Abstract

Fluorine incorporation is ideally suited to many NMR techniques, and incorporation of fluorine into proteins and fragment libraries for drug discovery has become increasingly common. Here, we use one-dimensional 19F NMR lineshape analysis to quantify the kinetics and equilibrium thermodynamics for the binding of a fluorine-labeled Src homology 3 (SH3) protein domain to four proline-rich peptides. SH3 domains are one of the largest and most well-characterized families of protein recognition domains and have a multitude of functions in eukaryotic cell signaling. First, we showe that fluorine incorporation into SH3 causes only minor structural changes to both the free and bound states using amide proton temperature coefficients. We then compare the results from lineshape analysis of one-dimensional 19F spectra to those from two-dimensional 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectra. Their agreement demonstrates that one-dimensional 19F lineshape analysis is a robust, low-cost, and fast alternative to traditional heteronuclear single quantum coherence-based experiments. The data show that binding is diffusion limited and indicate that the transition state is highly similar to the free state. We also measured binding as a function of temperature. At equilibrium, binding is enthalpically driven and arises from a highly positive activation enthalpy for association with small entropic contributions. Our results agree with those from studies using different techniques, providing additional evidence for the utility of 19F NMR lineshape analysis, and we anticipate that this analysis will be an effective tool for rapidly characterizing the energetics of protein interactions.

Significance

19F NMR spectroscopy is increasingly employed in biophysical studies of proteins, including drug discovery efforts, because of its sensitivity, simplicity, and lack of background. Src homology 3 domains, one of the most common eukaryotic protein motifs, participate in essential cellular processes. Here, we analyze the interaction kinetics of four proline-rich peptides with their cognate Src homology 3 domain using 19F NMR lineshape analysis. We then verify the robust nature of the method by comparing the 19F-derived activation and equilibrium parameters with those derived from established heteronuclear single quantum coherence-based experiments. We anticipate widespread use of this method for rapid quantification of protein-protein and protein-ligand interactions that occur on the millisecond timescale.

Introduction

Fluorine labeling of proteins is an increasingly attractive strategy for monitoring protein-ligand and protein-protein interactions (1, 2, 3). Additionally, fluorinating pharmaceuticals has several positive effects, including enhanced binding and metabolic stability (4), and there are numerous fluorine compound and fragment libraries for drug discovery (5, 6, 7). It has also been suggested that the kinetics of drug-protein interactions are as important as KD or half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values when considering hit-to-lead optimization and designing an effective, bioavailable therapeutic (8, 9, 10, 11, 12). Here, we show how combining fluorine labeling of a protein (13), 19F NMR, and lineshape analysis can provide quantitative, low-cost access to the kinetics and equilibrium thermodynamics of protein-peptide interactions.

Advantages of 19F protein NMR include its low cost in terms of isotopes and spectrometer time. Additional advantages include the high sensitivity of 19F (83% that of 1H), its large chemical shift range, the 100% abundance of 19F, the near nonexistence of background, the absence of water suppression, the minimal pulse program, and the simplicity of spectra (14). These advantages have led to the increased use of protein- and ligand-observed 19F NMR for the screening of compound and fragment libraries for drug discovery (1,2,15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20). The method used here, 19F NMR lineshape analysis, provides both affinities (KD) and rate constants (kon and koff). Furthermore, the method is particularly efficient at quantifying weak and rapidly associating complexes, which are characteristics of many biologically relevant interactions and initial hits in drug screens.

NMR is a particularly useful tool for characterizing systems undergoing chemical exchange, and a variety of experiments are available for investigating a range of binding affinities and kinetics (21,22). The experiment of choice depends on the exchange rate (kex) of the process, which for a simple two-state protein (P)-ligand (L) binding interaction, is dictated by the equilibrium:

| (1) |

For which, kex is defined as follows:

| (2) |

kon is the association rate constant, koff is the dissociation rate constant, and koff/kon equals the dissociation constant, KD.

The timescale of the process is key to selecting the NMR method and depends on the relationship between kex and the difference in chemical shift between the two states (Δω). The fast and slow timescales apply when kex > Δω and kex < Δω, respectively. The intermediate NMR timescale applies when kex is on the same order of magnitude as Δω between the free and bound states (kex ∼ Δω). Typical chemical shift differences for many protein interactions, including the one studied here, correspond to frequencies of 100–1000 s−1, making them amenable to study by lineshape analysis.

Lineshape analysis is useful for characterizing processes in which kex is ∼0.01–100 ms and in which a combination of differences in chemical shift and line broadening are observed as a function of ligand concentration. The analysis (23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29) involves the simultaneous fitting of parameters that describe the resonances of the free and bound states, including the chemical shifts, the transverse relaxation rates (R2), the population of each state, and the parameters that dictate binding, including the KD, kon, koff, [P], and [L].

Interactions between Src homology 3 (SH3) domains and proline-rich regions typically fall within the ms timescale necessary for lineshape analysis, are prominent in signal transduction, and are one of the most well-characterized classes of peptide recognition modules (30). We studied the 6.8 kDa N-terminal SH3 domain from Drosophila melanogaster, which we refer to as SH3. We introduced the stabilizing mutation T22G (31,32) to eliminate complications of coupled folding and binding. Genetic and biochemical analysis of the sevenless signaling pathway in Drosophila revealed four SH3 binding motifs within the son of sevenless protein (SOS) (33,34). The sites lie within the disordered C-terminus of SOS and have the following sequences: EVSVPAPHLPKK (PepS1), YRAVPPPLPPRR (PepS2), QAPDAPTLPPRDG (PepS3), and GELSPPPIPPRL (PepS4). To our knowledge, these are the first experiments that determine KD, kon, and koff for these SH3-peptide interactions from D. melanogaster. The SH3-SOS interactions are key mediators in the Ras/MAPK signaling cascade that is essential for eukaryotic cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis and is often implicated in many cancers (35) and other disorders (36).

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

A pET11d plasmid containing the gene for the T22G mutant (31,37) of drkN SH3 was transformed into BL21-Gold(DE3) cells by heat shock. A single colony was used to inoculate 5 mL of Lennox Broth (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, and 5 g/L NaCl) supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin. The culture was incubated with shaking at 37°C. After 8 h, 200 μL was used to inoculate 200 mL of supplemented M9 minimal media (50 mM Na2HPO4, 20 mM KH2PO4, 9 mM NaCl, 4 g/L glucose, 1 g/L NH4Cl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgSO4, 10 mg/L biotin, 10 mg/L thiamine, and 100 mg/L ampicillin; isotopically enriched protein was made using 15NH4Cl). This culture was shaken at 37°C for 16 h. 100 mL was then used to inoculate 900 mL of supplemented M9 minimal media. The culture was shaken at 37°C. To optimize labeling, 1 g glyphosate, 60 mg Phe, 60 mg Tyr, and 60 mg 5-fluoroindole were added to each L culture when the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.6. The cultures were shaken for 30 min and then induced with isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside at a final concentration of 1 mM. Protein was expressed at 37°C for 2.5 h or at 20°C for 12 h.

SH3 T22G was purified as described (37). After dialysis, the protein concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm (ε = 8400 M−1⋅cm−1) (38), aliquoted, flash frozen, and lyophilized for 12 h. The protein concentration was verified using 19F NMR and a set of 5-fluoroindole standards (39). Each batch of protein was subjected to electrospray ionization mass spectrometry on a Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) Q Exactive HF-X to assess purity and fluorine incorporation (observed 6833.3 Da and expected 6833.6 Da) (2,40).

Peptide ligands

The 12-residue peptides (PepS1, PepS2, QAPDAPTLPPRD (PepS3), and PepS4) were purchased from GenScript Biotech, where they were high performance liquid chromatography purified to >98%. The net peptide content was determined by GenScript via elemental nitrogen analysis. We dissolved the peptides in 17 MΩ⋅cm H2O and lyophilized the aliquots for 12 h.

NMR

Experiments were conducted on a Bruker (Billerica, MA) AVANCE III HD spectrometer equipped with a quadruple resonance NMR inverse cryogenic probe operating at a Larmor frequency of 470 MHz for 19F, 500 MHz for 1H, and 50 MHz for 15N. One-dimensional (1D) 19F experiments were acquired with a total relaxation delay of 5 s, a sweep width of 30 ppm, and a transmitter frequency offset of −130 ppm. Two-dimensional (2D) 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra were acquired using a Bruker library pulse sequence. Sweep widths of 45 ppm in F1 and 16 ppm in F2 were used with transmitter frequency offsets of 115 and 4.7 ppm for 15N and 1H, respectively. A total of 128 and 2048 points were acquired in t1 and t2, respectively. Eight transients were acquired per increment.

Data were acquired in 50 mM Hepes/bis-tris propane/sodium acetate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 5% D2O to lock the spectrometer and 0.1% sodium trimethylsilyl propanesulfonate (DSS) for chemical shift referencing. For titrations, a stock solution of SH3 T22G was prepared in the buffer above. 1D 19F and/or 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra were first collected on protein in buffer. The stock solution of SH3 T22G was then used to solubilize the lyophilized peptide. The remaining titration samples were made by diluting each previous sample with the SH3 stock. PepS2 and PepS4 concentrations of 0, 29, 73, 145, 218, 290, 435, 580, 870, 1160, and 1450 μM were used. The concentrations were doubled for PepS3 and increased sixfold for the single titration of PepS1. A 1H-15N HSQC spectrum and/or a 19F spectrum was acquired at each peptide concentration. For every sample, a 1D 1H experiment with excitation sculpting for solvent suppression was acquired to enable chemical shift referencing to DSS.

30 mol equivalents of PepS2, PepS3, and PepS4 and 60 mol equivalents of PepS1 were used to obtain 1H and 15N chemical shifts of bound SH3 T22G.

NMR data processing and analysis

Data were processed using NMRPipe. Spectra were either directly (1H) or indirectly (15N, 19F) referenced to DSS (41,42). 19F spectra were processed with a 5 Hz exponential line broadening function. HSQC spectra were processed with a 4.0 and 8.0 Hz exponential line broadening function in the direct and indirect dimensions, respectively. Crosspeak assignments are based on Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank, BMRB: 5923 (31).

Amide proton temperature coefficients (Δδ(1HN)/ΔT), in ppb/K, for SH3 T22G in the free and peptide-bound states were determined from the slope of amide proton chemical shift versus temperature plots for each residue. Uncertainties were determined from the 95% confidence interval of the linear regression. When calculating differences in temperature coefficients between the free and bound states , the uncertainty was determined by error propagation (43) from the individual values.

2D lineshape analysis with 1H-15N HSQC spectra was performed with the TITAN application in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) (29) using the solution to the Bloch-McConnell equations for two-state binding. At least eight SH3 T22G crosspeaks were used for analysis and determination of binding parameters. The residues were selected based on composite chemical shift perturbations (44) (CSPs). Residues with CSPs greater than the average for peptide binding to SH3 and those with minimal peak overlap were chosen for analysis (Fig. 2). The chemical shifts and linewidths of unbound SH3 were fit using the first spectrum only (SH3 alone). Other chemical shifts and binding parameters were determined using the entire data set.

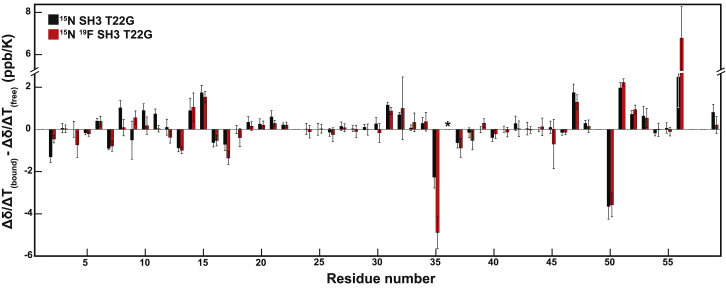

Figure 2.

Difference in Δδ(1HN)/ΔT for the free and PepS4-bound state of SH3 with fluorine (red) and without fluorine (black). No bar indicates no data. W36 is starred because Δδ(1HN)/ΔT is positive in the bound state. Uncertainties were determined by error propagation of the 95% confidence intervals of the slopes from Δδ/ΔT(complex) and Δδ/ΔT(free). To see this figure in color, go online.

1D 19F lineshape analysis was performed using MATLAB and the solution to the Bloch-McConnell equations for two-state binding (45,46). The NMRPipe-processed spectra were converted to text files, which were used as input for the MATLAB script. Nonlinear least-squares fitting was used to obtain simulated lineshapes based on initial input parameters and the solution to the Bloch-McConnell equations for two-state binding until a minimum in the sum of squares was reached. Initial input parameters included the chemical shift (δ) of the free and bound state, the transverse relaxation rate (R2) of the free and bound state, the dissociation constant (KD), and the dissociation rate constant (koff). For 1D and 2D lineshape analysis, errors in the individual fitted parameters are less than the error from replication.

Results

Effect of 19F labeling on SH3 structure

We incorporated fluorine at carbon 5 of W36, the sole tryptophan in SH3, which is located within the binding interface, by expressing the protein in Escherichia coli in the presence of 5-fluoroindole (13). Although the atomic radii of hydrogen and fluorine are similar, 1.10 and 1.47 Å, respectively (47), fluorine is more electronegative (2.1 and 4.0, respectively) (48,49), which could affect structure. To assess the effect of fluorine labeling on SH3, we compared 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the protein with and without fluorine (Fig. S1 A). Inspection of the spectra shows minimal changes, except for a few crosspeaks. To quantify the changes, we calculated the composite CSPs (44) (Fig. S1 B; Table S1):

| (3) |

Three residues, L17, S18, and I48, show values greater than two SDs above the mean. Analysis of the structure (Protein Data Bank, PDB: 2A37) shows that the backbone nitrogen atoms of these residues are close to the W36 side chain (7.7 Å for L17, 9.0 Å for S18, and 4.8 Å for I48).

We then measured the amide proton temperature coefficients, Δδ(1HN)/ΔT, which provide information about local thermally induced melting, affording insight into the probability that a particular residue participates in an intramolecular hydrogen bond (50,51). Inspection of the data (Fig. S1 C) shows that the coefficients are the same for SH3 T22G with 5-fluorotryptophan or tryptophan at position 36. This observation indicates that the fluorine atom minimally perturbs the structure of SH3, suggesting the 19F-labeled protein will yield valid information about the unlabeled protein. The temperature coefficients also match those for folded, wild-type SH3 (52). These results provide a strong structural basis for interpreting van’t Hoff and Eyring data from the labeled protein in terms of unmodified SH3.

Specific binding of SOS peptides

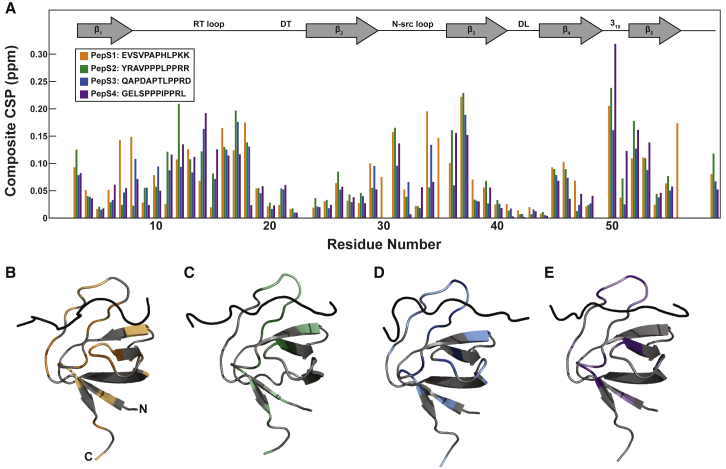

Although the SH3 binding sites within SOS were identified over 25 years ago through peptide competition assays (33,34), there have been no additional biophysical studies to characterize the interactions between this SH3 domain and the four proline-rich peptides. Therefore, we confirmed the specificity of these interactions at the residue level. CSPs for binding of all four peptides show similar patterns (Fig. 1 A; Tables S2–S5). In agreement with studies of other SH3-peptide interactions (53, 54, 55, 56), larger CSPs occur in the loops, specifically the RT and the n-Src loops.

Figure 1.

SH3 T22G specifically binds the four SOS peptides. (A) Shown are CSPs of SH3 T22G upon PepS1 binding at 5°C and PepS2, PepS3, and PepS4 at 45°C. PepS1 is reported at 5°C because binding is weak at 45°C. The secondary structure is annotated at the top of the panel. Composite CSPs were determined using the following equation: . Perturbations are mapped on the computationally determined peptide-docked structures for PepS1 (B), PepS2 (C), PepS3 (D), and PepS4 (E). Structures were derived using the CABS-Dock server (57,58,113). N- and C-termini are labeled in (B). Gray residues indicate regions in which changes are less than the average CSP or for which no data are available. Colored residues indicate CSPs greater than the average. Color intensity increases with increasing CSP. See Figs. S2–S6 and Tables S2–S5 for details. To see this figure in color, go online.

Models for the complexes (Fig. 1, B–E) were produced using the CABS-Dock web server (57,58). First, 10 docked structures for each peptide-SH3 complex were generated along with a contact map highlighting the interface residues between the peptide and SH3. The choice of a final structure was based on the following criteria: correct binding site (53,54), correct peptide orientation in the binding site (59, 60, 61), and contact map information. The residues for which the CSP is greater than the average for all SH3 residues in a particular complex are colored in the docked structures (Figs. 1, B–E and S3–S6). The models in which the contact map most resembles the trends in CSPs and corresponds to known interactions were chosen as the final docked structures. Taken together, the data and computationally docked structures indicate that the peptides bind the same site on SH3, and the site is maintained in the labeled protein.

Effect of 19F labeling on peptide-bound SH3

To assess the effect of labeling on the SH3-peptide interactions, we examined CSPs between the free and bound state for labeled and unlabeled SH3, the temperature dependence of the CSPs, and Δδ(1HN)/ΔT in the peptide-bound states. We confirmed that labeling minimally perturbs the bound state structure by assessing the CSPs caused by peptide binding with and without 5-fluorotryptophan (Fig. S2). The trends are similar for all peptides in the bound state with and without 5-fluorotryptophan. The similarity holds from 5 to 45°C (Tables S2–S5), suggesting the absence of labeling-induced structural changes in the bound state at any of the temperatures.

To corroborate these results, we assessed Δδ(1HN)/ΔT for the peptide-bound states. Similar to our analysis of the free state, we compared amide temperature coefficients for the PepS2-, PepS3-, and PepS4-bound states with and without labeling (Fig. S7). The temperature coefficients are nearly identical for the bound state of SH3 with and without fluorine, suggesting that fluorine incorporation minimally perturbs the bound structure. Δδ(1HN)/ΔT values for PepS1-bound SH3 were not obtained because dissociation was apparent at higher temperatures even with 60 mol equivalents of peptide.

Finally, to assess structural changes upon complexation, we plotted the difference in Δδ(1HN)/ΔT between the free and bound states using the following equation:

| (4) |

The results for PepS4-bound SH3 are shown in Fig. 2. The black bars are similar to the red bars, indicating a minimal difference between binding with and without 5-fluorotryptophan. Several residues have differences in temperature coefficients that are larger in magnitude than ±1 ppb/K. The majority of these residues are either at the termini of SH3, which are flexible and dynamic, or within the binding interface, indicative of binding-induced structural change. These results allow us to interpret temperature-dependent binding parameters with the assumption that temperature is minimally perturbing to free and bound state structures. We obtained similar results for the PepS2- and PepS3-bound states (Fig. S7). Others report similar trends for a different SH3-peptide interaction (62). We conclude that the temperatures used here minimally perturb the structure of free and bound SH3, which simplifies interpretation of the temperature dependence of peptide binding presented later.

We observed positive Δδ(1HN)/ΔT values for W36 in the PepS2-bound state with and without 5-fluorotryptophan and the PepS4-bound state without 5-fluorotryptophan. Δδ(1HN)/ΔT values are rarely positive, but a few examples have been reported (50). First, we discuss the physical basis of negative temperature coefficients. Thermal motion increases with temperature and therefore so do hydrogen bond lengths. An increase in bond length reduces the deshielding induced by the acceptor hydrogen, increasing upfield shifts, which yields negative values of Δδ(1HN)/ΔT. One explanation for positive Δδ(1HN)/ΔT values is the presence of a ring current effect (50,63). For W36, this situation probably arises from the proximity of aromatic residues Y37, Y52, and F9, which are crucial to peptide binding (53,54,64,65). An analysis of a similar interaction discusses the ring current effects arising from these residues (64). Binding probably induces a small conformational change in and around the aromatic residues, causing the amide proton of W36 to be more shielded, resulting in a positive value for the PepS2- and PepS4-bound states. The observation that Δδ(1HN)/ΔT values are negative for the PepS3-bound states suggests subtle structural differences between the binding of PepS3 versus PepS2 and PepS4.

Lineshape analysis using 1D 19F and 2D 1H-15N NMR data provide equivalent binding parameters

NMR is often employed to monitor protein interactions because it provides residue-specific information with no structural perturbation. Such experiments typically use 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra in which plots of chemical shift versus ligand concentration are analyzed to yield KD (21,66). The method works well if kex > Δω. Many interactions, including signaling interactions like the one studied here, however, occur on a ms timescale in which neither chemical shifts nor peak intensities are linearly related to binding. Lineshape analysis (23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29) enables proper fitting of such data. We applied lineshape analysis to both 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra and 1D 19F spectra and compared the results.

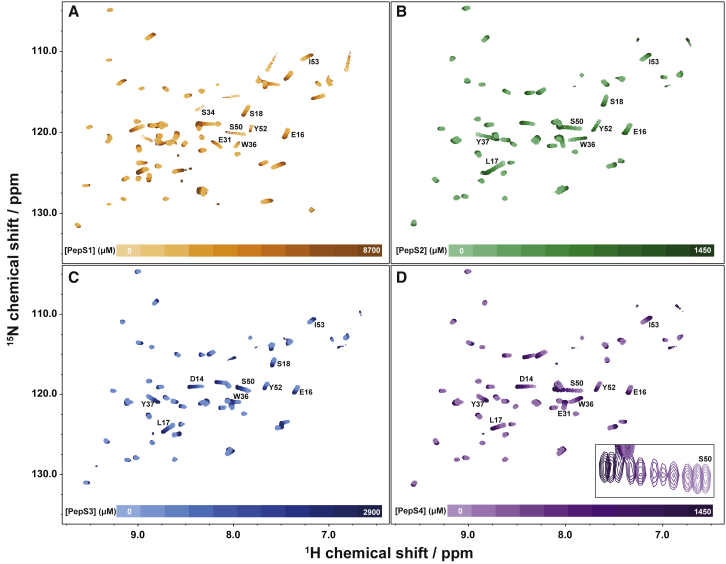

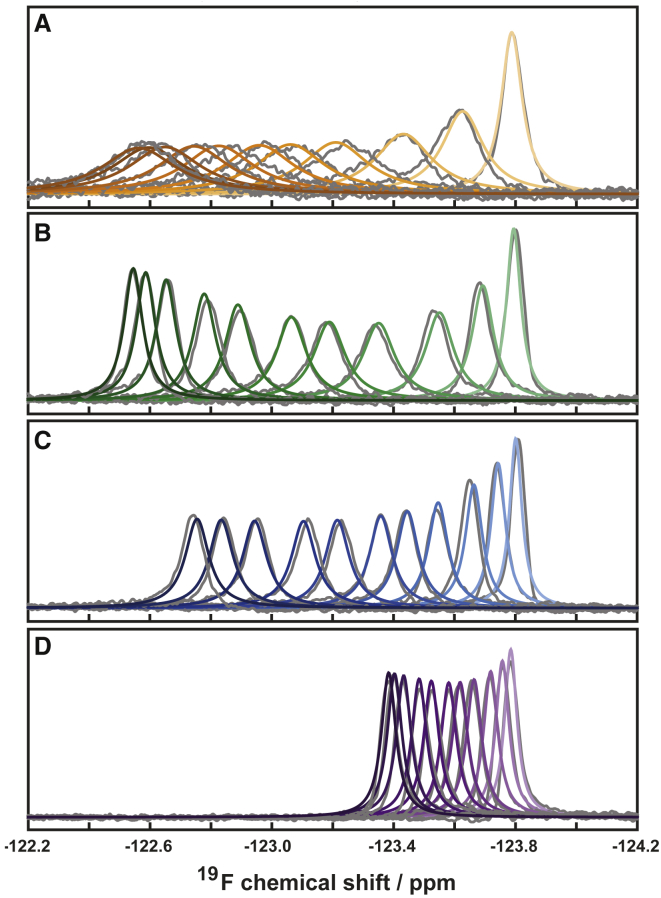

Analysis of 2D spectra is valuable because it provides residue-specific information (Fig. 3) that identifies binding sites within a protein. Labeled residues in Fig. 3 indicate the crosspeaks utilized in 2D analysis to obtain KD, kon, and koff. TITAN software simulates complete 2D spectra to fit multiple parameters, including the chemical shifts and linewidths of free and bound states for each residue, along with the global parameters KD, kon, and koff. Iterative fitting provides robust and rigorous analysis (29). 1D lineshape analysis has been used for several decades (23) to characterize titrations, typically by extracting 1H, 15N, or 13C data from multidimensional spectra (25,67, 68, 69). 19F lineshape analysis of peptide binding is shown in Fig. 4, in which the fitted spectra (colored) are overlaid on the raw spectra (gray). Although nearly all residue-specific information is lost using 19F analysis, we show that it is an efficient and quick method for monitoring interaction kinetics.

Figure 3.

1H-15N HSQC spectra for binding of SOS PepS1 at 5°C (A) and PepS2 (B), PepS3 (C), and PepS4 (D) at 45°C to 5-fluorotryptophan-labeled, 15N-enriched SH3 at a field strength of 11.7 T. Each spectrum was acquired with the same number of scans (8), and the concentration of SH3 was constant. Color intensity increases with increasing peptide concentration. Maximal peptide concentrations were 1.4 mM for PepS2 and PepS4, 2.9 mM for PepS3, and 8.7 mM for PepS1. Labels indicate residues used in 2D lineshape analysis with TITAN. Inset in (D) is a zoomed-in region showing the S50 crosspeak. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 4.

19F NMR lineshape analysis for binding of SOS PepS1 at 5°C (A) and PepS2 (B), PepS3 (C), and PepS4 (D) at 45°C to 5-fluorotryptophan-labeled SH3 T22G. Raw spectra are shown in gray and were acquired at a field strength of 11.7 T. Simulated spectra are overlaid in color. Color intensity increases with increasing peptide concentration. The upfield resonance is from unbound SH3 T22G. Maximal peptide concentrations were 1.4 mM for PepS2 and PepS4, 2.9 mM for PepS3, and 8.7 mM for PepS1. To see this figure in color, go online.

The effect of fluorine labeling on PepS2 binding was assessed from HSQC titration experiments using SH3 with and without 5-fluorotryptophan. For bimolecular interactions, association is dictated largely by diffusion and the geometric constraints of the binding site (70). Changing a hydrogen to a fluorine is not expected to affect diffusion because it adds only 18 mass units. Values of Kd, kon, and koff for binding without fluorine are 70 μM, 1.2 × 108 M−1 s−1, and 0.8 × 104 s−1 (Table 1). Values for the fluorine-labeled protein are 150 μM, 1.5 × 108 M−1 s−1, and 2.2 × 104 s−1 (Table 1). These data show that replacing tryptophan with 5-fluorotryptophan at a residue in the binding interface changes the affinity but has little effect on the association rate constant. The increased KD upon incorporation of fluorine is due to an increase in the dissociation rate constant, indicating a decreased lifetime of the 19F-labeled complex.

Table 1.

Equilibrium and Rate Constants from Lineshape Analysis

| Peptide | Temperature (°C) | 1D, 19F |

2D, 1H-15N HSQC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KD (μM) | kon (108 M−1 s−1) | koff (104 s−1) | KD (μM) | kon (108 M−1 s−1) | koff (104 s−1) | ||

| PepS1a | 5 | 1100 | 0.18 | 1.9 | 1100 | 0.30 | 3.4 |

| PepS2 | 45 | 150 ± 10 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 150 ± 10 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.8 |

| PepS2b | 45 | – | – | – | 70 ± 10 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| PepS3 | 45 | 1200 ± 100 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 6 ± 3 | 1200 ± 100 | 0.081 ± 0.005 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| PepS4 | 25 | 60 ± 10 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 60 ± 10 | 0.37 ± 0.08 | 0.19 ± 0.01 |

| PepS4 | 45 | 210 ± 30 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 230 ± 20 | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

Uncertainty not reported because the measurement was made once.

Non-fluorine-labeled SH3 T22G.

We then compared the results from 1D (Fig. 4 B) to 2D (Fig. 3 B) lineshape analysis of PepS2 binding to fluorine-labeled SH3. The parameters are nearly identical (Table 1), proving that 19F lineshape analysis (Fig. 4) provides reliable data with significant time saving; it takes 5 min to obtain the 1D 19F spectrum but at least 20 min to obtain a 2D HSQC spectrum.

The KD values from 1D to 2D lineshape analysis are equivalent for PepS1, PepS3, and PepS4, but there are differences in rate constants (Table 1). Most of the data are from triplicate analyses, but for the weakest binder, PepS1, measurements were performed only once because of the high concentration of peptide required (8.7 mM). PepS3 also binds weakly, particularly at 45°C (1.2 mM KD). Although KD values agree, the rate constants differ. This difference could arise because 2D fitting uses more data. A similar trend is observed for PepS4. The rate constants are more similar for PepS4 at 25°C than at 45°C. An explanation for this observation is that at 45°C, the interaction approaches the fast exchange regime, making it difficult to extract kinetic information because line broadening is less pronounced.

In summary, kinetic parameters from 1D analysis are similar to those from 2D analysis. Importantly, we were able to quantify a KD for all four peptides. Earlier attempts to quantify an IC50 for the interaction between SH3 showed no inhibition for PepS3 (34), and the investigators did not attempt to quantify PepS1 binding. Our results demonstrate the benefit of using NMR to quantify weak protein-protein interactions (71, 72, 73).

Temperature dependence of binding

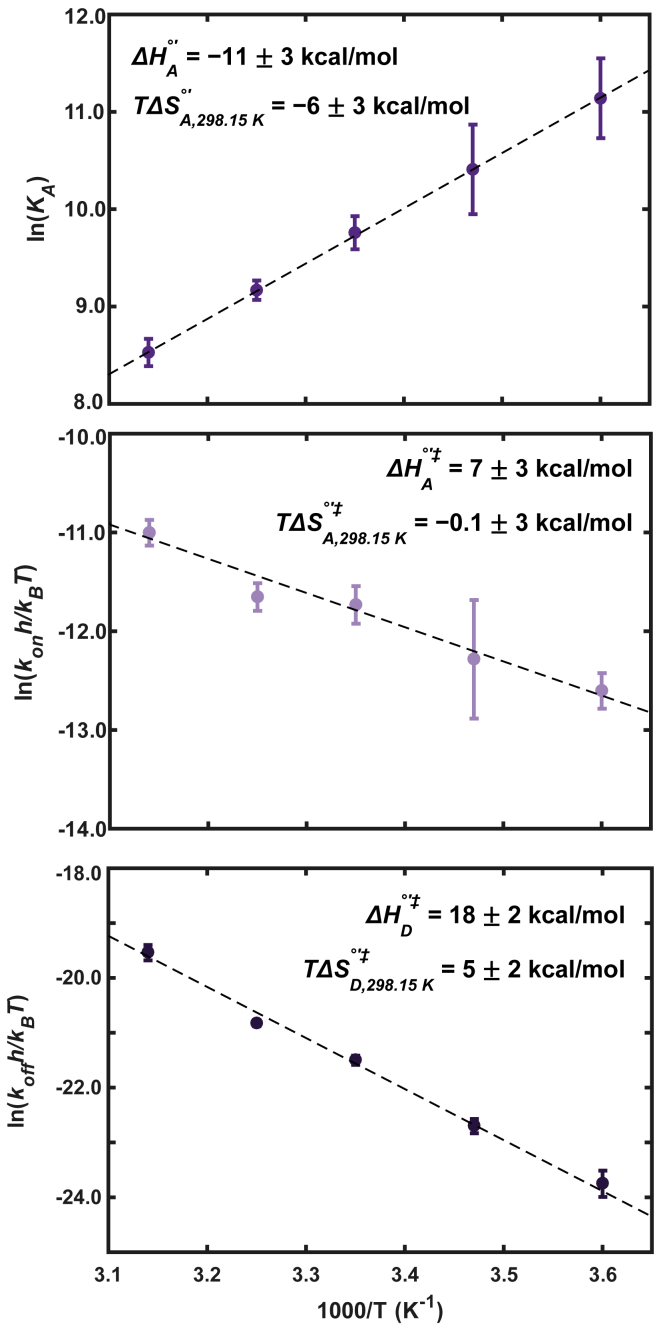

To demonstrate the feasibility of using 1D 19F NMR lineshape analysis to completely characterize binding, we conducted van’t Hoff and Eyring analyses on the formation of the SH3-PepS4 complex using data acquired at 5, 15, 25, 35, and 45°C (Table 2). We first consider the effect of temperature on KD. The dissociation constant increases with temperature as shown by the positive slope of the van’t Hoff plot (Fig. 5). These data provide access to and . At 298 K, binding is accompanied by a favorable enthalpy change, which is partially offset by an unfavorable entropy change, consistent with other results (74).

Table 2.

Temperature Dependence of Rate Constants and Free Energies for SH3 T22G-PepS4 Binding from 19F Lineshape Analysis

| Temperature (°C) | KD (μM) | (kcal/mol) | kon (108 M−1 s−1) | (kcal/mol) | koff (103 s−1) | (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 20 ± 10 | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 0.20 ± 0.07 | 13.1 ± 0.1 |

| 15 | 40 ± 10 | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 7.0 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 13.0 ± 0.1 |

| 25 | 60 ± 10 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 12.7 ± 0.1 |

| 35 | 110 ± 10 | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 0.57 ± 0.08 | 7.1 ± 0.1 | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 12.8 ± 0.1 |

| 45 | 210 ± 30 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 23 ± 3 | 12.3 ± 0.1 |

Figure 5.

van’t Hoff and Eyring analysis for the binding of SH3 to PepS4. van’t Hoff (top) and Eyring plots for association (middle) and dissociation (bottom) are shown. Lines represent linear least-squares fits. Error bars represent standard errors of the mean from at least triplicate measurements. Uncertainties in enthalpy and entropy were determined from 95% confidence interval of the linear fit to all data points. To see this figure in color, go online.

The temperature dependence of kon and koff were analyzed using a linear Eyring analysis (75, 76, 77, 78) because the plots show no curvature (Fig. 5). Both kon and koff values increase with temperature (Table 2). Activation enthalpies and entropies were determined from the slope and y intercept, which are equal to and , respectively (Fig. 5). For association, we obtained an activation enthalpy of association of 7 ± 3 kcal/mol and an entropic component of of 0 ± 3 kcal/mol at 298 K, indicating an enthalpic barrier to association with minimal or no entropic contribution. Dissociation rate constants are more sensitive to temperature than kon (Fig. 5). An activation enthalpy of dissociation of 18 ± 2 kcal/mol and an entropic component of 5 ± 2 kcal/mol at 298 K were determined. The positive values indicate an unfavorable enthalpy change coupled with a favorable entropy of dissociation.

The kinetic and equilibrium results from 1D 19F lineshape analysis are consistent with other reports on SH3-peptide interactions (62,79, 80, 81). The kinetic investigations (62,81) found that dissociation was more sensitive to temperature change than association, and the signs of the energetic terms were the same. Importantly, other reports used alternative techniques including isothermal titration calorimetry (80,81), fluorescence spectroscopy (62,79), ZZ-exchange NMR (81), and Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill relaxation dispersion NMR (62,81). The broad agreement of our data with those obtained with other biophysical techniques shows that 1D 19F lineshape analysis is robust.

Discussion

Energetics

Knowledge of the equilibrium thermodynamics and kinetics of protein association is critical for illuminating fundamental aspects of biology. Our analysis of the SH3-peptide interaction as a function of temperature using 19F NMR lineshape analysis captures a complete picture of the energetics in buffer. The free energies of dissociation are positive and decrease with increasing temperature, which is typical for SH3-peptide interactions (74). Dissecting the free energy change into its components shows that association is enthalpically dominated, which is also characteristic of these types of interactions (74,82). This favorable enthalpy change likely arises from binding-induced changes in hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions, which are known to drive this type of interaction (80,81,83). The source of the entropic penalty is debated. It could arise from several factors (74), including a loss in peptide motion upon binding (84, 85, 86), reduced SH3 loop (85,87,88) or backbone (89,90) dynamics (85,87), and changes in water-mediated hydrogen bonding (91, 92, 93).

Eyring analysis demonstrates an enthalpic barrier to association and dissociation accompanied by a small to slightly favorable entropy change for association and dissociation. The enthalpic barrier to association, which is consistent with other diffusion-limited, two-state binding interactions (94,95) and the Stokes-Einstein relationship (96,97), is likely associated with the temperature dependence of solvent viscosity (94,98,99). The magnitude of demonstrates a large barrier to dissociation likely due to breaking of inter- and intramolecular interactions that facilitate complex stability, including hydrophobic, electrostatic, and hydrogen bonding interactions. The favorable is likely driven by the increase in conformational freedom of the protein and peptide upon dissociation. The signs and magnitudes of all kinetic and equilibrium thermodynamic parameters agree with other studies of SH3 interactions with proline-rich peptides (62,79,81).

The ability of NMR lineshape analysis to measure the transient kinetics of protein-peptide systems at equilibrium provides an advantage over techniques such as surface plasmon resonance or stopped-flow fluorescence, in which binding is observed within a flowing solution or upon mixing. Our results complement other studies (22,62,81), which taken together, highlight the advantage of using NMR to measure the energetics of protein interactions at equilibrium.

The combination of van’t Hoff and Eyring analyses of the SH3-PepS4 interaction provides insight into the transition state via linear free energy analysis (100, 101, 102), which sheds light on the similarity of the transition state to the end states. A plot of against for the interaction of SH3 with PepS4 (Fig. S8; Table 2) is linear with a slope (the so-called Leffler value (100,101), α) of 0.96, but a plot of against has a slope of −0.04. Parsimonious interpretation suggests that the transition state is similar to the free state (100), in agreement with conclusions from molecular dynamics simulations (83,103) in which a “fuzzy” encounter complex was observed.

Applications and advantages of 19F lineshape analysis

We anticipate that 19F NMR lineshape analysis will have applications beyond those examined here because weak protein-protein interactions are prominent in biology, and their energetics are the subject of drug screening and development. First, we discuss the insights from and the advantages of using 19F NMR lineshape analysis to study SH3-peptide interactions, and then we discuss the characteristics that make it an effective tool for other systems.

We quantified KD, kon, and koff for all four SH3-SOS peptide interactions from D. melanogaster. The results agree with preliminary studies that identified the binding motifs within SOS, determined IC50 values (34), and estimated a KD for PepS2 (104). Combining our results with those from homologous systems (105), including those from humans (82) and Caenorhabditis elegans (85), provides insight into evolutionary similarities. McDonald and co-workers (82) showed that human SOS peptides bind the N-terminal SH3 domain with similar KD values in the low μM range. Here, PepS2 and PepS4 have μM values, whereas PepS1 and PepS3 show low mM affinities. The interactions between the disordered region of SOS (which contains the proline-rich peptide sequences) and the functionally homologous adaptor proteins (105) (drk in D. melanogaster and grb2 in Homo sapiens) are multivalent and allosteric (106, 107, 108, 109), yet their proline-rich regions are divergent. The data presented here and elsewhere (82) highlight the energetic differences between homologs and provide the information that will be required to understand the source of specificity in protein-protein interactions.

We have shown that 19F NMR lineshape analysis is a rapid and efficient way to quantify four specific SH3-peptide interactions, but there remains a multitude of similar interactions about which nothing is known. There are over 300 human SH3 domains (30) that are responsible for a myriad of cellular functions. Additionally, proline-rich regions occur in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes (110) and are the most abundant protein sequence pattern in Drosophila (111). The binding of proline-rich regions often involves multiple aromatic residues within SH3. Therefore, inexpensive and simple 19F labeling of tryptophan via fluoroindole (13), as well as labeling with fluorophenylalanine and fluorotyrosine, will be generally useful (1,2,13). A thorough energetic analysis will complement structural studies (30), provide insight into the mechanisms that drive signaling, and elucidate the sources of binding specificity. 19F NMR lineshape analysis is also useful for comparing ligands. For instance, the four peptides studied here bind the same site (Fig. 1), yet the change in 19F chemical shift between the free and bound states is unique for each peptide (Fig. 2).

Weak protein-protein interactions involving globular proteins, peptides, and intrinsically disordered proteins or regions are essential to biological function and dominate cellular signaling (71,72). The rapid association and dissociation of weak interactions combined with their highly specific nature provide tight environmental control that can be manipulated by therapeutics and therefore is of key interest to the pharmaceutical industry. Importantly, weak interactions such as these often occur on the ms timescale. Such systems are ideally suited for lineshape analysis. Even for systems with exchange rates outside those compatible with lineshape analysis, varying the field or temperature may enable its use. Furthermore, there are many additional NMR-based tools to monitor systems with exchange rates on other timescales (22).

In addition to understanding biologically relevant and weak protein-protein interactions, 19F lineshape analysis complements other methods for drug screening, discovery, and development (1,2,15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20), particularly because many initial hits are weak and often accompanied by transient kinetics. In the service of drug and fragment screening, 19F lineshape analysis enables facile acquisition of quantitative data from simple spectra of labeled proteins or ligands. This simplicity eliminates lengthy experiments and complicated analyses associated with methods requiring extensive residue-level assignments. A particular advantage for hit-to-lead optimization can come from combining lineshape analysis with high-throughput screening of fluorine-labeled proteins (1, 2, 3) or ligands (5,7,12).

Nevertheless, there are some limitations. NMR requires larger amounts of target protein compared to methods such as surface plasmon resonance or plate-based assays. NMR is also limited by the size of the protein or complex. Yet recent advances have increased the upper limit (112), and even for large proteins, hit identification is possible with ligand-observed methods in which ligand signals disappear or broaden upon binding to a large, NMR-invisible protein. Despite these limitations, we anticipate that 19F NMR lineshape analysis will be complementary to other drug discovery methods.

In summary, we thoroughly characterized the effects of 19F incorporation on SH3 structure in the free and bound states. Incorporation caused minimal perturbation. Most importantly, we have shown that 19F NMR lineshape analysis is a robust method for quantifying SH3-peptide interaction energetics by demonstrating agreement with 2D lineshape analysis and with other studies of SH3-peptide interactions. We foresee 19F NMR lineshape analysis as a widely applicable method for studying weak protein interactions and as a valuable tool in the NMR drug discovery and development toolbox.

Author Contributions

S.S.S., J.S.A., and G.J.P. designed experiments. S.S.S. and J.S.A. performed experiments. C.A.W. developed MATLAB scripts. S.S.S., J.S.A., C.A.W., and G.J.P. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Pielak lab for helpful discussions, Brandie Ehrmann for mass spectrometry assistance, Greg Young and Stu Parnham for spectrometer maintenance and helpful discussions, and Elizabeth Pielak for comments on the manuscript.

Research in the G.J.P. lab is supported by the National Science Foundation (MCB 1909664). C.A.W. is supported by the Wellcome Trust (206409/Z/17/Z) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/T002603/1). J.S.A. thanks the University of North Carolina Office of Undergraduate Education for a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship. S.S.S. also thanks the National Institutes of Health for support (T32 GM008570).

Editor: Scott Showalter.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.03.031.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Arntson K.E., Pomerantz W.C. Protein-observed fluorine NMR: a bioorthogonal approach for small molecule discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:5158–5171. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gee C.T., Arntson K.E., Pomerantz W.C. Protein-observed 19F-NMR for fragment screening, affinity quantification and druggability assessment. Nat. Protoc. 2016;11:1414–1427. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Divakaran A., Kirberger S.E., Pomerantz W.C.K. SAR by (protein-observed) 19F NMR. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019;52:3407–3418. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J., Sánchez-Roselló M., Liu H. Fluorine in pharmaceutical industry: fluorine-containing drugs introduced to the market in the last decade (2001-2011) Chem. Rev. 2014;114:2432–2506. doi: 10.1021/cr4002879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalvit C., Fagerness P.E., Stockman B.J. Fluorine-NMR experiments for high-throughput screening: theoretical aspects, practical considerations, and range of applicability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7696–7703. doi: 10.1021/ja034646d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh M., Tam B., Akabayov B. NMR-fragment based virtual screening: a brief overview. Molecules. 2018;23:E233. doi: 10.3390/molecules23020233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalvit C. Ligand- and substrate-based 19F NMR screening: principles and applications to drug discovery. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2007;51:243–271. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoare S.R.J., Fleck B.A., Grigoriadis D.E. The importance of target binding kinetics for measuring target binding affinity in drug discovery: a case study from a CRF1 receptor antagonist program. Drug Discov. Today. 2020;25:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2019.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Benedetti P.G., Fanelli F. Computational modeling approaches to quantitative structure-binding kinetics relationships in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today. 2018;23:1396–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernetti M., Cavalli A., Mollica L. Protein-ligand (un)binding kinetics as a new paradigm for drug discovery at the crossroad between experiments and modelling. MedChemComm. 2017;8:534–550. doi: 10.1039/c6md00581k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barril X., Danielsson H. Binding kinetics in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today. Technol. 2015;17:35–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo D., Heitman L.H., IJzerman A.P. The added value of assessing ligand-receptor binding kinetics in drug discovery. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;7:819–821. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crowley P.B., Kyne C., Monteith W.B. Simple and inexpensive incorporation of 19F-tryptophan for protein NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2012;48:10681–10683. doi: 10.1039/c2cc35347d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerig J.T. Fluorine NMR of proteins. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 1994;26:293–370. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pellecchia M., Bertini I., Siegal G. Perspectives on NMR in drug discovery: a technique comes of age. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:738–745. doi: 10.1038/nrd2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lepre C.A. Library design for NMR-based screening. Drug Discov. Today. 2001;6:133–140. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(00)01616-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lepre C.A. Practical aspects of NMR-based fragment screening. Methods Enzymol. 2011;493:219–239. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381274-2.00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawk L.M.L., Gee C.T., Pomerantz W.C.K. Paramagnetic relaxation enhancement for protein-observed 19F NMR as an enabling approach for efficient fragment screening. RSC Adv. 2016;6:95715–95721. doi: 10.1039/C6RA21226C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jordan J.B., Poppe L., Zhong W. Fragment based drug discovery: practical implementation based on 19F NMR spectroscopy. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:678–687. doi: 10.1021/jm201441k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugiki T., Furuita K., Kojima C. Current NMR techniques for structure-based drug discovery. Molecules. 2018;23:E148. doi: 10.3390/molecules23010148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teilum K., Kunze M.B., Kragelund B.B. (S)Pinning down protein interactions by NMR. Protein Sci. 2017;26:436–451. doi: 10.1002/pro.3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleckner I.R., Foster M.P. An introduction to NMR-based approaches for measuring protein dynamics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1814:942–968. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Binsch G. Unified theory of exchange effects on nuclear magnetic resonance line shapes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969;91:1304–1309. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burton R.E., Busby R.S., Oas T.G. ALASKA: a Mathematica package for two-state kinetic analysis of protein folding reactions. J. Biomol. NMR. 1998;11:355–360. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenwood A.I., Rogals M.J., Nicholson L.K. Complete determination of the Pin1 catalytic domain thermodynamic cycle by NMR lineshape analysis. J. Biomol. NMR. 2011;51:21–34. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9538-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niklasson M., Otten R., Lundström P. Comprehensive analysis of NMR data using advanced line shape fitting. J. Biomol. NMR. 2017;69:93–99. doi: 10.1007/s10858-017-0141-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Günther U.L., Schaffhausen B. NMRKIN: simulating line shapes from two-dimensional spectra of proteins upon ligand binding. J. Biomol. NMR. 2002;22:201–209. doi: 10.1023/a:1014985726029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kovrigin E.L. NMR line shapes and multi-state binding equilibria. J. Biomol. NMR. 2012;53:257–270. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waudby C.A., Ramos A., Christodoulou J. Two-dimensional NMR lineshape analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24826. doi: 10.1038/srep24826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teyra J., Huang H., Sidhu S.S. Comprehensive analysis of the human SH3 domain family reveals a wide variety of non-canonical specificities. Structure. 2017;25:1598–1610.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bezsonova I., Singer A., Forman-Kay J.D. Structural comparison of the unstable drkN SH3 domain and a stable mutant. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15550–15560. doi: 10.1021/bi0512795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mok Y.K., Elisseeva E.L., Forman-Kay J.D. Dramatic stabilization of an SH3 domain by a single substitution: roles of the folded and unfolded states. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;307:913–928. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olivier J.P., Raabe T., Pawson T. A Drosophila SH2-SH3 adaptor protein implicated in coupling the sevenless tyrosine kinase to an activator of Ras guanine nucleotide exchange, Sos. Cell. 1993;73:179–191. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90170-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raabe T., Olivier J.P., Hafen E. Biochemical and genetic analysis of the Drk SH2/SH3 adaptor protein of Drosophila. EMBO J. 1995;14:2509–2518. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burotto M., Chiou V.L., Kohn E.C. The MAPK pathway across different malignancies: a new perspective. Cancer. 2014;120:3446–3456. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tartaglia M., Gelb B.D. Disorders of dysregulated signal traffic through the RAS-MAPK pathway: phenotypic spectrum and molecular mechanisms. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1214:99–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05790.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piszkiewicz S., Gunn K.H., Pielak G.J. Protecting activity of desiccated enzymes. Protein Sci. 2019;28:941–951. doi: 10.1002/pro.3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilkins M.R., Gasteiger E., Hochstrasser D.F. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol. Biol. 1999;112:531–552. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-584-7:531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wider G., Dreier L. Measuring protein concentrations by NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2571–2576. doi: 10.1021/ja055336t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stadmiller S.S., Gorensek-Benitez A.H., Pielak G.J. Osmotic shock induced protein destabilization in living cells and its reversal by glycine betaine. J. Mol. Biol. 2017;429:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maurer T., Kalbitzer H.R. Indirect referencing of 31P and 19F NMR spectra. J. Magn. Reson. B. 1996;113:177–178. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wishart D.S., Bigam C.G., Sykes B.D. 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift referencing in biomolecular NMR. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00211777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor J.R. 1982. An Introduction to Error Analysis (University Science Books) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davison T.S., Nie X., Arrowsmith C.H. Structure and functionality of a designed p53 dimer. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;307:605–617. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mcconnell H.M. Reaction rates by nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Chem. Phys. 1958;28:430–431. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abergel D., Palmer A.G. Approximate solutions of the Bloch-McConnell equations for two-site chemical exchange. ChemPhysChem. 2004;5:787–793. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200301051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mantina M., Valero R., Truhlar D.G. Atomic radii of the elements. In: Rumble J.R., editor. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. (Internet Edition) CRC Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allred A.L. Electronegativity values from thermochemical data. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1961;17:215–221. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pauling L. The nature of the chemical bond IV. The energy of single bonds and the relative electronegativity of atoms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1932;54:3570–3582. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cierpicki T., Otlewski J. Amide proton temperature coefficients as hydrogen bond indicators in proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 2001;21:249–261. doi: 10.1023/a:1012911329730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tomlinson J.H., Williamson M.P. Amide temperature coefficients in the protein G B1 domain. J. Biomol. NMR. 2012;52:57–64. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9583-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gorensek-Benitez A.H., Smith A.E., Pielak G.J. Cosolutes, crowding, and protein folding kinetics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:6527–6537. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b03786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wittekind M., Mapelli C., Mueller L. Solution structure of the Grb2 N-terminal SH3 domain complexed with a ten-residue peptide derived from SOS: direct refinement against NOEs, J-couplings and 1H and 13C chemical shifts. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267:933–952. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wittekind M., Mapelli C., Mueller L. Orientation of peptide fragments from Sos proteins bound to the N-terminal SH3 domain of Grb2 determined by NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1994;33:13531–13539. doi: 10.1021/bi00250a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaneko T., Li L., Li S.S. The SH3 domain--a family of versatile peptide- and protein-recognition module. Front. Biosci. 2008;13:4938–4952. doi: 10.2741/3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aitio O., Hellman M., Permi P. Structural basis of PxxDY motif recognition in SH3 binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;382:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blaszczyk M., Kurcinski M., Kmiecik S. Modeling of protein-peptide interactions using the CABS-dock web server for binding site search and flexible docking. Methods. 2016;93:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurcinski M., Jamroz M., Kmiecik S. CABS-dock web server for the flexible docking of peptides to proteins without prior knowledge of the binding site. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W419–W424. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dalgarno D.C., Botfield M.C., Rickles R.J. SH3 domains and drug design: ligands, structure, and biological function. Biopolymers. 1997;43:383–400. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1997)43:5<383::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zarrinpar A., Bhattacharyya R.P., Lim W.A. The structure and function of proline recognition domains. Sci. STKE. 2003;2003:RE8. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.179.re8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simon J.A., Schreiber S.L. Grb2 SH3 binding to peptides from Sos: evaluation of a general model for SH3-ligand interactions. Chem. Biol. 1995;2:53–60. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zeng D., Bhatt V.S., Cho J.H. Kinetic insights into the binding between the nSH3 domain of CrkII and proline-rich motifs in cAbl. Biophys. J. 2016;111:1843–1853. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Merutka G., Dyson H.J., Wright P.E. ‘Random coil’ 1H chemical shifts obtained as a function of temperature and trifluoroethanol concentration for the peptide series GGXGG. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;5:14–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00227466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Terasawa H., Kohda D., Inagaki F. Structure of the N-terminal SH3 domain of GRB2 complexed with a peptide from the guanine nucleotide releasing factor Sos. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1994;1:891–897. doi: 10.1038/nsb1294-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu H., Chen J.K., Schreiber S.L. Structural basis for the binding of proline-rich peptides to SH3 domains. Cell. 1994;76:933–945. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Williamson M.P. Using chemical shift perturbation to characterise ligand binding. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2013;73:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kern D., Kern G., Drakenberg T. Kinetic analysis of cyclophilin-catalyzed prolyl cis/trans isomerization by dynamic NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13594–13602. doi: 10.1021/bi00041a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mittag T., Schaffhausen B., Günther U.L. Tracing kinetic intermediates during ligand binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9017–9023. doi: 10.1021/ja0392519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Günther U., Mittag T., Schaffhausen B. Probing Src homology 2 domain ligand interactions by differential line broadening. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11658–11669. doi: 10.1021/bi0202528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schreiber G., Haran G., Zhou H.X. Fundamental aspects of protein-protein association kinetics. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:839–860. doi: 10.1021/cr800373w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perkins J.R., Diboun I., Orengo C. Transient protein-protein interactions: structural, functional, and network properties. Structure. 2010;18:1233–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Acuner Ozbabacan S.E., Engin H.B., Keskin O. Transient protein-protein interactions. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2011;24:635–648. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzr025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vinogradova O., Qin J. NMR of Proteins and Small Biomolecules. Springer; 2012. NMR as a unique tool in assessment and complex determination of weak protein-protein interactions; pp. 35–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ladbury J.E., Arold S.T. Energetics of Src homology domain interactions in receptor tyrosine kinase-mediated signaling. Methods Enzymol. 2011;488:147–183. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381268-1.00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eyring H. The activated complex and the absolute rate of chemical reactions. Chem. Rev. 1935;17:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Laidler K.J., King M.C. Development of transition-state theory. J. Phys. Chem. 1983;87:2657–2664. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Evans M.G., Polanyi M. Some applications of the transition state method to the calculation of reaction velocities, especially in solution. T. Faraday Soc. 1935;31:875–893. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lente G., Fábián I., Poë A.J. A common misconception about the Eyring equation. New J. Chem. 2005;29:759–760. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bhatt V.S., Zeng D., Cho J.H. Binding mechanism of the N-terminal SH3 domain of CrkII and proline-rich motifs in cAbl. Biophys. J. 2016;110:2630–2641. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Meneses E., Mittermaier A. Electrostatic interactions in the binding pathway of a transient protein complex studied by NMR and isothermal titration calorimetry. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:27911–27923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.553354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Demers J.P., Mittermaier A. Binding mechanism of an SH3 domain studied by NMR and ITC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4355–4367. doi: 10.1021/ja808255d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McDonald C.B., Seldeen K.L., Farooq A. SH3 domains of Grb2 adaptor bind to PXpsiPXR motifs within the Sos1 nucleotide exchange factor in a discriminate manner. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4074–4085. doi: 10.1021/bi802291y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yuwen T., Xue Y., Skrynnikov N.R. Role of electrostatic interactions in binding of peptides and intrinsically disordered proteins to their folded targets: 2. The model of encounter complex involving the double mutant of the c–crk N-SH3 domain and peptide Sos. Biochemistry. 2016;55:1784–1800. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ferreon J.C., Hilser V.J. The effect of the polyproline II (PPII) conformation on the denatured state entropy. Protein Sci. 2003;12:447–457. doi: 10.1110/ps.0237803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ferreon J.C., Hilser V.J. Thermodynamics of binding to SH3 domains: the energetic impact of polyproline II (PII) helix formation. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7787–7797. doi: 10.1021/bi049752m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ogura K., Okamura H. Conformational change of Sos-derived proline-rich peptide upon binding Grb2 N-terminal SH3 domain probed by NMR. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:2913. doi: 10.1038/srep02913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Arold S., O’Brien R., Ladbury J.E. RT loop flexibility enhances the specificity of Src family SH3 domains for HIV-1 Nef. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14683–14691. doi: 10.1021/bi980989q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ferreon J.C., Hilser V.J. Ligand-induced changes in dynamics in the RT loop of the C-terminal SH3 domain of Sem-5 indicate cooperative conformational coupling. Protein Sci. 2003;12:982–996. doi: 10.1110/ps.0238003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cordier F., Wang C., Nicholson L.K. Ligand-induced strain in hydrogen bonds of the c-Src SH3 domain detected by NMR. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;304:497–505. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang C., Pawley N.H., Nicholson L.K. The role of backbone motions in ligand binding to the c-Src SH3 domain. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:873–887. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Palencia A., Cobos E.S., Luque I. Thermodynamic dissection of the binding energetics of proline-rich peptides to the Abl-SH3 domain: implications for rational ligand design. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;336:527–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Palencia A., Camara-Artigas A., Luque I. Role of interfacial water molecules in proline-rich ligand recognition by the Src homology 3 domain of Abl. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:2823–2833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.048033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Martin-Garcia J.M., Ruiz-Sanz J., Luque I. Interfacial water molecules in SH3 interactions: a revised paradigm for polyproline recognition. Biochem. J. 2012;442:443–451. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.van Holde K.E. A hypothesis concerning diffusion-limited protein-ligand interactions. Biophys. Chem. 2002;101–102:249–254. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gabdoulline R.R., Wade R.C. Biomolecular diffusional association. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:204–213. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Frisch C., Fersht A.R., Schreiber G. Experimental assignment of the structure of the transition state for the association of barnase and barstar. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;308:69–77. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xavier K.A., Willson R.C. Association and dissociation kinetics of anti-hen egg lysozyme monoclonal antibodies HyHEL-5 and HyHEL-10. Biophys. J. 1998;74:2036–2045. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(98)77910-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gabdoulline R.R., Wade R.C. Brownian dynamics simulation of protein-protein diffusional encounter. Methods. 1998;14:329–341. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Berg O.G., von Hippel P.H. Diffusion-controlled macromolecular interactions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1985;14:131–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.14.060185.001023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Leffler J.E. Parameters for the description of transition states. Science. 1953;117:340–341. doi: 10.1126/science.117.3039.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fersht A.R. Relationship of Leffler (Bronsted) α values and protein folding ϕ values to position of transition-state structures on reaction coordinates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:14338–14342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406091101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fersht A.R., Wells T.N. Linear free energy relationships in enzyme binding interactions studied by protein engineering. Protein Eng. 1991;4:229–231. doi: 10.1093/protein/4.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xue Y., Yuwen T., Skrynnikov N.R. Role of electrostatic interactions in binding of peptides and intrinsically disordered proteins to their folded targets. 1. NMR and MD characterization of the complex between the c-Crk N-SH3 domain and the peptide Sos. Biochemistry. 2014;53:6473–6495. doi: 10.1021/bi500904f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang O., Forman-Kay J.D. NMR studies of unfolded states of an SH3 domain in aqueous solution and denaturing conditions. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3959–3970. doi: 10.1021/bi9627626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stern M.J., Marengere L.E., Schlessinger J. The human GRB2 and Drosophila Drk genes can functionally replace the Caenorhabditis elegans cell signaling gene sem-5. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1993;4:1175–1188. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.11.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.McDonald C.B., Seldeen K.L., Farooq A. Structural basis of the differential binding of the SH3 domains of Grb2 adaptor to the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Sos1. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008;479:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.McDonald C.B. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. University of Miami; 2009. Physicochemical studies of the Grb2-Sos1 interaction; p. 153. [Google Scholar]

- 108.McDonald C.B., Seldeen K.L., Farooq A. Assembly of the Sos1-Grb2-Gab1 ternary signaling complex is under allosteric control. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010;494:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.McDonald C.B., Balke J.E., Farooq A. Multivalent binding and facilitated diffusion account for the formation of the Grb2-Sos1 signaling complex in a cooperative manner. Biochemistry. 2012;51:2122–2135. doi: 10.1021/bi3000534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ravi Chandra B., Gowthaman R., Sharma A. Distribution of proline-rich (PxxP) motifs in distinct proteomes: functional and therapeutic implications for malaria and tuberculosis. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2004;17:175–182. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rubin G.M., Yandell M.D., Lewis S. Comparative genomics of the eukaryotes. Science. 2000;287:2204–2215. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Foster M.P., McElroy C.A., Amero C.D. Solution NMR of large molecules and assemblies. Biochemistry. 2007;46:331–340. doi: 10.1021/bi0621314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kouza M., Blaszczyk M., Kmiecik S. Protein-peptide docking with high conformational flexibility using CABS-dock web tool. Biophys. J. 2016;110:543a. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.