Abstract

The genus Vibrio is ubiquitous in marine environments and uses numerous evolutionary characteristics and survival strategies in order to occupy its niche. Here, a newly identified species, Vibrio fujianensis, was deeply explored to reveal a unique environmental adaptability. V. fujianensis type strain FJ201301T shared 817 core genes with the Vibrio species in the population genomic analysis, but possessed unique genes of its own. In addition, V. fujianensis FJ201301T was predicated to carry 106 virulence-related factors, several of which were mostly found in other pathogenic Vibrio species. Moreover, a comparative transcriptome analysis between the low-salt (1% NaCl) and high-salt (8% NaCl) condition was conducted to identify the genes involved in salt tolerance. A total of 913 unigenes were found to be differentially expressed. In a high-salt condition, 577 genes were significantly upregulated, whereas 336 unigenes were significantly downregulated. Notably, differentially expressed genes have a significant association with ribosome structural component and ribosome metabolism, which may play a role in salt tolerance. Transcriptional changes in ribosome genes indicate that V. fujianensis may have gained a predominant advantage in order to adapt to the changing environment. In conclusion, to survive in adversity, V. fujianensis has enhanced its environmental adaptability and developed various strategies to fill its niche.

Keywords: Vibrio fujianensis, comparative genomics, transcriptomics, environmental adaptability, cross-agglutination reaction, salt tolerance

1. Introduction

The genus Vibrio is ubiquitous and abundant in oceanic, estuarine, and freshwater environments [1,2,3]. They are known to produce biofilm on the surface, and they either swim freely in marine water or adhere to/live associated with other organisms. More and more novel species have been scientifically identified, with more than 130 Vibrio species reported to date. Many Vibrio spp. are well-known bacterial pathogens, causing disease in humans or marine animals. Vibrio cholerae [4] is the causative agent of human epidemic cholera. Vibrio parahaemolyticus causes severe gastroenteritis in humans through consumption of contaminated seafood [5]. Some other Vibrio can also cause severe bacteremia, skin, and soft tissue infection [6].

In the process of evolution, Vibrio adapted to its environment in various strategies. Firstly, Vibrio can obtain a better survival ability in their environment by forming biofilm or growing rapidly to a certain population density. Many Vibrio isolates use population density to control the gene expression via a quorum-sensing system; for instance, the quorum-sensing transcription factor AphA directly regulates natural competence in V. cholerae [7]. V. cholerae also possesses multiple quorum-sensing systems that control virulence and biofilm formation among other traits [8]. Secondly, Vibrio spp. can develop adaptive strategies to survive in extreme conditions of salinity stress and temperature, such as the mechanism of osmoregulation and osmotic balance, modification of the lipid composition, activity of ion pumps, and increasing of the secondary metabolite production [9]. In addition, one of the adaptive strategies employed by various Vibrio spp. to survive in the changing environment is genetic variation via positional mutations or the horizontal transfer of foreign genes [10].

Vibrio fujianensis was recently identified as a novel Vibrio species; the type strain FJ201301T was isolated from aquaculture water in Fujian Province, China, in 2013 [11]. As a novel species, V. fujianensis has evolved many characteristics and survival strategies to occupy its niche. For instance, the strain of V. fujianensis is able to grow under a wide range of pH (pH 5–10) and salt concentrations (1%–10% w/v) [11]. In addition, the strain of V. fujianensis can result in a cross-agglutination reaction with the specific serum of V. cholerae O139 serogroup, which suggests the two species have a similar or the same O-antigen component. It is necessary to understand the evolutionary characteristics and genomic diversity of a new Vibrio species. In the present study, a comparative genomics analysis was performed based on the V. fujianensis draft genome and other reference genomes of the genus Vibrio. Two different salt stress conditions, 1% (w/v) and 8% (w/v), were selected for RNA-Seq-based transcriptome analysis. We investigated the comparative differentially expressed gene (DEG) profiles of V. fujianensis with low-salt or high-salt stress, so as to gain an increased understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the species’ environmental response.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strain Culture and RNA Preparation

V. fujianensis FJ201301T was used throughout this study. The strain was cultured as recommended for Luria-Bertani (LB, 3%, NaCl, w/v) agar at 30 °C for 18 h. The total RNA extraction from the two conditionally cultured strains was performed using the TRIZOL extraction reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), in accordance with the protocol mentioned before [12].

2.2. Genome and Transcriptome Sequencing

The whole genome sequence of V. fujianensis FJ201301T (accession number: GCA_002749895.1) was sequenced previously. In order to represent low-salt stress and high-salt stress, 1% and 8% (NaCl, w/v) concentrations were chosen, respectively. The RNA samples were extracted separately in each condition to measure them three times in duplicate. Transcriptome sequencing was performed using the Illumina HiSeq™ 2000 platform (San Diego, USA), with an average yield of 10.52 Mb raw data per sample. SOAPnuke software [13] was used to remove the adapters and low-quality reads in the sequencing data. Then, the filtered reads were compared to the reference genome using HISAT 2.1.0 software [14]. The whole RNA-sequencing process, including the RNA library construction, sequencing, and data pipelining, was done in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols by a commercial sequencing service (BGI, Shenzhen, China).

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was done using the 16S rRNA gene sequences and single-copy gene sequences. 16S rRNA gene sequences of 119 Vibrio bacteria and Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966T are available in the GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/; Table S1). The genetic distance and sequence similarity of the 16S rRNA genes were calculated with MEGA (version 7.0) [15] using Kimura’s two-parameter model. A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was reconstructed by MEGA software with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Gene prediction was performed using the prodigal tool in the prokaryotic genome sequences. Following the definition of a single-copy core gene by Fabini et al. [16], genes with a single-copy characteristic in each strain were identified as the core genes. After gene prediction from the genomes, CD-HIT (version 4.6.6, 2016) [17] was used to calculate a nonredundant homologous gene set. Next, we compared the coding genes of each strain with this nonredundant gene set using BLAST+ [18]. The core genome and the accessory genome were investigated in order to identify shared and unique genes, and to explain differences among several Vibrio species. The shared and unique genes in a Venn diagram were determined using BLASTn with an E-value cutoff of 1.0 × 10−5. The Venn diagram was reconstructed using R-3.5.2 [19]. DNA–DNA hybridization (DDH) values were computed using the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator v.2.1 [20]. The tools can be accessed from the following online resource: http://ggdc.dsmz.de/. The DDH values were calculated using the second formula. Genomes of V. fujianensis FJ201301T and other Vibrio species (Table S2) were used for phylogenetic analysis.

2.4. O-Polysaccharide (O-PS) Gene Cluster Analysis

The O-PS gene cluster sequence of V. fujianensis FJ201301T was aligned against that of V. cholerae O139 serogroup MO45. The genome region of Vibrio cincinnatiensis NCTC 12012T and V. metschnikovii JCM 21189T flanked by the rfaD and mutM genes was extracted from the draft genomes as the O-PS genetic region. The Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST; version 2.0) server pipeline [21] was used to predict the open reading frames (ORFs) and to annotate the ORFs of the O-PS gene cluster. Web-BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast) [22] was applied to the inferred putative functions. A comparative analysis of homologous regions of the Vibrio O-PS gene cluster was performed by Easyfig 2.2.3 software [23].

2.5. Virulence Gene Analysis

The Virulence Factors Database (VFDB) [24] (http://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/) was used to annotate the virulence genes. The virulence-related genes of the protein sequences were searched against the VFDB using BLAST+ [18].

2.6. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes

RSEM software (v1.2.8) [25] was used to calculate the gene expression level of each sample. The fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped (FPKM) method [26] was used to describe the transcript expression. A false discovery rate (FDR) [27] of <0.001 was used as the threshold p-value in multiple tests to judge the degree of difference in the unigenes expression. In a given RNA-sequencing library [28], the DEGs were defined with a cutoff p-value ≤0.001 and a ≥2-fold-change compared between two samples.

2.7. Transcriptome Data Analysis

The DEGs were annotated against the Swiss-Prot [29], Gene Ontology (GO) [30], and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases [31] by BLAST+ with an E-value cutoff of 1.0 × 10−5. The GO term functional analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis were performed in subsequent analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Evolutionary Position of V. fujianensis Species

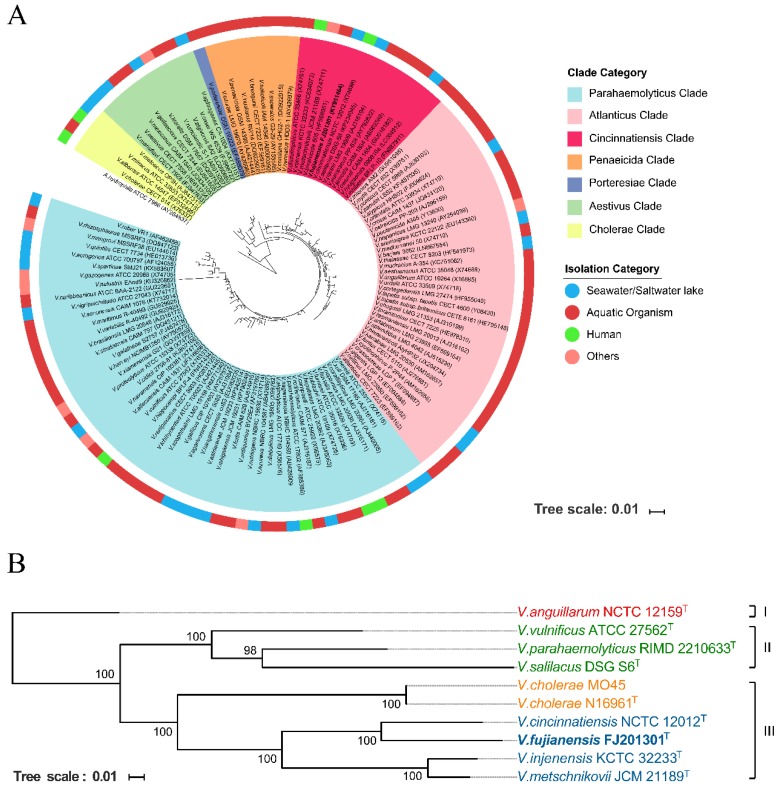

The 16S rRNA gene sequence of V. fujianensis FJ201301T was aligned and compared to a set of 119 corresponding sequences of other Vibrio species and strains. Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966T served as an outgroup species. A phylogenetic tree suggested that the Vibrio genus should be divided into seven different clades (Figure 1A). Highly consistent with our previous study [11], the novel V. fujianensis FJ201301T was classified as a member of the Cincinnatiensis clade; this clade also included other Vibrio species such as Vibrio cincinnatiensis NCTC 12012T, Vibrio metschnikovii JCM 21189T, Vibrio bivalvicida 605T, and Vibrio salilacus DSG-S6T.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of Vibrio fujianensis. (A) Phylogenetic tree among the genus Vibrio based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. (B) Phylogenetic tree based on homologous gene sequences of Vibrio species analyzed in this study. All single-copy homologous genes for each species were concatenated to form a new sequence 97,365 bp in length. The horizonal bar represents 0.01 substitution per nucleotide site. The accession numbers of 16S rRNA gene sequences and genomes are shown in Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

A phylogenetic tree based on single-copy homology genes (Figure 1B) showed that 10 strains were divided into three main groups, group I to group III. At the genome level, V. fujianensis FJ201301T was more closely related to V. cincinnatiensis NCTC 12012T, implying that they probably shared common ancestors in the past, according to the phylogenetic relationship. Compared with the 16S rRNA gene phylogenetic tree, the genetic relationship was slightly different. Here, V. salilacus DSG-S6T separated from the Cincinnatiensis clade, while the remaining Cincinnatiensis clade Vibrio spp. still gathered closely, which were divided into group III together with the V. cholerae strains. The DDH value(s) indicated that interspecies distinction among Vibrio species in the Cincinnatiensis clade was apparent (Table 1). The DDH values among these type strains were 18.70–65.90%. These DDH values were lower than the proposed cutoff value (70%) for species delineation [32], which confirmed that they represent different members of various genomic species. Likewise, the consistent results were indicated by average nucleotide identity (ANI) and average amino acid identity (AAI) analyses (data are not shown).

Table 1.

DNA–DNA hybridization (DDH) among Vibrio species of the Cincinnatiensis clade.

| Vibrio Species * | Vibrio Species * | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | |

| A | 100 | 20.30 | 19.50 | 29.60 | 18.90 | 22.20 | 19.00 | 21.70 | 19.50 | 21.70 | 20.20 | 20.30 |

| B | 100 | 19.40 | 19.80 | 26.50 | 21.50 | 21.50 | 20.80 | 21.50 | 21.30 | 19.10 | 19.30 | |

| C | 100 | 19.90 | 18.70 | 21.10 | 18.90 | 20.50 | 20.80 | 20.60 | 19.20 | 19.00 | ||

| D | 100 | 19.40 | 22.00 | 18.90 | 21.80 | 19.60 | 22.10 | 20.20 | 20.50 | |||

| E | 100 | 20.60 | 21.10 | 20.10 | 22.00 | 20.10 | 19.10 | 20.00 | ||||

| F | 100 | 20.90 | 54.00 | 22.30 | 35.30 | 21.00 | 21.50 | |||||

| G | 100 | 20.20 | 45.70 | 20.90 | 18.70 | 19.00 | ||||||

| H | 100 | 20.80 | 38.70 | 20.80 | 21.20 | |||||||

| I | 100 | 20.60 | 19.10 | 20.20 | ||||||||

| J | 100 | 20.60 | 21.30 | |||||||||

| K | 100 | 65.90 | ||||||||||

| L | 100 | |||||||||||

Vibrio species *: A. Vibrio bivalvicida 605T; B. Vibrio cincinnatiensis NCTC 12012T; C. Vibrio diazotrophicus NBRC 103148T; D. Vibrio europaeus PP-638T; E. Vibrio fujianensis FJ201301T; F. Vibrio hyugaensis 090810aT; G. Vibrio injenensis KCTC 32233T; H. Vibrio jasicida CECT 7692T; I. Vibrio metschnikovii JCM 21189T; J. Vibrio owensii CAIM 1854T; K. Vibrio pacinii DSM 19139T; L. Vibrio salilacus DSG S6T.

3.2. Population Genomic Analysis

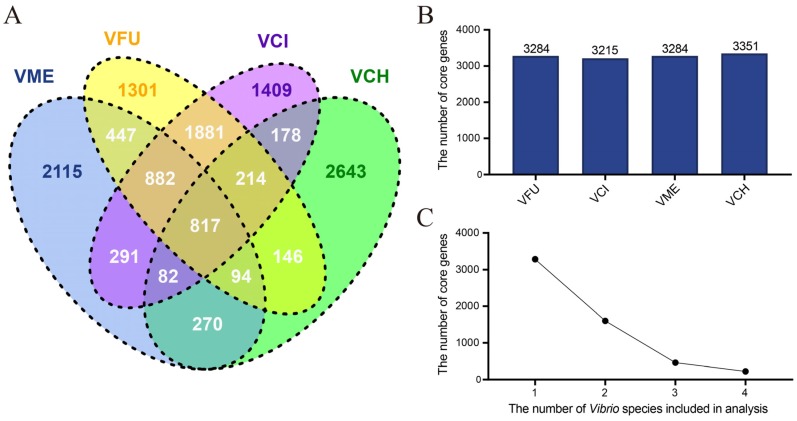

The pan-genome of the V. fujianensis FJ201301T, V. cincinnatiensis NCTC 12012T, V. metschnikovii JCM 21189T, and V. cholerae MO45 strains shared 817 core genes (Figure 2A), and these four genomes possessed 1301, 1409, 2115, and 2643 unique genes, respectively. An additional gene set, ranging from 178 to 1881, was shared by any two species, while the number of genes that were shared by any three species varied from 82 to 882.

Figure 2.

Comparative genomic analysis of Vibrio fujianensis and three other Vibrio species. (A) Venn diagram of the shared and unique genes found in V. fujianensis FJ201301T and three other Vibrio genomes. VME: V. metschnikovii JCM 21189T; VFU: V. fujianensis FJ201301T; VCI: V. cincinnatiensis NCTC 12012T; VCH: V. cholerae O139 serogroup MO45. (B) The number of core genes shared in V. fujianensis FJ201301T and three other Vibrio genomes. (C) Core gene quantitative trend. Vibrio species were added one by one for analysis in the following order (from 1 to 4): V. fujianensis FJ201301T, V. cincinnatiensis NCTC 12012T, V. metschnikovii JCM 21189T, and V. cholerae O139 serogroup MO45.

The numbers of core genes were calculated from the genomes mentioned above (Figure 2B). In terms of quantity, each Vibrio species contained more than 3000 core genes, and V. cholerae MO45 had slightly more genes than the other three bacteria. Coincidentally, both V. fujianensis FJ201301T and V. metschnikovii JCM 21189T had 3284 core genes. On the other hand, the decreasing trend (Figure 2C) became more apparent when the number of strains continued to increase.

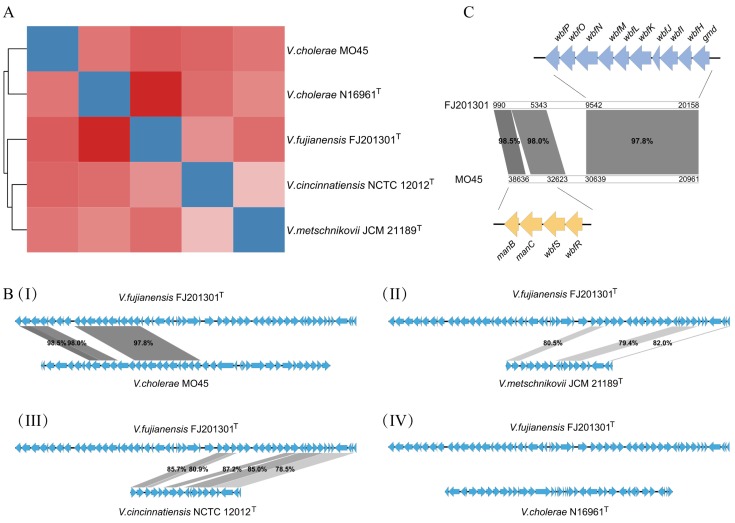

3.3. Comparative Analysis of O-PS Gene Cluster

The O-PS gene cluster analysis (Figure 3A) showed that V. fujianensis FJ201301T had a few sequence variations compared with V. metschnikovii JCM 21189T and V. cincinnatiensis NCTC 12012T, resulting in a single branch separately in the clustering analysis. A comparison of the O-PS genes distribution (Figure 3B) revealed the possible reason for this large variation. The O-PS gene cluster sequence of V. fujianensis FJ201301T is partially similar to the counterparts of V. metschnikovii JCM 21189T and V. cincinnatiensis NCTC 12012T. We found that the O-PS gene cluster of V. fujianensis had three homologous fragments shared with the same region of V. cholerae MO45 (the similarity was 98.5%, 98.0%, and 97.8%, respectively). The first two homologous regions contained four genes, namely, manB, manC, wbfR, and wbfS (Figure 3C), encoding phosphomannomutase, mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase, UDP-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase, and asparagines synthetase, respectively. The third region contained the gmd gene and nine other genes, namely, wbfH, wbfI, and wbfJ to wbfP (Figure 3C). Gene gmd catalyzed the conversion of GDP-D-mannose to GDP-4-dehydro-6-deoxy-D-mannose. The wbf family genes were likely to participate in the regulation of the cell wall biosynthesis, and may be involved in the maturation of the outermost layer of protein. In addition, considering the DNA GC content, the O-PS gene cluster had a GC content (40.9 mol%) lower than the genome average (43.4 mol%), while the homologous fragment (nucleotide site from 990 to 20,158) had a GC content of 38.2 mol%, which was far lower than the average GC content of the genome (data are not shown). This atypical GC content provided strong evidence that the homologous fragment had recently gone through a genetic recombination event, by horizontal gene transfer, with V. cholerae O139 serogroup strains, a different bacterial species in the long-term evolution.

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of O-polysaccharide (O-PS) gene cluster. (A) Clustering of O-PS gene cluster. (B) O-PS gene cluster comparison between V. fujianensis FJ201301T and other Vibrio species. I to IV show V. fujianensis vs. V. cholerae O139 serogroup MO45, V. metschnikovii JCM 21189T, V. cincinnatiensis NCTC 12012T, and V. cholerae O1 serogroup N16961T, respectively. (C) Homologous regions (nucleotide site from 990 to 20,158) of O-PS gene cluster between V. fujianensis FJ201301T and V. cholerae O139 serogroup MO45.

3.4. Prediction of Virulence-Associated Genes

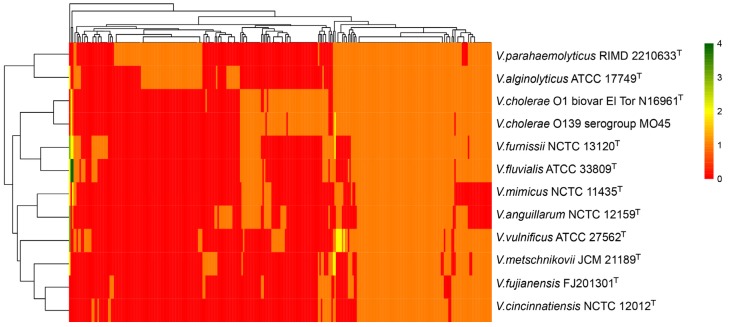

The virulence-associated factors of V. fujianensis FJ201301T and other common pathogens were predicted against the VFDB. A putative virulence-associated gene pool included a total of 281 kinds of virulence genes (Table S3), and approximately 37.7% of these genes were found in the V. fujianensis FJ201301T genome. V. fujianensis FJ201301T carried 17 kinds of potential virulence factors and 106 related genes (Table 2). The genes involved in mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin (MSHA), type IV pilus, flagella, and EPS type II secretion system were mostly found in V. fujianensis FJ201301T and pathogenic Vibrio species (Table S3). Cholera toxin ctxA, thermosolve hemolysin tlh/tdh, and other toxins (e.g., hlyA and rtxA/B) were not detected in V. fujianensis FJ201301T. The unknown protein related to O-antigen has been described only in V. fujianensis FJ201301T and in V. cholerae MO45 (Table S3). Moreover, V. fujianensis FJ201301T and V. cincinnatiensis NCTC 12012T were still the most similar in the aspect of the category and quantity of virulence factors (Figure 4). Thus, we suspected that the potential pathogenicity of V. fujianensis FJ201301T was due to multi-interaction with a variety of virulence factors.

Table 2.

Function and pathogenic role of the virulence factors of V. fujianensis FJ201301T.

| VF Class | Virulence Factors | Function and/or Pathogenic Role |

|---|---|---|

| Adherence | Accessory colonization factor | Signal transduction |

| Mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin (MSHA type IV pilus) | Pilus assembly and pathogenesis | |

| Type IV pilus | Motility, cell–cell adhesion, and pathogenesis | |

| LPS O-antigen | Undetermined | |

| The tad locus | Hydrolase and tRNA processing | |

| Antiphagocytosis | Capsular polysaccharide | LPS biosynthesis and metabolism |

| Chemotaxis and motility | Flagella | Flagellum biogenesis, motor activity, and pathogenesis |

| Iron uptake | Enterobactin receptors | Iron transport |

| ABC transport systems | ATPase activity and transport | |

| Vibriobactin biosynthesis | Catalytic activity and multifunctional enzyme | |

| Acinetobactin | Enzyme activity | |

| Quorum sensing | Autoinducer-2 | Lyase, autoinducer synthesis, and quorum sensing |

| Secretion system | EPS type II secretion system | Protein secretion and protein transport |

| Others | O-antigen | Undetermined |

| Endotoxin | LOS | Multifunctional enzyme and lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis |

| Invasion | Flagella | Hydrolase and chemotaxis |

| Regulation | Two-component system | Transcription regulation |

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional hierarchical clustering analysis of putative virulence-associated genes based on the Virulence Factors Database (VFDB). Pathogenic Vibrio species are shown in the column and virulence factors are shown in the row. Different colors represent the corresponding number of virulence factors.

3.5. Gene Expression Analysis

A comparative transcriptome analysis between the low-salt and high-salt condition was conducted so as to identify the genes involved in salt tolerance. A Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.754 was calculated to reflect the correlation of the unigenes expression between two samples. The length distribution of the transcripts is shown in supplementary Figure S1.

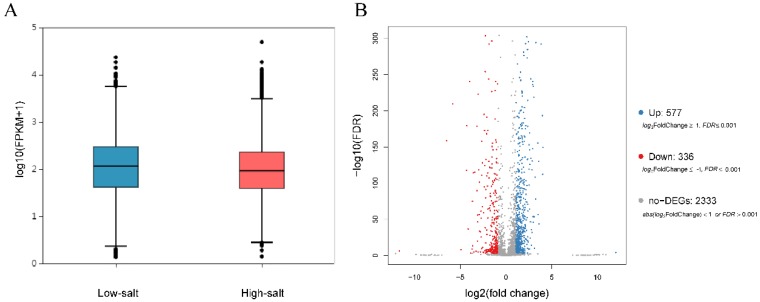

The box plot of the total gene expression (Figure 5A) showed the distribution and dispersion of the gene expression levels in two conditions. Comparing the relative transcript abundance in each unigene by using the FPKM, a total of 913 unigenes were found to be differentially expressed (Figure 5B); in a high-salt condition, 577 of these were significantly upregulated, whereas 336 unigenes were significantly downregulated. A cluster heatmap analysis of the DEG patterns is shown in supplementary Figure S2.

Figure 5.

Gene expression analysis. (A) Box plot of the total expressed genes evaluated by FPKM method in the low-salt or high-salt condition. (B) Volcano plot of the genes differentially expressed between the two samples. The blue and red colors represent upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively.

3.6. Annotation Analysis of DEGs

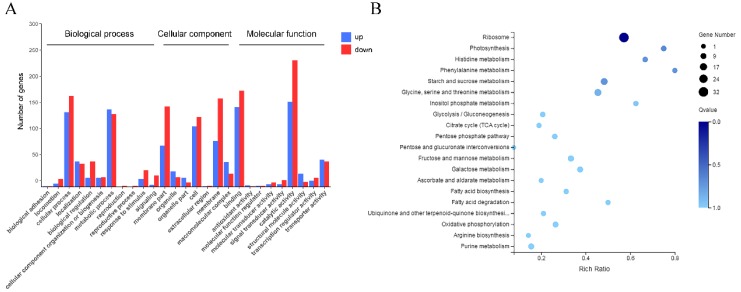

The GO annotation analysis (Figure 6A) categorized the DEGs into three modules, namely, biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. The GO terms predominantly enriched in the whole unigene pool were associated with molecular function, including “catalytic activity” for the first place, and “binding” ranked secondly (data are not shown). The top five GO terms mainly relevant for the upregulated DEGs contained “catalytic activity”, “binding”, “cellular process”, “membrane”, and “membrane part”. The downregulated genes group was largely associated with the terms “catalytic activity”, “binding”, “metabolic process”, “cellular process”, and “organic substance metabolic process” (data are not shown). The GO enriched bubble graph with the top 20 GO terms ranked by the smallest Q-value showed the different degrees of up- or downregulated DEGs enrichment from three dimensions (Figure S3). Notably, all of these DEGs significantly enriched the GO terms of “structural constituent of ribosome” and “ribosome”.

Figure 6.

(A) Gene ontology (GO) functional annotation analysis of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs). (B) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs between low-/high-salt condition. The bubble size indicates the number of genes, and the color shade represents the Q-value.

To get a further comprehensive understanding of the enriched metabolic or signal transduction pathways, we classified the DEGs in the KEGG pathways database for enrichment analysis (Figure 6B, top 20 terms ranked by the smallest Q-value). The KEGG pathway annotation classification of the DEGs between low-/high-salt environment is shown in Figure S4 in the Supplementary Material. As a result, “ribosome pathway” (ko03010) was of significance in the enrichment analysis (Q-value < 0.05).

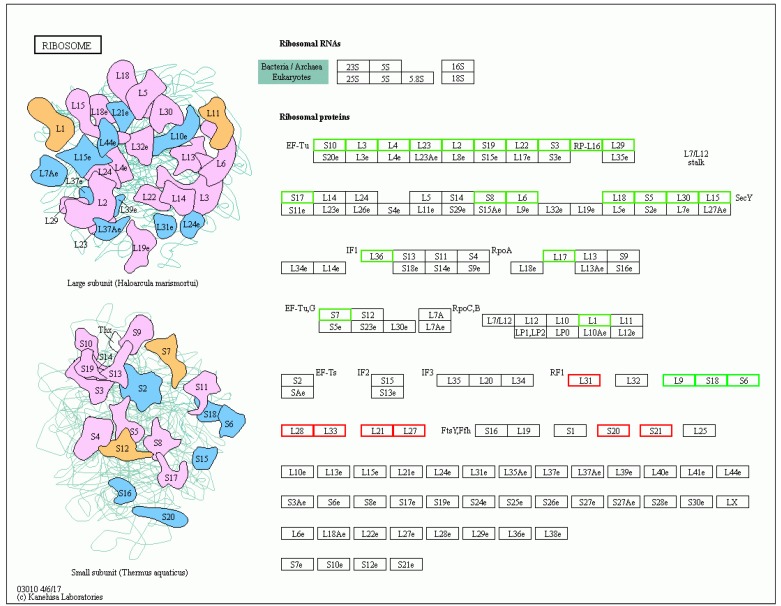

3.7. Key Genes under Salt Tolerance Response

The ribosome is described as a place for protein biosynthesis in cells and has a considerable influence on salt tolerance. There were 32 candidate genes found in the “ribosome pathway” (ko03010) that may participate in changes in the ribosome formation, eight of which were significantly upregulated, while the remaining 24 genes were significantly downregulated (Table 3 and Figure 7). Transcriptional changes in the ribosomal genes indicated that the V. fujianensis species responded efficiently and quickly to high-salt stress, which might be a predominant advantage in the changing environment.

Table 3.

Differentially expressed candidate genes involved in the ribosome pathway.

| Gene ID | Gene Alias | Substates | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | |||

| B7C60_RS02450 | rpmE | large subunit ribosomal protein L31 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS04755 | rpsT | small subunit ribosomal protein S20 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS05710 | rpmG | large subunit ribosomal protein L33 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS05715 | rpmB | large subunit ribosomal protein L28 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS11045 | rplU | large subunit ribosomal protein L21 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS11050 | rpmA | large subunit ribosomal protein L27 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS11455 | rpsU | small subunit ribosomal protein S21 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS12925 | rpmE | large subunit ribosomal protein L31 | Translation |

| Downregulated | |||

| B7C60_RS00940 | rplI | large subunit ribosomal protein L9 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS00945 | rpsR | small subunit ribosomal protein S18 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS00950 | rpsF | small subunit ribosomal protein S6 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS01530 | rplA | large subunit ribosomal protein L1 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS01740 | rpsG | small subunit ribosomal protein S7 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03490 | rplQ | large subunit ribosomal protein L17 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03515 | rpmJ | large subunit ribosomal protein L36 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03525 | rplO | large subunit ribosomal protein L15 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03530 | rpmD | large subunit ribosomal protein L30 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03535 | rpsE | small subunit ribosomal protein S5 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03540 | rplR | large subunit ribosomal protein L18 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03545 | rplF | large subunit ribosomal protein L6 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03550 | rpsH | small subunit ribosomal protein S8 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03575 | rpsQ | small subunit ribosomal protein S17 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03580 | rpmC | large subunit ribosomal protein L29 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03585 | rplP | large subunit ribosomal protein L16 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03590 | rpsC | small subunit ribosomal protein S3 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03595 | rplV | large subunit ribosomal protein L22 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03600 | rpsS | small subunit ribosomal protein S19 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03605 | rplB | large subunit ribosomal protein L2 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03610 | rplW | large subunit ribosomal protein L23 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03615 | rplD | large subunit ribosomal protein L4 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03620 | rplC | large subunit ribosomal protein L3 | Translation |

| B7C60_RS03625 | rpsJ | small subunit ribosomal protein S10 | Translation |

Figure 7.

Candidate unigenes related to salt tolerance. Red frames represent upregulated genes, while green frames represent downregulated genes.

4. Discussion

To date, more than 130 species are recognized in the genus Vibrio, many of which have been identified in recent years. It has been shown that the Vibrio genus is characterized by a remarkable biodiversity, having evolved to develop complex lifestyles. In this study, the phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences of 119 Vibrio species defined seven phylogenetic clades (Figure 1A). V. fujianensis FJ201301T was related to the Cincinnatiensis clade. In 2014, Michael et al. [33] used the multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) method to study the phylogenetic relationship and identification of 56 species in the genus Vibrio. At that time, V. cincinnatiensis and V. metschnikovii were classified as Cholerae clade with robust bootstrap values. However, in recent years, a considerable quantity of novel Vibrio species have been continuously identified and published, such as V. oceanisediminis [34] and V. injenensis [35], which have entered and broadened our horizon. Interpretation of bootstrap values makes these newly reported species separate from the Cholerae clade based on the phylogenetic tree. We propose that the Cincinnatiensis clade is an evolutionarily independent Vibrio clade that consists of these Vibrio species. V. fujianensis, as a novel species, is deemed to expand the species abundance and genetic diversity of the genus Vibrio.

A gene family is a group of genes derived from the same ancestor and consisting of two or more copies of a gene through gene duplication [36] and species divergence [37,38] in the biosphere. In most cases, structural genes are in a single-copy form in the bacterial chromosomal genome. V. cincinnatiensis and V. metschnikovii were recognized as two closest species of V. fujianensis. Great differences in the representative genomes of the four Vibrio strains (V. fujianensis FJ201301T, V. cincinnatiensis NCTC 12012T, V. metschnikovii JCM 21189T, and V. cholerae O139 serogroup MO45) were found, which somehow would cause differences in some aspects, like the GC content, genome structure, proportion of core genes and accessory genes. Each Vibrio strain contained a large number of strain-specific genes, which may be related to different strains inhabiting a limited host and environmental niche, or related to distinct types of diseases with different severity [39]. These strain-specific genes with an unequal number and diverse functions might confer several microbes some potential to go through environmentally troubled times [40,41].

Virulence-associated genes are believed to allow strains to carry adaptation and pathogenicity [42]. Studies of the virulence factor increasingly show the important role of virulence-associated genes in environmental adaptation. Virulence-related profile, including flagella, pili, and the two-component regulatory system, indicated the putative differentiation in niche and pathogenicity [38]. Meanwhile, the virulence genes were associated with environmental stress adaptation [43]. Virulence factors in M. tuberculosis were implicated in the adaptation of limited nutritional conditions in macrophages or for counteracting the microbicidal host cell responses, and M. tuberculosis EspC and EspA mutants have shown an inhibition of the bacterial growth or the biological metabolism [44]. In our study, the VFDB prediction result showed that the MSHA, type IV pilus, flagella, and EPS type II secretion system-related virulence genes were detected in V. fujianensis, and these genes were universally shared in common pathogenic Vibrio species. By assembling surface antigen structure [45], secreting virulence effect protein [46], and developing other lifestyles, bacteria become so powerful in order to escape the immune defense system in the host. Likewise, V. fujianensis has a strong adaptability to new environments. It carries a number of virulence-associated factors in the virulence-gene pool among pathogenic Vibrio Table 2 and Table S3, indicating that there may be an extensive gene swap or gene exchange between V. fujianensis and other pathogenic Vibrio.

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is considered to be an important mode of acquiring new genes and accelerating evolution. Mobile genetic elements, such as plasmids, phages (prophages), and integrons, are found to be a crucial factor for horizontal gene transfer, even contributing to the virulence and antibiotic resistance of Vibrio [47]. Recently, the authors [48] showed that genetic material via HGT promoted the environmental adaptability of pathogenic bacteria. Borgeaud et al. [49] have confirmed that in V. cholerae, type VI secretion system genes are coregulated with genes involved in exogenous DNA uptake. On the other hand, cases of serum cross-agglutination between different species are reported from time to time; a well-known example is the cross-reaction between E. coli and Shigella in Enterobacter species [50,51,52]. In our research, we found that the O-PS gene cluster of V. fujianensis FJ201301T and V. cholerae O139 serogroup MO45 shared highly homologous gene coding regions. This finding was a reasonable explanation for the cross-agglutination between V. fujianensis and V. cholerae O139 serum. With combined atypical GC content values, we propose that between the V. fujianensis FJ201301T and V. cholerae O139 serogroup MO45, a horizontal gene transfer of a partial O-PS gene cluster may have occurred. Sally et al. [53] demonstrated the adaptive role of modifications to the LPS structure (including loss of O-antigen expression) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa over the course of chronic respiratory tract infections. The O-antigen of V. cholerae is proven to play a role in critical defense by increasing drag force to impede attackers [54]. O-antigen is also the receptor of the V. cholerae specific typing phage [55]. Another research showed that the O-antigen in Vibrio species was associated with the specific environmental colonization ability [56], which can be beneficial to develop alternative lifestyles during intestinal colonization. Therefore, we consider that the exchange of partial O-antigen fragments between V. fujianensis FJ201301T and V. cholerae O139 can greatly enhance the environmental adaptability of V. fujianensis FJ201301T to quickly reproduce and tenaciously survive in nature.

Transcriptome changes for V. fujianensis in response to salt stress tolerance are mainly reflected in the molecular function represented by catalytic activity. Transcriptional changes involved in the carbohydrate metabolism, membrane transport, amino acid metabolism, and signal transduction were found to be important for the high salt stress in V. fujianensis. The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis considered the “ribosome pathway” (ko03010) as a significant enrichment; this result is consistent with the high-salt transcription and expression of Shewanella algae in our previous study [57]. Eiji et al. [58] found that the VemP-mediated regulation of SecDF2 was essential for the survival of marine bacteria when the Na+ concentration in the environment changed. Transcriptome research in response to salt stress in Betula halophila [59] showed that the top four enriched pathways were “fatty acid elongation”, “ribosome”, “sphingolipid metabolism”, and “flavonoid biosynthesis”; furthermore, the related transcription factor was analyzed by qRT-PCR in order to verify the important role in salt resistance in B. halophila. Proteomic analyses in C. albicans revealed a link between ribosomal gene expression and environmental adaptation [60]. Salt tolerance is a common feature of Escherichia coli, in which the maturation or function of the ribosome is impaired [61]. Changes in the ribosome confer salt resistance on some microbes [57,61]. Microbes begin to synthesize or uptake osmo-protectants in a high-salt condition, while inhibiting general σ70 transcription [62]. The Na+/H+ antiporter makes it effective for the survival of Vibrio species in a saline environment. NhaB has been proven to be a possible mechanism for regulating Na+/H+ antiporter activity [63]. To our knowledge, some microorganisms form a variety of biological mechanisms and physiological responses to high salt stress, and those mechanisms can help them take advantage of the unfavorable environments [9,64]. Marsden et al. [65] found that nutrient and salt availability may contribute to Vibrio biofilm formation. In general, microorganisms rely on a salt rejection strategy called osmoadaptation, which involves compatible solute accumulation, for example, the accumulation of K+ ions or some low molecular mass organic solutes. Usually, the formation of organic solutes makes conditions more favorable for the osmotic balance in cells, like sugar, alcohol, amino acid, and their derivatives [66]. In addition, mediation by the Na+/H+ antiporter is used to pump extra Na+ ions out of the cell to maintain a proper Na+ concentration in the cell. Fu et al. [57] also found that genes involved in peptidoglycan synthesis, DNA repair, tricarboxylic acid cycle, and the glycolytic pathway were the alternative emphasis of salt response mechanisms in Shewanella algae.

5. Conclusions

In this study, changes in the ribosome pathway may be related to salt tolerance via transcriptome sequencing. Strain-specific genes in the V. fujianensis species might help develop its innate adaptability, as well as its potential ability to evolve quickly and thrive in the ecological niche. Several genetic motility genes might be attributed to HGT in the evolutionary process.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/8/4/555/s1, Figure S1: Sequence length distribution of V. fujianensis transcripts analyzed in this study. Figure S2: Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) cluster analysis of gene expression patterns between the high-salt and low-salt condition. Figure S3: (A) Functional classification of gene ontology (GO) annotations of the up-regulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs). (B) Functional classification of GO annotations of the down-regulated DEGs. (C) Bubble charts of GO enrichment analysis of the up-regulated DEGs. (D) Bubble charts of GO enrichment analysis of the down-regulated DEGs. Figure S4: Functional classification of KEGG pathway of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Table S1: Overview of 16S rRNA gene sequences of Vibrio species analyzed in this study. Table S2: Genomic overview of Vibrio species analyzed in this study. Table S3: Virulence-associated factors profile of V. fujianensis and other pathogenic Vibrio species.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.W. and Z.H.; methodology, Z.H. and Z.L.; software, Z.H. and Z.L.; validation, H.D. and Z.H; formal analysis, D.W. and Z.H.; investigation, Z.H. and K.Y.; resources, D.W.; data curation, Z.H. and K.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.H. and Y.F.; writing—review and editing, D.W. and Z.H.; visualization, Z.H.; supervision, H.C., B.K., and Q.W.; project administration, D.W.; funding acquisition, D.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31570134) and the National Sci-Tech Key Project (2018ZX10102-001, 2018ZX10734404) from National Health Commission, China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Barbieri E., Falzano L., Fiorentini C., Pianetti A., Baffone W., Fabbri A., Matarrese P., Casiere A., Katouli M., Kuhn I., et al. Occurrence, diversity, and pathogenicity of halophilic Vibrio spp. and non-O1 Vibrio cholerae from estuarine waters along the Italian Adriatic coast. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65:2748–2753. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.6.2748-2753.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esteves K., Hervio-Heath D., Mosser T., Rodier C., Tournoud M.G., Jumas-Bilak E., Colwell R.R., Monfort P. Rapid proliferation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus, and Vibrio cholerae during freshwater flash floods in French Mediterranean coastal lagoons. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:7600–7609. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01848-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lovell C.R. Ecological fitness and virulence features of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in estuarine environments. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017;101:1781–1794. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clemens J.D., Nair G.B., Ahmed T., Qadri F., Holmgren J. Cholera. Lancet. 2017;390:1539–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freitas C., Glatter T., Ringgaard S. The release of a distinct cell type from swarm colonies facilitates dissemination of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in the environment. ISME J. 2020;14:230–244. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0521-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker-Austin C., Oliver J.D., Alam M., Ali A., Waldor M.K., Qadri F., Martinez-Urtaza J. Vibrio spp. infections. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2018;4:1–19. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haycocks J., Warren G., Walker L.M., Chlebek J.L., Dalia T.N., Dalia A.B., Grainger D.C. The quorum sensing transcription factor AphA directly regulates natural competence in Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1008362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bridges A.A., Bassler B.L. The intragenus and interspecies quorum-sensing autoinducers exert distinct control over Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation and dispersal. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallardo K., Candia J.E., Remonsellez F., Escudero L.V., Demergasso C.S. The Ecological Coherence of Temperature and Salinity Tolerance Interaction and Pigmentation in a Non-marine Vibrio Isolated from Salar de Atacama. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1943. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee S.K., Rutley R., Bussey J. Diversity and Dynamics of the Canadian Coastal Vibrio Community: An Emerging Trend Detected in the Temperate Regions. J. Bacteriol. 2018;200:e00787–e00917. doi: 10.1128/JB.00787-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang Y.J., Chen A.P., Dai H., Huang Y., Kan B., Wang D.C. Vibrio fujianensis sp. nov., isolated from aquaculture water. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018;68:1146–1152. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu X.P., Liang W.L., Du P.C., Yan M.Y., Kan B. Transcript changes in Vibrio cholerae in response to salt stress. Gut Pathog. 2014;6:47. doi: 10.1186/s13099-014-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cock P.J., Fields C.J., Goto N., Heuer M.L., Rice P.M. The Sanger FASTQ file format for sequences with quality scores, and the Solexa/Illumina FASTQ variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1767–1771. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim D., Langmead B., Salzberg S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orata F.D., Kirchberger P.C., Meheust R., Barlow E.J., Tarr C.L., Boucher Y. The Dynamics of Genetic Interactions between Vibrio metoecus and Vibrio cholerae, Two Close Relatives Co-Occurring in the Environment. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015;7:2941–2954. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu L.M., Niu B.F., Zhu Z.W., Wu S.T., Li W.Z. CD-HIT: Accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3150–3152. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Z.P., Pang B., Wang D.C., Li J., Xu J.L., Fang Y.J., Lu X., Kan B. Expanding dynamics of the virulence-related gene variations in the toxigenic Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1. BMC Genom. 2019;20:360. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5725-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walter W., Sanchez-Cabo F., Ricote M. GOplot: An R package for visually combining expression data with functional analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2912–2914. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Auch A.F., Klenk H.P., Goker M. Standard operating procedure for calculating genome-to-genome distances based on high-scoring segment pairs. Stand. Genom. Sci. 2010;2:142–148. doi: 10.4056/sigs.541628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aziz R.K., Bartels D., Best A.A., DeJongh M., Disz T., Edwards R.A., Formsma K., Gerdes S., Glass E.M., Kubal M., et al. The RAST Server: Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson M., Zaretskaya I., Raytselis Y., Merezhuk Y., McGinnis S., Madden T.L. NCBI BLAST: A better web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W5–W9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan M.J., Petty N.K., Beatson S.A. Easyfig: A genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1009–1010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu B., Zheng D.D., Jin Q., Chen L.H., Yang J. VFDB 2019: A comparative pathogenomic platform with an interactive web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D687–D692. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li B., Dewey C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mortazavi A., Williams B.A., McCue K., Schaeffer L., Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reiner A., Yekutieli D., Benjamini Y. Identifying differentially expressed genes using false discovery rate controlling procedures. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:368–375. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btf877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Podnar J., Deiderick H., Huerta G., Hunicke-Smith S. Next-Generation Sequencing RNA-Seq Library Construction. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2014;106:4–21. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0421s106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boutet E., Lieberherr D., Tognolli M., Schneider M., Bansal P., Bridge A.J., Poux S., Bougueleret L., Xenarios I. UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, the Manually Annotated Section of the UniProt KnowledgeBase: How to Use the Entry View. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016;1374:23–54. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3167-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaudet P., Dessimoz C. Gene Ontology: Pitfalls, Biases, and Remedies. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017;1446:189–205. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3743-1_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanehisa M., Sato Y., Morishima K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG Tools for Functional Characterization of Genome and Metagenome Sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 2016;428:726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meier-Kolthoff J.P., Klenk H.P., Göker M. Taxonomic use of DNA G+C content and DNA-DNA hybridization in the genomic age. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014;64:352–356. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.056994-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gabriel M.W., Matsui G.Y., Friedman R., Lovell C.R. Optimization of multilocus sequence analysis for identification of species in the genus Vibrio. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;80:5359–5365. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01206-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang S.R., Srinivasan S., Lee S.S. Vibrio oceanisediminis sp. nov., a nitrogen-fixing bacterium isolated from an artificial oil-spill marine sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015;65:3552–3557. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paek J., Shin J.H., Shin Y., Park I.S., Kim H., Kook J.K., Kim D.S., Park K.H., Chang Y.H. Vibrio injenensis sp. nov., isolated from human clinical specimens. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 2017;110:145–152. doi: 10.1007/s10482-016-0810-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maharjan R.P., Gaffe J., Plucain J., Schliep M., Wang L., Feng L., Tenaillon O., Ferenci T., Schneider D. A case of adaptation through a mutation in a tandem duplication during experimental evolution in Escherichia coli. BMC Genom. 2013;14:441. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shirai K., Hanada K. Contribution of Functional Divergence through Copy Number Variations to the Inter-Species and Intra-Species Diversity in Specialized Metabolites. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:1567. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hobbs M.M., Seiler A., Achtman M., Cannon J.G. Microevolution within a clonal population of pathogenic bacteria: Recombination, gene duplication and horizontal genetic exchange in the opa gene family of Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 1994;12:171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yin Z.Q., Yuan C., Du Y.H., Yang P., Qian C.Q., Wei Y., Zhang S., Huang D., Liu B. Comparative genomic analysis of the Hafnia genus reveals an explicit evolutionary relationship between the species alvei and paralvei and provides insights into pathogenicity. BMC Genom. 2019;20:768. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-6123-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirkup B.J., Chang L., Chang S., Gevers D., Polz M.F. Vibrio chromosomes share common history. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:137. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castillo D., Alvise P.D., Xu R.Q., Zhang F.X., Middelboe M., Gram L. Comparative Genome Analyses of Vibrio anguillarum Strains Reveal a Link with Pathogenicity Traits. Msystems. 2017;2:e00001–e00017. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00001-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwartz K., Hammerl J.A., Gollner C., Strauch E. Environmental and Clinical Strains of Vibrio cholerae Non-O1, Non-O139 from Germany Possess Similar Virulence Gene Profiles. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:733. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forrellad M.A., Klepp L.I., Gioffre A., Sabio Y.G.J., Morbidoni H.R., de la Paz S.M., Cataldi A.A., Bigi F. Virulence factors of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Virulence. 2013;4:3–66. doi: 10.4161/viru.22329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacGurn J.A., Raghavan S., Stanley S.A., Cox J.S. A non-RD1 gene cluster is required for Snm secretion in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;57:1653–1663. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin M.Q., Bachman K., Cheng Z., Daugherty S.C., Nagaraj S., Sengamalay N., Ott S., Godinez A., Tallon L.J., Sadzewicz L., et al. Analysis of complete genome sequence and major surface antigens of Neorickettsia helminthoeca, causative agent of salmon poisoning disease. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017;10:933–957. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zong B.B., Zhang Y.Y., Wang X.R., Liu M.L., Zhang T.C., Zhu Y.W., Zheng Y.C., Hu L.L., Li P., Chen H., et al. Characterization of multiple type-VI secretion system (T6SS) VgrG proteins in the pathogenicity and antibacterial activity of porcine extra-intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Virulence. 2019;10:118–132. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2019.1573491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deng Y.Q., Xu H.D., Su Y.L., Liu S.L., Xu L.W., Guo Z.X., Wu J.J., Cheng C.H., Feng J. Horizontal gene transfer contributes to virulence and antibiotic resistance of Vibrio harveyi 345 based on complete genome sequence analysis. BMC Genom. 2019;20:761. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-6137-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen J.Y., Liu C., Gui Y.J., Si K.W., Zhang D.D., Wang J., Short D.P.G., Huang J.Q., Li N.Y., Liang Y., et al. Comparative genomics reveals cotton-specific virulence factors in flexible genomic regions in Verticillium dahliae and evidence of horizontal gene transfer from Fusarium. New Phytol. 2018;217:756–770. doi: 10.1111/nph.14861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Borgeaud S., Metzger L.C., Scrignari T., Blokesch M. The type VI secretion system of Vibrio cholerae fosters horizontal gene transfer. Science. 2015;347:63–67. doi: 10.1126/science.1260064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Linnerborg M., Weintraub A., Widmalm G. Structural studies utilizing 13C-enrichment of the O-antigen polysaccharide from the enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli O159 cross-reacting with Shigella dysenteriae type 4. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;266:246–251. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grimont F., Lejay-Collin M., Talukder K.A., Carle I., Issenhuth S., Le Roux K., Grimont P.A. Identification of a group of shigella-like isolates as Shigella boydii 20. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007;56:749–754. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46818-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iguchi A., Iyoda S., Seto K., Ohnishi M. Emergence of a novel Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O serogroup cross-reacting with Shigella boydii type 10. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011;49:3678–3680. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01197-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Demirdjian S., Schutz K., Wargo M.J., Lam J.S., Berwin B. The effect of loss of O-antigen ligase on phagocytic susceptibility of motile and non-motile Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Immunol. 2017;92:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Duncan M.C., Forbes J.C., Nguyen Y., Shull L.M., Gillette R.K., Lazinski D.W., Ali A., Shanks R.M.Q., Kadouri D.E., Camilli A. Vibrio cholerae motility exerts drag force to impede attack by the bacterial predator Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4757. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07245-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu J.L., Zhang J.Y., Lu X., Liang W.L., Zhang L.J., Kan B. O antigen is the receptor of Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 El Tor typing phage VP4. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:798–806. doi: 10.1128/JB.01770-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Post D.M., Yu L., Krasity B.C., Choudhury B., Mandel M.J., Brennan C.A., Ruby E.G., McFall-Ngai M.J., Gibson B.W., Apicella M.A. O-antigen and core carbohydrate of Vibrio fischeri lipopolysaccharide: Composition and analysis of their role in Euprymna scolopes light organ colonization. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:8515–8530. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.324012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fu X.P., Wang D.C., Yin X.L., Du P.C., Kan B. Time course transcriptome changes in Shewanella algae in response to salt stress. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e96001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ishii E., Chiba S., Hashimoto N., Kojima S., Homma M., Ito K., Akiyama Y., Mori H. Nascent chain-monitored remodeling of the Sec machinery for salinity adaptation of marine bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E5513–E5522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513001112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shao F.J., Zhang L.S., Wilson I.W., Qiu D.Y. Transcriptomic Analysis of Betula halophila in Response to Salt Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:3412. doi: 10.3390/ijms19113412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jacobsen M.D., Beynon R.J., Gethings L.A., Claydon A.J., Langridge J.I., Vissers J.P.C., Brown A.J.P., Hammond D.E. Specificity of the osmotic stress response in Candida albicans highlighted by quantitative proteomics. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:14492. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32792-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hase Y., Tarusawa T., Muto A., Himeno H. Impairment of ribosome maturation or function confers salt resistance on Escherichia coli cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65747. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee S.J., Gralla J.D. Osmo-regulation of bacterial transcription via poised RNA polymerase. Mol. Cell. 2004;14:153–162. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakamura T., Fujisaki Y., Enomoto H., Nakayama Y., Takabe T., Yamaguchi N., Uozumi N. Residue aspartate-147 from the third transmembrane region of Na(+)/H(+) antiporter NhaB of Vibrio alginolyticus plays a role in its activity. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:5762–5767. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.19.5762-5767.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ito M., Morino M., Krulwich T.A. Mrp Antiporters Have Important Roles in Diverse Bacteria and Archaea. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:2325. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marsden A.E., Grudzinski K., Ondrey J.M., DeLoney-Marino C.R., Visick K.L. Impact of Salt and Nutrient Content on Biofilm Formation by Vibrio fischeri. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e169521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roberts M.F. Organic compatible solutes of halotolerant and halophilic microorganisms. Saline Syst. 2005;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1746-1448-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.