Abstract

Objective

Postoperative neurocognitive disorder (PND) is a main complication that is commonly seen postoperatively in elderly patients. The underlying mechanism remains unclear, although neuroinflammation has been increasingly observed in PND. Atorvastatin is a pleiotropic agent with proven anti-inflammatory effects. In this study, we investigated the effects of atorvastatin on a PND mouse model after peripheral surgery.

Material and methods

The mice were randomized into five groups. The PND models were established, and an open field test and fear condition test were performed. Hippocampal inflammatory cytokine expression was determined using ELISA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) expression in the hippocampus was tested using qRT-PCR and western blot analysis.

Results

On day 1 after surgery, inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-6 showed a significant increase in the hippocampus, with prominent cognitive impairment. Atorvastatin treatment improved cognitive function in the mouse model, attenuated neuroinflammation, and increased PPARγ expression in the hippocampus. However, treatment with the PPARγ antagonist GW9662 partially reversed the protective effects of atorvastatin.

Conclusions

These results indicated that atorvastatin improves several hippocampal functions and alleviates inflammation in PND mice after surgery, probably through a PPARγ-involved signaling pathway.

Keywords: Postoperative neurocognitive disorder, atorvastatin, inflammation, PPARγ, hippocampal functions, neuroinflammation, cognitive impairment

Introduction

Postoperative neurocognitive disorder (PND) is a newly defined dysfunction that comprises cognitive impairment and a decline in elderly patients after anesthesia and surgery.1 The incidence of PND is about 30% at 24 to 72 hours after undergoing major non-cardiovascular surgery in patients aged over 65 years based on a recent Chinese study.2 Currently, PND has become the focus of studies because of its clinical consequences, although its precise mechanism remains unknown. Therefore, investigating the pathophysiology and the underlying mechanism of PND might contribute to delivering a more efficacious preventive and treatment strategy for this cognitive disorder.

Neuroinflammation plays a critical role in PND development and progression.3 The enhanced inflammatory responses might cause a severe clinical impact on the brain, including cognitive dysfunction. Based on an animal experiment, the neuroinflammatory response showed a correlation with PND occurrence, which might result from surgery-induced suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines that attenuate cognitive dysfunction.4 Moreover, clinical studies have also demonstrated that the inflammatory cytokine levels in PND patients after surgery were significantly higher compared with those without PND.5 Based on these results, we hypothesized that pharmacological inhibition of neuroinflammation is important for treating and preventing postoperative cognitive impairment.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) is a multifunctional nuclear hormone receptor, which mainly focuses on regulation of inflammation, oxidative metabolism, lipid metabolism, and glucose homeostasis.6 Recent evidence indicated that PPARγ agonists alleviate and even prevent neuroinflammatory responses.7 This is supported by the results that PPARγ activators protect neurofunction in a group of neurological degenerative disorders by regulating the inflammatory responses.8

Statins are first-line lipid-lowering drugs and PPARγ agonists. Evidence has shown that atorvastatin, which is the most widely used statin, exerts pleiotropic effects by inhibiting cell proliferation, improving endothelial function, and reducing inflammation by activating the PPARγ signaling pathway.9 However, whether atorvastatin prevents or protects PND remains controversial. Therefore, this animal study was designed to determine the effects of atorvastatin on PND mouse models.

Material and methods

Animals

This study was approved by the animal ethics committee at Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital, Capital Medical University, and was conducted in accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” that was published by the National Institutes of Health, to minimize animal suffering and the number of animals used in the experiments.

Male C57BL/6 mice (Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) aged 28 to 30 weeks and weighing 30 to 38 g were chosen for this study. The animals were maintained at room temperature at 25°C at a relative humidity of 55% under a 12-hour:12-hour light–dark cycle with free access to food and water. The animals were randomly assigned to one of the following five groups (n = 8 mice per group): group A was the sham-operated group (negative control); group B was the PND group; group C was the atorvastatin-treated sham-operated group; group D was the PND group with atorvastatin treatment; and group E was the PND group with atorvastatin and GW9662 treatment.

Reagents and PND model

The mice in groups A and C were given placebo (0.3 mL of 0.9% saline), and mice in groups B, D, and E received 400 μg of atorvastatin (Pfizer, New York, NY, USA) in 0.3 mL of 0.9% saline that was administered for 7 consecutive days by gavage. A PPARγ antagonist GW9662 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was dissolved in 50% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then diluted in saline (final concentration of DMSO: 0.5%), and it was intraperitoneally administered at a dose of 2 mg/kg to mice in group E. The atorvastatin dose of 10 mg/kg was chosen for short-term treatment, which triggered robust anti-inflammatory activity at this dose.10 The mice in groups B, D, and E underwent orthopedic surgery, while those in groups A and C underwent a sham operation. All mice in the groups underwent two behavioral tests (open field test [OFT] and fear condition test [FCT]) on day 1 after surgery or sham operation. After euthanasia, hippocampal tissue was removed and immediately stored in liquid nitrogen at −80°C for further examination.

The PND models were created based on our previous report.11 Briefly, mice in groups B, D, and E were anesthetized initially with 2% isoflurane (Baxter International, Inc., Deerfield, IL, USA) to induce anesthesia, followed by 1.5% isoflurane (Baxter International, Inc.) for anesthesia maintenance. After disinfecting the left hind paws three times using povidone–iodine, a longitudinal incision was made using a scalpel on each paw. Following each incision, a 0.38-mm pin was inserted at the tibial medullary canal. After the periosteum was stripped, osteotomy and irrigation were performed, and the wound was closed using 4-0 nylon sutures after injecting 0.25% ropivacaine subcutaneously (Astra Zeneca, Wilmington, DE, USA). For sham-operated mice in groups A and C, the procedure was conducted as described above but the pin was not inserted into the tibia. The body temperature of the mice was maintained at 37.0°C using a heating pad. The mice were allowed to naturally awaken in an incubator at 37.0°C, and they were then returned to their cages. At the end of the experiment, all mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized by transcardial perfusion with normal saline. Hippocampal tissues were separated and stored at −80°C for further detection.

Behavioral tests: OFT and FCT

The OFT was used to evaluate the locomotor activities and anxiety of the experimental mice.12 On day 1 after surgery, the mice were directly each placed in the center of an open field (50 cm × 50 cm × 38 cm, length × width × height). The movements of each mouse were then recorded using a digital camera during a 5-minute testing session. The general locomotor activity (the total distance that the mouse moved in an open field), number of rearings (frequency that the mouse stood on its hind legs in the open field), and center square duration (the time spent by each mouse in the central square) were recorded.

The FCT has been extensively used to determine the surgical effects on the memory of experimental mice.13 Briefly, all the mice underwent FCT training 1 day before the surgery. After a 3-minute exploration period, three pairs of sound stimuli (2000 Hz and 90 Db for 30 seconds each) and electric shock stimuli (1 mA, 2 seconds) were given to the mice. The interval between the two pairs of stimuli was 1 minute. On day 1 after the surgery, a context test and a cue test were conducted for each mouse. The mice that underwent the context test were placed in the same context as the pre-surgical training for a 5-minute observation period without stimulation by sound or electric shock, and the freezing times (the time of immobility that small rodents tend to present when faced with fear) for the mice were recorded. After finishing the 2-hour context test, the cue test was performed. After a 3-minute exploration period, the mice underwent sound stimuli (2000 Hz and 90 Db for 30 seconds each) without an electric shock stimulus, and the freezing times of mice for the cue test were recorded. A camera-based monitoring system (XeyeFcs System, Beijing Macro Ambition S&T Development Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was used to automatically record and calculate the freezing times of the mice when conducting these tests.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

After completing the behavioral tests, the mice were sacrificed as described above, and the hippocampal tissues were separated, homogenized, and stored at −80°C before use. Next, protein quantification was conducted using bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). The hippocampal proinflammatory cytokine levels, including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The inflammatory mediators in the tissue were expressed as ng/g of tissue. A spectrophotometer was used to measure the color intensity by absorbance at a wavelength of 495 nm. The sensitivity applied in this study was 0.05 pg/mL.

Quantitative real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

In accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, total RNA from all the hippocampal tissues was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). A reverse-transcription reaction was conducted to generate cDNA (PrimeScript® RT reagent kit, Takara Biotechnology [Dalian] Ltd., Dalian, China). The primers, which were designed using Primer 5.0 software (PREMIER Biosoft International, San Francisco, CA, USA), were as follows:

Mouse PPARγ, Forward: 5ʹ-GAGTAGCCTGGGCTGCTTTT-3′;

Reverse: 5ʹ-ATAATAAGGCGGGGACGCAG-3′;

Mouse β-actin, Forward: 5ʹ-AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC-3′;

Reverse: 5ʹ-CAGGAAGGAAGGCTGGAAG-3′.

Quantitative real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reactions (qRT-PCRs) with SYBR Green detection for PPARγ and β-actin gene expression were used (SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II, Takara Biotechnology [Dalian] Ltd.) on an ABI 7500 RT-PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The Ct method was used to analyze the results by calculating 2-ΔΔCt using the following formula: ΔCt = target gene Ct value −glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) Ct value and ΔΔCt = ΔCt treatment − ΔCt control.

Western blot analyses

On day 1 after surgery, the mouse hippocampal tissues were separated, homogenized, and stored at −80°C before use. Protein quantification was conducted using a BCA assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). The collected protein samples were separated with sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The gel was then transferred into a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane and incubated with an anti-PPARγ primary antibody (1:1000, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA) overnight. Based on the individual experiments, anti-β actin (1:1000, Abcam Inc.) antibodies were used as loading controls. The goat anti-rabbit/anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG was added as a secondary antibody (1:2500, Zhongshan Goldenbridge Inc., Beijing, China) and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. An enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) was used to test the target proteins in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The pictures were then obtained, and the gray values for each target protein were analyzed using an Alpha EaseFC imaging system (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows version 20.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The values of multiple groups were compared using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Fisher’s least significant difference test was used for two-way comparisons. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Behavioral assessment

To determine if major surgery impairs cognitive function, behavioral assessment with FCT and OFT was performed in adult mice after surgery.

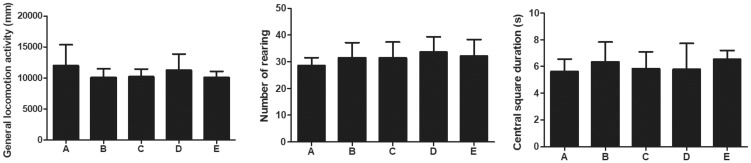

For the OFT test, there were no differences in the total distance traveled, time spent at the center of the arena, or the number of rearings among the groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Open field test of mice in each group. The general locomotor activity (mm), number of rearings, and center square duration (s) were counted, respectively.

Group A: Sham, group B: PND, group C: Atorvastatin, group D: PND + atorvatastin, group E: PND +atorvastatin + GW9662.

PND, postoperative neurocognitive disorder.

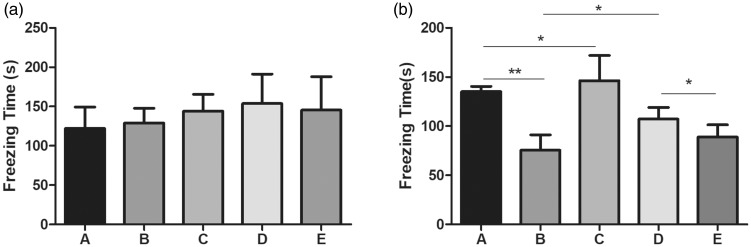

For the FCT test, the freezing time for the context test on day 1 after surgery showed no significant differences (Figure 2a). In the cue test, the freezing time of PND mice in group B was significantly shorter compared with the sham-operated mice in group A (Figure 2b, p < 0.01). Compared with group B, the freezing time was significantly increased after treatment with atorvastatin in group D (Figure 2b, p < 0.05), and a significant down-regulation was observed after adding GW9662 (group E) (Figure 2b, p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Fear condition test of mice in each group.

a. The freezing time that was recorded from the context test in each group; b. The freezing time that was recorded from the cue test in each group.

Group A: Sham, group B: PND, group C: Atorvastatin, group D: PND + atorvatastin, group E: PND + atorvastatin + GW9662.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, respectively.

PND, postoperative neurocognitive disorder.

These findings indicate that atorvastatin preserved learning and memory after surgery, and that atorvastatin protects against orthopedic surgery-induced cognitive impairment on day 1 after surgery in mice.

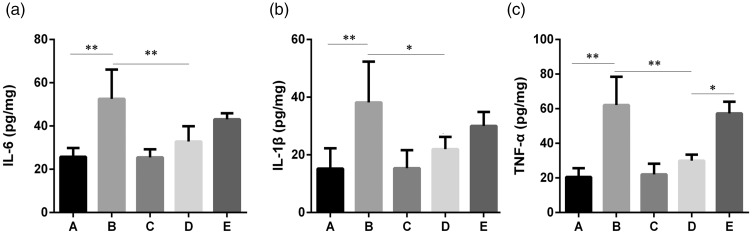

Analysis of inflammatory cytokines: IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α

As shown in Figure 3, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α levels showed a significant increase in group B compared with group A (p < 0.01). After administering atorvastatin (group C) in the normal mice, no significant difference was observed in IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α levels in the hippocampal brain tissue compared with group A. Compared with group B, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α levels were markedly down-regulated after atorvastatin injection (group D). After treatment with GW9662 (group E), an up-regulated trend was observed in all the detected inflammatory cytokines compared with group B, but only TNF-α showed a statistical significance (Figure 3c, p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Expression levels of IL-6 (a) and IL-1β (b) and TNF-α (c) in the hippocampal brain tissue of each group. One-way ANOVA was used for data analysis, and the error line represents the SD.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, respectively.

Group A: Sham, group B: PND, group C: Atorvastatin, group D: PND + atorvatastin, group E: PND +atorvastatin + GW9662.

PND, postoperative neurocognitive disorder; IL-6, interleukin-2; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; ANOVA, analysis of variance; SD, standard deviation.

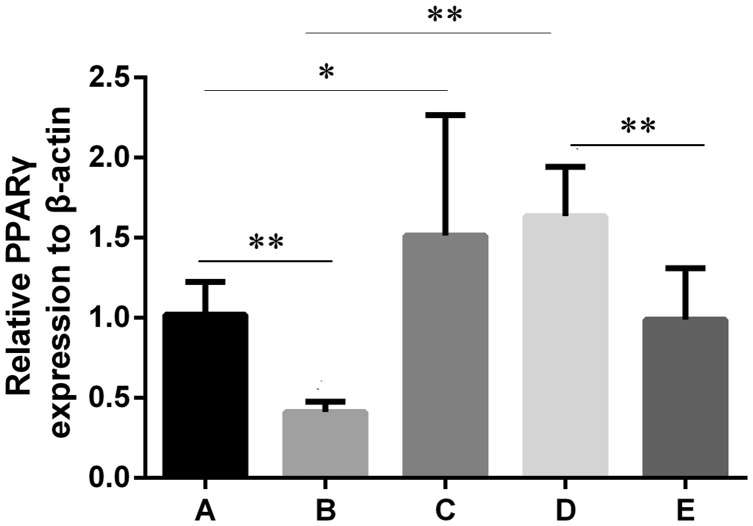

Results of qRT-PCR analysis

To study the correlation between the PND model group and PPARγ expression, animal modeling was conducted at the mouse level, and PPARγ mRNA expression was detected using qRT-PCR.

As shown in Figure 4, PPARγ mRNA expression in group B was significantly lower compared with group A (p < 0.01). After treating normal mice with atorvastatin (group C), a significant difference was observed in the PPARγ mRNA level in the hippocampal brain tissue compared with group A (p < 0.05). Compared with group B, the PPARγ mRNA level was significantly up-regulated after atorvastatin treatment (group D, p < 0.01), and significantly down-regulated after adding GW9662 (group E, p < 0.01).

Figure 4.

PPARγ mRNA expression levels in hippocampal brain tissue in each group. One-way ANOVA was used for data analysis, and the error line represents SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, respectively.

Group A: Sham, group B: PND, group C: Atorvastatin, group D: PND + atorvatastin, group E: PND + atorvastatin + GW9662.

PND, postoperative neurocognitive disorder; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma; ANOVA, analysis of variance; SD, standard deviation.

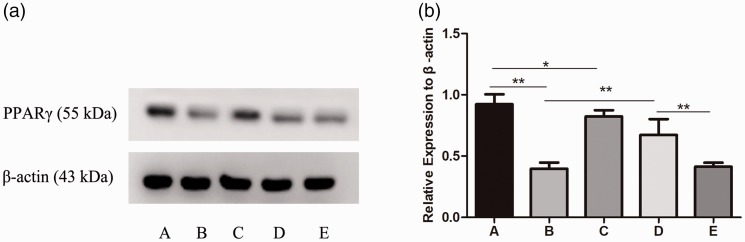

Results of western blot analysis

To further explore the correlation between PPAR and PND and mouse hippocampal inflammatory signaling pathways, western blotting was conducted to detect the molecular mechanism of atorvastatin in the hippocampal tissues of mice in each group.

As shown in Figure 5, the PPARγ mRNA expression level was consistent with that of the PPARγ protein level in group B, but it was significantly lower compared with group A (p < 0.01). After treating normal mice with atorvastatin, PPARγ protein levels were increased in the hippocampal brain tissue in group C compared with group A (p < 0.05). Compared with group B, PPARγ protein levels showed significant up-regulation after atorvastatin treatment (group D, p < 0.01), and significant down-regulation after adding GW9662 (group E, p < 0.01).

Figure 5.

PPARγ protein expression levels in the hippocampal brain tissues of each group. One-way ANOVA was used for data analysis, and the error line represents SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, respectively.

Group A: Sham, group B: PND, group C: Atorvastatin, group D: PND + atorvatastin, group E: PND + atorvastatin + GW9662.

PND, postoperative neurocognitive disorder; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma; ANOVA, analysis of variance; SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

In this study, our results demonstrated that atorvastatin treatment before surgery exerted a prominent protective effect from cognitive dysfunction after surgery in a mouse model. Consistent with the neurofunctional improvement, there was also a significant reduction in the levels of inflammatory factors such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α in the hippocampus, which is probably mediated by atorvastatin-induced upregulation of PPARγ.

In the OFT test, all mice in the groups showed no differences in general locomotor activity, center square duration, or number of rearings, which suggests that neither the orthopedic surgery nor atorvastatin administration affected the locomotor function and anxiety in the tested mice. After OFT, FCT including the context and cue tests was performed. The aim of FCT was to investigate the ability of mice to learn an associative memory between environmental cues and adverse experiences such as electric shock, which has become a standard way to assess hippocampal-dependent learning and memory in PND models.14 The freezing time was shorter in the PND group compared with the sham-operated group in the context test, which indicated that the mice in the PND group had learning and memory dysfunctions after surgery. Moreover, atorvastatin prolonged the freezing time of mice in the atorvastatin-treated group compared with the PND group, and this effect could be blocked by a PPARγ antagonist, which suggested that atorvastatin likely improved the cognitive function in mice through PPARγ regulation.

In the current study, proinflammatory factor levels (IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α) were prominently increased in the hippocampus on day 1 post-operation with a gross cognitive inhibition, suggesting that an acute elevation of cytokines might trigger a significant influence on the cognitive function. Atorvastatin prevents inflammation in the hippocampus in a variety of animal studies.15,16 Our results also confirmed that atorvastatin administration significantly alleviated hippocampal inflammation in mice. Although the precise mechanisms of its metabolism in the brain remains to be investigated, atorvastatin is easily transferred from the blood–brain barrier and penetrated deep into the phospholipid bilayer of cell membranes of the neurons, indicating the underlying mechanism of this agent in brain protection. The PPARγ antagonist GW9662 (i.e., in the GW9662-treated group), showed a significant reversal in only the TNF-α level, but not in IL-6 and IL-1β levels compared with the atorvastatin-treated group. This finding might suggest a complexity in regulating hippocampal inflammation because previous reports have indicated the involvement of other signaling pathways such as nuclear factor (NF)-κB17 or MAPK18 in neuronal inflammatory responses.

Our results also suggested that decreased hippocampal PPARγ might be a mechanism that is involved in neuroinflammation and subsequent cognitive dysfunction in this animal PND model. Specifically, atorvastatin administration, a PPARγ agonist, inhibited neuroinflammation and repaired cognitive function after surgery. Moreover, a PPARγ antagonist, GW9662, partially blocked the protective effect of atorvastatin. Therefore, we speculated that the preventive effects of atorvastatin in this study mainly occur through the PPARγ receptor.

PPARγ is the most extensively studied isoform of the PPAR family, and it has promising neuroprotective effects in various animal models of neurodysfunction. PPARγ agonists such as atorvastatin or pioglitazone are widely used in clinical medicine and animal studies. In an animal model of Parkinson’s disease, PPARγ agonists are shown to attenuate neuroinflammation, and improve memory and learning functions.19 Additionally, the PPARγ activation reduces the inflammatory response in autoimmune encephalomyelitis animal models, improving the clinical severity of this disease.20 However, neuroinflammation worsened when PPARγ expression was reduced in a seipin knockout mouse model.21 Consistent with these findings, our study demonstrated that surgery induced a gross decrease in hippocampal PPARγ expression, which was consistent with recent findings of PPARγ changes after PND.7 Because the PPARγ antagonist GW9662 counteracts the protective effects of atorvastatin, the PPARγ receptor was considered to be a therapeutic target for PND.

There are several limitations in this study. First, the mouse models do not completely mimic the behavioral impairment of PND such as delirium or language dysfunctions in humans. Therefore, whether PPARγ activation improves these disorders remains unknown. Second, although PPARγ activation induces anti-inflammatory effects in the brain, as shown in our study and other studies8,22 that investigated neuro-dysfunction, our results showed a trend toward a protective effect of atorvastatin on inflammatory factors from circulatory immune cells, which may be because PPARγ receptors are also expressed in monocytes and macrophages. Moreover, additional unknown mechanisms might be involved in cognitive protection by atorvastatin, expect for PPARγ. Therefore, further studies are required to more fully understanding the precise mechanisms of atorvastatin and its associated PPARγ expression and activation in PND.

In conclusion, the current study indicated that atorvastatin prevented cognitive dysfunction and alleviated several inflammatory responses in a mouse model of PND, which may occur via activation of the hippocampal PPARγ signaling pathway. Our study provided evidence that atorvastatin and its associated PPARγ activation might induce supplementary prevention and represent a therapeutic target for PND.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Contributions

YYN performed the experiments, collected the data, and wrote the manuscript. WCW, LJH, MDX, XC, and LDD contributed to collecting the data and reviewing the manuscript. WAS conceived the study and contributed to reviewing/editing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors declare that the study is sponsored by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81771139).

ORCID iD

References

- 1.Lv ZT, Huang JM, Zhang JM, et al. Effect of ulinastatin in the treatment of postoperative cognitive dysfunction: Review of current literature. Biomed Res Int 2016; 2016: 2571080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y, Liu X, Li H. [Incidence of the post-operative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients with general anesthesia combined with epidural anesthesia and patient-controlled epidural analgesia]. Zhong Nan Da Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2016; 41: 846–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu X, Yu Y, Zhu S. Inflammatory markers in postoperative delirium (POD) and cognitive dysfunction (POCD): A meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0195659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Z, Liu F, Ma H, et al. Age exacerbates surgery-induced cognitive impairment and neuroinflammation in Sprague-Dawley rats: The role of IL-4. Brain Res 2017; 1665: 65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu YZ, Yao R, Zhang Z, et al. Parecoxib prevents early postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: A double-blind, randomized clinical consort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95: e4082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamas Bervejillo M, Ferreira AM. Understanding peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: From the structure to the regulatory actions on metabolism. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019; 1127: 39–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Z, Yuan H, Zhao H, et al. PPARgamma activation ameliorates postoperative cognitive decline probably through suppressing hippocampal neuroinflammation in aged mice. Int Immunopharmacol 2017; 43: 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai W, Yang T, Liu H, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma): A master gatekeeper in CNS injury and repair. Prog Neurobiol 2018; 163–164: 27–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han L, Li M, Liu Y, et al. Atorvastatin may delay cardiac aging by upregulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in rats. Pharmacology 2012; 89: 74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Souza-Costa DC, Sandrim VC, Lopes LF, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of atorvastatin: Modulation by the T-786C polymorphism in the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene. Atherosclerosis 2007; 193: 438–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei C, Luo T, Zou S, et al. Differentially expressed lncRNAs and miRNAs with associated ceRNA networks in aged mice with postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 55901–55914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prut L, Belzung C. The open field as a paradigm to measure the effects of drugs on anxiety-like behaviors: A review. Eur J Pharmacol 2003; 463: 3–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laxmi TR, Stork O, Pape HC. Generalisation of conditioned fear and its behavioural expression in mice. Behav Brain Res 2003; 145: 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broadbent NJ, Gaskin S, Squire LR, et al. Object recognition memory and the rodent hippocampus. Learn Mem 2010; 17: 5–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke RM, Lyons A, O’Connell F, et al. A pivotal role for interleukin-4 in atorvastatin-associated neuroprotection in rat brain. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 1808–1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JK, Won JS, Singh AK, et al. Statin inhibits kainic acid-induced seizure and associated inflammation and hippocampal cell death. Neurosci Lett 2008; 440: 260–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang HK, Yan H, Wang K, et al. Dynamic regulation effect of long non-coding RNA-UCA1 on NF-kB in hippocampus of epilepsy rats. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2017; 21: 3113–3119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porto RR, Dutra FD, Crestani AP, et al. HSP70 facilitates memory consolidation of fear conditioning through MAPK pathway in the hippocampus. Neuroscience 2018; 375: 108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lecca D, Nevin DK, Mulas G, et al. Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties of a novel non-thiazolidinedione PPARgamma agonist in vitro and in MPTP-treated mice. Neuroscience 2015; 302: 23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiri-Shahsavar MR, Mirshafiee A, Parastouei K, et al. A novel combination of docosahexaenoic acid, all-trans retinoic acid, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 reduces T-bet gene expression, serum interferon gamma, and clinical scores but promotes PPARgamma gene expression in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Mol Neurosci 2016; 60: 498–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian Y, Yin J, Hong J, et al. Neuronal seipin knockout facilitates Abeta-induced neuroinflammation and neurotoxicity via reduction of PPARgamma in hippocampus of mouse. J Neuroinflammation 2016; 13: 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barone R, Rizzo R, Tabbì G, et al. Nuclear peroxisome proliferator-activated Receptors (PPARs) as therapeutic targets of resveratrol for autism spectrum disorder. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20(8): 1878–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.