Abstract

Introduction

Introducing a new arthroplasty system into clinical routine is challenging and could have an effect on early results. Since UKA are known to have failure mechanisms related to technical factors, reliable results and easy adoption are ideal. The question remains whether there are differences in objective procedure parameters in the early learning curve of different UKA systems.

Methods

two different UKA implants (Biomet Oxford[BO] followed by Conformis iuni[CI]) were introduced consecutively into clinical routine. We retrospectively analyzed the first 20 cases of each implant for one arthroplasty surgeon regarding operating time, correction of the mechanical axis, learning curve parameters, and revision rate of implants for 1.5 years postoperatively.

Results

Operating time (BO:98.3 ± 26.3min, CI:83.85 ± 21.8min (p < 0.078)), and tourniquet time differed in favor of the CI implant (BO:97.5 ± 29.5min; CI:73.5 ± 33.2 min; p < 0.017)). Mechanical alignment was restored in boths (preop:BO:mean 2.9°varus, CI:2.7°varus, postop:BOmean1.3°varus, CI:1°varus), while one BO patient and two CI patients were overcorrected. Operating time decreased from the first five implants to implants 16–20 for CI (95.2 ± 18.5min to 69 ± 21.5min, p < 0.076) and BO (130.6 ± 27.6min to 78 ± 17.3min, p < 0.009). Within 18 months of follow-up, 2 BO and 1 CI implants were revised.

Conclusion

The introduction of an UKA implant was associated with longer surgery in both implants. Procedure time seems to differ between implants, while a learning curve was observed regarding instrumentation. CI implants seem to be reliable and adaptable in a medium-volume practice. The early results of this retrospective single-surgeon study were in favor of the individualized implant. Certainly, further studies encompassing larger cohorts with various implants are needed.

Keywords: UKA, Knee, Arthroplasty, Conformis, Learning curve, Patient-specific implant

1. Introduction

Unicondylar arthroplasty is an advanced operating procedure. Besides the complex preoperative decision-making and the demanding quest for the right indication, the implantation itself is challenging.1 Especially surgeons with less experience in arthroplasty often lag behind their expected results. A high frequency (about 13 per year) of procedures is required to establish satisfactory results in a continuous manner, which is in contrast to the strict limits of indication for a unicondylar implant.2 The learning process seems to be multifactorial and depending on various individual factors, whereas the handling of the implant, the implant instrumentation, and implantation technique is established for each implant and not for each surgeon. In order to guide surgeons during the beginning of their learning curve, implant companies such as Biomet have launched obligatory courses to ensure a minimum of familiarity with this procedure prior to treating patients. Patient-specific implants, on the other hand, are also instrumented with patient-specific cutting blocks, which are fitted to the patient's anatomy. Additionally, resection is pre-planned and may be checked during the procedure to ensure the planned fit. This may be helpful to surgeons during the procedure as miscutting and misfitting may be prevented. Objective data regarding the learning curve of these implants is missing so far.

We hypothesized that there are significant differences in procedure duration, radiological outcome and early revision rate in the early learning curve of two different unicondylar knee arthroplasty systems: off-the-shelf and individualized UKA.

2. Material and methods

We retrospectively analyzed major objective procedure-associated parameters of two unikondylar implants, which were introduced into the clinical routine of a single experienced senior arthroplasty surgeon (the senior author) in one "medium-volume" orthopedic institution (a university hospital).

Regarding study design, this study focuses on the intraoperative learning curve and not on the long term outcome of two different unicondylar implants. Therefore the consecutive introduction seems to offer a proper setting, while a randomized controlled trial is not possible to undertake, as boths implants would then had to be introduced simultaneously with interfering learning-curves within.

During surgery, the surgical medial parapatellar subvastus approach was used in all cases. The preparation of the surrounding soft tissue, the cementing process, cement temperature, wound closure technique and suture of the capsule, fascia, and skin did not differ between subjects or implants. Both arthroplasty systems were implanted according to the specific operating manual. For the Oxford system, the surgeon had attended a two-day surgery skills course before the first procedure, which was mandatory on the part of the company. The Conformis implant did not require a skills course. For the first ten procedures with both arthroplasty systems, a sales representative from Biomet/Conformis was present.

Tourniquets were used for all procedures. All tourniquets were closed before skin incision and released before wound closure right after hardening of the cement and surgical coagulation/diathermy.

Operating time and tourniquet time were retrieved from the operating protocol. Mechanical alignment and correction of the mechanical axis were evaluated on total leg a.-p. radiographs within one week before surgery and approximately six weeks post-surgery.

Length of hospital stay as well as all revisions within 18 months of follow-up in this institution were retrospectively analyzed from the medical records for the first 40 cases of two different unicondylar implants (Biomet Oxford [BO] with mobile bearing and Conformis iuni [CI] with fixed bearing), which were introduced consecutively into the surgical routine of this surgeon.

Indication criteria were not changed for this procedure (unicondylar arthroplasty) within this period (January 2014 to March 2017). All indications for surgery were made by the performing surgeon himself. Indication for unicondylar arthroplasty were isolated osteoarthritis of the medial side, a stable joint with a range of motion exceeding 90° of flexion as well as full extension, isolated pain on the medial side, an intact anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), a leg deformity of less than 15° varus or 5° valgus, and absence of rheumatoid arthritis.3,4 Patients were consecutively planned for surgery, as seen in the timetable (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Surgery sequence (month/year) in chronological order and surgery time of 40 consecutive unicondylar arthroplasties.

Informed consent was obtained from all patients retrospectively for anonymous analysis and publication.

Statistics were assessed using SPSS 22.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Student's t-test for independent samples was used to reveal any significant differences between implant groups in terms of patient characteristics. Pre-to postoperative differences were calculated using an ANOVA and the Mann-Whitney-U test, respectively. For all analyses, the level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

Between January 2014 and July 2015, 20 medial unicondylar arthroplasties were performed in nine right and 11 left knees using the Oxford system. Between February 2016 and March 2017, 20 CI individually custom-made medial unicondylar implants were implanted in six right and 14 left knees by the same surgeon. Patient characteristics were comparable regarding outcome relevant measures and are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Implant |

Biomet Oxford |

Conformis iuni |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cases (n) | 20 | 20 | ||||

| side (right/left) | 9/11 | 6/14 | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.3 | ± | 5.5 | 29.7 | ± | 5.6 |

| age at operation (y) | 61.4 | ± | 8.4 | 62.9 | ± | 9.2 |

| sex (m/f) | 11/9 | 11/9 | ||||

Patient characteristics of the first 40 consecutive unicondylar implant cases, treated with either the Biomet Oxford or Conformis iuni implant by one surgeon.

Additive diagnoses/comorbidities were: hypertension in 17 patients (9 CI/8 BO), depression in four cases (2 CI/2 BO), five patients suffered from diabetes (3 CI/2 BO), three had a diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea (1 CI/2 BO), two had a history of pulmonary embolism (2 BO), one CI patient had had epileptic attacks in the past, one had a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease (BO), and one (BO) had a functioning pacemaker.

The frequency and surgery time are displayed on a timeline for each implant separately in Fig. 1.

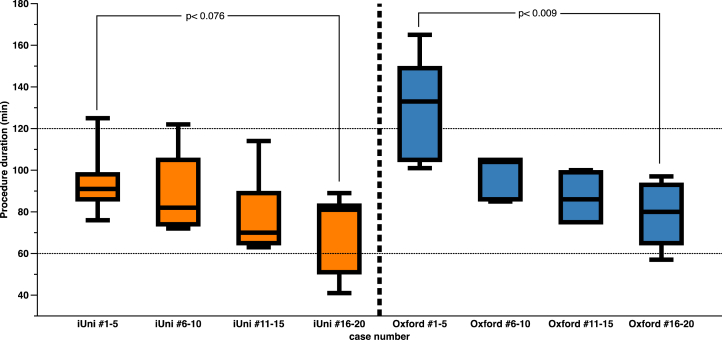

Overall average operating time (BO: 98.3 ± 26.3 min versus CI: 83.85 ± 21.8 min; p < 0.067) as well as tourniquet time differed significantly (BO: 97.5 ± 29.5 min versus CI: 73.5 ± 33.2 min; p < 0.017) and were shorter with the CI implant. Operating time decreased significantly from the first five implants (cases 1–5) to the last five implants (cases 16–20) in both groups (CI: 95.2 ± 18.5 min to 69 ± 21.5 min, p < 0.073; BO: 130.6 ± 27.6 min to 78 ± 17.3 min, p < 0.007) (Fig. 2). Tourniquet time was 73 ± 33.3 min in the CI and 97 ± 29.5 min in the BO cohort (p < 0.017).

Fig. 2.

Mean surgery times for the first 20 Conformis iuni and the first 20 Biomet Oxford cases performed by one surgeon.

The mechanical alignment was sufficiently restored (within of 3° of axis) in both groups (preop: BO: mean 2.9 °varus, CI: 2.7° varus, postop: BO mean: 1.3° varus, CI mean: 1.0° varus), while one BO patient and two CI patients were slightly overcorrected into valgus (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mechanical axis correction in the first 20 Conformis iuni and the first 20 Biomet Oxford cases. Neutral alignments (n = 1) and doubles are not shown separately.

Length of hospital stay differed between implant types; CI patients were hospitalized for 8.4 ± 1.5 days (range: 6–11) whereas BO patients spent 10.9 ± 2.9 days (range 7–17) in the hospital (p < 0.003).

Within 18 months of follow-up, two (#17 and #20) BO implants were revised, one due to aseptic loosening and one due to a persistent flexion contracture of 15° 3 months postoperatively. One CI implant (#2) was revised due to irritating bone cement on the articular side of the medial collateral ligament (MCL).

4. Discussion

This retrospective study evaluated operation-related measures of two different unicondylar implant types in order to characterize the early learning curve of these implant systems.

We found that implant-specific procedure times decreased in duration as the experience of the surgeon increased. Additionally, the recently introduced patient-specific implant system provided reliable results within the first 20 cases already, comparable to the well-established Oxford UKA system.

Commonly, the introduction of a new surgical procedure as well as a new arthroplasty system into surgical routine is challenging and bears the risk of complications. Usually, this procedure will not be performed on a high-volume basis from the start. In contrast, the perfect implant and implantation system should still be easy to learn, should guarantee good radiological and clinical results without outliers and, most of all, not compromise patient safety.

As patient selection is a significant factor for the success of this procedure, it is worth mentioning that the indication criteria regarding the implantation of a unicondylar implant were not changed during this sequence of cases. Once again, this study does not focus on functional improvement, clinical scores nor on long term outcome of different implants, but on early learning curve parameters.

Patient characteristics were not significantly different within both groups and were similar to the large study populations of Miettinen et al.5 (average of 61.4 years of age at operation) and Hamilton,6 who examined 445 medial UKA in patients aged between 37 and 95 years (mean age 66 years), with an average body mass index (BMI) of 29 kg/m2. Notably, this group implanted medial UKA in patients with leg deformities ranging 15° varus to 13° valgus.

The Oxford unicondylar knee system (Fig. 4), a mobile bearing single radius implant, is a reliable and safe procedure; it is the most commonly used UKA implant. Results of long-time users and developers state an extraordinary 20-year survival rate of 90%.7 Nowadays, on the other hand, users with less experience demonstrate far less impressive results with failure rates varying between 6%8 and 31%.9 The 1995 Swedish knee arthroplasty register additionally revealed many failures (20 out of 50) related to technical concerns.10 Especially in a lower volume setting, the results of experienced users seem unreachable, and therefore, a critical mass for annual implantation is said to be somewhere between 11 and 13 cases per year.1,2

Fig. 4.

Exemplary a.-p. radiograph of a Biomet Oxford UKA implant, cemented, mobile bearing.

Unfortunately, no long-term data on the failure rate are available for the CI implant (Fig. 5) yet, but similar bicondylar implants have shown reduced revision rates after four years in the British joint registry compared to off-the-shelf total knee arthroplasty.11 Furthermore, the newer patient-specific CI implant, which uses patient-specific instrumentation, has been shown to provide superior tibial coverage and less overhang12 while restoring the mechanical axis sufficiently and reducing outliers.13

Fig. 5.

Exemplary a.-p. radiograph of a Conformis Iuni UKA implant, cemented, fixed bearing.

Early surgical revision in unicondylar arthroplasty is mostly associated with mistaken implant positioning, cementing or surgical complications (bleeding/wound infection/inlay spin out) and independent of late implant failure. In our early results, 10% of the Biomet Oxford implants underwent revision within 1.5 years after surgery, while 5% (one case) of the unicondylar implants were revised. As stated in the result section, on BO was due to aseptic loosening and one due to a progredient extension deficit.

This is exceptionally extraordinary for the BO implant, as both revision cases (#17 and #20) happened in the last quarter of the documented sequence when the surgeon was more experienced. It therefore remains questionable as to whether a learning curve in terms of implantation quality/correctness is observed, or whether the routine speed of instrumentation has improved. Accordingly, Schroer14 experienced similar failures within a sequence of 80 BO implantations and concluded that he was unable to develop the expertise required for the Oxford implant. This author drew the apparent conclusion to abandon this implant from his surgical routine.

Our findings deviate from the literature, since two CI cases and one BO case were overcorrected into valgus, i.e. the patients received a so-called overcorrection, which is associated with premature implant failure due to overload on the lateral side of the joint.15 Koeck,13 on the other hand, found reliable restoration of the mechanical axis using the CI implant in a retrospective X-ray analysis of 32 cases.

Regarding implantation frequency, the volume of this single surgeon was about one procedure per month for BO and 1.5 procedures per month for CI, and is therefore in line with the number proposed by Baker et al.1

Within the documented period, a learning curve in terms of a reduction in operating time was noted for both implants, although procedure times for the first cases were well above the average for BO, compared to experienced users.8 Operating time is known to be a relevant factor regarding the risk for infection16 and additive trauma, due to the use of a tourniquet, which might be crucial for skeletal muscle and impair clinical outcomes.17

The average surgery time within cases 15–20 of each implant were found to be similar to the data of Zhang,8 who found 85.0 ± 15.7 min for the first 25 cases of the Oxford III system, which lowered to 64.5 ± 13.9 min for the following 25 cases.

The CI procedures were significantly shorter from the beginning, admittingly, this implantation system was introduced second. However, the requirement for patient-specific instrumentation might well be a relevant factor. Seeber et al.18 compared operating times of standard and patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) UKA procedures and concluded that using PSI technology and surgical experience were the main predictors of prolonged operating time. In contrast, 30 min of decreased surgery time was noted using patient-specific instrumentation in TKA.19 The results in this study are in line with these findings, while average surgery time differed by about 15 min in favor of the CI implant.

Finally, both procedure types showed a significant decrease in the associated operating time within the first 20 cases of each implant. The revision rate within the first 1.5 years after operation was higher than stated in the literature and mechanical alignment was restored in most cases. Failure of re-alignment might be due to the challenging procedure itself or possibly to the unexpectedly necessary precision in cutting when using individualized implants and cutting blocks.

4.1. Limitations

This study has a variety of constraints, which are partly due to the study design. It was the explicit aim of the authors to depict an early learning curve of two different implantation systems. Using the data from only 20 cases for each implant and the data of only one surgeon, as well as the short follow-up time are known weaknesses. As the focus lies on the implementation of these systems, no clinical scores were taken. Moreover, a separate analysis of the revised or overcorrected cases was not made. Therefore, transfer to other centers, fellow surgeons, or different implantation systems has to be made with caution. The introduction of new systems into practice is never an easy undertaking and should be considered wisely.

5. Conclusion

The introduction of a new implant into clinical practice was associated with a longer procedure duration and a high incidence of early revisions in both groups. Procedure time seems to be dependent on the implant, since the patient-specific implant could be implanted faster to begin with and learning curves could be observed regarding instrumentation. A learning curve regarding revision could not be seen for the Biomet Oxford implant, as both revision cases happened at the end of the series. This is in line with the revision rate of 5% in the recent literature of experienced users of this product. The Conformis iuni implant was found to provide a reliable, surgically facile implantation system alternatively in a medium-volume practice. Studies comprising a larger cohort with long-term follow-up are needed to confirm these results.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Baker P., Jameson S., Critchley R., Reed M., Gregg P., Deehan D. Center and surgeon volume influence the revision rate following unicondylar knee replacement: an analysis of 23,400 medial cemented unicondylar knee replacements. J Bone Jt Surg Am Vol. 2013;95(8):702–709. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badawy M., Fenstad A.M., Bartz-Johannessen C.A. Hospital volume and the risk of revision in Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in the Nordic countries -an observational study of 14,496 cases. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2017;18(1):388. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1750-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorbach O., Pape D., Mosser P., Kohn D., Anagnostakos K. Medial unicondylar knee replacement. Orthopä. 2014;43(10) doi: 10.1007/s00132-014-3012-9. 875-6, 8-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lobenhoffer P., Agneskirchner J.D. Umstellungsosteotomie vs. unikondyläre Prothese bei Gonarthrose. Orthopä. 2014;43(10):923–929. doi: 10.1007/s00132-014-3011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miettinen S.S., Torssonen S.K., Miettinen H.J., Soininvaara T. Mid-term results of Oxford phase 3 unicompartmental knee arthroplasties at a small-volume center. Scand J Surg. 2016;105(1):56–63. doi: 10.1177/1457496915577022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton W.G., Ammeen D., Engh C.A., Jr., Engh G.A. Learning curve with minimally invasive unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(5):735–740. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Price A.J., Svard U. A second decade lifetable survival analysis of the Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(1):174–179. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1506-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Q., Zhang Q., Guo W. The learning curve for minimally invasive Oxford phase 3 unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: cumulative summation test for learning curve (LC-CUSUM) J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;9:81. doi: 10.1186/s13018-014-0081-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zermatten P., Munzinger U. The Oxford II medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: an independent 10-year survival study. Acta Orthop Belg. 2012;78(2):203–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewold S., Goodman S., Knutson K., Robertsson O., Lidgren L. Oxford meniscal bearing knee versus the Marmor knee in unicompartmental arthroplasty for arthrosis. A Swedish multicenter survival study. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(6):722–731. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(05)80066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Implant Summary Report for the iTotal G2 XE and iTotal G2 (Bicondylar Tray) 2018. (Northgate Public Services (UK) Ltd. (NPS), 11.02.2018). [press release] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carpenter D.P., Holmberg R.R., Quartulli M.J., Barnes C.L. Tibial plateau coverage in UKA: a comparison of patient specific and off-the-shelf implants. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9):1694–1698. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koeck F.X., Beckmann J., Luring C., Rath B., Grifka J., Basad E. Evaluation of implant position and knee alignment after patient-specific unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2011;18(5):294–299. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroer W.C., Barnes C.L., Diesfeld P. The Oxford unicompartmental knee fails at a high rate in a high-volume knee practice. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(11):3533–3539. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3174-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Padgett D.E., Stern S.H., Insall J.N. Revision total knee arthroplasty for failed unicompartmental replacement. J Bone Jt Surg Am Vol. 1991;73(2):186–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Q., Goswami K., Shohat N., Aalirezaie A., Manrique J., Parvizi J. Longer operative time results in a higher rate of subsequent periprosthetic joint infection in patients undergoing primary joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(5):947–953. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayer C., Franz A., Harmsen J.F. Soft-tissue damage during total knee arthroplasty: focus on tourniquet-induced metabolic and ionic muscle impairment. J Orthop. 2017;14(3):347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2017.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seeber G.H., Kolbow K., Maus U., Kluge A., Lazovic D. Medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty using patient-specific instrumentation - accuracy of preoperative planning, time saving and cost efficiency. Zeitschrift fur Orthopadie und Unfallchirurgie. 2016;154(3):287–293. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-101559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dell'Osso G., Celli F., Bottai V. Single-use instrumentation technologies in knee arthroplasty: state of the art. Surg Technol Int. 2016;28:243–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]