Abstract

Intrinsic optical signal (IOS) imaging has been widely used to map the patterns of brain activity in vivo in a label-free manner. Traditional IOS refers to changes in light transmission, absorption, reflectance, and scattering of the brain tissue. Here, we use polarized light for IOS imaging to monitor structural changes of cellular and subcellular architectures due to their neuronal activity in isolated brain slices. To reveal fast spatiotemporal changes of subcellular structures associated with neuronal activity, we developed the instantaneous polarized light microscope (PolScope), which allows us to observe birefringence changes in neuronal cells and tissues while stimulating neuronal activity. The instantaneous PolScope records changes in transmission, birefringence, and slow axis orientation in tissue at a high spatial and temporal resolution using a single camera exposure. These capabilities enabled us to correlate polarization-sensitive IOS with traditional IOS on the same preparations. We detected reproducible spatiotemporal changes in both IOSs at the stratum radiatum in mouse hippocampal slices evoked by electrical stimulation at Schaffer collaterals. Upon stimulation, changes in traditional IOS signals were broadly uniform across the area, whereas birefringence imaging revealed local variations not seen in traditional IOS. Locations with high resting birefringence produced larger stimulation-evoked birefringence changes than those produced at low resting birefringence. Local application of glutamate to the synaptic region in CA1 induced an increase in both transmittance and birefringence signals. Blocking synaptic transmission with inhibitors CNQX (for AMPA-type glutamate receptor) and D-APV (for NMDA-type glutamate receptor) reduced the peak amplitude of the optical signals. Changes in both IOSs were enhanced by an inhibitor of the membranous glutamate transporter, DL-TBOA. Our results indicate that the detection of activity-induced structural changes of the subcellular architecture in dendrites is possible in a label-free manner.

Significance

Intrinsic optical signal (IOS) imaging has been widely used to map patterns of brain activity without the use of labels. However, existing IOS imaging is not sensitive to cellular and subcellular changes associated with neuronal activity. We are proposing to expand IOS imaging modalities by including polarized light analysis for observing hitherto undetected structural changes of the cellular and subcellular architectures caused by their neuronal activity. We developed imaging systems with reproducible spatial and temporal resolution that can monitor activity-induced birefringence changes in hippocampal slices that are closely related to subcellular architectures in postsynaptic neurons. Polarized light imaging has the potential to enhance existing IOS imaging by bringing structural insights into IOS changes induced by neuronal activity in the brain.

Introduction

Intrinsic optical signal (IOS) imaging has been used as one of the most promising label-free approaches to map the patterns of brain activity in vivo and ex vivo (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). Traditional IOS refers to changes in optical transmission, scattering, and reflectance of the tissue. These optical changes in the brain in vivo are associated with alterations in the balance of oxy- and deoxyhemoglobins (1,2), blood volume (7), swelling of neurons (8, 9, 10), changes in ionic metabolism in astrocytes (11,12), and flavin metabolisms (13, 14, 15, 16) that are correlated with neuronal activity. In ex vivo (isolated) brain slice preparations, neuronal swelling is thought to be the major cause of IOS in response to electrical stimulations of neurons (8, 9, 10,12). Past studies indicated that morphological changes of organelles such as mitochondria (11,17,18) and intracellular vesicles (19,20) contribute to traditional IOS changes in primary cultured neurons and isolated neuronal tissues.

Polarized light microscopy has been a powerful tool to investigate the anisotropic structural signatures of molecular assemblies and their dynamics in living cells in a label-free and noninvasive manner (21). The biological polarized light microscope was developed more than half a century ago to observe the assembly and disassembly of protein polymers that produce mechanical forces for segregating chromosomes in the process of cell division (22,23). Later, an advanced polarizing microscope, the liquid-crystal-based polarized light microscope (LC-PolScope), was built based on the traditional polarizing microscope, introducing two essential modifications: the specimen is illuminated with nearly circularly polarized light, and the traditional compensator is replaced by a liquid-crystal-based universal compensator (24). As with the traditional polarizing microscope, the LC-PolScope enables the observation of ordered structures of cellular and subcellular components such as the cytoskeleton and lipid membranes without treating cells with exogenous dyes or fluorescent labels (25, 26, 27), albeit at a much higher sensitivity. By taking advantage of the high sensitivity and quantitative nature of LC-PolScope images, we have shown the anatomical structures of the brain composed of both myelinated and nonmyelinated axons and dendrites and their developmental changes in acute slice preparations of chick cerebellum (27).

Despite its usefulness and reliability in quantitatively mapping quasistatic birefringent structures in living cells, the total acquisition time of ∼1 s for LC-PolScope images is too long for mapping neuronal activity signals. Therefore, we developed the instantaneous PolScope, which simultaneously records all four images required for mapping the optical anisotropy of observed objects using a four-way polarizing beam splitter in the imaging optics. The setup was first implemented for the instantaneous FluoPolScope developed in our laboratory (28). The time resolution of the new microscope is as fast as 10 ms or 100 Hz, enabling us to monitor synaptically evoked changes in relative birefringence and transmittance of the stratum radiatum of area CA1 in mouse hippocampal slices. By monitoring both changes in transmittance and birefringence, we were able to reveal local changes of relative birefringence that originated from cellular or subcellular changes in neuronal structures that cannot be observed with the transmittance changes. We applied a series of drugs that block glutamate receptors and transporters to identify the origins of transient changes in the optical properties of hippocampal slices.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval

All experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved by the Marine Biological Laboratory. Animal experiments were performed on brain tissue from male and female CD-1 mice (Charles River, Boston, MA) of postnatal day 4–20 weeks of age, housed in the animal facility at the Marine Biological Laboratory. Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and then quickly decapitated.

Preparation of brain slices and solutions

After the decapitation, the isolated brain was quickly transferred on ice-cold cutting solution containing 205.4 mM sucrose, 2.5 mM KCl, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 0.4 mM CaCl2, 4 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM glucose (pH 7.4 when bubbled with a moistened mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% O2). After cooling the brain on ice for 5 min, the hippocampus together with surrounding cortex was sliced in 250-μm thick slices using a linear slicer (Pro-7; Dosaka, Kyoto, Japan). Each slice was transferred onto a membrane filter (pore size, 0.45 μm; Omnipore, Merck Millipore, MA) after a short incubation in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing 124 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM glucose (pH 7.4 when bubbled with a moistened mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% O2). Brain slices placed on membrane filters were incubated in a moist chamber at room temperature (22–26°C) until imaging. Cyanquixaline (CNQX), (2R)-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (D-APV), bicuculline, DL-threo-β-benzyloxyaspartic acid (TBOA), dihydrokainic acid, and tetrodotoxin (TTX) were purchased from Tocris (Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN).

Primary culture

Cultured hippocampal neurons were prepared from postnatal 1- to 3-day-old C57BL/6 mice. After anesthetization by inhalation of isoflurane, the pups were quickly decapitated. Hippocampi were dissected out and maintained in Earle’s balanced salt solution containing papain for 30 min at 37°C. The hippocampi were transferred to the culture media contained Neurobasal A medium, B27 supplement, and 5% fetal bovine serum (all from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and then gently dissociated using a fire-polished glass pipette. The dissociated cells were plated on poly-D-lysine-coated coverslips and maintained in culture media at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Twice a week, half of the culture medium was replaced with new medium. The cultured neurons were used for imaging between 7 and 14 days after plating.

Slice preparation setting and nerve stimulation

The brain slices were gently transferred into the imaging chamber (chamber volume, ∼1 mL) under the dissecting microscope. During imaging, the slices were continuously perfused with ACSF at a rate of 1 mL per min. ACSF was continuously bubbled with mixture of 5% CO2/95% O2 gas and warmed to 37°C with an in-line temperature-controlling device (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). An ACSF-filled glass pipette (opening diameter of 10–30 μm, 1B120F-4; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) was used for Schaffer collateral nerve stimulations. The stimulus train (250 μA, 1-ms pulse duration, 50 pulses, 40 Hz) was generated by a pulse generator (B&K Precision, Yorba Linda, CA) through an isolator (World Precision Instruments) to induce IOS changes. For imaging birefringence of single neurons in hippocampus slices, we prepared ACSF with 54% of iodixanol by mixing 10× concentrated ACSF with 60% of iodixanol (Optiprep; STEMCELL Technologies, MA, USA).

LC-PolScope imaging

The principles of LC-PolScope imaging were described elsewhere (21). The brain slice was illuminated with a direct-current-stabilized 100-W tungsten halogen lamp through a band-pass filter (529/24 nm; Semrock, Rochester, NY). Slice images were captured with a CCD camera (Retiga 2000RV; QImaging, Burnaby, Canada). A 20× water-dipping lens (XLUMPLANFL 20×, NA 0.95; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), 4× dry lens (XL FLUOR 4×, NA 0.28; Olympus), or 60× Nikon oil immersion lens (PlanApo VC 60×, NA1.4; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) was used for the LC-PolScope imaging. The universal compensator in the optical path of the LC-PolScope includes two liquid crystal variable retarders and a polarizer. Several predetermined polarization settings can be registered in the controller of the universal compensator and are used to sequentially acquire five raw images. Images of the hippocampal slice, taken with four elliptical polarization illumination axes (0, 45, 90, and 135°), and an image taken with the extinction illumination setting in which the polarization of the illumination has opposite handedness with respect to that of the circular analyzer (Fig. 1 B) were used to obtain the retardance map (Fig. 1 C) and the slow axis orientation map (Fig. 1 D; (29)). The pseudocolored map of the hippocampal slice (Fig. 1 D) encodes the retardance as brightness and the slow axis orientation as hue. Images of the four elliptical polarization illumination settings were sequentially captured, and the averaged image was shown as transmittance (Fig. 1 A), which was obtained as follows: the transmittance image in Fig. 1 A was computed based on the four images IS1 through IS4 for the sample and the background using the following formula:

Figure 1.

Polarized light images of a mouse hippocampal slice recorded with the LC-PolScope. An objective lens, Olympus XL FLUOR 4×, NA 0.28, was used. (A) The transmitted light image shows the stratum oriens (s.o.), stratum pyramidale (s.p.), stratum radiatum (s.r.), stratum lacunosum-moleculare (s.l.m.), stratum lucidum (s.l), molecular layer (m.l), and granule cell layer (g.c.l). (B) A raw LC-PolScope image using only the extinction illumination setting (S0) is shown. Note that the bright image of the m.l in the dentate gyrus that appears bright in (A) appears as a dark image in the extinction setting image. (C) A retardance map generated using all five raw LC-Polscope images is shown. Image brightness is proportional to local retardance values. The inset on the bottom left shows the reference for local retardance values. (D) A pseudocolor image that combines retardance (brightness) and slow axis orientation (color) is shown. The color wheel on the bottom left shows the reference for the local slow axis orientation of birefringence. White arrowheads in (C) and (D) indicate the axonal projections from the layer III entorhinal cortex neurons to distal dendrites of CA1 pyramidal cells. Scale bars in (A)–(D), 100 μm. (E) An analysis of optical properties across multiple strata at area CA1 (enclosed by white broken rectangles in A–D) is shown. Intensity profiles are taken with four different elliptical polarization illumination settings (S1–S4, black), extinction illumination setting (S0, green), slow axis orientation (red), and retardance value (dark blue). The inset at the bottom is the cropped image enclosed by the white broken rectangle in (A). Scale bars, 100 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

For image computation and analysis, we used the OpenPolScope plug-ins for the open source image analysis platforms ImageJ and Micro-Manager (30).

Plots of transmittance and retardance values over time were drawn as normalized values of the selected areas. Normalized values at each time point were obtained by dividing them by the average value at resting level (5–10 frames before the stimulation).

Instantaneous PolScope imaging

The instantaneous PolScope is a modification of the instantaneous FluoPolScope that we developed for monitoring the position and orientation of single-emission dipoles of fluorophores in living cells (28). For the instantaneous PolScope, we use the same polarizing splitters in the imaging path as described in (28). For illumination, however, we use the transmitted light path, providing incoming light from a LED (M530D2; Thorlabs, Newton, NJ) through the condenser optics, equipped with and without a polarizer for circularly polarized light. Without a polarizer, the illuminating light is unpolarized, and the transmitted light is analyzed for linear polarization along four orientations, i.e., 0, 45, 90, and 135°. With a polarizer in the illumination path, the specimen is illuminated with circularly polarized light, and the transmitted light is again analyzed for the four linear polarizations.

The polarizing splitters in the imaging path can be used to detect birefringence (anisotropy of refraction) and diattenuation (anisotropy of attenuation), which are characteristic of the molecular composition and architecture of neuronal cells. The first configuration without a polarizer in the illumination path makes the setup sensitive to diattenuation, whereas the setup is insensitive to the birefringence of the sample (Fig. 6 B). The second configuration with circular polarizer in the illumination path renders the setup sensitive to both sample properties, diattenuation and birefringence (Fig. 6 A; (31)). For the study reported here, we used both configurations to distinguish between changes in diattenuation and birefringence when analyzing the response of hippocampal slices to stimulations.

Figure 6.

Birefringence versus diattenuation as origins of polarization-sensitive IOS. (A) A schematic of the optical system with circular polarization illumination that detects both birefringence and diattenuation changes of the specimens is shown. (B) A schematic of the optical system with nonpolarizing illumination that detects diattenuation change but does not detect birefringence change of the specimens is shown. (C and D) Changes in the relative birefringence (C) and diattenuation (D) of the same hippocampal slice before and after the electrical stimulations (gray vertical lines) are shown.

We used 20× water-dipping lens (XLUMPLANFL 20×, NA 0.95; Olympus) or 4× dry lens (XL FLUOR 4×, NA 0.28; Olympus) for the instantaneous PolScope imaging. In both illumination configurations with or without circular polarizer, the transmitted light goes through an imaging path (Fig. 5 A) that projects four images onto the four quadrants of a single electron-multiplying charge-coupled device (EMCCD) camera (iXon Ultra; Andor USA, Concord, MA). Each quadrant represents the same object scene analyzed for one of the four linear polarizations (0, 45, 90, 135°). For the instantaneous PolScope analysis, the four image quadrants undergo the same computational analysis as is done for the polarized fluorescence described in (28). Briefly, for both configurations, the transmitted light intensity recorded in each quadrant is related to the average intensity across the four quadrants (I), a polarization factor p, and an azimuth orientation ϕ as follows:

| (1) |

where n = 0, 45, 90, 135°.

Figure 5.

The instantaneous PolScope. (A) A schematic drawing of the four-way linear polarization splitting system for the instantaneous analysis of polarized light through the specimen is shown. (B) Quadrant images of a mouse hippocampal slice simultaneously captured by an EM CCD camera are shown. Angles (bottom left) of each image indicate the transmission axis of the polarization analysis. An objective lens, Olympus XL FLUOR 4×, NA 0.28, was used. Scale bars, 100 μm. (C) Light intensity changes of a selected area in each quadrant image at the stratum radiatum of area CA1 (enclosed by squares in B) are plotted against time. The timing of electrical stimulation (40 Hz, 50 pulses) is indicated by a gray vertical line. (D, left) Relative birefringence image computed from four images shown in (B) is shown. (D, right) The change in the relative birefringence at the selected area (orange square shown in D) is shown. (E, left) The average transmittance image from four images shown in (B) is shown. (E, right) The change in the transmittance at the selected area (purple square shown in D) is shown. Scale bars, 100 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

Retrieval of the average intensity, orientation, and polarization factor of the light through the object is efficiently expressed in terms of the Stokes parameters of the polarization-resolved transmitted light:

with

| (2) |

| (3) |

and Ibg is the camera reading without light on the sample.

The average intensity I transmitted by the sample is

| (4) |

The above expressions are implemented as image-arithmetic operations, producing Stokes parameters, polarization factors, and orientation values for each specimen point resolved in the camera quadrants. For both configurations, i.e., with and without polarizer in the illumination path, we used the same expressions Eqs. 2, 3, and 4 for calculating the parameters p, ϕ, and I, but their physical interpretation has to change. For the configuration without polarizer, p and ϕ are directly related to the diattenuation (Imax − Imin)/(Imax + Imin) and the orientation ϕ of the linearly polarized light that is maximally transmitted. In the experiments reported in the Results, we used this configuration to ascertain that the brain tissue has no measurable diattenuation, with or without stimulation. This result was important for the interpretation of the specimen parameters measured with the second configuration setup that included a circular polarizer in the illumination path. If there is no diattenuation in the specimen, then its polarization factor can be interpreted as a measure of linear birefringence in the specimen. In that case, the polarization factor represents a differential retardation measured relative to some fixed retardance.

To quantify the temporal changes in average transmittance and relative birefringence after electrical nerve stimulations, averaged light intensities were calculated at the same selected region of interest, which were measured typically at 50–70 μm apart from the tip of the stimulating pipette. Peak amplitudes of the signals were determined by averaging together five frames around the peak for each single trial.

Statistical analyses

Data were collected by using preparations from more than three different animals. We used a software package, SigmaPlot (version 13.0; Systat, San Jose, CA) for the statistical analysis. Normality of the collected data were tested by using the Shapiro-Wilk method. To evaluate the significant difference (p < 0.001) of the data sets that had passed the normality test, we used t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey test. For evaluating the significant difference of the data sets that were rejected by the normality test, we used the Mann-Whitney test or the Kruskal-Wallis test. The Kruskal-Wallis test was followed by Dunn’s method for pairwise test of the significant difference (p < 0.05) among multiple data sets.

Results

Birefringence map of mouse hippocampal slices

We recorded images of acute slices of the mouse hippocampus using the LC-PolScope (see Materials and Methods). The raw LC-PolScope images were then further processed to compute maps of the transmittance, retardance, and orientation of the slow axis of birefringence (Fig. 1). Based on the known structural layers of the mouse hippocampus, we were able to assign intrinsic polarization parameters to layered nerve structures such as Schaffer collaterals and pyramidal and granule cell layers. Intensity profiles of each elliptical polarization illumination setting enclosed by a vertical rectangle in transmitted light image of the slice (Fig. 1 A) were plotted in Fig. 1 E. From the line profiles of the retardance values, we measured the lowest retardance value of around 3 nm at the stratum (st.) pyramidale, and the highest retardance value of around 10 nm at the st. radiatum. The image in Fig. 1 B was taken with the extinction illumination setting in which the polarization of the illumination has opposite handedness with respect to that of the circular analyzer. We found a significant difference in the brightness between the transmitted light image and that of the image obtained with the extinction illumination setting at the area in the vicinity of CA1-CA3 pyramidal cell layer and at the molecular layer (m.l in Fig. 1 A) along the granule cell layer. The retardance map (Fig. 1 C) demonstrated that the dendritic layers of area CA1 (the st. radiatum and st. oriens) were the high-birefringence areas, whereas cell body layers (the st. pyramidale and granule cell layer in Dentate gyrus (DG)) were observed as the lowest birefringence areas. There was a noticeable high-birefringence structure at the st. lacunosum-moleculare (Fig. 1, C and D, white arrowheads), which represented the axonal projection from the layer III entorhinal cortex neurons to distal dendrites of CA1 pyramidal cells known as the temporoammonic system (32). At area CA3, there was a layer with intermediate retardance values compared to the adjacent strata between the st. pyramidale and st. radiatum. This area is known as the st. lucidum, where many axons from dentate granule cells (mossy fibers) localize along proximal dendrites of CA3 pyramidal cells (33). At the st. radiatum of area CA1, slow axis orientations are perpendicular to Schaffer collateral axons and parallel to the main apical dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons (Fig. 1, D and E).

Activity-induced birefringence changes in hippocampal slices evoked by the electrical stimulation

Using the LC-PolScope, we observed a transient increase of transmittance at the st. radiatum of area CA1 after electrical stimulation (40 Hz, 50 pulses) applied at Schaffer collateral axons. The transient increase was observed for all four elliptical polarization settings (Fig. 2, extinction settings 1–4), images taken with four elliptical polarization illuminations with principle axes of 0, 45, 90, and 135° (Fig. 2; Figs. S1–S4, respectively) after nerve stimulations. These transient increases of the transmitted light intensity corresponded to the traditional IOS (8,10,12). Interestingly, in the extinction illumination setting, a transient decrease of light intensity occurred after the nerve stimulation (Fig. 2, extinction setting 0). We have not found reasonable explanations for this transient decrease of transmitted light intensity when the slices were observed with extinction illumination setting.

Figure 2.

Recording of polarization-resolved IOS changes using the LC-PolScope measured at the stratum radiatum of area CA1 followed by Schaffer collateral stimulation (40 Hz, 50 pulses). An objective lens, Olympus XL FLUOR 4×, NA 0.28, was used. Using the LC-Polscope, the images of a hippocampal slice (right) are sequentially acquired at five polarization illumination settings (setting S0–S4). The average intensities of the same area enclosed by black squares in each image are plotted against the time. Electrical stimulation is applied at t = 8 s for 1.25 s (shown as a vertical gray area). Images of S1–S4 are obtained with elliptical polarization illumination in LC-PolScope with different principle axes, 0, 45, 90, and 135°, with respect to the laboratory frame of reference. Setting 0 represents the extinction illumination condition, in which the specimen was illuminated with circularly polarized light of opposite handedness to the circular polarizer used as an analyzer. The intensities are shown as relative values by normalizing the value of setting 0 before the stimulation as 1.0.

We found that these transmittance changes of polarized light were associated with a birefringence change of the hippocampal slice. We observed the birefringence change through the sequential acquisition of five images before and after the electrical stimulation over time. Changes in the retardance value at the st. radiatum close to the tip of the stimulation electrode (enclosed by black square in Fig. 3 A) after nerve stimulation were analyzed as follows (Fig. 3 B). At the resting state, the retardance value was 13.31 ± 1.4 nm (n = 8). After Schaffer collateral stimulation, the retardance values transiently increased to 13.67 ± 1.4 nm (n = 8). The increase of retardance value at the peak was 0.2–1.0% of the resting values (paired t-test, p = 0.002). This transient retardance increase was completely diminished in the presence of 1 μM TTX, a blocker of voltage-gated sodium channels (Fig. 3 B, lower trace). The stimulation-evoked retardance increase was enhanced in the presence of 40 μM 4-aminopyridine (Fig. 3 C, lower trace), a blocker of slowly inactivating potassium channels (34). The amplitude and the duration of retardance increase were ∼2 times larger than those of the control experiment. These results indicated that the retardance change in the st. radiatum is associated with action potentials and/or the synaptic transmission after the action potential.

Figure 3.

Retardance change detected with the LC-PolScope; objective lens, Olympus XL FLUOR 4×, NA 0.28. Retardance values are measured at the stratum radiatum of area CA1 before and after the electrical stimulation of the Schaffer collateral (40 Hz, 50 pulses). (A) A representative retardance map of a hippocampal slice is shown. The black square indicates an example of an area where the retardance measurements were taken. The location of the stimulation electrode is shown as two lines. (B) Recordings of the retardance changes in normal ACSF (control, open circles) and in ACSF with 1 μM TTX (solid circles) taken at the same location of the hippocampal slice are shown. (C) Recordings of the retardance changes in normal ACSF (control, open circles) and ACSF with 40 μM 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, solid circle) from the same hippocampal slice are shown. The timings of electrical stimulations (40 Hz, 50 pulses) are shown as vertical gray areas in the graphs. Thin, solid horizontal lines in the graphs indicate the resting retardance value obtained by an average of 10 frames at the resting level before the stimulation.

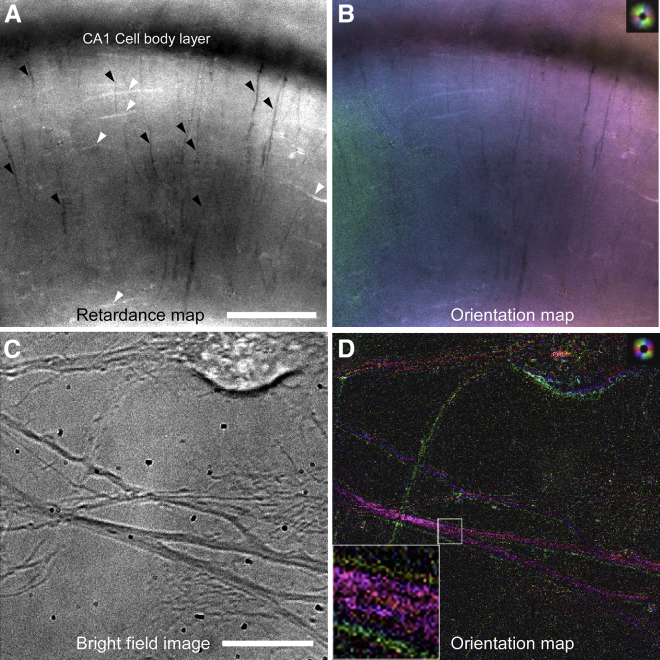

Birefringence of single neurons in slices and in primary cultures

As shown in Fig. 1, we were not able to observe the birefringence image of single neurons in hippocampal slices immersed in the normal ACSF. To obtain the retardance value and slow axis orientation of single neurons in hippocampal slice preparations, we used slices immersed in ACSF with refractive indices as high as those of the cytoplasm (35,36). We increased the refractive index of ACSF by adding iodixanol, an isoosmotic, tunable refractive index matching medium (37). We immersed the hippocampus slices in ACSF with 54% (w/v) iodixanol, with an estimated refractive index of around 1.42 (37). The ensemble slow axis orientation of the birefringence observed at area CA1 was perpendicular to the Schaffer collateral axons, as shown in the pseudocolor slow axis orientation map (Fig. 4 B). The orientation maps of hippocampus slices in ACSF with a high refractive index were consistent with those in normal ACSF (Fig. 1 D). Although the slow axis orientations were similar, the retardance maps of slices in index matching ACSF featured bright and dark thin lines or streaks pointed to by arrowheads in Fig. 4 A. Bright streaks (white arrowheads) run parallel to the Schaffer collateral axons, whereas dark streaks (black arrowheads) run parallel to the main apical dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons. The streaks have the appearance of single or bundled neuronal processes that run either parallel or perpendicular to the dense Schaffer collateral axons that generate the uniform background birefringence of the region. Processes that run parallel to the background axons are brighter, whereas those that run perpendicular to them are darker, in accordance with their positive or negative contribution to the overall birefringence measured. Based on the known anatomy of CA1 pyramidal neurons (31,38), we suggest that bright streaks correspond to particularly dense bundles of Schaffer collateral axons, whereas the more numerous dark streaks correspond to the dendrite of CA1 pyramidal cells that run perpendicular to the majority of Schaffer collateral axons.

Figure 4.

A retardance map (A) and a combination map (B) of retardance (brightness) and slow axis orientation (color) of mouse hippocampus slice immersed in ACSF with 54% (w/v) of iodixanol. An bjective lens, Olympus XLUMPLANFL 20×, NA 0.95, was used. Scale bars, 100 μm. In (A), white arrowheads indicate bright streaks running parallel to the stratum radiatum, and black arrowheads indicate dark streaks running perpendicular to the stratum radiatum. Scale bars, 100 μm. The color wheel in (B) on the top right shows the reference for the local slow axis orientation of birefringence. (C) Transmitted light and (D) LC-PolScope image of primary cultured hippocampal neurons show a cell body (right top) and neurites. An objective lens, PlanApo VC 60×, NA 1.4 (Nikon), was used. Scale bars, 10 μm. In (D), the color (hue) indicates the slow axis orientation, and the brightness indicates the retardance value. An area enclosed by a white square in (D) is magnified as an inset at the left-bottom corner. The color wheel on the top right shows the reference for the local slow axis orientation of birefringence. To see this figure in color, go online.

We also analyzed polarized light images of the principal neurons of the hippocampus in primary neuronal cultures. For these observations, we used a 60× 1.4 NA oil immersion lens (PlanApo VC; Nikon) that allows subcellular birefringence mapping of principal neurons (Fig. 4, C and D). The slow axis orientation map of single neurons revealed that there were two different birefringent components in the dendritic structure, which were observed in the cytoplasm and near the surface of the dendritic shafts. The birefringence in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4 D, magenta) had slow axis orientations parallel to the longitudinal axis of the dendrite. The retardance value of the cytoplasmic structures inside the dendrite was 1.04 ± 0.10 nm (n = 8). The cytoplasmic birefringent component was surrounded by another birefringent component along the surface of the dendrite (Fig. 4 D, blue-green). This sheathe-like birefringent component had its slow axis orientation perpendicular to the length of the dendrite and a retardance value of 0.51 ± 0.03 nm (n = 8). These observations were consistent with previous observations of birefringent structures in the neurites of Aplysia bag cell neurons using the LC-PolScope (26,39).

Instantaneous PolScope imaging to study the mechanisms of activity-induced birefringence changes in mouse hippocampal slices

In our LC-PolScope imaging, changes in birefringence that occur in the specimen during the acquisition of the five raw intensity images generate spurious effects in the subsequently calculated retardance and orientation maps. Because the LC-PolScope sequentially acquires five images of different polarization illumination settings, a rapidly changing optic axis orientation, for example, causes unavoidable artifacts in the calculated retardance and slow axis orientation maps. To avoid these artifacts and to achieve high temporal resolution to examine the activity-induced birefringence changes in mouse hippocampal slices, we developed the instantaneous PolScope, which is a modified version of our instantaneous FluoPolScope that we developed for tracking the position and orientation of single fluorophores in living cells (28). Hippocampal slices were illuminated with circularly polarized light, and the instantaneous polarization analysis was done by recollimating the light originating from the primary image plane of the microscope. In the collimated space, the light is first divided equally between two arms by a polarization independent beam splitter (50:50 mirror in Fig. 5 A). This is followed by a polarizing beam splitter in each arm, separating the light into a total of four beam paths and analyzing their linear polarization along 0, 45, 90, and 135° orientations. One polarizing splitter generates 0 and 90° polarization beam paths, whereas the polarization in the other arm was first rotated by 45° using a half-wave plate (1/2 λ plate in Fig. 5 A) and then passed through the other polarizing splitter to generate the 45 and 135° paths. Subsequently, we use broadband mirror-based beam-steering optics and a focusing lens to project four images onto the four quadrants of a single EMCCD detector (Fig. 5 B). Projected images of hippocampal slices revealed changes in light intensity in all four polarization orientations (I0°, I45°, I90°, I135°) after stimulation (Fig. 5 C). From the acquired images, we computed the polarization factor p, hereafter, referred to as “relative birefringence” (Fig. 5 D). The transmittance of all quadrant images before and after the electrical stimulation was averaged and normalized with respect to the value before the stimulation. Hereafter, the value will be referred to as “relative transmittance” (Fig. 5 E). Thus, by using the instantaneous PolScope imaging, we could generate maps of temporal changes in the relative birefringence maps that correspond to the retardance maps obtained with the LC-PolScope but with high time resolution. The time resolution of this system was set by the acquisition rate of the camera and was ∼100 Hz for our EMCCD camera (iXon Ultra; Andor). Compared to the LC-PolScope, the instantaneous PolScope improved the time resolution by a factor of 100.

Birefringence versus diattenuation of hippocampal slices observed with the instantaneous PolScope

The polarization-sensitive IOS (pol-IOS) of hippocampal slices can be caused by changes in the specimen’s birefringence, i.e., polarization-dependent differences in refractive index, or diattenuation, which are polarization-dependent differences in transmittance. We examined both contributions, birefringence and diattenuation, to the polarization-sensitive IOS in response to nerve stimulations (31). To test these two polarization-sensitive optical properties, we illuminated the hippocampal slice with two different illumination conditions: 1) circularly polarized illumination (Fig. 6 A) and 2) unpolarized illumination (Fig. 6 B). When using unpolarized illumination, the setup is insensitive to birefringence, and any measured polarization effect is only due to diattenuation (see Materials and Methods). When using circularly polarized illumination, however, the setup is sensitive to both properties, birefringence and diattenuation. Therefore, we first ascertained that the signal changes in stimulation-evoked pol-IOS were only detected when the brain slice was illuminated with circularly polarized light (Fig. 6 C) but not with unpolarized illumination (Fig. 6 D). This result clearly indicated that the pol-IOS change at area CA1 originated predominantly from transient changes of birefringence and not from changes in diattenuation.

Time-resolved mapping of stimulation-evoked birefringence changes at CA1 of hippocampal slices

The spatial distribution of relative birefringence changes was observed at the st. radiatum of area CA1 after Schaffer collateral stimulation. To observe a larger field of view, we used a low magnification objective lens (XL FLUOR 4×, NA = 0.28; Olympus) (Fig. 7, A and C). To enhance the changes, intensities of both transmittance (IOS) and birefringence (pol-IOS) images at each frame were subtracted by the images of their resting state before the stimulation (Fig. 7, B and D). After electrical stimulation, transmittance changes were observed along the st. radiatum (Fig. 7 B). This result was consistent with the IOS imaging of hippocampal slices reported by others (8,12,17,40). We observed birefringence changes near the site of electrical stimulation (Fig. 7 D). Birefringence changes were observed along the st. radiatum toward both the CA3 and subiculum directions, but not in other strata such as the st. oriens and the st. lacunosum-moleculare. Interestingly, around 60 s after the stimulation when the birefringence diminished at the st. radiatum, a weak increase in birefringence was observed at the st. pyramidale, where the cell bodies of CA1 pyramidal neurons are located. We speculate this delayed birefringence increase might originate from anisotropic changes of extracellular structures that surround the cell body of CA1 pyramidal neurons.

Figure 7.

Imaging of traditional IOS and polarization-sensitive IOS at the stratum radiatum of area CA1 by using the instantaneous PolScope. (A) An average transmittance image of the hippocampal slice is shown. A glass pipette for electrical stimulation is seen at the top left of the image. (B) Time-dependent change of the traditional IOS image of area CA1 can be observed in the area enclosed by the broken white rectangle in (A). Numbers shown at the right bottom show the time after the electrical stimulation applied at t = 0 s (40 Hz, 50 pulses). (C) A relative birefringence image of the hippocampal slice is shown. (D) Time-dependent change of polarization-sensitive IOS image can be observed in the area enclosed by the broken white rectangle in (C). To enhance the stimulation-evoked changes of the images in (B) and (D), the averaged images before the stimulation were subtracted from all the frames. An objective lens, Olympus XL FLUOR 4×, NA 0.28, was used. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Local difference of stimulation-evoked birefringence changes at stratum radiatum of area CA1

Through the correlative observations of pol-IOS and traditional IOS, we explored the structures at the st. radiatum of area CA1 in which the activity-induced birefringence changes were largest. Using the instantaneous PolScope, we generated maps of transmittance and of relative birefringence (Fig. 8) in fast time intervals before and after the Schaffer collateral stimulation. Based on birefringence values at the resting state, we created two segmented zones: one with a high resting birefringence and another with a low resting birefringence (green and blue areas, respectively). When comparing the time courses of birefringence changes in these two areas after stimulation, we found significant differences in their stimulation-evoked birefringence responses (Fig. 8 E), which correlated with the local difference of the static (resting) birefringence. The pol-IOSs in areas of high resting birefringence (blue areas in Fig. 8 C) were ∼2.7 times larger than those observed in low-birefringence areas (green areas in Fig. 8 C). Interestingly, there were similar local differences in the traditional IOS (Fig. 8 D), but the differences were smaller (1.1-fold difference) than those observed for pol-IOS changes. Thus, we found that 1) there were local differences between IOSs observed in areas with low birefringence and high birefringence; 2) for both birefringence and transmittance, IOSs observed in high-birefringence areas were larger than those observed in low-birefringence areas; and 3) these local differences were more pronounced for birefringence signals than for transmittance signals. These findings indicate that the local difference of pol-IOS is correlated with the birefringent cellular architectures in the brain.

Figure 8.

Local difference of polarization-sensitive IOS at the stratum radiatum of area CA1. (A) Average transmittance map is shown. An objective lens, Olympus XLUMPLANFL 20×, NA 0.95, was used. Scale bars, 10 μm. (B) Relative birefringence map of the same area in (A) is shown. (C) Segmentation of high birefringence area exhibiting top 10% (green) and low birefringence area exhibiting bottom 10% (blue) of the brightness distribution at areas shown in (B) is shown. (D and E) The average transmittance change (D) and relative birefringence change (E) observed at high birefringence regions (green) and low birefringence regions (blue) are plotted against time, respectively. Electrical stimulation (40 Hz, 50 pulses) was applied during the time shown as gray vertical areas. Values (relative change) in (D) and (E) are normalized so that the average values before the simulations are 1.0. To see this figure in color, go online.

Correlation between the number of stimulation pulses and the amplitudes of pol-IOS and traditional IOS

We tested the correlation between the strength of stimulation and the amplitudes of pol-IOS and traditional IOS by modulating the number of stimulation pulses (amplitude 250 μA; duration 1 ms, interval 25 ms, which corresponds to a rate of 40 Hz) to the Schaffer collaterals. We measured changes in the relative birefringence and transmittance in a selected square area (∼800 μm2) in the st. radiatum before and after the stimulations (Fig. 9). Even a single pulse elicited small but detectable IOS changes in both birefringence and transmittance. These IOS changes increased as the number of stimulation pulses increased and reached their saturation levels at 50 pulses (Fig. 9, A and B). The stimulation-response curve of relative birefringence change and transmittance change were similar (Fig. 9 C). Based on these results, we used 50 pulses as standard electrical stimulation hereafter to induce excitation of Schaffer collateral axons and the following synaptic transmission. The evoked birefringence and transmittance signals were easily reproducible in peak amplitude, rise time, and decay time.

Figure 9.

Relationship between the number of stimulation pulses and the IOSs changes. (A) Superimposed traces of relative birefringence changes elicited by various numbers of pulses (1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 50, and 100) with 1.25 ms intervals (40 Hz) are shown. (B) Superimposed traces of relative transmittance changes elicited by various numbers of pulses (1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20, 50, and 100) with 1.25 ms intervals (40 Hz) are shown. (C) The peak values of relative transmittance (open circles) and relative birefringence (solid circles) were plotted against the applied numbers of pulses. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6).

Distinct decay time courses of temporal changes in birefringence and transmittance signals

By repeatedly applying the same number of pulses (41) to the same area of the stratum radiatum of area CA1, we have established the consistency of temporal changes in relative birefringence and transmittance induced by electrical stimulation. Fig. 10 shows representative relative birefringence and transmittance signals obtained from the same data sets. The rise times (from 20 to 80% of the peak value) of relative birefringence and transmittance were 1.44 ± 0.13 and 1.21 ± 0.064 s, respectively, indicating no significant difference between these two IOSs (Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.77, n = 30). The characteristic decay times τ of the relative birefringence and transmittance were evaluated by fitting a single exponential to the time course of decay from 80 to 20% of the peak amplitude. The time constant for the birefringence decay in Fig. 10 A was 29.6 s, whereas it was 48.3 s for the transmittance decay (Fig. 10 B). There was a variation in the peak amplitude of birefringence among brain slices, possibly due to variations in thickness and/or tilt of neuronal cell alignments with respect to the plane of the slices. We found no correlation between the peak amplitude of birefringence and its decay time constant in each individual trace (data not shown). For most of the pairs (25 out of 28 traces) of transmittance and birefringence data sets, the decay time constant of birefringence was faster than that of transmittance (Fig. 10 C). The paired plots of decay time constants of birefringence and transmittance signals were fitted by a regression line with a slope of 1.83. Averaged values of the time constant were 30.3 ± 2.3 s for birefringence and 55.5 ± 7.1 s for transmittance, indicating a significant difference in the decay times (Fig. 10 D) (Mann-Whitney test, p < 0.001, n = 28).

Figure 10.

Decay time analysis of IOSs. (A) Relative birefringence change measured at stratum radiatum of area CA1 (black dots) is shown. Decay time constant was estimated by fitting the decay phase of relative birefringence with single exponential function. (B) Relative transmittance changes are shown. Both relative birefringence and transmittance were computed using the same raw image data recorded with the instantaneous PolScope. (C) Decay time constants of the polarization-sensitive IOS (relative birefringence (Bi)) and the traditional IOS (average transmittance (Tr)) are shown. The decay time constant was estimated by fitting the decay phase of relative Bi and relative Tr with a single exponential function. There is a positive correlation between decay time constant of Bi and Tr (the slope of the regression line is 1.83, r = 0.6, p < 0.001, n = 28, linear regression analysis). (D) Averaged decay time constant of relative Bi and average Tr is shown. The time constants for relative Bi was 30.3 ± 2.35 s (open bar) and 55.5 ± 7.09 s for relative Tr (gray bar). Data are shown in mean ± SEM. A significant difference is found between Bi and Tr (the asterisk denotes the Mann-Whitney test, p < 0.001, n = 28).

Glutamate as a key molecule for generating activity-induced birefringence changes in hippocampal slices

We observed birefringence changes at the st. radiatum, st. orience, and st. lacunosum-moleculare in area CA1 followed by electrical stimulation. These strata include many synaptic inputs from axons that make synapses between apical and basal dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons. In particular, the st. radiatum is known to have dendritic alignments lining radially from the st. pyramidale (42), receiving many excitatory synaptic inputs from axons of CA3 pyramidal neurons that release glutamate as a neurotransmitter.

To address whether an external glutamate application alone can elicit a birefringence change, a small amount of 10 mM glutamate in ACSF was locally applied to the st. radiatum through a glass micropipette (Fig. 11). A transient increase of birefringence was observed after puff application of glutamate for 1 s. This glutamate-evoked transient increase in birefringence was not affected by adding 1 μM TTX in ACSF, indicating that postsynaptic activity alone can generate transient birefringence changes at the st. radiatum in the hippocampal slice.

Figure 11.

Generation of pol-IOS by external glutamate application to hippocampal slice both in the presence and absence of TTX. A pulse application of 10 mM glutamate through a glass pipette for 1 s duration (indicated by gray area) caused relative birefringence changes in both the presence (solid circle) and absence (open circle) of 1 μM tetrodotoxin.

To further address the mechanisms underlying the generation of stimulation-evoked birefringence changes in hippocampal slices, we examined the involvement of excitatory synaptic transmission using pharmacological approaches. First, we tested for ionotropic glutamate receptors. Both AMPA-type and NMDA-type glutamate receptors are abundantly expressed at spines and dendrites of pyramidal neurons, which are known to play a major role in excitatory synaptic transmission and plasticity in the hippocampus (43,44). 10 μM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), a potent and selective blocker of AMPA-type glutamate receptors, decreased the amplitude of relative birefringence (Fig. 12 A, CNQX), compared with that of the control condition (Fig. 12 A, control). Coapplication of 50 μM D-APV, a selective blocker of NMDA-type glutamate receptor, with 10 μM CNQX significantly suppressed the amplitude of relative birefringence after the electrical stimulation (Fig. 12 A, CNQX + D-APV). The peak amplitudes were reduced to 2.65 ± 0.34 in the presence of CNQX, and 1.28 ± 0.18 in the presence of both CNQX and D-APV (ANOVA p < 0.001, n = 7, Fig. 12 B) compared to the control value of 3.98 ± 0.57. The decay time constant became shorter: from 29.6 ± 3.90 s in the control condition to 25.3 ± 2.77 s in the presence of 10 μM CNQX and 14.2 ± 1.71 s in the presence of both 10 μM CNQX and 50 μM D-APV (ANOVA, p = 0.018, n = 7, Fig. 12 C). We observed similar results in the relative transmittance changes (Fig. 12 D). In the presence of 10 μM CNQX, the peak amplitude was decreased from 6.69 ± 0.78 (control) to 5.23 ± 0.48 and was further decreased to 1.92 ± 0.38 in the presence of 10 μM CNQX and 50 μM D-APV (ANOVA, p = 0.003, Fig. 12 E). The decay time constant became shorter: from 69.6 ± 15.8 s in the control condition to 51.1 ± 8.45 s in the presence of CNQX and 27.6 ± 3.30 s in the presence of both CNQX and D-APV (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA rank, p = 0.005, n = 7, Fig. 12 F). These data indicate that 67 and 71% of the amplitudes of birefringence and transmittance signals, respectively, were suppressed by the coapplication of CNQX and D-APV. Our results indicate that birefringence and transmittance signals induced by electrical stimulation were generated predominantly through the mechanisms that involved these postsynaptic glutamate receptors in CA1 neuronal dendrites. The results also indicate that ∼30% of the optical signals are originating from mechanisms that are unrelated to ionotropic glutamate receptors.

Figure 12.

Effects of ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists on activity-induced relative birefringence and transmittance changes at the stratum radiatum of area CA1. (A) A series of recordings of relative birefringence changes induced by electrical stimulation in ACSF (control, open circle), with 10 μM CNQX (CNQX, gray circle), and with 10 μM CNQX and 50 μM D-APV (CNQX + APV, solid circle) are shown. In the inset, normalized three traces of birefringence changes (control, CNQX, CNQX + APV) by adjusting the height from the baseline to the peak of each trace as 1 are shown. (B) Summary of the effects of CNQX and D-APV on the peak amplitude of relative birefringence changes is shown. The peak value is expressed as increase in percentage from the resting birefringence value. 3.98 ± 0.57% (control, white bar), 2.65 ± 0.34% (CNQX, gray bar) and 1.28 ± 0.18% (CNQX + APV, black bar) are portrayed in the histogram. Significant change is found between control and CNQX + APV (p < 0.001, n = 7) and one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise multiple comparison procedures (post hoc Tukey test). (C) A summary of the effects of CNQX and D-APV on decay time constant of relative birefringence changes is shown. The decay time constant is estimated by fitting the decay phase of relative birefringence with a single exponential function. 29.6 ± 3.90 s (control, white bar), 25.3 ± 2.77 s (CNQX, gray bar) and 14.2 ± 1.71 s (CNQX + APV, black bar) are portrayed in the histogram. Significant change is found between control and CNQX + APV (p = 0.018, n = 7) using one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise multiple comparison (post hoc Tukey test). (D) A series of recordings of relative transmittance changes induced by electrical stimulation in normal ACSF (control, open circle) with 10 μM CNQX (CNQX, gray circle) and with 10 μM CNQX and 50 μM D-APV (CNQX + APV, solid circle) is shown. In the inset, normalized three traces of transmittance changes (control, CNQX, CNQX + APV) by adjusting the height from the baseline to the peak of each trace as 1. (E) A summary of the effects of CNQX and D-APV on the peak amplitude of relative transmittance change is shown. The peak value is expressed as increase in percentage from the resting transmittance value. 6.69 ± 0.78% (control, white bar), 5.23 ± 0.48% (CNQX, gray bar), and 1.92 ± 0.38% (CNQX + APV, black bar) are portrayed in the histogram. Significant changes are found between the control and CNQX + APV (p < 0.001, n = 7) as well as CNQX and CNQX + APV (p = 0.003, n = 7) using one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise multiple comparison procedures (post hoc Tukey test). (F) A summary of the effects of CNQX and D-APV on the decay time constant of relative transmittance change is shown. 69.6 ± 15.8 s (control, white bar), 51.1 ± 8.45 s (CNQX, gray bar) and 27.6 ± 3.30 s (CNQX + APV, black bar) are portrayed by the histogram. A significant change is found between control and CNQX + APV (p = 0.005, n = 7) using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on Ranks followed by pairwise multiple comparison procedures (Dunn’s method). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05.

To further explore the involvement of glutamate for the generation of birefringence in the hippocampal slice, we tested the effects of blockers of glutamate transporters in neurons and glial cells. Rapid clearance of glutamate from the synaptic cleft is critical for preventing excitotoxicity and for maintaining the reliability of excitatory synaptic transmission. Inhibiting the rapid clearance of glutamate from the synaptic cleft by the blockers may induce larger and prolonged optical signals if glutamate is the trigger for the optical signals after electrical stimulation. Glutamate uptake is mediated by glutamate transporters located at plasma membranes of neurons and astrocytes (45). There are three types of glutamate transporters, GLAST, GLT-1, and EAAC1 (rodent analogs of the human transporters EAAT1, 2, and 3, respectively), that are known to be present in the mature hippocampus. GLT-1 and GLAST are expressed predominantly in plasma membranes of astrocytes. GLT-1 is known to play a major role in cleaning extracellular glutamate near excitatory synapses (46). It is reported that GLT-1 is also detected in axon terminals of CA3 pyramidal cells in the hippocampus and is taking up extracellular glutamate into nerve terminals (47,48). EAAC1 is a neuron-specific glutamate transporter that is abundantly expressed at postsynaptic densities (46,49), dendritic shafts, and spines surrounding active zones of excitatory synapses in CA1 pyramidal neurons (50). We used two different inhibitors of glutamate transporters to address the contribution of glutamate to the generation of birefringence changes in hippocampal slices accompanied by neuronal activation. Dihydrokainate (DHK) is a selective blocker of the glial glutamate transporter GLT-1 (41). DL-TBOA blocks both neuronal and glial glutamate transporters GLT-1 (EAAT2) and EAAC1 (EAAT3) at lower concentrations than blocking GLAST (EAAT1) (IC50-values are 70, 6, and 6 μM for EAAT1, EAAT2, and EAAT3, respectively) (38). We applied 50 μM DL-TBOA or 300 μM DHK to hippocampal slices and compared the optical signals after electrical stimulations. The birefringence change was dramatically enhanced by DL-TBOA (Fig. 13 A), whereas DHK had little effect (Fig. 13 B). The average increase of peak amplitude (in percentages) from the resting values analyzed from pooled data demonstrated that the amplitude of birefringence signal increased from 6.74 ± 2.10 (control) to 13.12 ± 3.76 (DL-TBOA) (Fig. 13 C, paired t-test, p = 0.036, n = 5). In contrast, DHK induced no significant change (Fig. 13 D, 8.42 ± 2.66 in control, 7.88 ± 2.54 in DHK, paired t-test, p = 0.36, n = 5).

Figure 13.

Effects of inhibitors of glutamate transporters on activity-induced relative birefringence and transmittance changes at the stratum radiatum of area CA1. (A) Representative recordings of relative birefringence changes elicited by electrical stimulation before (control, open circle) and after the application of 50 μM DL-TBOA (TBOA; solid circle) are shown. (B) Recordings of stimulation-evoked relative birefringence changes before (control, open circle) and after the application of 300 μM dihydrokainate (DHK solid circle) are shown. (C) Summary of the effect of TBOA on the peak amplitude of relative birefringence changes. The peak value is expressed as increase in percentage from the resting birefringence value. 6.74 ± 2.10% (control, white bar), 13.12 ± 3.76% (TBOA, gray bar). Paired t-test, p = 0.036 (n = 5). (D) Summary of the effect of DHK on the peak amplitude of relative birefringence changes. 8.42 ± 2.66% (control; white bar) and 7.88 ± 2.54% (DHK, gray bar) are shown in the histogram. Paired t-test, p = 0.36 (n = 5). (E) Recordings of stimulation-evoked relative transmittance changes before (control, open circle) and after the application of 50 μM DL-TBOA (TBOA, solid circle) are shown. (F) Recordings of stimulation-evoked relative transmittance changes before (control, open circle) and after the application of 300 μM DHK (solid circle) are shown. (G) A summary of the effect of TBOA on the peak amplitude of relative transmittance changes is shown. The peak value is expressed as an increase in percentage from the resting transmittance value. 6.20 ± 0.54% (control; white bar) and 8.74 ± 1.02% (TBOA; gray bar) are shown in the histogram. Paired t-test, p = 0.010 (n = 5). (H) A summary of the effect of DHK on the peak amplitude of relative transmittance changes is shown. 6.52 ± 0.38% (control; white bar) and 6.40 ± 0.41% (DHK; gray bar) are shown in the histogram. Paired t-test, p = 0.781 (n = 5). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ∗p < 0.05.

Next, we analyzed the effect of DL-TBOA (Fig. 13 E) and DHK (Fig. 13 F) on the transmittance signal. Similar to the result in the birefringence signal, generation of average transmittance was significantly enhanced by DL-TBOA (Fig. 13 G, 6.20 ± 0.54 in control, 8.74 ± 1.02 in DL-TBOA, paired t-test, p = 0.01, n = 5), but not by DHK (Fig. 13 H, 6.52 ± 0.38 in control and 6.40 ± 0.41 in DHK, paired t-test, p = 0.78, n = 7). Our results suggest that the synaptic glutamate release that is cleaned up by EAAC1 and/or GLT-1 triggers the generation of optical signals. GLT-1 and EAAC1 show more enriched immunoreactivities than that of GLAST in the mature hippocampus (51,52). Given that more than 80% of total glutamate is taken up by GLT-1 and EAAC1 in the hippocampus (40% with GLT-1 and 40% with EAAC1) (53,54), the contribution of GLAST is estimated to be less than 20% of the total glutamate uptake in the mature hippocampus.

Discussion

Polarized light imaging as a label-free method for observing neuronal structures and their activity-induced changes in the brain

IOS imaging has been widely used to map patterns of brain activity in a label-free manner. Because of its reliable spatiotemporal features, IOS has been utilized for monitoring both physiological and pathological brain functions (8, 9, 10,12,55). For example, it was successfully used to identify functional columns in the brain, which are patterns of local brain activity induced by sensory stimulation in vivo, such as the visual and somatosensory cortex (1), olfactory bulb (56), and barrel cortex (57). These IOS changes in intact brains are primarily attributed to changes in hemodynamics and blood flow. In isolated ex vivo brain slices, the effects of hemodynamics and blood flow are not involved in IOSs, which, in the absence of blood flow, are mostly attributed to cell swelling and extracellular volume changes in the tissue (8,9,12,40). Despite the utility for monitoring brain activity in a label-free manner, traditional IOS does not yet make use of polarization-dependent changes in light reflectivity, transmission, and birefringence of cells and tissues. Therefore, we explored the use of polarized light imaging as a plausible label-free approach to include activity-induced cellular and molecular changes.

The major finding by using polarized light imaging is that activity-induced IOS changes in the isolated brain involve anisotropic structural changes presumably originating from dendrites. These changes were predominantly detected at locations that exhibited a high resting birefringence in the hippocampal slice (Fig. 8 E). The local difference of stimulation-evoked optical responses was not clearly observed with traditional IOS (i.e., transmittance) imaging (Fig. 8 D). Thus, the polarization-sensitive IOS (i.e., birefringence) reports structure-related changes in the dendritic regions that are not clearly detected with the traditional IOS. Our results indicate that polarized light imaging can add structural insights into the mechanisms underlying activity-induced IOS generation (8,9,12,17,40). The time resolution of our instantaneous PolScope was set by the acquisition rate of the camera and was ∼100 Hz for our EM CCD camera (iXon Ultra; Andor). By using a camera with a kilohertz acquisition rate, we might be able to apply our imaging to map the activity of channels in CA1 pyramidal neurons (58) and in cortical pyramidal neurons (59) as local birefringence changes.

We understand that our current instantaneous PolScope imaging does not provide enough spatial resolution to resolve single cells, which made it difficult to identify the cellular and subcellular structures that are responsible for the high or low birefringence. We have shown that the application of nontoxic, isoosmotic refractive-index-matching media (Fig. 4 A) improved the spatial resolution of the instantaneous PolScope. We hope that further preparative improvements will allow the identification of subcellular structures that generate birefringence changes after electrical stimulations.

Mapping resting birefringence and its structural sources in acute mouse hippocampal slices

We recorded birefringence maps of acute hippocampal slices using the LC-PolScope (24,60). These maps showed that the optical properties of birefringence (slow axis orientation and retardance value) were correlated with the density of neuronal processes and their orientation in the hippocampal slice (Fig. 1). Based on the anatomy of the hippocampus, Schaffer collateral pathways (axons of CA3 neurons) are aligned perpendicular to the primary dendrites of CA1 neurons at the st. radiatum (42,61). In this area, the slow axis orientation was mostly perpendicular to the net orientation of Schaffer collateral pathways (Fig. 1 D). The LC-PolScope detects retardance values below 1 nm; therefore, it enables the detection of weak birefringence of single-nonmyelinated axons and dendrites in mammalian brains (27) after uneven refractive indices in the brain tissue are effectively suppressed by the appropriate index-matching solutions. We used iodixanol as a nontoxic, isoosmotic refractive-index-matching medium for live specimens (37). In hippocampal slices immersed in ACSF with 54% (w/v) of iodixanol, we observed the birefringence of single dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons. The slow axis orientation was orthogonal to the length of the dendrites (Fig. 4, A and B, black arrowheads). Although the net slow axis orientation in area CA1 is parallel to the majority of dendrites (Figs. 1 D and 4 B), the dark images of dendrites in the retardance map indicated the destructive contribution of dendritic birefringence to the background birefringence, presumably originating from the bundle of Schaffer collateral axons. In contrast to the dark streak images of dendrites, we could not identify birefringence images of single Schaffer collateral axons in the area CA1, although we observed some bright and thick streaks running parallel to stratum radiatum (Fig. 4 A, white arrowheads). Difficulty in observing single Schaffer collateral axons might come from a high density of axons that are too tightly packed to be resolved with our imaging system.

Now, what might be the source of static birefringence in terms of cellular and molecular structure observed in the hippocampal slice? To answer this question, we observed primary cultured neurons with the LC-PolScope equipped with a high-power, high-NA objective lens (60× NA 1.4). We found two different components of birefringence in individual dendrites (Fig. 4 D) of primary cultured hippocampus neurons. The first component was observed in the cytoplasmic region of dendrites, whose slow axis orientation was analyzed as parallel to the longitudinal axis of the dendrites. Cytoskeletal proteins are abundant in the cytoplasm of dendrites, especially microtubules, which tend to be aligned parallel to the dendritic axis. The slow axis orientation of bundles of microtubules is parallel to the long axis of the filaments (25,62,63). Therefore, current and past observations suggest that microtubules are one of the major contributors to the birefringence signal from the cytoplasm of dendrites. A second birefringence component was observed at the surface of dendrites, in which the slow axis was perpendicular to the long axis of the dendrites. The cell membrane enclosing the dendritic tube could be a source of this birefringent layer because previous studies by others have shown that the birefringences of lipid membranes have slow axes that are typically normal to the plane of the membranes (64, 65, 66, 67, 68). Another source of this birefringent layer at the surface of dendrites might be edge birefringence (69), which is typically observed at the interface between two media of different refractive indices.

Our result revealed that the absolute retardance value of the cytoplasmic component was twice as high as that of the surface component (see Results). Thus, we consider the net birefringence and its slow axis orientation of single dendrites to be parallel to the dendritic axis. In contrast to the observations of primary cultured neurons, polarized light imaging of neurons in the brain tissue has revealed that the slow axis orientations of neuronal processes are always perpendicular to the processes. In our previous study using acute cerebellar slices (27), the slow axis orientations of parallel fibers, which are bundles of nonmyelinated axons, were perpendicular to the longitudinal axis, and the slow axis orientations of the myelinated axons at white matter of cerebellum were also perpendicular to their length (27). Thus, in our observations of neurons in slice preparations, both myelinated and nonmyelinated axons and dendrites show slow axis orientations that are perpendicular to the length of the neuronal processes. In addition to our observations, the slow axis of birefringence in nonmyelinated axon bundles of freshwater pikes was perpendicular to the fibers (65,70). For reasons that are still mysterious, these observations have shown that in neuronal tissues, nerve processes show slow axis orientations perpendicular to the axes of the processes, irrespective of their myelination.

Our basic understanding of the origins of resting birefringence in neuronal processes is generally consistent with reports by others (64,65,70, 71, 72). The resting birefringence of neuronal tissue can be preserved even after their chemical fixation, as long as both the cytoplasmic and the lipid membrane components are well preserved (71). Polarized light imaging can now be applied to map the three-dimensional wiring of fiber tracts of brain preparations from humans and primates without staining the tissue (73, 74, 75).

Origins of activity-induced birefringence changes in mouse hippocampal slices

The instantaneous PolScope enabled us to detect changes of polarization-sensitive IOS (relative birefringence) at area CA1 of the hippocampus after electrical stimulation at Schaffer collaterals. The spatial and the temporal changes of the pol-IOS were similar to those observed with traditional IOS (average transmittance), except that the decay time of the relative birefringence was faster than that of the transmittance (Fig. 10). Our results using blockers of AMPA-type and NMDA-type glutamate receptors indicated that ∼70% of activity-induced birefringence changes were due to mechanisms that involve ionotropic glutamate receptors and/or subsequent responses in postsynaptic neurons. This fact is similar to previous reports using traditional IOS imaging (8,12). These observations suggest that the mechanisms of activity-induced birefringence changes could be involved in the mechanisms invoking traditional IOSs. MacVicar et al. (8) proposed that a major cause of synaptically evoked IOS is the swelling of postsynaptic neurons, which is due to the water influx through the membrane (8,9,40). We found that the local difference of stimulation-evoked pol-IOS was not clearly observed in the transmittance changes. This result indicates that mechanisms that are not involved in traditional IOS might be in the generation of pol-IOS, which might be related to birefringent structures in neuronal cells.

The hypothesis found in the literature invokes mechanisms that relate the anisotropic polarizability of phospholipids (76) and aligned sodium channel peptide bonds (77,78) to birefringence changes that are associated with fast action potentials. For the postsynaptic origins of activity-induced birefringence changes, one possible cause is the reorganization of the cytoskeleton that is associated with synaptic inputs. Reorganization of postsynaptic structures includes modifications of spines in their shape, volume, and number, as reported by others (79,80). Fluorescence resonance energy transfer imaging demonstrated that the tetanic stimulation to Schaffer collateral enhanced actin polymerization in the spine head (81). Because aligned actin filaments generate birefringence signals (26,39), changes in F-actin architectures could contribute to overall birefringence changes in the dendritic area at CA1 after synaptic transmission.

Our pharmacological data suggest that the birefringence signal involves several processes, predominantly (∼70%) the activation of AMPA and NMDA receptors (Fig. 12). Previous studies indicate that excitatory synaptic transmission alters postsynaptic organization of actin filaments via AMPA and NMDA receptor activation (82,83). These studies support the idea that architectural changes of actin filaments in spines and dendrites through activation of postsynaptic AMPA and/or NMDA receptors can be one of the sources of birefringence change.

We expected the concentrations of CNQX (10 μM) and D-APV (50 μM) to be sufficient to block the activity of ionotropic glutamate receptors. However, the application of CNQX and D-APV with those concentrations failed to show the complete inhibition of IOSs. These results suggested that there are other origins of IOSs that are unrelated to postsynaptic ionotropic glutamate receptors. The remaining 30% of the stimulation-evoked birefringence change could have presynaptic origins and/or glial cell origins. For presynaptic origins for birefringence changes, membrane dynamics at presynaptic terminals can be involved, particularly vesicular endocytosis followed by excitatory synaptic transmission. Salzberg and his colleagues (20) have shown nanometer-scale movement of nerve terminals that are associated with the large change in light scattering that accompanies the secretion from nerve terminals of the mammalian neurohypophysis (19). These findings suggested the involvement of membrane vesicle dynamics at synapses in the changes of optical properties invoked by neuronal activity. A recent study demonstrated the time required for clathrin-mediated vesicular endocytosis recorded at presynaptic terminals after repetitive action potentials was ∼26 s (84). Our data showed that the decay time constant of birefringence changes was 30.3 ± 2.35 s (Fig. 10), which is close to the time constant for the internalization of synaptic vesicles. Similarity in these time courses implies some relation between the presynaptic membrane dynamics and activity-induced birefringence changes. Change in the number of synaptic vesicles may affect the net birefringence of membranous organelles, including tubular or button-shaped membranes in synapses.

Conclusions

We examined static birefringence patterns and their stimulation-evoked changes in acute mouse hippocampal slices. The hippocampal maps of retardance and slow axis orientation were recorded using the LC-PolScope. We observed static birefringence in the dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons, in which the slow axis orientations were perpendicular to the length of the dendrites. With the help of the instantaneous PolScope, we addressed questions regarding the mechanisms underlying activity-induced polarization-sensitive IOS (relative birefringence). The local application of glutamate to the stratum radiatum induced increases in both relative birefringence and transmittance. Pharmacological experiments indicated that ∼70% of the activity-induced birefringence change was related to ionotropic glutamate receptors and/or subsequent responses at postsynaptic neurons. Upon neuronal stimulation, changes in transmittance were broadly similar across the area, whereas birefringence imaging revealed local variations not seen in transmittance changes. Locations with high birefringence produced larger signal changes than those with low-resting birefringence, indicating the involvement of anisotropic cellular/subcellular structures for the generation of activity-induced birefringence changes. Polarization imaging has the potential to enhance existing IOS imaging by bringing structural insights into the changes of optical properties induced by neuronal activity in the brain.

Author Contributions

T. Tominaga, M.K.-T., R.O., and T. Tani designed the research. T. Tominaga, M.K.-T., and T. Tani performed the experiments. M.K.-T. and T. Tani analyzed the data. M.K.-T., T. Tani, and R.O. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Shalin Mehta for supporting the image analysis of the instantaneous PolScope. We acknowledge Dr. Lawrence B. Cohen for discussions on activity-induced birefringence changes. We acknowledge Ms. Deborah Danaher for providing primary neuronal cultures and Dr. George Augustine for useful comments and suggestions on the structure and function of primary cultured neurons. We thank Drs. Joel Smith and Paul Maddox for kindly offering iodixanol solution. Finally, we all are grateful to the late Dr. Shinya Inoué (1921–2019), the father of quantitative polarized light microscopy, for his generous support and encouragement throughout our studies.

This study was mainly supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM100160 to T. Tani and R.O. and R01 GM114274 to R.O. and T. Tani, as well as by institutional funds from the Marine Biological Laboratory to T. Tani, M.K.-T., and R.O. This study was also supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant Number JP18K19962 to T. Tani, Grant Numbers JP16H06532, JP16K21743, JP16H06524, JP19H01142, JP19K12190, JP19K22990, and a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Kagaku-Ippan-H30 (18062156)) to T. Tominaga.

Editor: Brian Salzberg.

References

- 1.Grinvald A., Lieke E., Wiesel T.N. Functional architecture of cortex revealed by optical imaging of intrinsic signals. Nature. 1986;324:361–364. doi: 10.1038/324361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frostig R.D., Lieke E.E., Grinvald A. Cortical functional architecture and local coupling between neuronal activity and the microcirculation revealed by in vivo high-resolution optical imaging of intrinsic signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:6082–6086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonhoeffer T., Grinvald A. Iso-orientation domains in cat visual cortex are arranged in pinwheel-like patterns. Nature. 1991;353:429–431. doi: 10.1038/353429a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchida N., Takahashi Y.K., Mori K. Odor maps in the mammalian olfactory bulb: domain organization and odorant structural features. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:1035–1043. doi: 10.1038/79857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blasdel G.G., Salama G. Voltage-sensitive dyes reveal a modular organization in monkey striate cortex. Nature. 1986;321:579–585. doi: 10.1038/321579a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin B.D., Katz L.C. Optical imaging of odorant representations in the mammalian olfactory bulb. Neuron. 1999;23:499–511. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80803-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Farrell A.M., Rex D.E., Toga A.W. Characterization of optical intrinsic signals and blood volume during cortical spreading depression. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2121–2125. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200007140-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacVicar B.A., Hochman D. Imaging of synaptically evoked intrinsic optical signals in hippocampal slices. J. Neurosci. 1991;11:1458–1469. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-05-01458.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rungta R.L., Choi H.B., MacVicar B.A. The cellular mechanisms of neuronal swelling underlying cytotoxic edema. Cell. 2015;161:610–621. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrew R.D., Adams J.R., Polischuk T.M. Imaging NMDA- and kainate-induced intrinsic optical signals from the hippocampal slice. J. Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2707–2717. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.4.2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchheim K., Wessel O., Meierkord H. Processes and components participating in the generation of intrinsic optical signal changes in vitro. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;22:125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]