Abstract

Background. There is a notable lack of education on nutrition and physical activity guidelines in medical schools and postgraduate training. The purpose of this study is to assess the nutrition and exercise knowledge and personal health behaviors of physicians in the Department of Medicine at a large academic center. Methods. We conducted a survey study in the Department of Medicine at the University of Florida in 2018. The survey instrument included questions on demographics, medical comorbidities, baseline perception of health and fitness, and knowledge of nutrition concepts. The Duke Activity Status Index assessed activity/functional capacity and the validated 14-point Mediterranean Diet Survey evaluated dietary preferences. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and the χ2 test was used to perform comparisons between groups. Statistical significance was determined at P < .05. Results. Out of 331 eligible physicians, 303 (92%) participated in the study. While all respondents agreed that eating well is important for health, less than a fourth followed facets of a plant-based Mediterranean diet. Only 25% correctly identified the American Heart Association recommended number of fruit and vegetable servings per day and fewer still (20%) were aware of the recommended daily added sugar limit for adults. Forty-six percent knew the American Heart Association physical activity recommendations and 52% reported more than 3 hours of personal weekly exercise. Reported fruit and vegetable consumption correlated with perceived level of importance of nutrition as well as nutrition knowledge. Forty percent of physicians (102/253) who considered nutrition at least somewhat important reported a minimum of 2 vegetable and 3 fruit servings per day, compared with 7% (3/44) of those who considered nutrition less important (“neutral,” “not important,” or “important, but I don’t have the time to focus on it right now”; P < .0001). Conclusions. This study highlights the need for significant improvement in education of physicians about nutrition and physical activity and need for physicians to focus on good personal health behaviors, which may potentially improve with better education.

Keywords: nutrition, education, physician, medical school, physical activity, stress, meditation, health care professionals, sugar, fruits, vegetables

‘Studies show that HCPs [health care professionals] who engage in healthy behaviors are more likely to promote these behaviors and are perceived as more credible and motivating to their patients.’

Background

Declines in mortality rate for coronary heart disease (CHD) have occurred, in large part, due to advances in prevention of risk factors through pharmacotherapies and lifestyle modifications.1,2 Diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity are risk factors associated with increased CHD and mortality. Obesity and overweight rates, which contribute to many risk factors, reached 70% in the United States by 2013.3 Poor diet quality is considered the top cause of premature mortality in the United States.4 While plant-based and Mediterranean-style diets, abundant in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and seeds, seem to be effective for primary prevention of major chronic diseases,5 consumption of processed foods, high in added sodium and refined sugars, has increased.6-8 Despite recommendations for 5 to 7 daily fruit and vegetable servings, the average American only eats 0.6 cups of fruit and 0.8 cups of vegetables per day per 1000 calories consumed.9 Similarly, the new 2018 Physical Activity Guideline for Americans recommends up to 300 minutes of moderate intensity exercise performed weekly in any increment, plus muscle strengthening and balance training for older adults, including in those with chronic diseases10 and only 26% of men and 19% of women have met 2008 recommendations by the Department of Health and Human Services for aerobic and muscle strengthening exercise.10

Health care professionals (HCPs) can be powerful motivators to enhance dietary and physical activity (PA) habits of their patients. Patients perceive HCPs as respected sources of health-related information and “very credible” sources of nutrition facts.11-13 HCPs’ lifestyle advice to their patients is associated with behavior changes that can lead to decline in the incidence and progression rate of various diseases.14 However, doctors usually miss the opportunity to provide lifestyle advice to patients.15,16 In one study, 4% of cardiologists reported not discussing nutrition and 58% reported spending less than 3 minutes per visit counseling on nutrition in their physician-patient visits.17 Interestingly, in another study of female physicians, nutrition and weight loss were emphasized more where 43% of female physicians counseled their patients on nutrition and 50% counseled their patients on weight loss.18

Despite the lack of counseling of patients, HCPs and medical students, in general, feel that they are healthy.19-22 In a Canadian study from 2009, physicians felt that they were generally in good to excellent health (90%) and exercised on average for 4.7 hours per week, which averages to 56 minutes per day.23 This is significantly higher than the general public where less than 5% of Americans exercise 30 minutes or more per day.24 In another study, medical students were noted to be more commonly vegetarian. Interestingly, that eating practice declined throughout medical school.25 Proper nutrition and PA are important components of physician wellness.26 Poor nutrition can affect HCPs’ physical, emotional, and cognitive functioning27 and improving physician nutrition is associated with enhanced cognitive testing results.28 HCPs’ regular PA correlates with their career satisfaction, improved sense of well-being, increased empathy, and decreased burnout.29-32

Studies show that HCPs who engage in healthy behaviors are more likely to promote these behaviors and are perceived as more credible and motivating to their patients.33-38 HCPs with healthy habits are also more likely to counsel.39 Understanding the personal health care regimens of HCPs at a large academic center and their knowledge of optimal lifestyle practices will aid in targeting future education and help us understand the connection between education of HCPs and patient counseling.

Methods

The institutional review board at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida approved this survey study. We developed a 50-item electronic survey, using the Qualtrics web-based system (Qualtrics). The survey instrument included questions on demographics, medical comorbidities, baseline perception of personal health and fitness, and knowledge of nutrition concepts (Tables 1 and 2). The bulk of the questions came from 2 validated surveys: the 14-point Mediterranean Diet Survey40 (Table 3) and the Duke Activity Status Index (DASI)41 (Table 4), to assess dietary preferences and activity/functional capacity, respectively. There were a few knowledge-based questions and items about physician stress and happiness levels that were also included (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographics and Self-Perception.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 162 | 55 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 25-34 | 110 | 37 |

| 35-44 | 82 | 28 |

| 45-54 | 47 | 16 |

| ≥55 | 57 | 19 |

| Race/ethnic background | ||

| White | 206 | 70 |

| Black or African American | 13 | 4 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 | 0.34 |

| Asian | 50 | 17 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 17 | 0.34 |

| Other | 7 | 2 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 18 | 6 |

| Specialty | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 59 | 21 |

| Endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism | 13 | 5 |

| Gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition | 30 | 11 |

| General internal medicine | 52 | 18 |

| Hospital medicine | 40 | 14 |

| Hematology and oncology | 12 | 4 |

| Infectious diseases and global medicine | 27 | 10 |

| Nephrology, hypertension, and renal transplantation | 15 | 5 |

| Palliative care | 1 | 0.35 |

| Pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine | 24 | 9 |

| Rheumatology and clinical immunology | 9 | 3 |

| Married or having a long-term partner | 221 | 75 |

| Have children younger than 15 years | 122 | 41 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes | 13 | 4 |

| Hypertension | 48 | 16 |

| Coronary artery disease | 6 | 2 |

| Do you feel overweight or underweight? | ||

| Overweight | 149 | 50 |

| Underweight | 6 | 2 |

| Neither | 142 | 48 |

| Are you happy with the way you look and feel? | 143 | 49 |

| How knowledgeable are you about nutrition? | ||

| Very knowledgeable | 87 | 30 |

| Somewhat knowledgeable | 182 | 61 |

| Neutral | 25 | 8 |

| Not knowledgeable | 2 | 1 |

| How important is nutrition in your daily life? | ||

| Very important | 126 | 42 |

| Somewhat important | 127 | 43 |

| Neutral | 22 | 7 |

| Not important | 2 | 1 |

| Important, but I don’t have the time to focus on it right now | 20 | 7 |

| Do you feel stressed about time? | ||

| Yes, always | 122 | 41 |

| Sometimes, but I usually pace myself | 149 | 50 |

| No, I have time for what I need to do | 25 | 9 |

Table 2.

Knowledge and Behavior.

| Question | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| How many minutes of moderate physical activity per week does the American Heart Association recommend for a healthy individual? | ||

| <30 minutes | 6 | 2 |

| 30-60 minutes | 55 | 19 |

| 75 minutes | 12 | 4 |

| 90 minutes | 50 | 17 |

| 150 minutes (correct answer) | 137 | 46 |

| Not sure | 36 | 12 |

| According to the American Heart Association, what is the recommended serving for fruit and vegetables per day based on a 2000 calorie/day diet? | ||

| 1-3 servings | 55 | 19 |

| 4-5 servings | 130 | 44 |

| >5 servings (correct answer) | 74 | 25 |

| Not sure | 35 | 12 |

| What is the daily added sugar limit for men and women, respectively? | ||

| 150 calories, 100 calories (correct answer) | 59 | 20 |

| 200 calories, 150 calories | 67 | 23 |

| 300 calories, 200 calories | 20 | 7 |

| 400 calories, 300 calories | 4 | 1 |

| Not sure | 145 | 49 |

| Do you know what interval training is? | ||

| Yes | 235 | 80 |

| Has your weight changed in the past 3-5 years? | ||

| Gained <5 pounds | 72 | 24 |

| Gained 5-10 pounds | 62 | 21 |

| Gained 10-20 pounds | 38 | 13 |

| Gained > 20 pounds | 11 | 4 |

| Gained > 30 pounds | 17 | 6 |

| Lost < 5 pounds | 38 | 13 |

| Lost 5-10 pounds | 15 | 5 |

| Lost 10-20 pounds | 21 | 7 |

| Lost > 20 pounds | 6 | 2 |

| Lost > 30 pounds | 15 | 5 |

| How many minutes do you meditate/do yoga/pray/or have other avenues to destress besides scholarly activity and exercise per day? | ||

| 0 minutes, I don’t have time right now | 84 | 28 |

| <10 minutes | 98 | 33 |

| 11-20 minutes | 52 | 18 |

| 21-30 minutes | 28 | 10 |

| >30 minutes | 34 | 11 |

| How many hours per week do you exercise? | ||

| 1-2 hours | 142 | 49 |

| 3-4 hours | 90 | 31 |

| 5-7 hours | 41 | 14 |

| >7 hours | 19 | 6 |

Table 3.

Fourteen-Point Mediterranean Diet Survey.

| Question | n (yes) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Do you eat products such as milk or cheese at all? | 279 | 95 |

| Do you use olive oil as main culinary fat? | 206 | 70 |

| On a given day, do you consume ≥4 tablespoons of olive oil (including oil used for frying, salads, out-of-house meals, etc)? | 238 | 81 |

| Do you consume ≥2 vegetable servings (≥1 serving raw or as a salad) per day (1 serving = 200 g [consider dishes as half a serving]) | 200 | 68 |

| Do you consume ≥3 fruit units (including natural fruit juices) per day? | 163 | 56 |

| Do you consume ≥7 glasses of wine per week? | 29 | 10 |

| Do you consume ≥3 servings of legumes per week (1 serving = 150 g)? | 150 | 51 |

| Do you consume ≥3 servings of fish or shellfish per week (1 serving = 100-150 g of fish or 4-5 units of 200 g of shellfish)? | 227 | 77 |

| Do you consume ≥3 servings of nuts (including peanuts) per week (1 serving = 30 g)? | 180 | 62 |

| Do you prefer to eat chicken, turkey, or rabbit meat over veal, pork, hamburger, or sausage? | 215 | 74 |

| Do you consume ≥2 servings of vegetables, pasta, rice, or other dishes seasoned with sofrito (sauce made with tomato and onion, leek or garlic and simmered with olive oil) per week? | 179 | 61 |

| Do you have <1 serving of red meat, hamburger, or meat products (ham, sausage, etc) per day (1 serving = 100-150 g)? | 198 | 68 |

| Do you consume <1 serving of butter, margarine or cream per day (1 serving = 12 g)? | 211 | 72 |

| Do you consume <1 sweet or carbonated beverages per day? | ||

| <1 | 245 | 83 |

| 2 | 37 | 13 |

| 3 | 8 | 3 |

| ≥4 | 5 | 2 |

| On a weekly basis, what percentage of your diet is composed of a personally cooked meal that is plant based? | ||

| <5% | 58 | 20 |

| 6%-10% | 44 | 15 |

| 10%-30% | 73 | 25 |

| 31%-50% | 49 | 17 |

| >50% | 71 | 24 |

Table 4.

Physical Activity: Duke Activity Status Index (DASI).

| Question | n (yes) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Do you take care of yourself, that is eating, dressing, bathing, and using the toilet? | 292 | 99 |

| Are you able to walk indoors, such as around the house? | 296 | 100 |

| Are you able to walk a block or 2 on level ground? | 296 | 100 |

| Are you able to climb a flight of stairs or walk up a hill without stopping? | 289 | 98 |

| Are you able to run a short distance? | 273 | 93 |

| Are you able to do light work around the house like dusting or washing dishes? | 295 | 99 |

| Are you able to do moderate work around the house like vacuuming, sweeping floors, or carrying in the groceries? | 292 | 99 |

| Are you able to heavy work around the house like scrubbing floors or lifting or moving heavy furniture? | 275 | 95 |

| Are you able to yard work like raking leaves, weeding, or pushing a power mower? | 284 | 97 |

| Can you have sexual relations? | 289 | 98 |

| Are you able to participate in strenuous activities like swimming, single tennis, football, basketball or skiing? | 266 | 90 |

| Would you participate in interval training if freely offered or at a majorly discounted rate? | 225 | 76 |

An invitation email including the link to the anonymous electronic survey was sent through individual divisions in the Department of Medicine (DOM), followed by a reminder email through an active mailing list for the DOM. The survey was open for 2 weeks in 2018. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics according to variable type and distribution. Comparisons between groups were analyzed using the χ2 test as appropriate. Statistical significance was determined at P < .05.

Results

Out of 331 eligible physicians, 303 (92%) participated in the study. The number of responses to each survey item ranged from 282 to 297. All participants were from the DOM with a large percentage from divisions of cardiology (21%) and general internal/hospital medicine (32%; Table 1). The majority were women (55%), white (70%), and married (75%).

Dietary Knowledge and Personal Practices

Tables 2 and 3 represent results of responses to knowledge and behavior questions and the validated 14-point Mediterranean Diet survey respectively. While most participants (85%, 253/296) considered nutrition at least somewhat important in their daily life, 77% responded that less than half of their meals are home cooked and plant based (Table 3). The majority reported not consuming at least 3 fruit units per day, 3 legume servings per week, or 3 servings of fish or shellfish per week (Table 3). Sixty-eight percent reported consuming at least 2 daily vegetable servings and 41% at least 3 fruit servings per day (Table 3). Ten percent reported consumption of 7 or more glasses of wine per week (Table 3).

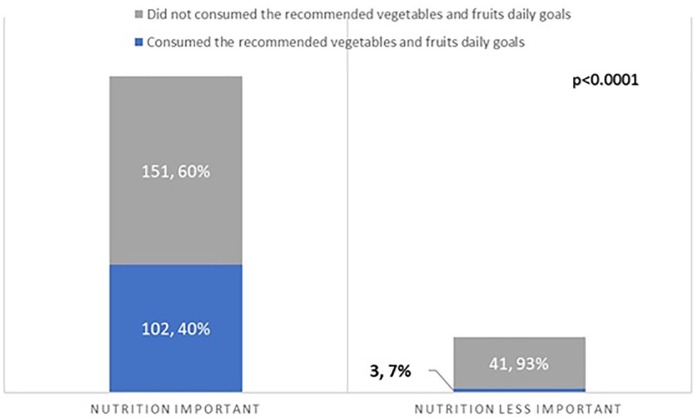

Reported fruit and vegetable consumption correlated with perceived level of importance of nutrition as well as nutrition knowledge. Forty percent of physicians (102/253) who considered nutrition at least somewhat important reported a minimum of 2 vegetable and 3 fruit servings per day, compared with 7% (3/44) of those who considered nutrition less important (“neutral,” “not important,” or “important, but I don’t have the time to focus on it right now”; P < .0001; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Perceptions of the role of nutrition and personal fruit and vegetable consumption.

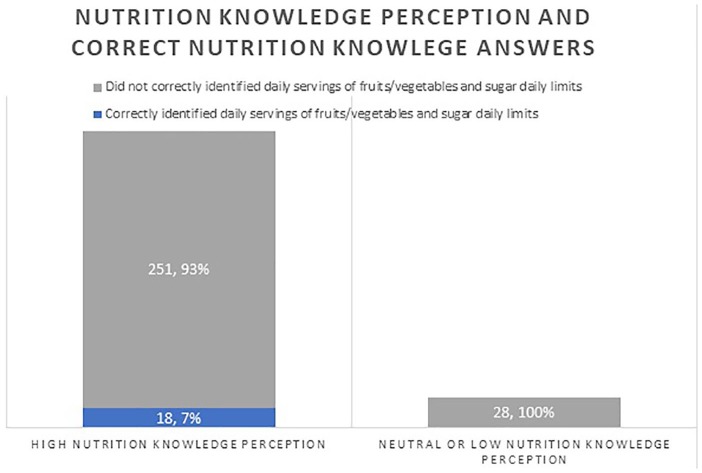

Most physicians (91%, 269/296) reported that they were somewhat or very knowledgeable about nutrition (Table 1). However, only 25% of those who felt they were knowledgeable correctly identified the recommended number of fruit and vegetable servings per day per the American Heart Association (AHA) and fewer still (20%) were aware of the recommended daily added sugar limit for men and women. Only 6% (18/297) answered both questions correctly. None of the participants that considered their nutrition knowledge neutral or not knowledgeable answered both questions correctly (P = .3932; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Health care professionals’ perception of nutrition knowledge and accuracy of knowledge-based questions.

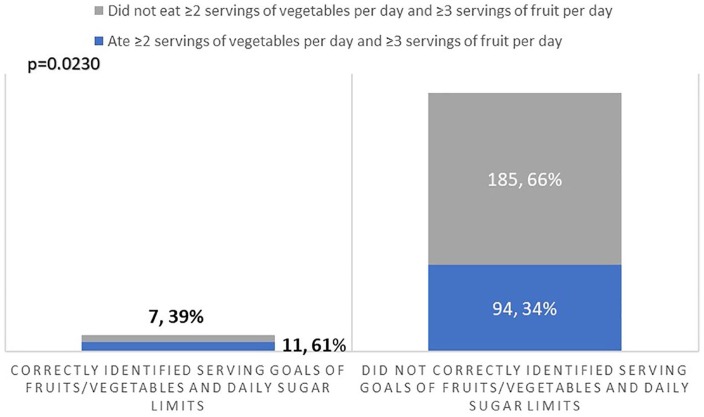

Participants who answered both nutrition knowledge questions correctly (11/18, 61%) consumed at least 2 vegetable and 3 fruit servings per day, compared with 34% (94/279) of those who did not answer both questions correctly (P = .023; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Knowledge of servings of fruits and vegetable goals and personal behavior.

Exercise Knowledge and Personal Practices

Table 4 summarizes the results of responses to the DASI. There were no significant limitations in the respondents’ ability to exercise. The majority of physicians did some level of exercise. However, only 20% of participants reported exercising ≥5 to 7 hours per week (Table 2).

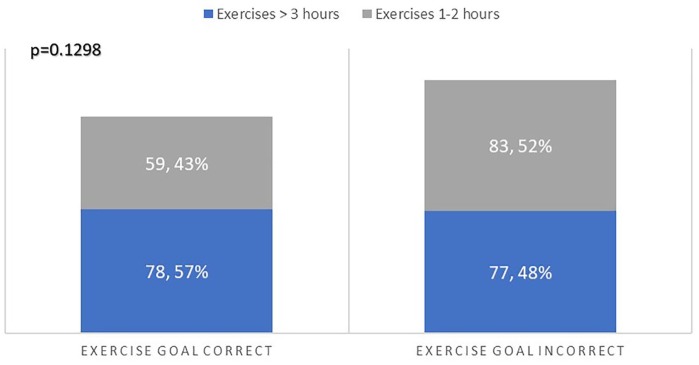

The majority (80%) reported knowing what interval training is. Forty-six percent (137/296) correctly identified the AHA recommendation for 150 minutes of moderate PA per week. Twelve percent were not sure of the AHA physical activity recommendation and the rest (42%) chose a lower target. While not statistically significant, more participants who correctly recognized the exercise goal (57%, 78/137) reported exercising over 3 hours weekly than those who did not identify the exercise goal correctly (48%, 77/160; P = .1298; Figure 4). Only 3.7% (11/296) correctly identified the recommendations for PA, fruit/vegetable servings, and calorie limit from sugar.

Figure 4.

Knowledge of exercise goals and personal behavior.

Physician Self Impression

Most participants did not have diagnosed diabetes, hypertension, or coronary artery disease (Table 1). However, 50% of participants (n = 149) reported feeling overweight. Forty-eight percent (n = 143) reported being happy with the way they looked, corresponding to 78% of participants who reported normal weight (108/139) and 22% (32/148) who reported being overweight. Ninety-one percent of participants reported some level of stress, with 41% of participants reported feeling stress most of the time. Sixty-one percent engaged in no or less than 10 minutes of activity per day to combat stress. Only 11% (n = 34) reported spending more than 30 minutes daily in activities other than scholarly ones and exercise to decrease stress, such as meditation, yoga, or praying.

Discussion

Our results show that HCPs engage in more health promoting behaviors than the general public.9,24 Our study also suggests that physicians do not reach exercise and nutrition standards set out by the AHA.20-22 Insufficient education, knowledge, and training as well as lack of time have been reported as barriers to PA counseling by physicians.42-44 Education of physicians in lifestyle tools is a significant issue where in one study, 59% of cardiologists did not recall nutrition education during their internal medicine training and more than 90% of physicians recall little or no such education in medical school.17 Other studies report infrequent and inadequate undergraduate and graduate medical education in PA.45-47 A survey of US medical schools found that only 13% of 102 schools included PA and health in the curriculum, and only 6% had a core course or requirement related to exercise.48 A review of 109 studies found that, in comparison with smoking, nutrition, alcohol, and drug use, PA was the least addressed topic in health behavior counseling curricula for medical trainees.49 The lack of knowledge of guidelines that we noted in our study, is consistent with other studies as well. A study among general practitioners in the United Kingdom, 80% of the 1013 respondents were unfamiliar with the national PA guidelines.50 Studies also suggest that the perceived relevance of nutrition education among medical students seem to decrease over their medical school training, which might suggest when initiatives need to be introduced into training.51 However, studies show that nutrition education in medical school improves counseling related confidence.52

A number of innovative strategies, both online and in the classroom, have been introduced to reduce the gap in lifestyle education and knowledge. The first nutrition and cooking elective in a medical school was offered at SUNY-Upstate in 2003. The first postgraduate course, Healthy Kitchens Healthy Lives was developed at Harvard in 2007.53 Brown University has created an elective for years 1 and 2 in the Food & Health curriculum with interactive cooking workshops. The Goldring Center for Culinary Medicine at Tulane University, a dedicated teaching kitchen that offers hands-on training with electives designed for medical students, was developed in 2013.54 The University of Florida (Gainesville, Florida) offers a nutrition in medicine course for first-year medical students, integrated nutrition content in second year medical school training and a monthly prevention conference that focuses on educating fellows on nutrition and lifestyle. Currently, 10 medical schools offer nutrition courses as electives.55 Online coursework is also available. Nutrition in Medicine (NIM) is a comprehensive online nutrition curriculum for medical students and practicing physicians, with nearly half of US medical schools utilizing components of the NIM curriculum.56

Specific physical activity education courses are less well recognized. The Healthy Living Practitioner (HLP) graduate certificate program, a 22-credit interdisciplinary curriculum trademarked by the AHA, was recently proposed to be provided in conjunction with standard training on lifestyle-based practices to supplement standard therapies. The University of Chicago implemented this program in 2017. Other international institutions, such as University of Tasmania in Australia and University of Belgrade in Serbia, are in the process of implementing the program into their curriculum. Students in all health care programs are eligible to participate in the program as an elective. Trademarking by the AHA allows for standardization of education for physicians and is an option that can be considered at organizations around the world with the potential for creating a health care environment capable of providing healthy living medicine.57 Another education source is a 10-part online course module introduced by the American College of Lifestyle Medicine designed for HCPs that focuses on the role of nutrition, sleep, exercise, and other lifestyle tools and another 10-part online module by NextGenU.org, which is an accredited Lifestyle Medicine course that is available for free and supported by many lifestyle organizations including the European Lifestyle Medicine Organization.58

One interesting finding from our study were the significant percentages of other unhealthy perception and practices. For example, 51% of respondents felt unhappy with the way they looked, 41% reported feeling stress all of the time, and 10% reported consuming more than 7 glasses of wine per week. While the vast majority of participants reported feeling stress a large percentage of time, less than half devoted at least 10 minutes per day in activities that provide avenues to relieve stress. Conversation about physician burn-out and poor physician self-care is not new and has been noted for decades.59 Our study shows that despite highlighting these issues in study, there is no trend toward improved physician personal health over time. The implementation of more widespread education of physicians on nutrition and lifestyle and a concrete focus on physician health and stress needs to be emphasized and should start at the institutional level. This has the potential effect of improving physician cognitive and emotional well-being and increasing physician counseling of patients in a “trickle-down” effect from physician wellness. Our study should serve as a “call to action” to make physician education on nutrition and lifestyle and personal well-bring a primary focus in the workplace.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that while many physicians are active and surpass the average nutrition and activity profile for people in the United States, HCPs do not reach national standards for physical activity and healthy eating. This study again highlights the need for improvement in medical education about nutrition and PA. This improvement in education will hopefully increase physicians’ focus on their own health promoting behaviors and arm physicians with tools to then provide lifestyle counseling to their patients. Physician counseling on lifestyle has a role in disease prevention/management as well as a potential role in reducing morbidity, mortality, and medical costs.60

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include the use of 2 validated surveys to assess diet and physical activity. We also had a very high response rate to the survey. Limitations include those inherent to a survey study that relies on participants’ self-report of their behavior. Previous studies, however, have shown the validity of food frequency questionnaires.61 In addition, the knowledge-based questions and stress related questions were nonvalidated questions. In addition, our study was performed at the DOM in a major academic center in southeastern United States and therefore, our results might not be generalizable to all physicians in different demographic regions. It was also noted that there were no family practice doctors included in this study and the percentage of primary care specialties was on the lower side. This survey was primarily hospital based and therefore, a larger percentage of subspecialists responded to the survey. A comparison between primary care doctors and subspecialists would be worthwhile. Future studies involving multiple specialties and various settings would be helpful to provide insight into the behavior and knowledge of physicians beyond internal medicine and in other settings, such as private practice.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was done with support from the Gatorade Foundation Education Grant and Heavener Family Foundation.

Ethical Approval: The institutional review board at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida approved this survey study.

Informed Consent: Not applicable.

Trial Registration: Not applicable.

ORCID iD: Monica Aggarwal  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7027-0060

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7027-0060

References

- 1. National Institute of Health. Conquering cardiovascular disease. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/news/2011/conquering-cardiovascular-disease. Published September 1, 2011. Accessed October 14, 2019.

- 2. Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56-e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity and overweight. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm. Accessed October 14, 2019.

- 4. The US Burden of Disease Collaborators; Mokdad AH, Ballestros K, et al. The state of US health, 1990-2016: Burden of disease, injuries, and risk factors among US states. JAMA. 2018;319:1444-1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sofi F, Cesari F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a1344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Howard BV, Wylie-Rosett J. Sugar and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the committee on nutrition of the council on nutrition, physical activity, and metabolism of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;106:523-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O’Donnell M, Mente A, Yusuf S. Sodium intake and cardiovascular health. Circ Res. 2015;116:1046-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang Q, Zhang Z, Gregg EW, Flanders WD, Merritt R, Hu FB. Added sugar intake and cardiovascular diseases mortality among US adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:516-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. US Department of Health and Human Services; US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020. 8th ed. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/. Accessed October 14, 2019.

- 10. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320:2020-2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oberg EB, Frank E. Physicians’ health practices strongly influence patient health practices. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2009;39:290-291. doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2009.422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Halm J, Amoako E. Physical activity recommendation for hypertension management: does healthcare provider advice make a difference? Ethn Dis. 2008;18:278-282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. King AC, Sallis JF, Dunn AL, et al. Overview of the Activity Counseling Trial (ACT) intervention for promoting physical activity in primary health care settings. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:1086-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2960-2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kris-Etherton PM, Akabas SR, Bales CW, et al. The need to advance nutrition education in the training of health care professionals and recommended research to evaluate implementation and effectiveness. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(5 suppl):1153S-1166S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wynn K, Trudeau JD, Taunton K, Gowans M, Scott I. Nutrition in primary care: current practices, attitudes, and barriers. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56:e109-e116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Devries S, Agatston A, Aggarwal M, et al. A deficiency of nutrition education and practice in cardiology. Am J Med. 2017;130:1298-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Frank E, Wright EH, Serdula MK, Elon LK, Baldwin G. Personal and professional nutrition-related practices of US female physicians. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:326-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frank E, Carrera JS, Elon L, Hertzberg VS. Basic demographics, health practices, and health status of US medical students. Am J Prevent Med. 2006;31:499-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Daneshvar F, Weinreich M, Daneshvar D, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness in internal medicine residents: are future physicians becoming deconditioned? J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:97-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leventer-Roberts M, Zonfrillo MR, Yu S, Dziura JD, Spiro DM. Overweight physicians during residency: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:405-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hsu DP, Hansen SL, Roberts TA, Murray CK, Mysliwiec V. Predictors of wellness behaviors in US army physicians. Mil Med. 2018;183:e641-e648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frank E, Segura C. Health practices of Canadian physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:810-8111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. US Department of Health and Human Services. Facts & statistics. https://www.hhs.gov/fitness/resource-center/facts-and-statistics/index.html. Accessed October 14, 2019.

- 25. Spencer EH, Elon LK, Frank E. Personal and professional correlates of US medical students’ vegetarianism. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:72-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamidi MS, Boggild MK, Cheung AM. Running on empty: a review of nutrition and physicians’ well-being. Postgrad Med J. 2016;92:478-481. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-134131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lemaire JB, Wallace JE, Dinsmore K, Roberts D. Food for thought: an exploratory study of how physicians experience poor workplace nutrition. Nutr J. 2011;10:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lemaire JB, Wallace JE, Dinsmore K, Lewin AM, Ghali WA, Roberts D. Physician nutrition and cognition during work hours: effect of a nutrition based intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eckleberry-Hunt J, Van Dyke A, Lick D, Tucciarone J. Changing the conversation from burnout to wellness: physician well-being in residency training programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1:225-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McClafferty H, Brown OW, Section on Integrative Medicine; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine; Section on Integrative Medicine. Physical health and wellness. Pediatrics. 2014;134:830-835. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. West CP. Physician well-being: expanding the triple aim. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:458-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taub S, Morin K, Goldrich MS, Ray P, Benjamin R. Physician health and wellness. Occup Med (Lond). 2006;56:77-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Frank E, Breyan J, Elon L. Physician disclosure of healthy personal behaviors improves credibility and ability to motivate. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:287-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Livaudais JC, Kaplan CP, Haas JS, Pérez-Stable EJ, Stewart S, Jarlais GD. Lifestyle behavior counseling for women patients among a sample of California physicians. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2005;14:485-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abramson S, Stein J, Schaufele M, Frates E, Rogan S. Personal exercise habits and counseling practices of primary care physicians: a national survey. Clin J Sport Med. 2000;10:40-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Howe M, Leidel A, Krishnan SM, Weber A, Rubenfire M, Jackson EA. Patient-related diet and exercise counseling: do providers’ own lifestyle habits matter? Prev Cardiol. 2010;13:180-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morishita Y, Numata A, Miki A, et al. Primary care physicians’ own exercise habits influence exercise counseling for patients with chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Duperly J, Lobelo F, Segura C, et al. The association between Colombian medical students’ healthy personal habits and a positive attitude toward preventive counseling: cross-sectional analyses. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Frank E, Segura C, Shen H, Oberg E. Predictors of Canadian physicians’ prevention counseling practices. Can J Public Health. 2010;101:390-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martínez-González MA, García-Arellano A, Toledo E, et al. A 14-item Mediterranean diet assessment tool and obesity indexes among high-risk subjects: the PREDIMED trial. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hlatky MA, Boineau RE, Higginbotham MB, et al. A brief self-administered questionnaire to determine functional capacity (the Duke Activity Status Index). Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:651-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hoffmann TC, Maher CG, Briffa T, et al. Prescribing exercise interventions for patients with chronic conditions. CMAJ. 2016;188:510-518. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Smith AW, Borowski LA, Liu B, et al. US primary care physicians’ diet-, physical activity–, and weight-related care of adult patients. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:33-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hebert ET, Caughy MO, Shuval K. Primary care providers’ perceptions of physical activity counselling in a clinical setting: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:625-631. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weiler R, Chew S, Coombs N, Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Physical activity education in the undergraduate curricula of all UK medical schools: are tomorrow’s doctors equipped to follow clinical guidelines? Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:1024-1026. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Solmundson K, Koehle M, McKenzie D. Are we adequately preparing the next generation of physicians to prescribe exercise as prevention and treatment? Residents express the desire for more training in exercise prescription. Can Med Educ J. 2016;7:e79-e96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wattanapisit A, Tuangratananon T, Thanamee S. Physical activity counseling in primary care and family medicine residency training: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Garry JP, Diamond JJ, Whitley TW. Physical activity curricula in medical schools. Acad Med. 2002;77:818-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hauer KE, Carney PA, Chang A, Satterfield J. Behavior change counseling curricula for medical trainees: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2012;87:956-968. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31825837be [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chatterjee R, Chapman T, Brannan MG, Varney J. GPs’ knowledge, use, and confidence in national physical activity and health guidelines and tools: a questionnaire-based survey of general practice in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67:e668-e675. doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X692513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Spencer EH, Frank E, Elon LK, Hertzberg VS, Serdula MK, Galuska DA. Predictors of nutrition counseling behaviors and attitudes in US medical students. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:655-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schlair S, Hanley K, Gillespie C, et al. How medical students’ behaviors and attitudes affect the impact of a brief curriculum on nutrition counseling. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44:653-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Eisenberg DM, Miller AM, McManus K, Burgess J, Bernstein AM. Enhancing medical education to address obesity: “See one. Taste one. Cook one. Teach one.” JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:470-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Osterweil N. Physicians and chefs cook up healthy med school curriculum. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/828443. Published July 17, 2014. Accessed October 14, 2019.

- 55. La Puma J. What is culinary medicine and what does it do? Popul Health Manag. 2016;19:1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Powell M, Zeisel SH. Nutrition in medicine. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25:471-480. doi: 10.1177/0884533610379606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lavie CJ, Laddu D, Arena R, Ortega FB, Alpert MA, Kushner RF. Healthy weight and obesity prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1506-1531. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. NextGENU.org. Home page. http://nextgenu.org/course/view.php?id=205#0. Accessed October 14, 2019.

- 59. Wells KB, Lewis CE, Leake B, Ware JE. Do physicians preach what they practice? A study of physicians’ health habits and counseling practices. JAMA. 1984;252:2846-2848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mogre V, Stevens FC, Aryee PA, Amalba A, Scherpbier AJ. Why nutrition education is inadequate in the medical curriculum: a qualitative study of students’ perspectives on barriers and strategies. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Spencer EH, Elon LK, Hertzberg VS, Stein AD, Frank E. Validation of a brief diet survey instrument among medical students. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:802-806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]