Abstract

Children with medical technology dependency (MTD) require a medical device to compensate for a vital body function and substantial nursing care. As such, they require constant high-level supervision. Respite care provides caregivers with a temporary break, and is associated with reduced stress; however, there are often barriers. The study utilizes mixed methodology with the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN) and semistructured interviews with state-wide care coordinators to understand the gap for respite care services. Fifty-nine percent of parents who needed respite care received none. Parents of older children with MTD were more likely to report respite needs. Care coordinators described that home health shortages created barriers to respite care utilization, and the lack of respite care can lead to hospital readmission. Although respite care is a vital resource to support families of children with MTD, it is infrequently available, which can have severe consequences.

Keywords: children with medical complexity, respite care, home care, children with disabilities, caregiving

Introduction

Children with medical technology dependence (MTD) require both a medical device to compensate for the loss of a vital body function and nursing care to avert death or further disability.1–3 Conditions that cause the need for medical technology dependency include genetic, cardiac, pulmonary, and neurological etiologies; many patients are survivors of extreme prematurity.4–6 As medical advances have improved survivorship of vulnerable neonates and medically complex children, the population of children with MTD continues to increase.1,7–14 However, it is not known if the resources available to them to develop and thrive are growing in parallel. There is evidence that an increasing number of parents are losing their jobs and experiencing extreme stress due to unmet resource needs,15,16 suggesting that the growth of resources to support children with MTD is likely not keeping pace with the growth of the population itself. Because children with MTD require a high level of care and constant supervision by an awake and trained caregiver,17 it is essential that caregivers are able to access intermittent periods of substantial reprieve.

Children with MTD can live with their families (vs medical care institutions) after parental advocacy for a child with MTD who lived in a hospital for the first few years of her life led to a change to federal Medicaid policy in 1982. This change allowed Medicaid funds to be used for home care,18 and now, within eligible states, “Katie Beckett waivers” enable children with MTD to continue living in the community with medical home supports, including durable medical equipment (eg, ventilators, oxygen, and feeding pumps), home nursing services, and respite care. Respite care are services that provide caregivers with a temporary recess from caregiving.19 Respite care can be provided in both formal and informal settings. Formal respite care occurs in facilities that specialize in care for children with MTD, whereas informal care is provided in the child’s home by a trained nurse. Parents need respite care because children with medical complexity often need around the clock skilled care.17 Frequently, parents of children with MTD are providing this care in their home without a break, because they cannot access resources typically available for children (eg, daycares, babysitters, and other relatives). The constant caregiving can be exhausting, often leaving parents with increased stress levels20 and increased potential for burnout, and is associated with occurrences of child maltreatment.21 As a result, health care professionals and state funding sources have recognized the need for family supports and parental reprieve in the form of respite care.22 Respite care, in formal or informal settings, can be delivered over varying amounts of time ranging from hours to days. Typically it is considered care above that determined to be medically necessary for the child’s typical daily schedule. For example, if a child who is on a ventilator 24 hours each day is approved to receive 16 hours a day of private duty nursing, respite care would be hours in addition to the allotted 16 hours to provide parents an occasional break from their “shift.” This temporary break from caregiving tasks can give parents and caregivers a sense of freedom, stability, and support, and as a result, allow families to keep these children home and out of skilled nursing facilities.23 In addition, studies have shown that respite care is associated with reduced parental stress and improved marital quality.21

Unfortunately, there are often barriers to respite care utilization.24 Funding barriers exist because respite care is often not a required service under private insurance benefits.25 In most states, respite care is provided under Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services 1915(c) Waivers. However, because waivers are not entitlement programs, families may experience waiting lists before receiving waiver services.26 Structural barriers also exist, such as shortages of respite care facilities and limited medical transportation to and from respite care facilities. In addition, there may be sociocultural barriers to respite care use. Parents have reported hesitation to use respite services because it might signal that they are unable to cope with their child’s care.23 Research demonstrates that there is a sizeable population that needs respite care, but does not readily ask for it.27 Existing literature suggests that barriers to and perceptions of respite care vary based on parental ethnicity, with racial/ethnic minorities being less likely to report needing respite care.28

Previous studies examining respite care use have found that respite care needs are frequently unmet. However, these studies have not fully addressed the reasons behind these barriers.29 The objective of this study is to utilize mixed methodology to examine met and unmet respite care needs in order to better understand the gap in respite care service utilization for children with MTD, which may be essential to sustain community living.

Study Overview

This is a mixed methods study of the perceptions of, use of, and barriers to respite care experienced by parents for a population of children with MTD. We conducted a quantitative study using survey data from parents/guardians of children with MTD within the 2009/2010 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN) dataset.30 We also completed a qualitative study using semistructured interviews with care coordinators for a state-wide program for children requiring home health care services and technology dependence.

Quantitative

Background

The NS-CSHCN is a national survey that collects information about children with special health care needs via telephone interviews with cross-sectional waves of parents/guardians. Conducted annually since 2003, the NS-CSHCN seeks to understand the physical, emotional, and behavioral health of children with special health care needs living in the United States.31

Cohort Identification

We identified children with MTD based on survey questions about home support services and medical diagnoses. We defined children with MTD as those whose parents/guardians reported needing both home health care (“During the past 12 months/since [his/her] birth was there any time when [he/she] needed home health care”)31 and durable medical equipment (“During the past 12 months/since [his/her] birth was there any time when [he/she] needed durable medical equipment? Examples of durable medical equipment include nebulizers, blood glucose monitors, hospital beds, oxygen tanks, pressure machines, and orthotics. These are items that are not disposable”).31 Additionally, to further verify our identification of children as having a MTD, we required parent/guardian responders to have described that their child had a severe medical diagnosis from those potential diagnoses queried in the NS-CSHCN. All MTD cases must have been previously diagnosed by a health care provider as having cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, developmental disability, intellectual disability, epilepsy, a head injury (eg, concussion or traumatic brain injury), heart disorder (eg, congenital heart disease), cystic fibrosis, or Down Syndrome.

Definition of Variables

Our demographic variables included race/ethnicity, income, the respondent’s education level, child gender, child age, family structure, and insurance type.31 For the analysis, child age was dichotomized into less than 10 years of age versus 10 to 17 years. Household income was expressed as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL). The FPL was defined using the US Department of Health and Human Services Federal Poverty Guidelines. The data collected in the first half of the dataset used guidelines from 2008, and the data from the second half used guidelines from 2009. Household poverty status was determined using household income and the number of people living in the household.31 For the bivariate and multivariate analyses, family income was dichotomized into ≤200% of the FPL versus >200% of the FPL. Family structure was divided into 3 groups. A 2-parent household includes a mother (either adoptive or biological) and a father (either adoptive or biological). A single-mother household includes families with only a biological, adoptive, step, or foster mother. To preserve anonymity, “other” included all other parental structures: families with 2 mothers or 2 fathers, grandparents, aunts, uncles, unmarried partners of the parents, single fathers, families with at least 1 parent being a step-parent, or foster/legal guardian house-holds. Insurance was defined as “Public Insurance” (Medicaid, Medicare, Children’s Health Insurance Program, and Medigap coverage); “Private Insurance” (including military insurance); “Both Public and Private Insurance,” and “Other/Uninsured” (the child did not have insurance coverage at the time of the survey or at some point in the year prior to the survey, or they had a different type of insurance not covered under public or private insurance). For the analysis, due to small numbers, “other” was combined with private insurance and “uninsured” was combined with “public insurance.”

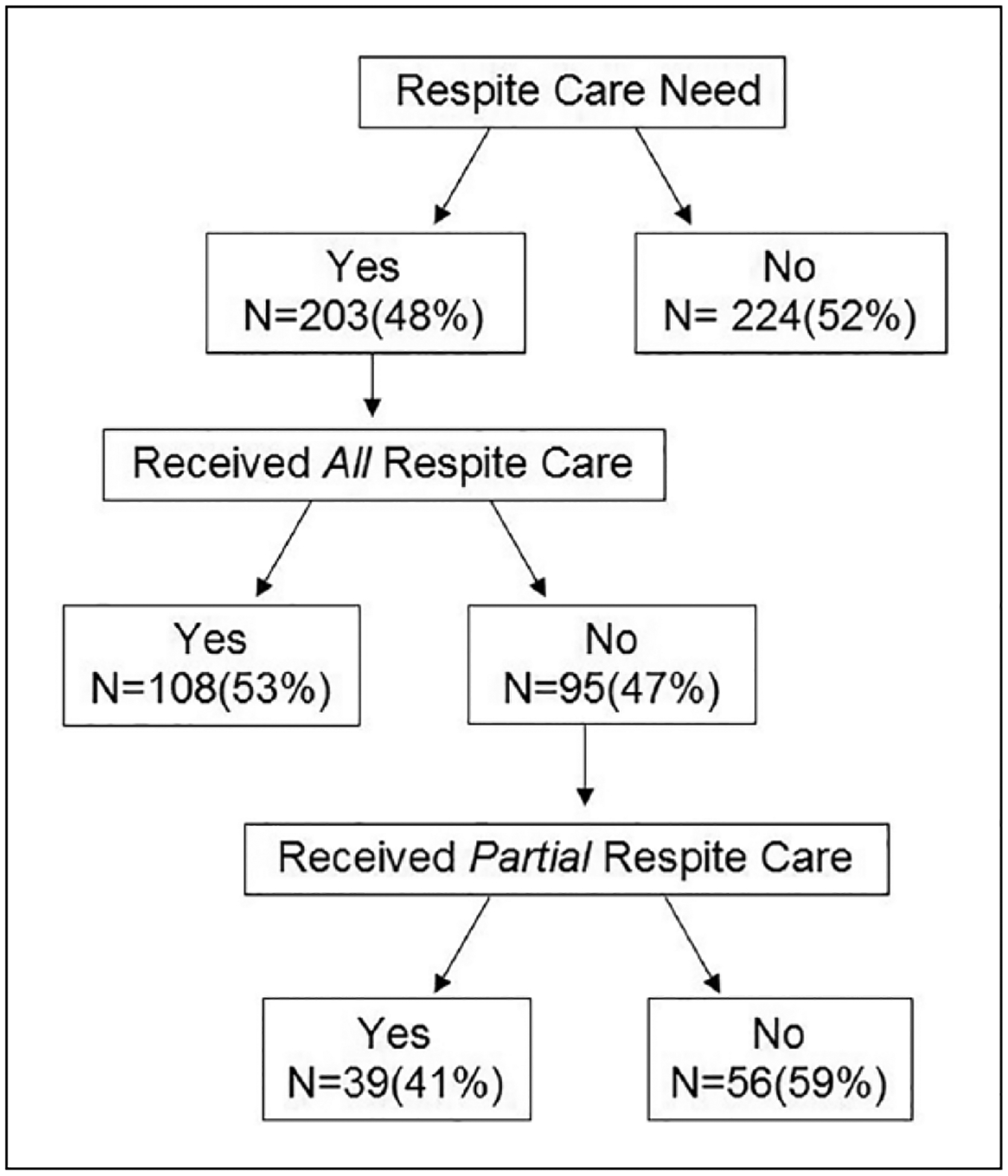

Respite care need was defined by answering affirmatively to the survey question: “During the past 12 months OR [Since [his/her] birth], was there any time when you or other family members needed respite care?” Interviewers defined respite care to families: “care for the child so the family can have a break from ongoing care of the child. Respite care can be thought of as child care or babysitting by someone trained to meet any special needs the child may have. Both professional and non-professional respite care should be included.”31 If the participants answered affirmatively, they were then asked if they received all of the respite care that they needed. Responding affirmatively indicated they received full respite care. Those who answered “no” to receiving all respite care were then asked if they received any. Responding affirmatively indicated they received “partial respite care” (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Parents of children with medical technology dependency responses to respite care questions in the National Survey for Children with Special Healthcare Needs (NS-CSHCN).

Analysis

Descriptive data analysis was completed using SAS 9.4 (SAS University Edition) and Stata/SE 14 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). For the 2 main outcome variables, respite care need and respite care receipt, associations were determined with demographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity of the child, household income, insurance type, family structure, and parent/caregiver income) and Pearson χ2 tests were computed. A full logistic regression model was built with all demographic characteristics included and presented as adjusted odds ratios in the results. NS-CSHCN population weights were not applied to the convenience sample; each respondent was treated as a single data point. Statistical significance in all analyses was defined as a 2-tailed P < .05.

Qualitative

Background

The Division of Specialized Care for Children (DSCC) was established in 1937 in Illinois as a Title V program (a Health Resources and Services Administration block grant program that funds programs to support mothers and children) to extend and improve services for children with disabilities. The DSCC Home Care Program provides care coordination services for all children in the state receiving Medicaid services for home care and has been in operation since the Department of Health and Human Services established a Medicaid waiver under Section 1915(c) of the Social Security Act allowing for technology-dependent children to be cared for at home and supported by Medicaid-funded long-term care services.32 The DSCC Home Care Program works to help support children with medical complexities and technology dependence. Care coordinators work with families to identify therapy and medical care services, fulfill transportation needs, communicate with specialists, and help families find and coordinate home care nursing and durable medical equipment.

Participant Recruitment and Study Methods

Care coordinator supervisors screened the DSCC employee roster to identify eligible participants: DSCC care coordinators who had worked with the Home Care Program for at least 1 year. Participants were contacted via email and invited to participate. A topic guide was created based on the goals of the overall study design: to understand the process of hospital-to-home discharge, essential supports for families living at home with a child with MTD (eg, respite care), and factors that influence hospital readmission for children with technology dependency. Care coordinators were asked about their educational and employment background, their experiences supporting families, their perspectives of parental experiences caring for a child with MTD, and respite care. The topic guide also asked about factors that influence child health and development, medical resources, home nursing, the hospital-to-home transition, and readmissions. Each semistructured individual interview lasted approximately 70 minutes. Interviews were audiotaped with handheld devices and field notes were captured. Data were de-identified and transcribed verbatim.

Analytic Strategy

All interviews were coded independently by 2 reviewers (SS and EL) using a modified template approach in which the interview guide served as an initial codebook, which was iteratively modified as additional themes emerged.33 Coders resolved differences by discussing to agreement to ensure intercoder reliability. The analyses presented in this article are limited to the themes relating to respite care.

Results

Quantitative

The total convenience sample of children with MTD identified in the NS-CSHCN survey was 427 with 48% of parents/guardians (N = 203) reporting needing respite care. Fifty-nine percent of these children described in the study were male, 68% non-Hispanic white, and 51% were supported by public insurance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Children With Medical Technology Dependence in NS-CSHCN 2009–2010 (N = 427).

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| <1 | 29 | 7 |

| 1–2 | 63 | 15 |

| 3–4 | 54 | 13 |

| 5–9 | 132 | 31 |

| 10–17 | 149 | 35 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 253 | 59 |

| Female | 174 | 41 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 289 | 68 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 35 | 8 |

| Hispanic | 58 | 14 |

| Other | 45 | 11 |

| Household income (% federal poverty levela) | ||

| <100 | 111 | 26 |

| 100–199 | 103 | 24 |

| 200–399 | 132 | 31 |

| ≥400 | 81 | 19 |

| Insurance type | ||

| Public insurance | 217 | 51 |

| Private insurance | 78 | 18 |

| Both public and private | 115 | 27 |

| Uninsured/other insurance | 17 | 4 |

| Family structure (N = 418)b | ||

| Two parents | 255 | 61 |

| Single mother | 104 | 25 |

| Other | 59 | 14 |

| Highest education level of primary caregiver | ||

| Less than high school | 30 | 7 |

| High school | 73 | 17 |

| More than high school | 324 | 76 |

Abbreviation: NS-CSHCN, National Survey for Children with Special Health Care Needs.

The federal poverty level was defined using the US Department of Health and Human Services Federal Poverty Guidelines. The data collected in the first half of the dataset used guidelines from 2008, and the data from the second half used guidelines from 2009. Household poverty status was determined using household income and the number of people living in the household.25

The NS-CSHCN defined a 2-parent household as those with both mother (either adoptive or biological) and a father (either adoptive or biological). Other includes all other family structures and parental relationships.

Of the 203 of families that reported needing respite care, only 53% of these (N = 108) reported receiving all of the respite services that they needed. Of the 47% (N = 95) who did not receive all of the respite care that they needed, 59% (N = 56) reported not having received any respite care at all. Of the total sample, 34% (N = 147) wanted and received at least some respite care and 66% (N = 280) received none (Figure 1).

In the bivariate analysis, younger children were associated with a lower odds of reporting needing respite (odds ratio [95% confidence interval] = 0.47 [0.31–0.70]). In addition, having private insurance as compared with public insurance was associated with a lower odds of reporting needing respite care (0.56 [0.23–0.94]; Table 2). In the adjusted models, lower caregiver education was associated with lower odds of not receiving all respite care (0.36 [0.16–0.82]) and private insurance was associated with higher odds of not receiving any respite care (2.58 [1.11–5.98]; Table 3).

Table 2.

Respite Care Need for Children With Medical Technology Dependence in the NS-CSHCN 2009–2010 (N = 427).

| Characteristic | Needed Respite, N (%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)b | |||

| <1–9 | 114 (41) | 0.47 (0.31–0.70) | 0.48 (0.31–0.74) |

| 10–17 | 89 (60) | Reference | Reference |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 124 (49) | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 79 (45) | 0.87 (0.59–1.27) | 0.79 (0.52–1.19) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 135 (47) | Reference | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic black | 20 (57) | 1.52 (0.75–3.09) | 1.79 (0.81–3.96) |

| Hispanic | 29 (50) | 1.14 (0.65–2.01) | 1.45 (0.78–2.70) |

| Other | 19 (42) | 0.83 (0.44–1.57) | 0.97 (0.49–1.91) |

| Household income (% FPL) | |||

| <200 | 93 (43) | 0.49 (0.58–1.05) | 0.69 (0.43–1.10) |

| ≥200 | 110 (52) | Reference | Reference |

| Insurance typea | |||

| Public insurance | 109(48) | Reference | Reference |

| Private insurance | 29 (34) | 0.56 (0.23–0.94) | 0.48 (0.26–0.89) |

| Both public and private | 65 (57) | 1.41 (0.90–2.21) | 1.32 (0.78–2.24) |

| Family structure (N = 418) | |||

| Two parents biological/adopted | 115 (45) | Reference | Reference |

| Single mother | 55 (53) | 1.37 (0.87–2.16) | 1.31 (0.77–2.24) |

| Other | 28 (47) | 1.10 (0.62–1.94) | 1.00 (0.53–1.88) |

| Highest education level of primary caregiver | |||

| High school degree or less | 41 (40) | 0.66 (0.42–1.04) | 0.60 (0.36–1.01) |

| More than high school education | 162 (50) | Reference | Reference |

Abbreviations: NS-CSHCN, National Survey for Children with Special Health Care Needs; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; FPL, federal poverty level.

Adjusted models include all demographic variables such as child age, child gender, child race/ethnicity, household income, insurance type, family structure, and highest caregiver education.

Indicates χ2 test with significant difference at a level P < .05.

Table 3.

Unmet Respite Care Needs for Children With Medical Technology Dependence Who Described Needing Respite Care in the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (N = 203).

| Characteristic | Did Not Receive All Respite, N (%) | Unadjusted OR of Not Receiving All Respite (95% Cl) | Adjusted ORa of Not Receiving All Respite (95% Cl) | No Respite Received, N (%) | Unadjusted OR of Not Receiving Any Respite, (95% Cl) | Adjusted ORa of Not Receiving Any Respite, (95% Cl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <1–9 | 56 (49) | 1.24 (0.71–2.16) | l.l 1 (0.60–2.06) | 32 (28) | 1.06 (0.57–1.97) | 0.75 (0.37–1.53) |

| 10–17 | 39 (44) | Reference | Reference | 24 (27) | Reference | Reference |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 61 (49) | Reference | Reference | 38 (31) | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 34 (43) | 0.78 (0.44–1.38) | 0.91 (0.50–1.67) | 18 (23) | 0.67 (0.35–1.28) | 0.77 (0.39–1.55) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 63 (47) | Reference | Reference | 33 (24) | Reference | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic black | 7(35) | 0.62 (0.23–1.64) | 0.54 (0.18–1.64) | 4(20) | 0.77 (0.24–2.48) | 1.15 (0.31–4.30) |

| Hispanic | 14 (48) | 1.07 (0.48–2.38) | 0.98 (0.40–2.48) | 10 (34) | 1.63 (0.69–3.85) | 1.86 (0.71–4.89) |

| Other | 1 1 (58) | 1.57 (0.60–4.15) | 1.44 (0.5 1 −4.06) | 9(47) | 2.78 (1.04–7.43) | 3.04 (1.05–8.81) |

| Household income (% federal poverty level) | ||||||

| <200 | 49 (53) | 1.55 (0.89–2.70) | 1.61 (0.83–3.15) | 30 (32) | 1.54 (0.83–2.86) | 1.74 (0.84–3.97) |

| ≥200 | 46 (42) | Reference | Reference | 26 (24) | Reference | Reference |

| Insurance type | ||||||

| Public insurance | 55 (50) | Reference | Reference | 29 (27) | Referenceb | Reference |

| Private insurance | 16 (55) | 1.21 (0.53 2.75) | 0.93 (0.37–2.36) | 14 (48) | 2.58 (l.l 1–5.98)* | 2.22 (0.84–5.91) |

| Both public and private | 24 (37) | 0.58 (0.31–1.08) | 0.51 (0.23–1.12) | 13 (20) | 0.69 (0.33–1.45) | 0.65 (0.26–1.66) |

| Family structure (N = 198) | ||||||

| Two parent biological/adopted | 53 (46) | Reference | Reference | 33 (29) | Reference | Reference |

| Single mother | 27 (49) | 1.13 (0.49–2.15) | 1.07 (0.46–2.49) | 18 (33) | 1.21 (0.60–2.42) | 0.86 (0.35–2.13) |

| Other | 1 3 (46) | 1.01 (0.44–2.32) | 0.86 (0.32–2.32) | 3(11) | 0.30 (0.08–1.06) | 0.26 (0.06–1.03) |

| Highest education level of primary caregiver | ||||||

| High school degree or less | 14 (34) | 0.52 (0.25–1.06) | 0.36 (0.16–0.82)* | 10 (24) | 0.81 (0.37–1.79) | 0.54 (0.21–1.39) |

| More than high school | 81 (50) | Reference | Referenceb | 46 (28) | Reference | Reference |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval, OR, odds ratio.

Adjusted models include all demographic variables: child age, child gender, child race/ethnicity, household income, insurance type, family structure, and highest caregiver education.

Indicates χ2 test with significant difference at a level P < .05.

Ninety-four respondents gave answers to the question about why they did not receive respite care. Twenty-three percent (N = 22) described the main issue being lack of availability in the area and/or transportation issues. No respondents described child refusal, child illness, inability to get appointment, or treatment as reasons for not receiving respite care. The most common response, 45% of respondents, was “other” as the main reason for not receiving respite care and no additional detail was available (Table 4).

Table 4.

Reasons Families of Children With Medical Technology Dependence Did Not Receive Respite Care in the National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs (N = 94).

| Reasons for Not Receiving Respite Care | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Not available in area/transportation problems | 22 (23) |

| Cost | 13 (14) |

| Insurance barriers | 13 (14) |

| Not convenient times/could not get appointment | 11 (12) |

| Provider did not know how to treat or provide care | 9 (10) |

| Did not know where to go for treatment | 8 (9) |

| Dissatisfaction with provider | 3 (3) |

| Treatment ongoing | 3 (3) |

| Referral barriers | 2 (2) |

| Other | 42 (45) |

Qualitative

Participant Characteristics.

Fifteen semistructured interviews were completed lasting a mean duration (range) of 77 (51–122) minutes. On average, care coordinators were 45 years old and had worked as a care coordinator for 6.6 years (Table 5). The majority of participants (93%) were women; approximately half of the respondents (52%) had a master’s degree in social work, counseling, or psychology.

Table 5.

Demographic Characteristics of DSCC Care Coordinators.

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (range) | 45.2 (28–57) |

| Female | 14 (93) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 7 (47) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 6 (40) |

| Hispanic | 2 (13) |

| Total household income | |

| 50 000–99 000 | 11 (79) |

| 100000–150000 | 3 (21) |

| Marital status | |

| Nonmarried | 4 (27) |

| Married/living as married | 11 (73) |

| Years in care coordinator role, mean (range) | 6.6 (1–27) |

| Educational background | |

| Registered nurse | 5 (33) |

| Masters in social work or counseling | 8 (52) |

| Physical therapy/occupational therapy | 2 (13) |

Abbreviation: DSCC, Division of Specialized Care for Children.

Emergent Themes.

The following themes were discovered. More detailed quotes for each theme can be found in Table 6.

Table 6.

Detailed Quotes for Respite Care Theme From Interviews With Care Coordinators for Children With Medical Technology Dependency (N = 15).

| Theme I: Care Coordinators’ Perception of Respite Care |

| I.A. It is a vital resource |

| “You need it. It’s vital.” (CC6) |

| “I think it’s wonderful. I’m pretty sure a lot of them feel guilty, but you have to take time for you. And I tell parents that all the time. Like, ‘Yes, you love your child. But you’re gonna probably be in this for 10, 15, 20, 30, years. You have to find that time to reconnect. Even if it’s once every three months, you have to find some time for yourselves. Leave the child at home with the nurse and go to the Christmas party or whatever together.’” (CC11) |

| “It’s wonderful for her. Because that’s what the respite is for. It’s for the parent … you can just take a break.” (CC6) |

| I.B. It is underutilized |

| “I think it’s underused. It’s really underused. I think the families who I have who are using it are using it more to patch in, like to make a full shift, once a week. I have a family, child, he gets the minimum resource allocation, so it doesn’t make five complete shifts. So the family is whittling away with a little bit of respite every week.” (CC2) |

| “I don’t have a lot of experience with respite care. I’ve only had maybe two cases where the family wanted to go somewhere.” (CC7) |

| “I have not had any families who have taken advantage of respite.” (CC15) |

| Theme II: Examples of Families’ Use of Respite Care |

| II.A. To go on vacation |

| “In the event that the family has a vacation or they have to do something where they’re unable to take this medically fragile child with them, they can always opt to have them go to one of these transitional facilities, so that they receive round the clock nursing services. And that’s covered through their respite.” (CC8) |

| “I have families that do it in-home. I have a mom—twice a year she goes to Jamaica, because she’s from—once a year she’ll take her son. They just went for Christmas. And one year she wants 24-hour care in-home. And so she has usually a family friend who’s trained nearby or her adult son—now he’s trained—nearby. But she has 24-hour coverage while she’s away. And she’s usually gone from four to five days. And that’s how she utilizes her respite.” (CC6) |

| “Some families, like I say, just need a break, and just need to have it, so they can have some little normalcy. Especially if it’s a couple. They may want to just have some kind of—even if it’s a single parent, just say, ‘OK, I need some rest.’” (CC9) |

| II.B. To add to nursing hours |

| “Respite care is just giving the family more hours for nursing.” (CC9) |

| “[A] lot of times, respite hours are also used when the amount of monthly hours that they were originally approved for is just not sufficient … mom and dad … still have obligations, and they still have things to do. And they have other children … and other commitments…. They need to dip into their respite hours, in order to have a nurse stay longer. Or to have another nurse come in to cover the time that mom and dad need to be away.” (CC8) |

| “A lot of families use respite care if they’re working, to add on to shifts, so the nurse can stay a little longer.” (CC9) |

| II.C. Other respite uses |

| “An illness. A parent goes into the hospital, and there’s not another trained caregiver. Emergency traveling. You know, another state or country, for a family funeral, or that kind of stuff, is what I’ve also seen it used for. (CC3) |

| “Some families use it so they can just get a break. And it’s not to say, ‘I don’t want my child.’ But just let them just breathe a little bit. They go for three days, and maybe just get a chance to sleep, rest, and let [a respite care center] have the child for three days. Maybe a weekend away.” (CC9) |

| “Some families have used respite where they may need to paint the home, and the child can’t be there.” (CC9) |

| Theme III: Barriers to Respite Care Use |

| III.A. Families cannot fill their basic nursing hours |

| “I really don’t have a lot of people using respite…. In order to use respite, you have to be using all of your regular hours … if these cases aren’t fully staffed, they can’t even use their respite.” (CC2) |

| “But mostly it’s not being used because there’s not enough nurses to even fill the hours.” (CC11) |

| “They can use respite through their waiver if they have it, if the agency has enough staffing. Sometimes they can use it. Sometimes—they are allotted 336 hours a year. Some families use it up like right away. Other families can never use it, because they never are fully staffed.”- (CC4) |

| III.B. Lack of available beds |

| “Unfortunately, sometimes it’s not always available. Sometimes the beds are not available. So those families that do decide to go on a trip and leave their child in the transitional care and the respite facilities, and they can’t, because there’s no beds available for them. I mean, things that we may plan a week ahead, they may need like four, five, six months to plan ahead.” (CC3) |

| “[The respite care center] sometimes is all booked up. They don’t have the bed space. So then these families, like they need a break. And sometimes there’s no way to give it.” (CC4) |

| “I have a family—the parents are from India … and [the respite care center] didn’t have any beds … so the family arranged with [another respite care center], to take him, and it was all set. [But] sure enough they used the bed for something else. And so what this family did instead of mom and dad going to India together, Dad went first, mom stayed home with him, and then they flip-flopped.” (CC2) |

| “During the times of the year … around holidays or vacation, we may have more families requesting stay at [respite care centers]. But unfortunately, sometimes, due to the limited number of beds available, this may not be possible. (CC10) |

| III.C. Parent hesitations |

| “Some families just are like, ‘No, it’s my child, and I can’t leave them somewhere else. And they’re exposed to god know what there.’ You know, infection, whatever.” (CC4) |

| “Or maybe their child is younger, and they can’t imagine…. If their child’s very cognitively aware, I think they’re not going to leave the child [in a respite care center].” (CC4) |

| “Some families don’t want to even think about this opportunity, even if they are totally overwhelmed … they think that when they are not in the picture for a while, then they don’t have control over what’s going on. The child may be harmed.” (CC10) |

| Theme IV: Respite-Related Readmissions |

| IV.A. Readmissions due to lack of nursing coverage |

| “Sometimes we see increased number of medical complications and even hospitalizations or ER [emergency room] visits, that possibly could have been avoided if there was better nursing support.” (CC10) |

| “If you don’t have the nursing, then the parents are up. If the parents are up, then they’re tired. If they’re tired, then mistakes can happen. Then what happens? Then the child has to go back into the hospital…. If you don’t have help, you can’t do it all. You can’t do 24/7.” (CC12) |

| “I have a mom, and she lives in southern Illinois, way down there. So that’s really hard to get nursing…. [Mom] ended up having cancer … she has to go to the hospital. And who’s going to take care of this child? Because her husband works. And then she had two other kids to take care of too, tha. So, then it was like ‘OK, we’re going to put her back in somewhere.’ So we ended up putting her back into [the hospital]—the child. OK? And so the mom got the surgeries and did all that, and she had some recuperation time and all that.” (CC12) |

| IV.B. Readmissions due to home issues |

| “If they don’t have—if power’s out, the electric company, the gas company—they get letters letting them know there is this family in your area that needs to be attended to first. But if definitely it’s not turned on, you need to head to the hospital.” (CC3) |

| “I have a family who had a mice infestation in their apartment…. The nurses—they weren’t going to work there, and nursing stopped. And then mom has three other kids. There’s a dad, but he works all the time. So it’s just her. And her three younger kids are all under four, so it’s just toddlers and everything. And eventually the child was hospitalized because it was just too much. No nursing, mice running around, just mom.” (CC14) |

General Perceptions of Respite Care

When asked to speak generally about respite care, care coordinators often described it as an essential resource for parents to have a reprieve from unrelenting caregiving. Care coordinators defined respite care as something that is needed to, “Decompress. You need it, it’s vital.” “It’s wonderful.” “Parents need some time away.” Several care coordinators mentioned trying to encourage parents when they are feeling a little overwhelmed, “Have you thought about your respite?” A theme emerged of overall underutilization of respite care, with several care coordinator describing little or no experience in her caseload: “I have not had any families who have taken advantage of respite.” “I don’t have a lot of experience with respite care … maybe 2 cases.”

Examples of Families’ Use of Respite

When speaking specifically about how families are using respite care, coordinators describe families using such services when they have to go somewhere, like a vacation, “where they cannot take [their] medically fragile child.” At times respite care use was for “emergency traveling, to another state or country for a family funeral” or for “an illness. A parent goes into the hospital, and there’s not another trained caregiver.” In a few examples, care coordinators described families using respite care when they need to have home modifications done. For example, if a family needs “to paint the home, and the child can’t be there.” Sometimes respite care was described as being used in small amounts of time to supplement daily nursing care, for example, “families use respite care if they’re working, to add on to shifts, so the nurse can stay a little longer.”

Barriers to Respite Care Use

Although care coordinators often spoke highly of respite care as a key supportive service for families, they most often described barriers to respite care use. Care coordinators frequently described that families in their caseload could not access this service: “I don’t have a lot of people using respite. Cases aren’t fully staffed, so they can’t use their respite.” One of the reasons cited for not using respite care was that “in order to use respite, you have to be using all of your regular [nursing] hours.” Respite care nursing hours are considered hours above those deemed medically necessary for the care of the child. Because the majority of families did not even receive this baseline nursing support, most could not tap into additional respite hours. Additionally, coordinators reported that even when a family had nurses who were willing to provide informal respite care, the nursing agencies would not allow the nurses to work overtime to provide this care. In some cases, “the nurses themselves like the family so much, they’re even willing to change their schedule a little bit. But the nursing agency won’t allow it.” In addition to the inability to use respite care in the home, care coordinators often articulated an inability to use formal respite care locations because beds were unavailable: “Families decide to go on a trip and leave their child in the respite facilities, and they can’t, because there’s no bed available for them.” One strategy a care coordinator advised to address this shortage, “Call now, even for [wanting respite] a month from now, so that your name is on a waiting list.”

Respite-Related Readmissions

In conversations about readmissions, care coordinators described examples of families being forced to use the hospital for emergency respite services. Most often, the reasons for these respite-related readmissions were due to lack of nursing coverage: “After a week or two without nursing support, they physically are unable to do it at the required level … they are not medical professionals.” Several others described, “We see increased medical complications, hospitalizations, and emergency room visits, which possibly could have been avoided if there was better nursing support.” “After a while, families may end up at the ER just because the nurse didn’t show up. They’re tired.” “She didn’t have nursing and she took them to the hospital. The nurse was off or sick, and the foster mom said, ‘I just can’t do this.’” Care coordinators described that at times an issue arises with the family home, and the health and safety of the child are compromised. Although this issue could potentially be addressed with respite care services, hospitalizations were the only option: “Eventually the child was hospitalized because it was just too much. No nursing, mice running around, just mom.” “They’re moving … they don’t have the backup or the support.”

Discussion

The literature suggests that while respite care is a helpful resource to families with children with medical complexity, it is often difficult to access.24,29 Our findings from a national survey and in-depth qualitative interviews verify that respite care needs are often unmet, and the reasons for this are complex and related to both system-level and patient-level barriers. Both health facilities and home health providers are limited, which severely affects respite opportunities.

In the qualitative portion of this study, care coordinators frequently reported that families’ lack of staffing, even their regular nursing hours, meant that the intermittent ability to augment these hours to provide respite was impossible. Difficulty finding home nurses to care for children with MTD is a barrier that has previously been described in the literature.34 The care coordinators described that as a result of the inability to fill regular nursing hours and provide subsequent respite care, caregivers experience increasing levels of stress without relief. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that “new and expanded funding mechanisms must be established to support respite care for families with children who have complex medical problems … Respite care for primary caregivers must be included in all pediatric home health care benefits.”35 However, Medicaid agencies often reimburse respite care at such low rates as to deter recruitment of providers.25 Increased provision of respite care services necessitates improving reimbursement to home health providers.

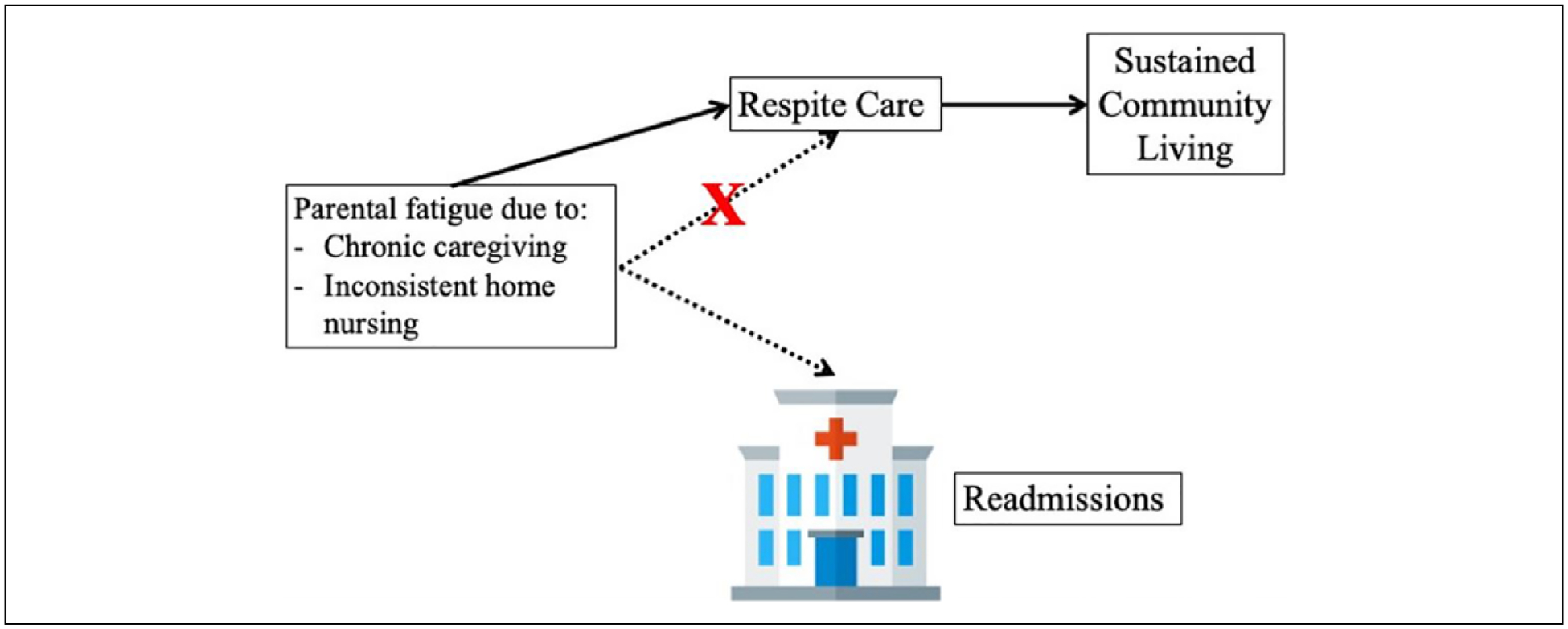

A clear theme emerged about the impact of lack of home health nurses on subsequent readmissions. At times, families return to the hospital or emergency room as a last effort to obtain help with caregiving. It is possible that more consistent caregiving, or alternatives for respite care, may have avoided these emergency hospitalizations (Figure 2). Hospital readmissions for children with ventilators are frequent and expected,36–39 and the qualitative component of this study allowed us to explore instigators of hospital readmissions in this population, which may not be captured in hospital data.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model for impact of lack of respite care on hospital admissions.

Parental negative perceptions and reservations about respite care also present significant barriers to use. Existing literature suggests that there is a considerable need for respite care that goes unmet because parents have hesitations about utilizing such services.23 In our qualitative study, care coordinators described that parents may not want to leave their child in the care of “strangers” for prolonged periods of time. This may explain the relationship between the age of the child and reported need for respite noted in our quantitative study. It is possible that parents are not comfortable leaving their younger children (vs older children) in the care of others. Alternatively, parents may be less willing to request respite services for younger children because of sociocultural norms to spend significantly more time with young children compared with older children. Earlier studies have found that as parental age increases, so too does the use of respite.40 In our analysis, we found a correlation between respite care need and child age, which also correlates with parental age. It is not clear whether aging children, or aging caregivers primarily drives this association, but may be helpful when planning for future needs of young children (and young caregiver parents) with MTD.

This study has several limitations; we begin with those of the quantitative survey. First, we defined children with MTD in the NS-CSHCN survey narrowly (in an effort to identify individuals with MTD with high specificity), and we likely excluded children who had MTD but did not fit into one of the survey’s medical diagnostic categories (eg, lower sensitivity). Second, in the NS-CSHCN, the most common reason for not receiving respite care was described as “other” and the survey’s closed response options did not allow additional detail. In our qualitative study, the generalizability of our results are limited by our small sample size and qualitative focus within the state of Illinois. Additionally, we acknowledge that while care coordinators work intimately with families, their perspectives may differ from parents. Therefore, future research should engage with parents and families as study participants to have a more comprehensive understanding of how best to provide the essential service of respite care.

Summary and Conclusion

Although respite care is a vital resource to support families with a child with MTD living in the community, there are many barriers to access. This mixed methods study, utilizing data from a national survey and qualitative data from in-depth interviews with care coordinators for a state-wide program, provides a window into the complex picture of barriers to respite care services. Primarily, the dearth of respite providers and centers makes access to respite care often impossible. Furthermore, not only does the shortage of home health providers block intermittent reprieve for families, but there was a clear theme that the lack respite provision results in otherwise avoidable readmissions to the hospital. More respite options for children with MTD are needed to support caregivers and sustain intact families living within the community.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express gratitude to the care coordinators at University of Illinois at Chicago’s Division of Specialized Care for Children (DSCC) as well as the DSCC leadership who volunteered their time to participate and support this study.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Sobotka received support from The University of Chicago Patient Centered Outcomes Research K12 Training Program (5K12HS023007) and the T73 Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental and Related Disorders Training Program (LEND).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Palfrey JS, Haynie M, Porter S, et al. Prevalence of medical technology assistance among children in Massachusetts in 1987 and 1990. Public Health Rep. 1994;109:226–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mesman GR, Kuo DZ, Carroll JL, Ward WL. The impact of technology dependence on children and their families. J Pediatr Health Care. 2013;27:451–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang KW, Barnard A. Technology-dependent children and their families: a review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45:36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallis C, Paton JY, Beaton S, Jardine E. Children on long-term ventilatory support: 10 years of progress. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:998–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gowans M, Keenan HT, Bratton SL. The population prevalence of children receiving invasive home ventilation in Utah. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King AC. Long-term home mechanical ventilation in the United States. Respir Care. 2012;57:921–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elias ER, Murphy NA; Council on Children with Disabilities. Home care of children and youth with complex health care needs and technology dependencies. Pediatrics. 2012;129:996–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benneyworth BD, Gebremariam A, Clark SJ, Shanley TP, Davis MM. Inpatient health care utilization for children dependent on long-term mechanical ventilation. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1533–e1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feudtner C, Villareale NL, Morray B, Sharp V, Hays RM, Neff JM. Technology-dependency among patients discharged from a children’s hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2005;5:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham RJ, Fleegler EW, Robinson WM. Chronic ventilator need in the community: a 2005 pediatric census of Massachusetts. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1280–e1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126:647–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127:529–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amin R, Sayal P, Syed F, Chaves A, Moraes TJ, MacLusky I. Pediatric long-term home mechanical ventilation: twenty years of follow-up from one Canadian center. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49:816–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burns KH, Casey PH, Lyle RE, Mac Bird T, Fussell JJ, Robbins JM. Increasing prevalence of medically complex children in US hospitals. Pediatrics. 2010;126:638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thyen U, Kuhlthau K, Perrin JM. Employment, child care, and mental health of mothers caring for children assisted by technology. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6 pt 1):1235–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirk S Families’ experiences of caring at home for a technology-dependent child: a review of the literature. Child Care Health Dev. 1998;24:101–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterni LM, Collaco JM, Baker CD, et al. ; ATS Pediatric Chronic Home Ventilation Workgroup. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline: pediatric chronic home invasive ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e16–e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson BH. Family-centered care: four decades of progress. Fam Syst Health. 2000;18:137–156. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitmore KE. The concept of respite care. Nurs Forum. 2017;52:180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuster PA, Merkle CJ. Caregiving stress, immune function, and health: implications for research with parents of medically fragile children. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2004;27:257–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cowen PS, Reed DA. Effects of respite care for children with developmental disabilities: evaluation of an intervention for at risk families. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19:272–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson CP, Kastner TA; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee/Section on Children With Disabilities. Helping families raise children with special health care needs at home. Pediatrics. 2005;115:507–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashworth M, Baker AH. “Time and space”: carers’ views about respite care. Health Soc Care Community. 2000;8:50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doig JL, McLennan JD, Urichuk L. “Jumping through hoops”: parents’ experiences with seeking respite care for children with special needs. Child Care Hlth Dev. 2009;35:234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simpser E, Hudak ML, Section on Home Care; Committee on Child Health Financing. Financing of pediatric home health care. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20164202.28242864 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kagan J, Edgar M. Fact sheet number 11: respite for families caring for children who are medically fragile. ARCH National Respite Network Resource Center. 2014;(11):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Exel J, de Graaf G, Brouwer W. Give me a break! Informal caregiver attitudes towards respite care. Health Policy. 2008;88:73–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gannotti ME, Kaplan LC, Handwerker WP, Groce NE. Cultural influences on health care use: differences in perceived unmet needs and expectations of providers by Latino and Euro-American parents of children with special health care needs. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nageswaran S Respite care for children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.2009/10 NS-CSHCN: Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health. 2009/10 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN) [(SPSS/SAS/Stata/CSV) Indicator Data Set]. Rockville, MD: Maternal and Child Health Bureau in collaboration with the National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bramlett MD, Blumberg SJ, Ormson AE, et al. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, 2009–2010. Vital Health Stat 1. 2014;(57):1–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duckett MJ, Guy MR. Home and community-based services waivers. Health Care Financ Rev. 2000;22:123–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Using codes and code manuals: a template organizing style of interpretation In: Doing Qualitative Research in Primary Care: Multiple Strategies. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999:163–177. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hefner JL, Tsai WC. Ventilator-dependent children and the health services system. Unmet needs and coordination of care. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10:482–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Committee on Child Health Financing; Section on Home Care, American Academy of Pediatrics. Financing of pediatric home health care. Committee on Child Health Financing, Section on Home Care, American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2006;118:834–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edwards EA, O’Toole M, Wallis C. Sending children home on tracheostomy dependent ventilation: pitfalls and outcomes. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:251–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graf JM, Montagnino BA, Hueckel R, McPherson ML. Pediatric tracheostomies: a recent experience from one academic center. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2008;9:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watters K, O’Neill M, Zhu H, Graham RJ, Hall M, Berry J. Two-year mortality, complications, and healthcare use in children with Medicaid following tracheostomy. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:2611–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berry JG, Graham DA, Graham RJ, et al. Predictors of clinical outcomes and hospital resource use of children after tracheotomy. Pediatrics. 2009;124:563–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thurgate C Respite for children with complex health needs: issues from the literature. Paediatr Nurs. 2005;17: 14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]