Abstract

Objectives: Bipolar disorder (BD) is a debilitating illness that often starts at an early age. Prevention of first and subsequent mood episodes, which are usually preceded by a period characterized by subthreshold symptoms is important. We compared demographic and clinical characteristics including severity and duration of subsyndromal symptoms across adolescents with three different bipolar-spectrum disorders.

Methods: Syndromal and subsyndromal psychopathology were assessed in adolescent inpatients (age = 12–18 years) with a clinical mood disorder diagnosis. Assessments included the validated Bipolar Prodrome Symptom Interview and Scale—Prospective (BPSS-P). We compared phenomenology across patients with a research consensus conference-confirmed DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition) diagnoses of BD-I, BD—not otherwise specified (NOS), or mood disorder (MD) NOS.

Results: Seventy-six adolescents (age = 15.6 ± 1.4 years, females = 59.2%) were included (BD-I = 24; BD-NOS = 29; MD-NOS = 23) in this study. Median baseline global assessment of functioning scale score was 21 (interquartile range = 17–40; between-group p = 0.31). Comorbidity was frequent, and similar across groups, including disruptive behavior disorders (55.5%, p = 0.27), anxiety disorders (40.8%, p = 0.98), and personality disorder traits (25.0%, p = 0.21). Mania symptoms (most frequent: irritability = 93.4%, p = 0.82) and depressive symptoms (most frequent: depressed mood = 81.6%, p = 0.14) were common in all three BD-spectrum groups. Manic and depressive symptoms were more severe in both BD-I and BD-NOS versus MD-NOS (p < 0.0001). Median duration of subthreshold manic symptoms was shorter in MD-NOS versus BD-NOS (11.7 vs. 20.4 weeks, p = 0.002) and substantial in both groups. The most used psychotropics upon discharge were antipsychotics (65.8%; BD-I = 79.2%; BD-NOS = 62.1%; MD-NOS = 56.5%, p = 0.227), followed by mood stabilizers (43.4%; BD-I = 66.7%; BD-NOS = 31.0%; MD-NOS = 34.8%, p = 0.02) and antidepressants (19.7%; BD-I = 20.8%; BD-NOS = 10.3%; MD-NOS = 30.4%).

Conclusions: Youth with BD-I, BD-NOS, and MD-NOS experience considerable symptomatology and are functionally impaired, with few differences observed in psychiatric comorbidity and clinical severity. Moreover, youth with BD-NOS and MD-NOS undergo a period with subthreshold manic symptoms, enabling identification and, possibly, preventive intervention of those at risk for developing BD or other affective episodes requiring hospitalization.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, risk, prevention, subsyndromal, adolescence

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a chronic, recurrent, and often debilitating illness (Skjelstad et al. 2010) characterized by fluctuations in mood, energy, cognition, and behavior (Grande et al. 2016). BD is associated with significant impairments in everyday functioning (Bowie et al. 2010), and is ranked as the illness with the second greatest effect on days out of role functioning (Alonso et al. 2011). However, delay between illness onset and diagnosis has been reported to be as long as 5–10 years (Berk et al. 2007).

Clinical presentation and diagnosis of pediatric BD has been controversial (Moreno et al. 2007; Luby and Navsaria 2010; Van Meter et al. 2016a), especially the decrease in the threshold for diagnosing BD and the concept of the bipolar spectrum (Grande et al. 2016). Nevertheless, 60%–65% of people with BD experience their first symptoms before adulthood (Perlis et al. 2004), and agreement is substantial that the illness trajectory of early-onset BD is more severe than adult-onset BD (Bowie et al. 2010; Arango et al. 2014; Parellada et al. 2017) and is associated with significant impairment (Hunt et al. 2016), and a chronic course and significant treatment resistance (Luby et al. 2010). In addition, childhood onset of bipolar-like symptoms are a good predictor for the development of full BD (Carlson and Pataki 2016; Hafeman et al. 2016).

The longitudinal course of children and adolescents with BD is often manifested by changes in symptom polarity with a fluctuating course, showing a dimensional continuum of bipolar symptom severity from subsyndromal symptoms to mood syndromes meeting full Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria (Birmaher et al. 2006). Nevertheless, bipolar-spectrum pathologies below the level of BD-I (Correll et al. 2007, 2014), and antecedent conditions (Faedda et al. 2014, 2015) also have a significant impact on functionality and quality of life (Luby et al. 2010; Carlson et al. 2016).

BD-I is characterized by the occurrence of at least one manic episode, usually in association with one or more depressive episodes (American Psychiatric Association 2013). As per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), one episode of mania without depression is sufficient for a diagnosis of BD-I, as long as there is no other cause that better explains the symptoms (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

BD—not otherwise specified (BD-NOS), renamed “unspecified BD” in the fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association 2013) is characterized by the presence of symptoms that lack sufficient duration or severity for a BD-I or II diagnosis. This subgroup was defined in the COBY study (Birmaher et al. 2006) and included distinct periods of abnormally elevated or irritable mood with either one less B criterion symptom, or presence of all symptoms, but lasting at least ≥4 hours on ≥4 cumulative instead of ≥4 consecutive days.

Patients with mood disorder NOS (MD-NOS) named “other specified BD” in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013), have characteristic symptoms of BD and related disorders that do not meet full criteria for any category previously mentioned and is characterized by subthreshold periods of mania or hypomania that, unlike BD-NOS, last <4 hours per day for <4 cumulative days.

Early signs and symptoms have been detected in BD, including some subthreshold symptoms, which have been reported to precede the initial mood episode in BD and the recurrent mood episodes (Hauser and Correll 2013; Van Meter et al. 2016b). Many of these characteristics have been identified too in youth at genetic risk for BD (Lombardo et al. 2012; Birmaher et al. 2013; Hafeman et al. 2016), including disturbances in mood, cognition, and behavior (Duffy et al. 2007, 2010; Egeland et al. 2012; Mesman et al. 2013, 2016, 2017; McIntyre and Correll 2014; Hafeman et al. 2016). These presentations include nonspecific psychiatric symptoms, like anxiety or irritability (Compton et al. 2010), among other more specific affective symptoms, such as decreased need for sleep or racing thoughts (Correll et al. 2014). These latter “hallmark” symptoms could be more specific to BD and are relatively ubiquitous among youth who meet full BD criteria (Van Meter et al., 2016a).

A symptomatic prodrome before the first hypomanic/manic and/or depressive episode in BD has been described (Noto et al. 2015), lasting over 2 years, and a shorter period characterized by subthreshold symptoms that appear before full-blown recurrent episodes (Van Meter et al. 2016a). This has led to increased awareness that recognition and longitudinal assessment of subthreshold symptoms in at-risk populations (either for a first affective episode or for a recurrent mood episode) is important for understanding the illness course (Carlson et al. 2016). Although several risk factors for BD have been identified, including circadian rhythm abnormalities (Lenox et al. 2002), temperamental characteristics (Akiskal et al. 2005; Mendlowicz et al. 2005), neurocognitive deficits (Krabbendam et al. 2005), and adverse life events (Janiri et al. 2015; Pan et al. 2017), specific characteristics and endophenotypes that reliably allow early recognition of BD, remain undiscovered.

Identifying subthreshold symptoms in at-risk individuals might lead to new interventions that could prevent the onset of new affective episodes. Although there is currently little evidence for interventions at these stages (Rios et al. 2015), recent attempts to intervene earlier have led to some positive outcomes (Pfennig et al. 2014; Hunt et al. 2016). For instance, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT) (Goldstein et al. 2018) and family-focused therapy (Miklowitz et al. 2013) have shown promising results.

Rating scales and checklists, which would facilitate the development and identification of early symptoms show great promise (Hunt et al. 2016). Thus, newly developed tools, such as the Bipolar Prodrome Symptom Interview and Scale—Prospective (BPSS-P) (Correll et al. 2014), are relevant.

Unfortunately, subthreshold symptoms are often not correctly identified and addressed, limiting the initiation of preventive interventions. Previous studies have reported and compared different affective symptoms that appear in BD-spectrum disorders (Tijssen et al. 2010; Hafeman et al. 2013, 2016, 2017; Van Meter et al. 2016b; Connor et al. 2017) or have retrospectively characterized the phase preceding the emergence of an episode of mania (Conus et al. 2010; Correll et al. 2014). However, to our knowledge, no study to date has compared these particular BD-spectrum diagnoses with each other regarding mania-like mood states, using a validated instrument, such as the BPSS-P, and included diagnoses that may be precursor stages for manifest BD, such as BD-NOS and MD-NOS.

Thus, the aim of this study was to characterize and compare patients with different BD-spectrum disorders regarding their clinical characteristics and illness course before hospitalization, including subthreshold symptoms that could lead to a more severe affective episode in the future.

We hypothesized that adolescents with BD-I, BD-NOS, and MD-NOS would report clinical impairment, as defined by low functioning and severe and clinically relevant psychopathology, and relevant threshold and subthreshold symptoms of mania and depression, which would be beyond what could be expected owing to the characteristics of each diagnostic category by their definition (see definitions provided in this section), and which would be most severe and florid in patients with BD-I, followed by those with BD-NOS, and finally, by MD-NOS.

Methods

Setting

Participants were recruited between September 2009 and July 2017 from the adolescent inpatient unit of The Zucker Hillside Hospital, from the ongoing Adolescent Mood and Psychosis Study (AMDPS) (Lo Cascio et al. 2016), an observational study aiming to prospectively characterize the BD prodrome.

This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01383915).

Participants

Inclusion criteria for AMDPS were as follows: (1) age: 12–18 years; (2) research diagnosis, using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders (First et al. 1996), supplemented by pediatric diagnoses from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime version (Kaufman et al. 1997) of either (a) BD-1, (b) BD-NOS (renamed “unspecified BD” DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association 2013), defined by the COBY study criteria (Birmaher et al. 2006), that is, distinct periods of abnormally elevated or irritable mood with either one less B mania criterion symptom, or presence of all required symptoms for a BD-I or BD-II diagnosis, but lasting at least ≥4 hours on ≥4 cumulative instead of ≥4 consecutive days, or (c) MD-NOS (named “other specified BD” in the DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association 2013), defined by presence of symptoms of BD and related disorders that do not meet full criteria for any syndromal mood disorder and that is characterized by subthreshold periods of mania or hypomania that, unlike BD-NOS, last <4 hours per day for <4 cumulative days; (3) currently admitted into a psychiatric hospital; (4) subject and parent (if subject <18 years) willing and able to provide written, informed consent/assent.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) an estimated premorbid IQ <70; (2) fulfilling DSM-IV criteria for pervasive developmental disorder or autism spectrum disorders; and (3) a history of any medical condition known to affect the brain. For the purpose of this study, patients with a DSM-IV diagnosis of BD-I, BD-NOS, or MD-NOS using the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children—Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL) (Birmaher et al. 2009) and the BPSS-P (Correll et al. 2014) were selected from the overall AMDPS study sample. Psychiatric diagnoses were established according to DSM-IV criteria through research consensus conference (led by CUC) based on the KSADS and BPSS-P in-person interview assessments of the adolescent and the caregiver. Information from the parent and youth interviews was integrated for the diagnostic and psychopathology. When there was a discrepancy, the more severe of the two ratings was accepted, assuming that symptoms are more likely forgotten or hidden than invented or exaggerated.

Written informed consent for this Northwell Health Institutional Review Board-approved study was obtained from all subject's guardians or legal representatives of minors and written assent was obtained from each adolescent subject, unless they were 18 and provided written informed consent.

Clinical and functional assessments

The BPSS-P (Correll et al. 2014) was administered to adolescent inpatients with a clinical diagnosis of affective or psychosis-spectrum disorder. This tool was developed to characterize prodromal and subsyndromal bipolar mania and depression states and to assess the evolution of BD at any stage. The BPSS-P was developed based on an extension downward of DSM criteria for BD and major depressive disorder, and available rating scales for major depressive disorder and BD, a review of the existing literature regarding risk factors and early symptoms and signs of BD, published scales and interviews for the assessment of the psychotic prodrome, input from experts in the area of the schizophrenia prodrome and BD, and open questioning of youth with BD and their caregivers. The BPSS-P is comprised of a 10-item Mania Symptom Index, a 12-item Depression Symptom Index, and a 6-item General Symptom Index.

The BPSS-P was designed to characterize and evaluate the lifetime presence and severity of prodromal/subsyndromal and syndromal manic, depressive, and general symptoms. Symptom severity was rated on an ordinal scale with 0 = absent, 1 = questionably present, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = moderately severe, 5 = severe, 6 = extreme, with a rating of “moderate” being the lowest subsyndromal rating [rating = 3, i.e., symptoms are “beginning to be noticed by others” and are not just “fully explained by external factors” that would be a rating = 2, but not yet “beginning to interfere with functioning” (rating = 4)]. In addition, the frequency of these symptom episodes is recorded on a Likert scale, as follows: 0 = none, 1 = < once/month, 2 = once/month, 3 = 2–3 times/month, 4 = 4–7 times/month, 5 = 8–27 times/month, 6 = ≥ 28 times/month. Furthermore, duration, onset, and pattern of these symptoms are also recorded.

The BPSS-P has good to excellent psychometric properties including very high internal consistency, inter-rater reliability, and convergent validity (Correll et al. 2014). For the purpose of this study, we analyzed severity as a categorical variable [i.e., presence of symptoms rated at moderate severity (rating = 3) or higher]. For the duration of subthreshold symptoms rated at moderate or higher severity, we restricted the analyses to those individuals who by definition had not (yet) experienced an episode of that polarity, that is, subthreshold symptoms of mania and general symptoms in the BD-NOS and MD-NOS groups and subthreshold symptoms of depression in the MD-NOS group.

Additional rating scales were administered to both adolescents and their caregivers, including the Clinical Global Impression—Severity scale (CGI-S; range = 1–7), which assesses the overall severity of illness (Guy 1976), the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF; range = 0–100) (Piersma and Boes 1997), which assesses functionality, and The Montgomery-Ǻsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; range = 0–60) (Montgomery and Asberg 1979) and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS; range = 0–60) (Young et al. 1978), which were used to assess affective symptoms.

Data analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the study population, including demographic variables and clinical characteristics.

After testing normality using Shapiro–Wilk tests and homoscedasticity using the Levene test, between-group comparisons of categorical variables were performed using χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, whenever ≥1 cell contained ≤5 patients. For comparison of continuous variables, we performed the pertinent analyses using t-test for normally distributed variables and Kruskal–Wallis test and Mann–Whitney U-tests for non-normally distributed variables, for the 3-group omnibus test, and post hoc pairwise comparisons, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 21 for Windows software (IBM). Significance level was set at alpha = 0.05, and all tests were two-tailed.

Results

Demographics and comorbidities

Altogether, 403 help-seeking adolescents and their guardians or legal representatives were consented into AMDPS. Applying the specific inclusion criteria for this report, 76 adolescent inpatients were included (BD-I = 24; BD-NOS = 29; MD-NOS = 23). Table 1 provides the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. The average age of participants was 15.6 ± 1.4 years (range = 12–18 years), the average duration of education was 9.7 ± 1.4 years, 59.2% were female, and 51.4% were white, without significant between-group differences. Comorbidities were frequent in all three groups, again, without significant between-group differences, including mainly disruptive behavior disorders (55.3%), anxiety disorders (40.8%), personality disorder traits (25.0%), and substance use disorders (17.1%) according to the KSADS.

Table 1.

Demographic, Illness and Treatment Variables

| |

Total (n = 76), n (%) | BD-I (n = 24), n (%) | BD-NOS (n = 29), n (%) | MD-NOS (n = 23), n (%) | p value | Pairwise group comparison |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD-I vs. BD-NOS | BD-I vs. MD-NOS | BD-NOS vs. MD-NOS | ||||||

| Demographic variables | ||||||||

| Male sex, n (%) | 31 (40.8) | 9 (37.5) | 10 (34.5) | 12 (52.2) | 0.403 | |||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 15.6 ± 1.4 | 15.4 ± 1.4 | 15.9 ± 1.4 | 15.4 ± 1.4 | 0.319 | |||

| Years of education (mean ± SD) | 9.7 ± 1.4 | 9. 4 ± 1.5 | 10 ± 1.4 | 9.7 ± 1.4 | 0.385 | |||

| Race, n (%) | 0.614 | |||||||

| White | 38 (51.4) | 11 (47.8) | 13 (44.8) | 14 (63.6) | ||||

| Black or African American | 18 (24.3) | 7 (30.4) | 9 (31.0) | 2 (9.1) | ||||

| Mixed | 14 (18.4) | 4 (17.4) | 6 (20.7) | 4 (18.2) | ||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 4 (5.4) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (3.4) | 2 (9.1) | ||||

| Psychopathology, median (Q1, Q3) | ||||||||

| MADRS | 27 (18, 35) | 24.5 (15.5, 34.8) | 31 (27, 36.8) | 19 (8, 28) | 0.006 | n.s. | n.s. | 0.001 |

| YMRS | 13 (7.5, 22) | 13 (7, 31) | 15 (3.8, 24.3) | 11.5 (8.8, 16) | 0.64 | |||

| GAF | 21 (17, 40) | 21 (19.3, 28.8) | 20 (10, 42) | 30 (20, 42) | 0.306 | |||

| CGI-S | 4 (3, 4) | 5 (4, 5) | 4 (3, 5) | 4 (3, 5) | 0.01 | n.s. | 0.003 | n.s. |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||||

| Personality disorder traits | 19 (25.0) | 6 (25.0) | 10 (34.5) | 3 (13.0) | 0.208 | |||

| Borderline personality traits | 15 (19.7) | 4 (16.7) | 9 (31.0) | 2 (8.7) | 0.119 | |||

| Other personality traits | 6 (7.9) | 2 (8.3) | 3 (10.3) | 1 (4.4) | 0.725 | |||

| Anxiety disorders | 31 (40.8) | 10 (41.7) | 12 (41.4) | 9 (39.1) | 0.981 | |||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 9 (11.8) | 4 (16.7) | 4 (13.8) | 1 (4.4) | 0.391 | |||

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.7) | 0.094 | |||

| PTSD | 5 (6.6) | 2 (8.3) | 2 (6.9) | 1 (4.4) | 0.856 | |||

| Panic disorder | 17 (22.4) | 6 (25.0) | 8 (27.6) | 3 (13.0) | 0.427 | |||

| Social phobia | 15 (19.7) | 4 (16.7) | 5 (17.24) | 6 (26.1) | 0.656 | |||

| Disruptive behavior disorders | 42 (55.3) | 10 (41.7) | 18 (62.1) | 14 (60.9) | 0.268 | |||

| ADHD | 27 (35.5) | 7 (29.2) | 10 (34.5) | 10 (43.5) | 0.585 | |||

| Conduct disorder | 10 (13.2) | 2 (8.3) | 5 (17.2) | 3 (13.0) | 0.634 | |||

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 18 (23.7) | 5 (20.8) | 6 (20.7) | 7 (30.4) | 0.66 | |||

| Disruptive behavior disorder NOS | 6 (7.9) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (6.9) | 3 (13.0) | 0.512 | |||

| Substance use disorders | 13 (17.1) | 2 (8.3) | 6 (20.7) | 5 (21.7) | 0.384 | |||

| Alcohol use disorder | 7 (9.2) | 1 (4.2) | 3 (10.3) | 3 (13.0) | 0.555 | |||

| Cannabis use disorder | 11 (14.5) | 1 (4.2) | 5 (17.24) | 5 (21.7) | 0.200 | |||

| Eating disorders | 10 (13.2) | 5 (20.8) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (8.7) | 0.399 | |||

| Enuresis | 7 (9.2) | 2 (8.3) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (8.7) | 0.964 | |||

| Pharmacotherapy: Admission, n (%) | ||||||||

| Antipsychotics | 55 (72.4) | 20 (83.3) | 19 (65.5) | 16 (69.6) | 0.331 | |||

| Typical antipsychotics | 3 (3.9) | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.3) | 0.298 | |||

| Atypical antipsychotic | 52 (68.4) | 18 (75.0) | 19 (65.5) | 15 (65.2) | 0.704 | |||

| Antidepressants | 27 (35.5) | 5 (20.8) | 11 (37.9) | 11 (47.8) | 0.146 | |||

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 23 (30.3) | 5 (20.8) | 9 (31) | 9 (39.1) | 0.391 | |||

| Bupropion | 3 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.9) | 1 (4.3) | 0.436 | |||

| Others | 4 (5.3) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (3.4) | 2 (8.7) | 0.673 | |||

| Mood stabilizers | 23 (30.3) | 7 (29.2) | 7 (24.1) | 9 (39.1) | 0.500 | |||

| Lithium | 17 (22.4) | 6 (25) | 3 (10.3) | 8 (34.8) | 0.103 | |||

| Valproate | 7 (9.2) | 2 (8.3) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (8.7) | 0.964 | |||

| Lamotrigine | 4 (5.3) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (6.9) | 1 (4.3) | 0.882 | |||

| Other mood stabilizers | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.9) | 0 (0) | 0.189 | |||

| Anxiolytics | 8 (10.5) | 4 (16.7) | 3 (10.3) | 1 (4.3) | 0.388 | |||

| ADHD medications | 9 (11.8) | 1 (4.2) | 4 (13.8) | 4 (17.4) | 0.343 | |||

| Pharmacotherapy: discharge, n (%) | ||||||||

| Antipsychotics | 50 (65.8) | 19 (79.2) | 18 (62.1) | 13 (56.5) | 0.227 | |||

| Typical antipsychotics | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | n.a. | |||

| Atypical antipsychotics | 50 (65.8) | 19 (79.2) | 18 (62.1) | 13 (56.5) | 0.227 | |||

| Antidepressants | 15 (19.7) | 5 (20.8) | 3 (10.3) | 7 (30.4) | 0.193 | |||

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 12 (15.8) | 4 (16.7) | 2 (6.9) | 6 (26.1) | 0.168 | |||

| Bupropion | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (4.3) | 0.610 | |||

| Others | 2 (2.6) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.3) | 0.530 | |||

| Mood stabilizers | 33 (43.4) | 16 (66.7) | 9 (31.0) | 8 (34.8) | 0.020 | 0.010 | 0.029 | n.s. |

| Lithium | 27 (35.5) | 14 (58.3) | 6 (20.7) | 7 (30.4) | 0.014 | 0.005 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Valproate | 7 (9.2) | 2 (8.3) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (8.7) | 0.964 | |||

| Lamotrigine | 4 (5.3) | 3 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.3) | 0.124 | |||

| Anxiolytics | 6 (7.9) | 2 (8.3) | 3 (10.3) | 1 (4.3) | 0.725 | |||

| ADHD medications | 5 (6.6) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (8.7) | 0.819 | |||

Bold values indicate p < 0.05 for between-groups analysis. Italic values indicate diagnostic categories that include the subsequent diagnoses.

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; BD-I, bipolar disorder type I; BD-NOS, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions Scale; GAF, global assessment of functioning; MADRS, Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MD-NOS, mood disorder not otherwise specified; n.a., not applicable; n.s., not significant; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

Psychopathology at time of admission

The median CGI-S score was 4 or “moderate” [interquartile range (IQR) = 3, 4; p = 0.01], with greater illness severity for BD-I versus MD-NOS (p = 0.003). The median baseline GAF scale score upon admission was low, that is, 21 (IQR = 17, 40), without significant group differences (p = 0.31). The median Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score (27, IQR = 18, 35) indicated greater depressive symptom load than the relatively lower median Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score (13, IQR = 7.5, 22) (with each scale having a possible range of 0–60 points). Groups did not differ at the time of assessment as inpatients regarding YMRS scores (p = 0.65), whereas MDRS scores differed significantly (p = 0.006), with BD-NOS having higher depression ratings than MD-NOS (p = 0.001).

Lifetime subsyndromal symptoms assessed with the BPSS-P

Prevalence of symptoms at “moderate” or higher severity

The prevalence of BPSS-P items rated at moderate or higher severity are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Prevalence of BPSS-P Items Rated at Moderate or Higher Severity

| |

Total (n = 76), n (%) | BD-I (n = 24), n (%) | BD-NOS (n = 29), n (%) | MD-NOS (n = 23), n (%) | p value | Pairwise group comparison |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD-I vs. BD-NOS | BD-I vs. MD-NOS | BD-NOS vs. MD-NOS | ||||||

| BPSS-P mania symptoms | ||||||||

| 1. Mood elevation | 49 (64.5) | 23 (95.8) | 20 (69.0) | 6 (26.1) | <0.0001 | 0.013 | <0.0001 | 0.002 |

| 2. Irritability | 71 (93.4) | 23 (95.8) | 27 (93.1) | 21 (91.3) | 0.819 | |||

| 3. Inflated self-esteem/grandiosity | 20 (26.3) | 13 (54.2) | 7 (24.1) | 0 (0) | <0.0001 | 0.025 | <0.0001 | 0.011 |

| 4. Decreased need for sleep | 38 (50) | 18 (75) | 14 (48.3) | 6 (26.1) | 0.004 | 0.048 | 0.001 | n.s. |

| 5. Over-talkativeness | 53 (69.7) | 19 (79.2) | 26 (89.7) | 8 (34.8) | <0.0001 | n.s. | 0.002 | <0.0001 |

| 6. Racing thoughts/flight of ideas | 49 (65.3) | 22 (91.7) | 19 (65.5) | 8 (36.4) | <0.0001 | 0.024 | <0.0001 | 0.039 |

| 7. Distractibility | 54 (71.1) | 19 (79.2) | 23 (79.3) | 12 (52.2) | 0.057 | |||

| 8. Increased energy/goal-directed activity | 36 (47.4) | 21 (87.5) | 11 (37.9) | 4 (17.4) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | n.s. |

| 9. Increased psychomotor activity | 47 (61.8) | 19 (79.2) | 17 (58.6) | 11 (47.8) | 0.078 | |||

| 10. Reckless or dangerous behavior | 27 (35.5) | 8 (33.3) | 13 (44.8) | 6 (26.1) | 0.361 | |||

| BPSS-P depression symptoms | ||||||||

| 1. Depressed mood | 62 (81.6) | 22 (91.7) | 24 (82.8) | 16 (69.6) | 0.145 | |||

| 2. Anhedonia | 45 (60.0) | 18 (75.0) | 20 (69.0) | 7 (31.8) | 0.005 | n.s. | 0.003 | 0.008 |

| 3. Decreased appetite | 19 (25.7) | 9 (39.1) | 8 (27.6) | 2 (9.1) | 0.067 | |||

| 4. Increased appetite | 13 (17.3) | 7 (30.4) | 4 (13.8) | 2 (8.7) | 0.122 | |||

| 5. Insomnia | 35 (46.1) | 13 (54.2) | 16 (55.2) | 6 (26.1) | 0.071 | |||

| 6. Hypersomnia | 17 (22.4) | 9 (37.5) | 6 (20.7) | 2 (8.7) | 0.058 | |||

| 7. Decreased psychomotor activity | 22 (29.3) | 11 (47.8) | 10 (34.5) | 1 (4.3) | 0.004 | n.s. | 0.001 | 0.008 |

| 8. Decreased energy | 44 (57.9) | 15 (62.5) | 22 (75.9) | 7 (30.4) | 0.004 | n.s. | 0.028 | 0.001 |

| 9. Worthlessness/guilt | 47 (61.8) | 18 (75.0) | 22 (75.9) | 7 (30.4) | 0.001 | n.s. | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| 10. Decreased concentration | 46 (62.2) | 16 (66.7) | 21 (75.0) | 9 (40.9) | 0.041 | n.s. | n.s. | 0.015 |

| 11. Indecision | 23 (30.7) | 8 (33.3) | 9 (31.0) | 6 (27.3) | 0.904 | |||

| 12. Suicidality | 52 (69.3) | 17 (70.8) | 22 (75.9) | 13 (59.1) | 0.429 | |||

| BPSS-P general symptoms | ||||||||

| 1. Mood lability | 54 (71.1) | 20 (83.3) | 24 (82.8) | 10 (43.5) | 0.002 | n.s. | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| 2. Oppositionality | 34 (45.9) | 10 (41.7) | 12 (44.4) | 12 (52.2) | 0.756 | |||

| 3. Anger/aggressiveness | 51 (69.9) | 15 (62.5) | 20 (74.1) | 16 (72.7) | 0.628 | |||

| 4. Anxiety | 40 (54.8) | 16 (66.7) | 13 (50.0) | 11 (47.8) | 0.357 | |||

| 5. Self-injurious behavior | 39 (52.7) | 12 (50) | 18 (66.7) | 9 (39.1) | 0.144 | |||

| 6. Obsessions and compulsions | 5 (6.9) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (8.7) | 0.739 | |||

Bold values indicate p < 0.05 for between-groups analysis.

BD-I, bipolar disorder type I; BD-NOS, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified; BPSS-P, bipolar prodrome symptom scale—prospective; MD-NOS, mood disorder not otherwise specified; n.s., not significant.

BPSS-P Mania Index

The most frequent mania-like symptoms rated at moderate or higher severity in the whole sample was irritability (93.4%), followed by distractibility (71.1%). As for BD-I, the most frequent symptoms were irritability (95.8%), mood elevation (95.8%), and racing thoughts/flight of ideas (91.7%). Conversely, patients with BD-NOS presented the highest rates of irritability (93.1%), over talkativeness (89.7%), and distractibility (79.3%) in this sample. As for MD-NOS, the most frequent symptoms were irritability (91.3%), distractibility (52.2%), and increased psychomotor activity (47.8%) (Table 2).

The three groups differed in at least one group comparison on 6 of the 10 BPSS-P mania index items, without differences for irritability (p = 0.82), distractibility (p = 0.057), increased psychomotor activity (p = 0.078), and reckless/dangerous behavior (p = 0.36). Specifically, the following symptoms of mania were significantly more frequent in BD-I versus BD-NOS and MD-NOS: mood elevation (p = 0.013; p < 0.0001), inflated self-esteem/grandiosity (p = 0.025; p < 0.0001), decreased need for sleep (p = 0.048; p = 0.004), racing thoughts (p = 0.024; p < 0.0001), and increased energy/goal directed activity (p < 0.0001 each). In addition, the following symptoms of mania were significantly more frequent in BD-NOS versus MD-NOS: mood elevation (p = 0.002), inflated self-esteem/grandiosity (p = 0.011), over-talkativeness (<0.0001), and racing thoughts/flight of ideas (p = 0.039) (Table 2).

BPSS-P Depression Index

The entire sample reported sub-/syndromal symptoms of depression as well. The following symptoms of depression rated at moderate or higher severity were most frequently reported: depressed mood (81.6%) and suicidality (69.3%). The most frequent symptoms reported in patients with BD-I in this sample were depressed mood (91.7%), anhedonia (75.0%), and worthlessness (75.0%). Similarly, patients with BD-NOS reported high rates of depressed mood (82.8%), but also reported high rates of decreased energy (75.9%). Finally, the most frequent subsyndromal symptoms in MD-NOS were depressed mood (69.6%), suicidality (59.1%), and decreased concentration (40.9%) (Table 2).

The three groups differed in at least one group comparison on 7 of the 12 BPSS-P depression index items, without differences for depressed mood (p = 0.14), decreased appetite (p = 0.067), increased appetite (p = 0.12), insomnia (p = 0.071), hypersomnia (p = 0.058), indecision (p = 0.9), and suicidality (p = 0.43).

There were no significant differences between BD-I and BD-NOS on any of the BPSS-P depression items. Conversely, the following symptoms of depression were significantly more frequent in BD-I versus MD-NOS: anhedonia (p = 0.003), decreased psychomotor activity (p = 0.001), decreased energy (p = 0.028), worthlessness/guilt (p = 0.002). Furthermore, the following symptoms of depression were significantly more frequent in BD-NOS versus MD-NOS: anhedonia (p = 0.008), decreased psychomotor activity (p = 0.008), decreased energy (p = 0.001), worthlessness/guilt (p = 0.001), and decreased concentration (p = 0.015) (Table 2).

BPSS-P General Symptom Index

The following general symptoms at moderate or higher severity were the most frequent: mood lability (71.1%) and anger/aggressiveness (69.9%). The three groups only differed regarding 1 of the 6 BPSS-P general symptoms, mood lability (p = 0.002). In the BD-I (83.3%) and BD-NOS (82.8%) groups, the proportion of patients with relevant mood lability did not differ significantly, but each BD-I and BD-NOS had significantly higher frequencies of mood lability versus MD-NOS (43.5%; BD-I vs. MD-NOS: p = 0.004, BD-NOS vs. MD-NOS: p = 0.003) (Table 2).

Severity of symptom ratings

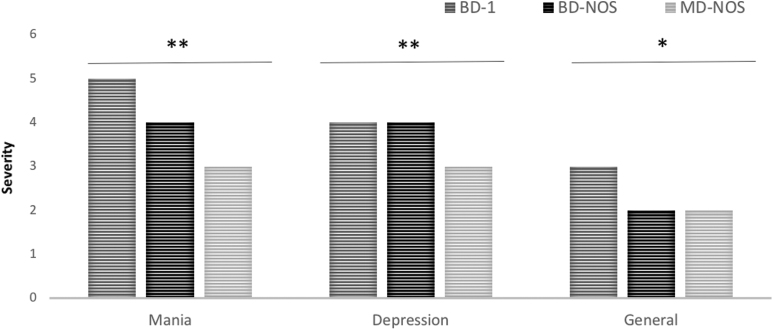

In Table 3 and Figure 1, details regarding the severity ratings of the different affective symptoms are given.

Table 3.

Severity of BPSS-P Items

| |

Total (n = 76), median (Q1–Q3) | BD-I (n = 24), median (Q1–Q3) | BD-NOS (n = 29), median (Q1–Q3) | MD-NOS (n = 23), median (Q1–Q3) | p value | Pairwise group comparison |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD-I vs. BD-NOS | BD-I vs. MD-NOS | BD-NOS vs. MD-NOS | ||||||

| BPSS-P mania symptoms | 4 (1–5) | 5 (4–6) | 4 (2–5) | 3 (0–4) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| 1. Mood elevation | 4 (3–5) | 5 (5–6) | 4 (3–5) | 3 (1–4) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.009 |

| 2. Irritability | 5 (4.25–6) | 5.5 (5–6) | 5 (4.5–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.081 | |||

| 3. Inflated self-esteem/grandiosity | 2 (0–4) | 4 (1.25–6) | 1 (0–3.5) | 1 (0–2) | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.001 | n.s. |

| 4. Decreased need for sleep | 3.5 (0–6) | 5 (3.25–6) | 3 (0–6) | 0 (0–4) | 0.003 | n.s. | 0.001 | n.s. |

| 5. Over-talkativeness | 5 (3–5) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–5) | 3 (1–4) | <0.0001 | n.s. | 0.001 | <0.0001 |

| 6. Racing thoughts/flight of ideas | 4 (2–5) | 5 (4.25–6) | 4 (2–5) | 2.5 (0.75–4) | <0.0001 | 0.024 | <0.0001 | 0.048 |

| 7. Distractibility | 5 (3–5) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–5) | 4 (1–5) | 0.01 | n.s. | 0.007 | 0.012 |

| 8. Increased energy/goal-directed activity | 3 (2–5) | 5 (4–6) | 3 (2–4) | 1 (0–3) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.004 |

| 9. Increased psychomotor activity | 4 (3–5) | 4 (4–6) | 4 (2.5–5) | 3 (1–4) | 0.017 | n.s. | 0.005 | n.s. |

| 10. Reckless or dangerous behavior | 1.5 (0–5) | 1 (0–4.75) | 2 (0–5) | 2 (0–4) | 0.82 | |||

| BPSS-P depression symptoms | 3 (0–5) | 4 (1–5) | 4 (1–5) | 2 (0–4) | <0.0001 | n.s. | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| 1. Depressed mood | 5 (4–6) | 6 (5–6) | 5 (4–6) | 4 (3–5) | 0.004 | n.s. | <0.0001 | 0.022 |

| 2. Anhedonia | 4 (3–5) | 5 (3.25–5) | 4 (3–6) | 3 (1.5–4) | 0.006 | n.s. | 0.002 | 0.015 |

| 3. Decreased appetite | 1 (0–4) | 1 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 0 (0-I) | 0.026 | n.s. | 0.036 | 0.008 |

| 4. Increased appetite | 1 (0–3) | 2 (0–4) | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–2) | 0.047 | 0.034 | 0.033 | n.s. |

| 5. Insomnia | 3 (0–5) | 4 (0–5) | 4 (2–5) | 1 (0–4) | 0.071 | |||

| 6. Hypersomnia | 1 (0–3) | 3 (0–5) | 1 (0–3) | 0 (0–3) | 0.092 | |||

| 7. Decreased psychomotor activity | 2 (0–4) | 3 (3–5) | 1 (0–4) | 0 (0–2) | 0.001 | 0.03 | <0.0001 | n.s. |

| 8. Decreased energy | 4 (1–5) | 4 (1–6) | 5 (3.5–6) | 2 (0–4) | 0.017 | n.s. | n.s. | 0.005 |

| 9. Worthlessness/guilt | 4 (1–5) | 4 (2.5–5) | 4 (3.5–5) | 3 (0–5) | 0.027 | n.s. | 0.031 | 0.013 |

| 10. Decreased concentration | 4 (1–5) | 4.5 (2.25–5) | 4 (3.25–5) | 2 (0–4) | 0.014 | n.s. | 0.016 | 0.007 |

| 11. Indecision | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0.25–4.75) | 2 (1–4) | 1.5 (0–4) | 0.350 | |||

| 12. Suicidality | 6 (2–6) | 5.5 (3–6) | 6 (3–6) | 4.5 (0–6) | 0.185 | |||

| BPSS-P General symptoms | 4 (0–5) | 4 (0–5) | 4 (1–5) | 3 (1–5) | 0.038 | n.s. | n.s. | 0.011 |

| 1. Mood lability | 5 (3–6) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 3 (0–5) | 0.001 | n.s. | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| 2. Oppositionality | 3 (1.75–5) | 3 (0–4) | 3 (2–5) | 4 (2–5) | 0.513 | |||

| 3. Anger/aggressiveness | 5 (3–5.5) | 5 (3–6) | 4 (3–5) | 5 (3–5.25) | 0.949 | |||

| 4. Anxiety | 4 (2–5) | 4.5 (3–5.75) | 3.5 (1.75–5) | 2 (1–5) | 0.044 | 0.031 | 0.031 | n.s. |

| 5. Self-injurious behavior | 4 (0–5) | 2.5 (0–4.75) | 4 (0.5–6) | 3 (0–4) | 0.035 | n.s. | n.s. | 0.012 |

| 6. Obsessions and compulsions | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | 0.959 | |||

Bold values indicate p < 0.05 for between-groups analysis.

Severity is rated on an ordinal scale: 0 = absent, 1 = questionably present, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = moderately severe, 5 = severe, 6 = extreme.

BD-I, bipolar disorder type I; BD-NOS, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified; BPSS-P, bipolar prodrome symptom scale-prospective; MD-NOS, mood disorder not otherwise specified; n.s., not significant; Q1, first quartile (P25); Q3, third quartile (P75).

FIG. 1.

Severity of BPSS-P Mania, Depression and General Symptom Index subthreshold symptoms. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.0001. BD-I, bipolar disorder type I; BD-NOS, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified; BPSS-P, bipolar prodrome symptom scale-prospective; MD-NOS, mood disorder not otherwise specified.

BPSS-P_mania index

Pooled together, the severity of sub-/syndromal symptoms of mania differed significantly across the 3 diagnostic groups (p < 0.0001), being higher in patients with BD-I (median 5—severe–worst month lifetime; p < 0.0001) versus BD-NOS (median = 4, p < 0.0001) and MD-NOS (median = 3, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1). The three groups differed in at least one group comparison on 8 of the 10 mania index items, except for irritability (p = 0.081) and reckless/dangerous behavior (p = 0.82). Specifically, compared with BD-NOS, BD-I patients scored significantly more severe on 4 of the 10 mania items (mood elevation, inflated self-esteem/grandiosity, racing thoughts/flight of ideas, and increased energy/goal-directed activity). Compared with MD-NOS, BD-I patients scored significantly more severe on 8 of the 10 mania items (mood elevation, inflated self-esteem/grandiosity, decreased need for sleep, over-talkativeness, racing thoughts/flight of ideas, distractibility, increased energy/goal-directed activity, and increased psychomotor activity). Finally, compared with MD-NOS, BD-NOS patients scored significantly more severe on 5 of the 10 mania items (mood elevation, over-talkativeness, racing thoughts/flight of ideas, distractibility, and increased energy/goal-directed activity) (Table 3).

BPSS-P_depression index

Pooled together, the severity of sub-/syndromal symptoms of depression was significantly higher (p < 0.0001) in each BD-I and BD-NOS, which had similar median severity scores of 4 (“moderately severe”) versus MD-NOS (median = 2) (Fig. 1). The three groups differed in at least one group comparison on 8 of the 12 depression index items, without differences for insomnia (p = 0.071), hypersomnia (p = 0.092), indecision (p = 0.35), and suicidality (p = 0.18). Specifically, compared with BD-NOS, BD-I patients scored significantly more severe on 2 of the 12 depression items (increased appetite and decreased psychomotor activity). Compared with MD-NOS, BD-I patients scored significantly more severe on 7 of the 12 depression items (depressed mood, anhedonia, decreased appetite, increased appetite, decreased psychomotor activity, worthlessness/guilt, and decreased concentration). Finally, compared with MD-NOS, BD-NOS patients scored significantly more severe on 6 of the 12 depression items (depressed mood, anhedonia, decreased appetite, decreased energy, worthlessness/guilt, and decreased concentration) (Table 3).

BPSS-P General Symptom Index

Pooled together, BPSS-P general symptom severity differed across the three diagnostic groups (p = 0.038), but in post hoc pairwise comparisons only BD-NOS had significantly higher median scores than MD-NOS (4 vs. 3, p = 0.011). At least one group comparison was significantly different in three of the six BSS-P general symptom items, including mood lability (BD-I and BD-NOS > MD-NOS), anxiety (BD-I > BD-NOS and MD-NOS), and self-injurious behavior (BD-NOS > MD-NOS) (Table 3).

Duration of symptoms

Subthreshold symptoms of mania and general symptoms in the BD-NOS and MD-NOS groups, and subthreshold symptoms of depression in the MD-NOS group are given in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4.

Duration of BPSS-P Mania and General Symptoms Rated at Moderate or Higher Severity Since Onset (Weeks)

| BD-NOS (n = 29), median (Q1–Q3) | MD-NOS (n = 23), median (Q1–Q3) | |

|---|---|---|

| BPSS-P mania symptoms | 20.4 (12.1–30.7) | 11.7 (6.1–28.4) |

| 1. Mood elevation | 20.1 (8.3–31.9) | 12 (7.3–40.3) |

| 2. Irritability | 20.4 (12.1–30.7) | 10.2 (5.3–14.6) |

| 3. Inflated self-esteem/grandiosity | 16.4 (0.7–18.2) | 4.9 (0.54–43.6) |

| 4. Decreased need for sleep | 27.4 (13.7–32.9) | 14.57 (11.21–48.07) |

| 5. Over-talkativeness | 20.3 (13–30.9) | 14.43 (5–34.07) |

| 6. Racing thoughts/flight of ideas | 21.4 (15.4–27.7) | 12.71 (8.07–37.75) |

| 7. Distractibility | 22.4 (12.7–31.1) | 8.71 (5.86–12.86) |

| 8. Increased energy/goal-directed activity | 23.3 (7.5 33.2) | 34.64 (28.43–40.86) |

| 9. Increased psychomotor activity | 24.9 (15–31.6) | 11.86 (7.86–18.14) |

| 10. Reckless or dangerous behavior | 16.4 (7.4–20.9) | 8.43 (2.57–14.21) |

| BPSS-P general symptoms | 21.6 (14.9–30.7) | 12.0 (7–28.4) |

| 1. Mood lability | 20.4 (8.3–30.3) | 12 (6.1–28.4) |

| 2. Oppositionality | 22 (16.6–30.9) | 8.6 (3.7–21) |

| 3. Anger/aggressiveness | 21 (8.3–31.2) | 10.2 (5.3–18.1) |

| 4. Anxiety | 25.5 (18.5–32) | 13.2 (8.5–37.7) |

| 5. Self-injurious behavior | 21 (15.6–30.1) | 24.1 (10.1–46) |

| 6. Obsessions and compulsions | 15.4 (1.1–17.9) | 11.6 (8.7–14.4) |

BD-NOS, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified; BPSS-P, bipolar prodrome symptom scale-prospective; MD-NOS, mood disorder not otherwise specified; Q1, first quartile (P25); Q3, third quartile (P75).

Table 5.

Duration of BPSS-P Depressive Symptoms Rated at Moderate or Higher Severity Since Onset (Weeks)

| MD-NOS (n = 23) |

|

|---|---|

| Median (Q1–Q3) | |

| BPSS-P depression symptoms | 21.6 (13.3–29.9) |

| 1. Depressed mood | 21.6 (13.3–30.7) |

| 2. Anhedonia | 21 (12.4–30.5) |

| 3. Decreased appetite | 20.3 (4.2–29.1) |

| 4. Increased appetite | 15.7 (8.6–20.7) |

| 5. Insomnia | 22.4 (12.1–29.9) |

| 6. Hypersomnia | 20.4 (17.1–31.6) |

| 7. Decreased psychomotor activity | 24.9 (18.3–32.2) |

| 8. Decreased energy | 21.6 (12.7–30.3) |

| 9. Worthlessness/guilt | 21.6 (12.1–30.7) |

| 10. Decreased concentration | 23.6 (13–30.9) |

| 11. Indecision | 20.9 (14.9–27.1) |

| 12. Suicidality | 21.6 (14.9–28.4) |

BPSS-P, bipolar prodrome symptom scale-prospective; MD-NOS, mood disorder not otherwise specified; Q1, first quartile (P25); Q3, third quartile (P75).

The median duration of subthreshold mania symptoms in BD-NOS was 20.4 weeks, with the shortest duration for inflated self-esteem/grandiosity and reckless or dangerous behavior (16.4 weeks, each) and the longest duration for decreased need for sleep (27.4 weeks). As for general symptoms, the median duration was 21.6 weeks, with the shortest duration for obsessions and compulsions (15.4 weeks) and the longest duration for anxiety (25.5 weeks) (Table 4).

The median duration of subthreshold symptoms of mania in MD-NOS was 11.7 weeks, with the shortest duration for inflated self-esteem/grandiosity (4.9 weeks) and longest duration for increased energy/goal-directed activity (34.6 weeks). The median duration of depressive symptoms in this group was 21.6 weeks, ranging from 15.7 weeks (increased appetite) to 24.9 weeks (decreased psychomotor activity). The median duration of general symptoms was 12 weeks, with the shortest duration for oppositionality (8.6 weeks) and the longest duration for self-injurious behavior (24.1 weeks) (Tables 4 and 5).

Comparing the durations of subthreshold symptoms, the median duration of subthreshold mania symptoms in BD-NOS was significantly longer than in the MD-NOS group (20.4 vs. 11.7 weeks, p = 0.002). The same was true for the general symptom duration (21.6 vs. 12.0 weeks, p = 0.022). Within the MD-NOS group, the duration of subthreshold depressive symptoms (21.6 weeks) was significantly longer than the duration of subthreshold mania (11.7 weeks, p = 0.015) and general symptoms (12.0 weeks, p = 0.012), whose duration was not different from each other (p = 0.82).

Pharmacologic treatment

The most used psychotropic medications upon admission were antipsychotics (72.4%, p = 0.331), followed by antidepressants (35.5%, p = 0.146) and mood stabilizers (30.3%, p = 0.500) (Table 1). The most prescribed psychotropic medications upon discharge were antipsychotics (65.8%, p = 0.227) and mood stabilizers [43.4%, p = 0.020; BD-I (66.7%) vs. BD-NOS (31.0%): p = 0.01; BD1 vs. MD-NOS (34.8%): p = 0.029], followed by antidepressants (19.7%, p = 0.193). Whereas the reduction from admission to discharge in antipsychotic prescribing (p = 0.38) and the increase in mood stabilizer prescribing (p = 0.09) were not statistically significant at overall group level, the decrease in antidepressant prescribing (p = 0.029) was statistically significant. Within individual diagnostic groups, the significant decrease in antidepressant prescribing was apparent only in the BD-NOS group (37.9% to 10.3%, p = 0.014), whereas there was a significant increase in mood stabilizer treatment in the BD-I group (29.2% to 66.7%, p = 0.009).

Discussion

Psychopathology

This study evaluated a sample of adolescent patients diagnosed with a BD-spectrum disorder who had been admitted to a psychiatric unit. In all three diagnostic groups, psychopathology measures (CGI-S, MADRS) suggested moderate severity of psychopathology, with greater depression than mania scores. These findings are consistent with previous studies, where symptoms in youth with BD-spectrum disorders were considered disabling (Hernandez et al. 2017).

In our sample, patients diagnosed with BD-I and BD-NOS did not differ on depression severity, and BD-NOS scored higher on the MADRS scale compared with MD-NOS, which is consistent with the previous literature, showing important rates of depression in BD-NOS compared with other psychiatric diagnoses including major depression (Towbin et al. 2013). Conversely, overall, YMRS scale scores were only about half as severe as scores on the MADRS (with both scales ranging from 0 to 60 points), and none of the three diagnostic groups differed from each other. In contrast to moderate illness and depressive symptom severity, functional levels, measured with the GAF scale, were severely impaired in all three groups in our sample.

Comorbidity

Comorbidities, as previously described in patients with BD-spectrum disorders (Shain 2012; Muneer 2016), especially in adolescents (Shain 2012), were very highly prevalent in our sample, particularly disruptive behavior disorders and anxiety disorders. With one third, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was the most frequent individual condition comorbid with BD-spectrum disorders. This finding is consistent with some (Wingo and Ghaemi 2007; Torres et al. 2017), but different from other studies conducted in adults where anxiety disorders (particularly panic attacks) were the most common comorbid diagnoses (Merikangas et al. 2011).

Moreover, ADHD was not only the most common comorbidity in BD-I, but also in BD-NOS and, especially, in MD-NOS. Similarly, in the COBY study, ADHD was the most common comorbid condition in BD-NOS, both in nonconverters (63.6%) and in those that converted to BD-I (61.9%) (Axelson et al. 2011). Detecting and managing comorbidities in youth with BD-spectrum disorders is important, as in addition to their own burden, worsening of these conditions could trigger a mood episode recurrence (Yen et al. 2016).

Subsyndromal symptoms

In our sample, using the BPSS-P, we observed important rates (>90%) of mania-like and depression symptoms. This thorough approach enabled the detection of subtle and subthreshold symptoms of different severity and suggests that the BPSS-P can be a useful instrument to detect symptomatology below the threshold of syndromal YMRS ratings and anchors (Correll et al. 2014). Previous studies have suggested that a greater severity of subthreshold mania-like symptoms might imply greater risk of developing a full episode of mania (Tijssen et al. 2010; Mesman et al. 2013; Hafeman et al. 2016; Duffy et al. 2017; Goodday et al. 2017). This risk of BD development might also be increased by comorbid conditions, such as ADHD and anxiety disorders (Mesman et al. 2013) (Hafeman et al. 2016) that can also delay symptom remission (Bukh et al. 2016). Unfortunately, the validity of the clinical diagnosis of BD is often suboptimal, especially in youth (Dilsaver and Akiskal 2005) and the presence of syndromal BD is under-recognized, which complicates identification of high-risk youth and timely targeted preventative interventions.

The median duration of subthreshold symptoms of mania was 5 months in the BD-NOS group and 3 months in the MD-NOS group, whereas the median duration of depressive symptoms was 5 months. These are significant amounts of time, especially for adolescents who need to reach relevant social and educational as well as biological milestones and who are at risk of developing BD-I (Birmaher et al. 2006). Early recognition and appropriate intervention of BD-spectrum disorders, and prevention are urgently needed, indicated by data showing that longer delays before first treatment in BD have been associated with longer and more severe depressive phases, more comorbid disorders, and less time free of symptoms in adolescence or early adulthood (Birmaher et al. 2006). Thus, the ability to detect signs and symptoms that could be part of a mania prodrome and to characterize frequencies, severity, and duration of such symptoms is critical for BD prevention and management, as identifying and treating illness early in its time course may be associated with better prognosis (Berk et al. 2007).

Unfortunately, different from schizophrenia, subthreshold symptom detection models for youth at-risk for BD, which would allow earlier intervention and reduction in overall morbidity and mortality, have not been implemented widely (Hunt et al. 2016). Nevertheless, it is hoped that a multidisciplinary approach, including psychoeducation and management of substance misuse and other clinically relevant psychiatric and physical comorbidities (Martin and Smith 2013) could alter the trajectory of mood disorder pathology (Walker et al. 2014) and make early intervention and prevention in BD feasible, including in adolescents (Arango et al. 2018).

However, the field still needs to figure out the specificity of putatively prodromal symptoms for mania in adolescence where many maturational and adaptational processes take place, and mood and affective shifts are observed (Hauser and Correll 2013).

Pharmacologic treatment

Of note, despite the fact that less than one-third of the entire sample had a diagnosis of BD-I, antipsychotics were the most commonly clinically prescribed psychotropic drug class, being prescribed to almost three-quarters of the sample upon admission, without significant differences between the three BD-spectrum groups. Although, at least for pediatric patients, second-generation antipsychotics seem to be more efficacious than conventional mood stabilizers for mania (Correll et al. 2010), this widespread use of antipsychotics even for BD-NOS and MD-NOS is concerning, given the well-known adverse effects, including cardiovascular effects (Geller et al. 2012; Arango et al. 2014). From admission to discharge, the antipsychotic prescribing decreased nonsignificantly to two-thirds, but there was a significant decrease in antidepressant prescribing in the BD-NOS group (37.9% to 10.3%, p = 0.014), whereas there was a significant increase in mood stabilizer treatment in the BD-I group (29.2% to 66.7%, p = 0.009).

The decrease in antidepressant treatment in the BD-NOS group may have been owing to a recognition of BD-risk and that antidepressants could worsen this risk (Luft et al. 2018); however, we did not collect data on reasons for medication changes during the hospital stay. The significant increase in mood stabilizer treatment in BD-I patients seems to suggest that combination treatments with antipsychotics and mood stabilizers were chosen in this sample in need for hospitalization, likely based on the premise that antipsychotic mood stabilizer cotreatment may be superior to antipsychotic monotherapy. Finally, the decrease in the use of ADHD medication from admission to discharge could indicate that some of the symptoms that patients previously diagnosed with ADHD presented could have been secondary to prodopaminergic treatment.

Limitations

Results of this study must be interpreted within its limitations. First, given the relatively small sample size, power to detect statistical significance was reduced and some of the findings, although not statistically significant, might be clinically relevant. Second, we focused solely on BD-I, BD-NOS, and MD-NOS patients, excluding the 9 patients with BD-II because of the limited number of such adolescents who were part of this consecutively accrued psychiatric adolescent inpatient sample. Future studies containing more youth with BD-II and/or cyclothymia are hoped to shed further light on the cross-sectional differences to other subsyndromal and syndromal mood disorders and their longitudinal outcomes. Third, no nonbipolar-spectrum disorder psychiatric control group was assessed for comparison. Fourth, although the K-SADS-PL is the gold standard tool for diagnosing psychiatric disorders in child and adolescent populations, some symptom collections are based on retrospective data, which may be prone to recall bias. We tried to minimize this potential problem by interviewing caretakers as well. Fifth, many patients received psychotropic medications at the time of the assessment, which could possibly have influenced our results. Sixth, because this is a cross-sectional study, we lack prospective follow-up data at this point, and we cannot conclude if characterized subthreshold symptoms are prodromal or not. Finally, we did not collect information about biological correlates of BD or reasons for medication change.

Nevertheless, despite these limitations, this is one of the few studies that carefully assessed adolescents with BD-I, BD-NOS, and MD-NOS with the same methodology and in the same study. Moreover, the focus on help-seeking individuals with a wide variety of psychopathology and psychotropic treatment is also a strength, as this reflects clinical reality in groups of patients who are at risk of developing a syndromal affective episode and disorder, increasing the generalizability and applicability of these findings. The study has further strengths including the use of structured and validated instruments for the diagnosis and assessment of syndromal and subsyndromal and putatively prodromal psychopathology. Finally, information was obtained from both patients and parents/caregivers and the time delay between symptoms' onset and data collection was still relatively short compared with other retrospective studies (especially in adults), reducing recall bias further.

Conclusions

In conclusion, youth with BD-I, BD-NOS, and MD-NOS present with considerable psychiatric comorbidity and clinical severity as well as functional impairment. Our results suggest that many youths with BD-spectrum diagnoses undergo a long symptomatic period characterized by subthreshold symptoms of the subsequent mood episode. Future studies are necessary to better characterize the BD prodrome, to determine valid and sufficiently specific clinical high-risk criteria, distinguish risk factors, endophenotypes, and comorbidities from prodromal symptomatology, elucidate predictors of conversion to BD across the lifespan, and to develop phase-specific interventions that titrate the risk of interventions to the risk of transition to mania and to functional impairment or distress.

Clinical Significance

Youth with BD-I, BD-NOS, and MD-NOS experience considerable symptomatology and are functionally impaired, with few differences observed in psychiatric comorbidity and clinical severity. Moreover, youth with BD-NOS and MD-NOS undergo a period with subthreshold manic symptoms, enabling identification and, possibly, preventive intervention of those at risk for developing BD and for suffering a new affective episode that might lead to hospitalization.

Disclosures

G.S.d.P. is supported by the Alicia Koplowitz Foundation. D.L.V. has received speaking fees from Lundbeck. C.A. has been a consultant to or has received honoraria or grants from Acadia, Ambrosseti, Gedeon Richter, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Roche, Sage, Servier, Shire, Schering Plough, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Sunovion and Takeda. C.M. has acted as consultant or participated in DMC for Janssen, Servier, Lundbeck, Nuvelution, Angelini, and Otsuka and has received grant support from European Union Funds and Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiviness. C.U.C. has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from: Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Gedeon Richter, Gerson Lehrman Group, Indivior, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, Medscape, Merck, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Servier, Sumitomo Dainippon, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva. He has provided expert testimony for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and Otsuka. He served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lundbeck, Rovi, Supernus, and Teva. He received royalties from UpToDate and grant support from Janssen and Takeda. He is also a shareholder of LB Pharma.

References

- Akiskal HS, Akiskal K, Allilaire JF, Azorin JM, Bourgeois ML, Sechter D, Fraud JP, Chatenêt-Duchêne L, Lancrenon S, Perugi G, Hantouche EG: Validating affective temperaments in their subaffective and socially positive attributes: Psychometric, clinical and familial data from a French national study. J Affect Disord 85:29–36, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J, Petukhova M, Vilagut G, Chatterji S, Heeringa S, Üstün TB, Alhamzawi AO, Viana MC, Angermeyer M, Bromet E, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, Florescu S, Gureje O, Haro JM, Hinkov H, Hu CY, Karam EG, Kovess V, Levinson D, Medina-Mora ME, Nakamura Y, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Scott KM, Tsang A, Williams DR, Kessler RC: Days out of role due to common physical and mental conditions: Results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Mol Psychiatry 16:1234–1246, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Arango C, Díaz-Caneja CM, McGorry PD, Rapoport J, Sommer IE, Vorstman JA, McDaid D, Marín O, Serrano-Drozdowskyj E, Freedman R, Carpenter W: Preventive strategies for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 5:591–604, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arango C, Fraguas D, Parellada M: Differential neurodevelopmental trajectories in patients with early-onset bipolar and schizophrenia disorders. Schizophr Bull 40 Suppl 2:S138–S146, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arango C, Giráldez M, Merchán-Naranjo J, Baeza I, Castro-Fornieles J, Alda JA, Martínez-Cantarero C, Moreno C, de Andrés P, Cuerda C, de la Serna E, Correll CU, Fraguas D, Parellada M: Second-generation antipsychotic use in children and adolescents: A six-month prospective cohort study in drug-naïve patients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 53:1179–1190, 1190.e1171–e1174, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Strober MA, Goldstein BI, Ha W, Gill MK, Goldstein TR, Yen S, Hower H, Hunt JI, Liao F, Iyengar S, Dickstein D, Kim E, Ryan ND, Frankel E, Keller MB: Course of subthreshold bipolar disorder in youth: Diagnostic progression from bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 50:1001–1016.e1003, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Dodd S, Callaly P, Berk L, Fitzgerald P, de Castella AR, Filia S, Filia K, Tahtalian S, Biffin F, Kelin K, Smith M, Montgomery W, Kulkarni J: History of illness prior to a diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder. J Affect Disord 103:181–186, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Keller M: Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63:175–183, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Ehmann M, Axelson DA, Goldstein BI, Monk K, Kalas C, Kupfer D, Gill MK, Leibenluft E, Bridge J, Guyer A, Egger HL, Brent DA: Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS-PL) for the assessment of preschool children—a preliminary psychometric study. J Psychiatr Res 43:680–686, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Goldstein BI, Axelson DA, Monk K, Hickey MB, Fan J, Iyengar S, Ha W, Diler RS, Goldstein T, Brent D, Ladouceur CD, Sakolsky D, Kupfer DJ: Mood lability among offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and community controls. Bipolar Disord 15:253–263, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie CR, Depp C, McGrath JA, Wolyniec P, Mausbach BT, Thornquist MH, Luke J, Patterson TL, Harvey PD, Pulver AE: Prediction of real-world functional disability in chronic mental disorders: A comparison of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 167:1116–1124, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukh JD, Andersen PK, Kessing LV: Rates and predictors of remission, recurrence and conversion to bipolar disorder after the first lifetime episode of depression—a prospective 5-year follow-up study. Psychol Med 46:1151–1161, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GA, Pataki C: Understanding early age of onset: A review of the last 5 years. Curr Psychiatry Rep 18:114, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton MT, Goulding SM, Walker EF: Characteristics of the Retrospectively Assessed Prodromal Period in Hospitalized Patients With First-Episode Nonaffective Psychosis: Findings From a Socially Disadvantaged, Low-Income, Predominantly African American Population. J Clin Psychiatry 71:1279–1285, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor DF, Ford JD, Pearson GS, Scranton VL, Dusad A: Early-Onset Bipolar Disorder: Characteristics and Outcomes in the Clinic. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 27:875–883, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conus P, Ward J, Lucas N, Cotton S, Yung AR, Berk M, McGorry PD: Characterisation of the prodrome to a first episode of psychotic mania: Results of a retrospective study. J Affect Disord 124:341–345, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Hauser M, Penzner JB, Auther AM, Kafantaris V, Saito E, Olvet D, Carrión RE, Birmaher B, Chang KD, DelBello MP, Singh MK, Pavuluri M, Cornblatt BA: Type and duration of subsyndromal symptoms in youth with bipolar I disorder prior to their first manic episode. Bipolar Disord 16:478–492, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Olvet DM, Auther AM, Hauser M, Kishimoto T, Carrión RE, Snyder S, Cornblatt BA: The Bipolar Prodrome Symptom Interview and Scale-Prospective (BPSS-P): Description and validation in a psychiatric sample and healthy controls. Bipolar Disord 16:505–522, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Penzner JB, Lencz T, Auther A, Smith CW, Malhotra AK, Kane JM, Cornblatt BA: Early identification and high-risk strategies for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 9:324–338, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Sheridan EM, DelBello MP: Antipsychotic and mood stabilizer efficacy and tolerability in pediatric and adult patients with bipolar I mania: A comparative analysis of acute, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Bipolar Disord 12:116–141, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilsaver SC, Akiskal HS: High rate of unrecognized bipolar mixed states among destitute Hispanic adolescents referred for “major depressive disorder”. J Affect Disord 84:179–186, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy A, Alda M, Crawford L, Milin R, Grof P: The early manifestations of bipolar disorder: A longitudinal prospective study of the offspring of bipolar parents. Bipolar Disord 9:828–838, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy A, Alda M, Hajek T, Sherry SB, Grof P: Early stages in the development of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 121:127–135, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy A, Vandeleur C, Heffer N, Preisig M: The clinical trajectory of emerging bipolar disorder among the high-risk offspring of bipolar parents: Current understanding and future considerations. Int J Bipolar Disord 5:37, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland JA, Endicott J, Hostetter AM, Allen CR, Pauls DL, Shaw JA: A 16-year prospective study of prodromal features prior to BPI onset in well Amish children. J Affect Disord 142:186–192, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faedda GL, Marangoni C, Serra G, Salvatore P, Sani G, Vazquez GH, Tondo L, Girardi P, Baldessarini RJ, Koukopoulos A: Precursors of bipolar disorders: A systematic literature review of prospective studies. J Clin Psychiatry 76:614-U209, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faedda GL, Serra G, Marangoni C, Salvatore P, Sani G, Vazquez GH, Tondo L, Girardi P, Baldessarini RJ, Koukopoulos A: Clinical risk factors for bipolar disorders: A systematic review of prospective studies. J Affect Disord 168:314–321, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Luby JL, Joshi P, Wagner KD, Emslie G, Walkup JT, Axelson DA, Bolhofner K, Robb A, Wolf DV, Riddle MA, Birmaher B, Nusrat N, Ryan ND, Vitiello B, Tillman R, Lavori P: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Risperidone, Lithium, or Divalproex Sodium for Initial Treatment of Bipolar I Disorder, Manic or Mixed Phase, in Children and Adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69:515–528, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Merranko J, Krantz M, Garcia M, Franzen P, Levenson J, Axelson D, Birmaher B, Frank E: Early intervention for adolescents at-risk for bipolar disorder: A pilot randomized trial of Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy (IPSRT). J Affect Disord 235:348–356, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodday SM, Preisig M, Gholamrezaee M, Grof P, Angst J, Duffy A: The association between self-reported and clinically determined hypomanic symptoms and the onset of major mood disorders. Bjpsych Open 3:71–77, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grande I, Berk M, Birmaher B, Vieta E: Bipolar disorder. Lancet 387:1561–1572, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmocology - Revised. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration, NIMH, 1976 [Google Scholar]

- Hafeman D, Axelson D, Demeter C, Findling RL, Fristad MA, Kowatch RA, Youngstrom EA, Horwitz SM, Arnold LE, Frazier TW, Ryan N, Gill MK, Hauser-Harrington JC, Depew J, Rowles BM, Birmaher B: Phenomenology of bipolar disorder not otherwise specified in youth: A comparison of clinical characteristics across the spectrum of manic symptoms. Bipolar Disord 15:240–252, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafeman DM, Merranko J, Axelson D, Goldstein BI, Goldstein T, Monk K, Hickey MB, Sakolsky D, Diler R, Iyengar S, Brent D, Kupfer D, Birmaher B: Toward the Definition of a Bipolar Prodrome: Dimensional Predictors of Bipolar Spectrum Disorders in At-Risk Youths. Am J Psychiatry 173:695–704, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafeman DM, Merranko J, Goldstein TR, Axelson D, Goldstein BI, Monk K, Hickey MB, Sakolsky D, Diler R, Iyengar S, Brent DA, Kupfer DJ, Kattan MW, Birmaher B: Assessment of a person-level risk calculator to predict new-onset bipolar spectrum disorder in youth at familial risk. JAMA Psychiatry 74:841–847, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser M, Correll CU: The significance of at-risk or prodromal symptoms for bipolar I disorder in children and adolescents. Can J Psychiatry 58:22–31, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez M, Marangoni C, Grant MC, Estrada J, Faedda GL: Parental reports of prodromal psychopathology in pediatric bipolar disorder. Curr Neuropharmacol 15:380–385, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J, Schwarz CM, Nye P, Frazier E: Is there a bipolar prodrome among children and adolescents? Curr Psychiatry Rep 18:35, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janiri D, Sani G, Danese E, Simonetti A, Ambrosi E, Angeletti G, Erbuto D, Caltagirone C, Girardi P, Spalletta G: Childhood traumatic experiences of patients with bipolar disorder type I and type II. J Affect Disord 175:92–97, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:980–988, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krabbendam L, Arts B, van Os J, Aleman A: Cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A quantitative review. Schizophr Res 80:137–149, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenox RH, Gould TD, Manji HK: Endophenotypes in bipolar disorder. Am J Med Genet 114:391–406, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Cascio N, Saba R, Hauser M, Vernal DL, Al-Jadiri A, Borenstein Y, Sheridan EM, Kishimoto T, Armando M, Vicari S, Fiori Nastro P, Girardi P, Gebhardt E, Kane JM, Auther A, Carrión RE, Cornblatt BA, Schimmelmann BG, Schultze-Lutter F, Correll CU: Attenuated psychotic and basic symptom characteristics in adolescents with ultra-high risk criteria for psychosis, other non-psychotic psychiatric disorders and early-onset psychosis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 25:1091–1102, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo LE, Bearden CE, Barrett J, Brumbaugh MS, Pittman B, Frangou S, Glahn DC: Trait impulsivity as an endophenotype for bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord 14:565–570, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby JL, Navsaria N: Pediatric bipolar disorder: Evidence for prodromal states and early markers. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51:459–471, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft MJ, Lamy M, DelBello MP, McNamara RK, Strawn JR: Antidepressant-induced activation in children and adolescents: Risk, recognition and management. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 48:50–62, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DJ, Smith DJ: Is there a clinical prodrome of bipolar disorder? A review of the evidence. Expert Rev Neurother 13:89–98, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre RS, Correll C: Predicting and preventing bipolar disorder: The need to fundamentally advance the strategic approach. Bipolar Disord 16:451–454, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendlowicz MV, Jean-Louis G, Kelsoe JR, Akiskal HS: A comparison of recovered bipolar patients, healthy relatives of bipolar probands, and normal controls using the short TEMPS-A. J Affect Disord 85:147–151, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, Kessler RC, Lee S, Sampson NA, Viana MC, Andrade LH, Hu C, Karam EG, Ladea M, Medina-Mora ME, Ono Y, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Wells JE, Zarkov Z: Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68:241–251, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesman E, Birmaher BB, Goldstein BI, Goldstein T, Derks EM, Vleeschouwer M, Hickey MB, Axelson D, Monk K, Diler R, Hafeman D, Sakolsky DJ, Reichart CG, Wals M, Verhulst FC, Nolen WA, Hillegers MH: Categorical and dimensional psychopathology in Dutch and US offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: A preliminary cross-national comparison. J Affect Disord 205:95–102, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesman E, Nolen WA, Keijsers L, Hillegers MHJ: Baseline dimensional psychopathology and future mood disorder onset: Findings from the Dutch Bipolar Offspring Study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 136:201–209, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesman E, Nolen WA, Reichart CG, Wals M, Hillegers MH: The Dutch bipolar offspring study: 12-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 170:542–549, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Schneck CD, Singh MK, Taylor DO, George EL, Cosgrove VE, Howe ME, Dickinson LM, Garber J, Chang KD: Early intervention for symptomatic youth at risk for bipolar disorder: A randomized trial of family-focused therapy. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52:121–131, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M: A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 134:382–389, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno C, Laje G, Blanco C, Jiang H, Schmidt AB, Olfson M: National trends in the outpatient diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in youth. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:1032–1039, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muneer A: The neurobiology of bipolar disorder: An integrated approach. Chonnam Med J 52:18–37, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noto MN, Noto C, Caribé AC, Miranda-Scippa Â, Nunes SO, Chaves AC, Amino D, Grassi-Oliveira R, Correll CU, Brietzke E: Clinical characteristics and influence of childhood trauma on the prodrome of bipolar disorder. Braz J Psychiatry 37:280–288, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan LA, Goldstein TR, Rooks BT, Hickey M, Fan JY, Merranko J, Monk K, Diler RS, Sakolsky DJ, Hafeman D, Iyengar S, Goldstein B, Kupfer DJ, Axelson DA, Brent DA, Birmaher B: The Relationship Between Stressful Life Events and Axis I Diagnoses Among Adolescent Offspring of Probands With Bipolar and Non-Bipolar Psychiatric Disorders and Healthy Controls: The Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS). J Clin Psychiatry 78:e234–e243, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parellada M, Gomez-Vallejo S, Burdeus M, Arango C: Developmental differences between Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Bull 43:1176–1189, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, Miyahara S, Marangell LB, Wisniewski SR, Ostacher M, DelBello MP, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Investigators S-B: Long-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: Data from the first 1000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD). Biol Psychiatry 55:875–881, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfennig A, Correll CU, Marx C, Rottmann-Wolf M, Meyer TD, Bauer M, Leopold K: Psychotherapeutic interventions in individuals at risk of developing bipolar disorder: A systematic review. Early Interv Psychiatry 8:3–11, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piersma HL, Boes JL: The GAF and psychiatric outcome: a descriptive report. Community Ment Health J 33:35–41, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios AC, Noto MN, Rizzo LB, Mansur R, Martins FE, Grassi-Oliveira R, Correll CU, Brietzke E: Early stages of bipolar disorder: Characterization and strategies for early intervention. Braz J Psychiatry 37:343–349, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shain BN: Collaborative role of the pediatrician in the diagnosis and management of bipolar disorder in adolescents. Pediatrics 130:e1725–e1742, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjelstad DV, Malt UF, Holte A: Symptoms and signs of the initial prodrome of bipolar disorder: A systematic review. J Affect Disord 126:1–13, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tijssen MJ, van Os J, Wittchen HU, Lieb R, Beesdo K, Mengelers R, Wichers M: Prediction of transition from common adolescent bipolar experiences to bipolar disorder: 10-year study. Br J Psychiatry 196:102–108, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres I, Sole B, Corrales M, Jiménez E, Rotger S, Serra-Pla JF, Forcada I, Richarte V, Mora E, Jacas C, Gómez N, Mur M, Colom F, Vieta E, Casas M, Martinez-Aran A, Goikolea JM, Ramos-Quiroga JA: Are patients with bipolar disorder and comorbid attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder more neurocognitively impaired? Bipolar Disord 19:637–650, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin K, Axelson D, Leibenluft E, Birmaher B: Differentiating bipolar disorder-not otherwise specified and severe mood dysregulation. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52:466–481, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Meter AR, Burke C, Kowatch RA, Findling RL, Youngstrom EA: Ten-year updated meta-analysis of the clinical characteristics of pediatric mania and hypomania. Bipolar Disord 18:19–32, 2016a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Meter AR, Burke C, Youngstrom EA, Faedda GL, Correll CU: The Bipolar Prodrome: Meta-Analysis of Symptom Prevalence Prior to Initial or Recurrent Mood Episodes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55:543–555, 2016b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AJ, Kim Y, Price JB, Kale RP, McGillivray JA, Berk M, Tye SJ: Stress, Inflammation, and Cellular Vulnerability during Early Stages of Affective Disorders: Biomarker Strategies and Opportunities for Prevention and Intervention. Front Psychiatry 5:34, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingo AP, Ghaemi SN: A systematic review of rates and diagnostic validity of comorbid adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 68:1776–1784, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen S, Stout R, Hower H, Killam MA, Weinstock LM, Topor DR, Dickstein DP, Hunt JI, Gill MK, Goldstein TR, Goldstein BI, Ryan ND, Strober M, Sala R, Axelson DA, Birmaher B, Keller MB: The influence of comorbid disorders on the episodicity of bipolar disorder in youth. Acta Psychiatr Scand 133:324–334, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA: A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 133:429–435, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]