Abstract

In sub-Saharan Africa, harmful alcohol use among male drinkers is high and has deleterious consequences on adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV clinical outcomes, and couple relationship dynamics. We conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with 25 Malawian couples on ART to understand how relationships influence adherence to ART, in which alcohol use emerged as a major theme. Almost half of men (40%) reported current or past alcohol use. Although alcohol use was linked to men’s non-adherence, women buffered this harm by encouraging husbands to reduce alcohol use and by offering adherence support when men were drinking. Men’s drinking interfered with being an effective treatment guardian for wives on ART and also weakened couple support systems needed for adherence. Relationship challenges including food insecurity, intimate partner violence, and extramarital relationships appeared to exacerbate the negative consequences of alcohol use on ART adherence. In this setting, alcohol may be best understood as a couple-level issue. Alcohol interventions for people living with HIV should consider approaches that jointly engage both partners.

Keywords: Couples, Alcohol, Antiretroviral Therapy, Adherence, Sub-Saharan Africa, HIV/AIDS

Introduction

Among HIV-positive individuals, alcohol consumption is common with studies showing that rates of heavy drinking may be twice that of the general population (1). The harmful effects of alcohol use on medication adherence (2), retention in HIV care (3), viral load (4), HIV disease progression (5, 6), and survival (7) are well-documented. Non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is an important mediator between alcohol use and HIV clinical outcomes (4). HIV-positive individuals may forget to take their medication because they are intoxicated or out drinking (8) or intentionally skip pills due to “interactive toxicity beliefs” (9–12). In a meta-analysis, alcohol users were 50–60% less likely to be adherent to ART as compared to abstainers or those who drank less (2).

Although studies on HIV typically treat alcohol use as an individual-level characteristic or behavior, psychologists have long considered how alcohol use influences or is influenced by relationship dynamics at the couple level (13–16). Existing literature, mostly from the US and other developed countries, demonstrates that intimate relationships such as marriage are protective against alcohol abuse (16, 17). Other studies suggest that alcohol use can strain a relationship and fuel negative interactions between partners, leading to relationship dissatisfaction and interpersonal violence (16, 18–20). Additionally, among married couples in the US, longitudinal evidence finds that when partners differ in their drinking patterns, they are more likely to experience decreased marital satisfaction and relationship quality (15, 21).

Heavy alcohol consumption in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is a major public health concern and threat to the success of ART programs. Although the majority of individuals (60–70%) in SSA abstain from alcohol, drinkers have some of the highest rates of per capita alcohol consumption globally (22). Research in South Africa has found that alcohol consumption is independently associated with ART adherence even when accounting for structural and psychosocial factors (23), and that the event of alcohol consumption predicts a missed dose of ART (24). Alcohol consumption has been similarly associated with ART non-adherence in East and West Africa (25).

In one of the few studies examining alcohol use and couple relationship dynamics in SSA, Ugandan women reported lower relationship quality (including dyadic adjustment and sexual satisfaction) whereas men reported higher relationship quality when either partner consumed alcohol before sex (26). In South Africa, women with a hazardous-drinking male partner reported higher levels of intimacy compared to women with abstaining partners, but significantly more maladaptive communication; while men who were hazardous drinkers reported less trust in their relationships compared to men who were abstainers (27). These associations are clearly complex and merit qualitative research to explore gender differences and the relevance of specific relationship dynamics.

According to dyadic interdependence theory, each partner is influenced by and affects the outcomes of his or her partner (28). Thus, the couple itself represents a critical level of analysis, particularly for HIV-related behaviors such as alcohol use and adherence to ART (29, 30). In SSA, health decisions and HIV-related health behaviors frequently happen at the couple or family level. Studies with HIV-positive couples in Malawi and South Africa have illustrated the influential role of primary partners in helping HIV-positive individuals maintain adequate adherence to ART (31, 32). With regard to alcohol use, a qualitative study in South Africa found that partner support for adherence depended on beliefs about the interaction of alcohol and ART. Some participants discouraged their HIV-positive partners from taking ART while drinking, while others encouraged their partners to take ART no matter what (9).

Alcohol use is often conceptualized as part of a syndemic, or a web of co-occurring and synergistic health and social challenges (33, 34). The SAVA syndemic—an entwinement of substance abuse, intimate partner violence (IPV), and AIDS—is a complex web of factors affecting health (33, 34) and has been applied to understand HIV risk in settings such as South Africa (35, 36). Other factors such as food insecurity, depression, and sexual compulsivity have been considered important syndemic factors (37, 38). In Uganda, food insecurity has been associated with women engaging in transactional sex (39), which is linked to HIV risk and poor ART adherence (40, 41). For individuals living with HIV, research finds that the more factors in the syndemic, the more profound the impact on adherence and viral load (42–44). However, less research has explored how syndemic factors, including alcohol use, play out in the context of couple relationships to affect ART adherence. Quantitative studies on syndemic factors and HIV risk from couples in the US highlight that a couples-focused approach is an important area of inquiry (45).

As part of a broader qualitative study on relationship dynamics and ART adherence in Malawian couples, we explored how alcohol consumption may impact couple relationships and ART adherence and conversely, how partners may impact each other’s alcohol consumption and ART adherence. In accordance with interdependence theory, we also explored whether one partner’s alcohol use influences the other partner’s ART adherence. Drawing on in-depth interviews with Malawian married couples who have mutually disclosed their HIV status and serve as each other’s designated treatment guardians, we examined the pathways linking alcohol use to ART adherence. We paid particular attention to how marriage and alcohol use intersect to shape ART adherence from both partners’ perspectives, and to the potential role of syndemic factors in these processes.

Methods

Study context

Approximately one-third of men in Malawi drink alcohol and 19% of men drink excessively (46). Alcohol consumption is significantly lower among women, with corresponding figures of 4% and 2% (46). In a sample of 211 married Malawian couples, in which this study was nested, 34% of men similarly reported currently drinking alcohol (unpublished data). Of these men, approximately half reported hazardous drinking based on the AUDIT-C scoring procedures (47). In southern Malawi, the site of this study, HIV prevalence is twice that of the northern and central regions, with 16% of women and 9% of men being HIV-infected (48). Nationally, two-thirds of HIV-positive Malawians are accessing ART (49). Individuals initiating ART select a treatment guardian (50), often the spouse, who is supposed to assist in a variety of ways from providing treatment reminders to providing food to take with ART. Most adult Malawians self-identify as married and marriage occurs early, with a median age of 19 for women and 23 for men in southern Malawi (48).

Study procedures

Between August and November 2016, we conducted in-depth interviews with 50 individuals in 25 couples. The sample size was determined at the start of the study based on our pilot research in South Africa with 24 couples (9, 31) and qualitative guidelines for reaching data saturation (51). Partners were interviewed separately. To be eligible, couples had to be at least 18 years old, in a non-polygamous union, have at least one HIV-positive partner (the “index patient”) who had disclosed their HIV status to the other partner, together for at least six months or since the start of ART, and report being more committed to each other than any other partner. We recruited fifteen couples who had an index patient in the process of initiating ART. These couples were known as Group 1 and were interviewed twice, once when starting ART and then three months later, to understand experiences over time. To include couples with a longer history of ART use, we recruited ten additional couples with an index patient who had been on ART for at least one year. These couples were known as Group 2 and were interviewed once. Our purpose was to include couples with a range of times on ART who may have varied perspectives, but not to contrast Groups 1 and 2. Thus, we conducted a total of 80 interviews. We recruited approximately equal numbers of index patients by gender, recruitment site, and HIV status of partner.

Recruitment took place at two HIV care clinics in Zomba district: Zomba District Hospital, a large public hospital, and Pirimiti, a private rural hospital. Research staff announced the study during health information sessions, and then interested index patients could approach the staff. Clinic staff also informed their patients of the study. Since most couples did not attend clinic appointments together unless initiating ART, index patients were given information sheets to give to partners who could then contact study staff if interested. Index patients were screened at the clinics, while partners were screened on the phone and then again at their first interview appointment. Both partners provided informed consent in private locations of the HIV clinics. Thus, to be enrolled in the study, both partners had to be interested in participating, meet eligibility criteria, and provide informed consent. At the end of the interview, each partner was given a small incentive for their time. Interviewers were trained in the identification of and proper response to issues of couple conflict/violence or coercion, and on how to facilitate referrals for domestic violence assistance. We compiled a list of community-based resources for couples, including services for domestic violence, which was systematically provided to every participant at the start of the study. This research received ethical approval from the National Health Science Research Committee in Malawi and the Committee on Human Research at the University of California San Francisco.

Prior to the start of data collection, the research assistants and research manager were trained by the study authors on the study procedures, interview guide, qualitative interviewing techniques such as probing, and translation/transcription, and ethical procedures. Research assistants were matched to participants by gender and conducted the interviews in Chichewa. Partners were interviewed separately, but simultaneously, in private areas of the HIV clinics. Interviews took place at the HIV clinics for convenience and safety of the interviewers and participants who lived across a large geographical area. The consent process emphasized that the interviewers were not healthcare providers or associated with clinics, and that responses would not be shared with healthcare providers or negatively impact their HIV care. Two interview guides were used. The index patient guide contained open-ended questions on relationship history (e.g., how the partners met, the marriage process), relationship dynamics (e.g., love, power, conflict), and experiences with HIV testing, care, and treatment (e.g., missed pills and appointments) and how the partner was involved. The partner guide contained similar topics, but questions focused on how the partner supported the index patient with HIV care and treatment.

Data analysis

The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and translated by research assistants fluent in both English and Chichewa. The quality of the transcripts was verified by the Malawian research manager. Both partners’ data were linked via a unique couple identifier included in the file names. Analysis activities started after receiving the full set of transcripts. To analyze the data at the couple-level, we developed a dyadic analysis approach based on framework analysis. Framework analysis uses data matrices to organize data into themes, allowing for comparative analysis across themes and cases, while maintaining the links to the raw quotes (52). This approach has been applied to analyze couple relationships in other studies on HIV in SSA (53, 54).

Our adapted approach consisted of the following steps. First, after reading each set of partners’ transcripts, the first author and a research assistant created 25 couple summary tables with a row for each topic in the interview guide (e.g., alcohol use, couple conflict, adherence, partner support) and two columns indicating what “she said” and “he said”. At the top of each summary table, we included a brief narrative highlighting each partner’s reports on the couple’s relationship, areas of consistency and discrepancy between partners, and major topics discussed. In comparatively analyzing couples’ accounts, we noted areas in which partners had incongruent accounts (e.g., regarding violence). In assessing these discrepancies, we examined the level of detail provided, other issues in the relationship that might provide clues, whether the information provided was consistent with other segments of the interview, and whether social desirability bias might influence the reporting on certain behaviors. Next, we created a data matrix with a row for each couple to summarize key factors affecting adherence (e.g., alcohol use, violence, food insecurity) with supporting quotes, and to identify patterns of factors across couples. Finally, the authors held weekly meetings to discuss similarities and differences between couples using the couple summaries, data matrices, and raw data, and to identify common themes affecting adherence. After identifying men’s alcohol use as a predominant theme, we re-examined and coded the raw data among the subset of alcohol-using couples to further understand the couple-level mechanisms linking alcohol use to ART adherence.

Findings

Sample characteristics

The mean age of the sample was 38 years old and the majority of couples (80%) had a primary school education or less. All couples were either married or cohabiting, with an average relationship duration of 12 years. Nearly two-thirds of couples were sero-discordant (64%) and in these couples, women and men were equally likely to be the HIV-positive partner. All spouses were each other’s designated treatment guardians.

Alcohol use patterns

In the present study, 10 of 25 couples reported that the husband currently or previously drank alcohol. The husband’s history of drinking was confirmed by both partners, although in a few couples, partners gave discrepant reports about whether the husband was still drinking. No couples reported that the female partner drank alcohol. Eight of the men were current drinkers at the time of interview. The remaining two men had quit drinking. Of the eight current drinkers, seven were HIV-positive and three had reduced or attempted to reduce their drinking because of their HIV diagnosis or due to problems in their marriage. The other five men gave no evidence that they had considered reducing drinking. Most men reported that they did not drink alcohol every day, although according to their own and their wives’ reports, they were heavy drinkers. Table 1 summarizes key characteristics of the 10 couples who reported prior or current alcohol use.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of couples (N=10) with a current or previous alcohol user

| ID | Group number | HIV and ART status | Alcohol use | Length of union | Relationship challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Group 1 | Wife HIV+, recently initiated ART Husband HIV- |

Husband current user | 5 years | Extramarital partners, couple conflict/IPV, instability, food insecurity |

| 2 | Group 1 | Wife HIV− Husband HIV+, recently initiated ART |

Husband current user | 12 years | Extramarital partners (past and possibly current), couple conflict/IPV, instability (separated), food insecurity |

| 4 | Group 1 | Wife HIV− Husband HIV+, recently initiated ART |

Husband quit but relapsed | 7 years | Extramarital partners in past |

| 5 | Group 1 | Wife HIV+, recently initiated ART Husband HIV+, on ART |

Husband reduced use | 13 years | Extramarital partners (husband) which stopped when he reduced drinking, food insecurity |

| 6 | Group 1 | Wife HIV+, on ART Husband HIV+, recently initiated ART |

Husband current user | 15 years | Extramarital partners, couple conflict/IPV, instability (separated), food insecurity |

| 8 | Group 1 | Wife HIV+, on ART Husband HIV+, recently initiated ART |

Husband current user | 2 years | Couple conflict/IPV, instability (considering separation/divorce), food insecurity |

| 16 | Group 2 | Wife HIV− Husband HIV+, on ART |

Husband reduced use | 14 years | Extramarital partners, IPV which stopped when he reduced drinking |

| 20 | Group 2 | Wife HIV+, on ART Husband HIV+, on ART |

Husband current user | 9 years | Extramarital partners, couple conflict/IPV, instability, food insecurity |

| 21 | Group 2 | Wife HIV+, on ART Husband HIV− |

Husband quit | 22 years | Food insecurity |

| 23 | Group 2 | Wife HIV+, on ART Husband HIV+, on ART |

Husband quit | 28 years | Food insecurity, couple conflict/IPV, extramarital partners in past, IPV (by husband) which stopped when he quit drinking |

Group 1 was interviewed twice. Group 2 was interviewed once.

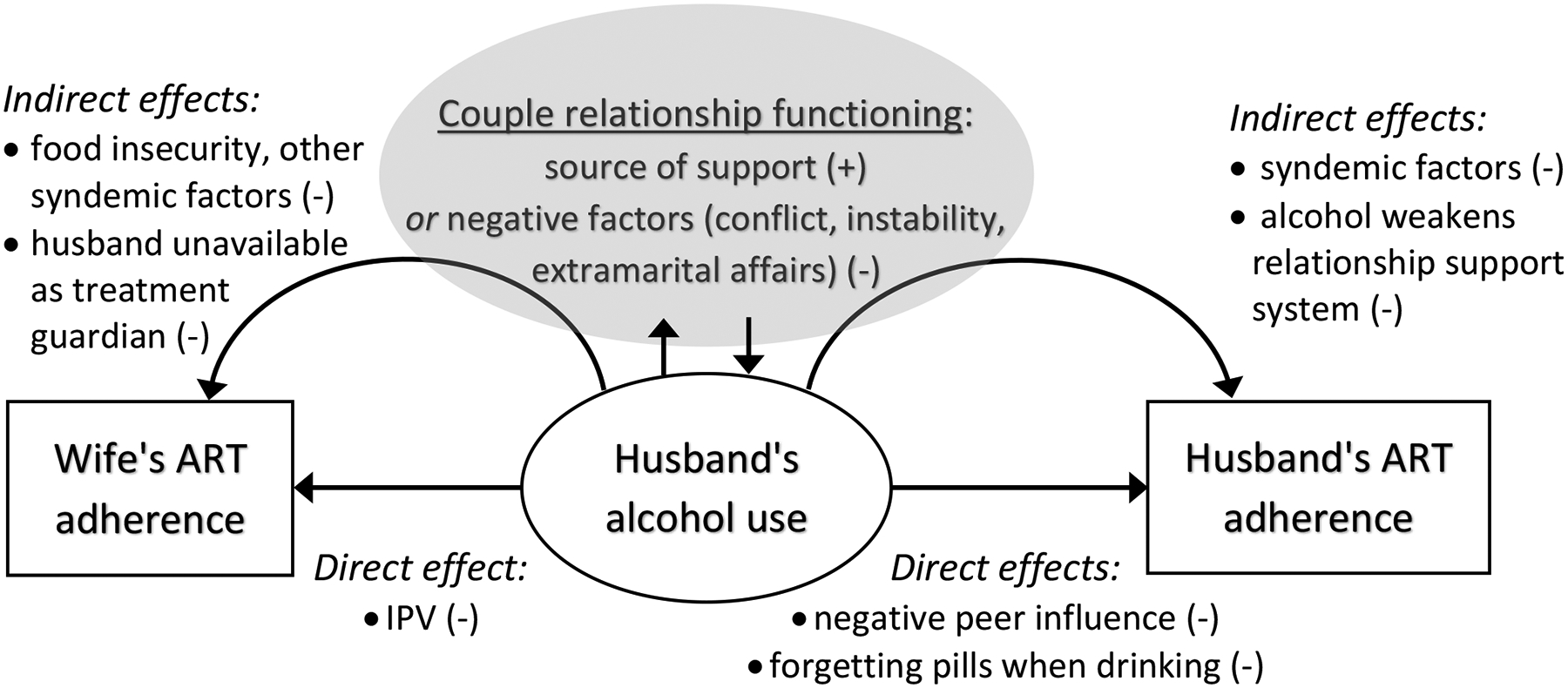

Conceptual model for couple interdependence around alcohol and ART use

By analyzing each couple as a unit, we identified how men’s alcohol use affects both their own ART adherence and their wives’ ART adherence. Wives described the ways in which they tried to reduce the negative impact of alcohol use on their husbands’ ART adherence. Couple relationship functioning appeared to play into these dynamics. While many women and men received support from their spouses for adherence, couples with poor relationship functioning such as conflict, IPV, and extramarital relationships, appeared to struggle with providing support, which may have exacerbated the negative impact of men’s alcohol use on adherence. Table 1 summarizes these challenges for each couple. As posited by syndemic theory, these overlapping challenges appear to operate synergistically to negatively impact ART adherence. Alcohol use and other syndemic factors (e.g., food insecurity) also affected adherence by damaging the support systems within relationships needed to maintain good adherence. In Figure 1, we present a conceptual model to summarize our findings and illustrate how couple interdependence impacts alcohol use and ART adherence in couples.

Figure 1:

Conceptual model to understand couple interdependence around alcohol use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART)

The buffering role of wives’ support on men’s drinking and ART adherence

Some wives urged their husbands to reduce their drinking or quit altogether, and/or supported their ART adherence out of concerns for their health. Recalling information learned from treatment counseling, participants consistently reported that healthcare workers discouraged alcohol use while on ART. Of the four men in this study who successfully reduced or quit drinking, all did so with considerable urging and support from their wives.

Lucy and Isaac (couple 23) had been together for over two decades, and both started ART in 2009 after learning they were HIV-positive. Lucy reported that Isaac had several sexual partners since testing HIV-positive, but he apologized and terminated these relationships (Isaac reports that he never had these relationships). Both partners reported severe and reciprocal IPV that revolved around allegations of his infidelity and occurred mostly when he was drinking. While Isaac continued to drink, Lucy kept advising him to quit drinking, stressing the importance of his health for the sake of the family. According to Lucy, Isaac’s drinking, as well as negative peer pressure from other drinkers, directly interfered with his medication adherence:

In 2012, he started missing medication. He restarted drinking beer… frequently. He even failed to take medications after arriving home from the beer drinking place, as people [there] were encouraging each other to stop the medication.

Isaac attempted to stop drinking multiple times but did not succeed until 2015 when he was diagnosed with tuberculosis and healthcare workers intervened on his alcohol use. When he stopped drinking, the couple stopped quarrelling over the money he was spending on alcohol instead of the household. Isaac says:

She told me that she did not want a man who drinks a lot, [thus] forgetting the poverty of his own house… Now I have left [stopped] all that I was doing [drinking]… She has made up her mind to stay with me forever, hence we are now one in everything.

Both partners reported that since then, they have lived together in peace and unity. Isaac stated, “The time I was drinking beer, she hated me. When I stopped taking beer she started loving me more.” He also attributes their unity and love to attending church services together and the encouragement received from church members on the importance of love.

Grace and Joseph (couple 16) were sero-discordant, with Joseph being HIV-positive. Joseph reported beating Grace in the past when he was drinking (although Grace reported he never beat her). By his account, his former drinking led to significant personal and relationship struggles, causing him to forget to take his medication.

Joseph: When I drank beer that day it was very difficult for me to remember to take my medication. My wife had to plead with me to be taking my medication but due to influence of beer I could not listen to her.

Interviewer: How frequently were you missing the time of taking your medication?

Joseph: In many cases each day I got drunk. I can say close to each day in a week, my wife had to shout at me for that behavior because she wanted me to get the treatment as told by the doctors.

Joseph stated that he had reduced his drinking to several times per year (which Grace confirmed) and stopped beating Grace. He explained that Grace played a role in this change by creatively preventing him from going to the drinking establishment.

Each day when I thought of going to the beer [place], she put those trousers I liked in water and put them on the drying line. Little by little I started to change, then I thought of quitting beer. I really stopped taking beer… [instead] I took my time chatting with my children and wife at home.

In some cases, women described how they focused on their partners’ ART adherence rather than the drinking. Some wives felt their partners’ drinking was manageable and not a problem. Wives of husbands who were HIV-infected and continued to drink often made a conscious decision to keep their husbands healthy to the best of their ability. This decision seemed connected to the need to maintain a functional household. Mary and James (couple 5), a sero-concordant couple, illustrate this. Although James had recently reduced his alcohol use, he continued to drink while taking ART. Mary seemed largely unbothered by his drinking as it did not cause significant problems for their family, but she continued to remind him to take his medication.

Mary: No, if there is a thing that I am proud of my husband for, it is that when he takes beer, he comes home.

Interviewer: Does it not make him to forget taking the pills?

Mary: No, he does not miss a day.

Interviewer: Why not?

Mary: I remind him… because if he is not taking the pills, he may fall sick and for him to be ill, it will make our household chores and tasks come to a stop.

Men’s alcohol use damages support systems needed for ART adherence

Men’s alcohol use could also negatively impact ART adherence by weakening supportive relationships, particularly those provided by their wives. All men on ART had designated their wives as treatment guardians and depended on their support for adherence. Therefore, if men’s drinking damaged the stability or unity of the relationship, their adherence could also be placed at risk. Conversely, as noted in the case of Lucy and Isaac (couple 23), some couples described a pattern in which relationship cohesion increased due to reduced alcohol use or other factors, and couples were more able to support each other with ART adherence.

Chisomo and Charles (couple 8) were both HIV-positive and had struggled with Charles’ alcohol use and numerous other challenges, including IPV and food insecurity, for the duration of their relationship. The wife, Chisomo, was first diagnosed with HIV and started on ART, which led to resentment and maltreatment from Charles. She explained that Charles damaged their relationship by beating her and spending money on beer instead of on food for the household, saying, “Since I got married, I have never experienced good times.” Both partners acknowledged that Chisomo worked hard to ensure that Charles took his pills and attended his clinic appointments. In the first interview, he said:

There would be no possibility that I would be missing my appointment days… I have my wife with me who is always close to me… She knows more about these things. She is the one who reminds me when I forget to take my medication.

However, Chisomo explained that when Charles was drinking, he resisted her advice related to having food and taking the mediation on time. Chisomo stated, “He said, ‘You don’t have the right to tell me what to do. I am the one who earns these things.’ Then I stopped advising him to avoid quarrels.” At the follow-up interview, the couple was considering divorce because of their persistent problems. Given that women are the primary caregivers in this setting and men benefit significantly from their wives’ health support, divorce could be detrimental to Charles’ ART adherence as well as overall health.

Ellen and Kondwani (couple 2) were sero-discordant, with Kondwani being the partner on ART. His continued alcohol use led to instability in the couple, which negatively affected his adherence. Although Ellen expressed pride in her husband’s ability to provide economically, she was unwilling to tolerate his drinking. In her first interview, she explained:

I told my current husband that I know what people experience in marriage. I was once married. If you plan to be drinking beer, I will not be happy with that behavior. I did not divorce my [former] husband because of beer drinking behavior, but if you will be drinking beer, you will not last long in marriage with me. He accepted… His salary is now used to buy household assets instead of spending the money on beer.

Upon follow-up, Ellen was less optimistic, reporting that Kondwani was still drinking beer and was now living away from home. She also alleged that he was still having other sexual partners. (Kondwani reported that he stopped having other partners since starting ART.) Ellen continued to support his ART adherence, calling to remind him to take pills and go to the hospital, but does not believe this is sustainable. She said, “I told [his parents] that I gave up on him because one day he told me that I should choose one thing between [letting him drink] beer and [losing the] marriage.”

Men’s alcohol use impacts wives’ ART adherence

One partner’s alcohol use impacts the couple unit and can hinder both partners’ ART adherence. Respondents described a variety of ways in which a husband’s drinking could negatively impact the wife’s adherence. For Chisomo and Charles (couple 8), both of whom were HIV-positive and on ART, Charles’ drinking greatly increased the likelihood that he would become violent. Chisomo explained how this abuse challenged her ART adherence.

When [my husband] has drunk beer, that is when it is my time to take my medication. He starts shouting and beating me, so I don’t have the chance to take my pills in such times… Sometimes when he is out drinking beer, I take my medication earlier at 6 p.m., before he arrives.

For Joyce and Mphatso (couple 6), both of whom were HIV-positive and on ART, Mphatso’s drinking interfered with his ability to be a responsible treatment guardian to Joyce. Mphatso would frequently return home from drinking after Joyce was supposed to take her pills and thus he was unable to remind her or confirm with her that she was taking her medication as prescribed. Joyce explained, “Most of the time he finds me already asleep and I have already taken my pills. I just remind myself that this is the time for me to take the pills.”

Jessie and Louis (couple 1), who were sero-discordant, experienced years of interpersonal conflict and IPV which impacted Jessie’s ART adherence. According to Jessie, Louis’ abuse was often a result of his drinking, and she was once beaten so severely that she miscarried (Louis did not disclose any abuse). Since Jessie started ART, Louis, who is HIV-negative, has been her treatment guardian. When asked who in the family is in charge of making decisions related to HIV care and treatment, she responded:

[My husband] is the one who checks everything. Is the patient taking medication? Is she taking medication at the right time? Is she eating food that will be helpful to her health? How is she feeling at night? Did she experience any problems? Let me ask her the problems that she is experiencing after starting medication… He has got a role to play.

Louis professed a commitment to these responsibilities, saying that he only drinks on occasion and that “nothing will disturb the medication of my wife.” However, Jessie interpreted the situation differently. Although she did not provide any examples of Louis failing to remind her to take pills, she explained that Louis’ drinking interfered with his ability to adequately support her emotionally or financially.

One day, he was drunk and other people had beaten him up and stolen his money. So when he got home, there was no food… I asked him why he went drinking and had his money stolen while leaving no food at home, considering that there is a little child. He said I should appreciate his love in the sense that he takes care of me regardless of the disease that I have.

Discussion

Although alcohol use is typically conceptualized in existing literature as an individual-level behavior, we find strong evidence that it is a family issue and affects both members of the couple. Notably, alcohol use was reported exclusively by men, which reflects population-level data from Malawi on alcohol use (46). While we argue for examining alcohol use as a couple-level concern, we acknowledge that in this study, the behavior and its impact were not reciprocal between partners. Rather, men’s drinking had a negative impact on both members of the couple, including on ART adherence, but also on couple conflict, IPV, food insecurity, and household poverty. Furthermore, men’s alcohol use could damage important support systems within the relationship. The negative impacts of alcohol on adherence and couple functioning may be buffered by wives’ efforts to reduce their husbands’ drinking or ameliorate the impact of drinking by supporting their husbands to take ART even when consuming alcohol.

Consistent with previous research (2, 8, 55), respondents described how alcohol use affects an individual’s ability to remember to take pills and to do it on time. However, the findings go beyond what has been previously presented in the literature to highlight the couple relationship as a focal point for analysis and the protective role of the couple relationship for alcohol-related adherence. As shown in our conceptual model in Figure 1, the findings also indicate the bi-directional nature of alcohol use and couple relationship functioning—which is consistent with other research from developed countries (14). Women described their attempts to positively influence their husbands’ alcohol use and ART adherence through a variety of tactics with the goal of keeping their husbands healthy. Conversely, alcohol use could damage their relationships and the support systems needed for ART adherence. Other research has found that negative relationship dynamics such as conflict or extramarital relationships can lead to alcohol use as a coping strategy (16). While our respondents did not report this phenomenon, this should be explored in future studies with couples in SSA.

This study also highlights the need for research and interventions to take into account the structural and social context in which these relationships are embedded. Although alcohol use and the demands of living with HIV were critical stressors for women and men in the study, these couples faced many other threats and challenges, including poverty and food insecurity. Building on the work of others on syndemic stress and HIV in couples (45), future studies could examine locally-meaningful syndemic factors to quantify how syndemic stress is manifested in couples, and impacts ART adherence and viral load. Further qualitative research is also needed to elucidate drinking patterns and drinking triggers among men in Malawi, including cultural norms surrounding alcohol use and how such norms may in turn be tied to poverty and structural factors. This additional information is key to understanding other potential barriers outside of the dyad that could limit the effectiveness of alcohol interventions for people living with HIV.

From a couple interdependence perspective, both the partner of the alcohol user and the relationship itself merit further investigation and should be considered in interventions to reduce alcohol use and promote ART adherence. This research also points to the importance of involving both members of a couple in efforts to promote ART adherence among alcohol-using couples, regardless of which partner is consuming alcohol. A man’s drinking can jeopardize his ART adherence even if his wife is a supportive treatment guardian. Likewise, his drinking should be addressed even when talking about her adherence. In the US, there is strong evidence that couple-based behavioral approaches to alcohol treatment are superior to individual-based approaches as they address relationship dynamics that often go ignored (56). Such interventions have also been shown to reduce IPV and improve relationship functioning (57), and may inform alcohol interventions for couples living with HIV in SSA.

Although few studies have addressed alcohol use in couples in SSA, a study from South Africa found that a couples-based approach involving both drinkers and their female partners was more effective at reducing men’s alcohol use than an individual-based alternative (58). There is tremendous untapped potential to adapt such interventions for alcohol-using couples to address HIV treatment behaviors and outcomes in SSA. As suggested by the participants, programs may also be needed to provide support to spouses of alcohol users for their own mental health and to cope with difficult circumstances. Support groups for family members of alcoholics that have arisen from the Alcoholics Anonymous movement (e.g., Al-Anon) may provide a useful starting point for conceptualizing such interventions (59).

Limitations

This study of alcohol use and ART adherence among couples emerged from a larger study, which aimed to more generally examine relationship functioning and ART adherence. Because the emergence of alcohol as a central theme in couples’ lives was unexpected, we did not recruit couples based on alcohol use, and therefore, the number of alcohol-using couples was relatively small. The fact that both partners were interviewed, in most cases twice, is a strength of this study. Yet we also acknowledge that couples may have presented themselves in socially desirable ways and under-estimated or omitted behaviors such as women’s alcohol use, IPV, and lapses in ART adherence. Nonetheless, we believe that interviewing both members of the couple increased the rigor of the data, and we note that participants were open in discussing a number of sensitive behaviors. We believe that the portrait of couple relationship functioning, ART adherence, and alcohol use which emerged is accurate, although it may not be transferable to other populations of HIV-affected couples.

Conclusion

Although alcohol use has long been recognized as being detrimental to the health of people living with HIV, our findings demonstrate that an individual’s alcohol use can negatively impact not only his or her own ART adherence but also that of a partner. This impact may be buffered by the quality of a couple’s relationship and, as demonstrated by the couples in this study, by wives’ attempts to positively influence men’s alcohol usage and ART adherence. On the other hand, couple interdependence could have negative consequences for couple relationship functioning, food insecurity, and ART adherence for both partners. Further research is needed to untangle these complex webs of risk factors to inform interventions for alcohol reduction, ART adherence, and healthy relationship functioning among HIV-affected couples.

References

- 1.Galvan FH, Bing EG, Fleishman JA, et al. The prevalence of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking among people with HIV in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(2):179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, et al. Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(2):180–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giordano TP, Hartman C, Gifford AL, et al. Predictors of retention in HIV care among a national cohort of US veterans. HIV Clin Trials. 2009;10(5):299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chander G, Lau B, Moore RD. Hazardous alcohol use: a risk factor for non-adherence and lack of suppression in HIV infection. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2006;43(4):411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baum MK, Rafie C, Lai S, et al. Alcohol use accelerates HIV disease progression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010;26(5):511–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hahn JA, Samet JH. Alcohol and HIV disease progression: weighing the evidence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(4):226–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braithwaite RS, Bryant KJ. Influence of alcohol consumption on adherence to and toxicity of antiretroviral therapy and survival. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33(3):280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kekwaletswe CT, Morojele NK. Alcohol use, antiretroviral therapy adherence, and preferences regarding an alcohol-focused adherence intervention in patients with human immunodeficiency virus. Patient Preference & Adherence. 2014;8:401–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conroy AA, McKenna SA, Leddy A, et al. “If She is Drunk, I Don’t Want Her to Take it”: Partner Beliefs and Influence on Use of Alcohol and Antiretroviral Therapy in South African Couples. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(7):1885–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fatch R, Emenyonu NI, Muyindike W, et al. Alcohol Interactive Toxicity Beliefs and ART Non-adherence Among HIV-Infected Current Drinkers in Mbarara, Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2016:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, White D, et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of interactive toxicity beliefs regarding mixing alcohol and antiretroviral therapies among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(6):449–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, White D, et al. Alcohol and adherence to antiretroviral medications: interactive toxicity beliefs among people living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012;23(6):511–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levitt A, Derrick JL, Testa M. Relationship-specific alcohol expectancies and gender moderate the effects of relationship drinking contexts on daily relationship functioning. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2014;75(2):269–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levitt A, Cooper ML. Daily alcohol use and romantic relationship functioning: Evidence of bidirectional, gender-, and context-specific effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36(12):1706–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Homish GG, Leonard KE. Marital quality and congruent drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(4):488–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez LM, Neighbors C, Knee CR. Problematic alcohol use and marital distress: An interdependence theory perspective. Addiction Research & Theory. 2014;22(4):294–312. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leonard KE, Rothbard JC. Alcohol and the marriage effect. Journal of studies on Alcohol, supplement. 1999(13):139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gotlib IH, McCabe SB. Marriage and psychopathology. 1990.

- 19.Halford WK, Bouma R, Kelly A, et al. Individual psychopathology and marital distress: Analyzing the association and implications for therapy. Behav Modif. 1999;23(2):179–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Farrell T, Rotunda R. Couples interventions and alcohol abuse. Clinical handbook of marriage and couples interventions. 1997:555–88. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Homish GG, Leonard KE. The drinking partnership and marital satisfaction: The longitudinal influence of discrepant drinking. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morojele NK, Kekwaletswe CT, Nkosi S. Associations between alcohol use, other psychosocial factors, structural factors and antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence among South African ART recipients. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(3):519–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sileo KM, Simbayi LC, Abrams A, et al. The role of alcohol use in antiretroviral adherence among individuals living with HIV in South Africa: Event-level findings from a daily diary study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;167:103–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denison JA, Koole O, Tsui S, et al. Incomplete adherence among treatment-experienced adults on antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. AIDS (London, England). 2015;29(3):361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruark A, Kajubi P, Ruteikara S, et al. Couple Relationship Functioning as a Source or Mitigator of HIV Risk: Associations Between Relationship Quality and Sexual Risk Behavior in Peri-urban Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2017:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woolf-King S, Conroy A, Fritz K, et al. Alcohol use and relationship quality among South African couples: Implications for couples-based HIV interventions International AIDS Conference; July 18–22, 2016; Durban, South Africa [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelley HH, Thibalt JW. Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. New York: Wiley; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karney BR, Hops H, Redding CA, et al. A Framework for Incorporating Dyads in Models of HIV-Prevention. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(2):189–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rusbult C, Arriaga X. Interdependence theory In: Duck S, editor. Handbook of personal relationships. 2nd ed London, UK: Wiley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conroy A, Leddy A, Johnson M, et al. ‘I told her this is your life’: relationship dynamics, partner support and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among South African couples. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2017;19(11):1239–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conroy AA, McKenna SA, Comfort ML, et al. Marital infidelity, food insecurity, and couple instability: A web of challenges for dyadic coordination around antiretroviral therapy. Soc Sci Med. 2018;In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singer M. A dose of drugs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS, part 2: further conceptualizing the SAVA syndemic. Free Inq Creat Sociol. 2006;34(1):39–53. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singer M. A dose of durgs, a touch of violence, a case of AIDS: conceptualizing the SAVA epidemic. Free Inq Creat Sociol. 1996;24(2):99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russell BS, Eaton LA, Petersen-Williams P. Intersecting epidemics among pregnant women: alcohol use, interpersonal violence, and HIV infection in South Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10(1):103–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hatcher AM, Colvin CJ, Ndlovud N, et al. Intimate partner violence among rural South African men: alcohol use, sexual decision-making, and partner communication. Culture Health & Sexuality. 2014;16(9):1023–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai A, Burns B. Syndemics of psychosocial problems and HIV risk: A systematic review of empirical tests of the disease interaction concept. Soc Sci Med. 2015;139:26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parsons JT, Grov C, Golub SA. Sexual compulsivity, co-occurring psychosocial health problems, and HIV risk among gay and bisexual men: further evidence of a syndemic. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):156–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller CL, Bangsberg DR, Tuller DM, et al. Food Insecurity and Sexual Risk in an HIV Endemic Community in Uganda. AIDS Behavior. 2011;15:1512–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiser SD, Palar K, Frongillo EA, et al. Longitudinal assessment of associations between food insecurity, antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2014;28:115–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiser SD, Tuller DM, Frongillo EA, et al. Food insecurity as a barrier to sustained antiretroviral therapy adherence in Uganda. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friedman MR, Stall R, Plankey M, et al. Effects of syndemics on HIV viral load and medication adherence in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. AIDS (London, England). 2015;29(9):1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blashill AJ, Bedoya CA, Mayer KH, et al. Psychosocial syndemics are additively associated with worse ART adherence in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(6):981–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Garofalo R, et al. An index of multiple psychosocial, syndemic conditions is associated with antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(4):185–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Starks TJ, Tuck AN, Millar BM, et al. Linking syndemic stress and behavioral indicators of main partner HIV transmission risk in gay male couples. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(2):439–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Msyamboza KP, Ngwira B, Dzowela T, et al. The burden of selected chronic non-communicable diseases and their risk factors in Malawi: nationwide STEPS survey. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bush K, Kivlahan D, McDonell M, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Statistical Office (NSO) [Malawi] and ICF. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2015–16. Zomba, Malawi, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NSO and ICF, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 49.UNAIDS. UNAIDS country report on Malawi. http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/malawi. 2018.

- 50.Ministry of Health Malawi. 3rd Edition of the Malawi Guidelines for Clinical Management of HIV in Children and Adults. Lilongwe, Malawi: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–62. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nicholls CM, et al. Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Starmann E, Collumbien M, Kyegombe N, et al. Exploring couples’ processes of change in the context of SASA!, a violence against women and hiv prevention intervention in Uganda. Prevention science. 2017;18(2):233–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mugweni E, Pearson S, Omar M. concurrent sexual partnerships among married Zimbabweans–implications for HIV prevention. International journal of women’s health. 2015;7:819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lyimo RA, de Bruin M, van den Boogaard J, et al. Determinants of antiretroviral therapy adherence in northern Tanzania: a comprehensive picture from the patient perspective. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Powers MB, Vedel E, Emmelkamp PM. Behavioral couples therapy (BCT) for alcohol and drug use disorders: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(6):952–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fals-Stewart W, Clinton-Sherrod M. Treating intimate partner violence among substance-abusing dyads: The effect of couples therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40(3):257. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wechsberg WM, Zule WA, El-Bassel N, et al. The male factor: Outcomes from a cluster randomized field experiment with a couples-based HIV prevention intervention in a South African township. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:307–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Timko C, Young LB, Moos RH. Al-Anon family groups: Origins, conceptual basis, outcomes, and research opportunities. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery. 2012;7(2–4):279–96. [Google Scholar]