On November 15, 2017, an earthquake measuring a moment magnitude of 5.5 rocked Pohang, North Gyeongsang Province in South Korea.1 Although more than a year and five months had passed since the earthquake, about 100 victims were still living in temporary shelters by April 2019. Symptomatic posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression can persist among many survivors of earthquake for even as long as 8 years after,2 and long-term evacuees (LTEs) in temporary shelters may suffer from psychological distress and numerous health problems, including infectious disease, pain, insomnia, and even premature death.3, 4, 5 However, it is often difficult to provide many evacuees with sufficient continuous mental health and psychosocial support due to limitations on human resources and a lack of stable funding. Ear acupuncture and/or ear acupressure, a treatment modality for both physical and mental health problems,6 is simple to use, effective, and has high utility. International relief organizations such as America's National Acupuncture Detoxification Association (NADA) and the organization Acupuncturists Without Borders have already been providing relief activities, using ear acupuncture at disaster sites.7, 8 This is the first report on the medical assistance using ear acupuncture for mental trauma-related symptoms of LTEs at Korean disaster sites.

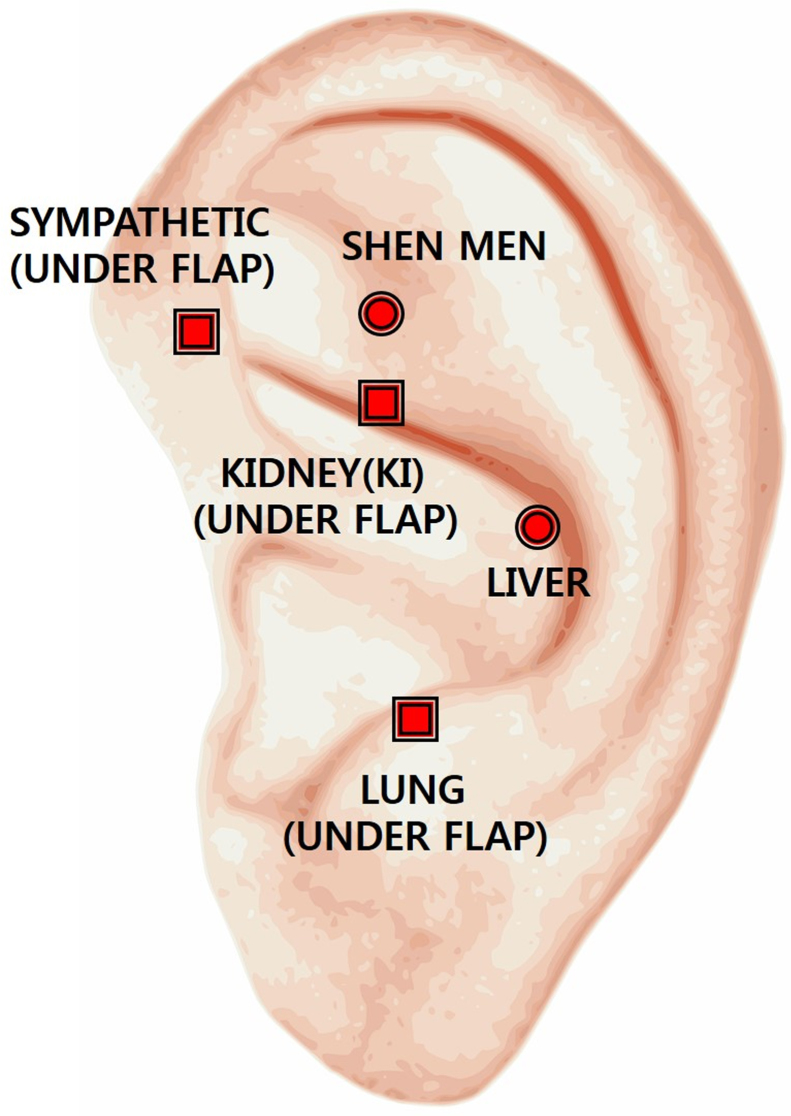

Three Korean medicine doctors provided the medical assistance with ear acupuncture twice a week for total 8 weeks, at a temporary shelter (Supplementary 1). We used the NADA protocol, a simple standardized auricular treatment protocol originally developed for use in the treatment of drug abuse using 5 auricular acupoints, Sympathetic, Shen Men, Kidney, Liver, and Lung (Supplementary 2).9 After the protocol was used as a stress reduction technique for people exposed to a severe traumatic event following the 9/11 attacks in New York,8 this protocol has been broadly used for disaster relief.10 The ear press needles were attached to the left ear every Tuesday and to the right ear every Friday, alternately. We instructed participants to press by themselves on each of the five auricular points. We used the Korean version of Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R-K) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to evaluate mental trauma-related symptoms and depression severity of the participants. Moreover, the Korean version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, the State Trait Anger Expression Inventory-Korea version, and the EuroQol 5 Dimensions were used to evaluate anger symptom, sleep quality, and quality of life. Outcome assessments were performed at baseline, 4 weeks of treatment, 8 weeks of treatment, and 4 weeks of follow-up. Sixteen consecutive LTEs with preliminary PTSD diagnosis (IES-R-K score ≥22 points) and participated in more than 12 out of the 16 treatment occasions were analyzed. Among them, 12 conducted follow-up assessment (Supplementary 3).

After 8 weeks of treatment, IES-R-K and PHQ-9 significantly decreased from 59.63 ± 13.73 to 41.13 ± 15.91 (p = 0.001) and from 15.94 ± 6.31 to 10.44 ± 5.74 (p = 0.011), respectively. After our 8-week medical assistance, the IES-R-K score continued to significantly decrease over time (from baseline to the week 4 and 8, respectively, and from the week 4 to the week 8), which was the most prominent effect. The improvements in IES-R-K and PHQ-9 were maintained until the 4-week follow-up. In addition, sleep quality, anger, and quality of life were significantly improved at 8 weeks (Table 1). No adverse events occurred during the medical assistance.

Table 1.

Scores of PHQ-9, IES-R, PSQI, STAXI, and EQ-5D-5L at baseline, week 4, and week 8

| Outcome | Baseline (n = 16) Mean ± SD |

Week 4 (n = 16) Mean ± SD |

Week 8 (n = 16) Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| IES-R | 59.66 ± 13.73 | 50.19 ± 12.68 | 41.16 ± 15.91* |

| PHQ9 | 15.94 ± 6.31 | 13.88 ± 8.59* | 1.44 ± 5.74**,+ |

| PSQI | 11.5 ± 5.28 | 11.5 ± 4.48 | 8.8 ± 5.03+ |

| STAXI-State | 25.13 ± 2.39 | 25.31 ± 1.82 | 25.31 ± 1.40 |

| STAXI-Trait | 25.00 ± 1.63 | 25.00 ± 1.63 | 24.88 ± 1.15 |

| STAXI-control | 20.27 ± 5.02 | 20.53 ± 4.31 | 17.73 ± 4.54 |

| STAXI-out | 15.27 ± 5.01 | 12.73 ± 4.44* | 13.4 ± 4.26 |

| STAXI-in | 17.87 ± 3.62 | 14.20 ± 4.62** | 11.3 ± 3.18**,+ |

| EQ-5D-moblility | 0.56 ± 1.15 | 0.81 ± 1.17 | 0.19 ± 0.66+ |

| EQ-5D-self-care | −0.62 ± 0.58 | 0.13 ± 0.50 | −0.63 ± 0.44 |

| EQ-5D-usual activities | 0.36 ± 1.02 | 1.00 ± 1.15 | 0.44 ± 1.03 |

| EQ-5D-pain/discomfort | 1.44 ± 1.36 | 1.69 ± 1.20 | 0.88 ± 1.09++ |

| EQ-5D-anxiety/depression | 1.38 ± 1.45 | 1.66 ± 1.41 | 1.19 ± 1.28 |

EEQ-5D-5L: five-level EuroQol-5 dimensions, IES-R: Impact of Event Scale-Revised, PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, STAXI: State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory.

The paired t-test for normal distributions and a Wilcoxon signed-rank test for otherwise.

p < 0.05 compared to baseline value.

p < 0.01 compared to baseline value.

p < 0.05 compared to week 4 value.

p < 0.01 compared to week 4 value.

These promising results suggest that 8 weeks of ear acupuncture could alleviate mental trauma-related symptoms in the LTEs after the 2017 Pohang earthquake. In addition, these results suggest that ear acupuncture can be used for the physical and psychological problems of survivors in large-scale disaster sites where medical resources are lacking. However, many uncontrolled confounding factors may exist in this study, due to the characteristics of the retrospective observational design. Especially, we could not control the other activities including psychoeducation at the temporary shelter, which participants had been exposed during the study period. This means that the results of this study may not reflect the actual effects of ear acupuncture. Moreover, although the IES-R-K and PHQ-9 total scores significantly decreased after ear acupuncture, the mean scores at the week 8 were above the cut-off scores for a preliminary diagnosis of PTSD and depression, which need to be managed. Therefore, further well-designed prospective randomized controlled trials with a larger sample size and a longer treatment period of more than 8 weeks are needed to investigate the effectiveness of ear acupuncture in LTEs with posttraumatic symptoms.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the staffs of the disaster psychological support center of the public health center in Pohang-si, as well as Dr. Dongeun Jin and Dr. Jihye Oh of Pohang Korean Medicine Hospital for their support.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Conceptualization: KSH and KCY. Investigation: KSH and KST. Formal analysis: KCY. Writing - original draft: KSH. Writing - review and editing: KCY and KSH.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding

This work has supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea Government (MSIT) [No. 2019R1G1A1005915]. The funding source will have no input on the interpretation or publication of the study results.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Daegu Oriental Hospital, Daegu Haany University (DHUMC-D-19015-PRO-01), and all participants signed an informed consent document.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request.

Footnotes

Supplementary 1 (a) The Heunghae Indoor Gymnasium in Pohang which was used as the temporary shelter. (b) The location of Pohang where earthquake occurred. (c) Ear acupuncture treatment in the shelter; Supplementary 2 Ear acupuncture acupoints used in this medical support; and Supplementary 3 Characteristics of the participants can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.imr.2020.100415.

Supplementary materials

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

(a) The Heunghae Indoor Gymnasium in Pohang which was used as the temporary shelter. (b) The location of Pohang where earthquake occurred. (c) Ear acupuncture treatment in the shelter.

Supplementary 2.

Ear acupuncture acupoints used in this medical support.

Supplementary 3.

Characteristics of the participants.

References

- 1.Earthquake Disaster Management Division . Ministry of the Interior and Safety; Sejong: 2018. White Paper – 2017 Pohang Earthquake. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo J., He H., Qu Z., Wang X., Liu C. Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among adult survivors 8 years after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunii Y., Suzuki Y., Shiga T., H., S., M. Severe psychological distress of evacuees in evacuation zone caused by the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident: the Fukushima Health Management Survey. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi T., Goto M., Yoshida H., Sumino H., Matsui H. Infectious diseases after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. J Exp Clin Med. 2012;4:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawano T., Nishikawa Y., Ozaki A., Leppold C., Takiguchi M., Saito H. Premature death associated with long-term evacuation among a vulnerable population after the Fukushima nuclear disaster: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e16162. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanton G. Auriculotherapy in neurology as an evidence-based medicine: a brief overview. Med Acupunct. 2018;30:130–132. doi: 10.1089/acu.2018.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yarberry M. The use of the NADA protocol for PTSD in Kenya. Deutsche Zeitsch Akupunk. 2010;53:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Acupuncture Detoxification Association . 4th ed. Wyoming; Laramie: 2011. Acupuncture detoxification specialist training resource manual. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith M.O., Khan I. An acupuncture programme for the treatment of drug-addicted persons. Bull Narc. 1988;40:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ongoing International Programs. Acupuncturists without borders web site. https://acuwithoutborders.org/international-work/ (Accessed September 3, 2019)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(a) The Heunghae Indoor Gymnasium in Pohang which was used as the temporary shelter. (b) The location of Pohang where earthquake occurred. (c) Ear acupuncture treatment in the shelter.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.