Abstract

Human settlement of Madagascar traces back to the beginning of the first millennium with the arrival of Austronesians from Southeast Asia, followed by migrations from Africa and the Middle East. Remains of these different cultural, genetic, and linguistic legacies are still present in Madagascar and other islands of the Indian Ocean. The close relationship between human migration and the introduction and spread of infectious diseases, a well-documented phenomenon, is particularly evident for the causative agent of leprosy, Mycobacterium leprae. In this study, we used whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and molecular dating to characterize the genetic background and retrace the origin of the M. leprae strains circulating in Madagascar (n = 30) and the Comoros (n = 3), two islands where leprosy is still considered a public health problem and monitored as part of a drug resistance surveillance program. Most M. leprae strains (97%) from Madagascar and Comoros belonged to a new genotype as part of branch 1, closely related to single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) type 1D, named 1D-Malagasy. Other strains belonged to the genotype 1A (3%). We sequenced 39 strains from nine other countries, which, together with previously published genomes, amounted to 242 genomes that were used for molecular dating. Specific SNP markers for the new 1D-Malagasy genotype were used to screen samples from 11 countries and revealed this genotype to be restricted to Madagascar, with the sole exception being a strain from Malawi. The overall analysis thus ruled out a possible introduction of leprosy by the Austronesian settlers and suggests a later origin from East Africa, the Middle East, or South Asia.

Keywords: leprosy, Mycobacterium leprae, Madagascar, Comoros, genomics, phylogeography

Introduction

Leprosy was declared to be eliminated by the government of Madagascar in 2010, but the disease remains a public health problem, with more than 1,000 new cases reported annually since 2007 (Raharolahy et al., 2016; Suttels and Lenaerts, 2016; WHO, 2019). This is certainly an underestimate. Social exclusion and stigmatization are still common in Madagascar (Raharolahy et al., 2016), where approximately 25% of the new cases manifest with grade 2 disabilities, indicating late diagnosis (Raharolahy et al., 2016; Suttels and Lenaerts, 2016). Despite an efficient leprosy control program, the Comoros are still considered a highly endemic area, with a constant average of 400 new cases documented annually for an average population of 400,000 inhabitants since 2008 and 275 new cases in 2018 (Ortuno-Gutierrez et al., 2019; WHO, 2019). However, the relapse rate is low and only 1.8% of new cases present with grade 2 disability (Hasker et al., 2017; Ortuno-Gutierrez et al., 2019). In the last report of the drug resistance surveillance network, resistance to rifampicin (rpoB), dapsone (folP1), and quinolones (gyrA) was observed only in three primary cases between 2009 and 2015 in Madagascar (Raharolahy et al., 2016; Cambau et al., 2018). No information is currently available for the Comoros.

Leprosy is mainly caused by the non-cultivable pathogen Mycobacterium leprae and, to a lesser extent, Mycobacterium lepromatosis (Han et al., 2008). The M. leprae genotyping system is characterized by four single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) types (1–4) and 16 SNP subtypes (A–P) divided into eight branches (Monot et al., 2009; Schuenemann et al., 2018). In Madagascar and the Comoros, little is known about the genetic background of circulating M. leprae strains. Two epidemiological studies reported the presence of the genotype 1D in Madagascar, but only seven isolates were studied so far (Monot et al., 2009; Reibel et al., 2015). No information is available about the strains currently circulating in the Comoros. Although our inability to cultivate the pathogen in vitro has hampered research, recently developed methods allow the sequencing of leprosy bacilli DNA directly from human samples (Schuenemann et al., 2013; Avanzi et al., 2016; Benjak et al., 2018).

Despite Madagascar’s proximity to mainland Africa, the genetic, cultural, and archeological evidence indicate that the Malagasy and the Comorans, the inhabitants of Madagascar and the Comoros, respectively, are of mixed African, Indonesian, and Middle Eastern ancestry (Dewar and Wright, 1993; Burney et al., 2004; Ratsimbaharison and Ellis, 2010; Pierron et al., 2014, 2017). As with several other infectious diseases (Insitute of Medicine, 2010), leprosy also exemplifies the correlation between the dissemination of pathogens and human migrations (Monot et al., 2009). However, establishing the origin of M. leprae in an admixed population such as the Malagasy requires comprehensive molecular characterization of the pathogen.

In this investigation, we aimed to characterize the genetic background and predict the origin of the M. leprae strains circulating in Madagascar and the Comoros using whole-genome sequencing (WGS).

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out under the ethical consent of the WHO Global Leprosy Programme surveillance network. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients and Clinical Samples From Madagascar and the Comoros

A total of 60 skin biopsies from 51 suspected leprosy cases from Madagascar (n = 48) and the Comoros (n = 3), collected between 2013 and April 2017, were obtained from the Leprosy National Reference Laboratory [Centre d’Infectiologie Charles Mérieux (CICM), Antananarivo, Madagascar] and the Centre National de Référence des Mycobactéries et de la Résistance des Mycobactéries aux Antituberculeux (CNR MyRMA, Paris, France) for WGS characterization (Supplementary Table S1). Additionally, a total of 40 samples were collected after May 2017 at the Centre d’Infectiologie Charles Merieux from 40 suspected or diagnosed leprosy cases for molecular drug-susceptibility testing and genotyping (Supplementary Table S1).

Samples were collected at health facilities by medical staff (Supplementary Table S1). Three DNA extracts (B204, B171, and B191; Supplementary Table S1) from a previous investigation at the Institut Pasteur were also included (Monot et al., 2005).

Additional Samples for Genotyping Screening

DNA samples were obtained from ongoing or previous studies (Monot et al., 2005; Tió-Coma et al., 2019, 2020) from countries where the M. leprae genotype 1D was previously reported—Nepal (n = 25), Venezuela (n = 15), Bangladesh (n = 11), Brazil (n = 5), Chad (n = 4), Antilles (n = 3), India (n = 1), and Congo (n = 1)—for genotyping by PCR and WGS (Supplementary Tables S2, S3). Additional samples from two Austronesian countries, Philippines (n = 18), and Indonesia (n = 5), were also included.

DNA Extractions

The choice of the DNA extraction method for the samples from Madagascar and Comoros was influenced by initial results obtained by Ziehl–Neelsen (ZN) staining and standard PCR previously performed on site (Supplementary Table S1). DNA extraction for initial screening at reference laboratories (CICM and CNR-MyRMA) was carried using the freeze–boiling method as previously described (Woods and Cole, 1989). Around 50–100 mg of all previously characterized PCR- or ZN-positive skin biopsies were re-extracted using the host depletion (HD) method (Avanzi et al., 2016; Benjak et al., 2018). PCR- and ZN-negative biopsies and samples from the second screening step were extracted using the quicker total DNA extraction method (Avanzi et al., 2016; Girma et al., 2018; Supplementary Table S1). For samples collected outside Madagascar and the Comoros, the DNA extraction methods used are described in Supplementary Table S2.

PCR Amplification of Specific Loci, Molecular Drug Resistance Screening, and Genotyping by PCR Sequencing

Detection of M. leprae was performed for the first and second screening (Supplementary Table S1) on all samples, as recommended (WHO SEARO/Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2017), using the M. leprae-specific repetitive element (RLEP) primers (Table 1). M. lepromatosis-specific PCR (primers LPM244) was performed on all samples that were negative for M. leprae (Table 1). To identify genotype-specific SNPs, primers were designed using the Primer3 web tool1 and are described in Table 1. For each sample, 5 μl of the starting materials, negative control (water) or positive control (M. leprae DNA strain Thai-53, NR19352) was used in 50 μl reactions using the Accustart PCR Mastermix (Quantabio, Beverly, MA, United States), and quality was assessed as previously described (Avanzi et al., 2016). Amplification started with a 3 min initial denaturation step at 94°C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s denaturation at 94°C, 30 s annealing at 58°C (all PCR primers in Table 1), and extension at 72°C for 30 s; final extension was then at 72°C for 5 min. Amplicon sequencing was done by Genewiz (United Kingdom) or Microsynth (Switzerland).

TABLE 1.

List of primers used in this study.

| Primer name | Target | Purpose | Amplicon size (bp) | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | Nucleic acid modification between strains | References |

| RLEP-F | RLEP | Detection of M. leprae by | 450 | TGAGGCTTCGTGTGCTTTGC | – | Singh et al., 2015 |

| RLEP-R | RLEP | PCR | ATCTGCGCTAGA AGGTTGCC | – | ||

| RLEPq-F | RLEP | Detection of M. leprae by | 70 | GCAGTATCGTGTTAGTGAA | – | Truman et al., 2008 |

| RLEPq-R | RLEP | quantitative PCR | CGCTAGAAGGTTGCCGTATG | – | ||

| RLEPq-P | RLEP | FAM-TCGATGATCCGGCCGTCGGCG QSY | – | |||

| LPM244-F | hemN | Detection of | 244 | GTTCCTCCACCGACAAACAC | – | Singh et al., 2015 |

| LPM244-R | M. lepromatosis | TTCGTGAGGTACCGGTGAAA | – | |||

| rpoB-For | rpoB | Amplification of the drug | 255 | CTGATCAATATCCGTCCGGT | – | WHO SEARO/Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2017 |

| rpoB-Rev | resistance-determining region of rpoB | CGACAATGAACCGATCAGAC | – | |||

| folP1-For | folP1 | Amplification of the drug | 254 | CTTGATCCTGACGATGCTGT | – | |

| folp1-Rev | resistance-determining region of folP1 | CCACCAGACACATCGTTGAC | – | |||

| gyrA-For | gyrA | Amplification of the drug | 225 | ATGGTCTCAAACCGGTACATC | – | |

| gyrA-Rev | resistance-determining region of gyrA | TACCCGGCGAACCGAAATTG | – | |||

| SNP-2921694-F | ml2446 | Specific to 1D-Malagasy | 169 | TGTATGAACGCTGGGCAGTA | A1015G | This study |

| SNP-2921694-R | genotype | TCAACCGGGTCACCATAGAT | ||||

| SNP-3016895-F | ml2535 | Specific to 1D genotype | 199 | GAGCCACTATTTCCCGACAA | C3541A | This study |

| SNP-3016895-R | outside Madagascar | CGTCGTCGATGAGCAAGTAA |

qPCR of RLEP, an M. leprae-Specific Region, Prior to WGS

All DNA samples extracted at EPFL were subjected to quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis to detect M. leprae prior to WGS. The repetitive element RLEP was quantified using TaqMan® PCR amplification as described previously, with minor modifications (Truman et al., 2008). A total of 3 μl of each purified DNA sample, or the positive control (DNA from Thai-53, NR-19352) or the negative control (water), was added to a total PCR reaction volume of 20 μl containing 10 μl of TaqPath ProAmp master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States), 900 nM of each forward (RLEPq-F) and reverse (RLEPq-R) primer, and 250 nM of the hydrolysis probe (RLEPq-P) (Table 1). The reaction mixtures were prepared in triplicate and amplification started with an initial denaturation step of 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min 60°C, using the QuantStudio 3 real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States). Data analysis was performed with the Thermo Fisher Connect Cloud2, and the mean cycle threshold (Ct) was calculated for each sample. qPCR values were also used to evaluate the relative amount of M. leprae DNA in each sample and provide a GO/NO GO answer prior to WGS.

Library Preparation and Comparative Genomic Analysis

Up to 1 μg of DNA in 50 μl was fragmented to 300–400 bp by Adaptive Focused Acoustics on a Covaris S2 instrument (Covaris) using the manufacturer’s protocol. After a 1.8 × ratio cleanup using KAPA Pure beads (Roche, Switzerland), DNA library preparation was performed using the KAPA HyperPrep kit (Roche, Switzerland) and the KAPA dual indexes, as described elsewhere (Benjak et al., 2018). After the final amplification step, libraries were quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS or BR Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States) and the fragment size assessed on a Fragment Analyzer (Advanced Analytical Technologies, Inc., Ankeny, IA, United States). Finally, libraries were multiplexed and sequenced using single-end reads on Illumina HiSeq 2500 or NextSeq instrument.

Raw reads were processed as described elsewhere (Benjak et al., 2018). The phylogenetic analysis was performed using a concatenated SNP alignment (Supplementary Table S3). Maximum parsimony (MP) trees were constructed in MEGAX (Kumar et al., 2018) with the 72 new genomes from this study (Supplementary Table S2) and 170 previously published genomes (Supplementary Table S4; Honap et al., 2018; Schuenemann et al., 2018) using 500 bootstrap replicates and M. lepromatosis as an outgroup. Sites with missing data were partially deleted (arbitrary 80% coverage cutoff), resulting in 4,040 variable sites used for the tree calculation. Dating analyses were done using BEAST2 (v2.5.2) (Volz and Siveroni, 2018), as described previously (Benjak et al., 2018), with 234 genomes (Supplementary Table S5) and an increased chain length from 50 to 100 million. Briefly, the concatenated SNPs for each sample were used for tip dating analysis. Hypermutated strains and highly mutated genes associated with drug resistance were omitted, but sites with missing data as well as constant sites were included in the analysis, as previously described (Benjak et al., 2018). We included only unambiguous constant sites, i.e., loci where the reference base was called in all samples. Indel calling was done using Platypus v0.8.1 followed by manual curation (Rimmer et al., 2014).

Genome-Wide Comparison

The SNPs and indels of the newly sequenced genomes from Madagascar and Comoros were compared to the 170 previously published genomes (Supplementary Table S3) and the 72 new genomes from this study (Supplementary Table S2). The impact of amino acid substitutions on protein function was predicted using the online tool Provean (Choi and Chan, 2015).

M. leprae Enrichment of Libraries

To obtain enough M. leprae coverage, libraries from previously available DNA or DNA extracted using the total DNA extraction method (Supplementary Table S2) were target enriched for the M. leprae genome using a custom MYbaits Whole Genome Enrichment kit as described by Honap et al. (2018). Approximately 1.5 μg of each DNA library was captured and pooled with another library of a similar Ct prior to enrichment. Hybridization was performed at 65°C for 48 h. Each enrichment was followed by a second amplification step as per the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Results

Retrospective PCR Screening and WGS of Strains From Madagascar and the Comoros

Among the 51 patients included retrospectively in this study, 17 were female and 32 were male (two unknown), ranging from 2 to 75 years in age (Supplementary Table S1). They originated from 14 of the 22 regions in Madagascar and the Comoros; their origins are shown in Figure 1 (Supplementary Table S1). Four patients were considered as recurrent cases, and two samples (first and second episodes) were available for only one patient, 02018. Initially, 30 out of 60 samples showed PCR and/or ZN positivity (Supplementary Table S1), for which DNA was re-extracted using the HD method prior to whole-genome quenching characterization. Among the 30 ZN- and PCR-negative samples re-extracted using total DNA extraction, 17 were positive by RLEP PCR (Supplementary Table S1). A second biopsy was available for 11 of 17 positive samples and DNA was re-extracted using the HD method (Supplementary Table S1). The 13 samples negative for M. leprae by PCR were also negative for M. lepromatosis. Most of the patients with negative PCR and ZN results presented with tuberculoid or paucibacillary leprosy forms, which are characterized by a low amount of bacteria in the skin. Additionally, two negative cases were children and one patient was sampled during a reaction stage. In both cases, the amount of bacteria was also considered low. Finally, one sample was collected for differential diagnosis from a child; the negativity was interpreted as indicating an unrelated disease.

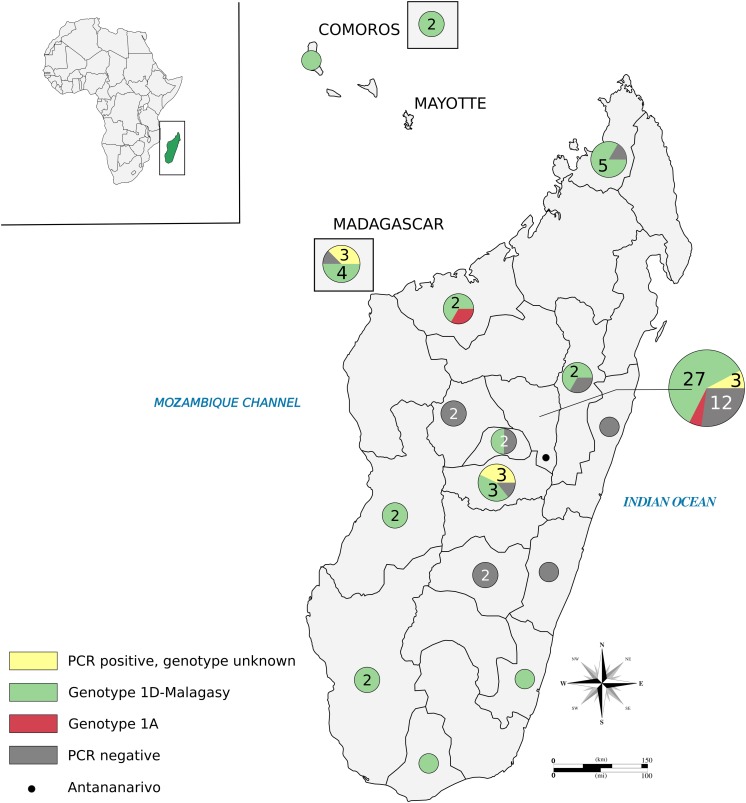

FIGURE 1.

Sampling sites in Madagascar and the Comoros. Pie charts indicate the regions where patients originated and are color-coded based on PCR and genotyping results, as indicated in the caption box. Numbers within circles represent different patients tested when there is more than one patient. Most of the samples were collected in Antananarivo State. Boxed circles refer to the eight patients of unknown location in the island. Data used for the map are available in Supplementary Tables S1, S2 (86 patients). Multiple samples derived from one patient are counted only once. The figure was drawn in Inkscape (Yuan et al., 2016). The map was downloaded from https://www.amcharts.com/svg-maps/ under a free license and modified for the current figure.

All 41 HD-extracted DNA samples were considered for WGS (Supplementary Table S1). Initial screening showed that efficient WGS (coverage > 5) was achieved in all cases for samples with a qPCR Ct < 28, while only two out of six genomes were recovered in samples with a Ct > 28 (Supplementary Table S1). Md09041 was initially positive by PCR following tDNA extraction, but was negative after HD extraction. For this reason, five samples with a Ct > 28 were not prepared for WGS (Supplementary Table S1). One library failed the quality controls after amplification and was not sequenced. All other DNA extracts (n = 35) were sent for library preparation and sequencing (Supplementary Table S2). Three DNA extracts from our 2005 study (Monot et al., 2005) presented Ct values between 17.5 and 28.1 by qPCR (Supplementary Table S1). Libraries were target-enriched using bait capture, but only the sequences of two strains, B191 and B204, met the inclusion criteria of coverage > 5 × (Supplementary Table S1).

Overall, a total of 33 genomes, from 27 patients (n = 30) from six regions of Madagascar and the Comoros (n = 3), were sequenced with more than 5 × average coverage of non-duplicated reads (Supplementary Tables S2, S6).

Genome-Wide Analysis of M. leprae Strains From Madagascar and the Comoros

Genotyping and Phylogeny

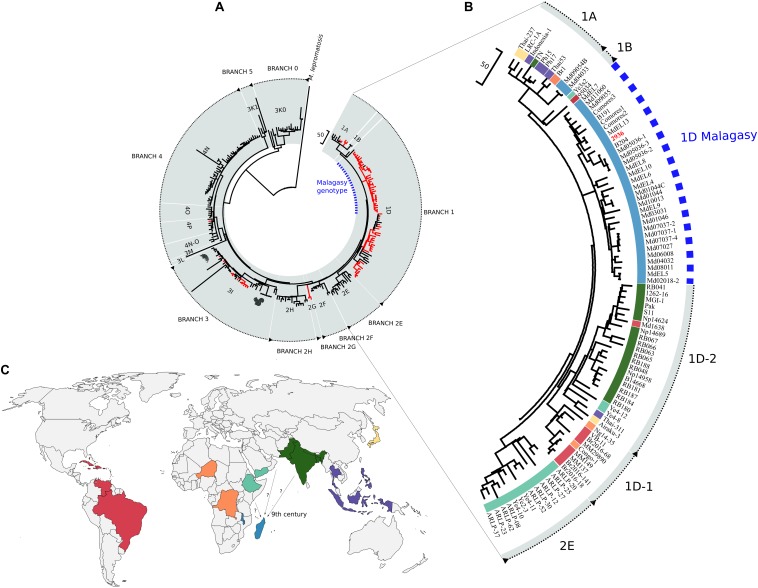

All the sequenced M. leprae strains from Madagascar and the Comoros belonged phylogenetically to branch 1 (Figure 2; Schuenemann et al., 2018). At the SNP subtype level, apart from two SNP subtype 1A, all other strains corresponded to the SNP type 1D (Monot et al., 2009; Benjak et al., 2018). Interestingly, SNP type 1D from Madagascar and the Comoros clustered with strain 2936, previously obtained from Malawi (Benjak et al., 2018), and together these formed a distinct clade that is closely related to the other SNP type 1D strains (Figure 2). The canonical SNP type 1D is composed of two monophyletic groups, including 1D strains from Asia on the one hand and strains from Africa and South America on the other (Figure 2), previously described as 1D-1 and 1D-2 genotypes, respectively (Singh et al., 2014). Branch 1 is now composed of the genotypes 1A, 1B, 1D, and the new 1D-Malagasy genotype.

FIGURE 2.

Phylogeography of Mycobacterium leprae strains. (A) Maximum parsimony tree of 241 genomes of M. leprae representing the nine branches and the 16 genotypes. Support values were obtained by bootstrapping 500 replicates. Branch lengths are proportional to nucleotide substitutions. The tree is rooted using Mycobacterium lepromatosis. The 1D-Malagasy genotype, discovered in this investigation, is shown in blue. Newly sequenced genomes are shown in red. (B) Zoom into branch 1 (genotypes 1A, 1B, 1D, and the 1D-Malagasy) and 2E of the maximum parsimony tree from (A). The 1D-Malagasy genotype is indicated with the dotted blue line and the strain from Malawi in bold red. (C) Global distribution of the genotypes from the branches 1 and 2E. Genotypes are colored as in (B). Strains from the canonical 1D are found in 12 countries, while the 1D-Malagasy is found only in Madagascar, the Comoros, and Malawi. The arrows indicate possible routes of leprosy introduction into Madagascar and Comoros with the estimated time frame.

Of all the 119 new samples from Madagascar (n = 30; Supplementary Table S1) and 10 other countries (n = 89; Supplementary Table S7) that were either whole-genome-sequenced or PCR-genotyped, the 1D-Malagasy genotype was restricted to Madagascar and the Comoros (30/119). The Malagasy genotype 1D is thus predominant in Madagascar, accounting for 97% of the strains present in 10 of the 14 regions in the country tested (Figure 1).

Aside from the Malagasy samples, 39 new M. leprae strains from eight countries, chosen for their proximity to Madagascar or based on the genotyping results previously obtained (Monot et al., 2009) or from this study, were sequenced, representing four different genotypes: 1D, 2G, 3I, and 4P (Supplementary Tables S2–S5). We report here the first whole-genome sequences of two genotype 2G strains, which cluster on a new branch in the phylogeny, falling between branches 2F and 2H (Figure 2).

Dating

The most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of all the M. leprae strains from branch 1 is estimated to be 2,315 years old [95% highest posterior density (HPD) of 1,903–2,798 ya] and was probably derived from a genotype 2 strain (Supplementary Figures S1, S2). The divergence time of the MRCA of the 1D and 1D-Malagasy strains is 2,270 ya (95% HPD = 1,870–2,744 ya). The divergence time of the MRCA of the 1D-Malagasy strains is 1,132 ya, i.e., the ninth century C.E. (95% HPD = 878–1,417 ya), whereas inside the genotype 1A, the two strains from Madagascar seem to have appeared more recently, around the late 17th century (95% HPD = 175–494 ya; median = 322 ya) (Supplementary Figure S2).

Genome-Wide Analysis of the 1D-Malagasy Genotype

From the genome-wide comparison of the 33 new strains from Madagascar and Comoros with 209 other M. leprae genomes, 18 polymorphisms were found only in the Malagasy 1D subtype (Supplementary Table S8), including two missense mutations in protein coding sequences. One occurs in ml0242 (16G > T, Val6Phe), encoding an essential enzyme of the isoprenoid biosynthesis pathway, IspE or 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase. The mutation was predicted to be deleterious for the protein function (PROVEAN score, −4.393). The other mutation was found at the end of ml2446 (1015 A > G, Asn339Asp) encoding lipoprotein Q, LprQ. This mutation was predicted to be neutral (PROVEAN score, −2.163).

Interestingly, in all 1D-Malagasy strains, a single nucleotide insertion affects the stop codon of ml1328 (1581156 G > GT; Ter453fs), coding for the proteasome accessory factor A, PafA. In M. leprae, as in M. tuberculosis, pafA is part of a transcriptional unit with ml1329 (pafB) and ml1330 (pafC) (Festa et al., 2007). Only six nucleotides separate pafA from pafB, while the stop codon of pafB overlaps the start codon of pafC. In M. tuberculosis, all three genes are co-transcribed, but not essential for growth (Festa et al., 2007). The insertion of a T before the pafA stop codon is predicted to lead to the production of a protein that is nine amino acids longer and to the loss of the pafB start codon.

Discussion

The African continent is home to multiple M. leprae genotypes, and this study brings additional complexity to the picture. In summary, branch 4 strains seem to be restricted to West Africa, whereas branches 2E, 2F, and 2H are present in East Africa, including Ethiopia (2E, 2F, and 2H) and Malawi (2E) (Monot et al., 2009; Benjak et al., 2018). Strains from branches 1 and 2 have been reported in the Congo (Reibel et al., 2015), while branch 3 strains, notably of genotype 3I, have been described in Morocco and Egypt (Monot et al., 2009). The canonical SNP type 1D is found in 12 countries outside Africa (Monot et al., 2009; Benjak et al., 2018). In Africa, a single 1D strain was found in Niger (Benjak et al., 2018), and one was found in the Congo in this study. The new 1D-Malagasy genotype is prevalent in Madagascar and the Comoros. The only other genome available from Southeast Africa, Malawi (Benjak et al., 2018), also belongs to the 1D-Malagasy genotype. Monot et al. (2009) reported the presence of the genotypes 1D and 2E in Malawi using the standard genotyping system, but more screening will be necessary to establish the frequency of the 1D-Malagasy genotype in the country and elsewhere on the continent. The most ancestral lineage of M. leprae, branch 0 (Schuenemann et al., 2018), has not been reported in Africa. Altogether, these data suggest that human migrations have mainly contributed to the introduction of different M. leprae genotypes from elsewhere.

The first record of humans in Madagascar is from the beginning of the first millennium with the arrival of Austronesians from the Sunda Islands, ∼4,000 mi. to the East of Madagascar (Dewar and Wright, 1993; Pierron et al., 2014, 2017). The permanent residential settlement of inhabitants in Madagascar is estimated at 700 C.E., with a colonization wave of Austronesians from East Asia and by the Bantu from East Africa (Pierron et al., 2014; Crowther et al., 2016). This also coincides with the entry of East Africa into the Indian Ocean trade, connecting the continent with Asia and the Middle East around 800 C.E. (Seland, 2013; Lawler, 2014; Crowther et al., 2016). An additional migration wave was observed between 1,000 and 1,500 C.E., with individuals of Austronesian, Bantu, and Middle Eastern origins (Pierron et al., 2014). The M. leprae SNP type 1A, found at a very low frequency (3%) in Madagascar, is mostly reported in Southeast Asia (Philippines and Indonesia, 90 and 60%, respectively), North India and Nepal (2%), Thailand (one strain), Korea (50%), and Bangladesh (50%) (Monot et al., 2009).

Our data suggest that the subtype 1A was introduced into Madagascar and Comoros after East Africa entered the Indian trade route around 800 C.E., or when the East India Company began the slave trade with Madagascar in the 17th century (Thomas, 2014). The MRCA of the 1D-Malagasy genotype was likely a SNP type 2 strain, which was circulating in medieval Europe and is currently prevalent in East Africa and the Middle East. The MRCAs of the canonical 1D and the 1D-Malagasy strains further suggest an introduction of the 1D-Malagasy genotype between the third century B.C.E and ninth century C.E. The 1D-Malagasy genotype was found in 10 regions in Madagascar and in three different countries (Madagascar, Comoros, and Malawi). The 1D-Malagasy clade is composed of several monophyletic groups. We anticipate that most of the genetic diversity for this genotype has been captured during this investigation, suggesting that the strain was introduced into Madagascar and the Comoros no earlier than the ninth century C.E. Besides, the estimates of our model overlap with the previous estimates reported by Schuenemann et al. (2018), with the MRCA of branch 1 being 2,248 years old vs. 2,315 years old in our study. Altogether, these data rule out Austronesian migrations as the origin of the 1D-Malagasy M. leprae genotype found in Madagascar and, rather, point to an introduction from East Africa, the Middle East, or South Asia around the time of the Indian Ocean trade (Lawler, 2014). However, the exact origin of the 1D-Malagasy genotype is difficult to pinpoint due to the near-complete absence of genomic information from the neighboring countries or countries where the canonical 1D genotype was previously reported, like India and the Middle East (Monot et al., 2009; Lavania et al., 2015). The sole exception is strain 2936 from Malawi, which is highly related to four isolates from Madagascar (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figures S2, S3). Furthermore, yet another argument against the Austronesian origin of leprosy in Madagascar is the relatively young age of the 1A genotype, which is the prevalent genotype in Southeast Asia (Phetsuksiri et al., 2012). Nevertheless, additional investigation using the specific 1D-Malagasy marker on the islands, in surrounding countries, and those where genotype 1D occurs should help to retrace the exact origin of the 1D-Malagasy genotype and obtain a full picture of the strain’s diversity.

There is a strikingly low strain diversity in Madagascar and the Comoros compared to other islands such as New Caledonia or the Antilles (Monot et al., 2009), where several different genotypes have been observed. This is consistent with the relative isolation of the Malagasy population and the lower immigration into Madagascar in the last centuries compared to other islands or oceanic regions located on major routes of trade or migration.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA592722.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out under the ethical consent of the WHO Global Leprosy Programme surveillance network. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author Contributions

CA, SC, MR-A, J-LB, and EC designed the study. LR, FRR, BC, AC DD, RN, AA, FS, and AR collected the samples for this study. JS, MM, AG, CS, AA, and VJ collected the samples as part of other ongoing studies. CA, EL, FAR, PS, MT-C, TL-C, and TR performed DNA extraction, molecular screening, and WGS. SB-R and PB, and PS performed PCR sequencing. CA, AB, MR-A, and SC processed the experimental data. CA and AB performed the computational analysis. CA, AB, SC, EL, and EC drafted the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the patients and clinical staff who participated in the study. We thank Bastien Mangeat, Elisa Cora, and the team from the Gene Expression Core Facility at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne for Illumina sequencing and technical support as well as Emmanuel Baudoing and Johann Weber from the Lausanne Genomic Technologies Facility at Lausanne University. Thanks to Julia Rochard Libois and Christelle Koebel for sending samples to the Centre National de Référence des Mycobactéries et de la résistance des Mycobactéries aux Antituberculeux and Marc Monot for conserving the DNA samples from GMB, Institut Pasteur. We thank the technicians of the CNR-MyRMA. We thank the TLMIB staff (Rural Health Programme) for recruitment and sample collection in Bangladesh and Prof. Mary Jackson for her critical review of the manuscript. The following reagent was obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: Genomic DNA from Mycobacterium leprae, Strain Thai-53, NR-19352.

Funding. This work was supported by the Fondation Raoul Follereau (SC), the Fondation AnBer (FAR), the Fondation Mérieux Lyon (MR-A), the Swiss National Science Foundation Grants IZRJZ3_164174 (SC) and P2ELP3_184476 (CA), the Heiser Program of the New York Community Trust for Research in Leprosy Grant Nos. P15-000827, P16-000976 and P18-000250 (JS, CS, MM, CA and SC), a Fulbright Scholar to Brazil award 2019–2020 (JS), CNPq fellowships Grant Nos. 428964/2016-8 and 313633/2018-5, CAPES PROAMAZONIA 3288/2013, and Brazil Ministry of Health 035527/2017 (CS), the Association de Chimiothérapie Anti-Infectieuse of the Société Française de Microbiologie, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant No. 845479 (CA), the Q.M. Gastmann-Wichers Foundation (AG) and the R2STOP Research grant from effect:hope Canada and The Mission to End Leprosy, Ireland (AG, PS), and Leprosy Research Initiative Netherlands (PS). The CNR-MyRMA receives an annual grant from Santé Publique France (EL, EC). CA was also supported by a non-stipendiary European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) long-term fellowship (ALTF 1086-2018). PS was a recipient of the Ramalingaswami Fellowship from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00711/full#supplementary-material

References

- Avanzi C., Del-Pozo J., Benjak A., Stevenson K., Simpson V. R., Busso P., et al. (2016). Red squirrels in the British Isles are infected with leprosy bacilli. Science 354 744–747. 10.1126/science.aah3783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjak A., Avanzi C., Singh P., Loiseau C., Girma S., Busso P., et al. (2018). Phylogenomics and antimicrobial resistance of the leprosy bacillus Mycobacterium leprae. Nat. Commun. 9:352. 10.1038/s41467-017-02576-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burney D. A., Burney L. P., Godfrey L. R., Jungers W. L., Goodman S. M., Wright H. T., et al. (2004). A chronology for late prehistoric Madagascar. J. Hum. Evol. 47 25–63. 10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambau E., Saunderson P., Matsuoka M., Cole S. T., Kai M., Suffys P., et al. (2018). Antimicrobial resistance in leprosy: results of the first prospective open survey conducted by a WHO surveillance network for the period 2009-15. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 24 1305–1310. 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y., Chan A. P. (2015). PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinform. Oxf. Engl. 31 2745–2747. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther A., Lucas L., Helm R., Horton M., Shipton C., Wright H. T., et al. (2016). Ancient crops provide first archaeological signature of the westward Austronesian expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 6635–6640. 10.1073/pnas.1522714113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar R. E., Wright H. T. (1993). The culture history of Madagascar. J. World Prehistory 7 417–466. 10.1007/BF00997802 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Festa R. A., Pearce M. J., Darwin K. H. (2007). Characterization of the Proteasome Accessory Factor (paf) Operon in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 189 3044–3050. 10.1128/JB.01597-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girma S., Avanzi C., Bobosha K., Desta K., Idriss M. H., Busso P., et al. (2018). Evaluation of Auramine O staining and conventional PCR for leprosy diagnosis: a comparative cross-sectional study from Ethiopia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12:e0006706. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X. Y., Seo Y.-H., Sizer K. C., Schoberle T., May G. S., Spencer J. S., et al. (2008). A new Mycobacterium species causing diffuse lepromatous leprosy. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 130 856–864. 10.1309/AJCPP72FJZZRRVMM [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasker E., Baco A., Younoussa A., Mzembaba A., Grillone S., Demeulenaere T., et al. (2017). Leprosy on Anjouan (Comoros): persistent hyper-endemicity despite decades of solid control efforts. Lepr. Rev. 88 334–342. [Google Scholar]

- Honap T. P., Pfister L.-A., Housman G., Mills S., Tarara R. P., Suzuki K., et al. (2018). Mycobacterium leprae genomes from naturally infected nonhuman primates. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12:e0006190. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insitute of Medicine (2010). “Migration, mobility and health,” in Infectious Disease Movement in a Bordeless World, Ed. Mack A. (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. (2018). MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35 1547–1549. 10.1093/molbev/msy096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavania M., Jadhav R., Turankar R. P., Singh I., Nigam A., Sengupta U. (2015). Genotyping of Mycobacterium leprae strains from a region of high endemic leprosy prevalence in India. Infect. Genet. Evol. 36 256–261. 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler A. (2014). Sailing Sinbad’s seas. Science 344 1440–1445. 10.1126/science.344.6191.1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monot M., Honoré N., Garnier T., Araoz R., Coppée J.-Y., Lacroix C., et al. (2005). On the origin of leprosy. Science 308 1040–1042. 10.1126/science/1109759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monot M., Honoré N., Garnier T., Zidane N., Sherafi D., Paniz-Mondolfi A., et al. (2009). Comparative genomic and phylogeographic analysis of Mycobacterium leprae. Nat. Genet. 41 1282–1289. 10.1038/ng.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortuno-Gutierrez N., Baco A., Braet S., Younoussa A., Mzembaba A., Salim Z., et al. (2019). Clustering of leprosy beyond the household level in a highly endemic setting on the Comoros, an observational study. BMC Infect. Dis. 19:501. 10.1186/s12879-019-4116-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phetsuksiri B., Srisungngam S., Rudeeaneksin J., Bunchoo S., Lukebua A., Wongtrungkapun R., et al. (2012). SNP genotypes of Mycobacterium leprae isolates in Thailand and their combination with rpoT and TTC genotyping for analysis of leprosy distribution and transmission. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 65 52–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierron D., Heiske M., Razafindrazaka H., Rakoto I., Rabetokotany N., Ravololomanga B., et al. (2017). Genomic landscape of human diversity across Madagascar. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 E6498–E6506. 10.1073/pnas.1704906114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierron D., Razafindrazaka H., Pagani L., Ricaut F.-X., Antao T., Capredon M., et al. (2014). Genome-wide evidence of Austronesian–Bantu admixture and cultural reversion in a hunter-gatherer group of Madagascar. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 936–941. 10.1073/pnas.1321860111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raharolahy O., Ramarozatovo L. S., Ranaivo I. M., Sendrasoa F. A., Andrianarison M., Andrianarivelo M. R., et al. (2016). A case of fluoroquinolone-resistant leprosy discovered after 9 years of Misdiagnosis. Case Rep. Infect. Dis. 2016:4632369. 10.1155/2016/4632369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratsimbaharison A., Ellis S. (2010). Madagascar: A Short History. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reibel F., Chauffour A., Brossier F., Jarlier V., Cambau E., Aubry A. (2015). New insights into the geographic distribution of Mycobacterium leprae SNP genotypes determined for isolates from Leprosy cases diagnosed in Metropolitan France and French Territories. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9:e0004141. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimmer A., Phan H., Mathieson I., Iqbal Z., Twigg S. R. F., Wgs500 Consortium et al. (2014). Integrating mapping-, assembly- and haplotype-based approaches for calling variants in clinical sequencing applications. Nat. Genet. 46 912–918. 10.1038/ng.3036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuenemann V. J., Avanzi C., Krause-Kyora B., Seitz A., Herbig A., Inskip S., et al. (2018). Ancient genomes reveal a high diversity of Mycobacterium leprae in medieval Europe. PLoS Pathog. 14:e1006997. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuenemann V. J., Singh P., Mendum T. A., Krause-Kyora B., Jäger G., Bos K. I., et al. (2013). Genome-wide comparison of medieval and modern Mycobacterium leprae. Science 341 179–183. 10.1126/science.1238286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seland E. H. (2013). Networks and social cohesion in ancient Indian Ocean trade: geography, ethnicity, religion. J. Glob. Hist. 8 373–390. 10.1017/S1740022813000338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P., Benjak A., Carat S., Kai M., Busso P., Avanzi C., et al. (2014). Genome-wide re-sequencing of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium leprae Airaku-3. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20 O619–O622. 10.1111/1469-0691.12609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P., Benjak A., Schuenemann V. J., Herbig A., Avanzi C., Busso P., et al. (2015). Insight into the evolution and origin of leprosy bacilli from the genome sequence of Mycobacterium lepromatosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 4459–4464. 10.1073/pnas.1421504112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttels V., Lenaerts T. (2016). Epidemiology and spatial exploratory analysis of leprosy in the district of Toliara, Madagascar. Lepr. Rev. 87 305–313. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. H. (2014). Merchants and maritime marauders: the East India compagny and the problem of piracy in the eighteenth century. Gt. Circ. 36 83–107. [Google Scholar]

- Tió-Coma M., Avanzi C., Verhard E. M., Pierneef L., Hooij A., van Benjak A., et al. (2020). Detection of new Mycobacterium leprae subtype in Bangladesh by genomic characterization to explore transmission patterns. medRxiv 10.1101/2020.03.05.20031450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tió-Coma M., Wijnands T., Pierneef L., Schilling A. K., Alam K., Roy J. C., et al. (2019). Detection of Mycobacterium leprae DNA in soil: multiple needles in the haystack. Sci. Rep. 9:3165. 10.1038/s41598-019-39746-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truman R. W., Andrews P. K., Robbins N. Y., Adams L. B., Krahenbuhl J. L., Gillis T. P. (2008). Enumeration of Mycobacterium leprae Using Real-Time PCR. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2:e328. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz E. M., Siveroni I. (2018). Bayesian phylodynamic inference with complex models. PLoS Comput. Biol. 14:e1006546. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO SEARO/Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases (2017). A Guide for Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Leprosy: 2017 Update. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2019). Global Leprosy Update, 2018: Moving Towards a Leprosy- Free World. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Woods S. A., Cole S. T. (1989). A rapid method for the detection of potentially viable Mycobacterium leprae in human biopsies: a novel application of PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 53 305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Chan H. C. S., Filipek S., Vogel H. (2016). PyMOL and inkscape bridge the data and the data visualization. Struct. Lond. Engl. 1993 2041–2042. 10.1016/j.str.2016.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA592722.