Abstract

Costal cartilage grafting is a commonly used reconstruction procedure, particularly in rhinoplasty. Although costal cartilage is broadly used in reconstructive surgery, there are differing opinions regarding which costal cartilage levels provide the most ideal grafts. Grafts are typically designed to match the shape of the recipient site. The shapes of costal cartilage grafts have been described as “boat-shaped,” “C-shaped,” “canoe-shaped,” “U-shaped,” “crescent-shaped,” “L-shaped,” “semilunar,” “straight,” and “Y-shaped.” The shapes of costal cartilages are thought to lend themselves to the shapes of certain grafts; however, there has been little study of the shapes of costal cartilages, and most reports have been anecdotal. Therefore, this study is aimed to detail the average shapes of the most commonly grafted cartilages (i.e., the fifth to seventh cartilages). A total of 96 cadaveric costal cartilages were analyzed through geometric morphometric analysis. The fifth costal cartilage was determined to have the straightest shape and would therefore be particularly suitable for nasal dorsum onlay grafting. The lateral portions of the sixth and, particularly, the seventh costal cartilages have the most acute curvature. Therefore, they would lend themselves to the construction of an en bloc “L”-shaped or hockey stick-shaped nasal dorsum-columellar strut graft.

Keywords: rhinoplasty, cartilage grafting, cartilage harvest, facial reconstruction, nasal reconstruction

Costal cartilage (CC) has increasingly become the material of choice for rhinoplasty in patients who require dorsal augmentation and nasal tip projection. The advantages of CC grafting include relative ease of carving, abundant volume, and its inherent capacity to survive in a surrounding tissue bed without the need for a specific blood supply.1

There is debate about the optimal cartilage level from which to obtain grafts.2–7 Moreover, there is further contention as to which side of the rib cage is best to harvest the cartilage. Some surgeons prefer harvesting from the right side because it is more convenient for the right-handed surgeon while others prefer a left-sided harvest to facilitate a two-team approach.4,5,8

The native shapes of particular CCs influence the suitability for particular types of grafts. For example, Gibson and Davis9 noted that the shape of the costal margin cartilages are “peculiarly suitable” for nasal bridge grafts. The slender and curved eighth CC may be ideal for an alar batten graft, but not for dorsal augmentation.10 Harvesting CC from regions of the rib cage that resemble the desired graft shape enables the surgeon to minimize carving and to achieve a balanced cross-section more closely. Most importantly, carving a balanced cross-section is crucial to reduce postoperative warping—a potential pitfall to cartilage grafting.9,10

Despite the importance of CC grafting in reconstructive surgery, little agreement exists with regard to both the optimal CC rib level and the harvesting side for grafting. Decisions regarding both the cartilage level and side from which to harvest the graft may depend on the inherent shape of the CC as well as the ultimate shape of the desired graft. Unfortunately, few studies have analyzed the shape of CC. Because shape may influence the selection of optimal CC grafts, the assessment of cartilage shape is warranted. Therefore, the aim of this study is to determine the average shapes and most likely shape variations of the most commonly grafted CCs (i.e., the fifth to seventh CCs) from both the left and right side of the rib cage.

Materials and Methods

The study assessed the CCs of cadavers with the permission of the West Virginia Anatomical Board. A total of 16 cadavers ranging in age from 35 to 99 years, were dissected with the intent of exposing the fifth to seventh CCs along with the sternum and the ribs (►Fig. 1). There was no evidence of gross pathology or confounding anatomical variation (e.g., bifid rib) in the cadaveric population.11 To adequately visualize the superior and inferior margins of the CCs, soft tissues were removed from the interchondral spaces. A total of 96 CCs were included in the study (32 from each of the fifth, sixth, and seventh rib levels).

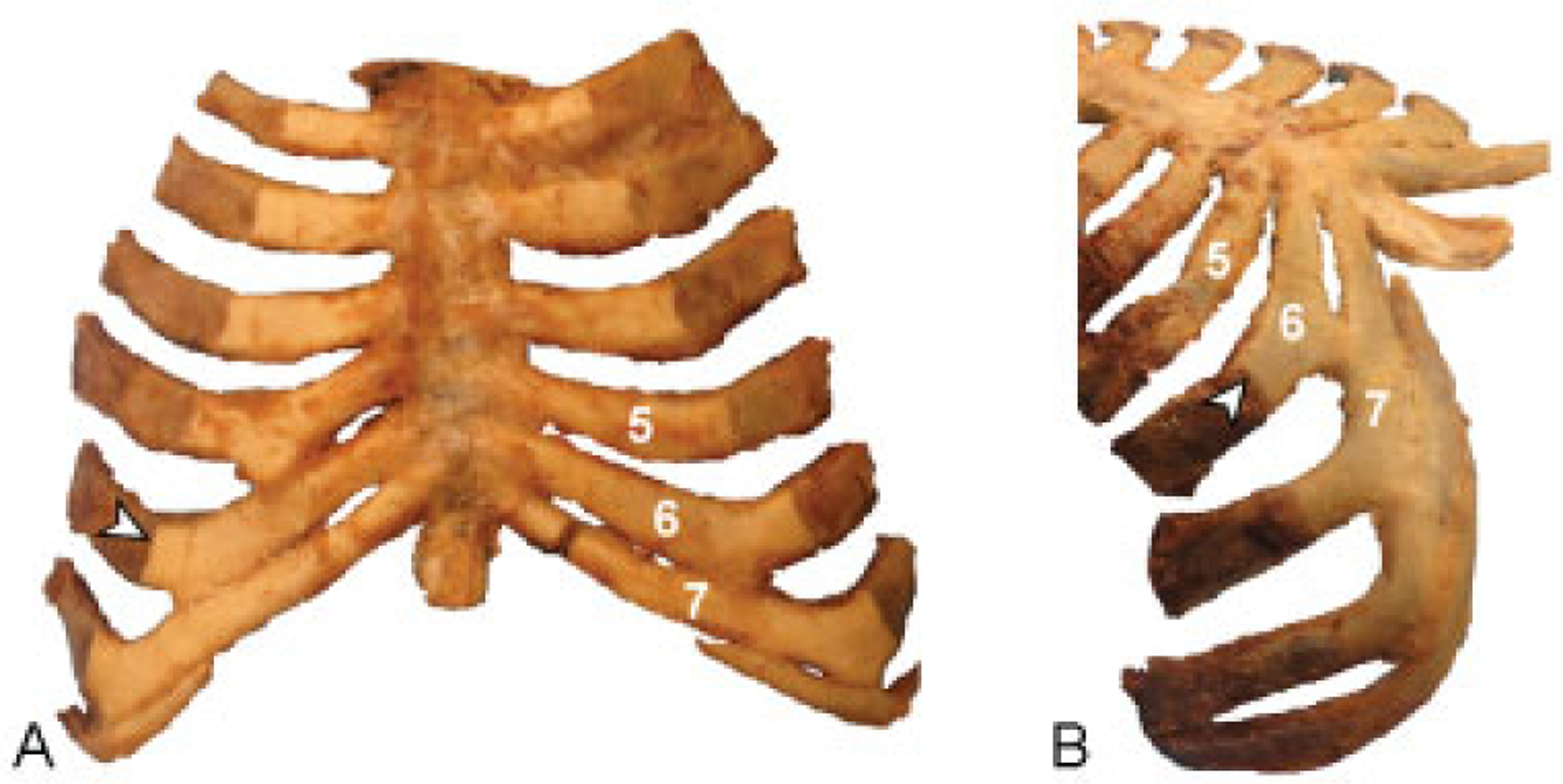

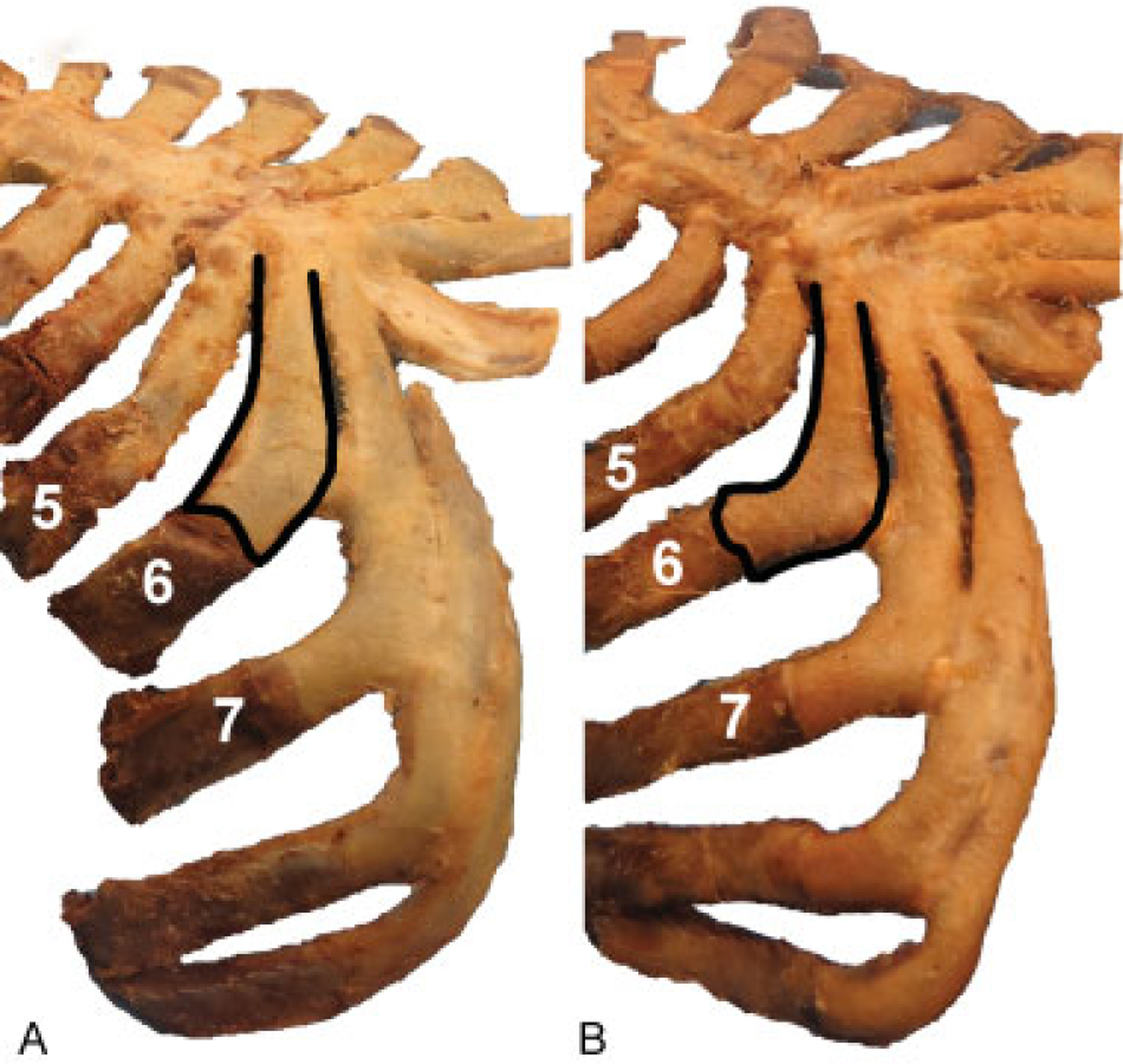

Fig. 1.

Anterior (A) and inferolateral (B) views of the costal cartilages. Arrowheads mark the interface between the rib and the costal cartilage. The junction between the rib and the costal cartilage was well-defined by the contrast in color between rib and cartilage tissue. Costal cartilages 5, 6, and 7, common harvesting sites for cartilage grafting, have been labeled accordingly.

Photography of the CCs was performed with a digital camera (Canon PowerShot SX50 HS; Canon U.S.A., Inc.). Photographs were taken of the fifth to seventh CCs from the anterior as well as from the inferolateral views to visualize the cartilage en face (►Fig. 1). The junction between the superomedial CC and the sternum was selected as the location from which to begin manually outlining the perimeter of the cartilage in TPSdig2 software (version2.22).12 The points along the manually drawn curve were then resampled with TPSdig2 to have a total of 100 equidistant points, labeled sequentially from point 1 (superomedial CC) to point 100 (inferomedial CC). In the event that the CC formed bridges with adjacent cartilages, the bridging cartilage was intentionally ignored to assess the consistent anatomy.13

The coordinates of these 100 landmarks were generated for all of the 96 cartilages, yielding a total of 9,600 two-dimensional landmarks. Consensus shapes amidst clouds of the landmark data points were generated from a Procrustes superimposition aligned by principal axes with the Geomorph package for R software.14 Principal components analysis was performed with MorphoJ software.15 Bilateral symmetry of cartilages was assessed by discriminant function analysis with MorphoJ.15 Because the seventh cartilage was observed to have a curvature which oftentimes deviated out of the coronal plane, additional photographs were taken of the seventh CC from the superior view to assess the curvature in the axial plane (►Fig. 2).

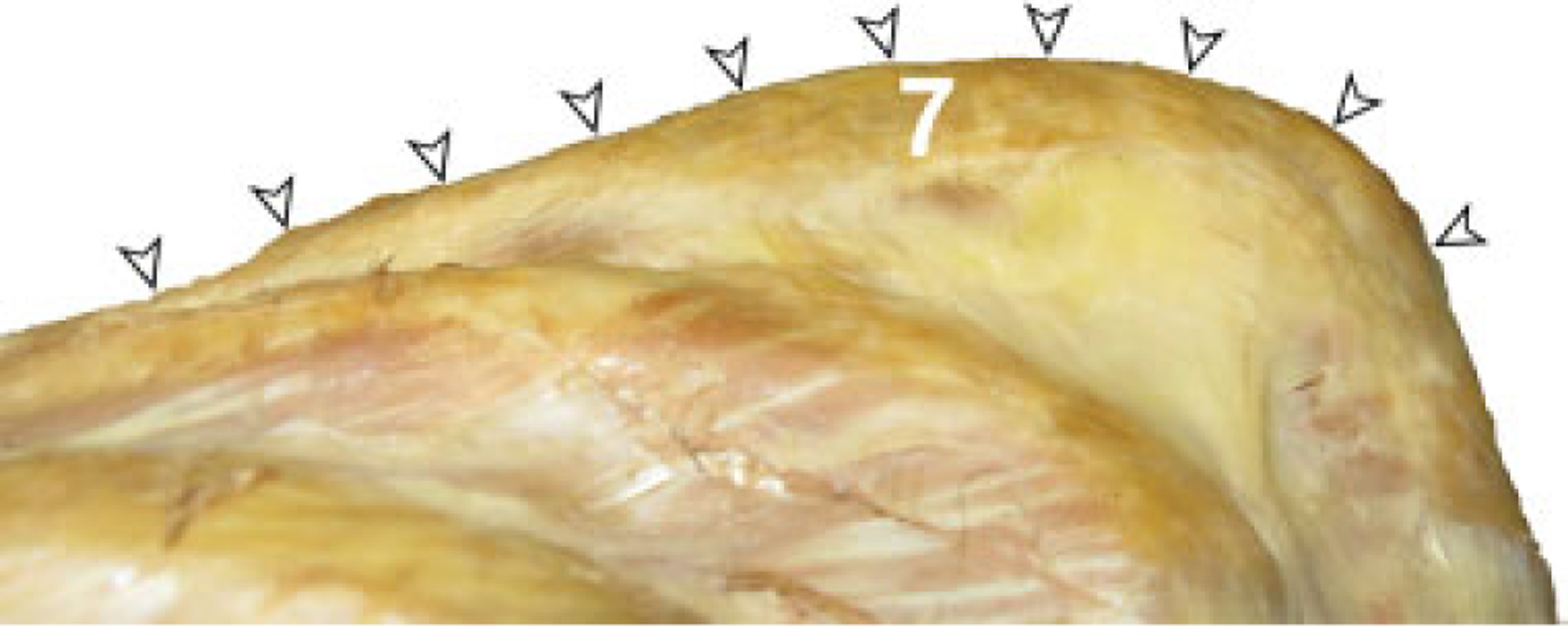

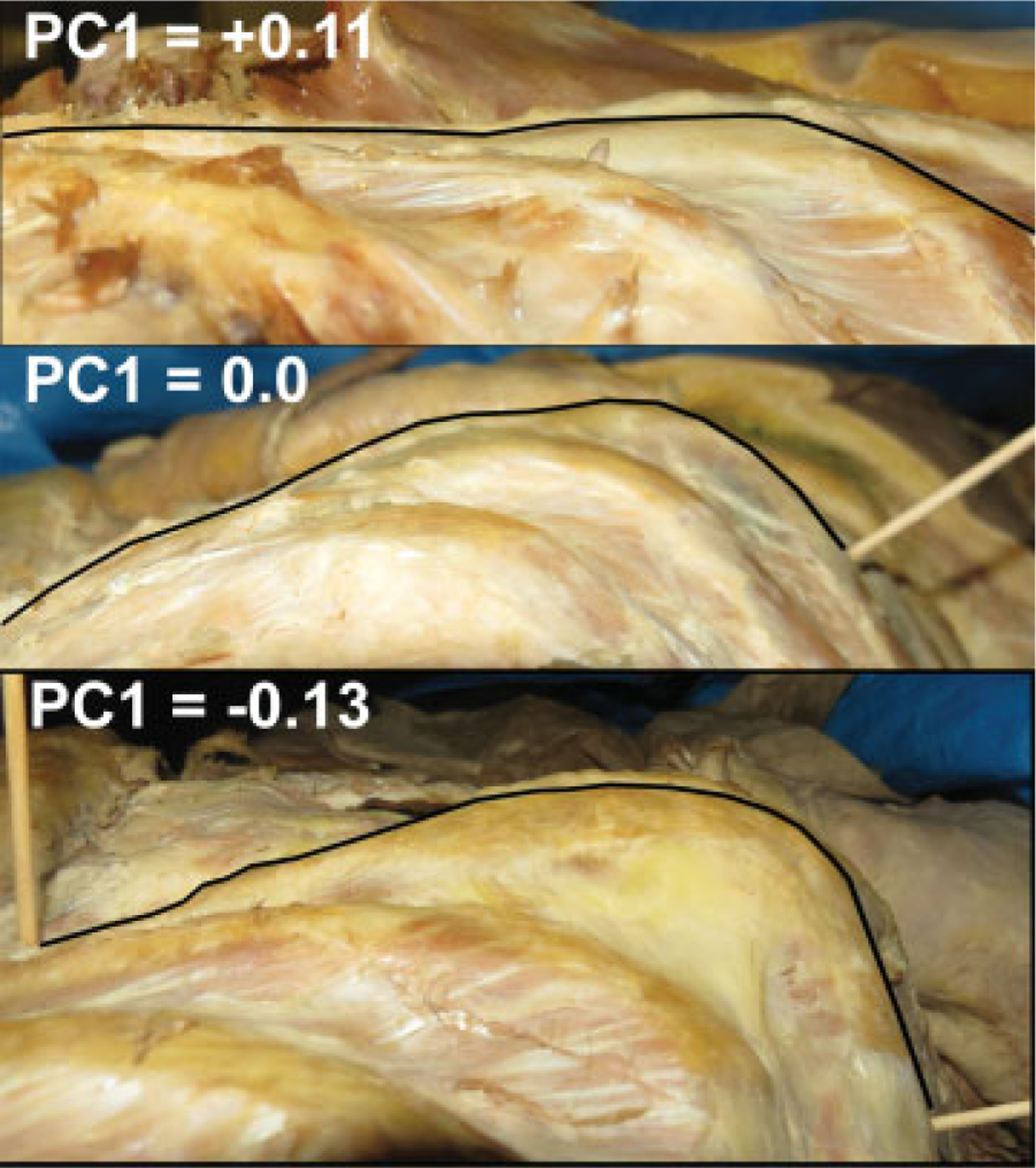

Fig. 2.

Superior view of the anterior bowing of the seventh costal cartilage occurring in the axial plane. Arrowheads designate the anterior margin of the seventh costal cartilage.

Results

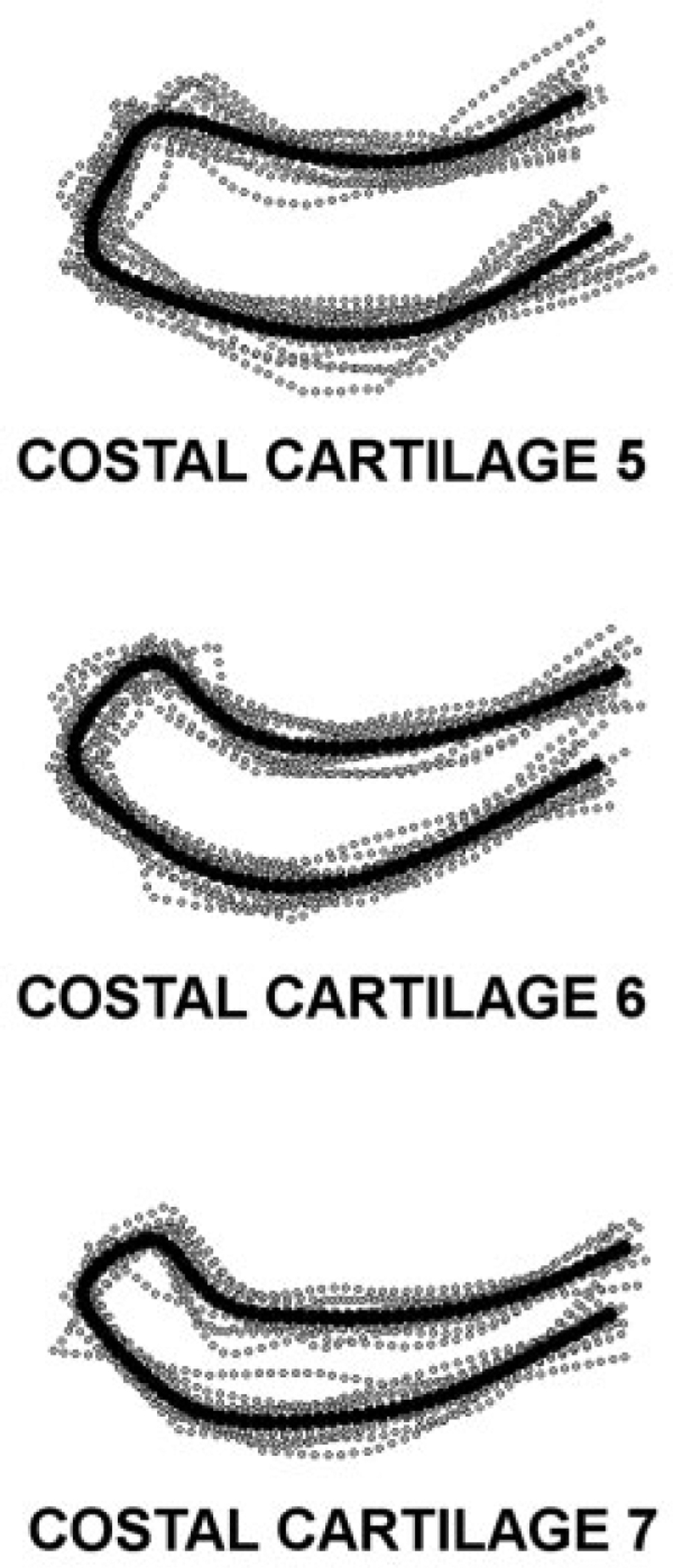

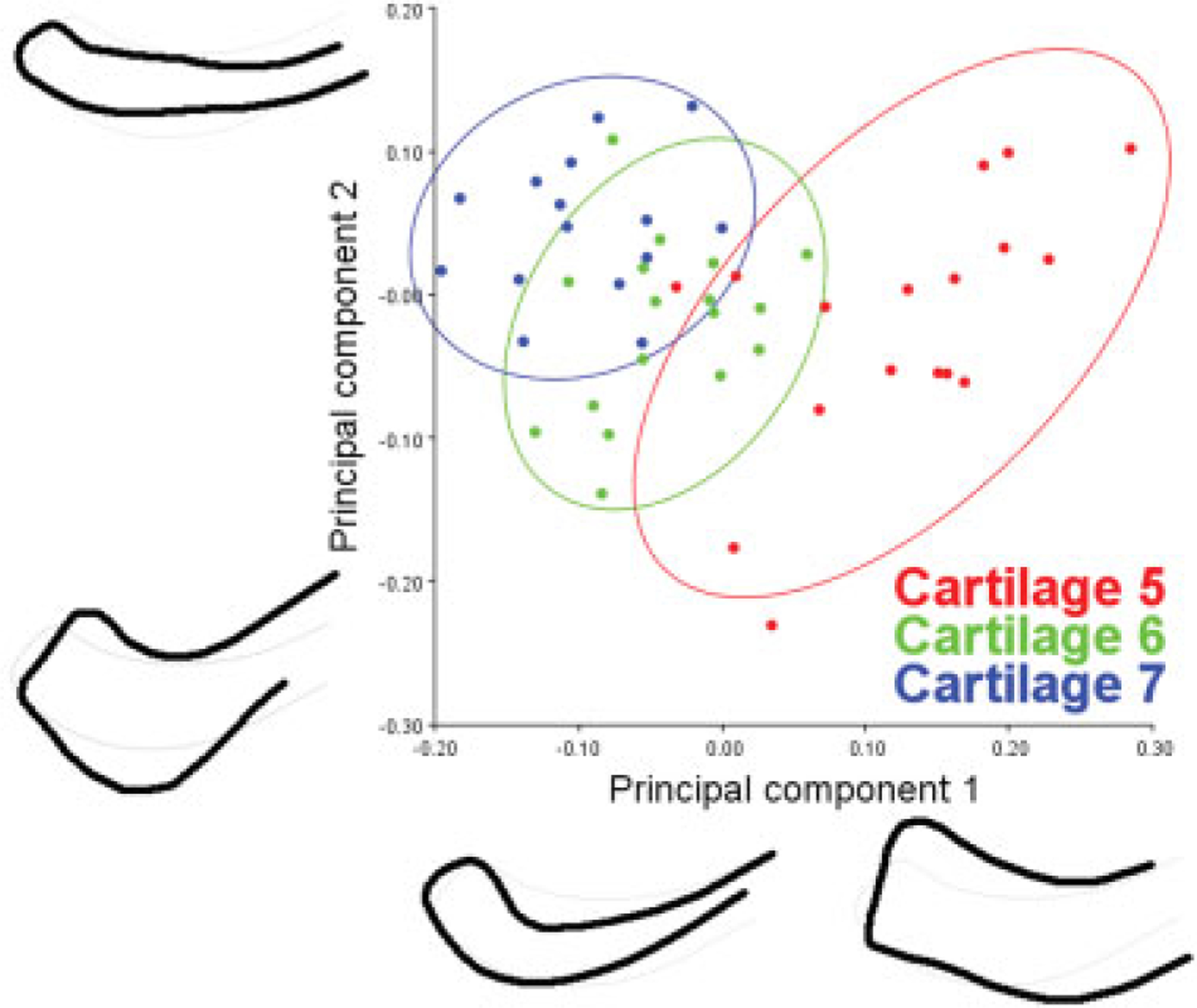

Consensus shapes for the fifth to seventh CCs can be found in ►Fig. 3. Discriminant function analysis revealed symmetry between left- and right-sided CCs from each cartilage level. Principal component analysis revealed trends in the shape of cartilage at each cartilage level (►Fig. 4). The first two principal components accounted for 76.47% of the total shape variation (PC1 = 54.18%; PC2 = 22.29%) (►Fig. 4). The results of the principal components analysis revealed a gradual shape change from the fifth CC to the seventh CC. The CC shape changed from relatively broad and straight at the fifth CC to relatively narrow and acutely curved at the seventh CC. The 90% confidence ellipses surrounding the fifth and seventh CCs overlapped with that of the sixth CCs highlighting this transition zone in shapefrom straight to L shape. However, there was almost no overlap between the confidence ellipses of the fifth and seventh CCs (►Fig. 4). Also, the widest variety of shape variation occurs among the fifth cartilages and the least amount of shape variation occurs among the seventh cartilages, which tend to have a consistently slender shape and L-shaped curvature (►Fig. 3). The variation in shape of the seventh CC was most pronounced over the lateral aspect with anterior to posterior bowing (►Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Consensus shapes of the fifth to seventh costal cartilages (black curves), determined by procrustes superimposition of outline curves taken from the inferolateral en face photographs of the cartilage (corresponding to ►Fig. 1B), amidst coordinate point clouds formed from 100 data landmarks (gray dots) along costal cartilages. The consensus shapes comes from a sample of cadavers with known diversity of race, age, as well as sex and also having no apparent cartilaginous pathology. Discriminant function analysis revealed bilateral symmetry at each cartilage level.

Fig. 4.

Principal components analysis demonstrating the variation in the shapes of the fifth to seventh costal cartilages as viewed en face from the inferolateral angle. Specimens from each cartilage level are encompassed by 90% confidence ellipses. The first two principal components account for 76.47% of shape variation among the cartilages. The first principal component explains 54.18% of total cartilage shape variation and the second principal component explains 22.29% of shape variance. The widest range of shape variation occurred at the fifth costal cartilage. Conversely, the seventh costal cartilage shapes clustered tightly into a group of elongated and acutely curved cartilages. The shapes of the costal cartilages tend to become relatively longer, narrower, and more curved as they transition from the fifth cartilage to the seventh cartilage.

Fig. 5.

Gross cadaveric images demonstrating the variation of the anterior–posterior curvature of the seventh costal cartilage as viewed from the superior. Results of a principal components analysis revealed that the first principal component explains 84.76% of shape variation of the anterior contour of the seventh costal cartilage. The image demonstrates the average curvature (PC1 = 0.0) and the extremes of curvature along the positive and negative PC1 axis. The anterior contour of the seventh costal cartilage ranges from nearly flat to having a pronounced anterior convexity. However, the average contour of the anterior aspect of the seventh rib is gently convex. The curvature was most pronounced at the general location of approximately two-third the length of the cartilage away from the lateral sternal line (i.e., one-third the length of the cartilage from the rib–cartilage interface).

Discussion

Successful aesthetic outcomes are a high priority after rhinoplasty and careful selection of cartilage is critical. CC predictably varies in size; however, the study of CC shape has been largely overlooked. This study is the first to report shape variation among the most commonly harvested CCs.

In general, surgeons prefer the graft for a dorsal onlay to be from a relatively straight piece of cartilage with a balanced cross-section, a flat ventral surface, and a gently curved dorsal surface.10 The results of this geometric morphometric study identify the CC with the most consistently straight contour along its entire margin to be that of the fifth CC (►Figs. 3 and 4). Although the medial four-fifths of the sixth or seventh rib may provide sufficient length as an alternative to the fifth CC (►Fig. 6), some caution should be exercised as this study identifies sometimes pronounced cartilage curvature of the sixth and seventh costal cartilages beginning at the lateral one-third of the CC (►Fig. 5).

Fig. 6.

View of two different rib cages from the inferolateral angle that demonstrate variation in the shape of the costal cartilages. (A) The sixth costal cartilage, highlighted with a black outline, is relatively straight when compared with that of the sixth costal cartilage in (B), which is relatively curved. The cartilage in (B) would be more suitable for a combined dorsal-columellar strut graft than that of (A). Moreover, the seventh cartilages in both A and B are naturally L-shaped, therefore lending themselves to an en bloc dorsum-columellar strut graft. As demonstrated in ►Fig. 4, the seventh costal cartilage tends to have the most consistent L-shape when compared with cartilages 5 and 6.

A dorsal onlay graft may be optimally carved from a straight piece of cartilage utilizing the principle of balanced cross-sections.9 If the rib is curved, it is not possible to carve a completely balanced cross-section as one will inevitably infringe upon the periphery and therefore increase the degree of possible warpage.10 Although the fifth rib has the most varied shape, it also tends to be the flattest and straightest (►Figs. 3 and 4). The average fifth rib is therefore ideal for a dorsal onlay graft.

Augmentation of the nasal dorsum and improving nasal tip projection often requires a significant volume of cartilage. Reconstruction with dorsal and columellar struts is often achieved with two separate pieces of straight cartilage. As an alternative, the dorsal strut and columellar strut could be constructed from a single L-shaped unit.9,16 To reconstruct the dorsum and columella with a single L-shaped graft the sixth and seventh CCs should be considered. It is important to note that the sixth cartilage tends to have less pronounced in-plane curvature than that of the seventh cartilage. However, some sixth cartilages do have an inherent “L” shape (►Fig. 6).

The seventh rib possesses the most consistent natural “L” shape as viewed from the anterior angle and is ideal for an “L-” shaped graft (►Figs. 1 and 2). Of note, this study identifies variable bowing and convexity of the seventh rib (►Fig. 5). The most extreme example of anterior bowing (►Fig. 2) was noted in a cadaver with a “barrel chest” with underlying pulmonary disease. This type of anterior bowing is uncommon in non-geriatric patients and would be unusual in a rhinoplasty candidate. Nonetheless, the surgeon should be aware of the possibility of anterior bowing and have contingency plans.

The fifth CC is relatively broad with respect to the sixth and seventh ribs which are increasingly slender and “J” or “L” shaped (►Figs. 1–3). The gentle in-plane curvature of the sixth and seventh CC may lend itself to reconstruction of the lower lateral crus of the alar cartilage or intercartilaginous grafting to treat external valve collapse in which the ideal graft is isolated from a single curved cartilage.17

Conclusion

Successful aesthetic outcomes in rhinoplasty depend on careful selection of CC. The ideal CC has adequate volume while simultaneously possessing geometry that already lends itself to the desired shape. This report objectively demonstrates that each CC level has a unique shape. A comprehensive knowledge of the shape of the CC will enable the surgeon to carve CC efficiently while maintaining a balanced cross-section which will minimize warpage and ensure a long-lasting aesthetic result.

References

- 1.Goode RL. Bone and cartilage grafts: current concepts. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1972;5(03):447–455 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrbohm H, Tardy ME Jr. Funktionell-ästhetische Chirurgie der Nase: Septorhinoplastik. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme-Verlag; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheen JH, Sheen AP. Aesthetic Rhinoplasty. 2nd ed Vol. 1 St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toriumi DM, Swartout B. Asian rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 2007;15(03):293–307, v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marin VP, Landecker A, Gunter JP. Harvesting rib cartilage grafts for secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;121(04): 1442–1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Defatta RJ, Williams EF III. The decision process in choosing costal cartilage for use in revision rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg 2008; 24(03):365–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniel RK. Rhinoplasty: An Atlas of Surgical Techniques. New York, NY: Springer; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cochran CS, Gunter JP. Secondary rhinoplasty and the use of autogenous rib cartilage grafts. Clin Plast Surg 2010;37(02): 371–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson T, Davis WB. The distortion of autogenous cartilage grafts: its cause and prevention. Br J Plast Surg 1958;10:257–274 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim DW, Shah AR, Toriumi DM. Concentric and eccentric carved costal cartilage: a comparison of warping. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2006;8(01):42–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wattanasirichaigoon D, Prasad C, Schneider G, Evans JA, Korf BR. Rib defects in patterns of multiple malformations: a retrospective review and phenotypic analysis of 47 cases. Am J Med Genet A 2003;122A(01):63–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohlf FJ. TpsDig, version 2.22, 2015. Available at http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/. Accessed Month DD, YYYY

- 13.Briscoe C The interchondral joints of the human thorax. J Anat 1925;59(Pt 4):432–437 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams DC, Otárola-Castillo E. Geomorph: an R package for the collection and analysis of geometric morphometric shape data. Methods Ecol Evol 2013;4:393–399 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klingenberg CP. MorphoJ: an integrated software package for geometric morphometrics. Mol Ecol Resour 2011;11(02):353–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopes DD, Andrade BGA, Vaena MLHT, Mota DWC. Single block costal cartilage graft in rhinoplasty. Rev Bras Cir Plást 2011; 26:453–460 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal KS, Bachhav M, Shrotriya R. Namaste (counterbalancing) technique: Overcoming warping in costal cartilage. Indian J Plast Surg 2015;48(02):123–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]