Abstract

Sexual contact carries some risk for exposure to infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. This commentary provides clinicians with guidance on how to address sexual health and activity with patients in this context.

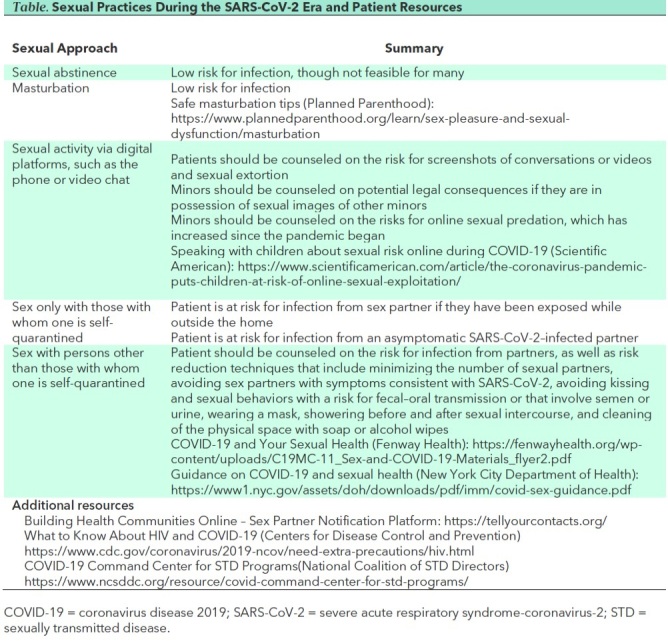

More than 200 000 people have died of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, leading to widespread concern regarding physical morbidity and mortality. The sexual health implications, however, have received little focus. On the basis of existing data, it appears all forms of in-person sexual contact carry risk for viral transmission, because the virus is readily transmitted by aerosols and fomites. This has resulted in broad guidance regarding physical distancing, with substantial implications for sexual well-being. Given the important role of sexuality in most people's lives, health care providers (HCPs) should consider counseling patients on this topic whenever possible. This is an unprecedented and stressful time for HCPs; facilitating brief conversations and referrals to relevant resources (Table) can help patients maintain sexual wellness amid the pandemic.

Table. Sexual Practices During the SARS-CoV-2 Era and Patient Resources.

Current Evidence Suggests That All In-person Sexual Contact Carries Transmission Risk

SARS-CoV-2 is present in respiratory secretions and spreads through aerosolized particles (1). It may remain stable on surfaces for days (1). On the basis of this information, all types of in-person sexual activity probably carry risk for SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Infected individuals have the potential to spread respiratory secretions onto their skin and personal objects, from which the virus can be transmitted to a sexual partner. Because many SARS-CoV-2–infected people are asymptomatic, HCPs are left with little to offer beyond guidance to not engage in any in-person sexual activity.

Data are lacking regarding other routes of sexual transmission. Two small studies of SARS-CoV-2–infected people did not detect virus in semen or vaginal secretions (2, 3). An additional study of semen samples from 38 patients detected the virus by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction in 6 patients (15.8%) (4). However, the relevance regarding sexual transmission remains unknown. Until this is better understood, it would be prudent to consider semen potentially infectious. Although 1 study failed to detect the virus in urine samples (5), there is evidence that SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acids were detected in a urine sample in at least 1 patient in another study (6). Until this is clarified, urine should also be considered potentially infectious. SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been detected in stool samples, raising concern for fecal–oral transmission (7). It is not clear, however, whether viral RNA detected in stool is capable of causing productive infection. Moreover, these data are moot, given that any in-person contact results in substantial risk for disease transmission owing to the virus' stability on common surfaces and propensity to propagate in the oropharynx and respiratory tract.

Psychological Effects of Sexual Abstinence

Sexual expression is a central aspect of human health but is often neglected by HCPs. Messaging around sex being dangerous may have insidious psychological effects at a time when people are especially susceptible to mental health difficulties. Some groups, including sexual and gender minority (SGM) communities, may be particularly vulnerable to sexual stigma, given the historical trauma of other pandemics, such as AIDS. Abstinence recommendations may conjure memories of the widespread stigmatization of SGM people during the AIDS crisis. For the population at large, a recommendation of long-term sexual abstinence is unlikely to be effective, given the well-documented failures of abstinence-based public health interventions and their likelihood to promote shame (8).

HCPs Should Consider Counseling on Safe Sexual Practices and Risk Reduction Whenever Possible

A range of sexual practices organized from least to most risky is shown in the Table. Abstinence is the lowest-risk approach to sexual health during the pandemic. Masturbation is an additional safe recommendation for patients to meet their sexual needs without the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Given that abstinence-only recommendations, however, are likely to promote shame and unlikely to achieve intended behavioral outcomes (8), sex-positive recommendations regarding remote sexual activity are optimal during the pandemic, balancing human needs for intimacy with personal safety and pandemic control. Patients can be counseled to engage in sexual activity with partners via the telephone or video chat services. Given privacy concerns, they should be counseled to use secure encrypted platforms. They should also be warned about the risks for sexual partners taking screenshots of conversations and relevant risks and laws regarding sexual extortion. For some patients, including those without internet access and minors at home from school who are in environments unaccepting of their sexual orientation, digital sexual practices may not be feasible. During all conversations, HCPs should express a nonjudgmental stance to encourage comfortable discussion and minimize shame. This is particularly important with minors, because fear of judgment can lead them to withhold information about sexual risk behaviors.

For some patients, complete abstinence from in-person sexual activity is not an achievable goal. In these situations, having sex with persons with whom they are self-quarantining is the safest approach. Those unable to take this approach may benefit from risk reduction counseling (Table), which has proven effective in other realms of sexual health (9). Patients should also be provided with information about how to reduce the risk for other sexually transmitted infections as well as the importance of continued use of contraceptives during this time to prevent unwanted pregnancy. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have released special guidance regarding SARS-CoV-2 and HIV (10). Those taking HIV preexposure prophylaxis should be encouraged to continue taking this medication consistently (10).

Looking to the Future

For the foreseeable future, HCPs will need to incorporate new technological advances regarding SARS-CoV-2 into how they think about sexual health and risk. As was seen during the HIV epidemic, antibody tests may play a key role in how we evaluate sexual risk. Though we currently lack data on how long such immunity may last, those who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies could have relative immunity to the virus. This may allow for the serosorting of individuals for sexual activity, with those testing positive for anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies presumed safe to engage in sex together with regard to SARS-CoV-2 transmission, if not for HIV or other sexually transmitted infections. Further research is needed to know if this will be an effective strategy. It will be important for HCPs to proactively discuss with patients what we learn from the emerging science: how reliable the antibody tests are, and to what extent these tests can inform SARS-CoV-2 risk assessment.

As we continue to fight the pandemic, researchers and HCPs ought to keep human sexuality in mind as an important aspect of health and counsel patients whenever possible. Public health officials must continue to disseminate accurate sexual health information. We need to collect more data on the risks related to SARS-CoV-2 transmission through intimate contact, best practices in sexual counseling, and optimal approaches for risk reduction.

Biography

Disclosures: Disclosures can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M20-2004.

Corresponding Author: Jack Turban, MD, MHS, Massachusetts General Hospital, 15 Parkman Street, WAC 812, Boston, MA 02114; e-mail, jack.turban@mgh.harvard.edu.

Current author addresses and author contributions are available at Annals.org.

Current Author Addresses: Dr. Turban: Jack Turban, MD, MHS, Massachusetts General Hospital, 15 Parkman Street, WAC 812, Boston, MA 02114.

Dr. Keuroghlian: Massachusetts General Hospital, Wang Building, 8th Floor, Boston, MA 02114.

Dr. Mayer: Fenway Health, 7 Haviland Street, Boston, MA 02115.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: J.L. Turban, A. Keuroghlian, K.H. Mayer.

Analysis and interpretation of the data: J.L. Turban.

Drafting of the article: A. Keuroghlian, J.L. Turban.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: J.L. Turban, A. Keuroghlian, K.H. Mayer.

Final approval of the article: J.L. Turban, A. Keuroghlian, K.H. Mayer.

Obtaining of funding: J.L. Turban.

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: A. Keuroghlian.

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 8 May 2020.

References

- 1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1 [Letter]. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564-1567. [PMID: 32182409] doi:10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.04.024. Pan F, Xiao X, Guo J, et al. No evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in semen of males recovering from COVID-19. Fertil Steril. 2020. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa375. Qiu L, Liu X, Xiao M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not detectable in the vaginal fluid of women with severe COVID-19 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [PMID: 32241022] doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8292. Li D, Jin M, Bao P, et al. Clinical characteristics and results of semen tests among men with coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e208292. [PMID: 32379329] doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020. [PMID: 32159775] doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005203. Guan WJ, Zhong NS. Clinical characteristics of covid-19 in China. reply [Letter]. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1861-1862. [PMID: 32220206] doi:10.1056/NEJMc2005203. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25825. Chen Y, Chen L, Deng Q, et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020. [PMID: 32243607] doi:10.1002/jmv.25825. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3282efdc0b. Ott MA, Santelli JS. Abstinence and abstinence-only education. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:446-52. [PMID: 17885460] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052835. Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Kalichman MO, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a sexual risk reduction intervention for STI prevention among men who have sex with men in the USA. Sex Transm Infect. 2018;94:40-45. [PMID: 28404766] doi:10.1136/sextrans-2016-052835. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What to know about HIV and COVID-19. 2020. 18 March 2020. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/hiv.html. on 5 May 2020.