Summary

In patients with severe clinical features of COVID-19 infection, the proportion of patients with acute pulmonary embolus was 23% (95% CI: 15%, 33%) on pulmonary CT angiography.

Introduction

Chest CT plays an important role in optimizing the management of patients with COVID-19 while also eliminating alternate diagnoses or added pathologies, particularly for acute pulmonary embolism (1). A few studies and isolated clinical cases of COVID-19 pneumonia with coagulopathy and pulmonary embolus have recently been published (2–4). The main objective of our study was to evaluate pulmonary embolus in association with COVID-19 infection using pulmonary CT angiography.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study was approved by our institutional review board. It followed the ethical guidelines of the declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was waived. Three authors (F.G., J.B., P.C.) had access to the study data. No author has any conflict of interest to declare in relation to this study.

Patients

The inclusion criteria were consecutive adult patients (≥ 18 years old) with a RT-PCR diagnosis (NucleoSpin RNA Virus kit, Macherey-Nagel Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA) of SARS-CoV-2 or a strong clinical suspicion of COVID-19 (fever and/or acute respiratory symptoms, exposure to an individual with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection) who underwent a chest CT scan between March 15 to April 14, 2020 at a single center. In patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, chest CT scan was performed when clinical features of severe disease were present (e.g., requirement for mechanical ventilation [IMV]) or underlying comorbidities). Patients with non-contrast chest CT scans were excluded.

CT Protocol

Our routine protocol for patients with severe clinical features of COVID-19 infection was multidetector pulmonary CT angiography using 256 slice multi-detector CT (Revolution, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) after intravenous injection of 60 ml iodinated contrast agent (Iomeprol 400 Mg I/mL, Bracco Imaging, Milan, IT) at a flow rate of 4 mL/s, triggered on the main pulmonary artery. CT scan settings were 120 kVp, 80 x .625 mm, rotation time .28 s, average tube current 300 mA, pitch .992 and CTDIvol 4.28 mGy.

Imaging Analysis. Chest CT scan pattern of COVID-19 and presence of pulmonary embolus were independently analyzed by two chest radiologists (J.B. and F.G. with 11 and 6 years of experience) on a PACS workstation (Carestream Health, Rochester, NY). Readers were blinded to patient status as well as clinical and biological features. In cases of discordance, a simultaneous reading to reach consensus was achieved.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between continuous variables were performed using Student t-test when distribution was normal. Comparison between categorical variables were performed using Pearson's chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. To determine the clinical factors associated with pulmonary embolus, we considered the CT extent of lesions, need for invasive mechanical ventilation, demographics, and the presence of comorbidities as potential independent variables in a logistic regression model. A P value of less than .05 indicated a significant difference. All analyses were performed with R version 3.4.4 (R Core Team 2017).

Results

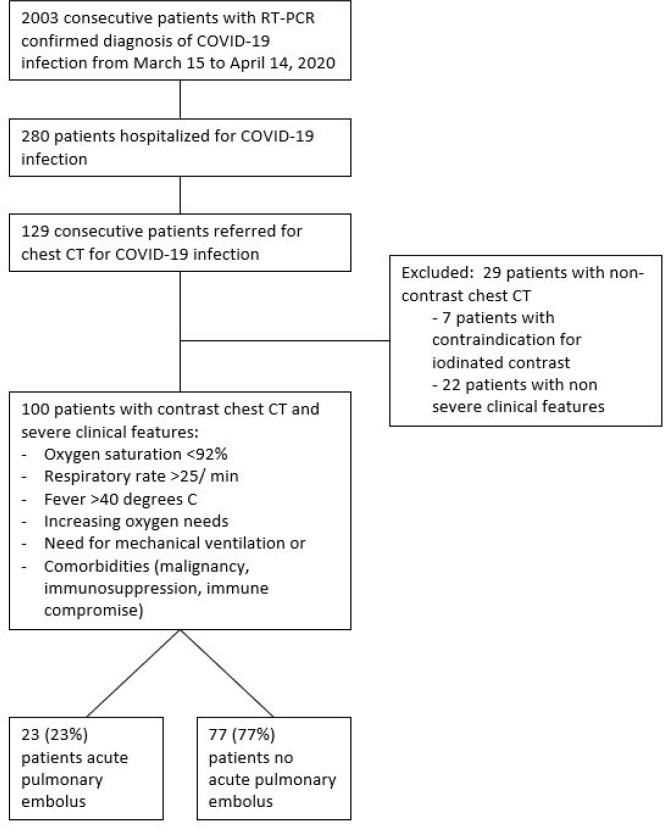

Of 2003 patients diagnosed with COVID-19, 280 patients were hospitalized during the study period. Of these, 129 of 280 (46%) hospitalized patients underwent CT scan at an average of 9 ± 5 days after symptom onset. Twenty-nine patients had non-contrast chest CT due to contraindication to iodinated contrast or non-severe clinical features and thus were excluded. Finally, 100 patients with COVID-19 infection and severe clinical features were included were examined with contrast enhanced CT (Figure 1). The mean age of the included patients was 66 ± 13 years old, with 70 men and 30 women (Table; Appendix E1 [online]). Of 100 patients meeting inclusion criteria, 23 (23%, [95%CI, 15-33%]) patients had acute pulmonary embolism (Figure 2; Appendix E1 [online]). Patients with pulmonary embolus were more frequently in the critical care unit than those without pulmonary embolus (17 (74%) vs 22 (29%) patients, p<.001), required mechanical ventilation more often (15 (65%) versus 19 (25%) patients, p<.001) and had longer delay from symptom onset to CT diagnosis of pulmonary embolus (12 ± 6 versus 8 ± 5 days, p<.001), respectively (Table). In multivariable analysis, requirement for mechanical ventilation (OR = 3.8 IC95% [1.02 - 15], p=.049) remained associated with acute pulmonary embolus.

Figure 1:

Flow chart of the study.

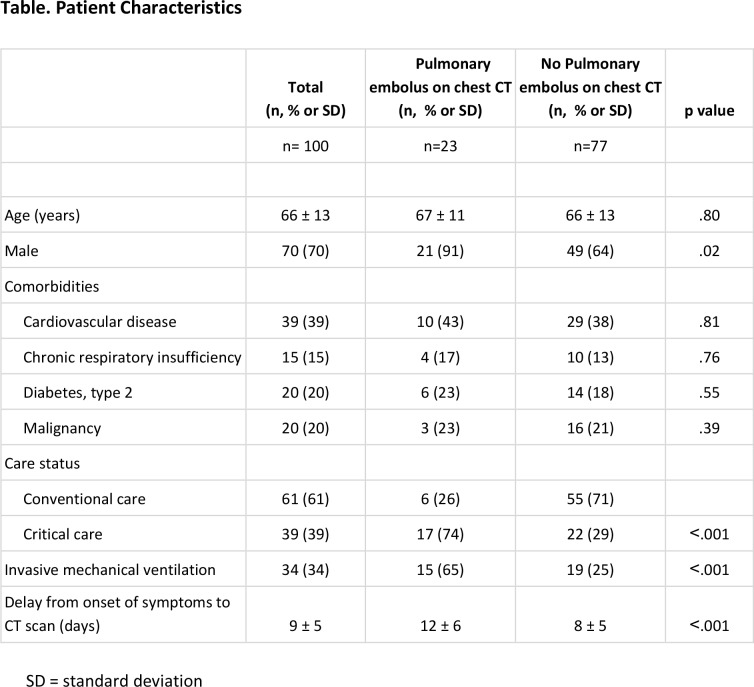

Table.

Patient Characteristics

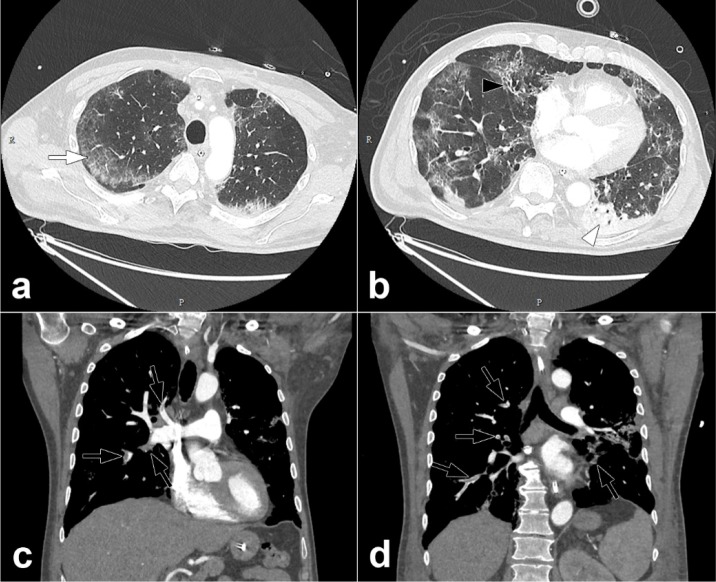

Figure 2:

Pulmonary CT angiography of a 68 year old male. The CT scan was obtained 10 days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms and on the day the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit. Axial CT images (lung windows) (a,b) show peripheral ground-glass opacities (arrow) associated with areas of consolidation in dependent portions of the lung (arrowheads). Interlobular reticulations, bronchiectasis (black arrow) and lung architectural distortion are present. Involvement of the lung volume was estimated to be between 25% and 50%. Coronal CT reformations (mediastinum windows) (c,d) show bilateral lobar and segmental pulmonary embolism (black arrows).

Discussion

Our study points to a high prevalence of acute pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 (23%, [95%CI, 15-33%]). Pulmonary embolus was diagnosed at mean of 12 days from symptom onset. Patients with pulmonary embolus were more likely require care in the critical care unit and to require mechanical ventilation than those without pulmonary embolus (Table).

Current guidelines (1,5,6) recommend performing non-contrast chest CT to assess the COVID-19 CT pattern and its extension. However, prior reports suggested coagulopathy associated with COVID-19 infection [e.g. (2,3)]. Further, these patients have frequent risk factors for pulmonary embolus (e.g. mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit admission). Therefore, we routinely performed contrast enhanced CT for COVID-19 patients with severe clinical features to evaluate the lung parenchyma as well as to evaluate other complications that may result in respiratory distress.

Our results showed frequent (23%) pulmonary embolus in patients with COVID-19. In multivariate analysis, pulmonary embolus was associated with invasive mechanical ventilation and male gender. Interestingly, extent of lesions was not a associated with pulmonary embolus. We acknowledge the preliminary nature of these findings, including its retrospective nature and limited sample size. Important clinical markers were not available that may explain or be associated with pulmonary embolus, including D-dimer (only 22 of 100 patients had D-dimer levels available). Nevertheless, our results suggest that patients with severe clinical features of COVID-19 may have associated acute pulmonary embolus. Therefore, the use of contrast enhanced CT rather than routine non-contrast CT may be considered for these patients.

APPENDIX

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- Pulmonary embolus

- Acute Pulmonary Embolism

- COVID-19

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- CTA

- Computed Tomography Angiography

- IMV

- Invasive Mechanical Ventilation

- RT-PCR

- real-time Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction

- SARS-CoV-2

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

References

- 1.Revel M-P, Parkar AP, Prosch H, Silva M, Sverzellati N, Gleeson F, et al. COVID-19 patients and the Radiology department – advice from the European Society of Radiology (ESR) and the European Society of Thoracic Imaging (ESTI). 2020;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danzi GB, Loffi M, Galeazzi G, Gherbesi E. Acute pulmonary embolism and COVID-19 pneumonia: a random association? Eur Heart J. 2020 Mar 30;ehaa254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie Y, Wang X, Yang P, Zhang S. COVID-19 Complicated by Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2020 Apr 1;2(2):e200067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goeijenbier M, van Wissen M, van de Weg C, Jong E, Gerdes VEA, Meijers JCM, et al. Review: Viral infections and mechanisms of thrombosis and bleeding. J Med Virol. 2012 Oct;84(10):1680–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpson S, Kay FU, Abbara S, Bhalla S, Chung JH, Chung M, et al. Radiological Society of North America Expert Consensus Statement on Reporting Chest CT Findings Related to COVID-19. Endorsed by the Society of Thoracic Radiology, the American College of Radiology, and RSNA. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2020 Apr 1;2(2):e200152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin GD, Desai SR, Goo JM, Inoue Y, Tomiyama N, Ryerson CJ, et al. The Role of Chest Imaging in Patient Management during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multinational Consensus Statement from the Fleischner Society.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.