contextual models of caregiving and parenting stress, we also hypothesized that this association will be moderated by child temperament characteristics in a manner consistent with diathesis stress frameworks. Given the dearth of research examining how child emotionality may moderate determinants of caregiving, we made no apriori hypotheses with respect to the moderating role of dominant and vulnerable negative affect.

Methods

Data for this project were drawn from a larger 3-year longitudinal study that examined children’s socio-emotional adjustment in the context of interparental conflict. Secondary data analysis included an assessment of maternal alcohol dependence, maternal depression and PTSD symptomatology, and behavioral observation of parenting behaviors and child temperamental traits.

Participants

Participants included 201 two-year old children and their mothers residing in a moderately-sized metropolitan area in the Northeastern United States. Child participants were approximately 26 months old at the first wave of data collection. A two-step recruitment process was utilized to ensure the enrollment of a high-risk sample endorsing an array of psychological risk factors and sociodemographic adversity. The first step entailed recruitment of subjects through agencies serving disadvantaged children and families, including Temporary Assistance to Needy Families rosters obtained from the Department of Health and Human Services, and the county family court system. A truncated version of the Conflict Tactics Scale 2 (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996) was administered in the second step to ensure proportionate distribution of exposure to inter-partner conflict. Other inclusion criteria were that a) the target child’s biological mother was the participating female adult, b) the child participant was approximately 27-months old and without significant developmental delays, and c) mothers’ male relationship partner had regular contact with the mother-child dyad during the year prior to participation.

Median annual income for families was $18,300 per year, and many mothers (30%) and their partners (24%) had not completed secondary education. A substantial percentage of families received public assistance (95%), and nearly all families were impoverished according to the United States Federal Poverty Guidelines (99.5%). The median age for child participants at Wave 1 of data collection was 26 months (SD = 1.69), with 44% of the sample consisting of females. Most of the participants identified as African American (56%), followed by moderate proportions of European American (23%), and smaller percentages of Latino (11%), multiracial (7%), and “other” (3%).

Procedure.

Data for the initial study were collected across three waves, each spaced one apart with the first wave beginning when the child was approximately 2 years of age. For each wave, mother-child dyads made three visits to a research laboratory within a one-to-two-week interval to obtain and complete the study’s assessments, all of which were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board prior to their dissemination. Mothers completed questionnaires and interviews with a member of the research team across the three visits. Additionally, a parent-child free-play/cleanup interaction task was recorded and subsequently coded by a team of independent coders. Procedures were standardized across all participants.

Mother-child free-play and clean-up task.

An unstructured parent-child free-play paradigm was utilized to assess maternal parenting behaviors at each wave. This task was an adaptation of the ABA free-play and clean-up task used in Beeghly and Cicchetti (1994). Specifically, the free-play paradigm resembles a parenting context characterized by low levels of stress, demandingness, and challenge, whereas the cleanup task represents a more stressful parenting situation that also elicits aversive affective states from children. The main reasons why this context is perceived as a more challenging is likely because children often disregard their parent’s instructions to cleanup and mothers are responsible for gaining child compliance in a short amount of time. This mismatch between the mother’s goals and the child’s interests is thought to increase the amount of stress, childrearing demands, and responsibility perceived by the mother. In summary, these parent-child interaction tasks provide an effective framework that adequately contextualizes caregiving in two distinct contexts: benign and challenging parenting situations. Therefore, the use of this conceptual approach allows for a more comprehensive interpretation and understanding on the effects of maternal alcohol dependence on parenting behaviors in different childrearing situations.

Child ‘dominant’ and ‘vulnerable’ negative emotionality.

At Wave 1, children were administered a series of standard temperament paradigms that were designed to assess children’s emotional reactivity in novel situations (as used in Kagan, Reznik, & Snidman, 1987; Putnam & Stifter, 2005). First, the experimenter escorted the child into a room containing several unusual objects. Mothers were in the same room but were instructed to complete questionnaires and refrain from interfering with the procedure unless there was a concern for the child’s safety. Following a period where the child was free to explore the contents of the room, an experimenter instructed the child to maneuver the objects in different ways. In the next paradigm, an unfamiliar experimenter dressed as a clown invited the child to play with different toys for 2 minutes. After the clown left the observation room, a different experimenter came to the room and presented the child with a robot who was holding an attractive toy. The robot was operated from an adjacent room via remote control and alternated between periods of inactivity and movement. The experimenter encouraged the child to approach the toy during periods in which the toy was not moving. In the final part of the paradigm, the primary experimenter portrayed the following series of behaviors and asked the child to emulate them: (1) reach behind a black curtain to retrieve a doll, (2) place a finger in glasses of water and prune juice, and (3) pick up a rubber snake and let it slide back upon the table. Coding of these temperament paradigms have been used in prior studies of at-risk parents and children with good reliability (Davies, Cicchetti, & Martin, 2012; Sturge-Apple et al., 2012).

Measures

Maternal alcohol dependence.

Maternal alcohol dependence was assessed via the Diagnostic Interview Schedule IV (DIS-IV; Robins, Cottler, Bucholz, & Compton, 1995). The DIS-IV is a comprehensive measure of adult psychopathology, including mood/depressive disorders (i.e. major depression), anxiety disorders (i.e. generalized anxiety disorder), and post-traumatic stress disorders. Furthermore, this assessment features a rich array of varying levels of substance use and misuse, including alcohol dependence. This semi-structured interview is specifically designed for use by non-clinical interviewers and researchers to capture symptoms and impairments characteristic of alcohol use disorders as delineated in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). This study will utilize the 7-item subscale for the most problematic level of use for alcohol: alcohol dependence, which can be summed and scored to create an index of alcohol dependency. Responses to each of the items are recorded in a “yes/no” format. The items included in the subscale are: (1) “alcohol tolerance”, (2) “alcohol withdrawal”, (3) “alcohol is often taken in larger amounts or over longer period than intended”, (4) “persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use”, (5) “great deal of time spent in activities to obtain, use, or recover from alcohol”; (6) “important activities are given up or reduced because of alcohol”; and (7) “alcohol use is continued despite persistent physical or psychological problem that is caused or exacerbated by alcohol”. Importantly, this index represents a combination of current, past year, and lifetime alcohol-related impairments. This robust and comprehensive index allowed us to examine the distal and proximal effects of significant alcohol misuse on parenting behaviors while also accounting for the heterogeneity in the prevalence and trajectory of alcohol dependence and alcohol-related impairments among different ethnic groups (Caetano, Clark, & Tam, 1998; Collins & McNair, 2002; Galvin & Caetano, 2003; Lex, 1987). The DIS-IV was completed by the mother at the study’s first wave with assistance from a trained experimenter. This measure has been successfully utilized by prior studies with community samples and the overall psychometric properties have been particularly strong (Compton & Cottler, 2004).

Child “vulnerable” and “dominant” negative affect.

Video recordings of children’s behavioral expressions of emotions during the unfamiliar episodes described above were independently rated by two coders. Consistent with prior procedures (Davies et al., 2012; Sturge-Apple et al., 2012), coders rated indices of ‘dominant’ and ‘vulnerable’ temperamental traits along five-point rating scales ranging from (0) ‘no’ to (4) ‘multiple, intense, and prolonged indications’. The Dominant Negative Affect subscale is indicated by aggressive and assertive behavioral responses to novel situations, high levels of frustration, anger, and hostility. The Vulnerable Negative Affect scale is indicated by distress, sadness crying, fear in novel situations, and emotional inhibition, assessed as the ability and tendency to restrain emotional expression. The intraclass correlation coefficients of the inter-rater reliability for the two independent coders ranged from .85 to .98 across the temperament dimensions, thereby indicated good to excellent reliability (Cicchetti, 1994).

Maternal harsh caregiving.

Maternal harsh caregiving was assessed via behavioral observation in both the free-play and clean-up tasks at Wave 1 when the child was 2 years old, and at Wave 2 when the child was 3 years old. Observational ratings were conducted using the scale for Harsh Maternal Caregiving from the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS; Melby & Conger, 2001). The IFIRS coding system features a global coding paradigm that was designed to examine benign and challenging parenting contexts. The Harsh subscale measures the extent to which the parent exhibits harsh, critical, angry, rejecting, and/or disapproving behavior toward the child’s behavior, appearance, or state. The parental responses included in this coding construct are intended to capture both verbal and non-verbal expressions aimed at the child. Two independent coders will complete ratings on a nine-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all characteristic) to 9 (mainly characteristic). The IFIRS system has been utilized in prior studies examining harsh caregiving behaviors across childrearing contexts, including free-play (benign) and cleanup/compliance (challenging) contexts (Sturge-Apple et al. 2012). The intraclass correlation coefficients of the inter-rater reliability for the two independent coders ranged from .89 to .98 across the three coders across the two interaction paradigms, thereby indicating good to excellent reliability (Cicchetti, 1994).

Covariate: Maternal depression symptomatology.

An index of depression symptoms was also assessed using the DIS-IV. (Robins et al., 1995). Similar to the assessment for alcohol dependence, this study will use a 9-item index designed to capture symptoms of major depression that adhere to the diagnostic criteria for depression outlined in the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The symptoms included in this subscale are: (1) “sad, angry, or depressed”; (2) “lost interest”; (3) “appetite problems”; (4) “sleep problems”; (5) “slow/restless”; (6) “tired or lack of energy”; (7) “feeling worthless or guilty”; (8) “trouble thinking”; and (9) “thoughts about death or suicide”. Each symptom was included if the participants answered “yes” to a question that captured that specific symptom.

Covariate: Maternal post-traumatic stress symptomatology (PTSS).

Maternal PTSS was also measured using the DIS-IV’s 4-item index of symptoms drawn from the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for PTSD. This index features the following symptoms: (1) “difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep”; (2) “irritability or outbursts of anger”; (3) “difficulty concentrating”; (4) “hypervigilance”; and (5) “exaggerated startle response”. The responses for these items were summed with higher scores indicating higher levels of PTSD symptomatology.

Results

Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations between primary study variables were examined using SPSS Version 25 (IBM Corp.). The means, standard deviations, and correlations for the primary study variables are presented in Table 1. Seventy-five mothers (37.9%) reported at least one psychosocial impairment stemming from alcohol dependence. A smaller subset of mothers (11.6%) endorsed 3 or more impairments associated with alcohol dependence. Patterns of missingness were examined using Little’s (1988) test for data Missing Completely at Random (MCAR). The null hypothesis for this test is that the data are MCAR. Results indicated that the data are MCAR, χ2 = 81.704, df = 97, p = .867. To maximize the study’s sample size and minimize the effect of missing data, Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) was selected as the estimator for our structural equation models that were carried out in AMOS Version 24 (Arbuckle, 2017).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for all primary study variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.W1 Mat. Alc. Dep. | |||||||||||||

| 2.W1 FP HP | .03 | ||||||||||||

| 3. W1 CP HP | −.03 | .64*** | |||||||||||

| 4. W1 Ch. Vuln. NA | −.18* | −.08 | −.09 | — | |||||||||

| 5. W1 Ch. Dom. NA | −.01 | .11 | .18* | .04 | — | ||||||||

| 6. W1 Maternal Dep. | .36*** | −.15* | −.19* | −.04 | −.01 | — | |||||||

| 7. W1 Maternal PTSD | .34*** | −.01 | −.09 | −.04 | −.01 | .38*** | — | ||||||

| 8. W2 FP HP | .07 | .38*** | .27** | .07 | −.03 | −.08* | .01 | — | |||||

| 9. W2 CP HP | .22** | .43*** | .44*** | −.13 | .11 | −.05 | −.05 | .49*** | — | ||||

| 10. Mom Age | −.06 | −.02 | −.05 | .03 | −.01 | .10 | .11 | −.23** | −.19* | — | |||

| 11. Total Family Income | −.06 | −.03 | −.07 | .02 | −.03 | .11 | .10 | −.22** | −.26** | .42*** | — | ||

| 12. Mat. AD x Ch. Vuln. NA | −.20** | −.01 | .07 | .04 | .09 | −.09 | −.11 | .04 | −.09 | −.01 | −.01 | — | |

| 13. Mat. AD x Ch. Dom. NA | −.05 | .07 | .07 | .09 | .09 | −.01 | .05 | .15 | .16* | −.02 | .01 | .21** | — |

| Mean | 0.82 | 2.03 | 2.75 | 1.40 | 1.07 | 3.48 | 1.83 | 1.55 | 1.98 | 31.15 | 25.67 | 0 | 0 |

| SD | 1.34 | 1.61 | 1.95 | .70 | .83 | 3.72 | 1.99 | 1.15 | 1.56 | 68.87 | 70.08 | 1 | 1 |

| n | 198 | 174 | 173 | 192 | 192 | 198 | 198 | 161 | 159 | 201 | 201 | 189 | 189 |

Note: Maternal alcohol dependence, maternal depression, maternal PTSD, child vulnerable negative affect, child dominant negative affect, and the interaction terms between maternal alcohol dependence and the two child temperament scales were centered. W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2. FP = Free Play; CP = Cleanup. Ch. = Child. Vuln. = Vulnerable. Dom. = Dominant. NA = Negative Affect. Dep. = Depression. AD = Alcohol Dependence.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

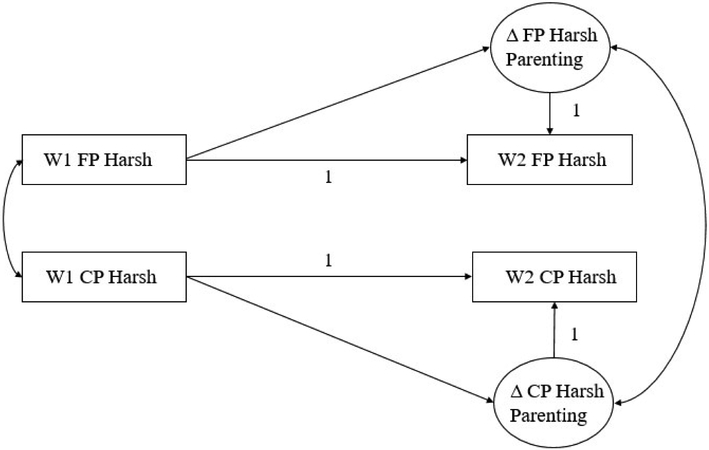

Change in maternal harsh caregiving over time was parameterized using a Latent Difference Score (LDS) approach (see Figure 1). LDS models are useful statistical models for examining change in an endogenous variable across multiple data points (McArdle & Hamagami, 2001). The LDS approach accounts for internal sources of change in a dependent variable, including the influence of initial levels on subsequent levels of that variable (King, McArdle, Saxe, Doron-LaMarca, & Orazem, 2006). Theoretically, this framework is fitting for inclusion in this study since maternal harsh caregiving is thought to naturally decrease across early childhood (Kim et al., 2010) and parametrization of LDS models account for the tendency of individuals to experience natural change over time while allowing for interindividual differences in change (King et al., 2006). Furthermore, prior research has evidenced the utility of LDS models in examining change in parenting behaviors across early childhood (i.e. Sturge-Apple, Jones, & Suor, 2017).

Figure 1.

Parameterization of latent difference score (LDS) model for baseline and change in maternal harsh caregiving in the free play and cleanup tasks. W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2. FP = Free-play; CP = Cleanup.

Analyses first examined the effect of maternal alcohol dependence on change in harsh caregiving over time and across benign and challenging parenting situations. Pairwise parameter comparisons were examined to determine whether the differential strength of predictive pathways were significantly different from one another. Next, the moderating role of child dominant negative and vulnerable temperament in the association between maternal alcohol dependence and changes in harsh parenting in benign and challenging parenting contexts was examined. To accomplish this, the two temperamental profiles were mean-centered and used to create interaction terms with maternal alcohol dependence. Lastly, maternal depression, maternal PTSD, maternal age, and total family income were entered as covariates in both SEM path models. The decision to control for depression was made for several reasons. First, depression frequently co-occurs with alcohol dependence (Boden & Fergusson, 2011), especially among women (Wilsnack, Wilsnack, & Kantor, 2013), although studies examining alcohol dependence among mothers inconsistently control for the comorbid effects of alcohol dependence and depression (Mayes & Truman, 2002). Furthermore, depression has been shown to influence parenting behaviors, especially among mothers with histories of substance use disorders (Hans, Bernstein, & Henson, 1999). Similarly, rates of depression are thought to be higher among women from ethnic minority backgrounds (Myers et al., 2002). Given that PTSD is also comorbid with alcohol dependence (Brady, Back, & Coffey, 2004), PTSD was also included as a covariate. Moreover, maternal age has been associated with harsh and punitive parenting behaviors (Lee, 2009; Trillingsgaard & Sommer, 2018), as has family income (Barajas-Gonzalez & Brooks-Gunn, 2014).

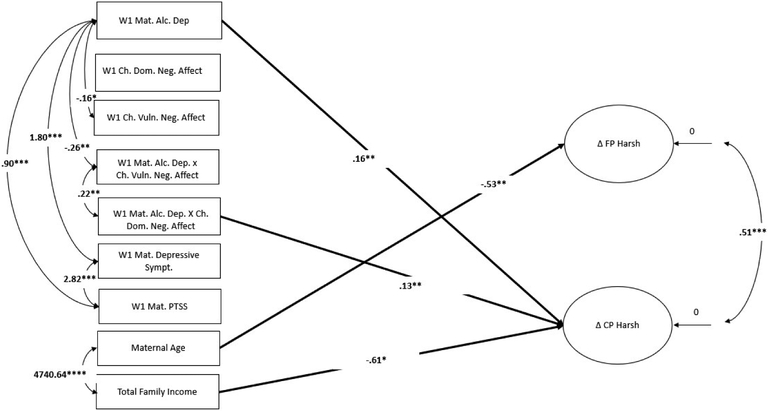

The first model examining the main effect of maternal alcohol dependence on change in harsh parenting over time indicated that maternal alcohol dependence (see Figure 2) predicted increases in harsh parenting in the cleanup task, β = . 17, SE = .09, p = .002, but not in the free-play task, β = .01, SE = .070, p = .753. Fit statistics are not provided since the model was just-identified, thereby resulting in perfect model fit and a χ2 value of 0 with 0 degrees of freedom (West, Taylor, & Wu, 2012). Pairwise parameter comparisons showed that the path from maternal alcohol dependence to change in harsh parenting in the compliance task was significantly different from the path from maternal alcohol dependence to change in harsh parenting in the free-play task, z = 2.79, p = .05. Additionally, maternal age was the only covariate that significantly predicted change in harsh parenting over time, such that younger mothers evidenced harsher parenting over time only in the free-play task, β = −.55, SE = .008, p = .007. Since our first model showed that maternal alcohol dependence predicted change in harsh caregiving in the cleanup task, and since maternal psychopathology is thought to interact with child temperament dimensions, our next model examined the moderating effect of two dimensions of child negative emotionality on associations between maternal alcohol dependence and harsh parenting.

Figure 2.

SEM path model examining the main effect of maternal alcohol dependence, maternal depression and post-traumatic stress symptomatology, maternal age, and total family income on change in harsh parenting over time in the free-play and cleanup tasks. W1 = Wave 1. Mat. = Maternal; Alc. = Alcohol; Dep = Dependence; FP = Free-Play; CP = Cleanup; PTSD = Post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

The path model examining the potential moderating effect of dominant and vulnerable negative affect on harsh parenting is depicted in Figure 3. Results show that maternal alcohol dependence predicts increases in harsh caregiving over time in the more challenging and demanding cleanup task, β = .14, SE = .09, p = .011, but not in the relatively benign free-play task, β = .03, SE = .01, p = .427. Pairwise parameter estimates indicated that this path from maternal alcohol dependence to change in harsh parenting in the compliance task was significantly different from the path estimating change in harsh parenting in the free-play task, z = 2.24, p = .025. Additionally, lower total family income predicted higher levels of harsh parenting over time in the compliance task, β = −.61, SE = .01, p = .022. Alternatively, younger mothers displayed higher levels of harshness over time in the free-play task, β = −.47, SE = .01, p = .022. Moreover, there was no significant interaction between maternal alcohol dependence and child vulnerable negative affect in predicting harsh parenting in the cleanup task, β = −.05, SE = .12, p = .321. Thus, the association between maternal alcohol dependence and increases in harsh parenting in the clean-up task was not moderated by children’s vulnerable negative affect.

Figure 3.

SEM path model examining associations between maternal alcohol dependence, child dominant negative affect, the interactions between maternal alcohol dependence and dominant and vulnerable negative affect, and change in harsh caregiving in the free play and cleanup tasks. All paths between variables were estimated but only significant paths are depicted in this figure. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Importantly, child dominant negative affect moderated the association between maternal alcohol dependence and harsh parenting in the cleanup task, β = . 13, SE = . 10, p = .010. Simple slope analyses were subsequently conducted to determine the nature and locus of the moderating effect of child dominant negative affect (see Figure 4). Results showed that the simple slope for mothers of children displaying higher levels of dominant negative affect was significantly different from zero (β = 0.49, t = 3.96, p < .001) whereas the simple slope for mothers of children with lower levels of dominant negative affect was not significantly different from zero (β = .05, t = .37, p = .71). Additional analyses were conducted to determine the regions of significance (RoS) with respect to interaction between maternal alcohol dependence and children’s dominant negative affect. Regions of significance tests provide z statistics that represent the upper and lower bounds of values for maternal alcohol dependence at which the regression of harsh parenting on child dominant negative affect is statistically significant (alpha = .05). The regression of harsh parenting on child dominant negative affect is significant for all values of maternal alcohol dependence that fall outside the region [0.433 (lower threshold), 0.969 (upper threshold)]. When the results from the above analyses are collectively considered, our findings indicate that mothers with greater psychosocial impairment from alcohol dependence who also had children exhibiting high levels of dominant negative affect displayed higher levels of harsh parenting over time in the cleanup task.

Figure 4.

Plot of simple of simple slopes of the moderating effect of child dominant negative affect on associations between maternal alcohol dependence and harsh parenting in the cleanup task. The solid line represents a slope significantly different from 0. High and low values were calculated at +/− 1 standard deviation from the mean.

Discussion

Maternal substance abuse is a ubiquitous risk factor for child psychopathology. One pathway through which maternal alcohol dependence adversely affects children’s developmental trajectories is through maladaptive parenting behaviors, such as harsh caregiving. Although prior research has identified some of the parenting deficits exhibited by alcohol-abusing mothers (i.e. Miller et al., 1999), to our knowledge, no studies have examined whether these deficits persist across childrearing contexts or how they may be influenced by specific child characteristics. Findings from this study demonstrate that maternal alcohol dependence differentially predicts harsh parenting over time and across distinct parenting situations. Moreover, our results also indicate that distinct dimensions of child negative emotionality moderate the effect of maternal alcohol dependence on parenting behaviors. Importantly, maternal alcohol dependence remains a significant and robust predictor of harsh parenting over and above other parenting risk factors, such as other manifestations of maternal psychopathology, maternal age, and family income.

The present study’s findings lead us to first consider why and how alcohol dependence uniquely undermines caregiving in discipline-oriented parenting contexts. Within these parent-child interactions, parents must adopt discipline strategies that are both flexible to their child’s distinctive behavior and won’t further increase child noncompliance and misbehavior. Therefore, sensitive parenting in discipline contexts relies on cognitive flexibility and adaptive cognitive-emotional processes (Crandall, Deater-Deckard, & Riley, 2015; Sturge-Apple et al., 2017). Specifically, disruptions in these processes can facilitate or promote harsh, coercive parenting responses, particularly at times when parenting demands are heightened, as is the case in discipline contexts. Importantly, alcohol dependence has a distinct adverse effect on many of the higher order cognitive-affective processes underlying parental sensitivity (Porreca et al., 2018; Verdejo-Garcia, Bechara, Recknor, & Perez-Garcia, 2006). Encompassed within these processes are inhibitory control, working memory, planning, and set-shifting. Research has demonstrated that deficits in these executive functions may facilitate maternal harshness, for example since prior research has demonstrated that mothers with poorer working memory are more likely to engage in harsh caregiving practices in reactions to their children’s oppositional behavior (Deater-Deckard, Sewell, Petrill, & Thompson, 2010). Therefore, reactive harshness may result from deficits in maternal working memory. In short, alcohol related impairments in maternal executive functioning may constitute one pathway through which maternal alcohol dependence may undermine adaptive parenting and aid in the development of harsh parenting behaviors.

Breakdowns in emotion regulation processes may serve as an additional avenue through which maternal alcohol dependence may lead to harsh caregiving in parent-child discipline situations. Specifically, alcohol dependence has been linked with emotion dysregulation, or the inability to adaptively and effectively regulate intense negative emotions and emotional experiences (Dvorak et al., 2014; Petit et al., 2015). Indicatively, Jakubcyzk and colleagues (2018) found that alcohol-dependent individuals had poorer emotion regulation compared to healthy controls. Particularly in demanding and emotionally challenging parenting contexts, mothers may be more likely to experience intense negative emotions, such as frustration and hostility in the presence of child noncompliance and misbehavior (Deater-Deckard, Wang, Chen, & Bell, 2012). Thus, to utilize adaptive discipline responses, parents must regulate feelings of hostility to avoid reacting harshly to their child’s behavior. Moreover, alcohol-dependent parents reported experiencing higher levels of hostility and distress when in the presence of oppositional child behavior (Pelham et al. 1997). Thus, if alcohol dependent mothers struggle to regulate their emotional distress, that dysregulation may give rise to harsh, reactive discipline practices. Although no research has comprehensively compared these processes in mothers with and without alcohol-related impairments, it may be that deficits in emotion regulation and behavioral inhibition provide further explanation for why and how maternal alcohol dependence undermines caregiving in distinct parenting contexts.

Findings regarding specificity in model pathways were also clarified by examining children’s temperamental negative emotionality. Although elements of child negative emotionality have been examined as a moderator of the relation between maternal personality characteristics and parenting (i.e. Clark et al., 2000), to our knowledge, no studies have examined whether and how distinct dimensions of child negative emotionality moderate parenting in the context of maternal psychopathology. The present study demonstrated that child dominant negative emotionality may moderate associations between maternal alcohol dependence and harsh parenting during demanding childrearing contexts. In particular, mothers who are experiencing substance use disorders may be at a heightened risk for harsh parenting when children display high levels of frustration, anger, and aggressive temperamental traits. In contrast, process pathways were not influenced by children’s displays of vulnerable emotionality. Taken together, our findings suggest that examining the moderating effect of children’s negative emotionality, and in particular increased specificity in conceptualizations of child temperament, may have important implications for parenting process models.

Maternal distress intolerance may provide one potential explanatory conceptualization regarding the moderating effect of children’s dominant negative emotionality. Traditionally, distress tolerance has referenced the ways in which an individual processes and experiences their own aversive emotional states (Simons & Gaher, 2005), but it could also encompass the way individuals perceive and process broader emotional contexts and emotional interactions. Importantly, an inability to withstand negative emotions, or distress intolerance, may increase a person’s risk to engage in maladaptive behaviors in response to stressors encountered during challenging emotional contexts (Zvolensky, Vujanovic, Bernstein, & Leyro, 2010), such as parent-child discipline situations. Within these parenting situations, parents may be prone to experience hostility and other negative emotions in the presence of child noncompliance and/or intense emotional expressions. Alternatively, parents who are predisposed to difficulties in distress tolerance may be more likely to perceive children’s dominant negative emotionality (i.e. frustration and aggression) as more intense, uncomfortable, and overwhelming. As a result of their discomfort experiencing negative emotional states, the association between maternal alcohol dependence and harsh caregiving may be particularly pronounced for mothers with lower distress tolerance who may have a strong desire to quickly remove intense affective experiences (McHugh, Reynolds, Leyro, & Otto, 2013). To borrow from diathesis-stress frameworks (i.e. Belsky & Pluess, 2009), low distress tolerance may serve as a pre-dispositional vulnerability (a diathesis) that interacts with external stressors (i.e. challenging child characteristics) to predict harsh parenting behaviors. Interestingly, no studies to date have examined how personal characteristics such as distress tolerance may operate as a diathesis factor with respect to parenting and children’s temperament, and this may be one interesting potential avenue for future research.

To understand the moderating role of children’s dominant negative affect, it is also important to consider why children’s expressions of these specific negative emotions influence harsh parenting compared to more vulnerable forms of emotionality. One possible explanation could be that children’s displays of temperamental aggression may elicit harsh, coercive parenting behaviors (Kiff, Lengua, & Zalewski, 2011; Paulussen-Hoogeboom, Stams, Hermanns & Peetsma, 2007). Specifically, research has demonstrated that heightened levels of child frustration may contribute to emotional distress within parents (Fabes, Leonard, Kupanoff, & Martin, 2001; Hagan, Luecken, Modecki, Sandler, & Wolchik, 2016). Given that alcohol dependence may disrupt the cognitive-emotional processes that regulate parents’ responses to child behavior that is emotionally aversive to the parent (Deater-Deckard et al., 2010), it may be particularly difficult for alcohol dependent mothers to respond to angry, demanding children with noncoercive discipline strategies. In contrast, our findings suggested that vulnerable emotionality consisting of heightened levels of fear, sadness, and distress did not moderate model pathways. It may be that children displaying high levels of fear and emotional reticence may fly under the radar so to speak during discipline situations. Specifically, parents with substance use disorders may not be emotionally distressed when their children are displaying these emotional expressions. Therefore, they may be less likely to respond to their child with high levels of impulsive aggression. Moreover, fearful temperamental traits may be more likely to evoke protective and nurturing maternal responses (i.e. Buss & Kiel, 2011), thus, mothers with substance use disorders may react to this domain of child negative emotionality with non-coercive caregiving behaviors.

Interestingly, maternal depressive and posttraumatic stress symptoms were not predictive of maternal harshness in either parenting context, even though other studies on parental substance abuse (i.e. Hans et al., 1999) highlight the major influence these disorders can have on caregiving. Specifically, mood disorders such as depression not only commonly co-occur with substance use disorders (Boden & Fergusson, 2011), but rates of depression may also be higher among ethnic minority women (Brown, Abe-Kim, & Barrio, 2003; Myers et al., 2002). This elevated risk for depression may stem from high rates of perceived institutional racism (Chou, Asnaani, & Hofmann, 2012) and gender discrimination (Landrine, Klonoff, Gibbs, Manning, & Lund, 1995) often endorsed by ethnic minority women. To compound this complex association between ethnicity and depression, minority women from lower-income urban communities may be more likely to suffer from severe mood disorders given the lack of access and ability to participate in psychiatric treatment programs (Miranda, Azocar, Organista, Dwyer, & Areane, 2003). Moreover, maternal psychopathology has been linked with parenting deficits and more severe forms of child maltreatment (Stith et al., 2009). Therefore, it is interesting that depressive symptomatology was not predictive of parenting deficits within our sample of high-risk, low-income, ethnic minority mothers. We assume that the underlying reason why depressive symptoms were not predictive may be because of the wording of the questions on the major depressive index that seek to capture the more severe indicators of depression. Even though the DIS-IV has been used in other ethnic minority-majority samples and been shown to be reliable, perhaps true rates of depression within our sample subclinical, and therefore were not adequately captured with the major depression index on the DIS-IV. Future studies may yield different findings for depressive symptoms when using a non-clinically based assessment with a community sample.

It was also interesting that maternal posttraumatic stress symptoms did not predict harsh caregiving, especially since PTSD and substance abuse can often co-occur among ethnic minority women (Davis, Mill, & Roper, 1997). Specifically, minority women may be at heightened risk for PTSD considering many of the traumatic events they experience (i.e. high rates of childhood maltreatment and greater exposure to assaultive violence) have been linked with PTSD in adulthood (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000; Roberts, Gilman, Breslau, Breslau, & Koenen, 2011). The risk of developing PTSD may be further exacerbated among those residing in low-income urban areas in which these traumatic experiences may be more likely to occur (i.e. Gill, Page, Sharps, & Campbell, 2008). Consequently, ethnic minority women are notably likely to experience complex trauma, typically defined as repeated exposure to multiple types of traumatic experiences (Cloitre et al., 2009), yet as a group, minority women remain underdiagnosed with PTSD relative to their Caucasian peers (Ford, 2008). This may be because many PTSD diagnostic instruments focus on an individual’s exposure to one general traumatic event rather than consistent exposure to multiple traumatic experiences that may accumulate throughout the lifespan (Cloitre et al., 2009). Therefore, measures such as the DIS-IV may feature items that inadequately capture the dynamic symptomatology associated with complex trauma, such as dissociation (Briere & Hedges, 2010; Courtois, 2008; Van der Hart, Nijenhuis, & Steele, 2005; Wilson & Keane, 2004). This inability to capture complex trauma symptoms constitutes one potential reason why maternal posttraumatic stress symptoms did not predict harsh parenting in our study. Importantly, complex trauma can undermine caregiving and healthy parent-child relationships (Banyard, Williams, & Siegel, 2003; Cohen, Hien, & Batchelder, 2008; Levendosky & Graham-Bermann, 2001; Muzik et al., 2017); however, studies of maternal substance abuse have yet to fully consider complex trauma as a contributing risk factor for maladaptive parenting. Given increasing ethnic diversity within families and the influential role of trauma exposure in ethnic minority mental health, subsequent research should strive to include comprehensive, culturally-informed PTSD assessments that directly address complex stress symptomatology. Moreover, while our findings indicated that maternal alcohol dependence uniquely undermined caregiving over and above the influence of depressive and PTSD symptoms, this may not be the case for parents and families from other cultural or sociodemographic backgrounds (i.e. immigrant families). Thus, further investigation is needed to better understand how the comorbid presentations of substance dependence and other psychopathologies may contribute to the development and maintenance of maladaptive parenting behaviors among ethnically diverse parent-child dyads.

It is also possible that parenting stress may have contributed to harsher caregiving in the cleanup task. Parenting stress is an important predictor of caregiving in general (Deater-Deckard, 1998); however, challenging parent-child situations likely elevate the amount of stress that mothers experience. Moreover, increased parenting stress has been shown to adversely influence the discipline behaviors ethnic minority and low-income mothers employ to obtain child compliance (Pinderhughes, Dodge, Bates, Petit & Zelli, 2000). While all mothers may be highly stressed in discipline contexts, alcohol-dependent mothers may be at a heightened risk to engage in harsh behaviors during stressful parenting situations. For one, prolonged chemical dependence often results in dysregulation of the neural substrates (i.e. the amygdala) that govern stress regulation and stress reactivity (Koob, 2009). Therefore, when these mothers experience high levels of parenting stress, they may respond with maladaptive parenting behaviors as a way of reducing stress. Additionally, child characteristics such as high levels of dominant negative affect may also activate these dysfunctional stress response systems. Prior research has demonstrated that parents may be more distressed when parenting a difficult or noncompliant child, which can lead parents to adopt maladaptive discipline practices (Chamberlain & Patterson, 1995; Crnic & Acevedo, 1995). Thus, parenting stress from the childrearing context in tandem with challenging child behaviors may prove particularly debilitating for alcohol-dependent mothers. It is important for future research to further unpack the role parenting stress may play on maternal caregiving since parenting stress may also facilitate the maintenance of substance dependence (Rutherford & Mayes, 2019). Indeed, Pelham and colleagues (1997) found that parents consumed more alcohol when stressed after interacting with noncompliant and difficult children. This and other research (i.e. Pelham Jr. & Lang, 1999) support the notion that parenting stress may contribute to stress-induced drinking, thereby sustaining a cycle in which chemically-dependent parents continue to abuse substances and thus, continue to engage in maladaptive parenting behaviors. In sum, future research should further examine parenting stress as a mechanism underlying the continued association between maternal alcohol dependence and harsh caregiving across specific childrearing contexts.

We believe this study’s results have notable clinical implications. First, given that mothers in our study exhibited increases in harshness in the more demanding parenting context, clinicians and interventionists may be able to isolate these parenting situations as targets of interventions, and teach alcohol dependent mothers how to sensitively and non-coercively navigate these parenting contexts. Second, many parenting interventions are focused on global conceptualizations of parenting deficits, such as maternal insensitivity (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van Ijzendoorn, & Juffer, 2003); however, our findings imply that specific forms of insensitivity (i.e. maternal harshness) may be more or less likely to manifest or increase in specific parenting situations. Thus, interventionists may also be better able to tailor parenting programs to address the distinct types of maladaptive behaviors these mothers are employing, and subsequently focus on implementing strategies that may reduce or eliminate aversive parenting behaviors (i.e. stress management). Third, this study alludes to the benefits of utilizing family-oriented interventions for substance-dependent mothers. Interventionists assisting alcohol-dependent mothers of children displaying heightened dominant negative affect may now identify their heightened risk for harsh parenting in discipline contexts. Accordingly, these mothers may benefit from parenting training that promotes maternal sensitivity in the presence of child dominant affect. Lastly, parenting interventions may be more impactful for children’s developmental trajectories if received when children are in early childhood. The behaviors parents use to obtain child compliance can have far-reaching implications for children’s behavioral outcomes (Bailey, Hill, Oesterle, & Hawkins, 2009; Brenner & Fox, 1998; Stormshak, Bierman, McMahon, & Lengua, 2000). Therefore, it is important to rectify harsh parenting behaviors that may exacerbate young children’s risk for behavioral maladjustment. Moreover, parenting interventions received when children are young may cultivate sensitive caregiving practices that promote rather than hinder positive developmental trajectories.

Importantly, many substance dependence treatment protocols exclude family members, thereby making it harder for clinicians to address parent-child relationship characteristics that may exacerbate the challenges and deficits experienced by alcohol dependent mothers. Past research has indicated the effectiveness of family-based interventions in treating adult substance abuse (Rowe, 2012), and further suggests that family-based interventions may significantly reduce the negative effects of parental substance abuse on child psychopathology (Calhoun, Conner, Miller, & Messina, 2015). However, more research is needed to develop more comprehensive parenting interventions for substance-dependent, ethnic minority mothers. Thus, future research should continue to a) investigate the parenting deficits exhibited by alcohol-dependent mothers of young children, b) determine whether and how these deficits manifest and change across parenting contexts, and c) identify child characteristics that may contribute to the development and maintenance of harsh caregiving behaviors.

Although the present study builds upon the theoretical and empirical findings of prior research, there are several limitations to note. To start, the mean number of psychosocial deficits stemming from alcohol dependence was relatively low and invariant. Since alcohol dependence was assessed via participant self-report, it is possible that low rates may be attributed to socially desirable responding, with mothers underreporting or underplaying the extent of their alcohol dependence. Findings from other studies often report higher levels of alcohol dependence or alcohol-related impairments, likely because many studies utilize samples from clinical populations (Neger & Prinz, 2015). However, rates of psychosocial impairment found in our study mirror those found in prior studies that feature community samples, especially those featuring larger proportions of ethnic minority women (i.e. Klein, Sterk, & Elifson, 2016). Interestingly, although our participants endorsed relatively few impairments, harsh parenting still increased over time in the cleanup task. Thus, even minor alcohol-related impairments can operate as robust predictors of maladaptive caregiving. Additionally, levels of harsh parenting were relatively low at both timepoints. This may have occurred because parents adopted other parenting strategies – instead of parental harshness - to garner child compliance. Parents were also aware that their interactions were being recorded, thus, it is possible that parents refrained from using intense and distinctively harsh parenting behaviors, even if those behaviors commonly occur in non-laboratory contexts. Additionally, even though this study longitudinally examined associations between maternal alcohol dependence, harsh parenting, and child negative emotionality, the relations between these constructs were only studied over the course of 1 year. Thus, a longer longitudinal study would further unpack the role of alcohol dependence on trajectories of harsh parenting across parenting contexts and developmental periods.

In summary, prior research has examined the effect of maternal substance abuse on child development, with parenting as one salient pathway that influences risks for future psychopathology. Findings from this study show that the determinants of harsh caregiving among alcohol-dependent mothers may be characterized by a complex interplay between maternal and child factors, such as children’s expressions of distinct negative emotions. Future research should continue to unpack the specific parenting deficits that alcohol-dependent mothers face while also identifying the parenting contexts in which these deficits are more likely to occur. Subsequent research should also move toward more specificity in conceptualizing the factors that modulate the effect of alcohol dependence on parenting processes and child adjustment. This may be especially beneficial since the present study shows that these contextual factors may play different roles in distinct childrearing situations. Further establishing these lines of research will inform the development and dissemination of parenting interventions that directly address the needs of this at-risk parenting population and aid in reducing the impact of maternal alcohol dependence on children’s developmental outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant R01 MH071256 from the National Institute of Mental Health awarded to Patrick T. Davies and Dante Cicchetti. We are incredibly grateful to the families who participated in our study and to the project’s research staff and student collaborators who helped make this research possible.

References

- Abidin RR (1992). The determinants of parenting behavior. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology., 21, 407–412. [Google Scholar]

- Afifi TO, Mota N, Sareen J, & MacMillan HL (2017). The relationships between harsh physical punishment and child maltreatment in childhood and intimate partner violence in adulthood. BMC Public Health, 17, 493–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL (2017). IBM SPSS AMOS 24 User's Guide. Spring House, PA: Amos Development Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Hill KG, Oesterle S, & Hawkins DJ (2009). Parenting practices and problem behavior across three generations: Monitoring, harsh discipline, and drug use in the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1214–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH, & Juffer F (2003). Less is more: Meta-analysis of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 195–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Williams LM, & Siegel JA (2003). The impact of complex trauma and depression on parenting: An exploration of mediating risk and protective factors. Child Maltreatment, 8, 334–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barajas-Gonzalez RG, & Brooks-Gunn J (2014). Income, neighborhood stressors, and harsh parenting: Test of moderation by ethnicity, age, and gender. Journal of Family Psychology, 28, 855–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeghly M, & Cicchetti D (1994). Child maltreatment, attachment, and the self system: Emergence of an internal state lexicon in toddlers at high social risk. Development and Psychopathology, 6, 5–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55, 83–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, & Pluess M (2009). Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental stressors. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 885–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden JM, & Fergusson DM (2011). Alcohol and depression. Addiction, 106, 906–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Back SE, & Coffey SF (2004). Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 206–209. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner V, & Fox RA (1998). Parental discipline and behavior problems in young children. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 159, 251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, & Valentine JD (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, 68, 748–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, & Hedges M (2010). Trauma symptom inventory. The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Bronson M (2000). Self-regulation in early childhood: Nature and nurture. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Abe-Kim JS, & Barrio C (2003). Depression in ethnically diverse women: Implications for treatment in primary care settings. Professional Psychology Research and Practice, 34, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, & Kiel EJ (2011). Do maternal protective behaviors alleviate toddlers' fearful distress. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35, 136–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL, & Tam T (1998). Alcohol consumption among racial/ethnic minorities. Alcohol Health and Research World, 22, 233–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun S, Conner E, Miller M, & Messina N (2015). Improving the outcomes of children affected by parental substance abuse: A review of randomized controlled trials. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 6, 15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, & Johnson MC (1998). Toddler regulation of distress to frustrating events: Temperamental and maternal correlates. Infant Behavior and Development, 21, 379–395. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, & Patterson GR (1995). Discipline and child compliance in parenting In Bornstein M (Ed.), Handbook of Parenting: Vol 4. Applied and Practical Parenting (pp. 205–225). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Schwartz D, Dodge KA, & McBride-Chang C (2003). Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 598–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou T, Asnaani A, & Hofmann SG (2012). Perception of racial discrimination and psychopathology across three US ethnic minority groups. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18, 74–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6, 284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Kochanska G, & Ready R (2000). Mothers' personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 274–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Stolbach BC, Herman JL, Kolk BVD, Pynoos R, Wang J, & Petkova E (2009). A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult culmulative trauma as predictors of symptom severity. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22, 399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LR, Hien DA, & Batchelder S (2008). The impact of cumulative maternal trauma and diagnosis on parenting behavior. Child Maltreatment, 13, 27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, & McNair LD (2002). Minority women and alcohol use. Alcohol Research and Health, 26, 251–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, & Cottler LB (2004). The Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS). Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment, 2, 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Reichel M, & Rowan K (2009). Exploring the associations between maternal personality, child temperament, and parenting: A focus on emotions. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Courtois CA (2008). Complex trauma, complex reactions: Assessment and treatment. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 41, 412–425. [Google Scholar]

- Crandall A, Deater-Deckard K, & Riley AW (2015). Maternal emotion and cognitive control capacities and parenting: A conceptual framework. Developmental Review, 36, 105–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic K, & Acevedo M (1995). Everyday stresses and parenting In Bornstein MH (Ed.) Handbook of Parenting, Vol. 4. Applied and Practical Parenting (pp. 277–298). Mahwah, NJ: : Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, & Papp LM (2003). Children's responses to everyday marital conflict tactics in the home. Child Development, 74, 1918–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidov M, Knafo-Noam A, Serbin LA, & Moss E (2015). The influential child: How children affect their environment and influence their own risk and resilience. Development and Psychopathology, 27, 947–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cicchetti D, & Martin MJ (2012). Toward greater specificity in identifying associations among interparental aggression, child emotional reactivity to conflict, and child problems. Child Development, 83, 1789–1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RE, Mill JE, & Roper JM (1997). Trauma and addiction experiences of African American women. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 19, 442–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K (1998). Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5, 314–332. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Sewell MD, Petrill SA, & Thompson LA (2010). Maternal working memory and reactive negativity in parenting. Psychological Science, 21, 75–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Wang Z, Chen N, & Bell MA (2012). Maternal executive function, harsh parenting, and child conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 1084–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak RD, Sargent EM, Kilwein TM, Stevenson BL, Kuvaas NJ, & Williams TJ (2014). Alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences: Associations with emotion regulation difficulties. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40, 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]