Key Points

Malat1 is suppressed during Th1 and Th2 differentiation.

Malat1 loss suppresses IL-10 and Maf expression in effector Th cells.

Malat1−/− mice mount enhanced immune responses in leishmaniasis and malaria models.

Abstract

Despite extensive mapping of long noncoding RNAs in immune cells, their function in vivo remains poorly understood. In this study, we identify over 100 long noncoding RNAs that are differentially expressed within 24 h of Th1 cell activation. Among those, we show that suppression of Malat1 is a hallmark of CD4+ T cell activation, but its complete deletion results in more potent immune responses to infection. This is because Malat1−/− Th1 and Th2 cells express lower levels of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10. In vivo, the reduced CD4+ T cell IL-10 expression in Malat1−/−mice underpins enhanced immunity and pathogen clearance in experimental visceral leishmaniasis (Leishmania donovani) but more severe disease in a model of malaria (Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi AS). Mechanistically, Malat1 regulates IL-10 through enhancing expression of Maf, a key transcriptional regulator of IL-10. Maf expression correlates with Malat1 in single Ag-specific Th cells from P. chabaudi chabaudi AS–infected mice and is downregulated in Malat1−/− Th1 and Th2 cells. The Malat1 RNA is responsible for these effects, as antisense oligonucleotide-mediated inhibition of Malat1 also suppresses Maf and IL-10 levels. Our results reveal that through promoting expression of the Maf/IL-10 axis in effector Th cells, Malat1 is a nonredundant regulator of mammalian immunity.

Introduction

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are >200-nt transcripts that lack protein-coding potential but have regulatory functions (1, 2). Mammalian genomes contain thousands of lncRNAs and demonstrate the highest frequency in lncRNA transcripts compared with any other species (1). These are mostly medium to lowly expressed transcripts, displaying poor conservation across mammals. Their modes of action vary, but they often act as scaffolds, recruiting or sequestering chromatin-modifiers or RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) to specific genomic sites (2). Despite remarkable progress in mapping lncRNAs to mammalian genomes and exploring lncRNA function at the molecular level in cellular systems, there is a profound lack of understanding of the function of lncRNAs (requirement, sufficiency, or redundancy) at the whole-organism level. For example, although CD4+ Th cells are central to pathogen-specific adaptive immunity (3), and there are hundreds of lncRNAs identified as differentially regulated during CD4+ T cell activation in humans and mice (4–6), fewer than a handful of lncRNAs have been shown to affect Th cell function. These include NeST (7), which has been shown to control its neighboring Ifng locus, and lincR-Ccr2-5′ AS (5) and linc-Maf-4 (6), which affect CD4+ T cell gene expression through long-range interactions. Therefore, the functional relevance of lncRNAs in vivo is a largely unexplored and emerging challenge in both the fields of immunology and RNA biology.

Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (Malat1) is a 7.5-kb-long long intergenic noncoding RNA (lincRNA) transcript, which is associated with cancer progression and metastasis (8). It is localized in nuclear speckles (9), which are nuclear foci enriched in factors involved in pre-mRNA splicing and transcription (10). In contrast to the vast majority of lncRNAs, Malat1 is highly conserved across mammals and highly and ubiquitously expressed (5,000–10,000 copies per cell). It has been somewhat surprising that characterization of three independent Malat1 knockout (Malat1−/−) mouse models did not reveal any homeostatic phenotypes (abnormal development, viability, fertility, or lifespan) or any patent defects in nuclear architecture (e.g., speckle formation) (11–13). In the context of CD4+ T cell function, two recent reports presented contradicting results regarding Malat1 function; Yao and colleagues (14) found that Malat1 does not affect number of CD4+ T cells and T follicular helper cells or CD8+ T cells responses to lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) in vivo and concluded that Malat1 is dispensable for CD4+ T cell function and development, whereas Masoumi and colleagues (15) reported that Malat1 is downregulated in tissues from patients with multiple sclerosis and mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and that small interfering RNA–mediated knockdown of Malat1 promoted Th1/Th17 polarization and inhibited T regulatory cell differentiation in vitro. The above demonstrate that the physiological function of Malat1 in vivo and potential role in adaptive immunity remain poorly understood.

In this study, through defining the lncRNA signature of early Th cell activation, we show that Malat1 is one of the most highly abundant transcripts in naive CD4+ T cells and it is downregulated within the first 24 h of naive CD4+ T cell activation. Suppression of Malat1 expression is sustained and observed in in vitro–differentiated Th1 and Th2 cells. Single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analyses of in vivo–derived Ag-specific Th1 cells demonstrate that Malat1 expression inversely correlates with expression of transcriptional units involved in RNA processing and translation, protein degradation, metabolism, and cellular structure, all hallmarks of Th activation. Similar correlations are seen in Th2 cells. Conversely, Malat1 expression positively correlates with expression of Maf (also known as c-Maf). Functionally, when compared with wild-type (WT) C57BL6 controls, in vitro–generated Malat1−/− Th1 and Th2 cells express lower levels of Maf and its transcriptional target IL-10. Suppression of IL-10 expression in Malat1−/− CD4+ T cells is also observed in mice infected with the protozoan parasite Leishmania donovani or with Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi AS (PcAS). Malat1−/− mice demonstrate enhanced macrophage activation and parasite clearance in the visceral leishmaniasis model, but more pronounced disease in experimental malaria, similarly to phenotypes observed in IL-10–deficient mice. Overall, our results demonstrate that Malat1 suppression is a hallmark of CD4+ T cell activation and controls IL-10 expression in Th cells. We propose that suppression of Malat1 in activated CD4+ T cells is a critical determinant of optimal immunity to chronic infection.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

Animal care and experimental procedures were regulated under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 (revised under European Directive 2010/63/EU) and were performed under U.K. Home Office License (project license number PPL 60/4377 with approval from the University of York Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body). Animal experiments conformed to Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments guidelines.

Mouse infections

Female C57BL/6 CD45.2 mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. Malat1−/− mice (complete knockouts) were obtained from the Riken Institute (12). All mice were bred in-house, maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions, and used at 6–12 wk of age. The Ethiopian strain of L. donovani (LV9) was maintained by passage in RAG-2−/− mice. Mice were infected i.v. with 30 × 106 amastigotes via the tail vein. Parasite burden was expressed parasite count per 100 host cell nuclei or as Leishman–Donovan units (the number of parasites per 1000 host cell nuclei × organ weight in milligrams).

Female C57BL/6 or Malat1−/− mice (6–12 wk old) were infected with PcAS through i.v. injection of 1 × 105 parasitized erythrocytes under reverse light cycles. Parasitemia was monitored from day 5 onwards by thin blood smears stained with Giemsa stain (infected red cells per 1000 red cells × 100). Mice were bled within the first 2 h of the dark cycle. Weights and signs of disease were monitored daily.

FACS analysis and cell sorting

For FACS analysis, spleens were first digested with 0.4 U/ml Liberase TL (Roche) and 80 U/ml DNase I type IV in HBSS (both Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min at 37°C. Enzyme activity was inhibited with 10 mM EDTA (pH 7.5) and single-cell suspensions were created with 70-μm nylon filters (BD Biosciences) in complete RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS (HyClone), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine (all Thermo Fisher Scientific). RBCs were lysed with RBC lysing buffer (Sigma-Aldrich). For live/dead discrimination, cells were washed twice in PBS, then stained with Zombie Aqua (BioLegend) before resuspension in FACS buffer (PBS containing 0.5% BSA and 0.05% azide). Fc receptors were blocked with 100 μg/ml rat IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min at 4°C before surface staining for 30 min at 4°C. Combinations of the following anti-mouse Abs were used: CD45.1 allophycocyanin (clone A20); CD45.2 BV786 (104); CD3 FITC (145-2C11); B220 FITC (RA3-6B2); TCRβ PE-Cy7 (H57-597); MHC class II (MHCII) Alexa Fluor 700 (M5/114.15.2); Ly-6G PE-Cy7 (1A8); CD11b Pacific Blue and allophycocyanin (M1/70); CD11c PerCP/Cy5.5 (N418); F4/80 FITC and Alexa Fluor 647 (BM8); CD44 FITC (IM7); CD62L PE (MEL-14); CD8α allophycocyanin (53-6.7); CD4 PE and PerCP/Cy5.5 (RM4-5); IFN-γ FITC (XMG1.2); IL-10 PE (JES5-16E3); and IL-17A PE/Cy7 (TC11-18H10.1). All Abs were from BioLegend. To measure intracellular cytokines in T cells following ex vivo stimulation, cells were first stimulated in complete RPMI 1640 for 4 h at 37°C with 500 ng/ml PMA, 1 μg/ml ionomycin, and 10 μg/ml brefeldin A (all Sigma-Aldrich). For all intracellular cytokine staining, surface stained cells were fixed and permeabilized (20 min at 4°C) using Fixation/Permeabilization Solution before washes in Perm/Wash buffer (both BD Biosciences). Cells were then stained with intracellular Abs as above except in Perm/Wash buffer. Appropriate isotype controls were included. For FACS analysis, events were acquired on an LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences) before analysis with FlowJo (FlowJo). For cell sorting of splenic lymphocytes from naive and L. donovani–infected spleens, CD4+ T cells were sorted as B220− CD3+ CD4+ CD8a−. For purification of naive and activated CD4+ T cells from uninfected mice, single-cell suspensions were prepared from pooled spleens and peripheral lymph nodes (axillary, brachial, and inguinal). CD4+ cells were enriched using CD4 microbeads and LS columns (Miltenyi Biotec) before cell sorting of naive CD4+ T cells (CD4+ CD62L+ CD44− CD11b− CD8a− MHCII−). Cell sorting was performed with a MoFlo Astrios (Beckman Coulter), and sorted cells were typically >98% positive.

In vitro activation of CD4+ T cells

Purified CD4+ T cells were stimulated with 10 μg/ml plate-bound anti-CD3ε (clone 145-2C11) and 2 μg/ml soluble anti-CD28 (37.51) in RPMI 1640 as before in flat-bottom 96-well plates (Th0 conditions). For Th1 polarization, cells were also treated with 15 ng/ml mouse rIL-12 and 5 μg/ml anti–IL-4 (11B11) or, for Th2 polarization, 30 ng/ml mouse rIL-4 and 5 μg/ml anti–IFN-γ (XMG1.2). To induce suboptimal Th1 differentiation (weakly polarizing conditions), 1% of the original stimulation concentrations of recombinant cytokine rIL-12 and anti–IL-4 were included in the cell culture medium. To induce suboptimal Th2 differentiation, 2% of the original concentrations of rIL-4 or anti–IFN-γ were included in the cell culture medium. Anti-CD3/anti-CD28–dependent activation (4 d) was followed by rest in 10 U/ml human rIL-2 (2 d). To induce Th17 differentiation, naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with 10 ug/ml plate-bound anti-CD3 (145-2c11) and 4 μg/ml soluble anti-CD28 (37.51), and 1 ng/ml of rTGF-β, 37.5 ng/ml rIL-6, 5 μg/ml anti–IFN-γ (XMG1.2), and 5 μg/ml anti–IL-4 (11B11). After 3 d of stimulation, cells were transferred to a new 96-well plate in the presence of half the concentration of recombinant cytokines and inhibiting Abs. Cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry at day 5. All Abs were from BioLegend and were low on endotoxin and azide free. Recombinant cytokines were from PeproTech. Control or Malat1-targeting antisense oligonucleotide gapmers were from QIAGEN (Hilden, Germany; LG00000002-DDA and LG00000008-DDA, respectively) and were added to naive CD4+ T cells on day 0 at a final concentration of 100 nM.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from tissue samples or purified cell populations using QIAzol and miRNeasy RNA extraction kits (QIAGEN) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Tissue samples were first dissociated in QIAzol using a TissueLyser LT with stainless steel beads (all QIAGEN). For mRNA transcripts, reverse transcriptions were carried out with Superscript III (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and random hexamer primers (Promega) and measured with Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PCR were performed using a StepOnePlus Real Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and relative transcript levels were determined using the ∆∆Ct method. The following primer sequences were used: Malat1 forward, 5′-TGCAGTGTGCCAATGTTTCG-3′; Malat1 reverse, 5′-GGCCAGCTGCAAACATTCAA-3′; Neat1 forward, 5′-CCTAGGTTCCGTGCTTCCTC-3′; Neat1 reverse, 5′-CATCCTCCACAGGCTTAC-3′; U6 forward, 5′-CGCTTCGGCAGCACATATAG-3′; and U6 reverse, 5′-TTCACGAATTTGGCTGCTAT-3′.

For all other genes commercially available, QuantiTect (QIAGEN) primer sets were used.

RNA-seq analysis

For single-cell RNA-seq analyses, Smart-seq2 single-cell RNA-seq FASTQ files were obtained from ArrayExpress (www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/), accession numbers E-MTAB-4388 (Th1) and E-MTAB-2512 (Th2). Sequencing reads were mapped to the mouse mm10 Ensembl 84 reference genome with External RNA Controls Consortium RNA spike-in sequences using star 2.5.1b and quantified with HTSeq 0.9.1. Normalization and filtering of data were performed using Seurat (version 3.0.0). Cells with expression of fewer than 200 genes and/or a mitochondrial read proportion above 5% were excluded from analysis. Genes were filtered for minimum expression in three cells. Gene correlations were determined from log-normalized expression data using cor.test function (stats package) with Spearman rho statistic to estimate a rank-based measure of association.

Bulk RNA-seq analyses were performed as previously described (16). Briefly, we compared four naive CD4+ T cells against four activated (24 h) samples. We obtained 10 million reads per sample on average (range: 4–20 million). Sequence reads were trimmed to remove adaptor sequences with Cutadapt and mapped to mouse genome GRCm38 with HISAT2, including rna-strandness FR option. Transcriptome assembly and quantification was performed using the Tuxedo pipeline (version 2.2.1). Cufflinks was used to assemble transcriptomes for each sample using the Gene transfer format annotation file for the GRCm38 mouse genome. This was followed by running Cuffmerge to merge individual sample transcriptomes into full transcriptomes. Quantification and normalization were carried out for each experiment using Cuffquant and Cuffnorm. Differential expression on gene fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) values was performed by conducting paired and independent t tests with Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate correction. Data are available at Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) accession number GSE125268 (wild-type samples only). Gene ontology and Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) analysis (http://string-db.org/) were performed where indicated. STRING settings were highest-confidence interactions only excluding text mining. Transcription factors and cofactors were extracted by comparing gene lists to the TFcheckpoint database (http://www.tfcheckpoint.org/).

Western blotting

Cells were washed twice in PBS and protein extracts prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.2), 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM PMSF, 1% protease inhibitor mixture P8340, and 1% phosphate inhibitor mixtures 2 and 3; all Sigma-Aldrich). Equal total amounts of protein were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (MilliporeSigma) using a Bio-Rad SD Semi-Dry Transfer Cell, blocked for 2 h at room temperature in 2% BSA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or 5% milk powder (Sigma-Aldrich) in TBST (150 mM NaCl, 7.7 mM Tris HCl [pH 8], and 0.1% Tween 20; all Sigma-Aldrich) before overnight probing with primary Abs at 4°C. Abs were as follows: Maf (55013-1-AP) and Stat4 (51070-2-AP) from Proteintech, Histone 3 from Cell Signaling Technology. Following extensive washing in TBST, blots were incubated with secondary Abs (goat anti-rabbit or mouse HRP; DAKO) for 1 h at room temperature, washed as before, and developed with ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent and Hyperfilm ECL (both GE Healthcare).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out as indicated with Prism 5 (GraphPad Software). Two-way comparisons used paired or unpaired t tests as indicated, and multiple comparisons used one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. Any p values <0.05 were considered significant. All p values are shown when significant or borderline.

Results

Malat1 is suppressed at the early stages of CD4+ T cell activation

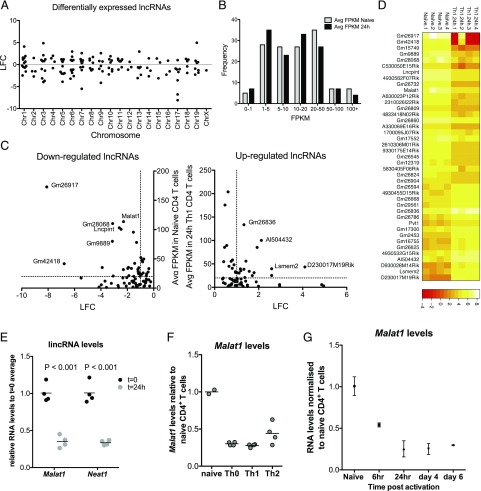

To gain insight into the role of the noncoding transcriptome in CD4+ T cell function, we began our studies by using bulk RNA-seq to determine early (24 h) changes in expression of lncRNAs under in vitro Th1-polarizing conditions. We identified 120 differentially expressed lncRNAs, the majority of which were intergenic, distributed across the genome (Fig. 1A). As expression of lncRNAs varied (Fig. 1B), we set an additional criterion in our analysis and identified 23 lncRNAs that were expressed in CD4+ T cells at FPKM > 20 and were differentially regulated (log2 fold change [LFC] > 1 or LFC < −1) between naive and 24-h-activated CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1C, 1D). We observed a significant correlation between changes in expression of the identified lncRNAs and their chromosomally adjacent genes (Supplemental Fig. 1A), which inferred the existence lncRNA-mediated in cis regulatory effects across the CD4+ T cell transcriptome, in agreement with previous studies (1).

FIGURE 1.

Identification of differentially regulated lncRNAs upon activation of naive CD4+ T cells reveals Malat1 suppression as a hallmark of Th cell activation. (A) LFC of statistically significantly differentially regulated lncRNAs (false discovery rate < 0.05) per chromosome following 24 h activation of naive CD4+ T cells under Th1 conditions. Expression determined by bulk RNA-seq (n = 4). (B) Distribution of lncRNA expression in naive and activated (24 h, Th1 conditions) CD4+ T cells. (C) Expression versus LFC for all the differentially regulated lncRNAs. Dotted lines indicate LFC = 1 and FPKM = 20. (D) Expression heatmap of most highly expressed and differentially expressed lncRNAs. For downregulated, lncRNAs with LFC > 1 and naive CD4+ FPKM > 20 are shown. For upregulated, lncRNAs with LFC > 1 and Th1-activated CD4+ FPKM > 20 are shown. (E) Expression of Malat1 and Neat1 in naive and Th1-activated CD4+ T cells (24 h postactivation) determined by qRTPCR. Expression is normalized to U6 RNA and average expression in naive CD4+ T cells. (F) Malat1 expression determined in in vitro–differentiated Th0, Th1, and Th2 cells (day 6). Expression is normalized to U6 RNA and average expression in naive CD4+ T cells. (G) Malat1 expression during in vitro Th1 differentiation, normalized to naive CD4+ T cells.

We further investigated the list of highly expressed and differentially regulated lncRNAs and noticed that Malat1 (Fig. 1C) was the most highly expressed dysregulated lncRNA that was also conserved between the mouse and human genome (Gm26917 and Gm26836 were expressed at higher levels than Malat1 but have no obvious sequence or syntenic homologs in the human genome). Of note, Malat1 was within the top 2% most highly expressed transcripts in naive CD4+ T cells (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Malat1 suppression was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR (qRTPCR) (Fig. 1E). Neat1, an lincRNA adjacent to Malat1 in both mouse and human genome, was also found to be significantly downregulated within 24 h of CD4+ T cell activation by qRTPCR (Fig. 1E). The downregulation of Neat1 upon CD4+ T cell activation did not reach statistical significance in our RNA-seq analysis, likely because of higher variation and lower absolute expression of Neat1 compared with Malat1 in CD4+ T cells (Supplemental Fig. 1C). Suppression of Malat1 and Neat1 expression were also observed in end point (day 6) differentiated Th0-, Th1-, and Th2-polarizing conditions in vitro (Fig. 1F). Both Malat1 and Neat1 were downregulated within hours of naive CD4+ T cell activation (Fig. 1G, Supplemental Fig. 1D). The above results revealed that the rapid suppression of Malat1 and Neat1 expression is a key feature of the early lncRNA signature of CD4+ T cell activation.

Malat1 suppression is a transcriptomic hallmark of CD4+ T cell activation

To gain insight into whether Malat1 suppression was associated with CD4+ T cell function, we first analyzed a single-cell RNA-seq dataset we previously published exploring emergence of Th1 cells in vivo (17) using Plasmodium-specific TCR transgenic CD4+ T (PbTII) cells transferred into congenically labeled mice and recovered at days 2, 3, 4, and 7 postinfection (p.i.) with PcAS. In agreement with the observed suppression of Malat1 in our in vitro experiments (Fig. 1), we observed Malat1 and Neat1 downregulation upon CD4+ T cell activation in vivo, reaching a minimum at days 3 and 4, followed by a relative increase by day 7 (Fig. 2A, 2B). As observed in vitro, Neat1 expression was lower than Malat1 in Th1 cells in vivo (Fig. 2A, 2B).

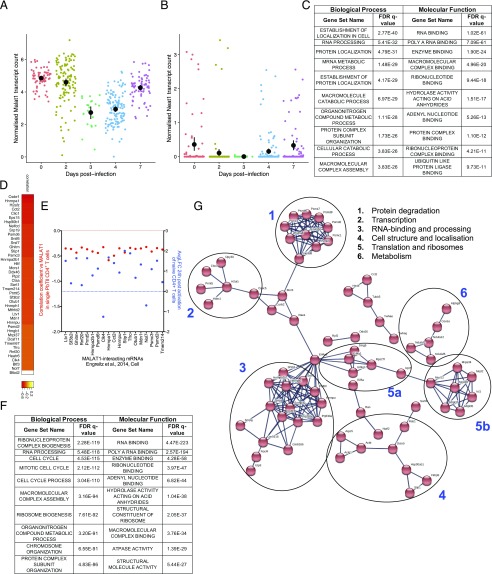

FIGURE 2.

Transcriptional units and transcription factors correlating with Malat1 expression at single-cell level in Th cells in vivo. (A) Normalized transcript counts of Malat1 in single Plasmodium-specific CD4+ T (PbTII) cells isolated at the indicated timepoints following infection with PcAS. Mean and 95% confidence intervals are shown. (B) Normalized transcript counts of Neat1 in single PbTII cells isolated at the indicated timepoints following infection with PcAS. Mean and 95% confidence intervals are shown. (C) Most highly enriched gene ontology (GO) terms among significantly negatively correlated (p < 0.05) genes with Malat1 in PbTII cells isolated from PcAS-infected mice (7 d p.i.). (D) Heatmap of correlation coefficients of Malat1 and indicated Malat1-interacting mRNAs (21, cell) in single PbTII cells from PcAS-infected mice 7 d p.i. (E) Correlation coefficient of Malat1 and indicated Malat1-interacting mRNAs (left y-axis, red) in single PbTII cells from PcAS-infected mice (7 d p.i.) versus average LFC following 24 h Th1 in vitro activation of naive CD4+ T cells (right y-axis, blue). Values are shown for significantly differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.05) following 24 h Th1 activation of naive CD4+ T cells. (F) Most highly enriched GO terms among significantly negatively correlated (p < 0.01) genes with Malat1 in single in vitro–differentiated Th2 cells. (G) STRING network of significantly correlated genes with Malat1 at single-cell levels in both in vivo PbTII Th1 and in vitro Th2 cells. Functional clusters are numbered and shown.

Next, we searched for transcriptomic units that show significant correlation with Malat1 expression at the single-cell level. We performed these analyses using the data from PbTII CD4+ T cells at day 7 p.i. because this is the time point that the strongest Th1 responses are observed (17). Analyses were performed in gated Th1 cells based on IFN-γ and CXCR6 expression rather than all CD4 PbTII cells at this time point. We searched for genes, the expression of which was positively or negatively correlated with that of Malat1. Strikingly, we found that from 687 genes that demonstrated significant correlation with Malat1 in Th1 cells, 609 (88.6%) correlated negatively (i.e., cells with low Malat1 levels demonstrate high levels of these genes). We noted that this was not purely due to the fact that Malat1 is downregulated in Th1 cells, as performing the same analysis for Lncpint, an lincRNA with similar basal expression in CD4+ T cells that is also downregulated upon activation (Fig. 1C) did not show a similar bias toward negative correlation (Supplemental Fig. 2A). Neat1 was within the positively correlated genes (Supplemental Fig. 2B), consistent with reports showing that the two lincRNAs are coregulated (18). Gene ontology analysis of the negatively correlated genes revealed significant enrichment in genes involved in RNA binding, ribosomal function, metabolism, and cellular structure/localization (Fig. 2C). We noted that these were processes associated with cellular activation and specifically naive CD4+ T cell differentiation to effector Th cells (19, 20). Analysis of a published set of Malat1-interacting mRNAs in embryonic stem cells (21) indicated that Malat1 has the potential to interact with the mRNA of 43 of the coregulated genes (Fig. 2D). Notably, 19 of these genes were also statistically significantly differentially expressed within 24 h of Th1 activation, with a dominant trend toward upregulation (Fig. 2E).

To assess whether the above Malat1-correlated gene signatures were specific to Th1 cells, we analyzed a single-cell RNA-seq dataset we previously published exploring gene expression in in vitro–polarized Th2 cells (22). Malat1 expression was significantly correlated with a higher number of genes in in vitro–differentiated Th2 cells (1946) than in Th1 cells from the PcAS-infected mice. As in the case of Th1 cells, the majority of statically significant correlations between expression of Malat1 and other genes were negative (1455 out of 1946, 74.8%). Similarly, to the observed results with Th1 cells, there was again a positive correlation between Malat1 and Neat1 (Supplemental Fig. 2C). Of note, Neat1 was the only gene neighboring Malat1 that showed a significant correlation with Malat1 in both Th1 and Th2 cells (Supplemental Fig. 2D), suggesting that Malat1 has limited in cis regulatory effects in Th cells. This was further supported by expression analyses in WT and Malat1−/− cells for Neat1 and Scyl1, the two chromosomally adjacent genes to Malat1. Neat1 levels were lower in naive Malat1−/− CD4+ T cells, and Scyl1 levels were higher in in vitro–differentiated Malat1−/− Th2 cells, but these effects were not consistent among the three cell types (Supplemental Fig. 2E). As in the case of single Th1 cells, gene ontology analysis of the negatively correlated genes revealed again significant enrichment in genes involved in RNA binding, ribosomal function, metabolism, and cell cycle (Fig. 2F). There were 152 genes that were significantly correlated with Malat1 in both single Th1 and Th2 cell–formed functional clusters with roles in RNA processing, ribosomal function, metabolism, and protein degradation (Fig. 2G, Supplemental Fig. 2F). Overall, these results indicated that, at the single-cell level, Malat1 suppression in Th cells correlated with induction of key gene networks upon CD4+ T cell activation.

Malat1 controls IL-10 expression in Th cells in vitro

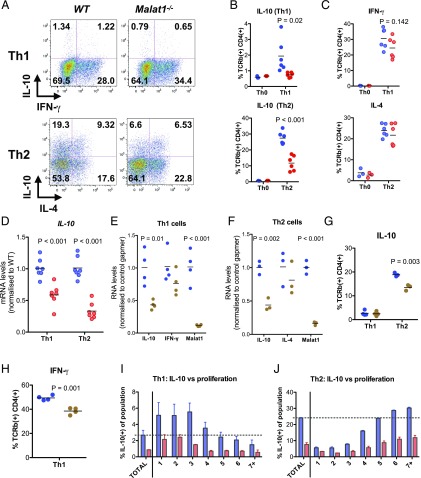

Having found that Malat1 suppression is a hallmark of Th activation, we tested the effect of Malat1 deletion on Th activation. We found that following in vitro differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells to Th1, Malat1−/− cells displayed a reduction in levels of IFN-γ that did not reach statistical significance but significantly reduced expression of the immunoregulatory cytokine IL-10. Upon Th2 differentiation, there was also a significant reduction in IL-10 levels, with IL-4 being unaffected (Fig. 3A–C). The effect on IL-10 was more prominent in Th2 cells, which express higher levels of IL-10 than Th1 cells in vitro (Fig. 3A, 3B). We also observed a reduction in IL-10 mRNA levels (Fig. 3D). We repeated these experiments under weakly polarizing conditions and found a statistically significant reduction upon Malat1 loss on IFN-γ expression in suboptimally activated Th1 cells but no effects on IL-10 or IL-4 and Il-10 under weakly polarizing Th2 conditions (Supplemental Fig. 3A). Malat1 loss also suppressed IL-10 and IL-17 expression under Th17-differentiation conditions (Supplemental Fig. 3B). In addition to genetic knockout of Malat1, targeting the RNA product of Malat1 with antisense oligonucleotide gapmers also suppressed IL-10 at the mRNA level in both Th1 and Th2 cells (Fig. 3E, 3F). The effect was also observed at the protein level in Th2 cells (Fig. 3G). In Th1 cells, gapmer-mediated inhibition of Malat1 resulted in a significant decrease in IFN-γ expression with no effects on IL-10 (Fig. 3H). Notably, we found that the suppression of IL-10 expression occurred in Malat1−/− CD4+ T cells irrespectively of how many times they have divided (Fig. 3I, 3J), demonstrating that the effect of Malat1 on IL-10 is decoupled from Th cell proliferation. Overall, these results demonstrated that Malat1 deficiency results in altered effector Th cell differentiation and cytokine expression in vitro, with a common effect among Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells being suppression of IL-10.

FIGURE 3.

Loss of Malat1 in in vitro–differentiated Th1 and Th2 cells results in suppression of IL-10 expression. (A) Representative FACS plots of IL-10 and IFN-γ or IL-10 and IL-4 expression in in vitro–differentiated Th1 and Th2 cells (day 6), respectively. (B) Percentage of IL-10+ live TCRβ+ CD4+ WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) Th1 or Th2 cells. Levels determined by intracellular cytokine staining. Levels in Th0 cells shown for reference (n = 6 for Th1 and Th2, and n = 3 for Th0). (C) Percentage of IFN-γ+ or IL-4+ live TCRβ+ CD4+ WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) Th1 or Th2 cells, respectively. Levels determined by intracellular cytokine staining. Levels in Th0 cells shown for reference (n = 6 for Th1 and Th2, and n = 3 for Th0). (D) IL-10 mRNA levels in in vitro–differentiated WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) Th1 and Th2 cells (day 6) determined by qRTPCR. Levels normalized to U6 and average levels in WT cells. (E) IL-10, IFN-γ, and Malat1 RNA levels in in vitro–differentiated Th1 cells (day 6) transfected with control (blue) or Malat1-targeting (brown) gapmer (100 nM). Levels normalized to U6 and average levels in cells transfected with control gapmer. (F) IL-10, IL-4, and Malat1 RNA levels in in vitro–differentiated Th2 cells (day 6) transfected with control (blue) or Malat1-targeting (brown) gapmer (100 nM). Levels normalized to U6 and average levels in cells transfected with control gapmer. (G) Percentage of IL-10+ live TCRβ+ CD4+ Th1 or Th2 cells transfected with control (blue) or Malat1-targeting (brown) gapmer (100 nM). Levels determined by intracellular cytokine staining on day 6. (H) Percentage of IFN-γ+ live TCRβ+ CD4+ Th1 cells transfected with control (blue) or Malat1-targeting (brown) gapmer (100 nM) (n = 4). (I) Percentage of IL-10+ CD4+ WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) Th1 cells (day 6) per cell division as determined by intracellular cytokine and CFSE staining (n = 4). (J) Percentage of IL-10+ CD4+ WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) Th2 cells (day 6) per cell division as determined by intracellular cytokine and CFSE staining (n = 4).

Loss of Malat1 impairs Maf expression in Th cells

To explore the mechanism employed by Malat1 to regulate IL-10, we determined the effect of Malat1 on transcription factors associated with Th cell activation and differentiation. Analysis of our single-cell RNA-seq data revealed 25 transcription factors that showed a significant correlation with Malat1 expression in Th1 cells from PcAS-infected mice (Fig. 4A). Notably, one of only three transcription factors that showed positive correlation with Malat1 was Maf (also known as c-Maf; Fig. 4B), a protein with fundamental roles in CD4+ T cell biology and, notably, an essential transcriptional regulator of IL-10 expression in Th cells (23–28). We also observed a positive correlation between Malat1 and Maf in single Th2 cells, which was borderline statistically nonsignificant (p = 0.0504; Fig. 4C). Despite a lack of a positive correlation between Malat1 and IL-10 in our single-cell analyses, possibly because of the low number of IL-10–expressing cells in the analyzed datasets (Supplemental Fig. 3C), Maf was one of only five genes positively correlating with expression of IL-10 and Malat1 in single Plasmodium-specific CD4+ T PbTII cells (Supplemental Fig. 3D). Investigating a list of previously published transcription factors correlating with IL-10 expression in CD4+ T cells (23) for overlap with genes correlated with Malat1 in single CD4+ T PbTII cells also identified Maf as the only gene present in both sets.

FIGURE 4.

Malat1 regulates Maf in Th cells. (A) Heatmap of correlation coefficients of significantly correlated transcription factors and coactivators (p < 0.05) and Malat1 expression by single PbTII cells isolated from PcAS-infected mice at day 7 p.i. (B) Normalized transcript count of Malat1 versus Maf in single PbTII cells isolated from PcAS-infected mice at day 7 p.i. (C) Normalized transcript count of Malat1 versus Maf in single in vitro–differentiated Th2 cells. (D) Maf mRNA levels in in vitro–differentiated WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) Th1 and Th2 cells (day 6) determined by qRTPCR. (E) Stat4 mRNA levels in in vitro–differentiated WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) Th1 cells (day 6). In (D) and (E), levels are determined by qRTPCR (n = 7) and normalized to U6 and average levels in WT cells. (F) Maf and Stat4 protein levels in WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) Th1 cells at days 4 or 6 postactivation determined by Western blot. (G) Maf mRNA levels during in vitro Th1 differentiation, normalized to naive CD4+ T cells. Levels normalized to U6 and average levels in naive CD4+ T cells. (H) Maf mRNA levels in Th1 or Th2 cells transfected with control (blue) or Malat1-targeting (brown) gapmer (100 nM). Levels normalized to U6 and average levels in cells transfected with control gapmer.

Next, we tested the effect of lack of Malat1 on levels of transcription factors with key roles in Th cell differentiation. Malat1 did not affect levels of Tbet in Th1 cells or Gata3 in Th2 cells (Supplemental Fig. 3E, 3F). However, Maf levels were reduced in both Th1 and Th2 cells, the effect reaching statistical significance in Th2 cells (Fig. 4D), which express higher levels of Maf than Th1 cells in vitro (Supplemental Fig. 3G). In Malat1−/− Th1 cells, we also observed a significant downregulation of Stat4 (Fig. 4E), with no changes observed in Stat6 in Th2 cells (Supplemental Fig. 3H). Of note, Stat4 is also known to promote IL-10 transcription in Th1 cells (29) and was also downregulated in Malat1−/− Th1 cells. At the protein level, we observed only a modest suppression of Stat4 expression in Malat1−/− Th1 cells at day 6 (Fig. 4F), whereas suppression of Maf was more pronounced than that observed at the mRNA level (Fig. 4D). Of note, the kinetics of Maf mRNA levels in Th1 cells demonstrated an early reduction followed by an increase (Fig. 4G), suggesting that Malat1 might be playing a role in Maf regulation at both the early and later stages of Th1 differentiation. Knockdown of Malat1 with gapmers suppressed Maf levels in both Th1 and Th2 cells, demonstrating that the effect is mediated by the Malat1 RNA (Fig. 4H). Furthermore, levels of Bhlhe40, a transcription factor involved IL-10 regulation (30) and anticorrelating with Malat1 (Fig. 4A), were not affected in Malat1−/− Th1 or Th2 cells (Supplemental Fig. 3I). Taken together, the above demonstrate that Malat1 loss suppresses expression of Maf, a central transcriptional regulator of IL-10 in Th cells.

Malat1−/− mice infected with L. donovani demonstrate reduced IL-10 expression in CD4+ T cells and lower parasite burden

Next, to explore the functional role of Malat1/Maf/IL-10 pathway in vivo, we studied the role of Malat1 in infection models in which IL-10 deficiency either promotes pathogen clearance or enhances immunopathology. First, we used L. donovani infection of mice as a model of pathogen-induced chronic inflammation (31). We chose to study a model of visceral leishmaniasis because Th1 cell–derived IL-10 has been previously shown to be a critical for protection and pathogen clearance but also a critical determinant of disease outcomes in humans (16, 32–36). Malat1 expression was reduced in CD4+ T cells isolated from spleens of infected mice compared with naive CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5A). Critically, we found that at the chronic infection stages (day 42 p.i.), IL-10 expression was reduced in splenic CD4+ T cells from infected Malat1−/− mice without any changes in IFN-γ expression (Fig. 5B–D), mirroring our findings from in vitro–activated CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4). There were no statistically significant changes in the number of splenic CD4+ T cells or frequency of naive (CD62L+/CD44−) and effector cells (CD62L−/CD44+) CD4+ T cells between WT and Malat1−/− mice (Supplemental Fig. 4A, 4B). The reduction in IL-10+ Th1 cells was accompanied with increased inducible NO synthase expression from splenic myeloid cells, particularly CD11b+/CCR2+/Ly-6Chi inflammatory monocytes in Malat1−/− mice (Fig. 5E). No changes in MHCII or IL-10 were found in any of the myeloid populations (Supplemental Fig. 4C, 4D). Critically, the observed reduction in IL-10 levels was accompanied by significantly reduced parasite loads in Malat1−/− mice (Fig. 5F, 5G) without any significant effects on spleen or liver size (Supplemental Fig. 4E). These results demonstrated that Malat1 regulates IL-10 in Th cells in vivo and that Malat1 deficiency can lead to enhanced protection during chronic L. donovani chronic infection.

FIGURE 5.

Loss of Malat1 results in suppression of IL-10 expression in Th1 cells in vivo and enhanced immunity to L. donovani. (A) Malat1 levels determined by qRTPCR in naive (N) CD4+ T cells and CD4+ T cells isolated from spleens of L. donovani–infected mice (day 28) p.i. Levels normalized to U6 and average levels in N CD4+ T cells. (B) Representative FACS plots of IL-10 and IFN-γ expression in splenic CD4+ T cells from L. donovani–infected WT and Malat1−/− mice (day 42 p.i.) following restimulation with PMA/ionomycin. (C) Percentage of IL-10+ live TCRβ+ CD4+ cells from L. donovani–infected WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) mice (day 42 p.i.), determined by intracellular cytokine staining. Levels from noninfected N mice are also shown for reference. Levels are shown in cells directly postisolation (brefeldin A [bref] alone) or following restimulation with PMA and ionomycin (PMA/iono). (D) Percentage of IFN-γ+ live TCRβ+ CD4+ cells from L. donovani infected WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) mice (day 42 p.i.), determined by intracellular cytokine staining. Levels from noninfected N mice are also shown for reference. Levels are shown in cells directly postisolation (bref alone) or following restimulation with PMA/iono. (E) Percentage of inducible NO synthase-positive (iNOS+) myeloid live cells from spleens of noninfected (N) or L. donovani–infected WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) mice (day 42 p.i.; n = 5). (F) Spleen and liver parasite counts per 1000 nuclei from L. donovani–infected WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) mice (day 42 p.i.). (G) Spleen and liver Leishman–Donovan units from L. donovani–infected WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) mice (day 42 p.i.). For (C), (D), (F), and (G), n = 11, and for (E), n = 5.

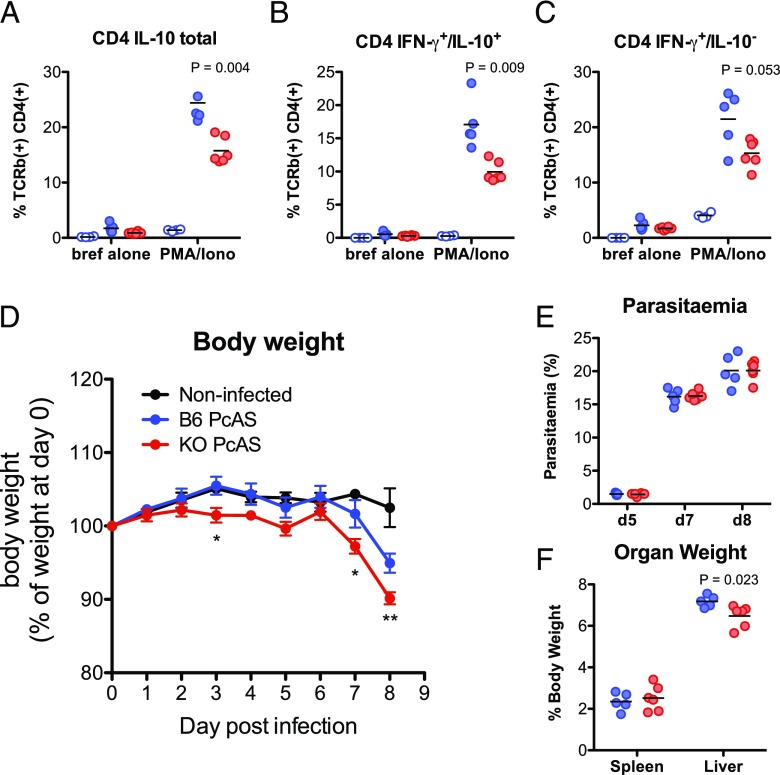

PcAS-infected Malat1−/− mice demonstrate reduced Th1 IL-10 expression and more severe disease

To further test the functional relevance of Malat1-mediated IL-10 regulation in vivo, we infected Malat1−/− and WT mice with PcAS. IL-10 plays a prominent role in the outcome of malaria disease in humans (37, 38), and in the PcAS experimental model of malaria, IL-10 deficiency promotes severe disease manifested as more pronounced weight loss and mortality (39). As in the case of L. donovani infection, CD4+ T cells from spleens of PcAS-infected Malat1−/− mice demonstrated lower IL-10 expression (Fig. 6A, 6B). A borderline nonsignificant trend toward reduction in IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells was also observed (Fig. 6C). Crucially, more pronounced weight loss was observed in Malat1−/− mice compared with WT controls within the first week of PcAS infection (Fig. 6D). Of note, the experiment had to be terminated because of the increased rate of weight loss in Malat1−/− mice (expected to exceed 20% of starting body weight by day 9) and lack of touch escape and pinna reflexes in Malat1−/− at day 8 (median score of 0 out of 2 for both). We did not observe any effects on parasitemia (Fig. 6E). Spleen enlargement was similar between WT and Malat1−/− mice, but a modest reduction liver size in PcAS-infected Malat1−/− mice was observed (Fig. 6F). Of note, Malat1 did not affect IL-10 and IFN-γ levels in CD8+ T cells in infected mice (Supplemental Fig. 4F, 4G). The above findings further demonstrated the role of Malat1 in regulation of IL-10 in Th cells in vivo and supported that the extent of Malat1 downregulation and its expression kinetics during Plasmodium infections can be a significant determinant of infectious disease outcome.

FIGURE 6.

Loss of Malat1 results in suppression of IL-10 expression in Th1 cells and more severe disease in PcAS-infected mice. (A) Percentage of IL-10+ live TCRβ+ CD4+ cells from PcAS-infected WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) mice (day 8 p.i.), determined by intracellular cytokine staining. Levels from noninfected naive (N) mice are also shown for reference. Levels are shown in cells directly postisolation (brefeldin A [bref] alone) or following restimulation with PMA and ionomycin (PMA/iono). (B) As in (A) but for percentage of IFN-γ+/IL-10+ live TCRβ+ CD4+ cells from PcAS-infected WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) mice (day 8 p.i.). (C) As in (A) but for percentage of IFN-γ−/IL-10+ live TCRβ+ CD4+ cells from PcAS-infected WT (blue) or Malat1−/− (red) mice (day 8 p.i.). (D) Body weight of PcAS-infected WT (B6, blue) or Malat1−/− (red) mice on indicated days p.i. Weight expressed as percentage of starting weight for each mouse. Black line shows weights of noninfected mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, between infected WT and Malat1−/− mice. (E) Parasitemia (percentage of infected cells) in PcAS-infected WT (B6, blue) or Malat1−/− (red) mice on indicated days p.i. (F) Spleen and liver weights as percentage of body weight in PcAS-infected WT (B6, blue) or Malat1−/− (red) mice at day 8 p.i. For (A)–(F), n = 4–6.

Discussion

Despite its high abundance and conservation, the physiological function of Malat1 at the whole organism level has remained elusive. We demonstrate that regulation of adaptive immunity is one of the essential functions of this unique noncoding RNA. We show that suppression of Malat1, one of the most highly expressed transcripts in naive CD4+ T cells, is a hallmark of Th1 and Th2 activation, but its complete deletion results in altered Th cell phenotype and enhanced Th cell responses in vivo, which can lead to protection from infection but also severe immunopathology. It is possible that suppression of Malat1 can be due to dilution occurring during the initial transcriptional burst at the early stages of naive CD4+ T cell activation. This would mean that there are transcriptional mechanisms excluding Malat1, a very highly expressed and transcribed transcript, from this general burst. We note that these mechanisms would be specific to Malat1, as we show that the expression of other highly expressed lncRNAs is not altered or diluted upon naive CD4+ T cell activation (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, Malat1 suppression is sustained up to 6 d postactivation, suggesting the existence of active transcriptional suppression and/or posttranscriptional destabilization mechanisms regulating its expression in Th cells. The observed inverse correlation between Malat1 expression and transcriptional signatures associated with cellular activation in single Th cells might signify that high Malat1 expression is necessary for maintenance of the naive CD4+ T cell state or that suppressed Malat1 expression is required for appropriate Th cell differentiation. The seeming contradiction between our findings and those reported by Yao and colleagues (14) during acute LCMV infection can be explained by the predominant focus of that study on CD8+ T cell responses and the fact that IL-10 determines susceptibility to infection only in chronic LCMV infection models (40). In our study, the effect of Malat1 on IL-10 expression is observed both in in vitro differentiated Th cells and in vivo in two distinct infection models progressing at significantly different timescales (days for PcAS versus weeks for L. donovani), demonstrating a CD4+ T cell–intrinsic regulatory role for Malat1. We note that because of the use of a full Malat1−/− mouse, we cannot exclude other CD4+ T cell–independent mechanism contributing to L. donovani clearance or PcAS-induced immunopathology. However, we propose that despite its widespread expression across tissues, Malat1 has striking CD4+ T cell–specific functions, one of which involves promoting Maf and IL-10 expression.

It is thought that Malat1 controls gene expression through interacting with multiple RBPs (9, 21, 41, 42). Our experiments with Malat1 inhibitors confirmed that the Malat1 RNA is responsible for altered Th cell differentiation. We note that we observed slight differences between the effect of Malat1 knockout and that of knockdown in Th1 cells (e.g., with regards to IFN-γ expression). These observations can be the result of the fact that Malat1 is deleted in naive CD4+ T Malat1−/− cells before they are activated, whereas in cells treated with gapmers, depletion occurs concurrently with activation and endogenous downregulation of Malat1. In any case, we show that inhibiting or deleting Malat1 can lead to reduction of IL-10 and Maf expression in vitro and in vivo. We propose that the specificity of Malat1 functions in CD4+ T cells is mediated through a network of interactions between Malat1 and RBPs, which, in turn, have cell-type specific RNA targets and functions (43). Indeed, we anticipate that Malat1 functions in Th cell differentiation are likely to extend beyond regulation of Maf and IL-10. The work presented in this study reveals one mechanism employed by Malat1 to shape immunity to infection and indicates that this lncRNA, like IL-10, plays a critical role in controlling the fragile equilibrium between effective pathogen clearance and enhanced immunopathology. Our work suggests that exploring how Malat1-binding RBPs regulate Maf and IL-10 expression through Malat1-dependent or -independent mechanisms can provide key insight into the posttranscriptional regulation of this critical immunoregulatory axis.

Implicating Malat1 in the regulation of IL-10 can have far-reaching consequences. Although all activated (effector and regulatory) CD4+ T cells express IL-10 at some point of their differentiation trajectory (26), the magnitude and kinetics of expression differ drastically between subsets. Yet, despite significant progress on the transcriptional cues that initiate and maintain IL-10 expression in CD4+ T cells, much less is known about the molecular controllers that ensure accurate timing and magnitude of IL-10 expression. Our work supports that Malat1 plays a key role in the complex process that ensures optimal IL-10 levels. Notably, the high abundance of Malat1 in naive CD4+ T cells is evolutionary-compatible with this role. Although Malat1 expression is reduced early during CD4+ T cell activation, its high absolute abundance means that there is still a significant Malat1 pool within effector Th cells to allow for appropriate IL-10 expression. This provides a flexible molecular mechanism of regulating immune responses mediated by Malat1, a major component of the CD4+ T cell noncoding transcriptome. Although predominantly focused on Th1 and Th2 cells, our work suggests that Malat1 might be a significant functional determinant of other Maf- and IL-10–expressing immune cell types, such as regulatory T cells (44), follicular Th cells (45, 46), or innate lymphoid cells (47).

Overall, our findings reveal Malat1 as a negative regulator of immunity to infection. We uncover the functional significance of Malat1 in the context of two major parasitic infectious diseases, malaria and visceral leishmaniasis, providing new insight into molecular determinants of disease susceptibility. We speculate that through its fundamental role in Th cell differentiation and function, Malat1 is likely to govern immune responses and disease outcomes in a broad range of infectious, autoimmune, or inflammatory pathological conditions, reflecting the centrality of the noncoding transcriptome in the immune system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jean Langhorne for the PcAS parasites and advice. We thank staff at the Imaging and Cytometry and Genomics and Bioinformatics Labs in the University of York Bioscience Technology Facility for technical support and advice.

The work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (Institutional Strategic Support Fund Grant WT204829 through the Centre for Future Health at the University of York, Senior Investigator Award WT1063203 [to P.M.K.], and WT206194); the U.K. Medical Research Council (MR/L008505/1) (to D.L.); and the European Research Council (Grant 646794 to S.A.T.). K.R.J. receives financial support from Christ’s College, University of Cambridge. K.A.W. is funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council White Rose doctoral training partnership (BB/J014443/1).

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

- FPKM

- fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads

- LCMV

- lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

- LFC

- log2 fold change

- lincRNA

- long intergenic noncoding RNA

- lncRNA

- long noncoding RNA

- Malat1

- metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1

- MHCII

- MHC class II

- PbTII

- Plasmodium-specific TCR transgenic CD4+ T

- PcAS

- Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi AS

- qRTPCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- RBP

- RNA-binding protein

- RNA-seq

- RNA sequencing

- STRING

- Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Engreitz J. M., Ollikainen N., Guttman M. 2016. Long non-coding RNAs: spatial amplifiers that control nuclear structure and gene expression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17: 756–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long Y., Wang X., Youmans D. T., Cech T. R. 2017. How do lncRNAs regulate transcription? Sci. Adv. 3: eaao2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy K. M., Stockinger B. 2010. Effector T cell plasticity: flexibility in the face of changing circumstances. Nat. Immunol. 11: 674–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Y. G., Satpathy A. T., Chang H. Y. 2017. Gene regulation in the immune system by long noncoding RNAs. Nat. Immunol. 18: 962–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu G., Tang Q., Sharma S., Yu F., Escobar T. M., Muljo S. A., Zhu J., Zhao K. 2013. Expression and regulation of intergenic long noncoding RNAs during T cell development and differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 14: 1190–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranzani V., Rossetti G., Panzeri I., Arrigoni A., Bonnal R. J., Curti S., Gruarin P., Provasi E., Sugliano E., Marconi M., et al. 2015. The long intergenic noncoding RNA landscape of human lymphocytes highlights the regulation of T cell differentiation by linc-MAF-4. Nat. Immunol. 16: 318–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez J. A., Wapinski O. L., Yang Y. W., Bureau J. F., Gopinath S., Monack D. M., Chang H. Y., Brahic M., Kirkegaard K. 2013. The NeST long ncRNA controls microbial susceptibility and epigenetic activation of the interferon-γ locus. Cell 152: 743–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutschner T., Hämmerle M., Eissmann M., Hsu J., Kim Y., Hung G., Revenko A., Arun G., Stentrup M., Gross M., et al. 2013. The noncoding RNA MALAT1 is a critical regulator of the metastasis phenotype of lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 73: 1180–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tripathi V., Ellis J. D., Shen Z., Song D. Y., Pan Q., Watt A. T., Freier S. M., Bennett C. F., Sharma A., Bubulya P. A., et al. 2010. The nuclear-retained noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates alternative splicing by modulating SR splicing factor phosphorylation. Mol. Cell 39: 925–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamond A. I., Spector D. L. 2003. Nuclear speckles: a model for nuclear organelles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4: 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eißmann M., Gutschner T., Hämmerle M., Günther S., Caudron-Herger M., Groß M., Schirmacher P., Rippe K., Braun T., Zörnig M., Diederichs S. 2012. Loss of the abundant nuclear non-coding RNA MALAT1 is compatible with life and development. RNA Biol. 9: 1076–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakagawa S., Ip J. Y., Shioi G., Tripathi V., Zong X., Hirose T., Prasanth K. V. 2012. Malat1 is not an essential component of nuclear speckles in mice. RNA 18: 1487–1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang B., Arun G., Mao Y. S., Lazar Z., Hung G., Bhattacharjee G., Xiao X., Booth C. J., Wu J., Zhang C., Spector D. L. 2012. The lncRNA Malat1 is dispensable for mouse development but its transcription plays a cis-regulatory role in the adult. Cell Rep. 2: 111–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao Y., Guo W., Chen J., Guo P., Yu G., Liu J., Wang F., Liu J., You M., Zhao T., et al. 2018. Long noncoding RNA Malat1 is not essential for T cell development and response to LCMV infection. RNA Biol. 15: 1477–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masoumi F., Ghorbani S., Talebi F., Branton W. G., Rajaei S., Power C., Noorbakhsh F. 2019. Malat1 long noncoding RNA regulates inflammation and leukocyte differentiation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neuroimmunol. 328: 50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hewitson J. P., Shah K. M., Brown N., Grevitt P., Hain S., Newling K., Sharp T. V., Kaye P. M., Lagos D. 2019. miR-132 suppresses transcription of ribosomal proteins to promote protective Th1 immunity. EMBO Rep. DOI: 10.15252/embr.201846620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lönnberg T., Svensson V., James K. R., Fernandez-Ruiz D., Sebina I., Montandon R., Soon M. S., Fogg L. G., Nair A. S., Liligeto U., et al. 2017. Single-cell RNA-seq and computational analysis using temporal mixture modelling resolves Th1/Tfh fate bifurcation in malaria. [Published erratum appears in 2018 Sci. Immunol. DOI: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aat1469.] Sci. Immunol. DOI: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aal2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.West J. A., Davis C. P., Sunwoo H., Simon M. D., Sadreyev R. I., Wang P. I., Tolstorukov M. Y., Kingston R. E. 2014. The long noncoding RNAs NEAT1 and MALAT1 bind active chromatin sites. Mol. Cell 55: 791–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buck M. D., O’Sullivan D., Pearce E. L. 2015. T cell metabolism drives immunity. J. Exp. Med. 212: 1345–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox C. J., Hammerman P. S., Thompson C. B. 2005. Fuel feeds function: energy metabolism and the T-cell response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5: 844–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engreitz J. M., Sirokman K., McDonel P., Shishkin A. A., Surka C., Russell P., Grossman S. R., Chow A. Y., Guttman M., Lander E. S. 2014. RNA-RNA interactions enable specific targeting of noncoding RNAs to nascent Pre-mRNAs and chromatin sites. Cell 159: 188–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahata B., Zhang X., Kolodziejczyk A. A., Proserpio V., Haim-Vilmovsky L., Taylor A. E., Hebenstreit D., Dingler F. A., Moignard V., Göttgens B., et al. 2014. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals T helper cells synthesizing steroids de novo to contribute to immune homeostasis. Cell Rep. 7: 1130–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabryšová L., Alvarez-Martinez M., Luisier R., Cox L. S., Sodenkamp J., Hosking C., Pérez-Mazliah D., Whicher C., Kannan Y., Potempa K., et al. 2018. c-Maf controls immune responses by regulating disease-specific gene networks and repressing IL-2 in CD4+ T cells. [Published erratum appears in 2019 Nat. Immunol. 20: 374.] Nat. Immunol. 19: 497–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho I. C., Lo D., Glimcher L. H. 1998. c-maf promotes T helper cell type 2 (Th2) and attenuates Th1 differentiation by both interleukin 4-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J. Exp. Med. 188: 1859–1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pot C., Jin H., Awasthi A., Liu S. M., Lai C. Y., Madan R., Sharpe A. H., Karp C. L., Miaw S. C., Ho I. C., Kuchroo V. K. 2009. Cutting edge: IL-27 induces the transcription factor c-Maf, cytokine IL-21, and the costimulatory receptor ICOS that coordinately act together to promote differentiation of IL-10-producing Tr1 cells. J. Immunol. 183: 797–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saraiva M., O’Garra A. 2010. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10: 170–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trinchieri G. 2007. Interleukin-10 production by effector T cells: Th1 cells show self control. J. Exp. Med. 204: 239–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu J., Yang Y., Qiu G., Lal G., Wu Z., Levy D. E., Ochando J. C., Bromberg J. S., Ding Y. 2009. c-Maf regulates IL-10 expression during Th17 polarization. J. Immunol. 182: 6226–6236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saraiva M., Christensen J. R., Veldhoen M., Murphy T. L., Murphy K. M., O’Garra A. 2009. Interleukin-10 production by Th1 cells requires interleukin-12-induced STAT4 transcription factor and ERK MAP kinase activation by high antigen dose. Immunity 31: 209–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huynh J. P., Lin C. C., Kimmey J. M., Jarjour N. N., Schwarzkopf E. A., Bradstreet T. R., Shchukina I., Shpynov O., Weaver C. T., Taneja R., et al. 2018. Bhlhe40 is an essential repressor of IL-10 during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 215: 1823–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaye P., Scott P. 2011. Leishmaniasis: complexity at the host-pathogen interface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9: 604–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson C. F., Oukka M., Kuchroo V. J., Sacks D. 2007. CD4(+)CD25(-)Foxp3(-) Th1 cells are the source of IL-10-mediated immune suppression in chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Exp. Med. 204: 285–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gautam S., Kumar R., Maurya R., Nylén S., Ansari N., Rai M., Sundar S., Sacks D. 2011. IL-10 neutralization promotes parasite clearance in splenic aspirate cells from patients with visceral leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Dis. 204: 1134–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy M. L., Wille U., Villegas E. N., Hunter C. A., Farrell J. P. 2001. IL-10 mediates susceptibility to Leishmania donovani infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 31: 2848–2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nylén S., Maurya R., Eidsmo L., Manandhar K. D., Sundar S., Sacks D. 2007. Splenic accumulation of IL-10 mRNA in T cells distinct from CD4+CD25+ (Foxp3) regulatory T cells in human visceral leishmaniasis. J. Exp. Med. 204: 805–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owens B. M., Beattie L., Moore J. W., Brown N., Mann J. L., Dalton J. E., Maroof A., Kaye P. M. 2012. IL-10-producing Th1 cells and disease progression are regulated by distinct CD11c+ cell populations during visceral leishmaniasis. PLoS Pathog. 8: e1002827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Couper K. N., Blount D. G., Riley E. M. 2008. IL-10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J. Immunol. 180: 5771–5777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar R., Ng S., Engwerda C. 2019. The role of IL-10 in malaria: a double edged sword. Front. Immunol. 10: 229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li C., Corraliza I., Langhorne J. 1999. A defect in interleukin-10 leads to enhanced malarial disease in Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 67: 4435–4442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richter K., Perriard G., Oxenius A. 2013. Reversal of chronic to resolved infection by IL-10 blockade is LCMV strain dependent. Eur. J. Immunol. 43: 649–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen R., Liu Y., Zhuang H., Yang B., Hei K., Xiao M., Hou C., Gao H., Zhang X., Jia C., et al. 2017. Quantitative proteomics reveals that long non-coding RNA MALAT1 interacts with DBC1 to regulate p53 acetylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 45: 9947–9959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spiniello M., Knoener R. A., Steinbrink M. I., Yang B., Cesnik A. J., Buxton K. E., Scalf M., Jarrard D. F., Smith L. M. 2018. HyPR-MS for multiplexed discovery of MALAT1, NEAT1, and NORAD lncRNA protein interactomes. J. Proteome Res. 17: 3022–3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner M., Díaz-Muñoz M. D. 2018. RNA-binding proteins control gene expression and cell fate in the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 19: 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wheaton J. D., Yeh C. H., Ciofani M. 2017. Cutting edge: c-Maf is required for regulatory T cells to adopt RORγt+ and follicular phenotypes. J. Immunol. 199: 3931–3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andris F., Denanglaire S., Anciaux M., Hercor M., Hussein H., Leo O. 2017. The transcription factor c-Maf promotes the differentiation of follicular helper T cells. Front. Immunol. 8: 480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xin G., Zander R., Schauder D. M., Chen Y., Weinstein J. S., Drobyski W. R., Tarakanova V., Craft J., Cui W. 2018. Single-cell RNA sequencing unveils an IL-10-producing helper subset that sustains humoral immunity during persistent infection. Nat. Commun. 9: 5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seehus C. R., Kadavallore A., Torre B., Yeckes A. R., Wang Y., Tang J., Kaye J. 2017. Alternative activation generates IL-10 producing type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Commun. 8: 1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.