Abstract

Background

Chest CT is used for diagnosis of 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), as an important complement to the reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests.

Purpose

To investigate the diagnostic value and consistency of chest CT as compared with comparison to RT-PCR assay in COVID-19.

Methods

From January 6 to February 6, 2020, 1014 patients in Wuhan, China who underwent both chest CT and RT-PCR tests were included. With RT-PCR as reference standard, the performance of chest CT in diagnosing COVID-19 was assessed. Besides, for patients with multiple RT-PCR assays, the dynamic conversion of RT-PCR results (negative to positive, positive to negative, respectively) was analyzed as compared with serial chest CT scans for those with time-interval of 4 days or more.

Results

Of 1014 patients, 59% (601/1014) had positive RT-PCR results, and 88% (888/1014) had positive chest CT scans. The sensitivity of chest CT in suggesting COVID-19 was 97% (95%CI, 95-98%, 580/601 patients) based on positive RT-PCR results. In patients with negative RT-PCR results, 75% (308/413) had positive chest CT findings; of 308, 48% were considered as highly likely cases, with 33% as probable cases. By analysis of serial RT-PCR assays and CT scans, the mean interval time between the initial negative to positive RT-PCR results was 5.1 ± 1.5 days; the initial positive to subsequent negative RT-PCR result was 6.9 ± 2.3 days). 60% to 93% of cases had initial positive CT consistent with COVID-19 prior (or parallel) to the initial positive RT-PCR results. 42% (24/57) cases showed improvement in follow-up chest CT scans before the RT-PCR results turning negative.

Conclusion

Chest CT has a high sensitivity for diagnosis of COVID-19. Chest CT may be considered as a primary tool for the current COVID-19 detection in epidemic areas.

Keywords: 2019-nCoV pneumonia, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, chest CT imaging, diagnostic value, positive rate

Summary

Chest CT had higher sensitivity for diagnosis of COVID-19 as compared with initial reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from swab samples in the epidemic area of China.

Key Points

■ The positive rates of RT-PCR assay and chest CT imaging in our cohort were 59% (601/1014), and 88% (888/1014) for the diagnosis of suspected patients with COVID-19, respectively.

■ With RT-PCR as a reference, the sensitivity of chest CT imaging for COVID-19 was 97% (580/601). In patients with negative RT-PCR results but positive chest CT scans (n=308 patients), 48% (147/308) of patients were re-considered as highly likely cases, with 33% (103/308) as probable cases by a comprehensive evaluation.

■ With analysis of serial RT-PCR assays and CT scans, 60% to 93% of patients had initial positive chest CT consistent with COVID-19 before the initial positive RT-PCR results. 42% of patients showed improvement of follow-up chest CT scans before the RT-PCR results turning negative.

Introduction

Since December 2019, a number of cases of “unknown viral pneumonia” related to a local Seafood Wholesale Market were reported in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China (1). A novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was suspected to be the etiology with Phinolophus bat as the alleged origin (2). In just two months, the virus has spread from Wuhan to the whole China, and another 33 countries. By 24:00 on February 24, accumulative 77,658 confirmed cases with 9,126 severe cases and 2,663 deaths were documented in China (3), and 2,309 confirmed cased with 33 death were reported in other countries (including Japan, Korea, Italy, Singapore, Iran as the top five countries). As of 24:00 on February 11, a total of 1,716 confirmed cases and 1,303 clinically diagnosed cases of medical personnel were reported from 422 medical institutions, of which 5 died, accounting for 0.4% of the nationwide deaths during the same time period (4).

In absence of specific therapeutic drugs or vaccines for 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), it is essential to detect the diseases at an early stage, and immediately isolate the infected person from the healthy population. According to the latest guideline of Diagnosis and Treatment of Pneumonitis Caused by 2019-nCoV (trial sixth version) published by the China government (5), the diagnosis of COVID-19 must be confirmed by the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or gene sequencing for respiratory or blood specimens, as the key indicator for hospitalization. However, with limitations of sample collection and transportation, and kit performance, the total positive rate of RT-PCR for throat swab samples was reported to be about 30% to 60% at initial presentation (6). In the current emergency, the low sensitivity of RT-PCR implies that many COVID-19 patients may not be identified and may not receive appropriate treatment in time; such patients constitute a risk for infecting a larger population given the highly contagious nature of the virus. Chest CT, as a routine imaging tool for pneumonia diagnosis, is relatively easy to perform and can produce fast diagnosis. In this context, chest CT may provide benefit for diagnosis of COVID-19. As recently reported, chest CT demonstrates typical radiographic features in almost all COVID-19 patients, including ground-glass 4 opacities, multifocal patchy consolidation, and/or interstitial changes with a peripheral distribution (7). Those typical features were also observed in patients with negative RT-PCR results but clinical symptoms. It has been noted in small-scale studies that the current RT-PCR testing has limited sensitivity, while chest CT may reveal pulmonary abnormalities consistent with COVID-19 in patients with initial negative RT-PCR results (8, 9).

To better understand the diagnostic value of chest CT compared with RT-PCR testing, we report the results of chest CT in comparison to the initial and serial RT-PCR results in 1014 patients with suspected COVID-19.

Materials and Methods

Patients and data sources of RT-PCR results

The institutional review board of our hospital (Tongji Hospital of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China) approved this retrospective study and written informed consent was waived. From January 6 to February 6, 2020, a total of 1049 patients (mean age, 51 ± 15 years; 46% male) who were suspected of novel coronavirus infection and underwent both chest CT imaging and laboratory virus nucleic acid test (RT-PCR assay with throat swab samples) were retrospectively enrolled in our hospital (Figure 1). The RT-PCR results were extracted from the patients’ electronic medical records in our hospital information system (HIS). The RT-PCR assays were performed by using TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Kits from Shanghai Huirui Biotechnology Co., Ltd or Shanghai BioGerm Medical Biotechnology Co., Ltd, both of which have approved use by the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA). For patients with multiple RT-PCR assays, the repeated testing conducted up to and including 3 days after the initial test was adopted as confirmation of diagnosis. Repeated testing more than 3 days after the initial RT PCR Test was used to analyze conversion of RT-PCR results, in correlation with the chest CT scan(s).

Figure 1:

Flowchart of this study.

RT-PCR= reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

For patients with multiple RT-PCR assays, the diagnosis of COVID-19 was confirmed when any one of the nucleic acid test results was positive. If a patient had multiple 5 chest CT scans, we included the scan with shortest interval (less than or equal to 7 days) to compare with the RT-PCR assay for the analysis of diagnostic performance; any other chest CT scans in the same patient were used to assess the temporal change of the disease. Patients were excluded when the time-interval between chest CT and the RT-PCR assay was longer than 7 days.

Chest CT protocols

All images were obtained on one of the three CT systems (uCT 780, United Imaging, China; Optima 660, GE, America; Somatom Definition AS+, Siemens Healthineers, Germany) with patients in supine position. The main scanning parameters were as follow: tube voltage = 120 kVp, automatic tube current modulation (30 - 70 mAs), pitch = 0.99 - 1.22 mm, matrix = 512 × 512, slice thickness = 10 mm, field of view = 350 mm × 350 mm. All images were then reconstructed with a slice thickness of 0.625 - 1.250 mm with the same increment.

Image analysis

Two radiologists (T.A. and Z.L.Y. with 12 and 3 years of experience in interpreting chest CT imaging, respectively), who were blinded to RT-PCR results, reviewed all chest CT images and decided on positive or negative CT findings by consensus. The epidemiological history and clinical symptoms (fever and/ dry cough) were available for both readers. The radiologists classified the chest CT as positive or negative for COVID-19. The radiologists also described main CT features (ground-glass opacity, consolidation, reticulation/thickened interlobular septa, nodules), and lesion distribution (left, right or bilateral lungs).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL). Continuous variables were displayed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables were reported as counts and percentages.

Using RT-PCR results as reference, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy of chest CT imaging were calculated. A 95% confidence interval was provided by the Wilson score method. The performance of chest CT for identifying COVID-19 in different age groups (<60 years and ≥ 60 years) and by gender was compared by the Chi-square test.

For patients with negative RT-PCR tests but positive CT results, follow-up chest CT images were re-reviewed to further confirm the imaging diagnosis if available. Clinical symptoms, typical imaging features on the initial chest CT scan, and dynamic changes on the serial follow-up chest CT scans were combined to classify the patients into highly likely cases, probable cases and uncertain cases for those without serial CT scans: (1) highly likely cases, defined as patients with clinical symptoms (fever, cough, fatigue and/or shortness of breath), and typical CT features with dynamic changes (obvious progression or improvement in a short time) on serial CT scans; (2) probable cases, defined as patients with clinical symptoms aforementioned and typical CT features, but stable on the follow-up CT scans, or without follow-up CT scans; (3) uncertain cases defined as patients with only one positive chest CT scan, indicating viral pneumonia.

As to patients with multiple RT-PCR assays (with time-interval of 4 days or more), the conversion of RT-PCR test results (negative to positive, and positive to negative, respectively) was analyzed in correlation with the corresponding serial chest CT scans if available. Change in RT PCR and CT may reflect viral proliferation or clearance in infected patients.

Results

General description

Thirty-five patients were excluded when the time-interval between chest CT and the RT-PCR assay was longer than 7 days. After exclusion of these patients, 1,014 patients (mean age, 51 ± 15 years; 46% [467/1014] men) were available for analysis. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of our study. Of 1014 patients, 601 had positive and 413 had negative RT-PCR results with a positive rate of 59% (601/1014) (95% confidence interval [CI], 56% - 62%) (Figure 1). Of 601 patients with positive RT-PCR results, 97% (580/601) had positive chest CT scans. Of 413 patients with negative RT-PCR result, 75% (308/413) had positive chest CT scans.

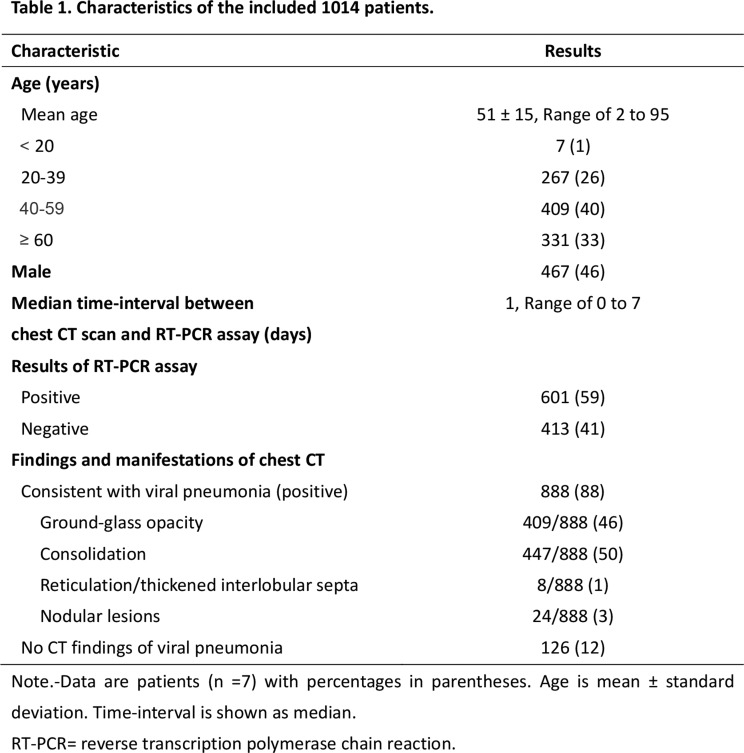

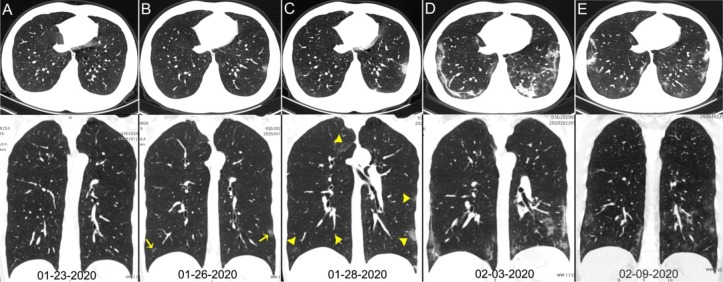

The median time interval between the paired chest CT exams and RT-PCR assays was 1 day (range of 0-7 days). 88% (888/1014) (95% CI, 86% - 90%) of patients had positive chest CT findings. The main chest CT findings were ground-glass opacity (46% [409/888]) and consolidations (50% [447/888]) (Table 1) (Figure 2-4). Most patients (90% [801/888]) had bilateral chest CT findings.

Table 1:

Characteristics of the included 1014 patients.

Figure 2:

Chest CT images of a 29-year-old man with fever for 6 days. RT-PCR assay for the SARS-CoV-2 using a swab sample was performed on February 5, 2020, with a positive result. (A column) Normal chest CT with axial and coronal planes was obtained at the onset. (B column) Chest CT with axial and coronal planes shows minimal ground-glass opacities in the bilateral lower lung lobes (yellow arrows). (C column) Chest CT with axial and coronal planes shows increased ground-glass opacities (yellow arrowheads). (D column) Chest CT with axial and coronal planes shows the progression of pneumonia with mixed ground-glass opacities and linear opacities in the subpleural area. (E column) Chest CT with axial and coronal planes shows the absorption of both ground-glass opacities and organizing pneumonia.

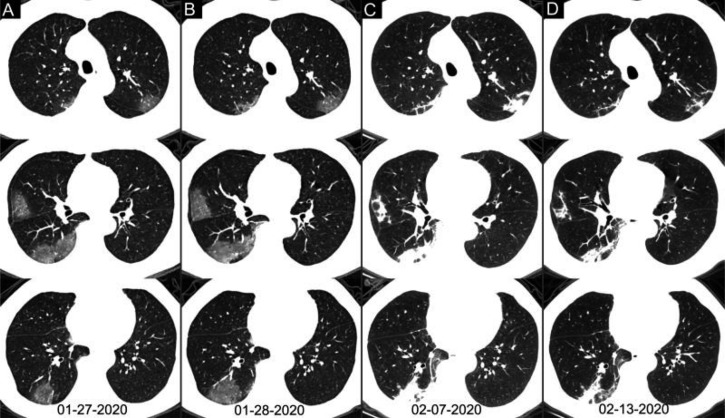

Figure 4:

Chest CT images of a 46-year-old woman with fever for 4 days. The result of RT-PCR assay for the SARS-CoV-2 using a swab sample was positive on February 4, 2020 and was negative on February 12. Three chest CT scans obtained from January 27 (column A), February 2 (column C) and February 09, 2020 (column C) show the gradual absorption of bilateral ground-glass opacities and linear consolidation.

Figure 3:

Chest CT images of a 34-year-old man with fever for 4 days. Positive result of RT-PCR assay for the SARS-CoV-2 using a swab sample was obtained on February 8, 2020. (row A) Chest CT with lesion-magnified coronal and sagittal planes shows a nodule with reversed halo sign in the left lower lobe (yellow box) at the early stage of the pneumonia. (row B) Chest CT with different axial planes and coronal reconstruction shows bilateral multifocal ground-glass opacities. The nodular opacity resolved.

Performance of chest CT in diagnosing COVID-19

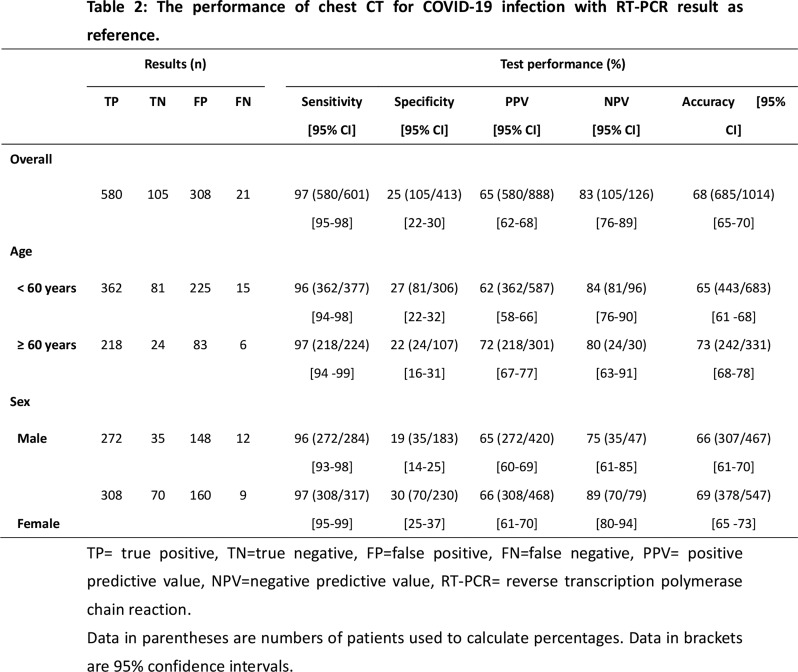

There were 888 patients with positive chest CT findings (< 60 years, n ≥ 587; = 60 years, n = 301; 420 men and 468 women). With RT-PCR results as reference, the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy of chest CT in indicating COVID-19 infection were 97% (95% CI 95-98%, 580/601 patients), 25% (95% CI 22-30%, 105/413 patients) and 68% (95%CI 65-70%, 685/1014 patients), respectively.

The performance of chest CT in diagnosing COVID-19 in different age and sex groups is reported in Table 2. The positive predictive values (PPV) and accuracy of chest CT in diagnosing COVID-19 were higher in patients ≥ 60 years than that in patients < 60 years (p = 0.001 and 0.009, respectively); and no difference existed for sensitivity, specificity and negative predictive value (NPV) (p = 0.40, 0.41 and 0.58, respectively). The specificity and NPV of chest CT in diagnosing COVID-19 were greater for women than that for men (p = 0.009 and 0.04, respectively); and no difference existed for sensitivity, PPV and accuracy (p = 0.36, 0.74 and 0.25, respectively).

Table 2:

The performance of chest CT for COVID-19 infection with RT-PCR result as reference.

Discrepant findings between chest CT and RT-PCR

21 patients (mean age, 46 ± 24 years, 57% male) had positive RT-PCR results but without lesions on initial chest CT. The chest CT images of 308 patients (mean age, 47 ± 14 years, 48% man) suggested COVID-19, while their RT-PCR assays from throat swab samples were negative (Figure 5 and 6). Of 308 patients, most (83% [256/308]) had bilateral lung lesions consisting of ground-glass opacities (41% [126/308])) and 8 consolidations (56% [172/308]) on chest CT.

Figure 5:

Chest CT images of a 62-year-old man with fever for 2 weeks, and dyspnea for 1 day. Negative results of RT-PCR assay for the SARS-CoV-2 using a swab samples were obtained on February 3 and 11, 2020, respectively. (column A) Chest CT with multiple axial images shows multiple ground-glass opacities in the bilateral lungs. (column B) Chest CT with multiple axial images shows enlarged multiple ground-glass opacities. (column C) Chest CT with multiple axial images shows the progression of the disease from ground-glass opacities to multifocal organizing consolidation. (D column) chest CT with multiple axial images shows partial absorption of the organizing consolidation.

Figure 6:

Chest CT images of a 63-year-old woman with fever for 11 days. Negative results of RT-PCR assay for the SARS-CoV-2 using a swab samples were obtained on February 2 and 11, 2020, respectively. (A-C) Chest CT scans show typical mixed ground-glass opacities and multifocal consolidation shadows in bilateral lungs without evidence of resolution without resolution over 16 days.

Based on the analysis of clinical symptoms, CT features and serial CT scans if available, 48% (147/308) of patients were considered as highly likely cases, 33 % (103/308) as probable cases and 19 % (58/308) as uncertain cases.

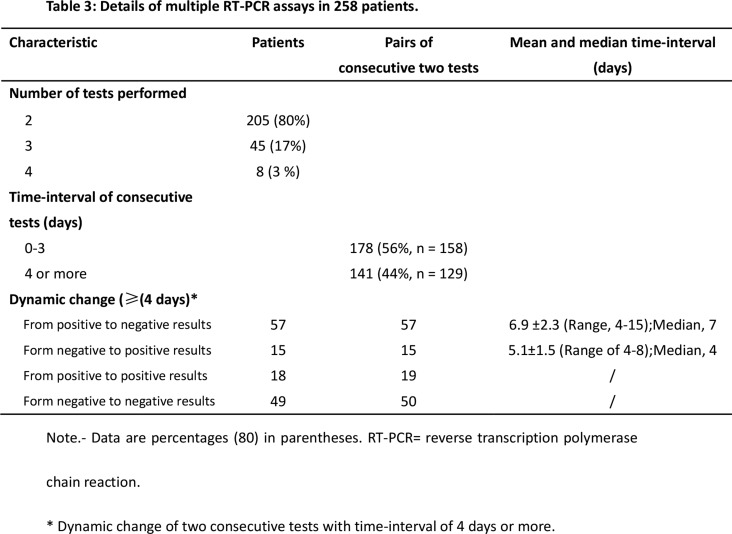

Analysis of multiple RT-PCR assays and serial chest CT scans

A total of 258 patients underwent multiple RT-PCR assays (Table 3). For patients with follow-up RT-PCR testing (with time-interval of more than 3 days), the mean interval time between initial negative to positive RT-PCR results was 5.1 ± 1.5 days with a range of 4-8 days and a median of 4 days (n = 15). The mean interval time between initial positive RT-PCR testing and subsequent negative change was 6.9 ± 2.3 days with a range of 4-15 days and the median was 7 days (n = 57). In the subgroup of negative to positive RT-PCR results, 67% (10/15) cases showed initial positive chest CT imaging before the initial negative RT-PCR results; and 93% (14/15) cases showed that the initial chest CT had typical imaging features consistent with COVID-19 prior (or parallel) to the initial positive RT-PCR results, with a median time-interval of 8 days (range, 0 – 21 days). In the subgroup of positive to negative RT-PCR results, 60% (34/57) cases showed the initial chest CT had typical imaging features consistent with COVID-19 prior (or parallel) to the initial positive RT-PCR results, with a median time-interval of 6 days (range, 0 - 27 days); and almost all patients (56/57) had initial positive chest CT scans before or within 6 days of the initial positive RT-PCR results. In addition, 42% (24/57) cases showed improvement of follow-up chest CT scans before the RT-PCR results turning negative; and only 3.5% (2/57) cases showed disease progression on the follow-up CT scans after the RT-PCR results turning negative (Figure 7).

Table 3:

Details of multiple RT-PCR assays in 258 patients.

Figure 7:

Analysis of serial RT-PCR assays in correlation with serial chest CT scans. (A) The subgroup of positive to negative RT-PCR results (n = 57). (B) The subgroup of negative to positive RT-PCR results (n = 15). The horizontal axis is the time point of initial chest CT and follow-up chest CT scans relative to the time point of the consecutive two RT-PCR tests (before positive RT-PCR, negative numbers; after RT-PCR, positive numbers).

Discussion

Early diagnosis of 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is crucial for disease treatment and control. Compared to RT-PCR, chest CT imaging may be a more reliable, practical, and rapid method to diagnose and assess COVID-19, especially in the epidemic area. With RT-PCR results as reference in 1014 patients, the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy of chest CT in indicating COVID-19 infection were 97% (580/601), 25% (105/413) and 68% (685/1014), respectively. The positive predictive value and negative predictive value were 65% (580/888) and 83% (105/126), respectively.

According to current diagnostic criterion, viral nucleic acid test by RT-PCR assay plays a vital role in determining hospitalization and isolation for individual patients. However, its lack of sensitivity, insufficient stability, and relatively long processing time were detrimental to the control of the disease epidemic. In our study, the positive rate of RT-PCR assay for throat swab samples was 59% (95%CI, 56%-62%) which was consistent with previous report (30 - 60%) (6). In addition, a number of any external factors may affect RT-PCR testing results including sampling operations, specimens source (upper or lower respiratory tract), sampling timing (different period of the disease development) (6), and performance of detection kits. As such, the results of RT-PCR tests must be cautiously interpreted.

Chest CT is a conventional, non-invasive imaging modality with high accuracy and speed. Based on available data published in recent literature, almost all patients with COVID-19 had characteristic CT features in the disease process (8, 10-13), such as different degrees of ground-glass opacities with/without crazy-paving sign, multifocal organizing pneumonia, and architectural distortion in a peripheral distribution. From our study, in addition, about 60% (34/57) cases had typical CT features consistent with COVID-19 prior (or parallel) to the initial positive RT-PCR results, and almost all patients (56/57) had initial positive chest CT scans before or within 6 days of the initial positive RT-PCR results. This indicates that CT imaging can be very useful in early detection of suspected cases.

In this study, 97% of patients confirmed by RT-PCR assays showed positive findings on chest CT, which was higher than that reported by Zhong et al.(76.4%) (14). A likely explanation is that patients in this study were all from the largest hospital in Wuhan, China, the central area of the outbreak of COVID-19. In this context, radiologists were more likely to make a diagnosis of COVID-19 when typical CT features were found. Given the sensitivity of chest CT (hence its value to prevent further spread of disease), a clinical diagnosis criteria based on typical CT imaging features was temporarily adopted in the revised 5th edition of the Guideline of Diagnosis and Treatment, which was only applicable in Hubei Province, China (15). Besides, Pan et al. demonstrated that multiple re-examinations of chest CT can accurately reflect the disease evolution and monitor the treatment effect (12). We also observed 42% (24/57) of patients showed improvement in follow-up chest CT scans, which was earlier than the RT-PCT results turning negative. Only two of 57 (3.5%) patients showed progression on follow-up chest CT scans after RT-PCR test results turned negative.

For patients with negative RT-PCR tests, more than 70% had typical CT manifestations. On the one hand, due to the overlap of CT imaging features between COVID-19 and other viral pneumonia, false-positive cases of COVID-19 can be identified on chest CT. Nevertheless, considering the rapidly spreading epidemic of COVID-19, the priority was to identify any suspicious CT case in order to isolate the patients and administer appropriate treatment. In the context of emergency disease control, some false-positive cases may be acceptable. On the other hand, given the relatively low positive rate of RT-PCR assay, some “false-positive” cases on CT may indeed be “true-positive” if RT-PCR assay is an imperfect standard of reference. In fact, from the results of this study, about 81% of the patients with negative RT-PCR results but positive chest CT scans were re-classified as highly likely or probable cases with COVID-19, by the comprehensive analysis of clinical symptoms, typical CT manifestations, and dynamic CT follow-ups. Based on serial RT-PCR test and CT scans, 90% (14/15) of patients had initial positive chest CT consistent with COVID-19 prior (or parallel) to the initial positive RT-PCR results. As such, it can be speculated that those negative RT-PCR results could be problematic. In patients with negative RT-PCR tests, a combination of exposure history, clinical symptoms, typical CT imaging features, and dynamic changes should be used to identify COVID-19 with higher sensitivity.

There are several limitations in the present study. First, by using RT-PCR assays with relatively low positive rate as reference, the sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19 may be overestimated while the specificity underestimated. In epidemic area, negative RT-PCR but positive CT features can still be highly suggestive of COVID-19. This has important clinical and societal implications; rapid detection with high sensitivity of viral infection may allow better control of viral spread. A second limitation is that clinical and laboratory data were limited during this urgent period when regional hospitals were overloaded. Nevertheless, the results reported in this work from the center of the epidemic area should supply important information regarding the value of CT and RT-PCR in combating the prevalent disease.

In conclusion, chest CT imaging has high sensitivity for diagnosis of COVID-19. Our data and analysis suggest that chest CT should be considered for the COVID-19 screening, comprehensive evaluation, and following-up, especially in epidemic areas with high pre-test probability for disease.

APPENDIX

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: W.Z.L. is employee of Julei Technology Company. And the data of this study is analyzed and controlled by authors who are not the employees of medical industry.

Tao Ai and Zhenlu Yang contributed equally to this work.

Abbreviations:

- RT-PCR

- reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- NCP

- novel coronavirus pneumonia

- PPV

- positive predictive value

- NPV

- negative predictive value

Reference

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020. 395(10223):497-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected: interim guidance. Jan 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China . http://www.nhc.gov.cn (Assessed on February 25th, 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team, Chinese Center of Disease Control and Prevention . The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Chinese journal of epidemiology. 2020. 41(2):145-151. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. (In Chinese with English Abstract). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.General Office of National Health Committee . Notice on the issuance of a program for the diagnosis and treatment of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (trial sixth edition) (2020-02-18). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/8334a8326dd94d329df351d7da8aefc2.shtml?from=timeline (accessed Feb 24, 2020).

- 6.Yang Y, Yang M, Shen C, et al. Evaluating the accuracy of different respiratory specimens in the laboratory diagnosis and monitoring the viral shedding of 2019-nCoV infections. 2020. 10.1101/2020.02.11.20021493. [DOI]

- 7.Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X, et al. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Radiology 2020. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang P, Liu T, Huang L, et al. Use of chest CT in combination with negative RT-PCR assay for the 2019 novel coronavirus but high clinical suspicion. Radiology 2020. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2020200330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie X, Zhong Z, Zhao W, et al. Chest CT for typical 2019-nCoV pneumonia: relationship to negative RT-PCR testing. Radiology 2020. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2020200343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lei J, Li J, Li X, et al. CT imaging of the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology 2020. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2020200236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi H, Han X, Zheng C. Evolution of CT manifestations in a patient recovered from 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Radiology 2020. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2020200269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan F, Ye T, Sun P, et al. Time course of lung changes on chest CT during recovery from 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia. Radiology 2020. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2020200370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan Y, Guan H, Zhou S, et al. Initial CT findings and temporal changes in patients with the novel coronavirus pneumonia (2019-nCoV): a study of 63 patients in Wuhan, China.Eur Radiol. 2020. DOI: 10.1007/s00330-020-06731-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. 2020 10.1101/2020.02.06.20020974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.General Office of National Health Committee . Notice on the issuance of a program for the diagnosis and treatment of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (trial revised fifth edition) (2020-02-8). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/d4b895337e19445f8d728fcaf1e3e13a.shtml (accessed Feb 24, 2020).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.