Abstract

N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline (AcSDKP) is an endogenous peptide that has been confirmed to show excellent organ‐protective effects. Even though originally discovered as a modulator of hemotopoietic stem cells, during the recent two decades, AcSDKP has been recognized as valuable antifibrotic peptide. The antifibrotic mechanism of AcSDKP is not yet clear; we have established that AcSDKP could target endothelial–mesenchymal transition program through the induction of the endothelial fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling pathway. Also, recent reports suggested the clinical significance of AcSDKP. The aim of this review was to update recent advances of the mechanistic action of AcSDKP and discuss translational research aspects.

Keywords: Angiotensin‐converting enzyme, Endothelial–mesenchymal transition, Fibroblast growth factor

N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline (AcSDKP) is an endogenous peptide that has been confirmed to show excellent organ‐protective effects. The antifibrotic mechanism of AcSDKP is not yet clear, we have established that AcSDKP could target endothelial mesenchymal transition program through the induction of the endothelial fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling pathway. Also, recent reports suggested the clinical significance of AcSDKP.

Introduction

With the recent type 2 diabetes pandemic, the number of people with diabetic complications could increase in the future. Diabetic kidney disease, such as diabetic nephropathy or other kidney insults, is the major cause of end‐stage renal disease and renal replacement therapy. Kidney fibrosis, which is characterized by matrix deposition and glomerulosclerosis, is the final pathway of progressive kidney diseases. Fundamentally, organ fibrosis is an important tissue repair process; progressive kidney fibrosis might be due to disruption of the normal wound healing mechanisms1, 2. The primary factors in the fibrosis pathway; for example, cellular induction of fibrosis or production of excess extracellular matrix (ECM), are difficult to identify. All cell types, either resident or non‐resident, in the kidney, such as resident fibroblasts, tubular epithelial cells, pericytes, endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, mesangial cells, podocytes and migrated bone marrow derived cells or inflammatory cells, are involved in this process3, 4. All these cell types could play vital roles in kidney fibrosis. Additionally, the conversion programs of cells from an epithelial or endothelial phenotype to a mesenchymal phenotype through epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and endothelial–mesenchymal transition (EndMT) could promote the generation of matrix‐producing mesenchymal‐like cells4, 5. However, there has been intensive discussion about the contribution or even the presence of EMT or EndMT. Most likely, the complete form of EMT or EndMT would make a minor contribution, if any; the presence of partial EMT or EndMT, the transition phase of epithelial/endothelial cells into mesenchymal cells, would likely have a major impact, because mesenchymal marker expression is common in either epithelial or endothelial cells in fibrotic kidney biopsies6, 7, 8. Therefore, targeting these mesenchymal programs is essential when considering therapeutic options for kidney fibrosis in diabetes. Diabetes is associated with endothelial damage induced by various insults, such as high glucose, hyperinsulinemia, oxidative stress and transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β. The present author and co‐authors have investigated endothelial damage and the EndMT program among the many potential mesenchymal programs in diabetic kidneys.

N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline (AcSDKP) is an endogenous peptide that has antifibrotic effects. The suppressive effects of AcSDKP on EndMT have been intensively analyzed. In this review, AcSDKP as a therapeutic option for diabetic kidney disease is focused on, especially the recent advances in endothelial protection induced by AcSDKP.

AcSDKP synthesis

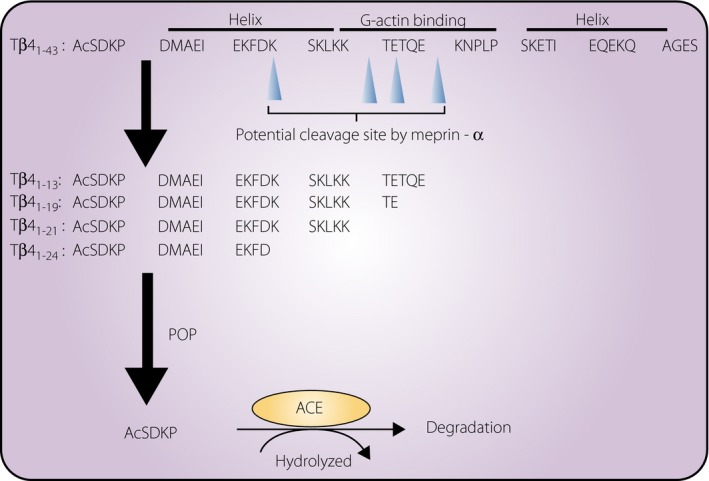

AcSDKP is a tetrapeptide isolated from fetal calf bone marrow9, and studies have shown its strong antifibrotic properties in various organs of multiple disease models. Although the molecular pathway of endogenous AcSDKP synthesis has not been fully elucidated, thymosin β4 (Tβ4), a globular‐actin‐sequestering peptide, is the strongest candidate for the AcSDKP precursor (Figure 1)10, 11. Small interfering ribonucleic acid (RNA) knockdown of Tβ4 in HeLa cells resulted in significant suppression of AcSDKP levels11. Elegantly, Lenfant et al. 10 showed that [3H] AcSDKP was produced when radiolabeled [3H] Tβ4 was incubated with either bone marrow cells or bone marrow lysate. AcSDKP is the N‐terminal sequence of Tβ4 (Figure 1), and a subsequent study showed that prolyl oligopeptidase (POP; in some studies described as prolyl endopeptidase) is responsible for Tβ4‐mediated AcSDKP production (Figure 1)12. Interestingly, POP has shown to be suppressed in patients with relapsing–emitting multiple sclerosis13.

Figure 1.

Generation of N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline (AcSDKP) from precursor polypeptide thymosin β4 (Tβ4). Tβ4 involves the amino acid sequence AcSDKP in the N‐terminal. Maprin‐α digested Tβ4 peptide into shorter sequence which can be cleaved by prolyl oligopeptidase (POP). In the second step, POP cleaves the AcSDKP sequence containing a shorter fragment of Tβ4 (1–13~24), and AcSDKP is excised out. Generated AcSDKP is degraded by angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE).

The Tβ4 peptide also shows antifibrotic and tissue‐protective effects. Tβ4 is a 43 amino acid peptide (4.9 kDa) that sequesters globular‐actin and regulates polymerization of F‐actin14, 15. Tβ4 is ubiquitously expressed in various organs14, 15. Tβ4 administration through either the intracardiac or the intraperitoneal route significantly rescued cardiac function and promoted neovascularization in a mouse model of experimental myocardial infarction16. Tβ4 also induced epicardial progenitor cell mobilization17. These organ‐protective effects of Tβ4 are primarily mediated by the synthesis of AcSDKP18, 19. In addition to Tβ4, Tβ15, which has the AcSDKP peptide sequence, might also contribute to the genesis of AcSDKP20, 21. The Tβ15 concentration is believed to be low compared with that of Tβ4 (~1,000‐fold lower); Tβ15 levels could be induced in some disease states, such as cancer20, 21. Interestingly, although the levels of AcSDKP were mostly suppressed, they were not completely abolished in mice with Tβ4 deficiency in the kidney and heart. These results might indicate that peptides homologous to Tβ4 (such as Tβ15) could compensate for the absence of Tβ422; however, caution is required in interpreting these data, because the AcSDKP level in the organs was determined with enzyme immunoassays for plasma/serum or urine, and such assays often show false positive values.

In the generation process of AcSDKP from Tβ4, recent evidence suggested the requirement of additional enzymatic cleavage processing. Kumar et al. 23 focused on the biology of POP. POP can cleave the peptide that is shorter than the sequence of 30 amino acids. However, Tβ4 is indeed 43 amino acids; therefore, theoretically, an additional enzymatic cleavage process should be required. Kumar et al.23 clearly showed that meprin‐α is a potential responsible enzyme to cleave Tβ4 and subsequently enable POP to cleave Tβ4 fragments to synthesize AcSDKP. Indeed, meprin‐α knockout mice showed significantly lower levels of AcSDKP. In regard to this, exogenous‐derived Tβ4‐increased AcSDKP levels in vivo were diminished by actinonin, the potential meprin‐α inhibitor23. These results suggested two‐step generation of AcSDKP from Tβ4 through meprin‐α and then POP (Figure 1).

AcSDKP degradation and the role of angiotensin‐converting enzyme

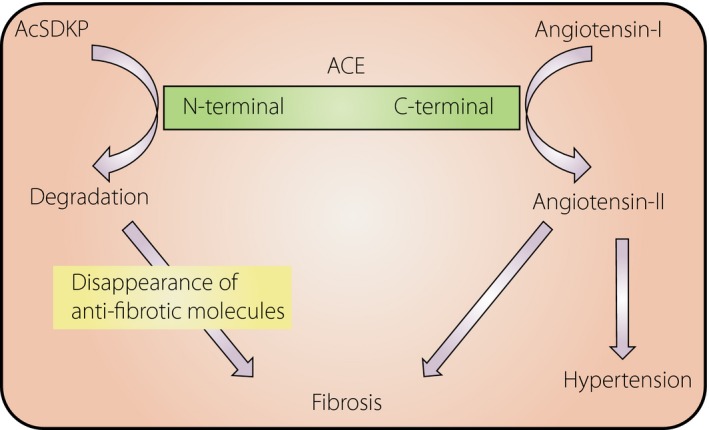

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) was confirmed to hydrolyze AcSDKP (Figures 1,2). AcSDKP is maintained at a low level in the plasma, and the AcSDKP concentration increased fivefold after captopril administration24. ACE has N‐terminus (ACEN) and C‐terminus (ACEC) zinc‐binding catalytic domains that are responsible for the cleavage of target substrates25, 26. The amino acid homology between the ACEN and ACEC domain is approximately 60%; approximately 89% homology can be observed in the catalytic regions26. The ACE gene in higher organisms is believed to be the result of the ancient gene duplication27, and the resultant ACE, which has two catalytic sites, is found in many organs and cells (somatic ACE). In contrast, an ACE composed of only the ACEC without the ACEN is only found in the testis, and this testis ACE is vital for fertility28, 29, 30. The testis ACE is likely the primitive type of ACE26. This duplication of the ACE gene occurred in early evolution, and separate promoter regions regulate the different enzyme expression levels (Figure 2)27, 31, 32. These similar, but distinct, catalytic domains were described in detail in a previous report33.

Figure 2.

The role of the distinct two catalytic sites of angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) in tissue fibrosis. The C‐terminal catalytic site of ACE shows a higher affinity to angiotensin I. In contrast, the N‐terminal catalytic site of ACE shows a high affinity to N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline (AcSDKP), and AcSDKP could be only degraded by the N‐terminal catalytic site.

Only the ACEN is contributing AcSDKP hydrolysis (Figure 2). In fact, the testis (where the germinal‐type ACE without the ACEN is expressed) is known to have higher levels of AcSDKP than other organs34, 35. A seminal report from Li et al.36 showed that ACEN‐knockout mice, which showed high levels of AcSDKP, had significantly less bleomycin‐induced lung fibrosis, as shown by lung histology and hydroxyproline levels, than ACEC knockout mice, suggesting the vital role of the ACEN in AcSDKP degradation. Furthermore, they investigated whether S‐17092, a POP inhibitor, could decrease the lung‐protective effects in ACEN knockout mice, and as expected, S‐17092 abolished lung protection in these mice. AcSDKP suppressed bleomycin‐induced lung fibrosis in wild‐type mice. Overall, that study showed that physiological elevation of AcSDKP through inhibition of the ACEN leads to endogenous antifibrosis programs in the lungs36.

Kidney fibrosis

After kidney insults, profibrotic cytokines accumulate in the microenvironment and subsequently stimulate target cell activation, producing ECM, which is fundamental for renal fibrogenesis. The majority of matrix‐producing cells responsible for the production of interstitial matrix components (including fibronectin and type I and type III collagens) are fibroblasts37. Activated fibroblasts or myofibroblasts, which are characterized by increased expression of alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA), are believed to be a significant source of ECM‐producing renal cells. However, almost all cell types in the kidney (either resident or non‐resident kidney cells) play a vital role in ECM production38. As described earlier, these cell types develop a profibrotic phenotype, and TGF‐β, a profibrotic cytokine that plays a central role in fibrogenesis, has an essential role in this process. Thus, inhibition of either TGF‐β or the TGF‐β‐stimulated Smad transcription factor signaling pathway shows antifibrotic effects39. Activated fibroblasts in the kidney express αSMA and are often called myofibroblasts, which show unique contractile properties37. However, αSMA expression was observed not only in fibroblasts, but also in tubular cells6 and endothelial cells8, suggesting that these cells could contribute to kidney fibrosis through EMT or EndMT program. Although the presence of these programs is controversial, at least in diabetic models, these processes are most likely important in kidney fibrosis. Interestingly, most studies did not detect EMT or EndMT in unilateral ureteral obstruction or ischemic reperfusion injury models. Unilateral ureteral obstruction is often utilized in kidney fibrosis studies, but the relationship of this model to human kidney disease is unclear. Differences are observed in the progression time and the background physiological condition. In diabetic models, EMT or EndMT has been detected (>150 papers on EMT and 20 papers on EndMT). Therefore, these programs should still be credible to be investigated in kidney fibrosis in diabetes.

Antifibrotic effects of AcSDKP

AcSDKP has been confirmed to show antifibrotic organ‐protective effects in diverse preclinical models18, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45. In the first study of db/db mice42, the present author and co‐authors showed the preclinical utility of AcSDKP in protection against diabetic kidney disease, with a focus on kidney fibrosis.

Although various studies have shown the apparent antifibrotic effects in vivo and the direct effects of AcSDKP on culture fibroblasts in vitro, the effects of AcSDKP on fibroblast activation/myofibroblast differentiation programs are still unclear. Peng et al.46 reported that AcSDKP inhibited TGF‐β1‐induced differentiation of human cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, as shown by increased expression of αSMA and the embryonic isoform of smooth muscle myosin. Xu et al.47 reported that AcSDKP inhibits myofibroblast accumulation in silicotic nodules in the lung and the TGF‐β1‐induced myofibroblast differentiation of pulmonary fibroblasts. In a study of the AcSDKP‐inhibited myofibroblast differentiation program, the present author and co‐authors focused on the anti‐EndMT effects of AcSDKP associated with TGF‐β‐Smad signal transduction33, 48, 49, 50, 51.

More than 15 years ago, the present author and co‐authors found that AcSDKP inhibited TGF‐β‐induced Smad2 phosphorylation, and the anti‐TGF‐β/Smad pathway is the key to understanding the antifibrotic effects of AcSDKP in rat cardiac fibroblasts and human mesangial cells52, 53. Indeed, AcSDKP is the first endogenous circulatory polypeptide shown to inhibit TGF‐β‐induced Smad2 phosphorylation (only a Smad2 phosphorylation antibody was available at this time). Smads are TGF‐β superfamily‐specific transcription factors and are essential players in signal transduction39, 54, 55, 56. Smad transcription factors are categorized as follows: (i) receptor‐regulated (R)‐Smads (Smad2 and 3); (ii) common (co)‐Smads (Smad4); and (iii) inhibitory (I)‐Smads (Smad6 and 7). After TGF‐β binding to the type II receptor, this receptor physically interacts with and subsequently induces serine residue phosphorylation on the type I receptor (TGF‐βRI)57. The phosphorylated type I receptor interacts with and phosphorylates R‐Smads, and phosphorylated R‐Smads subsequently interact with co‐Smads and translocate into the nucleus with the help of importin‐β58. The R‐co‐Smad heterodimer binds to the Smad‐binding elements of the target promoter deoxyribonucleic acid regions, whereas I‐Smads localize to the nucleus53 and translocate to the cytoplasm from the nucleus after stimulation with TGF‐β to inhibit R‐Smad phosphorylation by type I receptors.

The precise molecular mechanisms by which AcSDKP suppresses TGF‐β‐induced R‐Smad phosphorylation are still unclear; I‐Smads could have a role in this process. The present author and co‐authors first reported that the I‐Smad Smad7 was translocated after AcSDKP incubation in human mesangial cells,53 and several groups have shown that the Smad7 levels were indeed elevated by AcSDKP administration in vivo 43. However, alternative molecular mechanisms by which AcSDKP‐inhibited R‐Smad phosphorylation could be linked to fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor (FGFR)49 and FGFR‐associated induction of the microRNA (miRNA) let‐7‐mediated suppression of TGF‐β159.

FGFR1

Fibroblast growth factor signaling, mediated by FGFRs, has an important role in maintaining endothelial homeostasis and cardiovascular integrity60, 61, 62, 63. The FGFR family, a subfamily of receptor tyrosine kinases, consists of four members (FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3 and FGFR4)64. Chen et al.59 reported that FGF/FGFR1 signaling suppressed TGF‐β‐induced EndMT through inducing the miRNA let‐7. The present author and co‐authors showed that a fibrotic strain of diabetic mice displayed suppression of FGFR1 on endothelial cells, and that AcSDKP restored the levels of endothelial FGFR1 in these mice49. FGFR1 is a fundamental molecule that inhibits the TGF‐β/Smad signaling pathway in endothelial cells65. Additionally, a key adaptor of the FGFR signaling pathway, FGF receptor substrate 2, has been shown to suppress EndMT induction, and endothelial‐specific FGF receptor substrate 2 knockout mice showed increased levels of EndMT‐ and EndMT‐derived smooth muscle cells59. A deficiency in mesodermal FGF receptor substrate 2 resulted in misalignment and hypoplasia of the cardiac outflow tract66. FGFR1 also plays an essential role in cardiomyocyte development and cardiac chamber identity in the developing ventricle67, 68.

Effect of AcSDKP on the FGFR1‐mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 4 pathway

Mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 4 (MAP4K4), a member of the Sterile 20 family of kinases, has various biological roles69. In endothelial cells, MAP4K4 has been shown to suppress integrin β1 activity by inducing moesin70. Integrin β1 stimulates EMT and organ fibrosis through TGF‐β/Smad signaling activation71, 72, 73. The present author and co‐authors showed that the interaction between dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP)‐4 and integrin β1 induces EndMT, and that this interaction disrupts endothelial homeostasis74. Misshapen (msn) kinases (the mammalian orthologs of MAP4K4) have been shown to suppress TGF‐β/Smad signaling75.

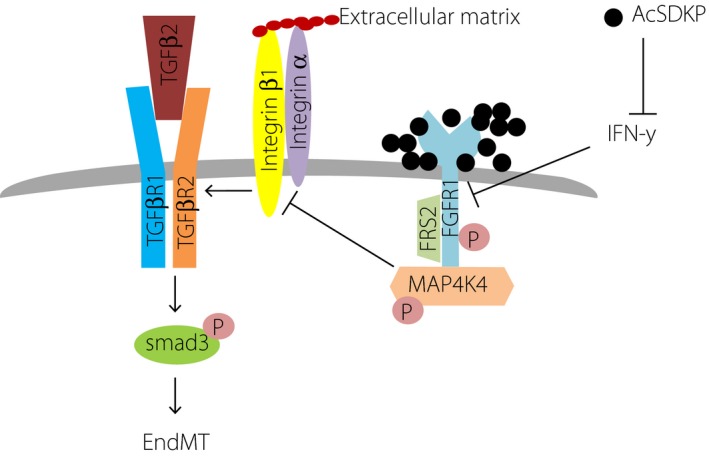

We found that AcSDKP restored the TGF‐β2‐suppressed levels of FGFR1 on endothelial cells, and that the FGFR1 levels were associated with MAP4K4 phosphorylation (Figure 3). AcSDKP was detected in close proximity to FGFR1. TGF‐β2 suppressed FGFR1, and AcSDKP restored the FGFR1 levels in association with the AcSDKP–FGFR1 interaction (Figure 3); however, mutant peptides, such as AcDSPK, AcSDKA and AcADKP, did not alter the levels of FGFR150. FGFR1 physically interacted with phosphorylated MAP4K4, and neutralizing FGFR1 abolished the AcSDKP‐induced MAP4K4 phosphorylation (Figure 3). Additionally, knockdown of MAP4K4 in endothelial cells abolished the anti‐EndMT and anti‐TGF‐β1/Smad effects of AcSDKP. Furthermore, the hearts of diabetic mice showed suppressed levels of both FGFR1 and MAP4K4 associated with Smad3 phosphorylation on endothelial cells; AcSDKP intervention normalized all of these parameters50. All these data showed that the FGFR1–MAP4K4 pathway is involved in the anti‐EndMT effects of AcSDKP (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline (AcSDKP)–fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1)–mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 4 (MAP4K4) axis‐induced suppression of integrin–transforming growth factor‐β receptors (TGFβRs) interaction and endothelial mesenchymal transition (EndMT). AcSDKP shows close proximity and would stabilize FGFR1. Alternatively, AcSDKP suppresses interferon‐γ (IFN‐γ), which inhibits FGFR1 levels in endothelial cells. FGFR1 physically interacts with MAP4K4 by which integrin β1 signaling is suppressed. Integrin β1 is essential for the heterodimer formations of TGFβRs; integrin β1 suppression directly results in the suppression of TGF‐β1‐smad signaling and EndMT.

β‐Klotho

Klotho proteins are type I single‐pass transmembrane proteins that share homology with family 1 β‐glycosidases, and are composed of α‐klotho (KLA)76, β‐klotho (KLB)77 and γ‐klotho78. Klotho proteins consist of short intracellular and relatively large extracellular domains with two internal repeats, termed KL1 and KL279. Klotho proteins act as coreceptors of FGFRs, facilitating the binding of the FGF19 subfamily on FGFRs (e.g., KLA for FGF23 and KLB for FGF19/FGF21)80, 81, and have emerged as essential metabolism‐regulating factors through their interactions during the past decades82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88.

KLA was shown to have anti‐aging effects76, and the functions of KLA in endothelial cells and the cardiovascular system have been reported89, 90, 91, 92. However, the biological significance of KLB is still unclear. KLB is expressed in human umbilical vein endothelial cells93 and human brain microvascular endothelial cells94, where KLB contributes to the formation of the blood–brain barrier.

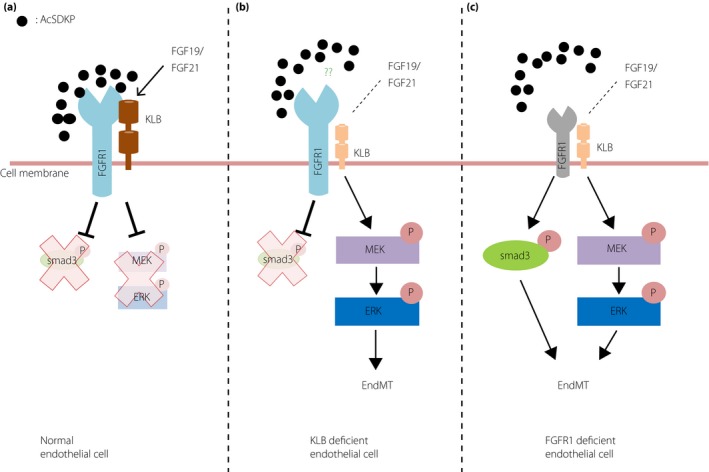

We have reported that FGFR1 deficiency induced activation of TGF‐β/Smad3 signaling50; however, KLB knockdown was not associated with an obvious alteration of Smad3 phosphorylation51. As KLB knockdown did not directly alter the FGFR1 levels, FGFR1 could be essential for the regulation of Smad3 phosphorylation. In contrast, the mitogen‐activated protein kinase signaling pathways involving mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)1/2 and extracellular signal‐regulated kinases 1/2 were activated51. Consistent with this finding, a MEK inhibitor decreased KLB deficiency‐induced EndMT. Liu et al.95 reported that KLB overexpression inhibited EMT, the epithelial program sharing similar molecular mechanisms to EndMT, through the suppression of mitogen‐activated protein kinase. Unexpectedly, the KLB‐deficient activated mitogen‐activated protein kinase pathway without Smad3 phosphorylation is sufficient for the induction of EndMT. Either FGF19 or FGF21, a ligand of the FGFR1–KLB complex, synergistically diminished EndMT and MEK–extracellular signal‐regulated kinase pathway activation in AcSDKP‐treated cultured endothelial cells (Figure 4)51. Inhibition of FGFR1 and KLB protein levels was found in streptozotocin‐induced diabetic mouse hearts; AcSDKP restored these levels, suggesting the important in vivo effects of AcSDKP on FGFR1 and KLB complex formation51.These reports showed the essential role of the FGFR1‐KLB complex in the suppression of EndMT by AcSDKP, but the qualitative difference between Smad‐dependent EndMT and Smad‐independent, mitogen‐activated protein kinase‐dependent EndMT should be further investigated.

Figure 4.

Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1)–β klotho complex plays roles in endothelial homeostasis. (a) In normal endothelial cells, N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline (AcSDKP)‐induced FGFR1 levels and FGFR1–KLB complex. Such FGFR1–KLB complex is essential for the endothelial homeostasis by inhibiting both smad3 and mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)–extracellular signal‐regulated kinases (ERK) signaling pathway. (b) In the endothelial cells with KLB deficiency, MEK–ERK pathway dependent EndMT could be induced. KLB deficiency is not associated with alteration in FGFR1 levels in endothelial cells. AcSDKP cannot inhibit MEK–ERK pathway‐dependent EndMT in KLB‐deficient endothelial cells. (c) In the endothelial cells with FGFR1 deficiency, KLB levels are also significantly diminished, and both smad3 and the MEK–ERK pathway are activated. FGFR1‐deficient endothelial cells also show AcSDKP‐resistant endothelial mesenchymal transition (EndMT).

MiRNA cross‐talk

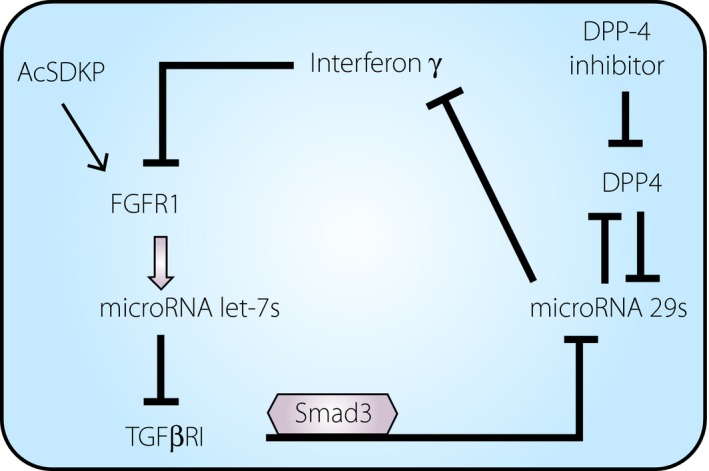

As described earlier, AcSDKP‐induced FGFR1 is associated with the anti‐EndMT miRNA let‐7 that targets TGF‐βRI; miRNA let‐7 induction through the AcSDKP–FGFR1 axis played further roles in endothelial protection through inducing miRNA‐298, 96, 97 and vice versa (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Micro ribonucleic acid (miRNA) cross‐talk between miR 29 and miR let‐7 in the anti‐endothelial mesenchymal transition action of N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline (AcSDKP). AcSDKP increases the levels of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) and, subsequently, miR let‐7s are induced. MiR let‐7 suppressed transforming growth factor β receptor (TGFβR1) and downstream Smad3 signaling, the major miR 29 inhibitory pathway. Therefore, the cells treated with AcSDKP also show induction of miR 29. miR 29 suppressed profibrotic and inflammatory cytokines and proteins, such as interferon‐γ, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4(DPP‐4) and so on. Interferon‐γ is known to suppress FGFR1. Interestingly, DPP‐4 inhibitor‐mediated suppression of DPP‐4 subsequently induced miR 29, and such DPP‐4 inhibitor‐activated miR 29 induced FGFR1‐dependent miR let‐7, as vice versa.

[Correction added on 1 April 2020, after first online publication: The figure has been amended to match the original.]

In a follow‐up study, the present authors and co‐authors found that AcSDKP‐induced let‐7 was associated with miRNA 29, and miRNA 29 expression was abolished by an antagomir for miRNA let‐7, suggesting antifibrotic cross‐talk between miRNA let‐7 and miRNA 2948. This conclusion is reasonable, because activation of TGF‐β signaling significantly suppresses miRNA 29, and the induction of miRNA let‐7 by miRNA 29 in endothelial cells is a reasonable sequence (Figure 5). Interestingly, miRNA 29 induction also suppressed EndMT, and was associated with the induction of miRNA let‐748. In this complex process, the present author and co‐authors identified the precise molecular mechanisms underlying the miRNA cross‐talk. MiRNA 29 targets several profibrotic molecules, such as integrin β1 and DPP‐448. Integrin β1 and DPP‐4 form a complex on the cell surface of endothelial cells, and induce TGF‐β receptor heterodimer formation and subsequent activation of the Smad signaling pathway74. TGF‐β‐induced EndMT was also inhibited by the DPP‐4 inhibitor linagliptin, which further restored miRNA 29. The induction of miRNA 29 is likely important for the antifibrotic effects of AcSDKP. MiRNA 29 also targets interferon‐γ, a cytokine related to inflammation and organ fibrosis. Interferon‐γ can inhibit endothelial FGFR1, the key mediator of miRNA let‐7 induction and the suppression of EndMT by AcSDKP59. The present author and co‐authors showed that the AcSDKP–FGFR1 axis was critical for maintaining endothelial mitochondrial biogenesis through induction of miRNA let‐7b‐5p98. These data showed that the AcSDKP–FGFR1 axis on endothelial cells is essential for endothelial homeostasis through the cross‐talk between miRNA let‐7 and miRNA 29 (Figure 5).

Perspective: Translational research of AcSDKP

As described earlier, AcSDKP has the potential to combat fibroproliferative diseases, such as kidney complications in diabetes. Although AcSDKP has not yet been translated into the clinic, recent data have shown that AcSDKP could be a useful clinical biomarker in some disease conditions.

Sodium intake is a known detrimental factor in the clinical outcome of renal diseases99. Kwakernaak et al.100 examined the potential relevance of AcSDKP in renal protection. The researchers enrolled 46 non‐diabetic chronic kidney disease patients with overt proteinuria who showed mild‐to‐moderate renal insufficiency. In a cross‐over design/double‐blind analysis for a 6‐week study period with a regular or a low‐sodium diet and either lisinopril or lisinopril plus valsartan, sodium restriction was confirmed to increase the plasma level of AcSDKP during either single or dual renin–angiotensin system blockade100. Interestingly, a recent report utilizing mice with knockout of the N‐terminal sequence of ACE, which resulted in AcSDKP degradation, found that they showed increased levels of AcSDKP associated with enhanced urine excretion of sodium without alterations in renal angiotensin II levels101. The molecular regulation and physiological relevance of the interaction of AcSDKP levels and sodium intake/excretion have not yet been elucidated, and further research is required.

Finally, the present author recently reported that the urine levels of AcSDKP could be a potential biomarker of alteration of renal function in normoalbuminuric diabetes patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 102. When compared with that observed two decades ago, the diabetes population with renal deficiency without urine albuminuria has increased103, 104. The explanation for these changes is unknown, but evidence‐based treatment of diabetes patients (such as appropriate blood glucose control and renin–angiotensin system blockade) could result in the reduction of urine albumin with a decrease in eGFR103, 104. Urine albumin‐negative diabetes patients rarely show a progressive decline in renal function, few, but some, can progress to end‐stage renal disease104. Most importantly, there is no established biomarker for this urine albumin‐negative diabetes population. The present author and co‐authors have already shown that CD‐1 mice, a fibrotic strain with diabetes, displayed a diabetes‐associated decline in urine AcSDKP levels48.

Based on this background, the present author and co‐authors hypothesized that the urine AcSDKP‐to‐urine creatine ratio can predict kidney injury and future renal function. A total of 21 diabetes patients with normoalbuminuria and an eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 were divided into two groups based on the median values: low or high urinary AcSDKP groups (uAcSDKP/Crlow or uAcSDKP/Crhigh) in the first morning urine and follow up at ~4 years to monitor eGFR. In the uAcSDKP/Crhigh group, the alteration in eGFR (ΔeGFRop [ΔeGFR observational periods]) showed significant stability compared with that of the uAcSDKP/Crlow group over time (P = 0.003, χ2 = 8.58). Levels of the urine kidney injury molecule‐1 (uKim‐1), which is known to increase in the injured kidney, were also measured, and in the low uKim‐1 group, ΔeGFRop showed stable kidney function over time compared with that of the high uKim‐1 group (P = 0.004, χ2 = 8.38). There was no significant interaction between the levels of AcSDKP and Kim‐1. Patients who had both uAcSDKP/Crhigh and uKim‐1low were much more likely to show stable ΔeGFRop (P < 0.001, χ2 = 30.4) than other patients. The plasma AcSDKP level (P = 0.015, χ2 = 5.94) can also weakly, but significantly, predict ΔeGFRop. As kidney tubulointerstitial fibrosis is a major determinant of kidney dysfunction, the antifibrotic peptide, AcSDKP, could be a functional biomarker for kidney injury and a future decline in renal function102.

Conclusion

A therapeutic strategy with appropriate molecular biomarkers is essential to prevent kidney disease progression in diabetes. Fibrosis is a pathological process that destroys normal parenchyma; therefore, an antifibrotic strategy based on the mechanisms underlying kidney fibrogenesis could help to inhibit diabetic kidney disease progression. From this point of view, further elucidation of the potential of AcSDKP should be carried out. AcSDKP could be valuable, as both a therapeutic treatment and molecular biomarker in kidney disease, especially for diabetes patients.

Disclosure

KK is an advisory board member of Boehringer Ingelheim and collaborates with a study on a similar topic contained in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science awarded to KK (19K08738). KK received lecture fees from Daiichi‐Sankyo Pharma,Tanabe‐Mitsubishi Pharma, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, Taisho Pharma. Boehringer Ingelheim (Japan) and MitsubishiTanabe Pharma, and Ono Pharmaceutical contributed to establishing the Division of Anticipatory Molecular Food Science and Technology. KK is under a consultancy agreement with Boehringer Ingelheim.

J Diabetes Investig 2020; 11: 516–526

References

- 1. Pinzani M. Welcome to fibrogenesis & tissue repair. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2008; 1: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wynn TA. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol 2008; 214: 199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zeisberg M, Neilson EG. Mechanisms of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21: 1819–1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boor P, Ostendorf T, Floege J. Renal fibrosis: novel insights into mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Nephrol 2010; 6: 643–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zeisberg M, Duffield JS. Resolved: EMT produces fibroblasts in the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21: 1247–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Loeffler I, Wolf G. Epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition in diabetic nephropathy: fact or fiction? Cells 2015; 4: 631–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kanasaki K, Kanda Y, Palmsten K, et al Integrin beta1‐mediated matrix assembly and signaling are critical for the normal development and function of the kidney glomerulus. Dev Biol 2008; 313: 584–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kanasaki K, Shi S, Kanasaki M, et al Linagliptin‐mediated DPP‐4 inhibition ameliorates kidney fibrosis in streptozotocin‐induced diabetic mice by inhibiting endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition in a therapeutic regimen. Diabetes 2014; 63: 2120–2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lenfant M, Wdzieczak‐Bakala J, Guittet E, et al Inhibitor of hematopoietic pluripotent stem cell proliferation: purification and determination of its structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1989; 86: 779–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grillon C, Rieger K, Bakala J, et al Involvement of thymosin beta 4 and endoproteinase Asp‐N in the biosynthesis of the tetrapeptide AcSerAspLysPro a regulator of the hematopoietic system. FEBS Lett 1990; 274: 30–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu JM, Garcia‐Alvarez MC, Bignon J, et al Overexpression of the natural tetrapeptide acetyl‐N‐ser‐asp‐lys‐pro derived from thymosin beta4 in neoplastic diseases. Ann NY Acad Sci 2010; 1194: 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cavasin MA, Rhaleb NE, Yang XP, et al Prolyl oligopeptidase is involved in release of the antifibrotic peptide Ac‐SDKP. Hypertension 2004; 43: 1140–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tenorio‐Laranga J, Coret‐Ferrer F, Casanova‐Estruch B, et al Prolyl oligopeptidase is inhibited in relapsing‐remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation 2010; 7: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huff T, Muller CS, Otto AM, et al beta‐Thymosins, small acidic peptides with multiple functions. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2001; 33: 205–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hannappel E. Thymosin beta4 and its posttranslational modifications. Ann NY Acad Sci 2010; 1194: 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bock‐Marquette I, Saxena A, White MD, et al Thymosin beta4 activates integrin‐linked kinase and promotes cardiac cell migration, survival and cardiac repair. Nature 2004; 432: 466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smart N, Risebro CA, Melville AA, et al Thymosin beta4 induces adult epicardial progenitor mobilization and neovascularization. Nature 2007; 445: 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zuo Y, Chun B, Potthoff SA, et al Thymosin beta4 and its degradation product, Ac‐SDKP, are novel reparative factors in renal fibrosis. Kidney Int 2013; 84: 1166–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sosne G, Qiu P, Goldstein AL, et al Biological activities of thymosin beta4 defined by active sites in short peptide sequences. FASEB J 2010; 24: 2144–2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Banyard J, Hutchinson LM, Zetter BR. Thymosin beta‐NB is the human isoform of rat thymosin beta15. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007; 1112: 286–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dhaese S, Vandepoele K, Waterschoot D, et al The mouse thymosin beta15 gene family displays unique complexity and encodes a functional thymosin repeat. J Mol Biol 2009; 387: 809–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kumar N, Liao TD, Romero CA, et al Thymosin beta4 deficiency exacerbates renal and cardiac injury in angiotensin‐II‐induced hypertension. Hypertension 2018; 71: 1133–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kumar N, Nakagawa P, Janic B, et al The anti‐inflammatory peptide Ac‐SDKP is released from thymosin‐beta4 by renal meprin‐alpha and prolyl oligopeptidase. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2016; 310: F1026–F1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Azizi M, Rousseau A, Ezan E, et al Acute angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibition increases the plasma level of the natural stem cell regulator N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline. J Clin Investig 1996; 97: 839–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wei L, Alhenc‐Gelas F, Corvol P, et al The two homologous domains of human angiotensin I‐converting enzyme are both catalytically active. J Biol Chem 1991; 266: 9002–9008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bernstein KE, Shen XZ, Gonzalez‐Villalobos RA, et al Different in vivo functions of the two catalytic domains of angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE). Curr Opin Pharmacol 2011; 11: 105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hubert C, Houot AM, Corvol P, et al Structure of the angiotensin I‐converting enzyme gene. Two alternate promoters correspond to evolutionary steps of a duplicated gene. J Biol Chem 1991; 266: 15377–15383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krege JH, John SW, Langenbach LL, et al Male‐female differences in fertility and blood pressure in ACE‐deficient mice. Nature 1995; 375: 146–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Esther CR, Marino EM, Howard TE, et al The critical role of tissue angiotensin‐converting enzyme as revealed by gene targeting in mice. J Clin Investig 1997; 99: 2375–2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fuchs S, Frenzel K, Hubert C, et al Male fertility is dependent on dipeptidase activity of testis ACE. Nat Med 2005; 11: 1140–1142; author reply 2–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Howard TE, Shai SY, Langford KG, et al Transcription of testicular angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) is initiated within the 12th intron of the somatic ACE gene. Mol Cell Biol 1990; 10: 4294–4302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Langford KG, Shai SY, Howard TE, et al Transgenic mice demonstrate a testis‐specific promoter for angiotensin‐converting enzyme. J Biol Chem 1991; 266: 15559–15562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kanasaki K, Nagai T, Nitta K, et al N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline: a valuable endogenous anti‐fibrotic peptide for combating kidney fibrosis in diabetes. Front Pharmacol 2014; 5: 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stephan J, Melaine N, Ezan E, et al Source, catabolism and role of the tetrapeptide N‐acetyl‐ser‐asp‐lys‐Pro within the testis. J Cell Sci 2000; 113(Pt 1): 113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fuchs S, Xiao HD, Cole JM, et al Role of the N‐terminal catalytic domain of angiotensin‐converting enzyme investigated by targeted inactivation in mice. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 15946–15953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li P, Xiao HD, Xu J, et al Angiotensin‐converting enzyme N‐terminal inactivation alleviates bleomycin‐induced lung injury. Am J Pathol 2010; 177: 1113–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Strutz F, Zeisberg M. Renal fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17: 2992–2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kanasaki K, Taduri G, Koya D. Diabetic nephropathy: the role of inflammation in fibroblast activation and kidney fibrosis. Front Endocrinol 2013; 4: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miyazono K. TGF‐beta signaling by Smad proteins. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2000; 11: 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rhaleb NE, Peng H, Harding P, et al Effect of N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline on DNA and collagen synthesis in rat cardiac fibroblasts. Hypertension 2001; 37: 827–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fromes Y, Liu JM, Kovacevic M, et al The tetrapeptide acetyl‐serine‐aspartyl‐lysine‐proline improves skin flap survival and accelerates wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2006; 14: 306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shibuya K, Kanasaki K, Isono M, et al N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline prevents renal insufficiency and mesangial matrix expansion in diabetic db/db mice. Diabetes 2005; 54: 838–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Omata M, Taniguchi H, Koya D, et al N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline ameliorates the progression of renal dysfunction and fibrosis in WKY rats with established anti‐glomerular basement membrane nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17: 674–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Castoldi G, di Gioia CR, Bombardi C, et al Renal antifibrotic effect of N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline in diabetic rats. Am J Nephrol 2013; 37: 65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Castoldi G, di Gioia CR, Bombardi C, et al Prevention of myocardial fibrosis by N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline in diabetic rats. Clin Sci 2010; 118: 211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Peng H, Carretero OA, Peterson EL, et al Ac‐SDKP inhibits transforming growth factor‐beta1‐induced differentiation of human cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2010; 298: H1357–H1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xu H, Yang F, Sun Y, et al A new antifibrotic target of Ac‐SDKP: inhibition of myofibroblast differentiation in rat lung with silicosis. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e40301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Srivastava SP, Shi S, Kanasaki M, et al Effect of antifibrotic MicroRNAs crosstalk on the action of N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline in diabetes‐related kidney fibrosis. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 29884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nagai T, Kanasaki M, Srivastava S, et al N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline inhibits diabetes‐associated kidney fibrosis and endothelial‐mesenchymal transition. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014: 696475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li J, Shi S, Srivastava SP, et al FGFR1 is critical for the anti‐endothelial mesenchymal transition effect of N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline via induction of the MAP4K4 pathway. Cell Death Dis 2017; 8: e2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gao R, Kanasaki K, Li J, et al betaklotho is essential for the anti‐endothelial mesenchymal transition effects of N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline. FEBS Open Bio 2019; 9: 1029–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pokharel S, Rasoul S, Roks AJ, et al N‐acetyl‐Ser‐Asp‐Lys‐Pro inhibits phosphorylation of Smad2 in cardiac fibroblasts. Hypertension 2002; 40: 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kanasaki K, Koya D, Sugimoto T, et al N‐Acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline inhibits TGF‐beta‐mediated plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 expression via inhibition of Smad pathway in human mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14: 863–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Border WA, Noble NA. Transforming growth factor‐beta in glomerular injury. Exp Nephrol 1994; 2: 13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Border WA, Noble NA. Transforming growth factor beta in tissue fibrosis. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 1286–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Border WA, Brees D, Noble NA. Transforming growth factor‐beta and extracellular matrix deposition in the kidney. Contrib Nephrol 1994; 107: 140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wrana JL, Carcamo J, Attisano L, et al The type II TGF‐beta receptor signals diverse responses in cooperation with the type I receptor. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol 1992; 57: 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Xiao Z, Liu X, Henis YI, et al A distinct nuclear localization signal in the N terminus of Smad 3 determines its ligand‐induced nuclear translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 7853–7858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chen PY, Qin L, Barnes C, et al FGF regulates TGF‐beta signaling and endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition via control of let‐7 miRNA expression. Cell Rep 2012; 2: 1684–1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Murakami M, Nguyen LT, Hatanaka K, et al FGF‐dependent regulation of VEGF receptor 2 expression in mice. J Clin Investig 2011; 121: 2668–2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hatanaka K, Simons M, Murakami M. Phosphorylation of VE‐cadherin controls endothelial phenotypes via p120‐catenin coupling and Rac1 activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011; 300: H162–H172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yang X, Liaw L, Prudovsky I, et al Fibroblast growth factor signaling in the vasculature. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2015; 17: 509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Murakami M, Nguyen LT, Zhuang ZW, et al The FGF system has a key role in regulating vascular integrity. J Clin Investig 2008; 118: 3355–3366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tiong KH, Mah LY, Leong CO. Functional roles of fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs) signaling in human cancers. Apoptosis 2013; 18: 1447–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Chen PY, Qin L, Tellides G, et al Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is a key inhibitor of TGFbeta signaling in the endothelium. Sci Signal 2014; 7: ra90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zhang J, Lin Y, Zhang Y, et al Frs2alpha‐deficiency in cardiac progenitors disrupts a subset of FGF signals required for outflow tract morphogenesis. Development 2008; 135: 3611–3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dell'Era P, Ronca R, Coco L, et al Fibroblast growth factor receptor‐1 is essential for in vitro cardiomyocyte development. Circ Res 2003; 93: 414–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pradhan A, Zeng XI, Sidhwani P, et al FGF signaling enforces cardiac chamber identity in the developing ventricle. Development 2017; 144: 1328–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Virbasius JV, Czech MP. Map4k4 signaling nodes in metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2016; 27: 484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Vitorino P, Yeung S, Crow A, et al MAP4K4 regulates integrin‐FERM binding to control endothelial cell motility. Nature 2015; 519: 425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Liu S, Kapoor M, Denton CP, et al Loss of beta1 integrin in mouse fibroblasts results in resistance to skin scleroderma in a mouse model. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60: 2817–2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yeh YC, Wei WC, Wang YK, et al Transforming growth factor‐{beta}1 induces Smad3‐dependent {beta}1 integrin gene expression in epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition during chronic tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2010; 177: 1743–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Chen X, Wang H, Liao HJ, et al Integrin‐mediated type II TGF‐beta receptor tyrosine dephosphorylation controls SMAD‐dependent profibrotic signaling. J Clin Investig 2014; 124: 3295–3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Shi S, Srivastava SP, Kanasaki M, et al Interactions of DPP‐4 and integrin beta1 influences endothelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition. Kidney Int 2015; 88: 479–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kaneko S, Chen X, Lu P, et al Smad inhibition by the Ste20 kinase Misshapen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108: 11127–11132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kuro‐o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, et al Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature 1997; 390: 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ito S, Kinoshita S, Shiraishi N, et al Molecular cloning and expression analyses of mouse betaklotho, which encodes a novel Klotho family protein. Mech Dev 2000; 98: 115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ito S, Fujimori T, Hayashizaki Y, et al Identification of a novel mouse membrane‐bound family 1 glycosidase‐like protein, which carries an atypical active site structure. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002; 1576: 341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Dalton GD, Xie J, An SW, et al New Insights into the Mechanism of Action of Soluble Klotho. Front Endocrinol 2017; 8: 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lan T, Morgan DA, Rahmouni K, et al FGF19, FGF21, and an FGFR1/beta‐klotho‐activating antibody act on the nervous system to regulate body weight and glycemia. Cell Metab 2017; 26: 709–718. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kurosu H, Choi M, Ogawa Y, et al Tissue‐specific expression of betaKlotho and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor isoforms determines metabolic activity of FGF19 and FGF21. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 26687–26695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tomlinson E, Fu L, John L, et al Transgenic mice expressing human fibroblast growth factor‐19 display increased metabolic rate and decreased adiposity. Endocrinology 2002; 143: 1741–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kharitonenkov A, Shiyanova TL, Koester A, et al FGF‐21 as a novel metabolic regulator. J Clin Investig 2005; 115: 1627–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lin BC, Wang M, Blackmore C, et al Liver‐specific activities of FGF19 require Klotho beta. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 27277–27284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Suzuki M, Uehara Y, Motomura‐Matsuzaka K, et al betaKlotho is required for fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 21 signaling through FGF receptor (FGFR) 1c and FGFR3c. Mol Endocrinol 2008; 22: 1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kharitonenkov A, Dunbar JD, Bina HA, et al FGF‐21/FGF‐21 receptor interaction and activation is determined by betaKlotho. J Cell Physiol 2008; 215: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Adams AC, Coskun T, Rovira AR, et al Fundamentals of FGF19 & FGF21 action in vitro and in vivo . PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e38438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Adams AC, Cheng CC, Coskun T, et al FGF21 requires betaklotho to act in vivo . PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e49977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ikushima M, Rakugi H, Ishikawa K, et al Anti‐apoptotic and anti‐senescence effects of Klotho on vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006; 339: 827–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Markiewicz M, Panneerselvam K, Marks N. Role of Klotho in migration and proliferation of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Microvasc Res 2016; 107: 76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Richter B, Haller J, Haffner D, et al Klotho modulates FGF23‐mediated NO synthesis and oxidative stress in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Pflugers Arch 2016; 468: 1621–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ghosh AK, Quaggin SE, Vaughan DE. Molecular basis of organ fibrosis: potential therapeutic approaches. Exp Biol Med 2013; 238: 461–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Wang XM, Song SS, Xiao H, et al Fibroblast growth factor 21 protects against high glucose induced cellular damage and dysfunction of endothelial nitric‐oxide synthase in endothelial cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 2014; 34: 658–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Chen J, Hu J, Liu H, et al FGF21 protects the blood‐brain barrier by upregulating PPARgamma via FGFR1/beta‐klotho after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2018; 35: 2091–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Liu Z, Qi S, Zhao X, et al Metformin inhibits 17beta‐estradiol‐induced epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition via betaKlotho‐related ERK1/2 signaling and AMPKalpha signaling in endometrial adenocarcinoma cells. Oncotarget 2016; 7: 21315–21331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Srivastava SP, Koya D, Kanasaki K. MicroRNAs in kidney fibrosis and diabetic nephropathy: roles on EMT and EndMT. Biomed Res Int 2013; 2013: 125469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Nitta K, Shi S, Nagai T, et al Oral administration of N‐Acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline ameliorates kidney disease in both type 1 and type 2 diabetic mice via a therapeutic regimen. Biomed Res Int 2016; 2016: 9172157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hu Q, Li J, Nitta K, et al FGFR1 is essential for N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline regulation of mitochondrial dynamics by upregulating microRNA let‐7b‐5p. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018; 495: 2214–2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Vegter S, Perna A, Postma MJ, et al Sodium intake, ACE inhibition, and progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23: 165–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Kwakernaak AJ, Waanders F, Slagman MC, et al Sodium restriction on top of renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system blockade increases circulating levels of N‐acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline in chronic kidney disease patients. J Hypertens 2013; 31: 2425–2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Eriguchi M, Bernstein EA, Veiras LC, et al The absence of the ACE N‐domain decreases renal inflammation and facilitates sodium excretion during diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018; 29: 2546–2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Nitta K, Nagai T, Mizunuma Y, et al N‐Acetyl‐seryl‐aspartyl‐lysyl‐proline is a potential biomarker of renal function in normoalbuminuric diabetic patients with eGFR >/= 30 ml/min/1.73 m(2). Clin Exp Nephrol 2019; 23: 1004–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Afkarian M, Zelnick LR, Hall YN, et al Clinical manifestations of kidney disease among US adults with diabetes, 1988–2014. JAMA 2016; 316: 602–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Kume S, Araki SI, Ugi S, et al Secular changes in clinical manifestations of kidney disease among Japanese adults with type 2 diabetes from 1996 to 2014. J Diabetes Investig 2019; 10: 1032–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]