Abstract

This study investigated temporal relationships between posttraumatic stress symptoms and two indicators of social functioning during Cognitive Processing Therapy. Participants were 176 patients (51.5% female; M age = 39.46 [SD = 11.51]; 89.1% White; 42.6% active duty military/Veteran) who participated in at least two assessment timepoints during a trial of Cognitive Processing Therapy. PTSD symptoms (DSM-IV Posttraumatic Disorder Checklist; PCL), and interpersonal relationship and social role functioning problems (Outcomes Questionnaire-45, OQ-45) were assessed prior to each of 12 sessions. Multivariate multilevel lagged analyses indicated that interpersonal relationship problems predicted subsequent PTSD symptoms (b = .22, SE = .09, cr = 2.53, p = .01, pr = .46), and vice versa (b = .05, SE = .02, cr = 2.11, p = .04, pr = .16); and social role functioning problems predicted subsequent PTSD symptoms (b = .21, SE = .10, cr = 2.18, p = .03, pr = .16), and vice versa (b = .06, SE = .02, cr = 3.08, p < .001, pr = .23). Military status moderated the cross-lag from social role functioning problems to PTSD symptoms (b = −.35, t = −2.00, p = .045, pr = .16). Results suggest a robust association between PTSD symptoms and social functioning during Cognitive Processing Therapy with a reciprocal relationship between PTSD symptoms and social functioning over time. Additionally, higher social role functioning problems for patients with military status indicate smaller reductions in PTSD symptoms from session to session.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, social functioning, Cognitive Processing Therapy

Since the introduction of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) into diagnostic nomenclature (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed., rev.; DSM–III–R; American Psychiatric Association, 1987) research has robustly documented an inverse relationship between PTSD symptoms and dimensions of social functioning. For example, meta-analyses including publications since 1980 investigating risk and resilience factors associated with PTSD have identified social support as one of the variables most strongly associated with PTSD symptoms (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000; Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003). The preponderance of studies establishing these associations have utilized cross-sectional designs, which precludes an examination of the temporal dynamics of the associations. Wagner, Monson, and Hart (2016) identified several different ways that the temporal dynamics might manifest: it may be that social functioning and resources predicts PTSD, that PTSD erodes social functioning and resources, or that both relationships exist concurrently. Few studies have examined the interactions among these factors over the course of treatment for PTSD (Evans et al., 2009). The current study investigated the temporal relationships between PTSD symptoms and two facets of social functioning, specifically, interpersonal problems and social role problems, across 12 sessions of Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT; Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2017) delivered in a randomized controlled implementation trial (Monson et al., 2018).

Social functioning is broadly defined as, “the interaction of an individual with their environment and the ability to fulfill their role within the environment,” (Bosc, 2000). Dissecting that broad definition results in two specific aspects of social functioning: interpersonal functioning, or the quality of interpersonal relationships, and social role functioning, or satisfaction and efficiency in fulfilling social roles, such as occupational work, work in the home, and work at school (Lambert et al., 1996b, 2004b). Interpersonal functioning exists across a variety of relationships, including romantic/intimate, familial, and parental relationships as well as friendships, and social role functioning exists across a variety of environments, including work, home, school, and leisure. Both terms share a focus on difficulties with social demands; however, interpersonal functioning is concerned with one’s ability to successfully interact across relationship domains to maintain satisfying and fulfilling relationships, while social role functioning is concerned with one’s ability to perform work socially expected of them. Social role functioning as defined here may overlap with occupational functioning; however, social role functioning problems extend beyond employment into other roles where individuals are expected to perform work, such as in the home or at school, and focus on difficulties performing role related work (e.g., disagreements, anger, and stress) as opposed to difficulties gaining employment or attending work. To comprehensively assess social functioning, this study assessed the temporal relationships between PTSD symptoms and both aspects of social functioning, namely interpersonal functioning problems and social role functioning problems.

Interpersonal Functioning

The use of the term “social functioning” in the extant literature typically refers to interpersonal functioning as defined here, and accordingly, a majority of the literature investigates the relationships between interpersonal functioning across different types of relationships and PTSD symptoms. Over the past decade, longitudinal research has shed light on the temporal dynamics of the relationship between PTSD symptoms and interpersonal functioning. However, many of these studies assessed PTSD symptoms and/or interpersonal functioning at a baseline period and then evaluated the impact of change on the other variable at a follow-up time point ranging from 2 months to 20 years. These studies have shown support for the “buffering hypothesis” (i.e., social resources reduce PTSD symptomatology over time; Hitchcock, Ellis, Williamson, & Nixon, 2015; Koenen, Stellman, Stellman, & Sommer, 2003; Perry, Difede, Musngi, Frances, & Jacobsberg, 1992), “social causation” (i.e., lack of social resources predicts and potentiates PTSD symptomatology over time; Jones et al., 2012; Manne et al., 2002; Robinaugh et al., 2011), and “social erosion” theories (i.e., PTSD predicts subsequent deterioration in social functioning; Creech, Benzer, Liebsack, Proctor, & Taft, 2013; Laffaye, Cavella, Drescher, & Rosen, 2008; Smith et al., 2017; Solomon & Mikulincer, 2007; Taft, Schumm, Panuzio, & Proctor, 2008; Vogt et al., 2017). Although helpful in beginning to understand the temporal dynamics in the relationship between PTSD symptoms and interpersonal functioning, these studies have not provided a comprehensive examination of the interplay between PTSD symptoms and interpersonal functioning over time due to methodological issues. For example, the majority of longitudinal studies cited above have only two assessment points, with several months or years in between them. Additionally, these studies assess PTSD or interpersonal functioning at each point, precluding investigation of the potential reciprocal associations between the two.

Previous research investigating the potential reciprocal relationship between PTSD and interpersonal functioning over time with cross-lagged analyses have found support for the social erosion hypothesis (Carter et al., 2016; King, Taft, King, Hammond, & Stone, 2006; Shallcross, Freemantle, Nisar, & Ray, 2016), while others have found support for a reciprocal relationship between PTSD and facets of interpersonal functioning (Kaniasty & Norris, 2008; Zerach, Solomon, Horesh, & Ein-Dor, 2013). These later studies demonstrated that the directionality of the relationship depended on the assessment timeframe, highlighting the importance of number and frequency of assessments, and time since traumatization. Although these studies utilized more assessment points than other studies (typically at baseline with three follow-up time points), these assessment points were months to years apart. To more fully elucidate the dynamic association between PTSD and interpersonal functioning, assessments must occur closer together.

Social Role Functioning

Comparatively only two longitudinal studies, to our knowledge, have investigated the temporal dynamics of the relationship between PTSD symptoms and social role functioning. These studies demonstrated that a diagnosis of PTSD predicts lower work/school functioning and satisfaction from one to three and half years later in veteran populations (Erbes, Kaler, Schult, Polusny, & Arbisis, 2011; Vogt et al., 2017). Similar to research investigating interpersonal functioning, these studies only utilized two assessment points with years in between and did not assess these relationships bidirectionally. Furthermore, these studies did not assess home management performance, which is another important social role domain, and did not assess these relationships in civilian populations. Thus, it is not clear how work functioning impacts PTSD symptoms over time, or how these relationships exist dynamically over time, so we are limited in making conclusions about these temporal associations.

Treatment Research

Examining the association between PTSD and social functioning (i.e., interpersonal functioning and social role functioning) during the context of evidence-based PTSD treatment represents a unique context for elucidating the relationship between these constructs for two reasons. First, treatment sessions offer regular and frequent assessment intervals to assess these constructs relative to previous longitudinal research utilizing few and infrequent assessments. Second, treatment aims to manipulate at least one of these factors (i.e., directly trying to reduce PTSD symptoms) and sometimes both (i.e., some PTSD treatments attempt to directly target interpersonal or social role processes; Monson et al., 2012). There is extensive evidence that both PTSD symptoms and interpersonal functioning improve over the course of cognitive-behavioral treatments for PTSD (e.g., Foa et al., 2005; Monson et al., 2012; Wachen, Jimenez, Smith, & Resick, 2014) and limited evidence that occupational functioning improves over the course of cognitive-behavioral treatments for PTSD (e.g., Taylor, Wald, & Asmundson, 2006). However, it remains unclear how social functioning influences subsequent PTSD symptom improvement and vice versa during treatment. Illuminating the directionality of the temporal relationships between PTSD and social functioning during treatment would be informative to prevention and intervention efforts for trauma survivors. Specifically, understanding the effect of social functioning may highlight the importance of intervening to fortify and expand social bonds, or directly support social role functioning to prevent or reduce PTSD symptoms.

We are aware of only one study that has assessed the temporal relationship between PTSD and a single domain of interpersonal functioning over the course of treatment. Evans et al. (2009) assessed family functioning and PTSD symptoms in US veterans participating in a 12-week PTSD treatment program using a three-wave, cross-lagged panel model with assessments at pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 6-month follow-up. Results suggested family functioning at pre-treatment negatively predicted PTSD symptoms at post-treatment and 6-month follow-up, but the reverse was not true, as PTSD symptoms did not significantly predict family functioning at any time point. These findings support the social causation hypothesis and suggest that baseline family functioning influences treatment outcomes. However, this study shares the same methodological limitations as those above: social functioning and PTSD were assessed at three time points that were months apart, none of which were during the course of treatment. Therefore, while the study analyzed change over the course of treatment, they did not analyze change during treatment (i.e.., measuring symptoms at each treatment session). This limits our ability to make conclusions about the potential dynamic interplay between PTSD symptoms and interpersonal functioning during the time they theoretically change. Additionally, the article does not specify what exactly treatment consisted of, and thus, it is unclear whether treatment aimed to decrease PTSD symptoms, increase family functioning, or both. To our knowledge there are no studies that have assessed the temporal relationships between PTSD and social role functioning over the course of treatment, though one study reports that improvements in PTSD symptoms and occupational functioning attributable to cognitive-behavioral treatment were correlated at post-treatment (Taylor, Wald, & Asmundson, 2006).

Macdonald, Monson, Doron-Lamarca, Resick, & Palfai (2011) showed that reductions in PTSD symptoms during CPT are larger during the earlier portion of treatment than the latter portion of treatment. Even only including a mid-treatment assessment (with no assessments between baseline and mid-treatment) fails to adequately account for meaningful change during the initial phase of treatment. Using the Outcome Questionnaire (see Measures section of current study), Bragdon and Lombardo (2012) showed substantial reduction in social role functioning (d = .73) and interpersonal functioning (d = 1.08) problems during a brief (approximately 28 days) written disclosure protocol for PTSD during inpatient treatment for substance abuse disorder. Thus, research shows that PTSD and social functioning change rapidly during cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD, and examining change early on during therapy is important to elucidate temporal, and perhaps causal, relationships among these constructs.

Current Research

The current study builds upon the extant literature by investigating the temporal relationship(s) between interpersonal functioning problems and social role functioning problems, and PTSD symptoms in the context of a randomized controlled implementation trial (Monson et al., 2018) of Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT; Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2017). CPT is an evidence-based, cognitive-behavioral treatment for PTSD consisting of cognitive interventions that help patients challenge and modify unhelpful beliefs related to their trauma typically delivered across 12 sessions (Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2017). PTSD symptoms, interpersonal functioning, and social role functioning were assessed at 12 time points during the course of the trial. This study addresses several methodological gaps by assessing two facets of social functioning (i.e., interpersonal problems and social role problems), examining interpersonal functioning across several interpersonal domains (e.g., intimate partner, parenting, family), examining social role functioning across several environments (e.g., work, home, school), and analyzing these relationships over 12 regularly spaced time-points during treatment using a cross-lagged design. Due to the inconsistent findings of longitudinal studies and the limited number of studies analyzing the relationship between PTSD and interpersonal functioning bidirectionally, and the relative dearth of longitudinal research analyzing the relationship between PTSD and social role functioning, we offer the tentative hypotheses that the relationships between PTSD and interpersonal problems, and PTSD and social role problems will be positive and reciprocal over time, such that social functioning simultaneously improves as PTSD symptoms decrease.

Furthermore, this study is unique due to its diverse sample that includes roughly equal numbers of men and women, active duty/veteran and civilian participants. Thus, this sample addresses the concern that previous research has over relied on predominantly male veteran samples (Monson, Taft, & Fredman, 2009). Furthermore, this sample offers the unique opportunity to analyze military status and gender as moderators of the relationships of interest. A majority of the studies cited here have either utilized all-male military or all female civilian samples, precluding moderator analyses. Results were mixed in the few studies that include more than one gender. Brewin and colleagues’ (2000) meta-analysis suggests that there is a stronger negative relationship between PTSD and social support for individuals in the military, but that this relationship does not differ according to gender, which is consistent with the findings of a more recent meta-analysis that demonstrated that the association between PTSD and relationship discord was stronger in military samples relative to civilian samples (Taft, Watkins, Stafford, Street, & Monson, 2011). Other research, however, suggests stronger relationships between PTSD symptoms and relationship distress for female veterans and female partners of male veterans as opposed to male veterans (Renshaw, Campbell, Meis, & Erbes, 2014). No research to our knowledge has examined gender or military status as moderators of the relationships between PTSD symptoms and social role functioning. Due to the limited literature, we treated these moderation analyses as exploratory.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from 188 individuals who met criteria for PTSD and were enrolled in a nation-wide randomized controlled implementation trial of CPT in Canada (52% female; M age = 39.39 [SD = 11.27]; 88% White; 42.5% military or veteran; see Monson et al., 2018). In brief, clinicians in routine clinical practice who attended a workshop and were learning CPT enrolled patient participants in the study. All participants provided voluntary informed consent after a clear description of the Research Ethics Board-approved study procedures by their study clinician. Participants were identified as eligible by their clinician and enrolled in the trial if they provided informed consent. To be considered eligible to participate, participants must have been diagnosed with PTSD based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria and had to have a Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist – Fourth Edition score of ≥ 501 (Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993). Participants were also required to consent to audio recording of sessions and review of recordings. Participants were permitted to continue adjunctive psychotherapeutic interventions, as long as they were not trauma-focused. Consistent with current research-informed standards, participants were excluded if they had current uncontrolled psychoses or bipolar disorder, substance dependence (abuse was permitted), imminent suicidal or homicidal risk, or significant cognitive impairment (mild to moderate traumatic brain injury was permitted). The sample for this study consisted of 176 individuals (51.5% female; M age = 39.46 [SD = 11.51]; 89.1% White; 42.6% military or veteran) who completed at least two assessment points. Two assessment points were necessary to conduct cross-lag analyses, which excluded 12 patients from the study sample.

Procedure

CPT was provided by 82 clinicians from Veterans Affairs Canada Operational Stress Injury Clinics, Canadian Forces mental health services, and the broader Canadian community in hospitals and private practice (74% female; M age = 47.63 [SD = 9.73]); 41% PhD level, 41% Master’s (counseling, social work). Mental health clinicians were eligible to participate if they met inclusion criteria: attended a 2-day standardized CPT workshop that trained clinicians to administer the CPT protocol including a written trauma account (Resick et al., 2008, 2016), were a licensed clinician with psychotherapy in their scope of practice, were currently providing psychotherapy to individuals with PTSD, consented to be randomized to study conditions, and consented to audio record sessions, as well as collect self-report measures across treatment from consenting patients. At the 2-day CPT training, led by C.M, clinicians received the CPT manual and related materials. They also had access to resources available through the free CPT-web online training (https://cpt.musc.edu/index). After attending the CPT workshop, clinicians were randomly assigned to one of three consultation conditions: 1) Standard consultation (Standard) by expert-CPT providers without session audio review, 2) Tech-enhanced (Standard + Audio) consultation by expert-CPT providers with review of session audio, and 3) No consultation. For a full explanation of consultation and fidelity procedures, see the parent study publications (Monson et al., 2018; Stirman et al., 2013).

Measures

The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-S; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993).

The PCL is a well-validated 17-item self-report questionnaire that assesses the presence and severity of DSM-IV PTSD symptoms on a 5-point Likert scale from not at all to extremely. The timeframe queried was the past month at the baseline session, and the past week at each subsequent session. The PCL-S asks about symptoms in relation to an identified “stressful experience.” The PCL was completed at pre-treatment and prior to every CPT session. The PCL has strong psychometric properties (Wilkins, Lang, & Norman, 2011). The internal consistency of the PCL was high in the current study (α = .87 at baseline).

The Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45; Lambert et al., 1996b).

The OQ-45 is a 45-item self-report measure that assesses patient functioning in the past week across several domains including symptom severity, social role functioning, and interpersonal relationship problems on a 5-point Likert scale from never (0) to almost always (4). The OQ-45 was designed to be repeatedly administered during treatment and to be sensitive to changes in psychological distress over time (Lambert et al., 2004a). Research has established that the majority of items as well as the subscale and total scores are sensitive to change over short periods of time (Vermeersch et al., 2000, 2004). Additionally, the OQ-45 has evidenced good internal consistency (α = .93) and test-retest reliability (r = .79; Lambert et al., 1996a, 1996b, 2004b). We utilized the 10-item interpersonal relationship problems (IR; e.g., “I have frequent arguments.”), and 7-item social role functioning problems (SR; e.g., “I feel stress at work/school”) subscales for these analyses. The OQ-IR scale assesses functioning across a range of relationship types, including family, friends, romantic partners, and acquaintances. The OQ-SR assesses functioning in social roles at work (defined here as employment, school, housework, volunteer work, etc.). Thus, the OQ-SR measures problems fulfilling the role of employee, homemaker, volunteer, student, etc. A score of 15 or more on the OQ-IR and a 12 or more of the OQ-SR indicate clinically significant interpersonal functioning and social role functioning problems (Beckstead et al., 2003; Lambert et al., 1996b, 2004b). Patients completed the OQ-45 at pre-treatment and prior to each treatment session. Cronbach’s alphas were .70 and .71 for the OQ-IR and OQ-SR subscales, respectively, at the baseline assessment.

Data Analyses

The study design produced three levels of nesting: repeated assessments (Level-1) nested within patients (Level-2) nested within clinicians (Level-3). Therefore, we conducted a series of multilevel regression models (unconditional, within-subjects associations, multivariate growth curve, and multivariate lagged) to evaluate the associations between PTSD and OQ-IR scores, as well as PTSD and OQ-SR scores during the course of treatment using the Mplus software package (Version 7; Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012). We first evaluated three-level unconditional models to evaluate the distribution of variance of PTSD, OQ-IR scores, and OQ-SR scores across these three levels of nesting. Then, to evaluate the within-subjects association between the variables, we evaluated models with OQ-IR scores and OQ-SR scores as Level-1 predictors of PTSD symptoms. Examining the within subject associations between the constructs is informative and is one way to look at the associations among the constructs during treatment. However, we were most interested in examining associations among change in the variables (i.e., was the change, or trajectory, in PTSD from baseline to Session 12 correlated with the change in the OQ subscales from baseline to Session 12). Therefore, we added time as a predictor of each outcome and conducted multivariate multilevel growth curve analysis to modeled trajectories of PTSD and OQ-IR scores simultaneously and evaluated the correlation between change in PTSD and change in OQ-IR scores across the course of treatment (through Session 12). We conducted an identical analysis modelling trajectories of PTSD and OQ-SR scores.

As reported in the parent study (Monson et al., 2018), PTSD, OQ-IR, and unconditional change/growth models indicated better model fit with a random quadratic time coefficient included in the growth curve models for PTSD, OQ-IR, and OQ-SR. Therefore, the multilevel lagged analyses described below included linear and quadratic time coefficients. However, for descriptive purposes, to estimate the association between overall change in PTSD symptoms (not taking into account differences in rates of change across time) and overall change in OQ-IR scores, we evaluated a linear multivariate growth model that included both PTSD and OQ-IR scores as outcomes predicted by the number of days since baseline assessment (Baldwin, Imel, Braithwaite, & Atkins, 2014; Suvak, Walling, Iverson, Taft, & Resick, 2009). We conducted an identical analysis with PTSD and OQ-SR scores.

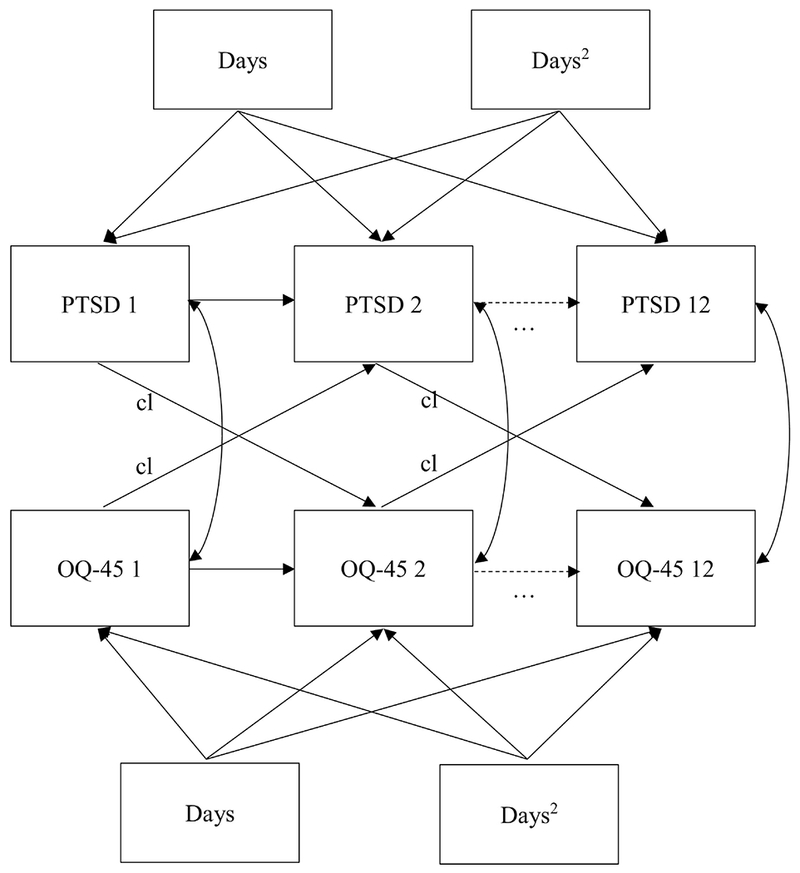

Estimating the correlation of change provides another piece of the puzzle in investigating the relationships among constructs during time, but this provides no information about temporal dynamics (i.e., temporal precedence). Therefore, the final models added paths from previous levels of each variable (time t) to subsequent levels of each variable (time t + 1) to the multilevel, multivariate growth models. This approach is similar to the approach adopted by Zalta et al. (2014) examining the relationship between PTSD and cognitions during treatment. Figure 1 depicts this model. PTSD and OQ-IR scores from the previous assessment as lagged predictors of each of these two outcomes. In addition, time (modeled using a linear [days since the baseline assessment] and quadratic [days since baseline squared] predictor) was included as a predictor of each outcome to account for the decelerating decrease observed in these variables. Zalta et al. (2014) evaluated separate univariate lagged models, one for each outcome. However, we conducted one multivariate lagged analysis that included both PTSD and OQ-IR scores as outcomes, allowing us to evaluate all relevant relationships simultaneously in one model and to account for the correlation among trajectories of the two outcomes by covarying the time effects across outcomes. The “lagged” associations (denoted in Figure 1 as “cl”) between PTSD at Time t and OQ-IR at Time t+1, when controlling for time and OQ-IR at Time t; and between OQ-IR at Time t and PTSD symptoms at Time t+1, when controlling for time and PTSD symptoms at Time t, were evaluated to test the prospective relationships between PTSD symptoms and OQ-IR scores during treatment. We conducted an identical analysis with PTSD and OQ-SR scores.

Figure 1.

Multivariate lagged analysis model. Days = linear time, Days2 = quadratic time. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms as assessed by the PCL. OQ-45 = Outcome Questionnaire scores. Cl indicates the cross-lagged paths. Two identical analyses were conducted with OQ-45 interpersonal functioning problems, and social role functioning as the OQ-45 score of interest. Three time points are presented for readability; however, analyses were conducted over 12 time points.

To evaluate the impact of consultation condition (no, standard, standard + audio; because consultation condition was a significant predictor of outcomes in the parent study), gender (male, female), and military status (civilian versus Veterans and active duty), we entered dummy coded variables as Level-2 (person-level) predictors of all of the Level-1 coefficients depicted in Figure 1. We reported partial regression coefficients (pr) as effect size indicators for the multilevel regression coefficients. Kirk (1996) suggests .10, .24, and .37 for small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

The unconditional models (i.e., models with no predictors) indicated that for PTSD the percentage of variance at each level was 37.28% (p < .001), 61.12% (p < .001), and 1.61% (p = .752) across Level-1 (repeated assessment), Level-2 (within patient), and Level-3 (within clinician), respectively. For OQ-IR scores, the percentage of variance at each level was 21.50% (p < .001), 70.73% (p < .001), and 7.76% (p = .275) across Level-1, Level-2, and Level-3, respectively. Finally, for OQ-SR scores, the percentage of variance at each level was 32.1% (p < .001), 59.5% (p < .001), and 8.4% (p = .202) across Level-1, Level-2, and Level-3, respectively. The amount of variance at Level-3 (i.e., across clinicians) was not statistically significant for any variable; therefore, to simplify the lagged-multilevel analyses, we evaluated two-level models.

The average PCL score prior to treatment was 61.08 (SD = 11.06), which was in the severe range of the scale. The average OQ-IR score was 21.37 (SD = 7.55), suggesting that on average, patients exhibited OQ-IR exceeding the suggested clinical cutoff (≥ 15; Lambert et al., 1996b, 2004b), and the average OQ-SR score was 15.91 (SD = 6.36), again suggesting that on average, patients exhibited SR difficulties exceeding the suggested clinical cutoff (≥ 12). The average amount of change for each outcome for each consultation condition was reported in Monson et al. (2018). To help provide context for the results reported in the current manuscript, we used the models of Monson et al. (2018) to produce estimates of change from baseline through session 12 across the entire sample used in this paper (i.e., n = 176 with two or more assessments). The average reductions were 14.46 (d = 11.06), 2.94 (d = .39), and 2.33 (d = 1.31), on the PCL, OQ-IR, and OQ-SR, respectively; thus, PTSD exhibited large effect size decreases while social functioning as assessed by the two OQ scales fell in the small to medium range. At the initial assessment, there were significant positive correlations between PTSD symptoms and OQ-IR (r = .48, p < .001) and PTSD symptoms and OQ-SR (r = .42, p < .001).

Within-Subjects and Multivariate Growth Associations

A multilevel regression with OQ-IR as a Level-1 predictor of PCL scores indicated a significant positive within-participants association over time between PTSD symptoms and interpersonal relationship problems, b = 1.28, t = 24.92, p < .001, pr = .88. Similarly, a multilevel regression with OQ-SR as a Level-1 predictor of PCL scores indicated a significant positive within-participants association over time between PTSD symptoms and social role problems, b = 1.32, t = 20.73, p < .001, pr = .84.

The multivariate growth model estimating linear slopes for PTSD and OQ-IR indicated a significant positive association between changes in PTSD and changes in interpersonal relationship problems, b = .01, t = 5.51, p < .001, pr = .38. Likewise, significant associations emerged between changes in PTSD and changes in OQ-SR, b = .004, t = 5.36, p < .001, pr = .36.

Multivariate Lagged Analyses

The fixed-effects for the multivariate lagged analyses are presented in Table 1. For PTSD and OQ-IR, both cross-lagged effects (i.e., PTSD at Time t predicting OQ-IR at Time t + 1 when controlling for OQ-IR at Time t and linear and quadratic time, and vice-versa) were statistically significant, suggesting a reciprocal association between changes in PTSD symptoms and intimate relationship problems across treatment. The effect size estimates for these lagged effects were in the small to medium range. A similar reciprocal pattern emerged between PTSD and OQ-SR.

Table 1.

Fixed-Effect Estimates for the Multivariate Multilevel Lagged Analysis

| Outcome | Coefficient | b | SE | cr | p | pr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD Symptoms | ||||||

| Intercept | 35.56 | 3.38 | 10.53 | <.001 | .62 | |

| Time (linear) | −0.10 | 0.03 | −3.31 | .001 | .24 | |

| Time (quadratic) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | .914 | .01 | |

| Autocorrelation PTSD | 0.34 | 0.05 | 6.78 | .000 | .46 | |

| Cross-Lagged OQ-IR → PTSD | 0.22 | 0.09 | 2.53 | .011 | .19 | |

| Interpersonal Functioning Problems (OQ-IR) | ||||||

| Intercept | 15.57 | 1.81 | 8.62 | <.001 | .54 | |

| Time (linear) | −0.04 | 0.01 | −3.03 | <.001 | .22 | |

| Time (quadratic) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.24 | .810 | .02 | |

| Autocorrelation IFP | 0.21 | 0.06 | 3.52 | <.001 | .26 | |

| Cross-Lagged PTSD → OQ-IR | 0.05 | 0.02 | 2.11 | .04 | .16 | |

| Outcome | Coefficient | b | SE | cr | p | pr |

| PTSD Symptoms | ||||||

| Intercept | 34.19 | 3.47 | 9.86 | .000 | .60 | |

| Time (linear) | −0.10 | 0.03 | −3.17 | .002 | .23 | |

| Time (quadratic) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | .909 | .01 | |

| Autocorrelation PTSD | 0.38 | 0.05 | 7.16 | <.001 | .48 | |

| Cross-Lagged OQ-SR → PTSD | 0.21 | 0.10 | 2.18 | .030 | .16 | |

| Social Role Functioning (OQ-SR) | ||||||

| Intercept | 10.43 | 1.45 | 7.18 | <.001 | .48 | |

| Time (linear) | −0.03 | 0.01 | −2.15 | .03 | .16 | |

| Time (quadratic) | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | .99 | .00 | |

| Autocorrelation SR | 0.12 | 0.05 | 2.44 | .02 | .18 | |

| Cross-Lagged PTSD → OQ-SR | 0.06 | 0.02 | 3.08 | <.001 | 0.23 | |

Note: b = unstandardized coefficient, SE = Standard Error, cr = critical ratio (estimate/standard error, which follows a z-distribution), p = p-value, pr = partial regression coefficient (.10, .24, and .37 for small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively). PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder (as assessed by the PCL), IFP = interpersonal functioning problems (as assessed by the OQ questionnaire), OQ-SR = social role functioning (as assessed by the OQ questionnaire).

Moderators of Cross-Lagged Associations

Military status predicted one cross-lagged path: the path from OQ-SR to PTSD (b = −.35, t = −2.00, p = .045, pr = .16; all other ps > .114, all other prs < .13). Participants with a past or current military affiliation (active duty and veteran) exhibited a positive association between OQ-SR and subsequent PTSD levels (b = .39, t = 2.72, p = .006), while civilian participants did not exhibit a significant relationship between OQ-SR and subsequent PTSD levels (b = .04, t = .34, p = .733). In the context of overall decreasing PTSD levels, the positive association between OQ-SR and subsequent PTSD levels can be interpreted as higher levels of social role problems being associated with smaller decreases in PTSD from session to session, for military, but not civilian, participants. Gender did not moderate any of the cross-lagged paths in any model (PTSD-IR, PTSD-SR, all ps > .336, all prs < .08). Finally, none of the cross-lagged paths between PTSD symptoms and OQ-IR and between PTSD symptoms and OQ-SR significantly varied as a function of consultation condition (all ps > .25, all prs < .09), in other words, consultation condition did not impact the prospective associations between PTSD symptoms and both dimensions of social functioning.

Discussion

We used a series of multilevel regression models to examine the association between PTSD symptoms and interpersonal functioning problems, and PTSD and social role functioning problems during a course of CPT from multiple perspectives (i.e., within-subjects associations, correlation of change, lagged-influences). All results indicated a robust association between PTSD symptoms and interpersonal functioning problems, and PTSD and social role functioning problems during a course of CPT. Perhaps most notably, multivariate multilevel lagged analyses indicated a reciprocal relationship between PTSD and interpersonal functioning problems, and PTSD and social role functioning problems across time, such that higher levels of PTSD at one time point were associated with smaller subsequent decreases in both social functioning variables and poorer social functioning (as indicated by OQ-IR and OQ-SR scores, respectively) at one time point was associated with smaller subsequent decreases in PTSD. Finally, moderation analyses revealed that the temporal relationships between PTSD symptoms and social role functioning problems are reciprocal for those with military status, but not civilians.

The results of the current study build upon those of previous studies. For example, Evans et al.’s (2009) study provided support for the social causation hypothesis, such that baseline family functioning affected PTSD symptom levels at posttreatment and six-month follow-up, again highlighting the importance of adaptive social functioning. The current results partially corroborate this finding but suggest the relationship between PTSD symptoms and social functioning during CPT treatment is mostly reciprocal (Monson et al., 2009). Perhaps the difference in findings is due to differences in assessment time points, such that reciprocal relationships are best detected at the session level, highlighting the dynamic nature of social functioning and PTSD symptoms. Alternatively, it may be a difference in treatment modality, sample characteristics, or assessment of overall interpersonal functioning as opposed to specifically family functioning.

The reciprocal nature of the relationships between PTSD symptoms and interpersonal functioning problems, and between PTSD and social role functioning problems has several important implications for treatment. First, individually-delivered CPT decreased interpersonal problems and social role problems without adjunctive treatment focused specifically on social functioning, but problems in both social functioning variables remained elevated at the end of the 12-session protocol (Monson et al., 2018). It is possible that additional improvements in social functioning may require more time after PTSD recovery as individuals continue to use skills and insights gained during treatment to improve their social interactions and fulfillment of social roles. However, given that interpersonal problems and social role problems prospectively predicted changes in PTSD symptoms, treatments targeting PTSD symptoms and social functioning concomitantly may result in maximum benefit to clients. Relatedly, this highlights the importance of the social network and social relationships at work during trauma-focused treatment. While we hesitate to interpret null findings, the fact that gender was not a significant moderator of any path may suggest that increasing interpersonal functioning and social role functioning is equally as important for men in women in recovery from PTSD. Psychotherapies that include the immediate social context may be particularly beneficial for those experiencing posttraumatic stress (e.g. Berger & Weiss, 2009). For example, trauma-focused treatments that incorporate close significant others, such as Cognitive-Behavioral Conjoint Therapy (Monson, & Fredman, 2012), Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation (STAIR; Cloitre, Koenen, Cohen, & Han, 2002), and Structured Approach Therapy (SAT; Sautter, Armelie, Glynn, & Wielt, 2011) have been found to decrease trauma symptoms and increase relationship functioning for the client diagnosed with PTSD (Cloitre et al., 2010; Monson et al., 2012; Sautter, Glynn, Cretu, Senturk, & Vaught, 2015; Shnaider, Pukay-Martin, Fredman, Macdonald, & Monson, 2014). While CPT here effectively reduced PTSD symptoms and resulted in some improvements in both aspects of social functioning, treatments that explicitly target both may have a stronger impact.

Additionally, moderation analyses found that the temporal relationships between PTSD symptoms and social role functioning problems across CPT are reciprocal for those with military status, but not civilians. Specifically, reduction in PTSD symptoms predicted subsequent improvement in social role functioning for civilians, but the reverse was not true. This may suggest that improvements in social role functioning play a more central role in reducing PTSD symptoms for those with military affiliations. Social-cognitive theories of posttraumatic recovery suggest that self-efficacy plays a central role in recovery from posttraumatic symptoms (Benight & Bandura, 2004). Additionally, research has shown that perceived self-efficacy moderates the relationships between combat exposure and PTSD symptoms (Blackburn & Owen, 2015), and that increasing self-efficacy may decrease negative cognitions associated with PTSD for combat veterans (Brown et al., 2016). Relatedly, veterans may perceive improving social role functioning to be as important as or more important than reducing PTSD symptoms (Johnson et al., 1996; Zatzick et al., 2007). Taken together, it may be that for individuals who serve, or have served in the military, improving social role functioning is more centrally related to increasing self-efficacy, and subsequently decreasing PTSD symptoms. Perhaps this relationship is especially important for individuals still serving in the military when considering the need to function in the same workplace the trauma occurred. Future research should investigate the temporal relationships between social role functioning, self-efficacy, and PTSD symptoms directly.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

The trial from which the data were drawn focused on treatment effectiveness outside of controlled clinical research settings. This methodology establishes the feasibility of this treatment as an effective means of treating PTSD across many settings and with clients varying in age, gender, and military status in the real world. However, there are some limitations associated with increasing external validity. First, obtaining structured diagnostic interviews of patients across a wide geographic region was not feasible. Therefore, we relied on clinician diagnosis and a self-report measure with a cutoff score indicating probable PTSD for inclusion of patients. PTSD symptoms and social functioning were assessed using self-report questionnaires with demonstrated strong psychometric properties, however, patients completed both of these measures at the same time. This may have introduced common-method error variance (i.e., general improvements account for association). Additionally, the entire sample analyzed here met probable criteria for PTSD and agreed to be randomized to a consultation condition. Furthermore, pre-trauma social functioning was not assessed. As such, there was no comparison group in these analyses and pre-trauma social functioning was not accounted for. While the sample was diverse in regard to gender and military status, the sample was not diverse in regard to race or ethnicity, which may limit generalizability. Finally, the current study may have been underpowered to detect meaningful moderator variables. We did have enough power to identify military status as a statistically significant moderator with an effect size that was closer to small than medium (pr = .16; small effect size = .10 medium effect size = .24). The moderator analysis with the biggest effect size (pr = .08) that was not statistically significant was that of gender predicting the cross-lag from OQ-SR to PTSD. The pattern of observed p-values and corresponding effect sizes suggests that we had enough power to detect a moderator with a small-medium effect size. However, moderators with even a small effect sizes might be important, and future research with larger samples is necessary to fully explore moderators of the association between social and interpersonal functioning and PTSD during treatment.

To our knowledge this is one of the first studies to assess the temporal relationships between symptom reduction and social functioning during treatment in routine care settings. Additionally, this study assessed these relationships several ways, with the most nuanced being on a session-by-session basis. Furthermore, social functioning was assessed broadly, which may produce a more holistic assessment of how symptoms affect social behavior generally. Future research may focus on investigating functioning across different types of interpersonal relationships as it relates to PTSD symptoms. For example, social support of intimate partners at pretreatment has been found to predict greater decreases in PTSD symptoms across treatment (Shnaider, Sijercic, Wanklyn, Suvak, & Monson, 2017) and family or friends’ encouragement to face distress may reduce the likelihood of dropout (Meis et al., 2019). Assessing domains separately may produce findings that suggest certain relationships are more impactful for PTSD treatment than others.

Moreover, the generalizability of the current study’s findings is bolstered by the use of a sample that is about half female and just under half military/Veteran. Future research could shed more light on the relationship between PTSD symptoms and social functioning during the course of treatment by: 1) examining these associations across several types of treatment that put different emphasis on the degree to which they target PTSD symptoms and social functioning, 2) including collateral reports of social functioning from friends or family, and 3) implementing a design in which semi-structured interviews to assess PTSD and social functioning could be administered several times throughout treatment. Overall, these findings suggest that social functioning is an important outcome and mechanism of symptom reduction during CPT treatment for PTSD.

Social functioning is robustly related to PTSD symptoms throughout treatment

Social functioning problem reduction predicts subsequent PTSD symptom reduction

PTSD symptom reduction predicts subsequent social functioning problem reduction

Social role functioning problems only predict PTSD symptoms for military status

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant [259353], and work on this paper by the third author was supported by NIH grant T32 DA019426.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Two patients did not have clinician-diagnosed PTSD, but had a PCL-IV (Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993) score above the cut-off (50) and the clinicians believed that treatment would be indicated.

References

- Brown A, Kouri NA, Rahman N, Joscelyne A, Bryant RA, & Marmar CR (2016). Enhancing self-efficacy improves episodic future thinking and social-decision making in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Research, 242, 19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.05.02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). (1987). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin SA, Imel ZE, Braithwaite SR, & Atkins DC (2014). Analyzing multiple outcomes in clinical research using multivariate multilevel models. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52(5), 920–930. doi: 10.1037/a0035628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead DJ, Hatch AL, Lambert MJ, Eggett DL, Goates MK, & Vermeersch DA (2003). Clinical significance of the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2). The Behavior Analyst Today, 4, 86–97. doi: 10.1037/h0100015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benight CC, & Bandura A (2004). Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(10), 1129–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger R, & Weiss T (2009). The Posttraumatic Growth model: An expansion to the family system. Traumatology, 15(1), 63–74. doi: 10.1177/1534765608323499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn L, & Owens GP (2015). The effect of self efficacy and meaning in life on posttraumatic stress disorder and depression severity among veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(3), 219–228. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosc M (2000). Assessment of social functioning in depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 41, 63–69. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(00)90133-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragdon RA, & Lombardo TW (2012). Written disclosure treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in substance use disorder inpatients. Behavior Modification, 36(6), 875–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter SP, DiMauro J, Renshaw KD, Curby TW, Babson KA, & Bonn-Miller MO (2016). Longitudinal associations of friend-based social support and PTSD symptomatology during a cannabis cessation attempt. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 38, 62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Koenen KC, Cohen LR, & Han H (2002). Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: a phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 1067–1074. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.5.1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Stovall-McClough KC, Nooner K, Zorbas P, Cherry S, Jackson CL, … Petkova E (2010). Treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse: a randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(8), 915–924. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creech SK, Benzer JK, Liebsack BK, Proctor S, & Taft CT (2013). Impact of coping style and PTSD on family functioning after deployment in Operation Desert Shield/Storm returnees. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(4), 507–511. doi: 10.1002/jts.21823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbes CR, Kaler ME, Schult T, Polusy MA, & Arbisis PA (2011). Mental health diagnosis and occupational functioning in National Guard/Reserve veterans returning from Iraw. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development, 48 (10, 1159–1170. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2010.11.0212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans L, Cowlishaw S, & Hopwood M (2009). Family functioning predicts outcomes for veterans in treatment for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(4), 531–539. doi: 10.1037/a0015877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, Rauch SAM, Riggs DS, Feeny NC, & Yadin E (2005). Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: outcome at academic and community clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 953–964. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock C, Ellis AA, Williamson P, & Nixon RDV (2015). The prospective role of cognitive appraisals and social support in predicting children’s posttraumatic stress. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(8), 1485–1492. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0034-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DR, Rosenheck R, Fontana A, Lubin H, Charmey D, & Southwick S Outcome of intensive inpatient treatment for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 753(6), 771–777. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.6.771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM, Williams WH, Jetten J, Haslam SA, Harris A, & Gleibs IH (2012). The role of psychological symptoms and social group memberships in the development of post-traumatic stress after traumatic injury. British Journal of Health Psychology, 17(4), 798–811. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02074.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K, & Norris FH (2008). Longitudinal linkages between perceived social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms: sequential roles of social causation and social selection. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(3), 274–281. doi: 10.1002/jts.20334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DW, Taft C, King LA, Hammond C, & Stone ER (2006). Directionality of the association between social support and posttraumatic stress disorder: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(12), 2980–2992. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00138.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk RE (1996). Practical significance: A concept whose time has come. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 56(5), 746–759. doi: 10.1177/0013164496056005002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen KC, Stellman JM, Stellman SD, & Sommer JF (2003). Risk factors for course of posttraumatic stress disorder among Vietnam veterans: a 14-year follow-up of American Legionnaires. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(6), 980–986. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffaye C, Cavella S, Drescher K, & Rosen C (2008). Relationships among PTSD symptoms, social support, and support source in veterans with chronic PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(4), 394–401. doi: 10.1002/jts.20348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ, Burlingame GM, Umphress V, Hansen NB, Vermeersch DA, Clouse GC, & Yanchar SC (1996a). The reliability and validity of the Outcome Questionnaire. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 5(4), 249–258. doi: 10.2466/02.08.PR0.112.3.689-693 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ, Gregersen AT, & Burlingame GM (2004a). The Outcome Questionnaire-45 In Maruish ME (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: Instruments for adults (pp. 191–234). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ, Morton JJ, Hatfield DR, Harmon C, Hamilton S, Shimokawa K, … Burlingame GB (2004b). Administration and scoring manual for the OQ-45.2 (Outcome Ques-tionnaire) (3rd ed.). Wilmington, DE: American Professional Credentialling Services LLC [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ, Hansen NB, Umphress V, Lunnen K, Okiishi J, Burlingame GM, et al. (1996b). Administration and scoring manual for the OO-45.2. Stevenson, MD: American Professional Credentialing Services LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald A, Monson CM, Doron-Lamarca S, Resick PA, & Palfai TP (2011). Identifying patterns of symptom change during a randomized controlled trial of cognitive processing therapy for military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of traumatic stress, 24(3), 268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, DuHamel K, Nereo N, Ostroff J, Parsons S, Martini R, … Redd WH (2002). Predictors of PTSD in mothers of children undergoing bone marrow transplantation: the role of cognitive and social processes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(7), 607–617. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.7.607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meis LA, Noorbaloochi S, Hagel Campbell EM, Erbes CR, Polusny MA, Velasquez TL, … Spoont MR (2019). Sticking it out in trauma-focused treatment for PTSD: It takes a village. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(2), 246–256. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, & Fredman SJ (2015). Cognitive-behavioral couple therapy for PTSD In Gurman A, Lebow J, & Snyder DK (Eds.), Clinical handbook of couple therapy (pp. 531–554). New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Fredman SJ, Macdonald A, Pukay-Martin ND, Resick PA, & Schnurr PP (2012). Effect of Cognitive-Behavioral Couple Therapy for PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 308(7), 700–709. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Shields N, Suvak MK, Lane JEM, Shnaider P, Landy MSH, … Stirman SW (2018). A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of training strategies in cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: Impact on patient outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 110, 31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Taft CT, & Fredman SJ (2009). Military-related PTSD and intimate relationships: From description to theory-driven research and intervention development. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén BO (1998-2012). Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Perry S, Difede J, Musngi G, Frances AJ, & Jacobsberg L (1992). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder after burn injury. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 149(7), 931–935. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.7.931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw KD, Campbell SB, Meis L, & Erbes C (2014). Gender differences in the associations of PTSD symptom clusters with relationship distress in U.S. Vietnam Veterans and their partners. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(3), 283–290. doi: 10.1002/jts.21916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Monson CM, & Chard KM (2017). Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD: A comprehensive manual. New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robinaugh DJ, Marques L, Traeger LN, Marks EH, Sung SC, Gayle Beck J, … Simon NM (2011). Understanding the relationship of perceived social support to posttrauma cognitions and post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(8), 1072–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sautter FJ, Armelie AP, Glynn SM, & Wielt DB (2011). The development of a couple-based treatment for PTSD in returning veterans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(1), 63–69. doi: 10.1037/a0022323 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sautter FJ, Glynn SM, Cretu JB, Senturk D, & Vaught AS (2015). Efficacy of structured approach therapy in reducing PTSD in returning veterans: A randomized clinical trial. Psychological Services, 12(3), 199–212. doi: 10.1037/ser0000032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shallcross LJ, Freemantle N, Nisar S, & Ray D (2016). A cross-sectional study of blood cultures and antibiotic use in patients admitted from the Emergency Department: missed opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. BMC Infectious Diseases, 16(1), 166. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1515-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shnaider P, Pukay-Martin ND, Fredman SJ, Macdonald A, & Monson CM (2014). Effects of Cognitive-Behavioral Conjoint Therapy for PTSD on partners’ psychological functioning. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(2), 129–136. doi: 10.1002/jts.21893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shnaider P, Sijercic I, Wanklyn SG, Suvak MK, & Monson CM (2017). The Role of social support in Cognitive-Behavioral Conjoint Therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Therapy, 48(3), 285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BN, Taverna EC, Fox AB, Schnurr PP, Matteo RA, & Vogt D (2017). The role of PTSD, depression, and alcohol misuse symptom severity in linking deployment stressor exposure and post military work and family outcomes in male and female Veterans. Clinical Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 5(4), 664–682. doi: 10.1177/2167702617705672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Z, & Mikulincer M (2007). Posttraumatic intrusion, avoidance, and social functioning: A 20-year longitudinal study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(2), 316–324. doi 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirman S, Shields N, Deloriea J, Landy MS, Belus JM, Maslej MM, & Monson CM (2013). A randomized controlled dismantling trial of post-workshop consultation strategies to increase effectiveness and fidelity to an evidence-based psychotherapy for Posttraumatic stress disorder. Implementation Science, 8(1), 82. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvak MK, Walling SM, Iverson KM, Taft CT, & Resick PA (2009). Multilevel regression analyses to investigate the relationship between two variables over time: Examining the longitudinal association between intrusion and avoidance. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(6), 622–631. doi: 10.1002/jts.20476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Schumm JA, Panuzio J, & Proctor SP (2008). An examination of family adjustment among Operation Desert Storm veterans. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 648–656. doi: 10.1037/a0012576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Watkins LE, Stafford J, Street AE, & Monson CM (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder and intimate relationship problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(1), 22–33. doi: 10.1037/a0022196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Wald J, & Asmundson JG (2006). Factors associated with occupational impairment in people seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 25(2), 289–301. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2006-0026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeersch DA, Lambert MJ, & Burlingame GM (2000). Outcome Questionnaire: Sensitivity to change. Journal of Personality Assessment, 24(2), 242–261. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7402_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeersch DA, Whipple JL, Lambert MJ, Hawkins EJ, Burchfield CM, & Okiishi JC (2004). Outcome Questionnaire: Is it sensitive to changes in counseling center clients? Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(1), 38–49. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.51.1.38 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt D, Smith BN, Fox AB, Amoroso T, Tavema E, & Schnurr PP (2017). Consequences of PTSD for the work and family quality of life of female and male U.S. Afghanistan and Iraq War veterans. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(3), 341–352. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1321-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachen JS, Jimenez S, Smith K, & Resick PA (2014). Long-term functional outcomes of women receiving cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(Suppl 1), S58–S65. doi: 10.1037/a0035741 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AC, Monson CM, & Hart TL (2016). Understanding social factors in the context of trauma: Implications for measurement and intervention. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 25(8), 831–853. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2016.1152341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, Huska J, & Keane T (October 1993). The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, Validity, and Diagnostic Utility. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins KC, Lang AJ, & Norman SB (2011). Synthesis of the psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) military, civilian, and specific versions. Depression and Anxiety, 25(7), 596–606. doi: 10.1002/da.20837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalta AK, Gillihan SJ, Fisher AJ, Mintz J, McLean CP, Yehuda R, & Foa EB (2014). Change in negative cognitions associated with PTSD predicts symptom reduction in prolonged exposure. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(1), 171–175. doi: 10.1037/a0034735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatzick DF, Russo J, Rajotte R, Uehara R, Roy-Byrne P, Ghesquiere A, Jurkovich G, & Rivera F (2007). Strengthening the patient-provider relationship in the aftermath of physical trauma through an understanding of the nature and severity of posttraumatic concerns. Psychiatry, 70(3), 260–273. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2007.70.3.260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerach G, Solomon Z, Horesh D, & Ein-Dor T (2013). Family cohesion and posttraumatic intrusion and avoidance among war veterans: a 20-year longitudinal study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(2), 205–214. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0541-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]