Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic will have a profound impact on Radiology practices across the country. Policy measures adopted to slow the transmission of disease are decreasing the demand for imaging independent of COVID-19. Hospital preparations to expand crisis capacity are further diminishing the amount of appropriate medical imaging that can be safely performed. While economic recessions generally tend to result in decreased health care expenditures, radiology groups have never experienced an economic shock that is simultaneously exacerbated by the need to restrict the availability of imaging. Outpatient heavy practices will feel the biggest impact of these changes, but all imaging volumes will decrease. Anecdotal experience suggests that radiology practices should anticipate 50%-70% decreases in imaging volume that will last a minimum of 3-4 months, depending on the location of practice and the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic in each region. The CARES Act provides multiple means of direct and indirect aid to healthcare providers and small businesses. The final allocation of this funding is not yet clear, and it is likely that additional congressional action will be necessary to stabilize health care markets. Administrators and practice leaders need to be proactive with practice modifications and financial maneuvers that can position them to emerge from this pandemic in the most viable economic position. It is possible that this crisis will have lasting effects on the structure of the radiology field.

MAIN BODY

The COVID-19 pandemic is having a profound impact on the United States. It is the most serious public health crisis in most of our lives and the most significant geopolitical event of our generation. The necessary policy response to quell its spread and the resultant downstream effects have had significant detrimental effects on the economy; economic activity in many sectors has evaporated. Stock market indices have fallen significantly from their pre-pandemic highs1 and unemployment has risen substantially above its recent nadir of 3.5%2. Nearly 17 million Americans filed for unemployment benefits in the 3-week period ending April 43. As the front line of this response, academic, private and community care systems are all experiencing significant lost revenues in addition to increased expenditures from facility modifications and increased staffing. With nationwide community spread, no region will escape the stresses of this event, though some will have more time to prepare.

The ideal policy response to minimize the loss of life and economic hardship is not yet clear given the limited and incomplete data that we have to date4. What can be said with relative certainty is that the next 6-12 months will require close coordination between the public sector, health care delivery systems, and individual behavior. The goal is to spread out the demand for COVID-19 related health care, which will provide health systems sufficient time to increase capacity; if successful, we will prevent or limit the amount of hospitals that are overwhelmed and stretched beyond capacity. Whether this capacity is reached will be determined by how demand and supply change in the coming months.

The demand for health services is driven by the government policy response and individual behavior. In the absence of federal mandates, state governments have enacted varying levels of mandatory closures and shelter-in-place orders. These policy responses affect the demand for health services independent of COVID-19 related sequelae. Shelter-in-place orders have dramatically cut the number of traffic collisions and led to decreased crime across the country. Suspension of collegiate, scholastic, and community athletics has resulted in less trauma. Social distancing recommendations help minimize the transmission of other communicable diseases such as influenza. While the net effect of these policies is decreased demand, there are exceptions; increased gun sales, increased domestic violence, and exacerbation of mental illness are all potential sources of higher demand for certain health services. Perhaps even more troubling, reduced rates of admission for heart attacks, strokes and other common emergencies suggest that patients may be avoiding necessary care out of a fear of going to the hospital5.

The supply of health care is altered directly by our care delivery systems. Hospitals are actively expanding their capacity for basic and critical care beds. Important resources such as personal protective equipment (PPE) and drugs must be preserved and sourced, often at extraordinary expense. Additionally, hospitals must be cognizant of their potential to inadvertently worsen local outbreaks through nosocomial transmission6. These precautionary maneuvers necessitate curtailing of nonurgent and elective care, including medical imaging. Some radiologists, including trainees, are being redeployed to other roles throughout the healthcare continuum. These measures free up physical resources for bed expansion, prevent the use of PPE that will be needed to care for COVID-19 patients, and limit additional transmission potential.

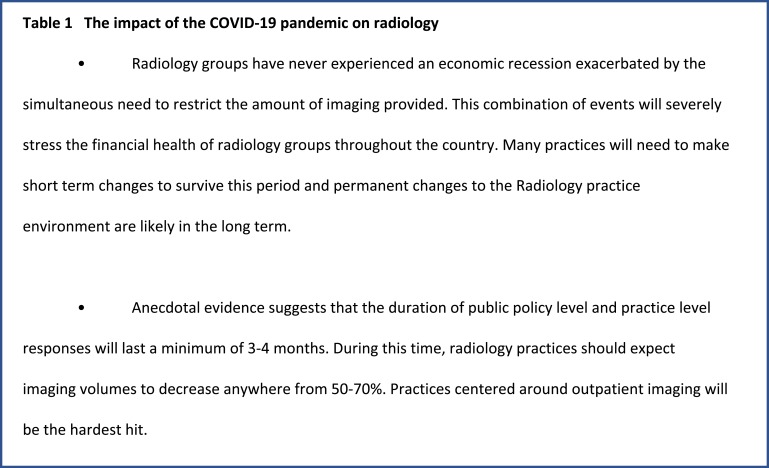

The net decrease in demand for non-COVID-19 related health care and concomitant capacity expansion are encouraging developments for the collective public health response. However, their combination is also financially devastating for many medical specialties, including Radiology (Table 1). While economic recessions tend to result in decreased health expenditures7, the healthcare industry has never experienced an economic shock that is simultaneously exacerbated by the need to restrict its supply of certain services. Recession-induced changes in insurance coverage and reimbursement were most recently exemplified by the 2008 financial crisis and its aftermath. Compared to prior recessions, the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicaid expansion (in the 37 states that have adopted expansion) have created a more inclusive safety net, decreasing the overall percentage of Americans that will be uninsured. However, reimbursement of safety net programs is generally lower when compared to commercial insurance and the net effect will be a significant drop in revenue for providers. There is much uncertainty about whether the economic recovery from this crisis will be U-shaped or V-shaped and the final extent of these macro level recession effects on reimbursement will ultimately be determined by the recovery path the economy takes.

Table 1.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on radiology

The American College of Radiology (ACR) has endorsed guidance from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to reschedule non-urgent outpatient visits8. This has its greatest impact on screening services (mammography9, lung cancer screening), but the effects will be felt throughout the specialty, including interventional procedures10. Unsurprisingly, imaging volumes are already down11. Outpatient imaging has seen the most precipitous decrease, but lower imaging volumes in the emergency and inpatient setting have also been observed. While these reductions will affect all radiology practices, outpatient focused radiology groups will see the greatest impact in lost revenue. Outpatient imaging has the most favorable revenue profile; patients are more likely to be commercially insured and their disease acuity is lower. Suspension of outpatient imaging is a necessary part of efforts to reduce disease transmission. Thus, outpatient imaging has been stopped before resources would be strained by a surge in COVID-19 cases and before inpatient and emergency settings experience demand related reductions in volume.

Models of COVID-19 case growth and historical hospital resource usage12 can be combined with real world experiences to estimate the length of a crisis response in specific regions. As a point of reference, the most up-to-date modeling from the Connecticut Department of Health projects a peak in regional cases during the first week of May13. Our department began making changes to our operations in the 2nd week of March; nonurgent studies were rescheduled when possible and all urgent outpatient exams were subject to increased scrutiny regarding their necessity. These scheduling changes coincided with alterations to radiologist workflow, staffing schedules and resident participation. Preliminary data from our academic multispecialty radiology practice is consistent with a greater than 70% drop in outpatient imaging. As a comparison, emergent and inpatient imaging volumes have decreased around 50%. These observations are in line with global volume metrics reported by radiology software companies14. Assuming an extra month to recover from peak case growth before easing back into normal operations, this would result in approximately 3 months of dramatically reduced imaging revenue. Ultimately, each practice will be differentially affected based on local public policy, their outpatient imaging volume, technical fee collection, and patient demographics. Radiology practices may be looking at subnormal revenue for a minimum of 3-4 months. Without a pharmaceutical intervention (e.g. COVID-19 vaccine), the potential for disease resurgence15, and differences in the success of mitigation techniques16, the potential timeline for disruption to normal practice could be significantly longer. It is not out of the question that some degree of lockdown could continue for the next 9 months or longer, however, responsible policy decisions coupled with increased testing may allow for some semblance of normal operations even during that period.

How well practices can recover from this nadir will be influenced by payors; patient demographics will again be key. State budgets are incurring significant unexpected expenditures thanks to their COVID-19 response and major revenue shortfalls secondary to lower sales and income tax receipts. Given the stress on state budgets, Medicaid reimbursement rates could see further downward revision, despite augmented federal budgetary support (particularly through the increased Federal Medical Assistance Percentage or FMAP) during this period. Commercial insurers are likely to reap short term benefits from steady premium collections despite decreased benefit claims during the crisis. When elective imaging volumes eventually return to normal, preauthorization processing times may be prolonged as insurers try to clear a backlog of deferred exams.

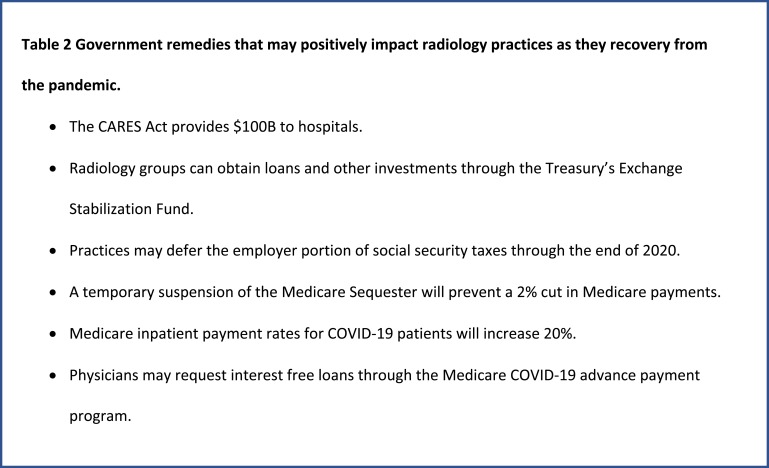

Recovery efforts will require federal assistance (Table 2). The CARES Act17 was signed into law on March 27th, 2020. While the word “radiology” does not appear in the text of the act, multiple provisions may offer relief to radiology practices and their employees. Hospitals are targeted to receive $100B. After paying down increased expenses due to the response, they will presumably try to shore up their outpatient profit centers, radiology included, which experienced significant revenue loss. The initial $30B of this fund is being allocated to hospitals and physician practices in direct proportion to their share of Medicare fee-for-service reimbursement. It is unclear how the remaining funding will be allocated by the Department of Health and Human Services, but guidance has signaled that at least a portion of it will be directed towards providers that rely predominantly on Medicaid18.

Table 2.

Government remedies that may positively impact radiology practices as they recovery from the pandemic.

Radiology groups can obtain loans, loan guarantees, and other investments through the $500B made available through the Treasury’s Exchange Stabilization Fund, provided they meet certain eligibility criteria19. They can also defer paying the employer portion of social security taxes through the end of 2020. A temporary suspension of the Medicare Sequester will prevent a 2% cut in Medicare payments that was previously scheduled to take effect on May 1, 2020. Medicare inpatient payment rates for COVID-19 admissions will increase 20%20. Qualified physicians may also request interest free (if criteria are met) loans through the Medicare COVID-19 advance payment program21. These loan amounts can total up to 3 months of previously collected Medicare payments based on collections from October to December of 2019. Multiple other provisions can provide relief to small businesses, but these are not specific to medicine or Radiology.

It is too early to elucidate the short term and permanent implications for radiology practices that will stem from this pandemic. In the near term, practices should expect significant temporary cuts in revenue. If fortunate enough to not yet be severely affected, practices could consider expanding hours to complete examinations that had been scheduled in the near future. Practices should evaluate their overhead expenses and devise strategies to reduce these on a semi-permanent basis. They will want the ability to quickly restore or exceed baseline capacity once the pandemic subsides, and minimizing disruption to staffing in the short term will be crucial to that end. Staffing challenges can be addressed through a combination of reduced working hours, temporary salary cuts, bonus suspensions, furloughs, and in the direst of circumstances, layoffs. Anecdotally, some organizations are already decreasing salaries and implementing increased scrutiny of new hires, if not explicit freezes on new staff22. Depending on the depth of the recession, recovery of imaging volumes, and potential delays in retirement of more senior radiologists (as was noted following the 2008 financial crisis), the job market for newly minted radiologists may become less appealing.

As we enter recovery in the immediate aftermath of this pandemic, the economy and radiology practices themselves are likely to look different. The overall economy could remain suppressed, but demand for most imaging services should rebound above historical baseline levels as deferred, but necessary, imaging gets scheduled. Some of the revenue from this rebound will be offset by the aforementioned decreased percentage of commercially insured patients. This imaging rebound, and the eventual future steady state of imaging volume are not certainties; much like other industries, Radiology is now an unwilling participant in an experiment of decreased utilization. Will some imaging that was previously routine now be considered superfluous? How will long term physician referral and ordering patterns change?

The pandemic will likely result in long-term or even permanent alterations to Radiology practice. On a micro level, practices could be permanently redesigned as radiologists become more comfortable reading remotely. Large practices will be particularly well suited to expand radiologist hours well beyond the current 9-5 workday with staggered shifts; allowing for higher overall volumes and providing increased flexibility to patients who prefer off hour examinations. Any permanent increase in remote reading will have important effects on resident training and department collegiality. On a macro level, stimulus funding will help some outpatient-focused businesses avoid bankruptcy, but for many it will not be enough. Radiologist income is likely to fall, and some practices may be forced to operate in the red. Market conditions could accelerate corporatization trends in radiology23 as the combination of distressed practices, historically low interest rates, and access to capital create an attractive environment for private equity buyouts. Practices that do survive may more seriously consider true affiliation or merger agreements with large healthcare systems.

The general uncertainty surrounding the extent of the COVID-19 pandemic belies the implications it will have for radiology practices. Incomplete data complicates long term modelling. Haphazard and disjointed public directives may lead to a longer or multiphase crisis response. Antibody testing may uncover far greater prevalence than we understand today. Pharmaceutical interventions could arrive faster than anticipated. The economic recession could turn out to be less deep than anticipated or morph into a full-blown depression. It is our hope that legislators can offer additional help for the unpredictable times ahead. While hospitals have been designated to receive a large sum of funding to date, it is likely short of what is required to prevent hospital and practice bankruptcies. There will be a fourth and probably fifth relief bill passed by congress to address potential shortcomings in the relief to date. Ultimately, it will be a combination of the publicly provided aid and individual managerial decisions by Radiologists that determine what our practice environments look like in 2021 and beyond.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ACA

- Affordable Care Act

- ACR

- American College of Radiology

- CDC

- Center for Disease Control

- FMAP

- Federal Medical Assistance Percentage

- PPE

- Personal Protective Equipment

- CARES Act

- Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act

REFERENCES:

- 1.S&P 500. Economic Research Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SP500; updated Apr 7, 2020. Accessed Apr 7, 2020.

- 2.Unemployment Rate . Economic Research Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE; updated Apr 3, 2020. Accessed Apr 7, 2020.

- 3.Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims . Department of Labor; https://www.dol.gov/ui/data.pdf; Published Apr 9, 2020; Accessed Apr 10, 2020.

- 4.Thompson D. All the Coronavirus Statistics are Flawed; The Atlantic; https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/03/fog-pandemic/608764/; Published Mar 26, 2020. Accessed Apr 7, 2020.

- 5.Krumholz HM. Where Have All the Heart Attacks Gone?; New York Times; https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/well/live/coronavirus-doctors-hospitals-emergency-care-heart-attack-stroke.html?referringSource=articleShare; Published Apr 6, 2020. Accessed Apr 10, 2020.

- 6.Nacoti M, Ciocca A, Giupponoi A, et al. At the Epicenter of the Covid-19 Pandemic and Humanitarian Crises in Italy: Changing Perspectives on Preparation and Mitigation. NEJM Catalyst. 2020.Doi: 10.1056/CAT.20.0080 Published Mar 21, 2020. Accessed Apr 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dranove D, Garthwaite C, Ody C. The Economic Downturn and Its Lingering Effects Reduced Medicare Spending Growth By $4 Billion In 2009–12. Health Affairs 2015; Vol 34, No. 8. Doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0100. Accessed Apr 4, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ACR COVID-19 Clinical Resources for Radiologists. American College of Radiology; https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/COVID-19-Radiology-Resources; Updated Apr 8, 2020. Accessed Apr 8, 2020.

- 9.Society of Breast Imaging Statement on Breast Imaging during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Society of Breast Imaging; https://www.sbi-online.org/Portals/0/Position%20Statements/2020/society-of-breast-imaging-statement-on-breast-imaging-during-COVID19-pandemic.pdf; Published Mar 26, 2020. Accessed Apr 4, 2020.

- 10.A COVID-19 Toolkit for Interventional Radiologists. Society of Interventional Radiology; https://www.sirweb.org/globalassets/aasociety-of-interventional-radiology-home-page/practice-resources/covid-19-toolkit.pdf; Published Mar 16, 2020. Accessed Apr 4, 2020.

- 11.Stempniak M. Mednax sees ‘meaningful’ decline in radiology volume during pandemic, revises revenue forecasts. Radiology Business; https://www.radiologybusiness.com/topics/healthcare-economics/mednax-radiology-volume-coronavirus-covid-19-imaging; Published Mar 25, 2020. Accessed Apr 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.COVID-19 projections assuming full social distancing through May 2020. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; https://covid19.healthdata.org/projections; Updated Apr 8, 2020. Accessed Apr 8, 2020.

- 13.Coronavirus in CT: More Than 1,000 New Cases; Peak for Hartford County Not Expected Until Late May. NBC Connecticut; https://www.nbcconnecticut.com/news/local/governor-to-give-update-on-covid-19-impact-on-connecticut/2249825/; Published Apr 3, 2020. Accessed Apr 4, 2020.

- 14.Walach E. COVID-19 Impact on CT Imaging Volume. Aidoc Blog; https://www.aidoc.com/blog/ct-imaging-volumes-covid19/?utm_content=125056050&utm_medium=social&utm_source=linkedin&hss_channel=lis-xca2IgYf3G; Updated Apr 7, 2020. Accessed Apr 8, 2020.

- 15.Leung K, Wu JT, Liu D, Leung GM. First-wave COID-19 transmissibility and severity in China outside Hubei after control measures, second-wave scenario planning: a modelling impact assessment. Lancet 2020; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30746-7. Published Apr 8, 2020. Accessed Apr 10, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson RM, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth TD. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet 2020; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. Published Mar 9, 2020. Accessed Apr 10, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aid Coronavirus, Relief, and Economic Security Act or the “CARES Act”. 116th Congress; https://www.appropriations.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FINAL%20FINAL%20CARES%20ACT.pdf; Published Mar 27, 2020. Accessed Apr 4, 2020.

- 18.CARES Act Provider Relief Fund. US Department of Health and Human Services; https://www.hhs.gov/provider-relief/index.html; Updated Apr 10, 2020. Accessed Apr 10, 2020.

- 19.CARES Act Offers Loans and Tax Relief to Radiology Practices. American College of Radiology; https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/Advocacy-News/Advocacy-News-Issues/In-the-April-4-2020-Issue/CARES-Act-Offers-Loans-and-Tax-Relief-to-Radiology-Practices; Published Apr 1, 2020. Accessed Apr 4, 2020.

- 20.Summary of CARES Act Supplemental Appropriations / Summary of CARES Act Healthcare Provisions. Association for Medical Imaging Management; https://link.ahra.org/2020/03/27/summary-of-cares-act-supplemental-appropriations/; Published Mar 27, 2020. Accessed Apr 4, 2020.

- 21.CARES Act: Medicare advance payments for COVID-19 emergency. American Medical Association; https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/cares-act-medicare-advance-payments-covid-19-emergency; Updated Apr 6, 2020. Accessed Apr 7, 2020.

- 22.Arnsdorf I. A Major Medical Staffing Company Just Slashed Benefits for Doctors and Nurses Fighting Coronavirus; ProPublica; https://www.propublica.org/article/coronavirus-er-doctors-nurses-benefits; Published Mar 31, 2020. Accessed Apr 9, 2020.

- 23.Fleishon HB, Vijayasarathis A, Pyatt R, Schoppe K, Rosenthal SA, Silva E, III. White Paper: Corporatization in Radiology. JACR 2019; 16:1364–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]