Abstract

With the launch of new Government of India's initiative Ayushman bharat that envisages conversion of all subcenters into health and wellness centers, the role of nursing professionals in primary health care will be undergoing paradigm shift. Nurses are approximately two-third of the population of health workforce in India. Nurses’ scope of work has widened with additional roles and responsibilities due to shift in the pattern of burden of diseases. The emergence of zoonotic infectious diseases has further enlarged their responsibilities. The main areas, which need attention, are development of nursing workforce, selection and recruitment, placement as per specialization, and preservice and in-service training related to zoonotic surveillance. This article attempts to discuss the role of nurses under emerging zoonotic disease infections.

Keywords: Burden of diseases, nursing cadre, primary health care, zoonotic diseases

INTRODUCTION

Nursing cadre is the backbone of health system. Nurses’ role is very critical in delivering health services and increasing the equity of health-care provision. They are the agents of change within the health system and play a key role in addressing various social determinants of health. The role of nurses in primary health care encompasses autonomous and collaborative care of individuals of all ages, families, groups, and communities, sick or well in community settings. It includes the promotion of health; the prevention of illness; and the care of ill, disabled, and dying people.[1] India is undergoing a major epidemiological transition. Over the last 26 years, the country's disease patterns have shifted. Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and injuries are increasingly contributing to the overall disease burden. NCD-related burden of diseases in 2016 increased from 37.9% to 61.8%, and burden due to injuries changed from 8.5% to 10.7%. The life expectancy at birth improved in India from 59.7 years in 1990 to 70.3 years in 2016 for females and from 58.3 years to 66.9 years for males.[2] Mortality due to communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases (CMNNDs) has declined substantially. There has been a notable progress in the prevention, control, and even eradication of infectious diseases, all leading to a change in the role of nurses in primary health care from CMNNDs to NCDs and injuries. Along with that, they have the crucial role in the recently announced health and wellness centers (H and WCs) and National Health Protection Scheme which will cover more than half a billion population in India. However, in developing countries like India, there has been an emergence of new and reemergence of earlier seen infectious diseases in a more virulent form after a period of decline or disappearance. The role of nurses has consequently further expanded to keep the public informed about these infectious diseases and risks involved while at the same time working toward the prevention of the spread of the disease.

CURRENT SCENARIO

In India, different leadership positions are designated separately for community (public health nurse) and clinical nurses at the primary health-care level. Auxiliary nurse Midwife (ANM) is the first-level community nurse, and lady health visitor (LHV) is the supervisor of the ANMs. ANMs have a crucial role in health-care delivery, as they are responsible for the implementation of health programs and extending the outreach clinical services at the community level. They coordinate with community-level health volunteers called accredited social health activist (ASHAs) who are about a million in numbers and the volunteers of woman and child health called Anganwadi workers (AWWs), for smooth delivery of health-care services. Both ASHA and AWWs look after about 1000 population each. The clinical nurses are categorized into registered nurses (RNs) and registered midwives (RMs). According to the National Health Profile 2018, there are 1,980,539 RNs and RMs and 841,279 ANMs and 56,367 LHVs serving in India as of 2016.[3] As of March 31, 2018, the country had a shortfall of 10,907 of ANMs, 10,557 LHVs, 16,981 male supervisors, 3673 medical officers, and 8262 nurses at primary health care (PHC) and community health centers (CHC) level.[4] Even out of the sanctioned posts, a significant percentage of posts were vacant at the primary level. For instance, 12.9% ANM, 41.2% health worker (males), 28.6% LHV, 50.7% health assistants (male), and 14.3% nursing staff positions at PHCs and CHCs are vacant. India is far away from its aim of two nurses and one ANM per doctor to be achieved by the year 2025.[5]

ROLE IN HEALTH AND WELLNESS CENTERS

Subcenters are the peripheral contact of the community with the health system. Currently, they do not provide services for NCDs, injuries, old-age problems, mental health, etc., In order to improve the health-seeking behavior at community, the National Health Policy 2017 had envisioned converting the existing subcenters into H and WCs which aim at providing comprehensive primary health-care delivery.[6] This is based on the observation that optimum utilization of subcenters in meeting out their key objective is hindered due to factors such as poor infrastructure, weak monitoring and supportive supervision, lack of workforce, and geographical barriers.[7] The role of ANMs will expand to include providing promote and preventive health care, first aid, and basic primary health care and ensure referral to higher levels of care, as appropriate.

ROLE IN ZOONOSIS SURVEILLANCE, PREVENTION, AND CONTROL

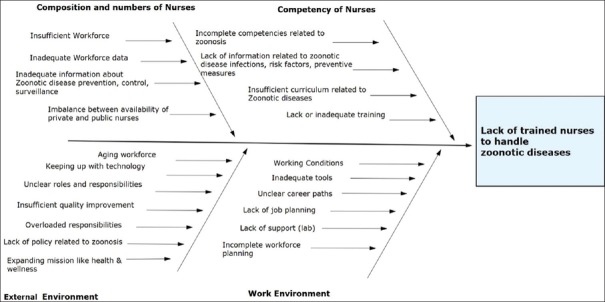

An estimated 75% of emerging infectious disease are zoonotic, primarily of viral origin.[8] There are more than 800 zoonotic pathogens known to affect human beings, nearly 20 to 30 from cats and dogs.[9] Recently emerged zoonotic diseases include Ebola, Avian Influenza, severe acute respiratory syndrome, and bovine spongiform encephalopathy.[8,10,11] People who are unvaccinated, very young or elderly, immunosuppressed, or pregnant, or who have injuries are more susceptible to infections. The prevention and control of zoonotic diseases necessitates having effective methods for stopping or reducing agent transmission, early case detection, high-quality laboratory facilities, educating the population about the infections, and a robust surveillance for measuring progress and providing information that can be used to make changes as required.[12] Health-care providers, physicians, clinics, and hospitals generally base the information on zoonotic infections on notifiable reports. For effective surveillance records of patients, hospital, laboratory, and death records also need to be included. In addition, a dedicated epidemiological investigation to measure the morbidity and mortality impacts of specific zoonotic diseases at community levels, together with their seasonality and geographical location, and other risk factors, needs to be carried out. These activities require collaboration between veterinarians, health-care providers, nurses, policymakers, and the environmentalists in a joint surveillance approach called as “One Health” as it has a greater impact on animal and human health.[11] The number of veterinary hospitals in India is 11,367 as of March 2015, and their availability and access in rural areas is poor.[13] The number of registered veterinarians is 63,000, which is not adequate as per the requirement.[14] This adds extra responsibility on public health nurses as they are closely linked with human health. Several factors related to availability, infectious disease knowledge, external environment, and work environment influence the effective participation of the public health workforce (nurses) in zoonosis surveillance, prevention, and control [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Factors affecting the public health nurse workforce related to zoonosis

These factors can be addressed through effective leadership and communication, capacity building, changing the nursing curriculum to include zoonotic disease surveillance, data-driven activities, policy changes, and adopting the One Health approach to ensure multi-stakeholder collaboration.

CONCLUSION

Due to the changing pattern of demography and epidemiology of disease conditions and an augmentation of nursing cadre role at primary health-care institutions, it is essential to enhance the capacity of nursing staff at community level related to zoonotic diseases. Their curriculum and job description need to be revised to address zoonotic disease prevention and control in India. ANMs move around in community and frequently come across animals and people in close contact with animals. They need to be provided training regarding the risk factors associated with zoonotic infections (pet and wild animals) and its prevention so that they can monitor and identify such cases in their community. Most of the ANMs join and retire as ANMs after 30–35 years of service in health care. The LHV and supervisor positions to which they can be promoted, remain vacant which further demotivates them. Nurses in India prefer working in the public sector because it pays better than the private sector.[15,16] More than half of the nurses in India are employed by central and state governments, and opportunities for public sector employment have increased since the launch of the National Rural Health Mission in 2005.[17,18,19] They also need management and basic leadership training to effectively manage their work and improve health outcomes. There needs to be a system where public health nurses work together with veterinarians and animal health workforce so that there is exchange of information between them.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nursing Definitions. [Last assessed on 2018 Oct 11]. Available from: https://wwwicnch/nursing-policy/nursing-definitions .

- 2.Indian Council of Medical Research, Public Health Foundation of India, and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. India: Health of the Nation's States – The India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative. New Delhi, India: Indian Council of Medical Research, Public Health Foundation of India, and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Health Profile (NHP) of India-2018, Central Bureau of Health Intelligence, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. [Last assessed on 2018 Oct 12]. Available from: http://www.cbhidghs.nic.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=2&sublinkid=88&lid=1138 .

- 4.Rural Health Statistics, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 5.High Level Expert Group Report on Universal Health Coverage in India. Planning Commission of India. 2011. Nov, [Last assessed on 2019 Oct 17]. Available from: http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/rep_uhc0812.pdf .

- 6.National Health Policy-2017. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. [Last assessed on 2018 Oct 12]. Available from: https://mohfwgovin/documents/policy .

- 7.Kumar S, Rinu PK. Leadership skills for nurses. JOJ Nurs Health Care. 2018;8:555747. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor LH, Latham SM, Woolhouse ME. Risk factors for human disease emergence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:983–9. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams CJ, Scheftel JM, Elchos BL, Hopkins SG, Levine JF. Compendium of veterinary standard precautions for zoonotic disease prevention in veterinary personnel: National association of state public health veterinarians: Veterinary infection control committee 2015. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2015;247:1252–77. doi: 10.2460/javma.247.11.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451:990–3. doi: 10.1038/nature06536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heymann DL, Dar OA. Prevention is better than cure for emerging infectious diseases. BMJ. 2014;348:g1499. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belay ED, Kile JC, Hall AJ, Barton-Behravesh C, Parsons MB, Salyer S, et al. Zoonotic Disease Programs for Enhancing Global Health Security. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2017:23. doi: 10.3201/eid2313.170544. doi:103201/eid2313170544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. [Last assessed on 2019 Oct 03]. Available from: https://community.data.gov.in/veterinaryhospitalspolyclinics-in-various-states-and uts-as-on-31-03-2015/

- 14.Express Special: 30 crore cattle and rising, but where are the country’s vets? Indian Express. 2019. [Last accessed on 2019 Oct 17]. Available from: https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/30-crore-cattle-and-rising-but-where-are-thecountrys- vets/

- 15.Biju BL. Angels are turning read: Nurses’ strikes in Kerala. Econ Polit Wkly. 2013;48:52. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nair S. Nurses’ strikes in Delhi: A status question. Econ Polit Wkly. 2010;45:14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nair KS. Human resources for health in India: An overview. [Last assessed on 2018 Oct 12];Int J Health Sci Res. 2015 5:465. Available from http://wwwijhsrorg/IJHSR_ Vol 5_Issue 5_May2015/64pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynolds J, Wisaijohn T, Pudpong N, Watthayu N, Dalliston A, Suphanchaimat R, et al. Aliterature review: The role of the private sector in the production of nurses in India, Kenya, South Africa and Thailand. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:14. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao KD, Bhatnagar A, Berman P. India Health Beat. New Delhi: Public Health Found India and World Bank; 2009. India’s health workforce: Size, composition, and distribution; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]