Abstract

Background:

Integrins are the major cell adhesion receptors expressed in almost all cell types connecting the extracellular matrix with cell cytoskeletons and transducing bi-directional signals across cell membranes. In the central nervous system (CNS), integrins are pivotal for CNS cell migration, differentiation, neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis in both physiological and pathological conditions. Here we studied the effect of different integrin biding peptides for growth and development of primary cortical neurons in vitro.

New method:

Rat primary cortical neurons were cultured in an integrin-binding array platform, which contains immobilized varying short synthetic peptides that bind to 16 individual types of integrin on a 48-well cell culture plate. After cultured for 7 days, cells were fixed and processed for immunostaining with neuronal markers. The overall neuronal growth and neurite outgrowths were quantified.

Results:

We found that binding peptides for integrin αvβ8, α5β1 and α3β1 particularly the former two provided superior condition for neuronal growth, survival and maturation. Moreover, optimal neurite outgrowth was observed when neurons were cultured in 3-dimension using injectable hydrogel along with binding peptide for αvβ8 or α5β1 integrins.

Comparison with existing method:

For primary neuronal culture, poly-D-lysine coating is conventional method to support cell attachment. Our study has demonstrated that selected integrin binding peptides provide greater support for the growth of cultured primary neurons.

Conclusion:

These data suggest that integrin αvβ8 and α5β1 are conducive for survival, growth and maturation of primary cortical neurons. This information could be utilized in designing combinational biomaterial and cell-based therapy for neural regeneration following brain injury.

Keywords: Integrin, integrin-binding array, primary cortical neurons, neurite outgrowth, 3-D culture, hydrogels

1. Introduction

Integrins are the major type of transmembrane cell adhesion proteins that mediate cell binding to other cells as well as to the extracellular matrix. The integrin family of proteins consists of two non-covalently associated transmembrane glycoprotein subunits, i.e., α and β, leading to the formation of transmembrane heterodimers (Hynes 2002). Different combinations of α- and β- subunits give rise to different types of integrins. The majority of human integrin heterodimers are formed from 8 types of β-subunits and 18 types of α-subunits (Van der Flier and Sonnenberg 2001, Takada, Ye et al. 2007). To date, 20 types of integrins are found on almost all vertebrate cells (De Arcangelis and Georges-Labouesse 2000). Among them, 12 integrins contain the β1 subunit, and 5 contain αv. The types of integrins that are expressed on cell surfaces may determine their ligand-binding specificity. In addition, the ligand-binding property of an integrin may be influenced by cell-type-specific factors since the same type of integrin that is expressed in different cell types may exhibit different ligand-binding specificities (Plow, Haas et al. 2000, Van der Flier and Sonnenberg 2001, Humphries, Byron et al. 2006). Integrin binding to its ligands may be further mediated by extracellular divalent cations such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Mould, Akiyama et al. 1995, Oxvig and Springer 1998). Multiple types of integrins may bind to the same type of ECM protein, suggesting the diversity in integrin binding. Since integrin-ligand binding is the major mediator of cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions, it plays important roles on cell functions such as survival (for anchorage-dependent cells), proliferation, differentiation, and protein expression (Bokel and Brown 2002, Seebeck, Marz et al. 2017). Instead of only attaching cells to their surroundings, integrin-binding may trigger intracellular signaling pathways that are crucial for cell functions and response to the environment (Hynes 2002, Milner and Campbell 2002).

Despite the general knowledge about integrin binding, the platform to characterize the integrin expression profile and their ligand-binding properties on a particular cell type does not exist. Such characterization may serve the basis to design biomaterial surfaces or culture substrates to direct cell functions that are required for specific applications. For example, to promote biomaterial-assisted brain tissue regeneration in animal models of traumatic brain injury (TBI), the ligand profile of the biomaterial necessary to support the binding, survival, and growth of rat primary cortical neurons needs to be defined. Studies have shown that selective exclusion of integrins and other growth-related molecules from mature CNS axons is the main reason for the loss of regenerative ability with maturity (Franssen, Zhao et al. 2015). Moreover, integrin levels increase significantly after nerve injuries (Nieuwenhuis, Haenzi et al. 2018). To date, published studies have revealed the presence of integrins α5β1 and αvβ8 on rat primary cortical neurons (King, McBride et al. 2001, Franssen, Zhao et al. 2015) , however, the roles of their ligand binding on cell functions remain unknown due to the lack of connection of the integrin expression profile to specific functions of these neurons.

To this end, we have recently developed an integrin-binding array platform by immobilizing the short synthetic peptides that exclusively bind to 16 individual types of integrins that are commonly expressed on all vertebral cells on a 48-well cell culture plate (Jiang, Zeng et al. 2019). The array includes triplet sets of short peptide-coated wells in vertical arrangement for each type of integrin. Our prior testing of the ligand binding properties of the array confirmed the binding specificity of individual wells to its targeted type of integrin (Jiang, Zeng et al. 2019). Assessment of the cultured cells in the integrin-binding array in cell attachment, survival, proliferation/expansion, and differentiation allows us to identify the repertoire of integrin receptors on the cells that best support specific cell functions. Our preliminary studies of the array were performed on human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) and hiPSC-derived neuroepithelial progenitor cells (NEPs), and identified the key types of integrins and their binding peptides that mediate the adhesion and rapid expansion of each type of cells, as well as NEP generation from hiPSCs (Jiang, Zeng et al. 2019). Our work has for the first time correlated the cell type-specific integrin expression profile with their binding peptides to support specific cell functions. Such information may be readily translated to formulate peptide coating on biomaterials to support specific functions of cells of interest in a particular application.

In this study, we tested fetal rat primary cortical neurons on the integrin-binding array to identify the key integrins on the surfaces of these neurons to support the survival and growth of these neurons. Primary cortical neurons are the cells of interest in brain tissue regeneration following brain trauma or pathologies in rodent models. Our study identified three types of integrins, i.e., αvβ8, α5β1 and α3β1, particularly the former two, whose ligand-binding best supported the attachment and growth of pediatric rat primary cortical neurons in vitro. When immobilized to an injectable hydrogel in a 3-D culture, the αvβ8 and α5β1 integrin-binding peptides supported neurite outgrowth of fetal rat primary cortical neurons, suggesting their utility in functionalizing biomaterials for neural regeneration.

2. Materials and methods

Animals:

All the experiments involving animals were complied with the federal regulation and were approved by the Institutional Animals Care and Use Committee (IACUC), Virginia Commonwealth University. Fisher 344 timed pregnant rats were procured from the vendor (Charles River Laboratory, USA), and housed in our AAALAC approved animal facility, with a 12-hour light/dark cycle, water and food provided ad libitum.

2.1. Isolation of primary cortical neurons:

The rat primary cortical neurons were isolated from the embryonic day 18 following published protocols (Pacifici and Peruzzi 2012) . Briefly, the pregnant dam was deeply anaesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane in a Plexiglas chamber before sacrifice. The peritoneum of the dam was cut open to expose the embryonic sac. The embryonic sac was then carefully opened up and embryos were collected in the 50 ml tubes containing L-15 medium (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, USA). The head of the embryo was dissected out and the cerebral cortex was isolated in the sterile HBSS solution. The dissected cortical tissues were pooled and digested using the 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, USA) and 0.06% DNAse (Invitrogen, USA) for 30 minutes in 37°c. The cortical tissue was triturated, washed a few times and filtered with 70-micron filter to get single cell suspension. Then 10,000 cell / well was seeded in our custom-designed 48-well integrin-binding array platform that was prepared as previously described (Jiang, Zeng et al. 2019), and cultured with Neurobasal medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with growth factor B-27 (Gibco, USA), L-glutamine (Gibco, USA) and penicilin-streptomycin (Gibco, USA). For the control, a standard 48-well plate coated with Poly-D-lysine (Millipore, USA.) was used seeding with the same number of cells and same culture medium. As the aim of this study is to characterize the capacity of different integrin-binding peptides in supporting neuronal survival and general growth, the neuronal cultured was lasted for 7 days. During the 7-day culture, the media was changed every 48 hours. After 7 days in culture, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (4%PFA) for 30 minutes before used for immunostaining. The experiments were performed as a triplicate.

2.2. Immuno-fluorescence staining:

The 4%PFA fixed cells were first washed with PBS 2 times, 5 minutes each. The cells were then blocked with 10% horse serum for 1 hour followed by incubation with the primary antibodies including: immature neuronal marker Tuj-1 (1:1000, Biolegend, USA), mature neuronal marker MAP2 (1:500, EMD Millipore, USA) or astrocytes marker GFAP (1:1000, Dako) for overnight at 4°C with agitation. Following the primary antibody incubation, the cells were washed with PBS for 3 times, followed by incubation with the secondary antibodies prepared in 10% horse serum for 1 hour at room temperature. The secondary antibodies used were Alexa fluora 488 anti-rabbit IgG or Alex fluora 568 anti-mouse IgG (both 1:200, Invitrogen, USA). After incubation with the secondary antibodies, cells were then washed with PBS for 3 times at 10 minutes each. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (1:1000) for 10 minutes incubation, followed by two washes with PBS and cover slipped with Vectashield.

2.3. 3-dimensional culture:

After completing the integrin-binding array study, the peptides in the array platform that best supported the neuronal attachment and growth were immobilized in a polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based injectable hydrogel for neuronal growth in 3-D culture according to the previously described conjugation scheme (Li et al., 2014). The experiments were performed as a triplicate in a 48-well plate pre-coated with 20μl of hydrogel and incubated in 37°C for 30 minutes before seeding cells (10,000 cells/well). The custom-designed 0.8% hydrogel was diluted to 50% using the selected integrin-binding peptides with primary cortical neurons in Neurobasal medium. The integrin stock solution was made in 1XPBS as 4 mg/ml and the final concentration in the culture was adjusted to 0.5 mg/ml. The components of culture included: E18 rat primary neurons, selected integrin peptide, medium and hydrogel. All components were mixed up as a cocktail thoroughly before adding into the wells of the hydrogel pre-coated 48-well plate. A 50μl of prepared cocktail was added into each well, followed by incubation in 37° C for 30 minutes. Once the gel was fully set, 200μl of neurobasal media was gently poured from the top into the wells. The culture was grown for 7 days. The media was changed every 48 hours. After 7 days culture, the cells were fixed with 4% PFA for an hour and processed for immunostaining for TUJ1 and DAPI as described above. Images were captured using Olympus FV1000 Confocal Microscope.

2.4. Cell quantification:

For quantification of the percentage of Tuj-1 or MAP2 positive cells, 5 randomly selected fields per well were viewed and captured with a 20X objective using an inverted Olympus fluorescent microscope. The number of Tuj-1 or MAP2-positive cells was quantified against the total number of cells labeled with DAPI in the integrin cultures using Image-J software (NIH). Neurite outgrowth was traced according to the published protocol (Pool, Thiemann et al. 2008).

2.5. Statistical Analysis:

For the comparison of two groups, the unpaired t-test was used. For multiple group comparison, one-way ANOVA was used, followed by Tukey’s test or Bonferroni correction as post hoc analysis. GraphPad Prism, 7.0 software was used for data analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SEM in all figures. Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Growth properties of rat primary cortical neurons in integrin-binding array

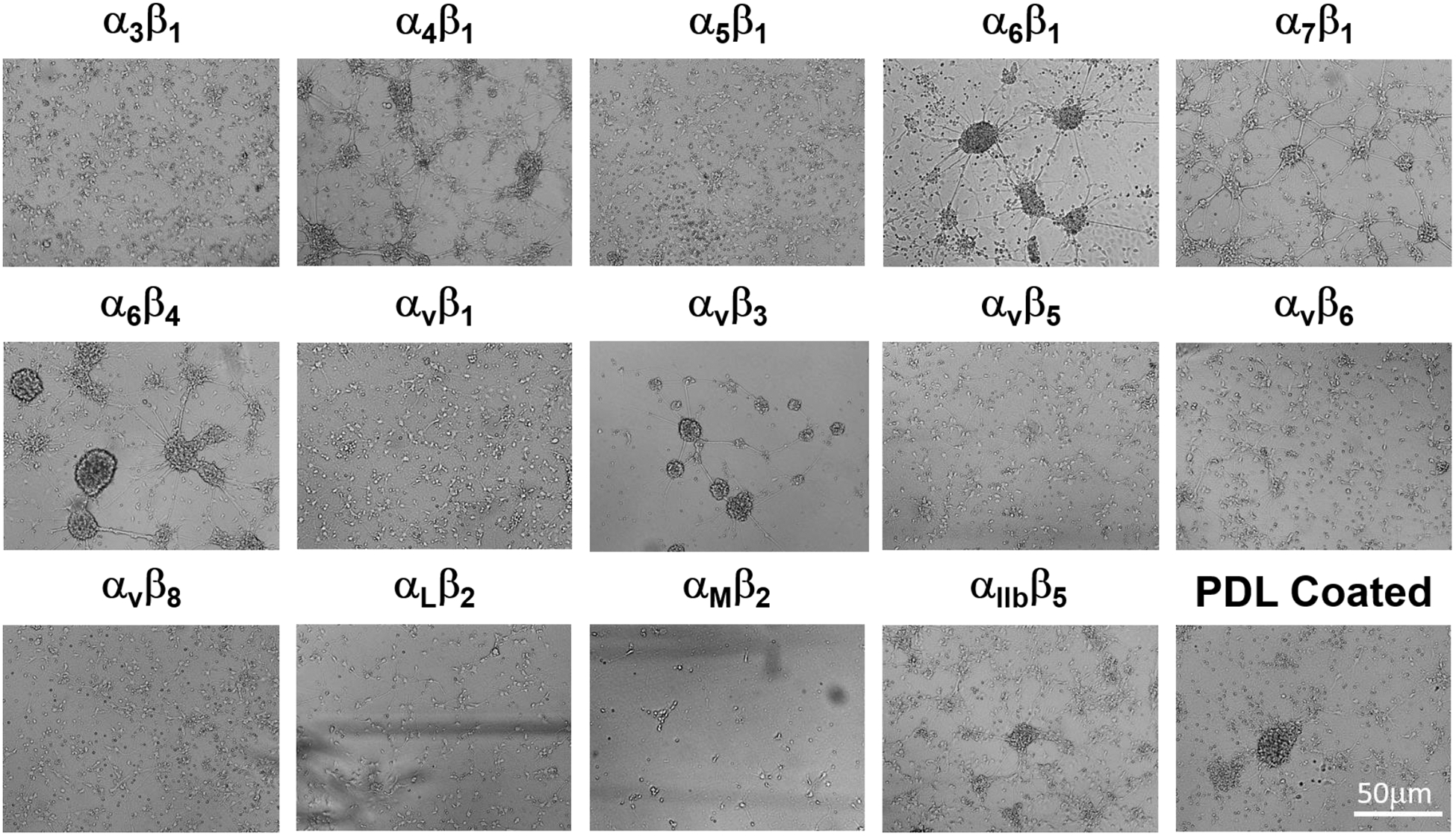

In this study, using an integrin-binding array platform, we tested the effect of short synthetic peptides binding to 16 types of integrins including α1β1, α2β1, α3β1, α4β1, α5β1, α6β1, α7β1, α6β4, αvβ1, αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, αvβ8, αLβ2, αMβ2 and αIIbβ3 on the survival and growth of rat primary cortical neurons. These integrins are commonly expressed on almost all vertebrate cells. The assessment of growth of E18 rat primary cortical neurons on the integrin-binding array platform revealed that the majority of the integrin-binding peptides supported the attachment and survival of the cortical neurons except for α1β1 and α1β2. Rat cortical neurons cultured in wells containing integrin-binding peptides for α5β1, α3β1, or αvβ8 showed robust growth characterized by neuronal attachment, neurite outgrowth, and branching without clumping (Fig. 1), whereas cells cultured in wells containing binding peptides for α1β1 or α1β2 exhibited sparse attachment, clumping, and subsequently died after a few days in culture (data not shown).

Fig. 1. Representative growth pattern of primary cortical neurons in the integrin array platform.

Representative phase contract images revealed the growth pattern of primary cortical neurons isolated from E18 rat pups in the integrin-coated plates after 7 days in culture. Optimal growth was observed in wells containing binding peptides for α5β1, α3β1 or αvβ8 integrins.

3.2. Neuronal growth and neurite branching of rat primary cortical neurons in integrin-binding array

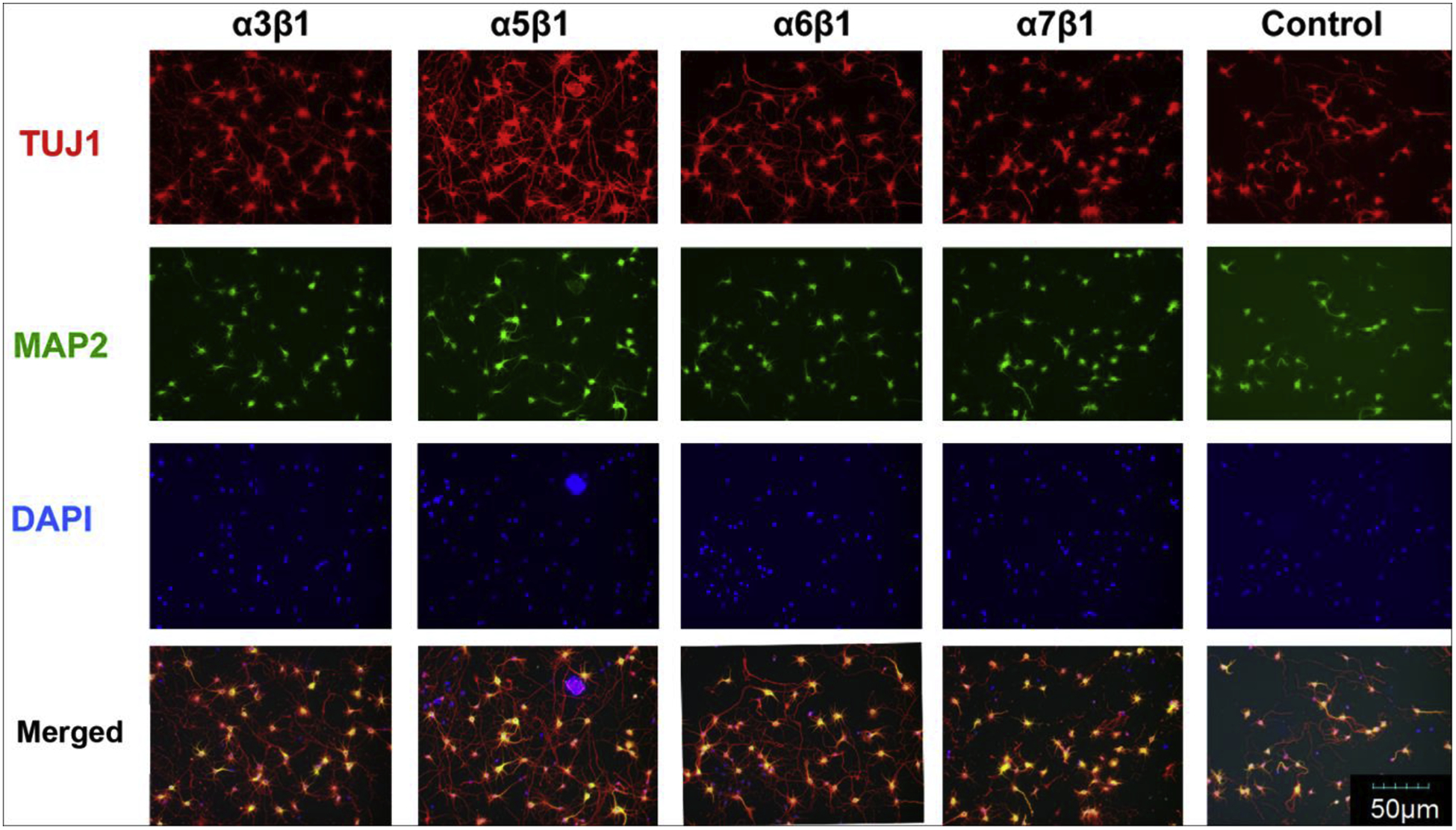

The primary neurons isolated from E18 were seeded on the integrin-binding peptide coated 48 plates at 3 different seeding densities of 50,000, 30,000 or 10,000 cells/well to examine the effect of integrin-binding peptides against different types of integrins on neuronal growth. The cultures were fixed at 7 days and processed for Tuj1, MAP2 and DAPI staining. The low cell seeding density of 10,000 cells/well was found to be optimal in assessing the number of Tuj1 or MAP2 positive cells and their neurite outgrowth. With the 7-day culturing, the majority of cells were Tuj1+, whereas the number of MAP2+ cells was relatively lower than the number of Tuj1+ cells, thus Tuj1+ cells were used for neurite outgrowth assessment. Five random selected fields of Tuj1 stained cells from each integrin peptide-coated well from each batch of the triplicated experiments were quantified using plug in Image J software (Pool, Thiemann et al. 2008). Among 16 types of integrins, the binding peptides for αvβ8, α5β1 and α3β1 integrins best supported the growth of cortical neurons, particularly the former two, as evidenced by the presences of dense Tuj-1+ cells with larger cell bodies and extended neurites in the wells containing the binding peptides for these three integrins (Fig. 2). Quantification analysis showed that the number of Tuj1+ cells per field was significantly higher in wells for αvβ8, and α5β1 integrins when compared with the cells grown in the standard culture condition in the control plates (Fig. 3A). The quantification of the Tuj1 expression levels in each culture condition by measuring Tuj1+ fluorescent intensity using Image-J revealed significantly higher expression of Tuj1 on binding peptides against αvβ8, and α5β1 integrins when compared to the control plates (Fig. 3B), consistent with the Tuj1+ cell number quantifications in Fig. 3A. We also assessed the extent of neurite outgrowth on different integrin-binding peptides with Tuj1+ cells, and found that a significantly better neurite outgrowth on binding peptides for αvβ8, α5β1 or α3β1 integrins when compared with the control culture condition (Fig. 3C). To assess the influence of binding peptide on neuronal maturation, we quantified the number of MAP2+ cells against the total number of cells labeled with DAPI in each well, and found a significantly higher ratio of MAP2-positive cells in wells for αvβ8 and α5β1 integrins when compared with the cells grown in the standard culture condition in the control plates (Fig. 3D), indicating that binding peptide for αvβ8 and α5β1 also promote neuronal maturation of the culture rat cortical neurons.

Fig. 2. Representative Integrin biding peptides in supporting the growth of primary cortical neurons.

The abundance of neurons expressing neuronal markers for immature neurons (Tuj-1, red) or mature neurons (MAP, green) in the integrin array platform was assessed using immunofluorecent staining. Representative images showed typical Tuj-1 and MAP staining patterns in selected integrin-binding peptide coated wells in comparison to poly-D-lysine coated control well. Note better neuronal growth in the well for α5β1.

Fig.3. Quantification analysis of the growth of the primary cortical neurons in the integrin array platform.

A. The number of Tuj1+ neurons per field was significantly higher when cells were grown on binding peptides for α5β1 or αvβ8. B. Higher Tuj1+ staining intensity was observed in neurons growing on peptides for α5β1 or αvβ8. C. Significantly better neurite outgrowth per field was observed when cells were grown on binding peptides for α3β1, α5β1, or αvβ8. D. Integrin-binding peptides for α5β1 or αvβ8 had significantly higher ratio of MAP2+ cells against total DAPI+ cells.

3.3. αvβ8 and α5β1 integrin-binding peptides promoted neurite outgrowth of rat primary cortical neurons in 3-D culture

Based on the results from the monolayer culture, we selected the αvβ8- and α5β1-binding peptides to be conjugated to a hydrogel for 3-D culture. A PEG-based injectable hydrogel was conjugated with the binding peptides for αvβ8 or α5β1 integrin, respectively, using the previously described scheme (Li et al., 2014). Rat primary cortical neurons were mixed with the αvβ8- or α5β1-binding peptide conjugated hydrogels before being seeded to hydrogel pre-coated wells for 3-D culture (n=8 per condition). Cells in 3-D culture were fixed after 7-days in culture and processed for immunostaining for Tuj1 and DAPI. Images were taken with confocal microscope. Neurite outgrowth was traced according to the published protocol (Pool, Thiemann et al. 2008). When compared to the no-peptide blank hydrogel control, the presence of the αvβ8- or α5β1-binding peptides in peptide-conjugated hydrogels greatly promoted neurite extension, outgrowth, branching, and network formation (Fig 4A). Such effect was particularly pronounced in the αvβ8-binding peptide-conjugated hydrogel group, as evidenced by extensive neurite outgrowth and branching, and robust neuronal network formation (Fig 4A). Quantification of the neurite outgrowth length revealed significantly greater outgrowth lengths in neurons cultured within the αvβ8- or α5β1-binding peptide-conjugated hydrogels when compared to the no-peptide blank hydrogel (Fig. 4B). Again, such effect was most pronounced with the αvβ8-binding peptide-conjugated hydrogel group (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Growth of rat primary cortical neurons in 3-dimensional culture condition.

A Immunofluorescent staining of Tuj1 and DAPI showed neurite outgrowth pattern of primary neurons in 3-D culture within selected integrin binding peptide-conjugated hydrogels and the no-peptide blank hydrogel control. Neurons cultured in αvβ8- or α5β1-binding peptide-conjugated hydrogels had longer neurites with more branching. B. Quantification analysis of neurite outgrowth length revealed significantly greater neurite outgrowth lengths of neurons cultured in αvβ8- or α5β1-binding peptide-conjugated hydrogels when compared to the no-peptide blank hydrogel control.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we cultured rat primary cortical neurons on the integrin-binding peptide array platform and identified binding peptides for three types of integrins, i.e., αvβ8, α5β1 and α3β1, particularly the former two, which can effectively support the survival and neurite outgrowth of the neurons in culture. The binding peptides to the identified integrins using the integrin-binding array platform were subsequently conjugated to an injectable hydrogel which supported survival and neurite outgrowth of rat primary cortical neurons in 3D culture, confirming the utility of the identified integrin type-specific binding peptides on the integrin-binding array platform in functionalizing biomaterials to support specific functions of cells of interest.

Rat primary cortical neuron cultures are an indispensable model system for study neuronal development and regeneration, neurotoxicity screening, drug discovery, and physiopathology of neurological trauma and diseases. When compared to cell lines, primary neurons preserve the characteristics of their neural tissue of origin, therefore, representing more physiologically relevant cells. Although rat primary cortical neurons have been broadly used in tissue cultures, the trophic properties of the substrates that are required to support their survival and growth are far from being defined. In particular, the conventional poly-D-lysine treatment of culture substrates has marginally supported the attachment and growth of these cells. When cultured on the untreated surfaces of regular polystyrene plastic wares and in the absence of exogenous trophic factors, these primary cortical neurons barely attached and quickly died from apoptosis, yet the death was prevented by supplemented neurotrophic factors (Catapano, Arnold et al. 2001), suggesting the importance of the substrate trophic properties in supporting the attachment and growth of the neurons. Since integrins are the major cell surface receptors that mediate cell-environment and cell-cell interactions, these early studies have prompted us to examine the effect of integrin-ligand binding on the survival and growth of rat primary cortical neurons in culture.

The advent of the integrin-binding array in our lab offers a novel tool for the study of integrin-mediated cell functions. Instead of using a top-down approach which seeks to characterize the integrin expression profile on the surfaces of cells of interest, the integrin-binding array uses a bottom-up approach, which allows direct readout of the set of integrins on cell surfaces that mediate specific cell functions without getting into the cumbersome mapping of molecular identities that may not be relevant to cell functions of interest. The high binding affinity and specificity of the immobilized peptides to specific type of integrins on the integrin-binding array also obviate the challenges of dissecting the integrin-ligand binding specificity in conventional antibody inhibition assay in which the antibody inhibits overall cell adhesion onto a matrix protein (e.g., laminin) without pinpointing the types of integrins of action. Pieces of information yielded from isolated studies on integrin-binding specificities and their effects on cell functions may now be integrated into a database to define substrate trophic specifications to support specific functions of cells of interest for a wide variety of biomedical purposes. In general, any anchorage-dependent vertebrate cells may be tested on the integrin-binding array platform to delineate the set of integrins that mediate specific cell functions in a cell type-specific manner. The corresponding binding peptides to each type of the identified integrins may be readily functionalized to biomaterial substrates to support the specific functions of the cells of interests. We have previously reported that binding peptides of integrin α5β1, αVβ1, and αIIbβ3 supported cell adhesion of hiPSCs and iPSC-derived NEPs, whereas α5β1 binding peptide also supported rapid expansion of iPSCs and NEPs (Jiang, Zeng et al. 2019). Our ongoing study has also found the supportive effect of several integrin binding peptides for cultured rat primary cortical endothelial cells (data not shown). The present study has demonstrated the effect of the binding peptides of the three identified integrins, i.e., αvβ8, α5β1 and α3β1 on the integrin-binding array in supporting the neurite outgrowth and neuronal network formation of rat primary cortical neurons in hydrogels in 3D culture. These integrin-binding peptide-functionalized hydrogels will be utilized in future in vivo studies as biomaterials or as coatings on biomaterials to support neuronal repopulation of brain lesion for functional tissue regeneration following brain insults in experimental rat models. The density and the ratio of different integrin-binding peptides to be immobilized onto the biomaterials may be further optimized to maximize the potential synergistic effects of binding to each of the identified integrins by way of the integrin-binding array on specific cell functions under the tissue conditions of interest.

The cerebral cortex is the location of major tissue damage as a result of TBI. Following TBI, the repair of the injured brain may be possible by neural stem cell (NSC) transplantation or manipulating endogenous precursors in situ. These strategies will likely require an engineered biomaterial substrate at the lesion site to support the survival of transplanted cells and their differentiation into specific neuronal lineages. To ensure efficient repopulation and reconstruction of lost circuitry at the TBI lesion site, the biomaterial substrate needs to support the attachment, survival and growth of neurons differentiated from the transplanted NSCs. Our present study identified binding peptides for 3 types of integrins, i.e., αvβ8, α5β1 and α3β1 in effectively supporting the survival and neurite outgrowth of rat primary cortical neurons in culture. The three integrins that were recognized as essential in mediating the attachment, survival, and neurite outgrowth of rat primary cortical neurons are consistent with the existing literatures (Anton, Kreidberg et al. 1999, Bi, Lynch et al. 2001, Schmid, Shelton et al. 2004). The previous studies documented the effects of individual types of these three integrins on rat cortical neuron biology, yet there has not been a single study that has collectively identified all 3 types of integrins in mediating special cell functions such as survival and growth of rat primary cortical neurons. Among these three integrins, αvβ8 is predominantly expressed in the brain, suggesting a brain-specific function (Moyle, Napier et al. 1991). The αvβ8 integrin distributes in the synapses in the brain including the cortical layers (Nishimura, Boylen et al. 1998, Milner, Huang et al. 1999) and its only known ligand is vitronectin, which is widely produced by diverse cell types in the brain such as neurons and astrocytes during normal and pathological conditions (Gladson, Seegmiller et al. 1990, Neugebauer, Emmett et al. 1991). It is believed that binding of αvβ8 to its ligand regulates synaptic adhesion and plasticity, and is responsible for the highly specific synaptic contacts in the brain (Muller, Wang et al. 1996). The α5β1 integrin is expressed in the neural progenitors of the ventricular zone during cerebral cortex development, and regulates neural morphology and migration, as well as cortical lamination during cortical development (Marchetti et al., 2010). It binds to the isoforms of fibronectin and osteopontin (Humphries, Byron et al. 2006), and is necessary for neurite outgrowth of some specific neurons such as dopaminergic neurons (Izumi, Wakita et al. 2017). The α5β1 integrin is also involved in regeneration of peripheral nerve following injury as increased expression was observed in axon growth cones (Yanagida, Tanaka et al. 1999). The α3β1 integrin has been known as a major receptor to laminin (Nishiuchi, Murayama et al. 2003), the major type of ECM proteins in the brain. Binding of integrin to laminin play important roles in cell attachment, differentiation, migration, signaling, and matrix production (Schmid, Shelton et al. 2004). In particular, binding of α3β1 integrin on fetal cortical neuron surfaces to laminin was shown to regulate the migration of these neurons (Rout, 2013).

In all, we have proved the concept of an integrin-binding array platform to identify the key integrins on the surface of cells of interest to support specific cell functions. The identified integrin-binding peptides are readily immobilized to biomaterial substrates in biomaterial-assisted tissue repair or regeneration by supporting the key functions of the cells of interest. Ongoing work in the lab is focused on formulating the identified integrin-binding peptides to an injectable hydrogel to promote neural regeneration following a focal brain injury. Meanwhile, the novel integrin-binding array platform is being testing for a variety of cell types that are important in the regeneration of other types of tissues.

Highlights:

Optimization of culturing condition for primary cortical neurons with synthetic integrin-binding peptides

Effect of synthetic integrin-binding peptides on the growth and survival of primary cortical neurons studied in vitro.

Significant improvement of neuronal growth and survival at the present of binding peptides for αvβ8 or α5β1 integrins.

3-dimensional culture with hydrogel and binding peptides for αvβ8 or α5β1 integrins has conducive effect for the growth of primary cortical neurons.

Acknowledgements

The authors were supported by NIH grant RO1 NS093985 (Sun, Zhang, Wen) and RO1 NS101955 (Sun).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest associated with the studies presented in this manuscript.

References:

- Anton E, Kreidberg JA and Rakic P (1999). “Distinct functions of α3 and αv integrin receptors in neuronal migration and laminar organization of the cerebral cortex.” Neuron 22(2): 277–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi X, Lynch G, Zhou J and Gall CM (2001). “Polarized distribution of α5 integrin in dendrites of hippocampal and cortical neurons.” Journal of Comparative Neurology 435(2): 184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokel C and Brown NH (2002). “Integrins in development: moving on, responding to, and sticking to the extracellular matrix.” Dev Cell 3(3): 311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catapano LA, Arnold MW, Perez FA and Macklis JD (2001). “Specific neurotrophic factors support the survival of cortical projection neurons at distinct stages of development.” J Neurosci 21(22): 8863–8872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Arcangelis A and Georges-Labouesse E (2000). “Integrin and ECM functions: roles in vertebrate development.” Trends in Genetics 16(9): 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franssen EH, Zhao R-R, Koseki H, Kanamarlapudi V, Hoogenraad CC, Eva R and Fawcett JW (2015). “Exclusion of integrins from CNS axons is regulated by Arf6 activation and the AIS.” Journal of Neuroscience 35(21): 8359–8375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladson C, Seegmiller J, Smith J, Klier G and Cheresh D (1990). “Glioblastoma cells synthesize and secrete the adhesive protein vitronectin.” Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology 49(3). [Google Scholar]

- Humphries JD, Byron A and Humphries MJ (2006). “Integrin ligands at a glance.” Journal of cell science 119(19): 3901–3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO (2002). “Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines.” cell 110(6): 673–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi Y, Wakita S, Kanbara C, Nakai T, Akaike A and Kume T (2017). “Integrin alpha5beta1 expression on dopaminergic neurons is involved in dopaminergic neurite outgrowth on striatal neurons.” Sci Rep 7: 42111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Zeng X, Xue B, Campbell D, Wang Y, Sun H, Xu Y and Wen X (2019). “Screening of pure synthetic coating substrates for induced pluripotent stem cells and iPSC-derived neuroepithelial progenitors with short peptide based integrin array.” Exp Cell Res 380(1): 90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King VR, McBride A and Priestley JV (2001). “Immunohistochemical expression of the α5 integrin subunit in the normal adult rat central nervous system.” Journal of neurocytology 30(3): 243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Liu X, Josey B, Chou CJ, Tan Y, Zhang N and Wen X (2014). “Short laminin peptide for improved neural stem cell growth.” Stem Cells Transl Med 3(5): 662–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti G, Escuin S, van der Flier A, De Arcangelis A, Hynes RO, Georges-Labouesse E (2010). “Integrin alpha5beta1 is necessary for regulation of radial migration of cortical neurons during mouse brain development.” Eur J Neurosci 31(3): 399–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner R and Campbell IL (2002). “The integrin family of cell adhesion molecules has multiple functions within the CNS.” Journal of neuroscience research 69(3): 286–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner R, Huang X, Wu J, Nishimura S, Pytela R and Sheppard D (1999). “Distinct roles for astrocyte alphavbeta5 and alphavbeta8 integrins in adhesion and migration.” J Cell Sci 112(23): 4271–4279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mould AP, Akiyama SK and Humphries MJ (1995). “Regulation of Integrin α5β1-Fibronectin Interactions by Divalent Cations Evidence for Distinct Classes of Binding Sites for Mn2+, Mg2+, and Ca2+.” Journal of Biological Chemistry 270(44): 26270–26277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyle M, Napier MA and McLean JW (1991). “Cloning and expression of a divergent integrin subunit beta 8.” J Biol Chem 266(29): 19650–19658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Wang C, Skibo G, Toni N, Cremer H, Calaora V, Rougon G and Kiss JZ (1996). “PSA-NCAM is required for activity-induced synaptic plasticity.” Neuron 17(3): 413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer K, Emmett C, Venstrom K and Reichardt L (1991). “Vitronectin and thrombospondin promote retinal neurite outgrowth: developmental regulation and role of integrins.” Neuron 6(3): 345–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuis B, Haenzi B, Andrews MR, Verhaagen J and Fawcett JW (2018). “Integrins promote axonal regeneration after injury of the nervous system.” Biological Reviews 93(3): 1339–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura SL, Boylen KP, Einheber S, Milner TA, Ramos DM and Pytela R (1998). “Synaptic and glial localization of the integrin alphavbeta8 in mouse and rat brain.” Brain Res 791(1–2): 271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiuchi R, Murayama O, Fujiwara H, Gu J, Kawakami T, Aimoto S, Wada Y and Sekiguchi K (2003). “Characterization of the ligand-binding specificities of integrin alpha3beta1 and alpha6beta1 using a panel of purified laminin isoforms containing distinct alpha chains.” J Biochem 134(4): 497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxvig C and Springer TA (1998). “Experimental support for a β-propeller domain in integrin α-subunits and a calcium binding site on its lower surface.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95(9): 4870–4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacifici M and Peruzzi F (2012). “Isolation and culture of rat embryonic neural cells: a quick protocol.” JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments)(63): e3965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plow EF, Haas TA, Zhang L, Loftus J and Smith JW (2000). “Ligand binding to integrins.” Journal of Biological Chemistry 275(29): 21785–21788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pool M, Thiemann J, Bar-Or A and Fournier AE (2008). “NeuriteTracer: a novel ImageJ plugin for automated quantification of neurite outgrowth.” Journal of neuroscience methods 168(1): 134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rout UK (2013). “Roles of Integrins and Intracellular Molecules in the Migration and Neuritogenesis of Fetal Cortical Neurons: MEK Regulates Only the Neuritogenesis.” Neurosci J 2013: 859257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid RS, Shelton S, Stanco A, Yokota Y, Kreidberg JA and Anton E (2004). “α3β1 integrin modulates neuronal migration and placement during early stages of cerebral cortical development.” Development 131(24): 6023–6031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seebeck F, Marz M, Meyer AW, Reuter H, Vogg MC, Stehling M, Mildner K, Zeuschner D, Rabert F and Bartscherer K (2017). “Integrins are required for tissue organization and restriction of neurogenesis in regenerating planarians.” Development 144(5): 795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada Y, Ye X and Simon S (2007). “The integrins.” Genome biology 8(5): 215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Flier A and Sonnenberg A (2001). “Function and interactions of integrins.” Cell and tissue research 305(3): 285–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagida H, Tanaka J and Maruo S (1999). “Immunocytochemical localization of a cell adhesion molecule, integrin alpha5beta1, in nerve growth cones.” J Orthop Sci 4(5): 353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]