Abstract

Introduction

Dementia is on the rise in Canada and globally. Ensuring accessibility to diagnosis, treatment and management throughout the course of the disease is a very significant problem worldwide. In order to provide comprehensive care to patients and their caregivers, enhancing primary care-based dementia care is seen as the way forward. In many Canadian provinces various collaborative care models (collCMs) anchored in primary care to improve dementia care have been developed and implemented. The overall objective of our research programme is to identify key factors for the successful implementation of collCMs, and to facilitate dissemination and scale-up of dementia best practices.

Methods and analysis

We will use a convergent mixed-methods design. An observational study using chart review (2014–2016) and questionnaires (2014–2018; repeated in 2020) will measure application of guidelines and implementation of collCMs. This study will be complemented with a qualitative descriptive study using interviews (2017–2020) conducted in parallel. Quantitative and qualitative results will be further integrated using a matrix representing sites and findings. An integrated knowledge exchange strategy will ensure uptake by principal stakeholders throughout the research.

Ethics and dissemination

Our study has been approved by all relevant ethics committees. Our dissemination plan follows an integrated knowledge transfer strategy using provincial, national and international councils. We will present the results individually to the clinical sites and then to these councils. Our research will be the first provincial and cross jurisdictional evaluation of primary care models for patients living with dementia, providing evidence on the ongoing debate on the respective role of clinicians in primary care and specialists in caring for patients with dementia.

Keywords: primary care, dementia, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our programme is the first to examine multiple models for patients living with dementia in the primary care setting across different jurisdictions and by doing so we will identify key components of dementia care and successful implementation of collaborative care models (collCMs) for dementia.

We will look at collCM with different maturity and in different jurisdictions, which will make the comparison of the models challenging; however, we will rely on a descriptive qualitative study to inform stakeholders and given the breadth of the data collection and the triangulation of data, we will be able to obtain a good portrait of the implementation processes.

By understanding how the collCMs were developed, implemented and evolved over time, our research will provide insight and guidance on successful implementation of collCMs for dementia in Canada and internationally to facilitate dissemination and scale-up of dementia best practices.

Our cross-sectional, observational study design without a control group will allow us to assess association, not causality between quality of care and key components of the collCMs but will reflect a more pragmatic, real-world evaluation.

By using a mixed-methods design, we will understand the link between implementation strategies, characteristics of the models of care and quality of dementia care while considering multilevel factors, from the patients, to the clinicians, to the primary care organisations.

Introduction

The WHO reports that dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease and other major neurocognitive disorders,1 2 is perhaps the 21st century's most serious health challenge.2 Lack of accessibility to dementia evaluation, treatment and management throughout the course of the disease is a significant problem resulting in long waiting-lists, delayed diagnosis and late intervention.1 In turn, this leads to patient and caregiver uncertainty, inadequate support and increased burden on caregivers.1 Timely diagnosis at the appropriate level in the healthcare system is increasingly important. In order to provide comprehensive care to patients and their caregivers, collaboration between physicians, nurses, other allied healthcare professionals and various community partners is essential.3

To deal with this issue in Canada, four Canadian Consensus Conferences on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia (CCCDTD)4 between 1989 and 2012 have made a series of recommendations and guidelines, that promote detection, diagnosis, treatment, management and coordination of care of patients living with dementia should be primarily the responsibility of the primary healthcare.

However, primary healthcare is not yet fully prepared to deal with patients with dementia.5 It is thus essential to increase the capacity of primary healthcare clinicians to care for this population and to better coordinate care between primary healthcare, memory clinics and community organisations (eg, the Alzheimer Society, home-based nursing services and home care services).

To this end, several Canadian provinces have made considerable efforts to develop and implement collaborative care models (collCMs) leveraging on the existence of interdisciplinary primary care teams.6–11 CollCMs specific to dementia care have been implemented at different levels across Canadian jurisdictions.

These primary care-based collCMs share the same visions and objectives, which are described in online supplementary file 1. Overall, they aim to provide timely, patient-centred, comprehensive and continuous interprofessional care for persons with dementia, including health promotion, detection, diagnosis, treatment, management and coordination of care throughout the course of the disease using standardised clinical tools. This could be achieved through collaboration between family physicians, nurses and other healthcare professionals working in Family Medicine Groups or Family Health Teams (FMGs/FHTs) along with their community partners and specialists as needed. Primary healthcare teams are becoming the hub of integrated care, where specialised services support primary care professionals in managing this complex population. However, the characteristics of these models, such as the processes and activities performed for persons with dementia and their caregivers, varies from one FMG/FHT to another. These interventions have shown promising results in terms of feasibility, clinician participation and satisfaction.6–8

bmjopen-2019-035916supp001.pdf (52.7KB, pdf)

The implementation of collCMs in Canada represents natural experiments, offering opportunities to evaluate innovative approaches and to identify determinants of better quality of care for patients with dementia.

The overall objective of our research programme is to identify key factors for the application of recommendations for dementia care and successful collCM implementation, and to facilitate dissemination and scale-up of dementia best practices. Our programme will be the first provincial and cross-jurisdictional evaluation of primary care collCMs for patients living with dementia.

The specific objectives are:

To determine the association between potential key factors (organisational characteristics and clinician characteristics) and outcomes of successful dementia management in primary care: quality of care, continuity of care and medications management

To examine how collCMs have been developed and implemented and have evolved over time to improve care of patients with dementia and their caregivers

To understand the link between implementation strategies, characteristics of collCMs and quality of dementia care.

Methods

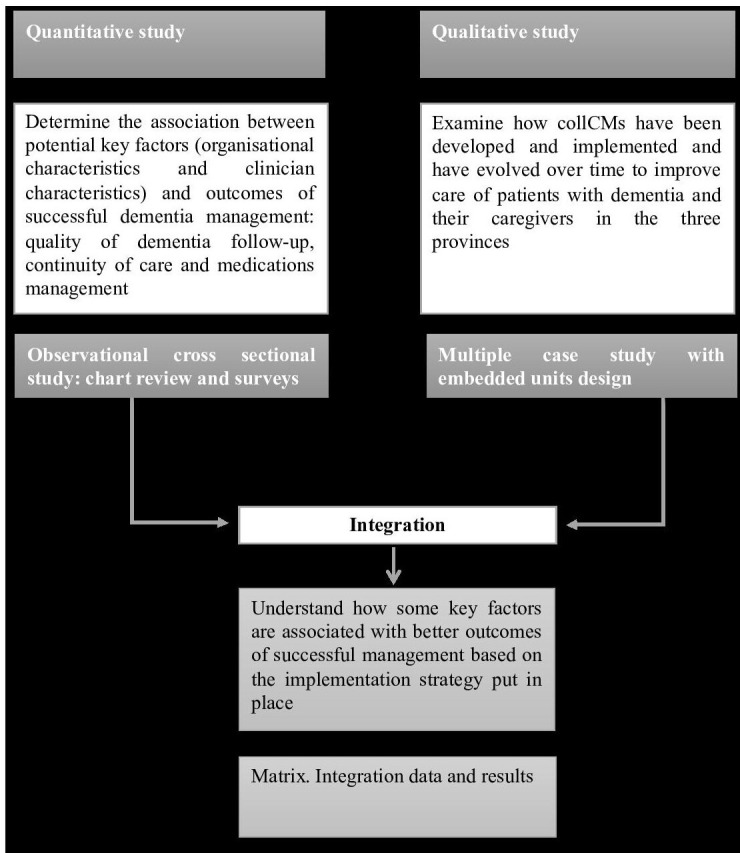

To reach our objectives, we will use a convergent mixed-methods design12 : a quantitative observational study using chart review and questionnaires to answer objective 1, and a qualitative descriptive study using interviews to answer objective 2. The results from both studies will be conducted in parallel and further integrated to answer objective 3.

Patient and public involvement

Our research programme employs an integrated knowledge exchange strategy,13 with decision-makers/managers, clinicians and patients/caregivers representatives throughout the entire study (figure 1). These stakeholders were involved in defining the research questions and study design via a series of meetings using an organisational participatory approach.14 They will further be involved in interpretation of results and dissemination of study results.

Figure 1.

Flowchart representing the research programme design. collCMs, collaborative care models.

Observational study

Main objective

To determine the association between potential key factors (organisational characteristics and clinician characteristics) and outcomes of successful dementia management in primary care: quality of dementia care, continuity of care and medications management.

Site selection

To purposively identify FMGs/FHTs who have implemented collCMs, we contacted researchers, clinicians and decision-makers in gerontology, geriatrics and primary care at the provincial and federal levels through our professional contact lists and during national conferences. We selected sites from three provinces (Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick), with various collCMs and levels of implementation to maximise the diversity of collCM characteristics.

Design

This is an observational study with a cross-sectional design using a chart review and questionnaires. A chart review was conducted for patients 75 years old and older with a diagnosis of dementia. We chose 75 years old as the age cut-off since dementia is highly prevalent in this population,15 thus increasing the number of eligible charts. One retrospective chart review was conducted in each site. The study period is 9 months, either from 1 October 2014 to 1 July 2015 or 1 October 2015 to 1 July 2016. The target population is all patients 75 years old and older with a diagnosis of dementia who had at least one visit to the site during the study period. Questionnaires were sent to the medical directors and clinicians from each site between 2014 and 2018 to be completed within 1 year of the site’s chart review.

Chart review

Outcomes

The primary outcome for the observational study is the quality of dementia care. Because no such measure exists, we developed our own Quality of Dementia Follow-Up Score, based on the recommendations and guidelines from a number of expert groups, such as Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders-3 (ACOVE-3),16 17 CCCDTD4 and others sources.9 18 This score is comprised of 10 indicators of quality of follow-up for dementia and has been further validated in a pilot study (table 1).19 These indicators were selected by our researchers and experts in dementia based on their concordance with Canadian clinical recommendations4 and their feasibility to be measured through a chart review. Patient’s eligibility for each indicator was assessed over the patient’s entire medical chart. Based on the validated ACOVE approach, a score will be calculated for each patient by summing the number of indicators performed during the study period by the FMGs/FHTs divided by the number of eligible indicators for that patient.

Table 1.

Summary of variables included in the analyses for the observational study with data source

| Type | Variable | Description | Chart review 2014–2016 | Organisational questionnaire 2016–2018 |

Clinicians’ questionnaire 2014–2017 |

| Primary outcome | Quality of dementia follow-up | 10 ACOVE indicators: Cognitive testing, functional status, behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, weight, caregiver needs, driving status, home care needs, community service needs (eg, Alzheimer Society), absence of anticholinergic medication and management of dementia medications19 |

X | ||

| Secondary outcomes | Continuity of primary care | Number of visits to the FMGs/FHTs; the number of notes, whether or not they were related to dementia, recorded in the charts by the FMG/FHT health professionals; the proportion of patients who have at least two visits to any clinician in the same FMG/FHT during the time period | X | ||

| Medications management | Proportion of patients with dementia who are treated with dementia medication such as cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine; the proportion of new dementia medications prescribed or initiated; the proportion of new dementia medications initiated by family physician; the proportion of new dementia medications initiated by specialists; and the proportion of patients who are treated with antipsychotics during the period | X | |||

| Explanatory variables | Organisational Best Practices for Dementia Score | See Henein et al.

23

Domains include: leadership within the interdisciplinary primary care clinic, financial support, support from cognition specialists, training, clinical information systems, coordination and continuity within the interdisciplinary primary care clinic, caregiver support and involvement, access to and coordination with home and community services, coordination with hospital |

X | ||

| Index of Conformity to an Ideal Type of primary care setting | See Levesque et al.

24

Domains include: vision, structure, resources, practice |

X | |||

| Clinician KAP Scores | See Arsenault-Lapierre et al.

26 27

Physicians’ and nurses’ perceived competency and knowledge related to dementia; the physicians’ and nurses’ attitudes towards dementia; the physicians’ practices in terms of cognitive evaluation; the physicians’ attitude towards their collaboration with other FMGs/FHTs healthcare professionals; and the nurses’ satisfaction with the support from secondary and tertiary care services and the physicians’ and nurses’ attitudes towards the collCMs |

X | |||

| Confounders | Patients’ characteristics | Age, sex, comorbidities (number of medications) | X | ||

| FMGs/FHTs demographic information | Number of registered patients, public/private, proximity to memory clinic, university affiliation, rural/urban and socio-economic area based on the FMGs/FHTs postal code, percentage of older patients | X |

ACOVE, Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders; collCMs, collaborative care models; FHT, Family Health Team; FMG, Family Medicine Group; KAP, knowledge, attitudes and practice.

We will also examine two secondary outcomes: (1) continuity of primary care for patients with dementia (including the number of visits to the FMGs/FHTs; the number of notes, whether or not they were related to dementia, recorded in the charts by the FMGs/FHTs health professionals; the proportion of patients who have at least two visits to any clinician in the same FMG/FHT during the study period); and (2) medications management (including proportion of patients with dementia treated with dementia medications such as cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine; proportion of new dementia medications prescribed or initiated; proportion of new dementia medications initiated by family physician; proportion of new dementia medications initiated by specialists; and proportion of patients treated with antipsychotics during the study period).

Patient characteristics

The age, sex, type of dementia, living status and comorbidities of each patient were collected through the chart review. The number of medications was used as a proxy for comorbidities.20

Data collection procedure

Patient charts were randomly selected among a list of registered patients 75 years and older with a dementia diagnosis. Data were collected by research assistants from patients’ charts in a customised and secure, web-based database. An instruction manual for assessing each indicator that needed to be collected through the chart review was prepared and tested. To further ensure the quality of the data collection, all the research assistants who reviewed patient charts were trained by a single supervisor, a research nurse, who answered any questions that arose throughout the chart review process.

Organisational questionnaire

Our organisational questionnaire has two parts. The first part assesses the adherence to various components of dementia care recommendations in each site. We adapted a questionnaire developed to assess the implementation of chronic care model in an US patient-centred medical home, the PCMH-A questionnaire,21 to the Canadian context using the Canadian recommendations on dementia.22 An overall score, called the Organisational Best Practices for Dementia Score ranging from 1 to 100 will be derived from the questions, where a higher score signifies better adherence to best practices according the recommendations.23

The second part of the questionnaire assesses site demographic information (table 1) and primary care organisational site characteristics. We adapted a validated questionnaire developed by the Institut national de santé publique du Québec24 to the Canadian context. From this questionnaire with four domain scores (structure, vision, resources and practice), we will derive a score called the Index of Conformity to an Ideal Type of primary care setting (ICIT), where a higher score indicates a better organised primary care setting (eg, higher full-time equivalent physicians, access to electronic medical records, after-hours care, etc).24

Content validity of our organisational questionnaire has been conducted with 8 experts and 11 medical directors across the three provinces and described elsewhere.23 Our questionnaire was developed in French and later translated into English and back translated into French to ensure equivalency between the two versions. Our organisational questionnaire was mailed in 2016–2018 to the medical directors at each site, along with two copies of the consent forms and a prestamped envelope. Multiple reminders were made to increase the completion rate. Data were entered by a research assistant and 10% of questionnaires were checked for reliability of data entry.

Clinicians’ questionnaires

Two clinicians’ questionnaires, one for the physicians/nurse practitioners (NPs) and one for the nurses and other healthcare professionals working in the participating FMGs/FHTs, will be used to assess their knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP)25 towards dementia care and towards the collCMs.26 27 Both questionnaires have 83 questions, including demographic questions. From these questionnaires, nine Clinician KAP Scores are calculated: the physicians/NPs’ and nurses’ perceived competency and knowledge related to dementia; their attitudes towards dementia care and their attitudes towards the collCMs; the physicians’ practices in terms of cognitive evaluation; the physicians’ attitude towards their collaboration with other FMGs/FHTs healthcare professionals; and the nurses’ satisfaction with the support from secondary and tertiary care services.

Both questionnaires have been developed and validated and are available in French and in English.26 27 The questionnaires were distributed to every family physician, NP and nurse practicing at participating sites in 2014–2017. Multiple reminders were made to increase the completion rate. Data were entered by a research assistant and 10% of questionnaires were checked for reliability of data entry.

Explanatory variables

Explanatory variables in this study will be the scores derived from the organisational and clinician questionnaires; specifically, the Organisational Best Practices for Dementia Score, ICIT score and Clinician KAP scores.

Analysis

Descriptive analyses

A descriptive summary of all study variables (outcomes, explanatory variables, patient and site characteristics) will be conducted overall and by site. For continuous variables, means and SD will be used for normally distributed variables; medians and interquartile ranges will be used for skewed variables. For binary or categorical variables, proportions will be reported.

Statistical modelling

Modelling for primary outcome: quality of dementia follow-up score

To determine the association between the organisational and clinician scores with the quality of dementia follow-up, we will construct a linear mixed-effects model using the data collected through the chart review, organisational and clinician questionnaires and site demographic information. The unit of analysis will be the patient. The site ID will be treated as random effect in the model, which will account for the clustering of patients within FMG/FHT. All other independent variables will be treated as fixed effects. Independent variables will include the explanatory variables (Organisational Best Practices for Dementia and Clinician KAP scores). The model will also adjust for potential confounding variables including patient characteristics (age, sex, number of medications) and FMGs/FHTs demographic characteristics (number of registered patients, public/private, proximity to memory clinic, university affiliation, rural/urban based on the FMGs/FHTs postal code, percentage of older patients). See table 1 for a summary of the variables.

Modelling for secondary outcomes

Similar models will be constructed to explore the association between the explanatory variables (Organisational Best Practices for Dementia, ICIT score and Clinician KAP scores) and the secondary outcomes (continuity of care and medications management) from the chart review while controlling for the same site-level and patient-level characteristics.

Sample size and power determination

We based the sample size and power calculation for this study on the primary outcome of quality of dementia follow-up. As the study was not powered on the secondary outcomes, analyses for secondary outcomes will be considered exploratory in nature. Statistically significant findings for secondary outcomes will be interpreted as hypothesis generating.

To maximise our effective sample size, we strove to maximise the number of FMGs/FHTs that could be included in the study based on time and budget constraints while also ensuring that an adequate effect size for the statistical models could be detected. With these constraints in mind, we determined that we would be able to include 28 sites in the study. Using an estimated intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.16 based on our pilot data, we established that 30 patients from each site would allow us to detect a small effect (Cohen’s f 2=0.05) due to a single factor, with 80% power. This effect size corresponds to an R2=.038, meaning that we could detect explanatory variables that account for at least 3.8% of the variability in the dementia follow-up scores. Thus, the number of patients required for this study was calculated to be 28 sites × 30 charts=840 patients.

Implementation study

Main objective

To examine how collCMs have been developed, implemented and evolved over time to improve care of patients with dementia and their caregivers in Canada.

Design

We use a qualitative descriptive design.28 A qualitative descriptive design is appropriate when the aim is to provide an in-depth description of a phenomenon, and when the phenomenon is of particular relevance to clinicians and policymakers.28

Sites selection

From the 28 sites selected in the observational study, 22 sites were sampled according to a purposeful maximum variation sampling method based on the type of collCMs and rural/urban location.

Data sources and target populations

Two sources of data will be used on different target populations.

Organisational questionnaire

The data collected from the organisational questionnaire will provide descriptive information about each primary care site including the patient population, human resources and funding model, thus providing important contextual information (see Observational study section). Primary care sites will be asked to complete the organisational questionnaire again in 2020 to determine any changes in these categories.

Interviews

In-depth semistructured interviews29 will provide the primary source of data for the implementation study.

Interviews were conducted in 2017 and 2019 with three clinicians (one family physician, one nurse and one other health professional) involved in delivering care and with one leader who implemented the collCM within each site. In addition, interviews will be conducted in both 2017 and 2020 with at least one representative from each provincial Ministry of Health including project managers. In 2019, interviews with two patients from each FHT/FMG were conducted. Physicians identified patients who were capable to participate in an interview, and for whom participation in an interview would not be detrimental to the patient (eg, it would not cause undue stress or anxiety). This determination was based on the physician’s clinical expertise and knowledge of the patient. If the patient preferred, interviews were conducted together with their family/friend caregiver. Patients and caregivers were asked about their experiences with the collCMs in their FHTs/FMGs (ie, what they enjoyed/found helpful about their experience, what they have not enjoyed/not found helpful and how their experience could be improved). We interviewed a convenient sample of physicians, nurses and other professionals involved in the day-to-day work. Interviewing this broad range of individuals will enable all aspects of the models to be examined and ensure that all components of the specific objectives will be addressed. The data collection timeline is described in table 2.

Table 2.

Data collection timeline for implementation study

| Data source and target population | Date |

| Organisational questionnaire | 2016–2018; repeated 2020 |

| Interviews with patients | 2019 |

| Interviews with Ministry of Health | 2017 and 2020 |

| Interviews with clinicians | 2017 and 2019 |

Overall, there will be a total of 201 interviews conducted. Interview guides have been developed based on previous work conducted by our team (not yet published). The interviews will be conducted mainly by phone for the clinicians, managers and government representatives, and in person (eg, at home) for patients. All the interview guides will be pilot tested for refinement and validation.

Analysis

Interviews will be transcribed and entered into NVivo V.12. Responses to open-ended questions from the organisational questionnaire will also be entered into NVivo V.12 to allow for analysis of all of the qualitative data. Data will be analysed using conventional content analysis.30 31 Interview transcripts will be independently coded by two team researchers, who will compare codes to agree on a codebook for the remaining transcripts. Codes will be collapsed into meaningful themes.

Using the theoretical framework of cocreation of innovation in healthcare3 we will assess:

The theoretical basis for the model (objectives, vision, mechanisms of action, target population, etc) and its components presently implemented (actions; material, financial and human resources; organisational structure; clinical interventions; timeline; frequency of the actions).

Components of the collCMs already in place and those still to be implemented; factors at the provincial, organisational, clinical team and community levels that can explain variations in the extent of implementation.

Barriers/facilitators to scale-up: factors that will be considered in this part of the analysis will include strategy of change management, resource mobilisation, training, leadership and the role of champions. Data from interviews will be used in this part of the analysis.

Results from this analysis will not only reveal the common processes through which collCMs are cocreated but will also explain how models have been tailored to meet the needs of the local partners and contexts.

Strategies to enhance rigour

Several strategies will be used to enhance rigour. First, an audit trail of analytical decisions will be kept using ‘memoing’ in NVivo. Second, triangulation of data sources and researchers will be carried out. Triangulation enhances the validity of the findings and also provides a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon being studied. Triangulation of data sources included the use of interviews with multiple groups (clinicians, patients and caregivers, policymakers) as well as the organisational questionnaire. Triangulation of researchers included having multiple researchers involved in coding an interpretation of the interview transcripts.

Integration of the implementation and the observational studies

To understand the link between implementation strategies, characteristics of models of care and quality of dementia follow-up (objective 3), the data and results from both studies will be integrated, which will provide a rich portrait at the site level.12 We will merge qualitative and quantitative data to compare them. We will develop a full data profile for each site, allowing the joint review of both data types by creating a new dataset.32 First, for the quantitative data, a table of variables for each FMG/FHT will be developed and compared with the overall results across sites. Second, for the qualitative data, summaries of facilitators and barriers for the successful implementation of collCMs will be developed for each FMG/FHT. Third, these data will be integrated using a matrix,12 whereby the columns will represent sites and rows will represent findings. This will allow us to draw conclusions on the link between implementation strategies, characteristics of models of care and quality of dementia follow-up.

Ethics and dissemination

This study is conducted using the principles of integrated knowledge transfer.33 Much of this work is completed through three active councils: a Provincial Council with partners in the three provinces where we collect data, a Canadian Council with stakeholders across all provinces and an International Council with researchers from many middle-income and high-income countries (the Netherlands, the USA, Mexico, the UK, France, Israel, China, Japan and Pan American Health Organisation/WHO). Our dissemination plan includes the following steps. First, we will present clinical sites with their individual results. Second, we will present results to our councils in order to understand the successful elements that build capacity in primary care to support the care of persons with dementia, to allow the different provinces to share successful elements of their Alzheimer plans and strategies, and finally to ensure dissemination and implementation of best practices across Canada and internationally.

Our results will also be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, conference presentations, social broadcast and print media. Authorship will be determined based on the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors recommendations.

This multicentre study has received Research Ethics Board (REB) approval from the Centre Intégré Universitaire de Santé et de Service Social (CIUSSS) du Centre-Ouest-de-l'île-de-Montréal and from each Centre Intégré de Santé et de Service Social or CIUSSS involved in Quebec, from the REB at the University of Waterloo, and from the REB from Université de Moncton and both regional health boards in New Brunswick. Amendments to the protocol will be communicated to all the REB involved and to all regional sites. In addition, each site will give their approval to participate in the study. The director of each site will grant our team permission to access patients’ charts. All individuals completing the questionnaires and individual face-to-face interviews will sign a consent form prior to participating (online supplementary file 2). The patients’ capacity to consent was evaluated by the clinicians and research team. Personal information for the patient’s charts (file number) was collected but will not be shared with the research team and will be kept for 10 years at the sites. Names of clinicians and medical directors from the sites were collected to ensure high completion rate but will be kept separately from the dataset.

bmjopen-2019-035916supp002.pdf (139.5KB, pdf)

Discussion

Ensuring accessibility to diagnosis, treatment and management throughout the course of dementia is a very significant challenge worldwide. In order to provide comprehensive care to patients and their caregivers, enhancing primary care-based dementia care is the way forward.

Our programme is the first to examine multiple models for patients living with dementia in the primary care setting across different Canadian jurisdictions. It will allow us to identify key factors for good quality of care, as reflected by the application of guidelines, and successful collCM implementation strategies.

Our study programme will provide valuable information for other Canadian jurisdictions interested in implementing a collCM. It will provide important and actionable results to provide transformative change both at the local and national levels. The results will be used to support the dissemination and scale-up of best dementia primary care practices. This study will produce timely and rigorous measures of quality of care in primary dementia care and its determinants. The results of this study will be used to refine the development of the National Strategy for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias Act in Canada.34 We work closely with the Canadian Academy of Health Science, which was mandated by the Minister of Health of Canada through the Public Health Agency of Canada, to provide an evidence-informed assessment on the state of knowledge to help develop the national strategy.35

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Research on Organisation of Healthcare Services for Alzheimer’s Canadian Team for Healthcare Services/System Improvement in Dementia Care—Phase 1 is composed of the coprincipal investigators (Howard Bergman from McGill University, Isabelle Vedel from McGill University, Paula Rochon from Women’s College Research Institute, Carrie McAiney from University of Waterloo, Yves Couturier from University de Sherbrooke, Sarah Pakzad from Université de Moncton, Susan Bronskill Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Erin Strumpf from McGill University, and Tibor Schuster from McGill University).

Footnotes

Twitter: @IsabelleVedel, @GenevieveArsen0, @godarsebillotte, @nadiasourial, @howardbergman2

Collaborators: Research on Organization of Healthcare Services for Alzheimers Team: M Aubin; R Borges da Silva; E Kroger; D St-Laurent; V Emond; P Bourque; G Anderson; M Wilchesky; D Gagnon; C Rodriguez; L Lee; P Baxter; S Kaasalainen; S Dupuis; L Lapointe; V Khanassov; J Ingram; D Seitz; M Pépin; M Guillette; N Dame; F Siméon; N Nicol-Clavet; M Hardouin; M Henein; L Vaillancourt; M LeBerre; R Rupp; M Gueriton; D Huntsbarger; S Burns; S Bronskill; E Strumpf; P Rochon; T Schuster; P Jarrett.

Contributors: IV, CM, YC, SP, GA-L, NS, CG-S, RS and HB made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the study and drafting the manuscript. All other authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

Funding: The pilot study, the development and validation of questionnaires and this study are funded by two operating grants: Pfizer - Fonds de recherche Québec Santé (FRQS) – Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux (2013–2016 #28859) and the Canadian Consortium for Neurodegeneration and Ageing (CCNA 2014–2019). The Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Ageing is supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research with funding from several partners.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

Research on Organization of Healthcare Services for Alzheimers (ROSA) Team:

Michele Aubin, Roxane Borges da Silva, Edeltraut Kroger, Danielle St-Laurent, Valerie Emond, Paul-Emile Bourque, Geoff Anderson, Machelle Wilchesky, Dominique Gagnon, Charo Rodriguez, Linda Lee, Pamela Baxter, Sharon Kaasalainen, Sherry Dupuis, Liette Lapointe, Vladimir Khanassov, Jennifer Ingram, Dallas Seitz, Maude-Émilie Pépin, Maxime Guillette, Nathalie Dame, Frantz Siméon, Noémie Nicol-Clavet, Marine Hardouin, Mary Henein, Lucie Vaillancourt, Mélanie LeBerre, Rebecca Rupp, Muriel Gueriton, Deana Huntsbarger, Sheri Burns, Susan Bronskill, Erin Strumpf, Paula Rochon, Tibor Schuster, and Pam Jarrett

References

- 1. Alzheimer Society of Canada Rising tide: the impact of dementia on Canadian Society. Toronto, ON, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization Dementia: a public health priority, 2012. Available: https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/WHO-Dementia-English.pdf [Accessed 1 Dec 2014].

- 3. Miller BF. A national agenda for research in collaborative care: papers from the collaborative care research network research development conference, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chertkow H. Introduction: the third Canadian consensus conference on the diagnosis and treatment of dementia, 2006. Alzheimers Dement 2007;3:262–5. 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pimlott NJG, Persaud M, Drummond N, et al. . Family physicians and dementia in Canada: Part 1. clinical practice guidelines: awareness, attitudes, and opinions. Can Fam Physician 2009;55:506–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vedel I, Monette M, Lapointe L. Portrait des interventions mises en place Au sein des groupes de famille pour les patients avec des troubles cognitifs liés Au vieillissement (TCV) In: Rapport présenté Au ministère de la Santé et des services sociaux Du Québec, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee L, Hillier LM, Stolee P, et al. . Enhancing dementia care: a primary care-based memory clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:2197–204. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moore A, Patterson C, White J, et al. . Interprofessional and integrated care of the elderly in a family health team. Can Fam Physician 2012;58:e436–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Québec Relever le défi de la maladie d’Alzheimer et des maladies apparentées : une vision centrée sur la personne, l’humanisme et l’excellence. Rapport du comité d’experts en vue de l’élaboration d’un plan d’action pour la maladie d’Alzheimer In: Rapport présidé PAR Le Professeur Howard Bergman, 2009. http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/document-000869/ [Google Scholar]

- 10. Government of Ontario, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Ministry of Education (Early Years and Child Care) . Developing Ontario’s dementia strategy: a discussion paper, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Government of New Brunswick,, Council on Aging . We are all in this together: an aging strategy for new Brunswick, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:29–45. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jull J, Giles A, Graham ID. Community-Based participatory research and integrated knowledge translation: advancing the co-creation of knowledge. Implement Sci 2017;12:150. 10.1186/s13012-017-0696-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bush PL, Pluye P, Loignon C, et al. . Organizational participatory research: a systematic mixed studies review exposing its extra benefits and the key factors associated with them. Implement Sci 2017;12:119. 10.1186/s13012-017-0648-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Canadian Study of Health and Aging Working Group Canadian study of health and aging: study methods and prevalence of dementia. CMAJ 1994;150:899–913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wenger NS, Roth CP, Shekelle P, et al. . Introduction to the assessing care of vulnerable elders-3 quality indicator measurement set. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55 Suppl 2:S247–52. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wenger NS, Solomon DH, Amin A, et al. . Application of assessing care of vulnerable elders-3 quality indicators to patients with advanced dementia and poor prognosis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55 Suppl 2:S457–63. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01375.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Callahan CM, Sachs GA, Lamantia MA, et al. . Redesigning systems of care for older adults with Alzheimer's disease. Health Aff 2014;33:626–32. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vedel I, Sourial N, Arsenault-Lapierre G, et al. . Impact of the Quebec Alzheimer plan on the detection and management of Alzheimer disease and other neurocognitive disorders in primary health care: a retrospective study. CMAJ Open 2019;7:E391–8. 10.9778/cmajo.20190053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schneeweiss S, Seeger JD, Maclure M, et al. . Performance of comorbidity scores to control for confounding in epidemiologic studies using claims data. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:854–64. 10.1093/aje/154.9.854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Qualis Health, Safety Net Medical Home Initiative The patient-centered medical home assessment version 4.0. Seattle, WA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gauthier S, Patterson C, Chertkow H, et al. . Recommendations of the 4th Canadian consensus conference on the diagnosis and treatment of dementia (CCCDTD4). Can Geriatr J 2012;15:120–6. 10.5770/cgj.15.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Henein M, Arsenault-Lapierre G, Godard-Sebillotte C, et al. . Organizational best practices for dementia questionnaire: development and validation. McGill Family Medicine Studies Online 2020;15. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Levesque J-F, Pineault R, Provost S, et al. . Assessing the evolution of primary healthcare organizations and their performance (2005-2010) in two regions of Québec Province: Montréal and Montérégie. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:95. 10.1186/1471-2296-11-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE. Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care 1989;27:S110–27. 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arsenault-Lapierre G, Sourial N, Hardouin M, et al. . Validation of a questionnaire for family physicians: knowledge, attitude, practice on dementia care. Canadian Journal of Aging 2021;40 10.1017/S0714980820000069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arsenault-Lapierre G, Sourial N, Vedel I, et al. . Measuring knowledge, practice, and attitudes toward dementia in nurses and other allied health professionals’: Questionnaire development and validation. McGill Family Medicine Studies Online 2020;15:e02 10.1093/geroni/igx004.3480 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23:334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3 edn Sage Publications, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The SAGE Handbook of qualitative research. Sage, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Caracelli VJ, Greene JC. Data analysis strategies for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educ Eval Policy Anal 1993;15:195–207. 10.3102/01623737015002195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, et al. . Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci 2012;7:50. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Government of Canada, Ministry of Health National strategy for alzheimer’s disease and other dementias act, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Canadian Academy of Health Sciences CAHS panel for the assessment of evidence and best practices for the development of a Canadian dementia strategy, 2018. http://www.cahs-acss.ca/latest-assessments-in-progress/? [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-035916supp001.pdf (52.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035916supp002.pdf (139.5KB, pdf)