Abstract

Background

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a major cause of hepatic diseases all over the world. This necessitates the need to discover novel anti-HCV drugs to overcome emerging drug resistance and liver complications.

Purpose

Total extract and petroleum ether fraction of the marine sponge (Amphimedon spp.) were used for silver nanoparticle (SNP) synthesis to explore their HCV NS3 helicase- and protease-inhibitory potential.

Methods

Characterization of the prepared SNPs was carried out with ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy, transmission electron microscopy, and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. The metabolomic profile of different Amphimedon fractions was assessed using liquid chromatography coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry. Fourteen known compounds were isolated and their HCV helicase and protease activities assessed using in silico modeling of their interaction with both HCV protease and helicase enzymes to reveal their anti-HCV mechanism of action. In vitro anti-HCV activity against HCV NS3 helicase and protease was then conducted to validate the computation results and compared to that of the SNPs.

Results

Transmission electron–microscopy analysis of NPs prepared from Amphimedon total extract and petroleum ether revealed particle sizes of 8.22–14.30 nm and 8.22–9.97 nm, and absorption bands at λmax of 450 and 415 nm, respectively. Metabolomic profiling revealed the richness of Amphimedon spp. with different phytochemical classes. Bioassay-guided isolation resulted in the isolation of 14 known compounds with anti-HCV activity, initially revealed by docking studies. In vitro anti–HCV NS3 helicase and protease assays of both isolated compounds and NPs further confirmed the computational results.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that Amphimedon, total extract, petroleum ether fraction, and derived NPs are promising biosources for providing anti-HCV drug candidates, with nakinadine B and 3,4-dihydro-6-hydroxymanzamine A the most potent anti-HCV agents, possessing good oral bioavailability and penetration power.

Keywords: Amphimedon, nanoparticles, marine sponge, natural products, HCV helicase, protease, molecular docking, metabolomics

Introduction

Nanomaterials have a wide range of applications, though have many problems, accompanied by material sciences such as solar energy,1 microelectronics2 and antimicrobial activities.3 Several methods have been reported for the preparation of silver nanoparticles (SNPs), including chemical-based methods,4 which are not preferred, due to the toxicity of the solvents used 5 and reducing or stabilizing agents, such as N,N-dimethylformamide,6 that may lead to several biological and environmental hazards. Accordingly, green synthesis is preferred, because it utilizes the reducing power of natural extracts, a safer source for synthesized SNP reduction and stabilization.7,8 Biosynthesized silver, gold, and platinum NPs have a wide range of pharmaceutical and medical applications, such as catalysis and as antiviral and antibacterial therapeutic agents,9 in addition to the nonmedical applications, including the manufacturing of soap, cosmetic products, toothpaste, shampoo, and detergents.10 SNP-based materials have specific dimensions, with particle sizes of 1–100 nm.5 SNPs have been used in different fields, such as food packaging and water filtration, besides their multitherapeutic applications,11 including antimicrobial activities.12

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is an infectious liver disease that exists in many different genotypes. The HCV genome encodes three structural and six nonstructural proteins, of which NS3/4A protease and helicase are considered the most effective drug targets in current endeavors to design anti-HCV drug scaffolds. HCV infects about 170 million persons worldwide and thus acts as a viral pandemic,19,20 and about 3% of the world’s population is infected by it.21 Several hepatic complications, such as steatosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, are induced by HCV infection.22 One of the major health issues in Egypt is HCV, as it infects about 14.7% of the general population.23

The HCV genome consists of a single RNA-positive strand.24 A polyprotein encoded by genomic RNA is translated by an internal ribosome, followed by cleavage through viral protease into ten mature viral proteins.25 The remaining part is cleaved by viral protease, producing six nonstructural proteins, among which is NS3 protease.26 The viral replication complex is formed due to these nonstructural proteins and their host factors.24 Helicase exhibits an important role during RNA replication by unwinding the double RNA strand.27 It has several other significant roles, such as assisting in viral replication through translation and protein processing.27

Available US Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs for HCV include nucleotide derivatives, eg, sofosbuvir, and nonnucleosides, eg, boceprevir, ledipasvir, telaprevir, and simeprevir.28,29 These drugs inhibit the viral replication cycle that results in high rates of treatment in a shorter time.29 Regardless of the available drugs offering improved viral response, some side effects have been reported during treatment with telaprevir and other protease inhibitors, such as skin rash, anemia, and gastrointestinal disorders.30–32 These challenges encourage the search for new natural HCV inhibitors that can act against nonstructural proteins, such as NS3 polymerase and helicase, to inhibit virus replication.33-35

The marine ecosystem is still considered a promising reservoir of unexplored bioactive natural products. Marine metabolites have been considered a potential reservoir for antiviral compounds targeting HCV, and have provided inspiring scaffolds for combinatorial chemistry to design novel antiviral agents with enhanced therapeutic potential and minimal side effects.38–41 Several marine sponges and their associated microbiota have been explored for anti-HCV activities.24,42 Harzianoic acids A and B have been isolated from the sponge-associated Trichoderma harzianum fungus, and showed virus-inhibitory activity via reducing HCV RNA levels.29 Discorhabdins A and C and dihydrodiscorhabdin C exhibit anti-HCV activity.43 Manoalide exhibits inhibitory activity against NS3 helicase, leading to inhibition of virus RNA-helicase activity.44 Members of the genus Amphimedon exhibit a wide range of biological activities, as it includes different classes of metabolites, in particular pyridine alkaloids45 of manzamine46 and purine types,47 as well as macrocyclic lactones/lactams,48 ceramides, cerebrosides,49 and fatty acids.50,51 In the literature, among 54 extracts from different marine organisms studied, ethyl acetate from Amphimedon spp. exhibited the highest anti-HCV activity,24 as well as halitoxins, which are a group of toxic complexes with a 3-alkyl pyridinium structure isolated from the Red Sea sponge Amphimedon chloros, Haliclona sponges, and other marine sponges. It has been reported that 4.69 μg/mL of an organic extract of Amphimedon sponge containing halitoxins exhibited inhibitory activity (up to about 60%) against the West Nile Virus NS3 protease.52 Despite continuous attempts made to discover new drug candidates53, drugs with potential anti-HCV agents have remained underexplored.13 However, the use of marine material in nanomedicine remains in the early stages of investigation and faces many challenges, due to difficulties in isolation and identification of the bioactive chemical entities.14 As an example of marine organisms, the marine alga Caulerpa racemosa has been used to synthesize SNPs with antibacterial activity against Proteus mirabilis.15 Moreover, marine sponge (Haliclona exigua) NPs exhibited activity against oral biofilm bacteria, including Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus orulis.16 Nanotechnology studies have also extended to developing novel antiviral therapeutic agents that interfere with viral attachment and entry during infection.17 NPs help in the treatment of HCV through their effect on HCV NS3.18,36,37

This inspired us to explore the anti-HCV potential of Amphimedon NPs, as this has never been explored before. The anti -HCV NS3 helicase and protease activity of total extract and petroleum ether Amphimedon fractions were first investigated, followed by liquid chromatography (LC)–high-resolution electrospray ionization (HRESI)–mass spectrometry (MS)–based metabolic profiling for dereplication purposes. A mechanistic insight for the identified antiviral compounds was provided by the in silico method using molecular docking studies. The in vitro inhibitory potential of the isolated compounds against HCV replication was then tested. Finally, physiochemical properties of the isolated compounds were assessed by Veber’s oral bioavailability rule and Lipinski’s rule of five.

Methods

Sponge Material

Amphimedon marine sponge was collected from Sharm El-Shaikh (Egypt). It was then air-dried and stored at −24°C until further analysis. Voucher specimens with registration numbers BMNH 2006.7.11.1 and SAA-66 were obtained from the Natural History Museum (London, UK) and the Pharmacognosy Department (Faculty of Pharmacy, Suez Canal University, Ismailia, Egypt), respectively.

Extraction and Isolation

Freeze-dried sponge material (6 g) was extracted with methanol–methylene chloride. The resulting crude extract was fractionated between water and petroleum ether, yielding petroleum ether fraction, followed by dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, and butanol. The remaining mother liquor was then deprived of its sugars and salts with an ion-exchange resin using acetone. The organic phase in each step was separately concentrated under a vacuum, yielding petroleum ether (1 g), dichloromethane (250 mg), ethyl acetate (250 mg), butanol (1 g), and acetone (2 g) fractions. The petroleum ether fraction was chromatographed on a silica-gel column (gradient elution of petroleum ether: EtOAc, then EtOAc), followed by methanol, which was then chromatographed on a Sephadex LH-20 (Merck, Bremen, Germany) using methanol:water as eluting solvent, and final purification on semipreparative HPLC with acetonitrile (MeCN) and water as mobile phase complemented by 0.05 percent trifluoroacetic acid with a gradient elution of 10% MeCN–H2O to 100% MeCN over 30 minutes at a flow rate of 5 mL/min to yield compounds (1–14).

Synthesis of Silver SNPs

Total extract (0.002g) and petroleum ether fraction were individually dissolved in 1 mL DMSO. This was followed by the addition of 0.4 mL of each extract to 10 mL 1mM AgNO3 at room temperature.

Characterization of Synthesized SNPs by Ultraviolet-Visible Spectrometry, Transmission Electron Microscopy, and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

SNP synthesis was detected by ultraviolet (UV)-visible spectrometry using a double-beam V630 (Jasco, Japan), Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) using an FTIR-8400S, IR Prestige 21, and IR Affinity 1 (Shimadzu, Japan), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a JEM-1010, (Jeol, USA).11

Metabolic Analysis

LCMS was carried out using a Synapt G2 HDMS quadrupole time-of-flight hybrid mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, USA). The sample (2 μL) was injected into the BEH C18 column, adjusted to 40°C, and connected to the guard column. A gradient elution of mobile phase was used, starting from no solvent A and 0.1% formic acid in water to 100% acetonitrile as solvent B. MZmine 2.12 was employed for differential investigation of MS data, followed by converting the raw data into positive and negative files in mzML format with ProteoWizard.13

Anti–HCV Helicase and Protease Assay

Assay buffer (4 µL 25 mM MOPS pH 6.5, 1.25 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM DTT, 12.5 mM Tween 20, 6 µg/mL BSA) containing 5.56 nM NS3 substrate and 13.89 nM NS3 helicase fragments was distributed into wells of a 1,536 mL plate. The compounds tested (55 µL) were dissolved in DMSO. In each well, 110 mM thioflavin S or 0.8% of DMSO and 1 mL 5 mM ATP were added. Fluorescence intensity was measured after 1 hour of incubation at 25°C on a ViewLux (PerkinElmer). The ratio between RFU values obtained at t0 (RFU_t0) and t60 (RFU_t60), named Ratio_RFU, was calculated: Ratio_RFU = RFU_t60/RFU_t0. The percentage of inhibition was calculated. The activity score was classified according to the potency, ie, the most potent extract was that possessing the highest activity scores. Activity-score ranges for active and inactive extracts were 82–100 and 0–79, respectively.

Chemicals and Reagents

NS3 helicase fragments and assay buffer were supplied by Assay Provider, and 1,536-well plates (part 789,173) by Greiner. MOPS (part BP308-100), ATP (part BP413-25), and magnesium chloride (part BP214-500) were purchased from Fisher BioReagents. Thioflavin S (part T1892) was procured from Sigma-Aldrich, and a Cy5/quencher-labeled molecular beacon (custom-synthesized) was procured from Integrated DNA Technologies.

Assays of Activity of Isolated Compounds Against HCV

HCV cells were inoculated at 26×104 cells per well in a 48-well plate 24 hours before assays (Reblikon, Mainz, Germany) were conducted. Concentrations of 1–200 µM of each tested sample were prepared and a luciferase-assay system (Promega) utilized to measure luciferase activity. The resulting luminescence was measured with a luminescence plate reader (PerkinElmer) and this alternative to the level of the HCV replicon.54

Docking Studies

Docking simulations were performed using Molecular Operating Environment (MOE 2014.0901; Chemical Computing Group, Montreal, QC, Canada) on the compounds identified in Amphimedon spp., in addition to paritaprevir and ribavirin 5ʹ-triphosphate (helicase inhibitor), for the sake of comparison to their inhibitory potential.55 We drew two-dimensional structures of the known compounds with ChemSketch, then docked into the rigid binding pocket of HCV NS3–4A protease–helicase in complex with a macrocyclic protease inhibitor (PDB 4A92), HCV NS3/NS4A protease complexed with BI 201,335 (PDB 3P82), and HCV NS3 helicase with {6-(3,5-aminophenyl)-1-[4-(propane-2-yl)benzyl]-1H-indol-3-yl} acetic acid as a bound inhibitor (PDB4WXR). The 3-D crystal structure of these three enzymes was downloaded from Protein Data Bank.55,56

Results

Anti–HCV NS3 Helicase and Protease Activities

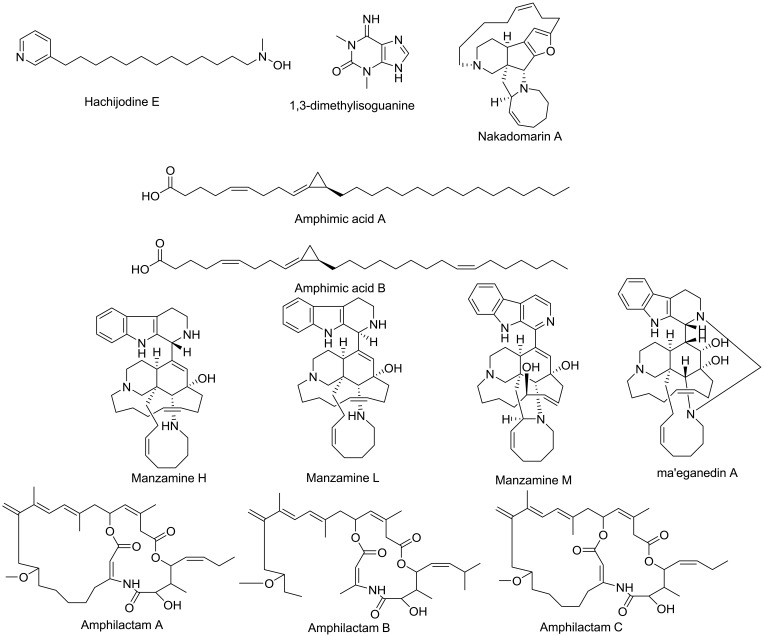

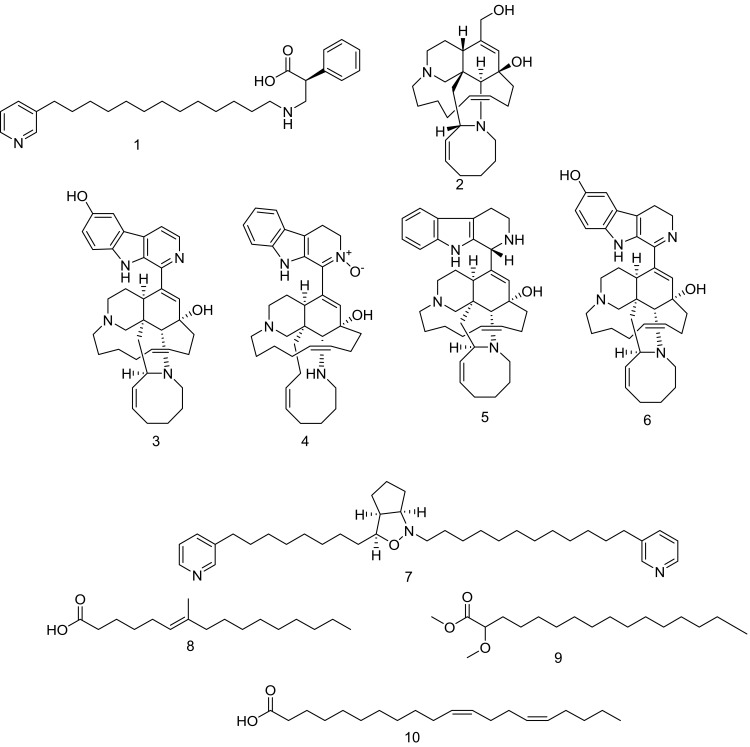

The total extract and the derived fractions of Amphimedon were tested for their HCV NS3 helicase and protease activities, and only the total extract, as well as the petroleum ether fraction, exhibited inhibitory potential against HCV NS3 helicase and protease (Table 1). This led us to use Amphimedon total extract and petroleum ether fraction in the formation of SNPs, which showed a better anti–HCV NS3 helicase and protease action (Table 2). The bioactive petroleum ether fraction was then subjected to further chromatographic separation with different chromatographic techniques to yield 14 known compounds (1–14, Figure 1), which were identified based on HRESI mass spectra in comparison to literature data.

Table 1.

In vitro Anti–NS3 Helicase and Protease Activities of Total Extract and Fractions of Amphimedon sp.

| IC50, µg/mL | ||

|---|---|---|

| NS3 helicase | NS3 protease | |

| Petroleum ether | 0.296063 | 3.875308 |

| Total extract | 2.066837 | 13.29783 |

| Butanol | 2.346521 | 35.29088 |

| Ethyl acetate | 2.782707 | 43.69913 |

| DCM | 11.09016 | 29.79358 |

Table 2.

In vitro Anti–NS3 Helicase and Protease Activities of the SNP Total Extract and Petroleum Ether Fraction of Amphimedon sp.

| IC50, µg/mL | ||

|---|---|---|

| NS3 Helicase | NS3 Protease | |

| Petroleum ether | 0.11±0.62 | 2.38±0.57 |

| Total extract | 1.52 ±1.18 | 9.76±0.58 |

| AgNO3 | 77.72 ±4.57 | 52.67±0.33 |

| Telaprevir (375 mg Tab) | — | 4.77±0.26 |

| Ribavirin | 4.66±0.29 | — |

Figure 1.

Compounds identified and dereplicated from high-resolution mass-spectra data sets of Amphimedon sp.

Metabolomic Profiling of Total Extract and Petroleum Ether Fraction of Amphimedon

The crude extract of freeze-dried Amphimedon was subjected to dereplication of secondary metabolites using LC-HR-ESIMS (Table S1 and Figure 2). Twelve compounds belonging to different chemical classes were identified. This revealed the richness of this marine sponge.

Figure 2.

Structures of isolated compounds 1–14.

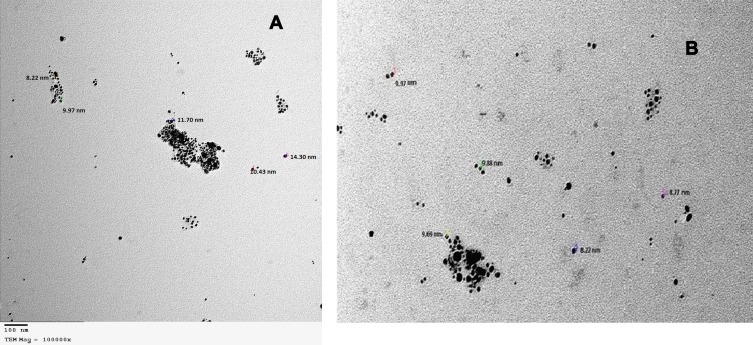

Characterization of Synthesized SNPs of Amphimedon Total Extract and Petroleum Ether Fraction

Both the total extract and petroleum ether fraction of Amphimedon, possessing the highest activity, were used in green SNP synthesis. The total extract and petroleum ether fraction of Amphimedon were treated with 1 mM AgNO3, and caused the color to change to reddish brown, indicating SNP synthesis (Figure S1). NPs of total extract and petroleum ether fraction appeared spherical, with particle sizes of 8.22–14.30 nm and 8.22–9.97 nm, respectively, on TEM analysis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

TEM for shape and size of produced SNPs of (A) total extract of Amphimedon sp. and (B) Petroleum ether fraction of Amphimedon.

Abbreviations: TEM, transmission electron microscopy; SNPs, silver NPs

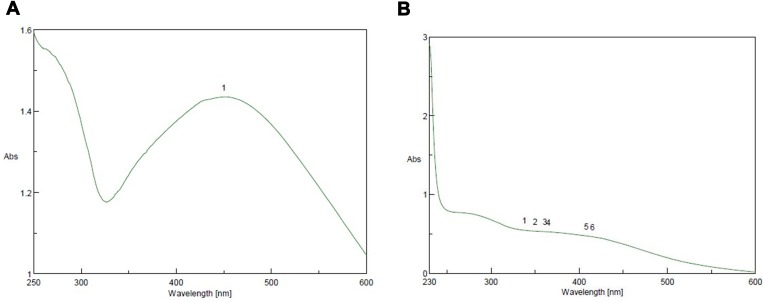

UV-Visible Characterization of Synthesized SNPs of Amphimedon Total Extract and Petroleum Ether fraction

SNP formation was controlled by UV light at a wavelength of 200–600 nm. SNPs were formed by the addition of 0.4 mL Amphimedon total extract to 10 mL AgNO3 (1 mM) and 0.6 mL petroleum ether extract of sponge extract in DMSO to of 10 mL silver (1 mM), then we used UV spectra to analyze the synthesized NPs. The total extract and petroleum ether fraction exhibited absorbance bands at 450 and 415 nm, respectively. This proved SNP synthesis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Ultraviolet-visible spectra analysis and color intensity of biosynthesized SNPs of (A) petroleum ether fraction of Amphimedon spp. and (B) total extract of Amphimedon.

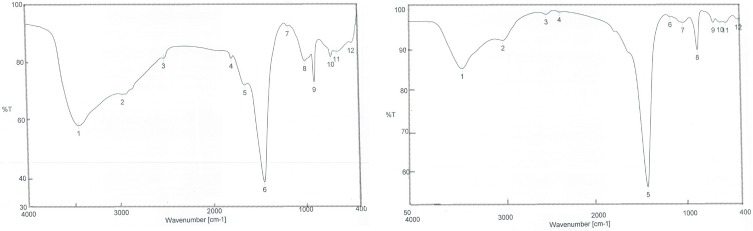

FTIR Characterization of Synthesized SNPs

FTIR was used in characterization of functional groups’ adherence to SNP surfaces. The FTIR spectrum showed peaks at 3,432.67, 3,419.17, 2,974.66, 2,930.31, 1,449.24, 876.488, and 872.631 cm−1 revealing the presence of different phytochemicals, ie, alkaloids, acids, and phenolic compounds. The peaks at 3,200–3,500 cm−1 confirmed the presence of O–H stretching of alcohols and phenolic compounds with strong hydrogen bonds, in addition to N–H group stretching. Peaks appearing at 2,800–3,000 cm−1 were characteristic of C–H and aldehydic C–H stretching. O–H stretching in carboxylic acid appeared at 2,700–3,350 cm−1. C–C stretching in an aromatic ring showed characteristic peaks in the region of 1400–1500 cm−1, which included C–H bending of alkanes at 1450–1470 cm−1. However, C–H aromatics were detected at 675–900 cm−1 (Figure 5). These groups indicated the stability of the synthesized NPs.

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra after synthesis of nanoparticles of (A) petroleum ether fraction of Amphimedon sp. and (B) total extract of Amphimedon.

Molecular Docking

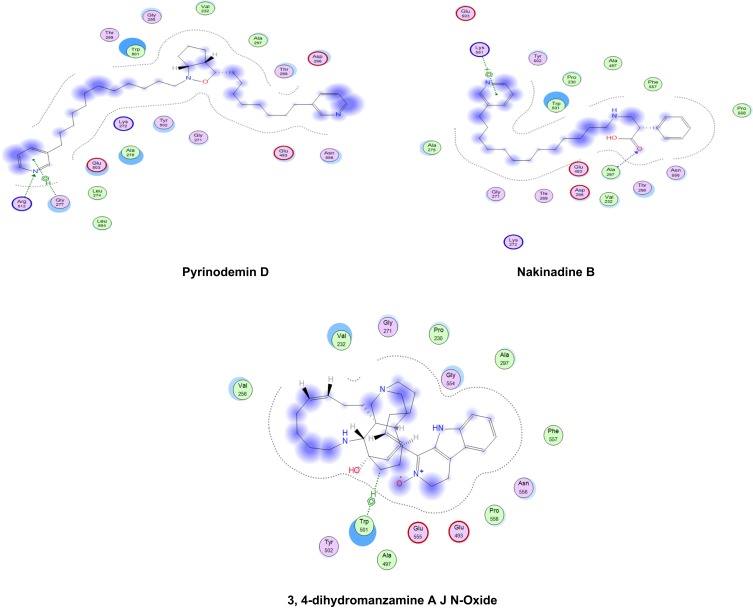

The relative inhibitory potential of the tested compounds from Amphimedon was explored against HCV NS3 protease and helicase enzymes using an in silico approach via molecular docking. The docking study showed that most of the identified compounds were able to interact with the active sites of both HCV NS3 protease and helicase domains, but with differential binding affinity, expressed as docking S-scores (Table 3 and Figure 6). The potential binding interactivity between protease and helicase domains of HCV NS3 is shown in Figures S2 and S3. Pyrinodemin D (7) and nakinadine B (1) were potential anti-HCV drug candidates, owing to their noticeably strong inhibitory activity against NS3/4A protease–helicase enzyme. In vitro investigation for the tested compounds showed that the results matched those of the in silico study: pyrinodemin D showed the highest inhibitory activity against the HCV replicon, then nakinadine B, and finally 3,4-dihydro-6-hydroxymanzamine A, while the rest of the compounds displayed weak activity.

Table 3.

Docking Scores (kcal/Mol) of the 14 Tested Compounds, Paritaprevir, and Ribavirin 5ʹ-Triphosphate Against Full-Length HCV NS3-4A Protease–Helicase (4A92), HCV NS3/NS4A Protease (3P82), and HCV NS3 Helicase (4WXR)

| S-Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4A92 | 3P82 | 4WXR | |

| Methyl 2-methoxyhexadecanoate | −5.07427 | −4.75656 | −5.51035 |

| Icrinol A | −5.34033 | −5.30877 | −5.47285 |

| 6-hydroxymanzamine A | −5.49333 | −5.37674 | −6.26323 |

| Pyrinodemin D | −6.98161 | −5.14564 | −7.64613 |

| 7-methyl-6-hexadecenoic acid | −5.09503 | −4.49901 | −5.4961 |

| Amphimedine | −5.51757 | −4.60604 | −5.1061 |

| Amphimedoside C | −5.84524 | −5.22292 | −5.84337 |

| Keramaphidin B | — | — | — |

| 20-hepacosenoic acid | −5.31298 | −5.68273 | −5.73547 |

| 3,4-dihydro-6-hydroxymanzamine A | −6.25434 | −5.9257 | −6.62751 |

| 3,4-dihydromanzamine A, J N-oxide | −6.26893 | −4.72766 | −5.56533 |

| Nakinadine B | −6.4761 | −6.17759 | −6.80996 |

| 11,15-icosadienoic acid | −5.61213 | −4.6286 | −5.78322 |

| Manzamine D | −5.62775 | −5.10746 | — |

| Paritaprevir | −5.95468 | — | |

| Ribavirin 5ʹ-triphosphate | −5.94529 | ||

Figure 6.

2-D interaction diagrams of docked compounds and ribavirin 5ʹ-triphosphate (M) with the active sites of HCV NS3 helicase (4WXR). Green arrows represent side-chain acceptor/donor; blue arrows represent backbone acceptor/donor; blue shadows represent ligand exposure.

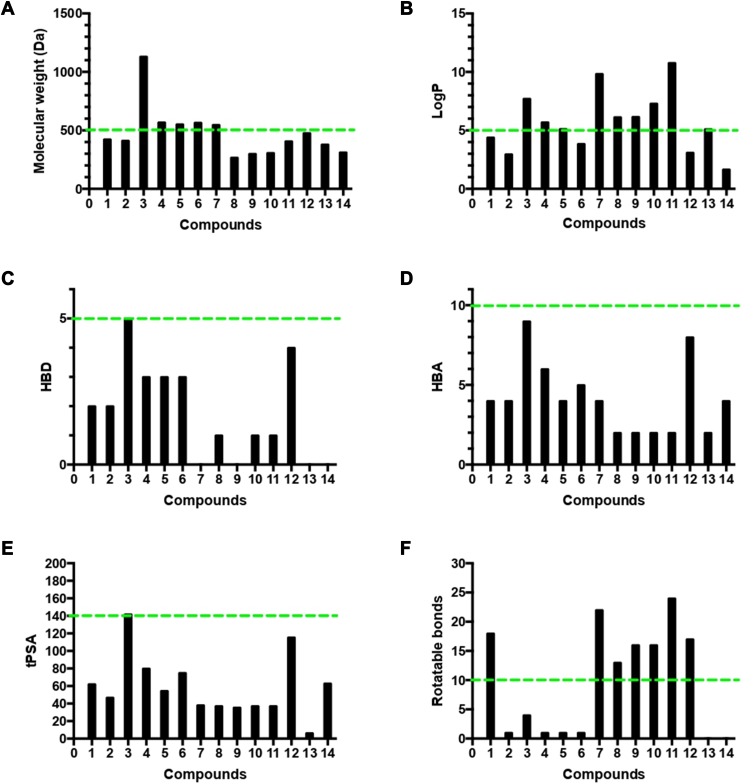

Lipinski Properties

The four Lipinski properties, in addition to two additional descriptors of topological polar surface area (tPSA) and numbers of rotation bonds of the 14 isolated compounds were analyzed (Table S2). Veber’s oral bioavailability rule was estimated, and included two additional parameter ranges (tPSA ≤140 Å, number of rotatable bonds ≤10). The isolated compounds were tested for their oral bioavailability in humans, and about 71% (ten of 14) of the isolated metabolite followed Lipinski’s rule of five with less than one violation, and the most active anti-HCV drugs perfectly obeyed the rule of five and the rule of PSA.

Discussion

Synthesis of SNPs was detected by the development of a reddish brown color at 37°C.57 The actual mechanism of SNP reduction has previously been reported.57 Both the spherical shape and size of 8.22–14.30 nm confirmed the formation of NPs, as measured by TEM. FTIR analysis revealed the presence of various phytochemical classes in the sponge with the ability to react with silver ions through their functional groups, leading to NP reduction. As previously reported, NPs may provide a successful tool in the treatment of HCV,18 given their effect against HCV NS3. The green synthesized NPs of total extract and petroleum ether fraction exhibited activity against HCV NS3 helicase (IC50 0.11±0.62 and 1.52±1.18) and protease (IC50 2.38±0.57and 9.76±0.58), while silver nitrate NPs as controls exhibited activity against HCV NS3 helicase and protease (IC50 77.72±4.57 and 52.67±0.33), respectively. This showed the power of the total extract and petroleum ether fraction synthesized NPs of Amphimedon

HR-LCMS–based metabolite profiling of sponge extracts was conducted to identify putative constituents responsible for the activity. Dereplicated identified compounds shown in Figure 1 belonged to a diverse range of phytochemical classes, such as amphimic acids (A and B)50 and alkaloids with various subclasses, eg, manzamine compounds, such as manzamine L,58 H, and M, ma’eganedin A59 and nakadomarin A,60 in addition to purine alkaloid (1,3-dimethylisoguanine)61 and pyridine alkaloids, ie, hachijodine E and62 amphilactams A, B, and C.48 Total extract and different fractions of Amphimedon were assayed in vitro against HCV NS3 helicase and protease, and the petroleum ether fraction was revealed to exhibit the most potent activity (Table 1). That is why we used this fraction in subsequent chromatographic separation with different techniques. Fourteen compounds (1–14), shown in Figure 2, were identified based on their HR-ESIMS and comparison with the literature: nakinadine B63 (1), orcinol A64 (2), 6-hydroxymanzamine A65 (3), 3,4-dihydromanzamine A, J N-oxide65 (4), manzamine D58 (5), 3,4-dihydro-6-hydroxymanzamine A66 (6), pyrinodemin D45 (7), 7-methyl-6-hexadecenoic acid67 (8), methyl 2-methoxyhexadecanoate68 (9), 11,15-icosadienoic acid67 (10), 20-hepacosenoic acid69 (11), amphimedoside C70 (12), keramaphidin B71 (13), and amphimedine72 (14).

Docking studies showed that nakinadine B (1) possessed the lowest S-score(strongest binding affinity) and ranked top of the identified compounds, followed by 3,4-dihydro-6-hydroxymanzamine A (6) and 20-hepacosenoic acid (11). Nakinadine B (1) achieved hydrogen bonding with Thr40 of the protease domain, and 3,4-dihydro-6-hydroxymanzamine A (6) had an arene–hydrogen interaction with His528 and hydrogen bonding with Cys159. 20-Hepacosenoic acid (11) showed hydrogen bonding with Arg109. Pyrinodemin D (7), nakinadine B (1), 3,4-dihydro-6-hydroxymanzamine A (6), and 6-hydroxymanzamine A (3) were noted to possess the lowest docking scores in binding with HCV NS3 helicase enzyme among the studied compounds. Gly277 and Arg512 residues of the enzyme showed arene–H and H bonding with pyrinodemin D (7), respectively. However, the two enzyme residues Lys551 and Ala297 showed arene–cation and H-bonding with pyrinodemin D (7). 6-Hydroxymanzamine A (3) showed an arene–H bond with Trp501 and an H-bond with Glu493.

To explore the combined protease and helicase–inhibition activity of the studied compounds, they were further docked against HCV NS3–4A protease–helicase (Figure S4). Pyrinodemin D (7), nakinadine B (1), 3,4-dihydromanzamine A, J N-oxide (4), and 3,4-dihydro-6-hydroxymanzamine A (6) possessed the most active inhibitors on the basis of their docking scores. Pyrinodemin D (7) had the strongest binding affinity with the helicase enzyme through H-bonding with Gly137 and Arg 123, followed by nakinadine B (1), which showed two arene–H bonds with Gln41 and Cys159 and H-bonding with Ala157. However, 3,4-dihydromanzamine A, J N-oxide (4) showed H-bonding with His57 (Figure 6). His57 and Lys136 showed arene–H bonding with 3,4-dihydro-6-hydroxymanzamine A (6). It has been reported that the existence of the protease domain in full-length NS3 can modify substrate selectivity and improve the unwinding and binding of RNA.73 Also, the helicase domain has been reported to enhance protease-domain activity when existing in full-length HCV NS3 protein,74 as exemplified by polyuracil, which has been reported to stimulate protease activity of full-length NS3 but not the isolated protease domain.75 Such activity was witnessed in our study with the compounds pyrinodemin D (7), and 3,4-dihydromanzamine A, J N-oxide (4), which had weak binding affinity with HCV NS3 protease enzymes, but were among the most active compounds inhibiting the full-length NS3–4A protease–helicase (Table 1). Additionally, it was concluded that protease improved helicase activity and vice versa,74 which might have contributed to the increased binding affinity of pyrinodemin D (7) with the full-length NS3–4A protease–helicase, despite exhibiting weak interactions with the isolated protease domain but strong inhibitory activity with the isolated helicase domain.

From this study, we can conclude that pyrinodemin D (7) and nakinadine B (1) can serve as potential anti-HCV drug candidates, owing to their observed strong inhibitory activity against the NS3–4A protease–helicase enzyme. The in silico results were substantiated by in vitro assays in which inhibitory activity against HCV replicons was recorded for pyrinodemin D, nakinadine B, and 3,4-dihydro-6-hydroxymanzamine A (IC 5.8, 15.6, and 17.2 µg/mL, respectively) the most active compounds. However, the rest of the compounds exhibited IC50 values >200 µg/mL.

Accordingly, our results highlighted pyrinodemin D, nakinadine B, and 3,4-dihydro-6-hydroxymanzamine A as the most promising anti-HCV drug leads. Since therapeutic agents must possess appropriate physicochemical properties for cell penetration and delivery to the target organ, we analyzed the four Lipinski properties and two additional descriptors — tPSA and numbers of rotation bonds for the 14 isolated compounds — to assess their oral bioavailability in humans (Table S2, Figure 7). We estimated Lipinski’s rule of five, which defines four simple physicochemical parameter ranges (MW ≤500, logP ≤5, HBD ≤5, and HBA ≤10)76 for orally active compounds and Veber’s oral bioavailability rule, which includes two additional parameter ranges (tPSA ≤140 Å, number of rotatable bonds ≤10).77 The results indicated that 71% (ten of 14) of the isolated compounds followed Lipinski’s rule of five with less than one violation: MW ≤500 Da (nine of 14, Figure 7A), logP ≤5 (five of 14, Figure 7B), HBD ≤5 (14 of 14, Figure 7C), HBA ≤10 (14 of 14, Figure 7D), tPSA ≤140 Å (13 of 14) (Figure 7E), and number of rotation bonds ≤10 (five of 14) (Figure 7F). The active anti-HCV compound nakinadine B (1) was found to perfectly obey the rule of five and the rule of tPSA, and 3,4-dihydro-6-hydroxymanzamine A (6) violated only the MW rule with 566 Da, indicating their high potential to be promising anti-HCV drug candidates with good oral bioavailability and penetration power. However, the most active compound, pyrinodemin D (7), violated both the MW and logP rules, indicating its poor oral bioavailability.

Figure 7.

Analysis of physicochemical properties for the 14 isolated compounds by (A) molecular weight, (B) log P, (C) HBD, (D) HBA, (E) tPSA, and (F) number of rotatable bonds. The green line indicates the maximum desirable value for oral bioavailability defined by Lipinski’s rule of five and Veber’s oral bioavailability rule.

Conclusion

This study presented a green synthesis of SNPs from total extract and petroleum ether fraction of Amphimedon with potent in vitro anti–HCV NS3 helicase and protease activity. A diverse phytochemical class of natural products was identified using LCMS-based metabolic investigation, followed by the identification of 14 known compounds via bioassay-guided isolation. Docking studies of the identified compounds postulated their mechanism of action, which was further evidenced by in vitro assays. Among the Amphimedon sponge phytochemicals, nakinadine B and 3,4-dihydro-6-hydroxymanzamine A were noted as promising anti-HCV drug candidates, warranting future clinical investigation.

Acknowledgment

This publication was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the University of Würzburg under the funding program Open Access Publishing. The authors are grateful to Michelle Kelly at the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), Auckland, New Zealand for taxonomic identification of the sponge samples. Thanks are also due to the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) for facilitating sample collection along the coasts of the Red Sea. We thank Maria Lesch (University of Würzburg) for her help in the laboratory.

Disclosure

Professor Dr Ronald J Quinn reports grants from the Australian Research Council during the conduct of the study. The authors declare that they have no other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Zhao T, Sun R, Yu S, et al. Size-controlled preparation of silver nanoparticles by a modified polyol method. COLLOID SURF a PHYSICOCHEM ENG ASP. 2010;366(1–3):197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2010.06.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun Y, Mayers B, Herricks T, Xia Y. Polyol synthesis of uniform silver nanowires: a plausible growth mechanism and the supporting evidence. Nano Lett. 2003;3(7):955–960. doi: 10.1021/nl034312m [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du W-L, Niu -S-S, Xu Y-L, Xu Z-R, Fan C-L. Antibacterial activity of chitosan tripolyphosphate nanoparticles loaded with various metal ions. Carbohydr. 2009;75(3):385–389. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2008.07.039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinha S, Pan I, Chanda P, Sen SK. Nanoparticles fabrication using ambient biological resources. J Appl Biosci. 2009;19:1113–1130. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amin M, Anwar F, Janjua MRSA, Iqbal MA, Rashid U. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles through reduction with solanum xanthocarpum L. berry extract: characterization, antimicrobial and urease inhibitory activities against helicobacter pylori. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(8):9923–9941. doi: 10.3390/ijms13089923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pastoriza-Santos I, Liz-Marzán LM. Formation of PVP-protected metal nanoparticles in DMF. Langmuir. 2002;18(7):2888–2894. doi: 10.1021/la015578g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou J, Zhang F, Huang J, Chang PR, Su Z, Yu J. Effects of starch nanocrystals on structure and properties of waterborne polyurethane-based composites. Carbohydr. 2011;85(4):824–831. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mondal AK, Mondal S, Samanta S, Mallick S. Synthesis of ecofriendly silver nanoparticle from plant latex used as an important taxonomic tool for phylogenetic interrelationship advances in bioresearch vol. 2. Synthesis. 2011;31:33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekhar EC, Rao K, Rao KMS, Alisha SB. A simple biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from syzygium cumini stem bark aqueous extract and their spectrochemical and antimicrobial studies. J Appl Pharm. 2018;8(01):073–079. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh M, Kalaivani R, Manikandan S, Sangeetha N, Kumaraguru AK. Facile green synthesis of variable metallic gold nanoparticle using Padina gymnospora, a brown marine macroalga. Appl Nanoscience. 2013;3(2):145–151. doi: 10.1007/s13204-012-0115-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haggag EG, Elshamy AM, Rabeh MA, et al. Antiviral potential of green synthesized silver nanoparticles of lampranthus coccineus and malephora lutea. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:6217–6229. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S214171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Nour KMA, Eftaiha A, Al-Warthan A, Ammar RA. Synthesis and applications of silver nanoparticles. Arab J Chem. 2010;3(3):135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2010.04.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shady NH, Fouad MA, Ahmed S, et al. A new antitrypanosomal alkaloid from the Red Sea marine sponge Hyrtios sp. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 2018;71(12):1036–1039. doi: 10.1038/s41429-018-0092-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srividhya S, Chellaram C. Role of marine life in nanomedicine. Ind J Innov Develop. 2012;1(S8):31–33. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kulkarni SR, Dikshit M. Indian marine pharmacology: a sneak peek into the ecosystem. Proc Indian Natl Sci Acad B. 2018;84(1):281–300. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arya G, Sharma N, Mankamna R, Nimesh S. Antimicrobial silver nanoparticles: future of nanomaterials In: Microbial Nanobionics. Springer; 2019;89–119. [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Gaied HAAA. Antiviral evaluation of secondary metabolites derived from actinomycetes conjugated to silver nanoparticles. CU Theses. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryoo S-R, Jang H, Kim K-S, et al. Functional delivery of DNAzyme with iron oxide nanoparticles for hepatitis C virus gene knockdown. Biomaterials. 2012;33(9):2754–2761. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiering N, D’Arcy A, Villard F, et al. A macrocyclic HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor interacts with protease and helicase residues in the complex with its full-length target. PNAS. 2011;108(52):21052–21056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110534108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(1):41–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chlibek R, Smetana J, Sosovickova R, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus in adult population in the Czech Republic - time for birth cohort screening. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175525–e0175525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Licata A, Minissale MG, Montalto FA, Soresi M. Is vitamin D deficiency predictor of complications development in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis? Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14(5):735–737. doi: 10.1007/s11739-019-02072-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaballah AM, Esawy MM. Comparison of 2 different antibody assay methods, Elecsys Anti-HCVII (Roche) and Vidas Anti-HCV (Biomerieux), for the detection of antibody to hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;92(2):107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2018.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujimoto Y, Salam KA, Furuta A, et al. Inhibition of both protease and helicase activities of hepatitis C virus NS3 by an ethyl acetate extract of marine sponge Amphimedon sp. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e48685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moriishi K, Matsuura Y. Exploitation of lipid components by viral and host proteins for hepatitis C virus infection. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:54. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong TT, Dat TTH, Cuc NTK, Cuong PV. Mini-review protease inhibitor (PI) and Pis from sponge-associated microorganisms. Vietnam J Sci Technol. 2018;56(4):405. doi: 10.15625/2525-2518/56/4/10911 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belon CA, Frick DN. Helicase Inhibitors as Specifically Targeted Antiviral Therapy for Hepatitis C. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen DM. A new era of hepatitis C therapy begins. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(13):1272–1274. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1100829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li B, Li L, Peng Z, et al. Harzianoic acids A and B, new natural scaffolds with inhibitory effects against hepatitis C virus. Bioorg Med Chem. 2019;27(3):560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lange CM, Sarrazin C, Zeuzem S. specifically targeted anti‐viral therapy for hepatitis C–a new era in therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(1):14–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feld JJ, Hoofnagle JH. Mechanism of action of interferon and ribavirin in treatment of hepatitis C. Nature. 2005;436(7053):967. doi: 10.1038/nature04082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kjellin M, Wesslén T, Löfblad E, Lennerstrand J, Lannergård A. The effect of the first-generation HCV-protease inhibitors boceprevir and telaprevir and the relation to baseline NS3 resistance mutations in genotype 1: experience from a small Swedish cohort. Ups J Med Sci. 2018;123(1):50–56. doi: 10.1080/03009734.2018.1441928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen C, Qiu H, Gong J, et al. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits the replication cycle of hepatitis C virus. Arch Virol. 2012;157(7):1301–1312. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1304-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalez O, Fontanes V, Raychaudhuri S, et al. The heat shock protein inhibitor Quercetin attenuates hepatitis C virus production. Hepatology. 2009;50(6):1756–1764. doi: 10.1002/hep.23232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bachmetov L, Gal‐Tanamy M, Shapira A, et al. Suppression of hepatitis C virus by the flavonoid quercetin is mediated by inhibition of NS3 protease activity. J Viral Hepatitis. 2012;19(2):e81–e88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01507.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Y, Yu S, Liu D, Proksch P, Lin W. Inhibitory effects of polyphenols toward HCV from the mangrove plant Excoecaria agallocha L. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22(2):1099–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.11.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sahuc M-E, Sahli R, Rivière C, et al. Dehydrojuncusol, a natural phenanthrene compound extracted from juncus maritimus is a new inhibitor of hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J Virol. 2019;JVI:02009–02018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sepčić K, Kauferstein S, Mebs D, Turk T. Biological activities of aqueous and organic extracts from tropical marine sponges. Mar Drugs. 2010;8(5):1550. doi: 10.3390/md8051550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shady N, El-Hossary E, Fouad M, Gulder T, Kamel M, Abdelmohsen U. Bioactive natural products of marine sponges from the genus Hyrtios. Molecules. 2017;22(5):781. doi: 10.3390/molecules22050781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abdelmohsen UR, Balasubramanian S, Oelschlaeger TA, et al. Potential of marine natural products against drug-resistant fungal, viral, and parasitic infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(2):e30–e41. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30323-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu M, El-Hossary EM, Oelschlaeger TA, Donia MS, Quinn RJ, Abdelmohsen UR. Potential of marine natural products against drug-resistant bacterial infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahmed EF, Rateb ME, Abou El-Kassem LT, Hawas UW. Anti-HCV protease of diketopiperazines produced by the Red Sea sponge-associated fungus Aspergillus versicolor. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2017;53(1):101–106. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Na M, Ding Y, Wang B, et al. Anti-infective discorhabdins from a deep-water Alaskan sponge of the genus Latrunculia. Indian J Nat Prod Resour. 2009;73(3):383–387. doi: 10.1021/np900281r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheung RCF, Wong JH, Pan WL, et al. Antifungal and antiviral products of marine organisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(8):3475–3494. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5575-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirano K, Kubota T, Tsuda M, Mikami Y, Kobayashi J. Pyrinodemins BD, potent cytotoxic bis-pyridine alkaloids from marine sponge Amphimedon sp. Chem Pharm Bull. 2000;48(7):974–977. doi: 10.1248/cpb.48.974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kubota T, Kamijyo Y, Takahashi-Nakaguchi A, Fromont J, Gonoi T, Kobayashi J. Zamamiphidin A, a new manzamine related alkaloid from an Okinawan marine sponge Amphimedon sp. Org Lett. 2013;15(3):610–612. doi: 10.1021/ol3034274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakurada T, Gill MB, Frausto S, et al. Novel N-methylated 8-oxoisoguanines from Pacific sponges with diverse neuroactivities. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;53(16):6089–6099. doi: 10.1021/jm100490m [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ovenden SP, Capon RJ, Lacey E, Gill JH, Friedel T, Wadsworth D. Amphilactams A− D: novel nematocides from Southern Australian Marine sponges of the Genus Amphimedon. JOC. 1999;64(4):1140–1144. doi: 10.1021/jo981377e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Emura C, Higuchi R, Miyamoto T, Van Soest RW. Amphimelibiosides A− F, six new ceramide dihexosides isolated from a Japanese Marine Sponge Amphimedon sp. JOC. 2005;70(8):3031–3038. doi: 10.1021/jo048635u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nemoto T, Yoshino G, Ojika M, Sakagami Y. Amphimic acids and related long-chain fatty acids as DNA topoisomerase I inhibitors from an Australian sponge, Amphimedon sp.: isolation, structure, synthesis, and biological evaluation. Tetrahedron. 1997;53(49):16699–16710. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(97)10099-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shady NH, Fouad MA, Salah Kamel M, Schirmeister T, Abdelmohsen UR. Natural product repertoire of the Genus Amphimedon. Mar Drugs. 2018;17(1):19. doi: 10.3390/md17010019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Rourke A. Bioprospecting of Red Sea Sponges for Novel Antiviral Pharmacophores. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Costa FG, BRdS N, Gonçalves RL, et al. Alkaloids as Inhibitors of malate synthase from span class=“named-content genus-species” id=“named-content-1”paracoccidioides span spp.: receptor-ligand interaction-based virtual screening and molecular docking studies, antifungal activity, and the adhesion process. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(9):5581–5594. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04711-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Montefiori DC. Evaluating neutralizing antibodies against HIV, SIV, and SHIV in luciferase reporter gene assays. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2004;64(1):12.11.11–12.11. 17. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1211s64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inc. CCG. Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), 2012.10. 1010 Sherbrooke St.west, Suite #910. Montr. QC, Canada, H3A 2R7; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nasr T, Bondock S, Eid S. Design, synthesis, antimicrobial evaluation and molecular docking studies of some new thiophene, pyrazole and pyridone derivatives bearing sulfisoxazole moiety. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;84:491–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.07.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Avilala J, Golla N. Antibacterial and antiviral properties of silver nanoparticles synthesized by marine actinomycetes. Int J Pharm Sci & Res. 2019;10(3):1223–1228. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsuda M, Inaba K, Kawasaki N, Honma K, Kobayashi J. Chiral resolution of (±)-keramaphidin B and isolation of manzamine L, a new β-carboline alkaloid from a sponge Amphimedon sp. Tetrahedron. 1996;52(7):2319–2324. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(95)01057-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsuda M, Watanabe D, Kobayashi J. Ma’eganedin A, a new manzamine alkaloid from Amphimedon sponge. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39(10):1207–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)10842-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kobayashi J, Watanabe D, Kawasaki N, Tsuda M. Nakadomarin A, a novel hexacyclic manzamine-related alkaloid from Amphimedon sponge. JOC. 1997;62(26):9236–9239. doi: 10.1021/jo9715377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jeong S-J, Inagaki M, Higuchi R, et al. 1, 3-Dimethylisoguaninium, an antiangiogenic purine analog from the sponge amphimedon paraviridis. Chem Pharm Bull. 2003;51(6):731–733. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsukamoto S, Takahashi M, Matsunaga S, Fusetani N, Van Soest RW. Hachijodines A− G: seven new cytotoxic 3-alkylpyridine alkaloids from two marine sponges of the Genera Xestospongia and Amphimedon. J Nat Prod. 2000;63(5):682–684. doi: 10.1021/np9905766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nishi T, Kubota T, Fromont J, Sasaki T, Kobayashi J. Nakinadines B–F: new pyridine alkaloids with a β-amino acid moiety from sponge Amphimedon sp. Tetrahedron. 2008;64(14):3127–3132. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.01.111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsuda M, Kawasaki N, Kobayashi J. Ircinols A and B, first antipodes of manzamine-related alkaloids from an Okinawan marine sponge. Tetrahedron. 1994;50(27):7957–7960. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)85280-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kobayashi J, Tsuda M, Kawasaki N, Sasaki T, Mikami Y. 6-Hydroxymanzamine A and 3, 4-dihydromanzamine A, new alkaloids from the Okinawan marine sponge Amphimedon Sp. J Nat Prod. 1994;57(12):1737–1740. doi: 10.1021/np50114a021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watanabe D, Tsuda M, Kobayashi J. Three new manzamine congeners from amphimedon sponge. J Nat Prod. 1998;61(5):689–692. doi: 10.1021/np970564p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carballeira NM, Restituyo J. Identification of the new 11, 15-icosadienoic acid and related acids in the sponge Amphimedon complanata. J Nat Prod. 1991;54(1):315–317. doi: 10.1021/np50073a043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carballeira NM, Colón R, Emiliano A. Identification of 2-methoxyhexadecanoic acid in Amphimedon compressa. J Nat Prod. 1998;61(5):675–676. doi: 10.1021/np970578v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carballeira NM, Negrón V, Reyes ED. Novel monounsaturated fatty acids from the sponges Amphimedon compressa and Mycale laevis. J Nat Prod. 1992;55(3):333–339. doi: 10.1021/np50081a009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Takekawa Y, Matsunaga S, van Soest RW, Fusetani N. Amphimedosides, 3-alkylpyridine glycosides from a marine sponge Amphimedon sp. J Nat Prod. 2006;69(10):1503–1505. doi: 10.1021/np060122q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kobayashi J, Tsuda M, Kawasaki N, Matsumoto K, Adachi T. Keramaphidin B, a novel pentacyclic alkaloid from a marine sponge Amphimedon sp.: a plausible biogenetic precursor of manzamine alkaloids. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35(25):4383–4386. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)73362-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schmitz FJ, Agarwal SK, Gunasekera SP, Schmidt PG, Shoolery JN. Amphimedine, new aromatic alkaloid from a pacific sponge, Amphimedon sp. carbon connectivity determination from natural abundance carbon-13-carbon-13 coupling constants. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105(14):4835–4836. doi: 10.1021/ja00352a052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Beran RK, Serebrov V, Pyle AM. The serine protease domain of hepatitis C viral NS3 activates RNA helicase activity by promoting the binding of RNA substrate. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(48):34913–34920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707165200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Beran RK, Pyle AM. Hepatitis C viral NS3-4A protease activity is enhanced by the NS3 helicase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(44):29929–29937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804065200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Morgenstern KA, Landro JA, Hsiao K, et al. Polynucleotide modulation of the protease, nucleoside triphosphatase, and helicase activities of a hepatitis C virus NS3-NS4A complex isolated from transfected COS cells. J Virol. 1997;71(5):3767–3775. doi: 10.1128/JVI.71.5.3767-3775.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lipinski CA. Lead-and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2004;1(4):337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ebejer J-P, Charlton MH, Finn PW. Are the physicochemical properties of antibacterial compounds really different from other drugs? J Cheminform. 2016;8(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s13321-016-0143-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]