Abstract

Home infusion therapy can provide a safer alternative for exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection for many vulnerable patients who receive parenteral therapies on an outpatient basis, such as parenteral antimicrobial therapy. This article proposes changes to Medicare payment policy, which currently does not adequately reimburse for these services for many patients.

In December 2019, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) started an epidemic in Wuhan, China, that has since spread throughout the world. Now called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the illness caused by SARS-CoV-2 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on 11 March 2020. Reports from China showed that older age is a significant risk factor for morbidity and mortality among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 (1). In Washington state, an initial epicenter of COVID-19 in the United States, nursing home residents were one of the most heavily affected populations and had high mortality rates, highlighting COVID-19's ability to spread rapidly in such settings (2). Other risk factors for worse outcomes include an immunocompromised state, underlying structural lung disease, cardiac disease, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes (3).

Each of these comorbid conditions is common in persons receiving outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT), making this group a high-risk population. However, current payment policy under Medicare could lead to unintended consequences for patients receiving OPAT, including exposure to COVID-19.

Home Infusion Therapy and Medicare Policy

Home infusion involves the intravenous administration of medications at home. For patients to receive home infusions, several components need to be covered: the medication itself, the supplies and equipment, and the services of the home visit nurse. Many conditions require intravenous administration of medication at home, including total parenteral nutrition, intravenous antibiotics, and intravenous immunoglobulins.

Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy is one of the most common home infusion services and has been used for 4 decades (4). It has been shown to be a convenient and cost-effective way to complete prolonged courses of intravenous antibiotics outside the hospital (5). It and other outpatient intravenous medications can be given in various settings, including at home with the assistance of home health, at outpatient infusion centers, or at skilled-nursing facilities. Most private insurance and Medicare Advantage plans, Tricare, and many state Medicaid programs cover home infusion services, and it is the most commonly used model among these beneficiary groups as a result (6).

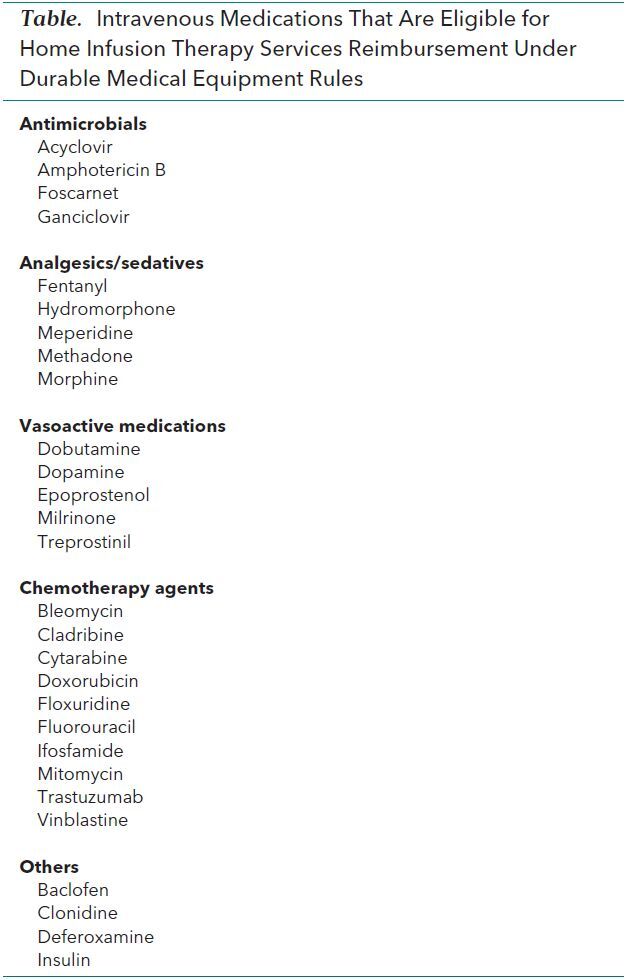

However, the Medicare fee-for-service program does not adequately cover infusion services provided in patients' homes. Although Medicare Part A covers home nursing, it does so only for patients who are homebound, which many patients in need of home infusion services are not. Medicare Part B covers a few intravenous medications under payment rules about durable medical equipment, but these represent fewer than 10% of antimicrobials prescribed for OPAT (Table) (7). Medicare Part D, used by 70% of Medicare beneficiaries, does cover most of the drugs but not the medically necessary supplies—tubing, bags, needles, and pumps—or the administrative, pharmacy, and nursing services needed to deliver the medication (8).

Table. Intravenous Medications That Are Eligible for Home Infusion Therapy Services Reimbursement Under Durable Medical Equipment Rules.

Patients who choose home infusion services are often left with significant costs that can be prohibitively expensive to pay out of pocket. Therefore, these policies incent patients to go to outpatient infusion centers or be admitted to skilled-nursing facilities to get their OPAT courses covered (9). Consequently, many patients go to skilled-nursing facilities for the sole purpose of receiving intravenous antibiotics without any other needs for skilled care. This has been shown to increase health care costs compared with receipt of OPAT at home (9).

The Need to Shift Care to Home

As we try to hamper the spread of COVID-19, efforts should be made to limit patients' interactions with health care facilities where patients with COVID-19 are likely to be. This is especially important for the elderly population and patients who are immunocompromised, and it includes limiting or eliminating contact with all health care facilities as feasible. Outpatient infusion centers are located on hospital campuses or in physicians' offices, where patients coming for infusions could come into contact with patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. The risk is higher for those receiving OPAT because they are required to come daily—and in some cases twice daily—leading to repeated exposure. Nursing homes can subject patients to even higher risk for SARS-CoV-2 exposure, with catastrophic results: In some states, almost half of nursing home residents have been infected. In addition, frequent contacts with the health care system will put patients receiving infusion therapy at risk for other nosocomial infections, such as with multidrug-resistant organisms, Clostridium difficile, or other respiratory viruses.

Furthermore, because we expect more cases of COVID-19 to flood the health care system, transitioning OPAT to the home setting can free nursing home beds. This would allow hospitals to discharge stable patients to nursing facilities and thus would expand the capacity of the health care system to care for more acutely ill patients. Transitioning patients receiving OPAT to home would also help conserve personal protective equipment among health care workers, which is critical given the national shortage in supplies.

A Need for Urgent Medicare Policy Change

Because the Medicare patient population mostly consists of persons older than 65 years, the group in which nearly 80% of deaths have occurred thus far, it comprises some of the highest-risk patients for COVID-19 (10). We urge the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to issue an immediate policy change to allow reimbursement for the supplies, as well as the administrative, pharmacy, and nursing services, needed to provide home infusion therapy. There have previously been concerns that expanding coverage for OPAT will lead to increased unnecessary use of intravenous antibiotics. However, this can be overcome by limiting OPAT coverage to the diagnoses that are treated with intravenous antibiotics in standard clinical care, such as endocarditis and osteomyelitis.

Such a change will need to include allowance of reimbursement for physicians supervising the plan of care, home infusion pharmacy, and home health services. Under the current declared state of emergency, this policy change can be authorized by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services without the need for congressional approval, similar to the temporarily expanded coverage of telehealth services, and thus could be done expeditiously. If this were done in conjunction with telehealth, it could lead to protection of both patients and health care providers. We urge the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to take timely action to avoid subjecting Medicare beneficiaries to unnecessary and potentially catastrophic exposure to COVID-19.

Biography

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Financial Support: Dr. Joynt Maddox receives research support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL143421) and National Institute on Aging (R01AG060935). Dr. Powderly was supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002345 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures: Disclosures can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M20-1774.

Corresponding Author: Yasir Hamad, MD, Campus Box 8051, 4523 Clayton Avenue, St. Louis, MO 63110; e-mail, yhamad@wustl.edu.

Current Author Addresses: Drs. Hamad and Powderly: Campus Box 8051, 4523 Clayton Avenue, St. Louis, MO 63110.

Dr. Joynt Maddox: Campus Box 8217, 660 South Euclid Avenue, St. Louis, MO 63110.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: Y. Hamad, K.E. Joynt Maddox, W.G. Powderly.

Drafting of the article: Y. Hamad.

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: K.E. Joynt Maddox, W.G. Powderly.

Final approval of the article: Y. Hamad, K.E. Joynt Maddox, W.G. Powderly.

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 13 May 2020.

References

- 1. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020. [PMID: 32167524] doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington state. JAMA. 2020. [PMID: 32191259] doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim clinical guidance for management of patients with confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/index.html. on 1 May 2020.

- 4. Rucker RW, Harrison GM. Outpatient intravenous medications in the management of cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 1974;54:358-60. [PMID: 4213282] [PubMed]

- 5. doi: 10.1086/653520. Paladino JA, Poretz D. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy today. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51 Suppl 2:S198-208. [PMID: 20731577] doi:10.1086/653520. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz363. Hamad Y, Lane MA, Beekmann SE, et al. Perspectives of United States–based infectious diseases physicians on outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy practice. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6. [PMID: 31429872] doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7. doi: 10.1002/phar.2099. Keller SC, Dzintars K, Gorski LA, et al. Antimicrobial agents and catheter complications in outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38:476-481. [PMID: 29493791] doi:10.1002/phar.2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. Cubanski J, Damico A, Neuman T. 10 things to know about Medicare Part D coverage and costs in 2019. 4 June 2019. Accessed at www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/10-things-to-know-about-medicare-part-d-coverage-and-costs-in-2019. on 1 May 2020.

- 9. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ750. Keller S, Pronovost P, Cosgrove S. What Medicare is missing [Letter]. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1890-1. [PMID: 26338782] doi:10.1093/cid/civ750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Health Statistics. Provisional death counts for coronavirus disease (COVID-19): weekly updates by select demographic and geographic characteristics. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid_weekly/index.htm. on 1 May 2020.