To the Editor:

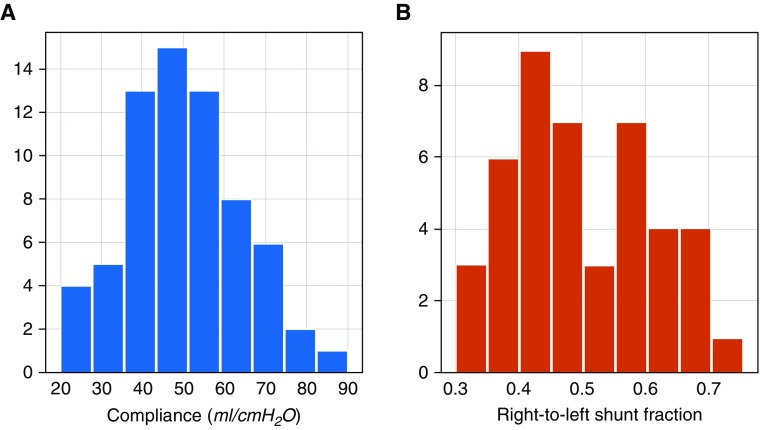

In northern Italy, an overwhelming number of patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia and acute respiratory failure have been admitted to our ICUs. Attention is primarily focused on increasing the number of beds, ventilators, and intensivists brought to bear on the problem, while the clinical approach to these patients is the one typically applied to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), namely, high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) and prone positioning. However, the patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, despite meeting the Berlin definition of ARDS, present an atypical form of the syndrome. Indeed, the primary characteristic we are observing (and has been confirmed by colleagues in other hospitals) is a dissociation between their relatively well-preserved lung mechanics and the severity of hypoxemia. As shown in our first 16 patients (Figure 1), a respiratory system compliance of 50.2 ± 14.3 ml/cm H2O is associated with a shunt fraction of 0.50 ± 0.11. Such a wide discrepancy is virtually never seen in most forms of ARDS. Relatively high compliance indicates a well-preserved lung gas volume in this patient cohort, in sharp contrast to expectations for severe ARDS.

Figure 1.

(A) Distributions of the observations of the compliance values observed in our cohort of patients. (B) Distributions of the observations of the right-to-left shunt values observed in our cohort of patients.

A possible explanation for such severe hypoxemia occurring in compliant lungs is a loss of lung perfusion regulation and hypoxic vasoconstriction. Actually, in ARDS, the ratio of the shunt fraction to the fraction of gasless tissue is highly variable, with a mean of 1.25 ± 0.80 (1). In eight of our patients with a computed tomography scan, however, we measured a ratio of 3.0 ± 2.1, suggesting a remarkable hyperperfusion of gasless tissue. If this is the case, the increases in oxygenation with high PEEP and/or prone positioning are not primarily due to recruitment, the usual mechanism in ARDS (2), but instead, in these patients with poorly recruitable lungs (3), result from the redistribution of perfusion in response to pressure and/or gravitational forces. We should consider that 1) in patients who are treated with continuous positive airway pressure or noninvasive ventilation and who present with clinical signs of excessive inspiratory efforts, intubation should be prioritized to avoid excessive intrathoracic negative pressures and self-inflicted lung injury (4); 2) high PEEP in a poorly recruitable lung tends to result in severe hemodynamic impairment and fluid retention; and 3) prone positioning of patients with relatively high compliance provides a modest benefit at the cost of a high demand for stressed human resources.

Given the above considerations, the best we can do while ventilating these patients is to “buy time” while causing minimal additional damage, by maintaining the lowest possible PEEP and gentle ventilation. We need to be patient.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0817LE on March 30, 2020

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Cressoni M, Caironi P, Polli F, Carlesso E, Chiumello D, Cadringher P, et al. Anatomical and functional intrapulmonary shunt in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:669–675. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000300276.12074.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gattinoni L, Caironi P, Cressoni M, Chiumello D, Ranieri VM, Quintel M, et al. Lung recruitment in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1775–1786. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pan C, Chen L, Lu C, Zhang W, Xia J-A, Sklar MC, et al. Lung recruitability in SARS-CoV-2–associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: a single-center observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0527LE. [online ahead of print] 23 Mar 2020; DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0527LE. Published in final form as Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;201:1294–1297 (this issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brochard L, Slutsky A, Pesenti A. Mechanical ventilation to minimize progression of lung injury in acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:438–442. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1081CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.