Abstract

Despite early successes using recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors in clinical gene therapy trials, limitations remain making additional advancements a necessity. Some of the challenges include variable levels of pre-existing neutralizing antibodies and poor transduction in specific target tissues and/or diseases. In addition, readministration of an rAAV vector is in general not possible due to the immune response against the capsid. Recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors with novel capsids can be isolated in nature or developed through different directed evolution strategies. However, in most cases, the process of AAV selection is not well understood and new strategies are required to define the best parameters to develop more efficient and functional rAAV capsids. Therefore, the use of barcoding for AAV capsid libraries, which can be screened by high-throughput sequencing, provides a powerful tool to track AAV capsid evolution and potentially improve AAV capsid library screens. In this study, we examined how different parameters affect the screen of two different AAV libraries in two human cell types. We uncovered new and unexpected insights in how to maximize the likelihood of obtaining AAV variants with the desired properties. The major findings of the study are the following. (1) Inclusion of helper-virus for AAV replication can selectively propagate variants that can replicate to higher titers, but are not necessarily better at transduction. (2) Competition between AAVs with specific capsids can take place in cells that have been infected with different AAVs. (3) The use of low multiplicity of infections for infection results in more variation between screens and is not optimal at selecting the most desired capsids. (4) Using multiple rounds of selection can be counterproductive. We conclude that each of these parameters should be taken into consideration when screening AAV libraries for enhanced properties of interest.

Keywords: high-throughput sequencing, capsid evolution, AAV libraries

Introduction

Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) is one of the most promising gene therapy vectors. Favorable features of rAAV vectors include the capability to transduce both dividing and nondividing cells, the potential to establish long-term and stable transgene expression in quiescent tissues, and the fact that the majority of transduction events are episomal, thus reducing the risk of insertional mutagenesis. However, there are still limitations related to their use for gene transfer, which include pre-existing neutralizing antibodies to some adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes, inadequate performance in specific targets, and the possibility of diminishing expression over time, which can make readministration with a separate vector harboring a different capsid necessary.

To increase the repertoire of rAAV vectors with different properties that can overcome the limitations mentioned above, different strategies have been used to alter the AAV capsid. Directed evolution of the capsid coding sequences followed by selection of the libraries in vitro or in vivo has been shown to be a successful strategy to obtain new capsids with improved properties.1–3—Other strategies, such as peptide or designed ankyrin repeat protein (DAPRPin) insertion within specific sites in the capsids4,5 or ancestral AAV capsid reconstruction6–8—have also been described to yield vectors with more selective transduction properties. Our laboratory and others have successfully applied AAV library selection schemes that involved superinfection with a helper virus—human adenovirus 5 (Ad5)—to replicate AAV species between selection rounds. This approach ensures that the selected variants are fully functional. Moreover, using a replicating system for library screens in humanized animal models, such as the Fah−/−/Rag2−/−/Il2rg−/− (FRG) mouse model, has the advantage that only those variants that can transduce human cells are selected since Ad5 does not replicate in mouse cells with measurable efficiency.1 Although successful in many cases, the process of selecting novel AAV capsids from a highly diverse library is not well understood, and it is desirable to define the best parameters to robustly screen libraries to identify more efficient and functional AAV capsids. Parameters such as the multiplicity of infection (MOI) and the number of selection cycles may be very important for an optimal library screen but have not been studied carefully to date. Next-generation sequencing technologies allowing in-depth analysis of genomic material have recently gained remarkable popularity and are rapidly advancing the understanding of several aspects of genetics, diseases, and molecular biology. Therefore, the development of improved AAV capsid libraries that can be screened by high-throughput sequencing (HTS)9 is highly desirable to track and understand AAV capsid evolution, and has the potential to reduce time, cost, and provide better AAV variants.

In this project, we aimed to understand directed AAV capsid evolution in a replicating system using barcoded AAV that enables easy tracking of variant enrichment by HTS. Data obtained from four independent AAV library screens in two human cell lines show that infection with a high MOI is preferable over infection with a low MOI as it ensures a good representation of the complexity from the input library. In addition, we found that the most enriched AAV capsid variants were not necessarily the most efficient for transduction, whereas variants that transduced the target cell line with high efficiency were either lost or greatly diminished over rounds of selection. Most importantly, in this study, we were able to show that functional and efficient AAV variants can be obtained in a nonreplicating system after only one round of selection. The use of barcoded AAV libraries provides a tool to gain new insights into optimal AAV selection schemes, potentially resulting in the development of improved rAAV vectors for clinical applications.

Materials and Methods

Generation of the 18 AAV capsid pool

The method for generation of a pool consisting of a defined number of parental capsid AAVs is described in Ref.10 Briefly, capsids from 18 AAV serotypes (AAV1, AAV2, AAV3B, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV8, AAV9, AAV12, AAVporcine1, AAVporcine2, AAVbovine, AAVgoat1, AAVmouse1, AAVavian, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, and AAV-LK03) were cloned into the BC library vector. Each AAV capsid contained a unique barcode sequence. AAVs were purified by double CsCl gradient centrifugation, and titer was determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using an AAV2 REP gene-specific primer/probe set (sequences described below in the AAV Titration section).

Generation of 10 AAV capsid shuffled library

The method for generation of a complex AAV capsid library is described in Ref.10 Briefly, capsid sequences from eight AAV serotypes (AAV1, AAV2, AAV3B, AAV6, AAV8, AAV9, AAVporcine2, and AAVrh10), as well as from two shuffled variants AAV-DJ and AAV-LK03 that had been selected in previous screens,1,2 were used as parental sequences for the shuffling reactions. After shuffling and amplification, fragments were ligated into the BC library vector (described in Ref.10). AAVs were purified and tittered as described above for the generation of the 18 AAV capsid pool.

Cell culture

All cell lines were grown in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. HepG2.2.15 cells11 (kind gift from J. Glenn, Stanford University) were cultured in complete RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 2 mM glutamine. HaCaT cells12 (kind gift from A. Oro, Stanford University) were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine.

Selection of 18 AAV capsid pool on cells in the presence of replication

Cells were plated on 24-well plates with 0.5 mL of complete medium (HepG2.2.15: 1.5 × 105 cells/well, HaCaT: 0.3 × 105 cells/well). On the next day, medium was replaced and cells were infected with different MOIs of the 18 AAV capsid pool and incubated in a 37°C incubator for 5–6 h. Medium containing AAV was removed and cells washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove leftover input virus. Cells were then superinfected with human Ad5 obtained from ATCC (Cat. No. VR-5) (1 × 107 plaque-forming unit [PFU] in 0.5 mL of media/well) and incubated at 37°C. After 72 h, cells and supernatant were harvested, subjected to three freeze/thaw cycles, and incubated for 30 min at 65°C to inactivate Ad5. Cell debris were removed by centrifugation (5 min—400 g) and viral genomes were isolated from 20 μL of clarified supernatant using the MinElute Virus Spin Kit (Cat. No. 57704; Qiagen). The viral genome titer was determined by TaqMan qPCR using an REP primer/probe set (sequences described below in the AAV Titration section). For subsequent rounds of passaging, similar MOIs as for the initial infections were used.

Selection of 18 AAV capsid pool and 10 AAV capsid shuffled library on cells in the absence of replication

Selection was performed in the same manner as described above, however, Ad5 was not included in the medium after 5–6 h of incubation with AAV, and cells were cultured for 48 h at 37°C. Cells and AAVs were processed as above. HaCaT cells were also screened using a large well format (9.6 cm2), with more cells (4.0 × 105 cells/well) and a higher MOI (100,000).

rAAV production

rAAVs were usually produced in one T225 flask using a Ca3(PO4)2 transfection protocol in HEK 293T cells (Cat. No. CRL-3216; ATCC) with pAd5 helper, AAV transfer vector (scAAV-CAG-GFP; #83279; Addgene), ssAAV-CAG-GFP (gift from Edward Boyden, Cat. No. 37825; Addgene), or ssAAV-CAG-tdTomato (gift from Edward Boyden, Cat. No. 59462; Addgene) and pseudotyped with plasmids for each capsid of interest. For each T225 flask, 25 μg transfer vector, 25 μg packaging plasmid, and 25 μg pAd5 helper plasmid were used. rAAVs were purified using the AAVpro® Purification Kit (all serotypes by Takara).

AAV titration

Genomic DNA was extracted from 20 μL of the purified virus using the MinElute Virus Spin Kit (Cat. No. 57704; Qiagen), and the viral genome titer was determined by TaqMan qPCR. AAVs used in the screens were tittered for REP with the following primer/probe set: Fwd: 5′-TTC GAT CAA CTA CGC AGA CAG-3′, Rev: 5′-GTC CGT GAG TGA AGC AGA TAT T-3′, Probe: 5′/FAM/TCT GAT GCT GTT TCC CTG CAG ACA/BHQ-1/-3′. rAAVs containing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgene cassette were tittered for GFP with the following primer/probe set: Fwd: 5′-GAC GTA AAC GGC CAC AAG TT-3′, Rev: 5′-GAA CTT CAG GGT CAG CTT GC-3′, Probe: 5′/FAM/CGA GGG CGA TGC CAC CTA CG/BHQ-1/-3′. AAVs containing the ssCAG-GFP transgene cassette were tittered for CAG with the following primer/probe set: Fwd: 5′-GTT ACT CCC ACA GGT GAG C-3′, Rev: 5′-AGA AAC AAG CCG TCA TTA AAC C-3′, Probe: 5′/FAM/CTT CTC CTC CGG GCT GTA ATT AGC/BHQ-1/-3′.

Deep-sequencing analysis of barcoded AAV

Barcode sequences were amplified with indexed primers (F: 5′-AAT GAT ACG GCG ACC ACC GAG ATC TAC ACT CTT TCC CTA CAC GAC GCT CTT CCG ATC T (I) CGC GCC ACT AGT AAT AAA C-3′ and R: 5′-CAA GCA GAA GAC GGC ATA CGA GAT CGG TCT CGG CAT TCC TGC TGA ACC GCT CTT CCG ATC T (I) TAG AGC AAC TAG AGT TCG-3′, with the indices (I) containing between four and six nucleotides), gel-purified from 2% SYBR Safe (ThermoFisher Scientific) containing agarose gels, pooled (up to 30 samples), and sequenced on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina platform). The number of PCR cycles was minimized to avoid amplification bias and was dependent on the concentration of input AAV genomes as determined by REP qPCR. The following cycling conditions were used: 2 min 98°C, 15–35 cycles of 15 s 98°C, 15 s 50°C, 20 s 72°C, with a final 15-min extension at 72°C. High-fidelity Phusion Hot Start Flex (NEB) was used for all amplifications.

Bioinformatic analysis of barcoded AAV

The diversity of BCs was analyzed on randomly selected reads (∼400,000) after collapsing together the similar reads with five mismatches allowed (to account for sequencing errors).

Recovery and sequence contribution analysis of most prevalent AAV capsids

Capsid sequences were amplified from viral genomes after one round of selection using primer capF (5′-TGG ATG ACT GCA TCT TTG AA-3′) and a reverse primer containing the respective BC specific sequence on its 3′ end. The right BC was chosen to be included in the primer sequences so that the left BC served as a control of specific amplification of the desired variant (Fig. 1A). High-fidelity Phusion Hot Start Flex (NEB) was used for the amplifications. The number of PCR cycles was adjusted according to viral titer and frequency of the specific variant in the viral pool. The following amplification parameters were used: 2 min 98°C, 30–40 cycles of 15 s 98°C, 15 min 62°C, 2.3 min 72°C, with a final 15-min extension at 72°C. PCR products were gel purified, cloned using a Zero Blunt TOPO Kit, and Sanger sequenced. The resultant contigs were assembled using Sequencher software (v5.3) and aligned using the Muscle multiple sequence alignment software ( version 14.5.3; MacVector). The capsid sequences that matched the consensus sequence were used to generate the parental fragment, and the crossover map was generated using the Xover 3.0 DNA/protein shuffling pattern analysis software.13 Selected capsids were cloned into an AAV2 REP containing packaging vector using PacI and AscI restriction sites and used to package a self-complementary rAAV vector expressing GFP under the control of a CAG promoter (scAAV-CAG-GFP). The capsid genes cloned into the AAV vectors were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

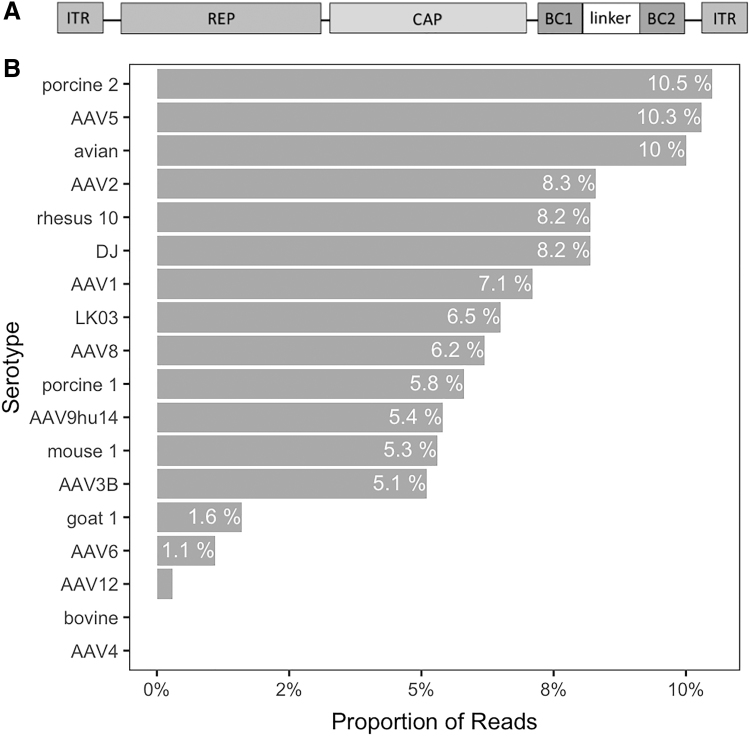

Figure 1.

Features of the 18 parental capsid pool. (A) Scheme of the AAV vectors containing the 18 different AAV capsids attached to unique barcode sequences. Each barcode contains 12 unique nucleotides and are separated by a 20 nucleotide linker (BC1-linker-BC2). The same cloning scheme was used to build the 10 parental capsid library, where the shuffled capsid sequences were cloned downstream of REP followed by unique barcode sequences. (B) Starting proportion of each BC/capsid in the 18 AAV capsid pool determined by high-throughput sequencing of barcodes (adapted from Pekrun et al.10). AAV, adeno-associated virus.

Evaluation of the transduction efficiency of different AAV vectors in HepG2.2.15 and HaCaT cells

HepG2.2.15 and HaCaT cells were transduced with different rAAV preparations containing the scAAV-CAG-GFP vector. Briefly, cells were seeded 1 day before transduction on 24-well plates so that they were about 60–70% confluent at the time of transduction (HepG2.2.15 cells: 1.5 × 105 cells/well; HaCaT cells: 0.5 × 105 cells/well). In the following day, cells were counted and AAV preparations were added to the media at different MOIs. After 48 h of transduction, cells were trypsinized and the transduction efficiencies were evaluated by flow cytometry analysis using the BD FACS Calibur instrument. The FlowJo software (version 10) was used to analyze and graph the data.

AAV competition analysis in HepG2.2.15 and HaCaT cells

For this experiment, rAAV preparations containing the ssAAV-CAG-GFP vector and the ssAAV-CAG-Tomato vector were generated. These vectors are identical apart from the fluorescent reporters (GFP or Tomato). AAVs were purified using Takara columns and titer assessed by qPCR with the primer/probe sets for the CAG region (sequences described above in the AAV Titration section). Briefly, cells were seeded 1 day before transduction on 24-well plates so that they were about 60–70% confluent at the time of transduction (HepG2.2.15 cells: 1.5 × 105 cells/well; HaCaT cells: 0.5 × 105 cells/well). In the following day, cells were counted and AAV preparations were added to the media using a total MOI of 5,000 with the AAVs mixed using different ratios (1:0, 1:1, 1:10, 1:100, and 1:1,000). After 5–6 h of transduction, the medium containing AAV was removed and cells washed twice with PBS to remove input virus and fresh media added (as it was performed for the 18 AAV capsid pool analysis). After 42–43 h of incubation, cells were trypsinized and the transduction efficiencies were evaluated by flow cytometry analysis using the BD LSR II instrument. The FlowJo software (version 10) was used to analyze and graph the data.

Results

To investigate how different strategies for screening of AAV libraries affect the selection of capsids with optimal transduction properties, we generated a defined AAV capsid pool containing AAVs with 18 different capsid sequences (AAV1, AAV2, AAV3B, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV8, AAV9, AAV12, AAVporcine1, AAVporcine2, AAVbovine, AAVgoat1, AAVmouse1, AAVavian, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, and AAV-LK03). Each capsid was linked to a unique DNA barcode sequence (made of two unique barcodes separated by a linker sequence) on the 3′ end enabling analysis by HTS (Fig. 1A).10 This 18 AAV capsid pool was used for initial studies as it has a low complexity and thus represents a powerful tool to optimize AAV library screens. The starting proportion of each of the barcodes is represented in Fig. 1B. Even though identical amounts of each AAV serotype were added to the AAV pool (based on viral genome titers), we found some variation in capsid concentrations from the expected 5.5% for each, determined by sequencing. The most remarkable variations correspond to AAV4, AAVbovine, AAV6, and AAVgoat1, which were underrepresented in the pool, and AAVporcine2, AAV5, and AAVavian, which were overrepresented in the pool. We used two different human cell lines for screen optimization: HepG2.2.15, a hepatoma cell line,11 and HaCaT, a spontaneously transformed human epithelial cell line, from adult skin.12

AAV replication is inversely correlated to the input MOI

To analyze how different amounts of virus input impact AAV replication, we used five different MOIs of the 18 AAV capsid pool for infection while maintaining the Ad5 helper virus amount constant at 1 × 107 PFU. Figure 2A shows that the higher the MOI, the lower the increase in AAV genomes in both cell lines.

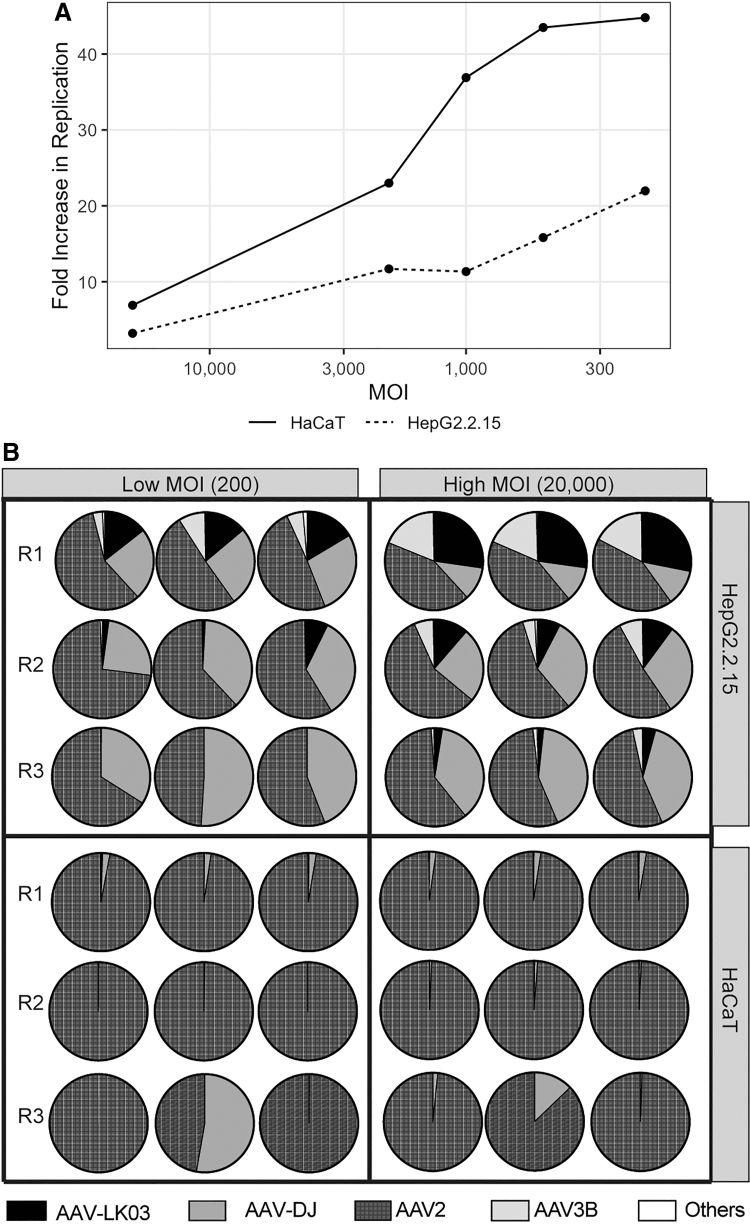

Figure 2.

AAV transduction in HepG2.2.15 and HaCaT cells. (A) Lower MOIs induce higher levels of AAV replication in HepG2.2.15 and HaCaT cells. Five different MOIs were analyzed in both cell lines. Fold increase in replication was calculated in relation to the number of input AAV by qPCR. (B) High MOI produces more consistent results among triplicates. Analysis was conducted in triplicate in HepG2.2.15 and HaCaT cell for three rounds of selection (R1, R2, and R3). Two MOIs were used (200 and 20,000) and screening was performed in the presence of a helper virus (Ad5). MOI, multiplicity of infection; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Infection with a high MOI results in a more consistent selection outcome than infection with a lower MOI

To understand how varying the MOIs affects AAV capsid diversity at each round of selection, cells were infected in triplicate with the 18 AAV capsid pool at a low MOI (200) and a high MOI (20,000) throughout three rounds of selection. In HepG2.2.15 cells, infection with a high MOI resulted in remarkable similarity among the replicates with four AAV variants (AAV-LK03, AAV3B, AAV2, and AAV-DJ) enriched over all three rounds of selection (Fig. 2B, upper right panel). In contrast, infection with a low MOI resulted in two of those AAVs (AAV-LK03 and AAV3B) being eliminated completely by round 3 (Fig. 2B, upper left panel). Moreover, reproducibility among replicates was lower in the low MOI group compared with the high MOI group. Interestingly, at both MOIs, the relative abundance of AAV-LK03 and AAV3B decreased compared with AAV2 and AAV-DJ, likely indicating a strong selective advantage of AAV2 and AAV-DJ capsid in this cell line (Fig. 2B, upper panel). Next, we tested if the same observations could be replicated using HaCaT cells infected in a similar manner with the 18 AAV capsid pool, and diversity of AAV variants was tracked at each selection round. Similar to the results obtained with HepG2.2.15 cells, a high MOI provided more consistent results than infection with a low MOI (Fig. 2B, lower panel). However, in this cell line, AAV2 was the predominant variant, corresponding to more than 97% of the AAV capsids present after the first round of selection, and more than 99% at rounds 2 and 3, regardless of the MOI used. This result indicates a strong selective advantage of AAV2 capsid in HaCaT cells.

A high efficiency of replication does not necessarily correlate with high efficiency of transduction

As mentioned above, in many of the published AAV library screens that induce replication of AAV with a helper virus, only those capsid variants enriched at later rounds of selection (passage 3 to 6) are usually vectorized and further evaluated for transduction efficiency. The reasoning is that the enriched variants selected after several rounds of selection would be the most efficient for transduction as their propagation requires completing all the steps in the AAV life cycle several times.

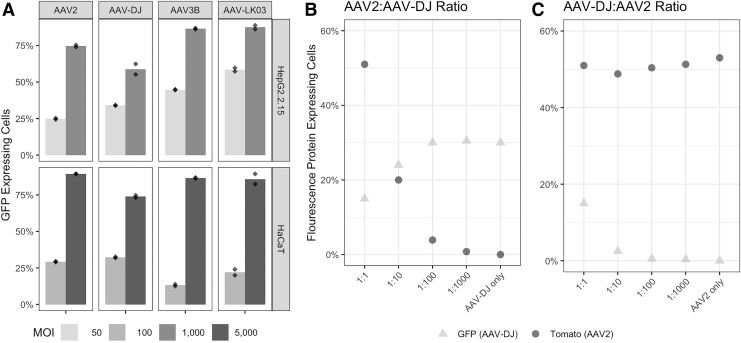

To evaluate the correlation between AAV enrichment and transduction efficiency, we packaged a GFP expressing cassette into those capsids that were the most prevalent after three rounds of selection (AAV2 and AAV-DJ in HepG2.2.15 and AAV2 in HaCaT cells). Capsid sequences from AAV-LK03 and AAV3B, which were diminished during later rounds of passaging on HepG2.2.15 cells, were also included. Unexpectedly, flow cytometry analysis revealed that AAV-LK03 and AAV3B transduced HepG2.215 cells with similar or higher efficiency than the most prevalent variants isolated at round 3 (AAV2 and AAV-DJ) (Fig. 3A, upper panel). In addition, HaCaT cells were transduced with high efficiency by all four AAV serotypes even though AAV2 was the predominant variant when performing multiple rounds of selection of the 18 AAV capsid pool (Fig. 3A, lower panel).

Figure 3.

(A) Analysis of the most and least prevalent AAV serotypes from rounds 1–3 of selection in HepG2.2.15 and HaCaT cells. Cells were transduced in duplicate with two different MOIs (50 and 1,000 for HepG2.2.15 cells and 100 and 5,000 for HaCaT cells) and analyzed by flow cytometry analysis after 48 h. Dots represent each replicate. (B) and (C) AAV2 competes with AAV-DJ for transduction in HaCaT cells. HaCaT cells were transduced with different combinations of both AAV2 (Tomato) and AAV-DJ (GFP) and analyzed by flow cytometry after 48 h. (B) Increasing amounts of AAV-DJ were mixed with AAV2 (left to right). GFP signal increases and Tomato signal decreases with increasing amounts of AAV-DJ. (C) Increasing amounts of AAV2 were mixed with AAV-DJ (left to right). The signals of GFP and Tomato are less affected, indicating less competition.

Competition between serotypes

As it was shown above, HaCaT cells were transduced mostly by AAV2 (>96%) when the 18 AAV capsid pool was used. However, when transduced individually with three other AAV serotypes, all four serotypes were capable of efficient transduction. To evaluate if this result was a consequence of a high selectivity of the cells for this serotype or an artifact due to a potential competition among the pool of AAV variants, we performed a competition experiment. AAV2 and AAV-DJ expressing GFP and Tomato-Red, respectively, were used to transduce HaCaT cells at varying vector ratios. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that AAV2 interferes with transduction of AAV-DJ (Fig. 3B). When using only one rAAV capsid for transduction at a constant MOI, AAV-DJ transduced ∼30% of the cells (Fig. 3B), while AAV2 transduced 50% (Fig. 3C). However, when both rAAVs were mixed at a 1:1 ratio, the percentage of cells transduced with AAV-DJ decreased to ∼12%, while AAV2 transduction was not affected. After using 100- and 1,000-fold less AAV2 in the mix, AAV-DJ was again able to transduce 30% of the cells, similar to the transduction efficiency obtained when omitting AAV2 (Fig. 3B). On the contrary, when we reversed the ratios of AAV2 and AAV-DJ for transduction, we did not observe interference (Fig. 3C). Even though this analysis was performed against AAV-DJ only, we believe the same competition may have occurred between AAV-LK03 and AAV3B, based on the data shown in Fig. 2B, lower panel. Moreover, we did not see any evidence of competition when the same analysis was performed in HepG2.2.15 cells (data not shown).

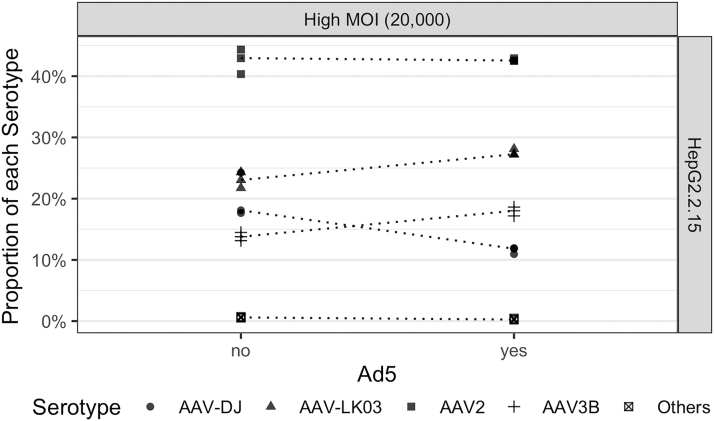

Enrichment of the same AAV variants in a nonreplicating selection scheme compared with selection in the presence of a helper virus

The variants, which were present at round 1 of selection when using a replicating system, were functional and efficient at transducing the cells they were selected on and, in some cases, even better than the variants dominating the pool at later rounds of selection (such as AAV2 and AAV-DJ in HepG2.2.15 cells) (Fig. 3A). Therefore, it is possible that in some scenarios, consecutive rounds of selection in a replicating system may be counterproductive as replication may introduce bias. To examine if the same AAV variants would be enriched after one round of AAV selection in the absence of replication, HepG2.2.15 cells were transduced solely with the 18 AAV capsid pool at a high MOI (20,000). The composition of the AAV pool resembled that found after the first round of selection in the presence of Ad5, only with AAV-DJ and AAV3B switching positions (Fig. 4). Similarly, when the same analysis was performed in HaCaT cells, AAV2 was again the most prevalent capsid, corresponding to more than 96% of all of the capsid variants (data not shown). These results show that the diversity of the AAV pool was maintained without using replication in the selection process. Although the results above suggested that a one round screen without Ad5 coinfection may be suitable for identifying AAV variants with the desired transduction properties, the 18 AAV capsid pool used in these experiments has a very low complexity. Thus, the results may not be transferable to a library screen where the pool of AAV variants is much larger. Therefore, we decided to repeat the experiment described above with a complex AAV capsid shuffled library. This library has a complexity of ∼5 × 106 variants and was generated by subjecting 10 different AAV capsid sequences to DNA shuffling (AAV1, AAV2, AAV3B, AAV6, AAV8, AAV9, AAVporcine2, AAVrh10, AAV-DJ, and AAV-LK03).10 Each shuffled AAV capsid contained a unique BC at the 3′ end of the viral sequence, similar to the scheme presented in Fig. 1A. The library was characterized using both next-generation barcode sequencing and PacBio single-molecule long-read sequencing technology. This library contained well-shuffled capsids with representation of all 10 parental sequences throughout the capsid, and each contained a unique barcode.10

Figure 4.

Transduction of HepG2.2.15 cells with and without replication (Ad5) maintained AAV diversity when using a high MOI (20,000). Experiment was performed in triplicate and samples analyzed after 72 h of transduction. Dots represent each replicate. Dotted lines indicates the same serotype.

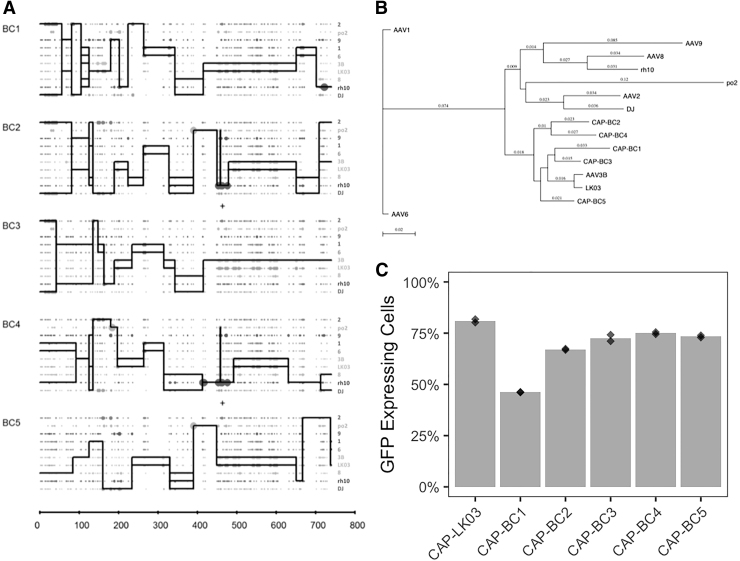

We initially infected HepG2.2.15 cells with the AAV capsid library using a high MOI (10,000) and omitting any helper virus. After 72 h, the barcoded AAVs were harvested from the cells, quantified by qPCR, and analyzed by HTS. The average total vector genome copy number obtained from the triplicates was 6.5 × 106 (6.41 × 106, 7.23 × 106, and 5.90 × 106). We determined the five most prevalent BC sequences from each of the triplicates (ranging from 0.04% to 0.09% of all BC sequences) and isolated the corresponding capsid sequences for further analysis (named AAV-CAP-BC1, CAP-BC2, CAP-BC3, CAP-BC4, and CAP-BC5). To rescue the CAP sequence from a highly diverse pool, primers specific for the 12 nucleotide sequence of the 3′ BC (BC2) were designed and used in association with a primer specific for a sequence at the 3′ part of the REP gene. Importantly, since the barcodes are composed of two different sets of 12 nucleotides BCs (Fig. 1A), after amplification and sequencing, the 5′ BC sequence (BC1), which sequence is known from the HTS analysis, served as a control to guarantee that the desired capsid sequence was correctly amplified. We cloned and sequenced each of the five most prevalent capsids and aligned their amino acid sequence with the capsid sequences used for library generation. Figure 5A shows a crossover analysis of each of the selected capsids, which indicates approximate breakpoint junctions between different parental AAV capsids. When the amino acid sequence was compared with the 10 capsids used for generation of the library, all the five variants clustered together with AAV3B and AAV-LK03 in a phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, these two AAV serotypes were also the most efficient for the transduction of HepG2.2.15 cells, as demonstrated above (Fig. 3A). The five AAV capsid variants were used to package a GFP expressing cassette, each generating similar titers (data not shown). The transduction efficiency of these AAV capsids was analyzed in HepG2.2.15 cells and compared with the best AAV serotype detected previously (AAV-LK03). With the exception of AAV-CAP-BC1, the other four AAV variants transduced cells with similar efficiency to AAV-LK03 (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

AAV chimeric capsids selected in HepG2.2.15 cells without the use of replication. (A) Crossover analysis and (B) phylogenetic tree of the five new AAV chimeric capsids demonstrate amino acid similarities among the original serotypes present in the 10 parental AAV library. Abbreviations: 2 (AAV2), po2 (AAVporcine2), 9 (AAV9), 1 (AAV1), 6 (AAV6), 3B (AAV3B), LK03 (AAV-LK03), 8 (AAV8), rh10 (AAVrh10), and DJ (AAV-DJ). (C) Transduction analysis in HepG2.2.15 cells was performed in duplicate using the new AAV chimeric capsids and AAV-LK03 (the most efficient parental serotype for HepG2.2.15 transduction; Fig. 3A) (MOI:100). Dots represent each replicate.

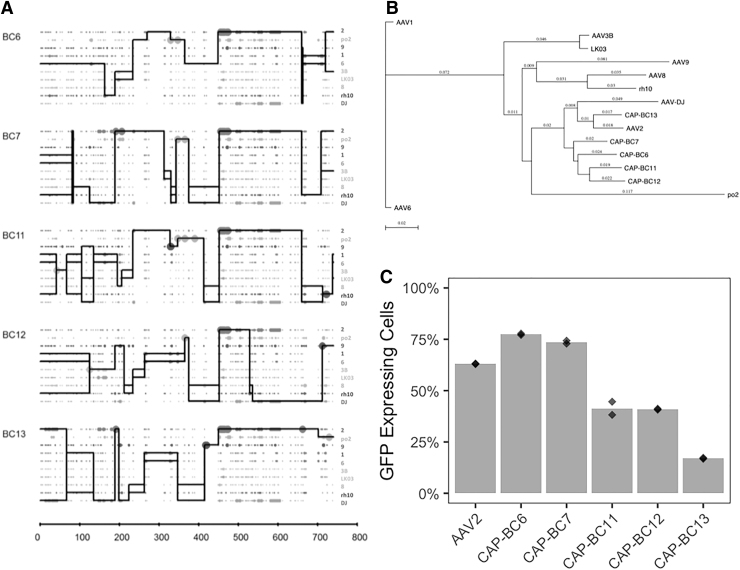

To verify the reproducibility of the results in a different cell line, a similar experiment was performed using HaCaT cells. HaCaT cells were infected with the AAV library using a high MOI (10,000) and in the absence of replication. As described in the previous experiment, the barcoded AAVs were isolated from the cells, quantified by qPCR, and analyzed by HTS. The average total vector genome copy number obtained from the triplicates was 1.1 × 105 (1.16 × 105, 4.09 × 104, and 1.86 × 105). As performed for HepG2.2.15, we selected the top five BCs for further analysis. However, we were unsuccessful in amplifying the capsids using the approach described above, most likely due to the extremely low prevalence of those sequences in the selected AAV pool. In HaCaT cells, the total number of vector genomes obtained from the cells was ∼60-fold lower than the numbers obtained in the HepG2.2.15 cells. To overcome this limitation and increase the representation of the AAV variants, we repeated the experiment using a higher number of cells for library infection as well as a 10-fold higher MOI (i.e., 100,000). Now, the average of total vector genomes obtained from the triplicates increased to 3 × 107 (1.14 × 107, 1.24 × 107, and 1.21 × 107), approximately a 300-fold increase in relation to cells transduced with a lower MOI. After performing HTS, the five most prevalent BCs were selected for further analysis (CAP-BC6, CAP-BC7, CAP-BC11, CAP-BC12, and CAP-BC13) and, owing to a sufficiently high representation in the AAV pool, were at this time successfully amplified, cloned, and sequenced.

Figure 6A shows a crossover analysis of each of the selected capsids, and their amino acid sequences were compared in a phylogenetic tree using the 10 parental capsids used for generation of the library (Fig. 6B). As it was found for the HepG2.2.15 analysis, the variants all cluster closely to the previously identified AAV serotype most efficient for the transduction of HaCaT cells (i.e., AAV2; Fig. 3A). The five AAV capsid variants were used to package a GFP expression cassette and produced similar titers of virus (data not shown). HaCaT cells were then transduced with these AAV variants as well as the best parental (AAV2). Three of the AAV variants transduced HaCaT cells with a lower efficiency than AAV2, while two variants (AAV-CAP-BC6 and AAV-CAP-BC7) transduced the cells with a slightly higher efficiency than AAV2 (77.5% CAP-BC6 and 73.6% CAP-BC7 vs. 63.1% AAV2) (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

AAV chimeric capsids selected in HaCaT cells without the use of replication. (A) Crossover analysis and (B) phylogenetic tree of the five new AAV chimeric capsids demonstrate amino acid similarities among the original serotypes present in the 10 parental AAV library. Abbreviations: 2 (AAV2), po2 (AAVporcine2), 9 (AAV9), 1 (AAV1), 6 (AAV6), 3B (AAV3B), LK03 (AAV-LK03), 8 (AAV8), rh10 (AAVrh10), and DJ (AAV-DJ). (C) Transduction analysis in HaCaT cells was performed in duplicate using the new AAV chimeric capsids and AAV2 (the most efficient parental serotype for HaCaT transduction; Fig. 3A) (MOI:100). Dots represent each replicate.

Discussion

In this work, we have uncovered some new and important findings in an AAV selection screening and highlighted the importance of using barcodes to allow a comprehensive analysis of the AAV diversity in the samples studied. Here we performed a careful analysis of the selection process that takes place during an AAV library screen. Analysis of selected variants in a high-throughput manner was facilitated by tagging each individual capsid sequence with a unique barcode. Initially we analyzed the directed molecular evolution process using a pool of only 18 different barcoded AAVs to optimize the conditions for screening of a highly diverse AAV library. This approach proved to be helpful as it enabled us to study several important parameters of a library screen, such as the effect of different MOIs on AAV replication, competition/negative dominant interference, and bias of selection caused by AAV replication.

First, we showed that infection of the target cells with a high MOI in the presence of a helper virus is beneficial as it resulted in more consistent data among replicates, whereas a low MOI resulted in more variation. These data would fit with evolution models and bottleneck mathematical models put forth by evolutionary geneticists in other types of genetic selections.14 Alternatively, this may be a consequence of more viral particles being present in the cells, which may saturate the cell replication machinery and thus the AAV numbers remain similar, and/or reduced overall replication due to physical constraints, such as limited packaging capacity of newly formed AAVs in the cells. Even though these data were obtained using an AAV pool of low complexity, using a high MOI for infection should also be beneficial when using a highly diverse AAV library if a helper virus is needed for replication. Apart from the reasons described above, this strategy would also avoid issues related to the low representation of certain variants in the cells or when highly replicative variants may overtake the AAV pool based on their increased replicative potential.

We also demonstrated that AAV variants that were enriched after several rounds of selection in the presence of replication are not necessarily the most efficient for transduction. Even though superinfection with Ad5 has the advantage of eliminating those AAVs that are defective in any of the transduction steps following cell entry, including cell trafficking, nuclear entry, and capsid uncoating, it can also introduce unwanted bias during library selection. Variants that are very efficient for replication or other aspects of the viral cycle, such as the assembly of progeny viruses, may be selected, while other variants that are best for transduction may be outcompeted and eventually eliminated from the viral pool throughout several rounds of passaging. This phenomenon was clearly demonstrated in HepG2.2.15 cells where AAV2 and AAV-DJ—which were shown to be the most prevalent variants at the latest round of selection—were less efficient than AAV-LK03 and AAV3B for transduction. Thus, when to utilize AAV helper viruses in selection screens have to be considered with other factors. More experiments will need to be performed to determine how well our results will translate to other cell types. However, for selection screens in humanized mouse models,2 human-specific helper virus-induced replication is surely beneficial as it can enrich for capsids that are specific for the human cell type because AAV will not be replicated in surrounding mouse tissues.1

Third, we uncover a mechanism of competition among different AAVs in one of the cell lines studied, where AAV2 seems to compete for transduction with at least AAV-DJ, AAV-LK03, and AAV3B. Although this may not affect the outcome of a screen when a highly complex AAV library is used (as AAV variants are very diverse and not overrepresented), the possibility of bias being introduced by this mechanism should be considered when using less diverse AAV pools. We have not elucidated the mechanism of the observed AAV competition, but it is possible that a limited distribution of capsid-specific primary or secondary receptors (such as heparan sulfate proteoglycan [HSPG], fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 [FGFR1] and hepatocyte growth factor receptor [c-Met], αVβ5 integrin, and Laminin [LamR])15–19—or the general AAV receptor,20 is the reason that competition was seen in HaCaT, but not in HepG2, cells. Thus, the AAV2 capsid might bind to such receptors present on HaCaT cells in a faster and more efficient manner than the other capsids, resulting in a transduction block for the other variants.

We believe that the most important finding of this study is the description of a new nonreplicating selection system that removed the need for multiple rounds of selection. Using this new strategy, we were not only able to overcome the potential bias introduced when superinfecting the target cells with a helper virus during library screen, but also managed to select functional capsids after only one round of selection. We showed that infection with a high MOI of the barcoded AAV library results in a sufficiently high viral copy number inside the target cell allowing in-depth sequence analysis of the selected variants and even rescue of the most enriched species by amplification with a BC-specific primer. With the protocol developed in this study, we were able to identify and isolate AAV variants that were present at levels lower than 0.04%. It is important to emphasize that MOIs may need to be optimized depending on the target cell type as well as the complexity of the library used. Different cells have markedly different permissiveness to AAV transduction as demonstrated by the low levels of transduction achieved in HaCaT cells when compared with HepG2.2.15 cells after transduction using the same MOI of AAV library. Importantly, the strategy of amplifying and Sanger sequencing the AAV capsid nucleotide sequence with a primer located in the 3′ BC (BC2) adds more robustness to the approach as the 5′ BC (BC1) (Fig. 1A) serves as an internal control to confidently link a specific BC sequence to a capsid sequence.

In conclusion, our approach of tagging each capsid variant with a unique barcode sequence enabled the analysis of very low represented AAV in a high-throughput manner, thus contributing to a deeper understanding of the process of AAV library selection in the presence of a helper virus. Moreover, the unique barcodes made it possible to isolate the desired capsid variants from highly diverse pools, even in the absence of virus replication. Here we validated our analysis using a library of shuffled AAV capsids that can be adapted with other strategies used to generate new chimeric AAV capsids.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Xuhuai Ji (Stanford Functional Genomics Facility) for performing high-throughput sequencing and Mia Jaffe and Gavin Sherlock (Stanford University) for guidance on sequencing, library generation, and discussions. We thank members of Jeffrey Glenn's and Anthony Oro's Laboratories (Stanford University) for providing us with various cell lines, and Verena Steffen for providing invaluable assistance with graphs. We also wish to thank all members of the Kay laboratory for intellectual discussions and support.

Author Disclosure

M.A.K. has commercial affiliations and stock and/or equity in companies with technology broadly related to this article. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

This project was supported by an NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant (S10-OD010580) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) with significant contribution from Stanford's Beckman Center Shared FACS facility. This work was supported by a grant to M.A.K. (NIH R01AI116698). G.D.A. was supported by a fellowship from the Child Health Research Institute of Stanford University. The funding organizations played no role in experimental design, data analysis, or article preparation.

References

- 1. Grimm D, Lee JS, Wang L, et al. In vitro and in vivo gene therapy vector evolution via multispecies interbreeding and retargeting of adeno-associated viruses. J Virol 2008;82:5887–5911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lisowski L, Dane AP, Chu K, et al. Selection and evaluation of clinically relevant AAV variants in a xenograft liver model. Nature 2014;506:382–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Paulk NK, Pekrun K, Zhu E, et al. Bioengineered AAV capsids with combined high human liver transduction in vivo and unique humoral seroreactivity. Mol Ther 2018;26:289–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Munch RC, Muth A, Muik A, et al. Off-target-free gene delivery by affinity-purified receptor-targeted viral vectors. Nat Commun 2015;6:6246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deverman BE, Pravdo PL, Simpson BP, et al. Cre-dependent selection yields AAV variants for widespread gene transfer to the adult brain. Nat Biotechnol 2016;34:204–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Santiago-Ortiz J, Ojala DS, Westesson O, et al. AAV ancestral reconstruction library enables selection of broadly infectious viral variants. Gene Ther 2015;22:934–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suzuki J, Hashimoto K, Xiao R, et al. Cochlear gene therapy with ancestral AAV in adult mice: complete transduction of inner hair cells without cochlear dysfunction. Sci Rep 2017;7:45524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Landegger LD, Pan B, Askew C, et al. A synthetic AAV vector enables safe and efficient gene transfer to the mammalian inner ear. Nat Biotechnol 2017;35:280–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adachi K, Enoki T, Kawano Y, et al. Drawing a high-resolution functional map of adeno-associated virus capsid by massively parallel sequencing. Nat Commun 2014;5:3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pekrun K, De Alencastro G, Luo QJ, et al. Using a barcoded AAV capsid library to select for clinically relevant gene therapy vectors. JCI Insight 2019;4 pii: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sells MA, Chen ML, Acs G. Production of hepatitis B virus particles in Hep G2 cells transfected with cloned hepatitis B virus DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1987;84:1005–1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boukamp P, Petrussevska RT, Breitkreutz D, et al. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J Cell Biol 1988;106:761–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang W, Johnston WA, Boden M, et al. ReX: a suite of computational tools for the design, visualization, and analysis of chimeric protein libraries. Biotechniques 2016;60:91–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levy SF, Blundell JR, Venkataram S, et al. Quantitative evolutionary dynamics using high-resolution lineage tracking. Nature 2015;519:181–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Qing K, Mah C, Hansen J, et al. Human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is a co-receptor for infection by adeno-associated virus 2. Nat Med 1999;5:71–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kashiwakura Y, Tamayose K, Iwabuchi K, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor receptor is a coreceptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. J Virol 2005;79:609–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Summerford C, Bartlett JS, Samulski RJ. AlphaVbeta5 integrin: a co-receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. Nat Med 1999;5:78–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Summerford C, Samulski RJ. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J Virol 1998;72:1438–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Akache B, Grimm D, Pandey K, et al. The 37/67-kilodalton laminin receptor is a receptor for adeno-associated virus serotypes 8, 2, 3, and 9. J Virol 2006;80:9831–9836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pillay S, Meyer NL, Puschnik AS, et al. An essential receptor for adeno-associated virus infection. Nature 2016;530:108–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]