Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic presents an unprecedented challenge to the health care systems of the world. In Singapore, early experiences of the radiology community on managing this pandemic was shaped by lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in 2003. This article surveys the operational responses of radiology departments from six public hospitals in Singapore.

© RSNA, 2020

Summary

This article provides a summary of the preparations made by the radiology departments in six public hospitals in Singapore to battle the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

The integral role of radiology in the early diagnosis and subsequent management of an infectious disease outbreak has been well described and is epitomized by the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic of 2003 (1). China, Hong Kong, Vietnam, and Singapore were the most severely affected countries by SARS, and in Singapore, there were 238 cases and 33 deaths. The experience of dealing with the epidemic was a pivotal moment in the development of our nation’s health care system, which was stressed and tested to its limits. Radiology departments within hospitals were challenged for reconfiguring their setup and work processes in response to the needs of frontline imaging services, thereby aiding rapid diagnosis. One radiology department in Singapore was also a site of cross-infection, an incident that highlighted the importance of protecting and securing imaging resources during an outbreak (2).

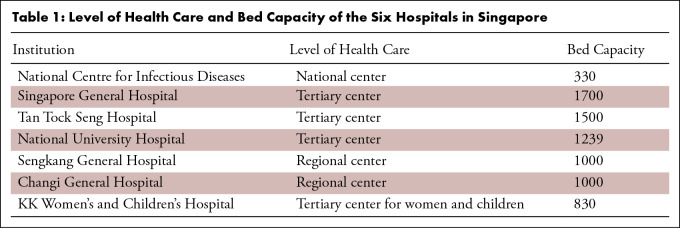

In Singapore, the health care system is organized into three clusters, each helmed by a tertiary-level hospital and supported by several regional hospitals and primary care polyclinics (3). There are also national institutes, such as the new purpose-built National Centre for Infectious Disease, which provides national-level infectious disease surveillance and coordination, and the Kandang Kerbau Women’s and Children’s Hospital dedicated for pediatric patients (Table 1). For the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak (4), the infectious disease teams and isolation facilities within each hospital help manage their own suspected and confirmed COVID-19 cases as patients present. The National Centre for Infectious Disease manages all nonhospital referrals, whereas pediatric referrals are directed to the Kandang Kerbau Women’s and Children’s Hospital (5). Each of these hospitals has an organic radiology department with a full suite of general diagnostic imaging capabilities and varying levels of subspecialty, nuclear medicine, and interventional radiology capabilities.

Table 1:

Level of Health Care and Bed Capacity of the Six Hospitals in Singapore

With the lessons learned during the SARS outbreak, most radiology departments in Singapore have, where possible, incorporated outbreak preparedness into their work processes and protocols (6). To this end, newer facilities including the National Centre for Infectious Disease have been designed and equipped with imaging services that are integrated with the institutions’ overall infection control and outbreak containment strategies. Regular drills and tabletop exercises conducted by the various institutions’ outbreak management teams all include and involve radiology departments.

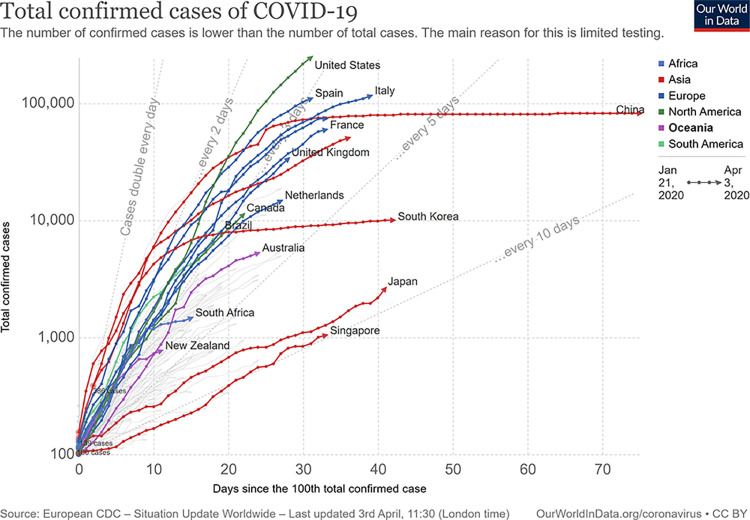

Following the World Health Organization’s (WHO) declaration of the COVID-19 epidemic as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, 2020, the outbreak continued to unfold, and on March 11, 2020, it was classified as a pandemic by the WHO (7). Singapore had its first COVID-19 case diagnosed on January 23, 2020, and has since treated 1000 cases as of April 1, 2020. Both imported cases and local transmission of COVID-19 persist in Singapore as we continue to screen for and manage these cases (8). The overall strategy of Singapore in dealing with the outbreak aims at flattening the epidemic curve (Figure) (9) such that hospitals do not get overwhelmed by a surge of cases. This is achieved by isolation of confirmed cases, contact tracing, and physical distancing to break the chain of transmission (10).

Figure:

Epidemic curve of COVID-19 cases by country. (Reprinted under a CC BY 4.0 license from reference 9).

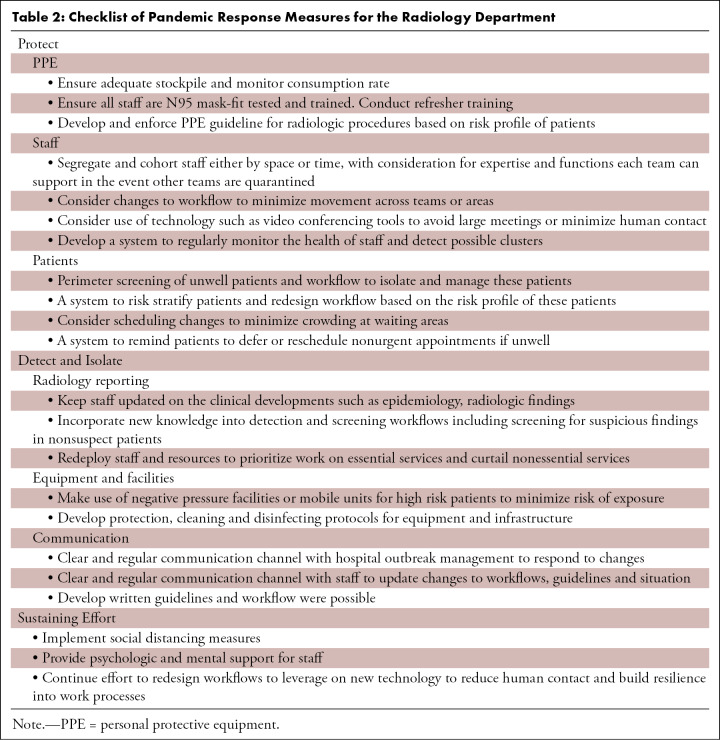

Unlike during the SARS outbreak in 2003, when Tan Tock Seng Hospital was designated a “SARS hospital,” all hospitals in Singapore now collaborate in managing patients with COVID-19. This article surveys and details the wide-ranging operational responses of the radiology departments in six public hospitals that are treating patients with COVID-19 in Singapore as they geared up to meet this challenge (Table 2).

Table 2:

Checklist of Pandemic Response Measures for the Radiology Department

Immediate Response–Protect

In the earliest phase of the outbreak, all contingency plans were reviewed, and an effort was made to conserve, secure, and protect all available staff and resources. In one of the hospitals, a small task force comprising key appointment holders was constituted to coordinate the outbreak response. In the initial phase, the task force met daily to review staffing, information update, operational plans, equipment status, and training and safety plans. Key members were also emplaced into the hospital outbreak response team and infectious disease teams to obtain firsthand information and coordinate measures in response to the rapidly changing situation.

Personal Protective Equipment and Infection Control Measures

Hospital personal protective equipment (PPE) stockpiles were immediately released and made available to all frontline staff. With global stocks in short supply, a few sites rationed their surgical masks to nonclinical staff. Guidance on PPE usage was provided by the Ministry of Health of Singapore, which took a risk-based approach in developing the guidelines. Usage of different PPE types is dependent on (a) the national framework for disease response or Disease Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) level , (b) the infection risk areas within the hospital, and (c) the type of procedures performed (11). Each hospital’s infection control committee issued a local set of PPE recommendations according to these guidelines. A full set of PPE consists of a cap, goggles or a face shield, an N95 mask, and a gown, which are worn by frontline staff when interacting with suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19. Wearing a surgical mask is a basic requirement when one is working in a clinical area.

The use of a powered air purifier respirator is not mandatory in most instances. If available, it is often reserved for aerosol-generating procedures or in situations where prolonged N95 mask use cannot be tolerated. Following the experience of SARS, our hospitals carry out regular mask fitting exercises for all staff and have made instructional videos on donning and doffing of PPE available online. Already a feature in all institutions, the importance of hand hygiene was re-emphasized and frequent reminders were sent out in an effort to improve on compliance. Sanitizing hand rubs were also made widely available throughout the department. In some hospitals, portable high-efficiency particulate air filters were also placed at staff areas to minimize potential transmission. Other measures include a “mask-up” policy within both the clinical and nonclinical areas.

It is vital from the outset to have departmental infection prevention liaison officers working closely with infectious disease physicians or members of the hospital’s infection control team to provide clarity on what constitutes adequate and appropriate PPE. In one hospital, there is even a daily safety walkabout by departmental infection prevention liaison officers and senior staff to follow up on infection control policies.

Staff Segregation and a New Work Environment

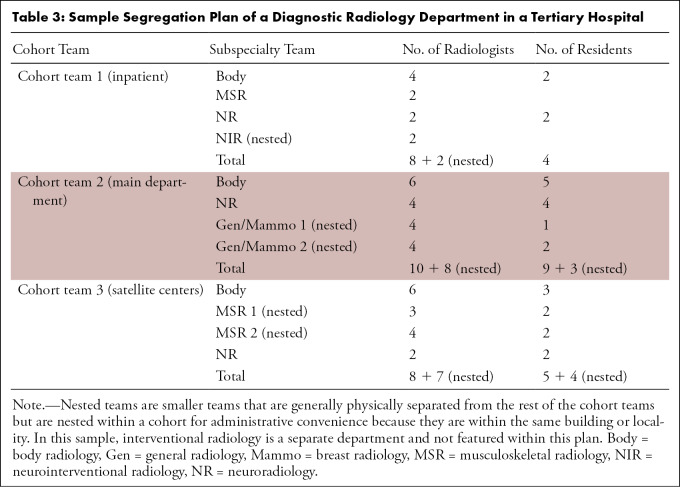

To avoid disruption in staffing, should cross-transmission occur, the policy of staff segregation or cohorting was implemented in all hospitals. Each professional group was divided into fully functioning units considering the need to create an optimal mix of available subspecialty expertise. These units were then separated by either time or location within the department or hospital (12). For example, in a particular tertiary hospital, the diagnostic radiology department was segregated into three cohort teams (Table 3) with main subspecialties divided and distributed into these cohorts. It considers the physical limitations and functional requirements in each location, such as the number of workstations available or inpatient imaging support exclusively by a designated “hot” team. Residents were similarly distributed into each team considering their training plan. Smaller subspecialties such as breast radiology or neurointerventional radiology may be divided into smaller units nested within a cohort but segregated from it. Each cohort team and nested team is duplicated and could therefore function independently if required. The small neurointerventional radiology team is duplicated at the national level across several hospitals for business continuity because of its limited strength.

Table 3:

Sample Segregation Plan of a Diagnostic Radiology Department in a Tertiary Hospital

In another example, the interventional radiology department was segregated into two functional hybrid teams depending on the physical location of the interventional suites. Each team consists of members across the professional domains (eg, doctors, nurses, radiographers, etc) capable of performing the full range of procedures.

To further enable physical segregation, most teams found it useful to have alternative radiology work areas or intrahospital satellites with network-ready access points installed for picture archiving and communication system workstations. Unused offices were also converted into radiology workspaces in several instances. These newly installed or reconfigured workstations would be spaced at least 2 meters apart, and users are advised to wipe down with disinfectant before and after each use. Remote reporting or teleradiology through virtual private network access is a top-drawer plan for most hospitals. When the need arose for some centers, the existing infrastructure facilitated rapid operationalization by hospital IT professionals. The challenges with teleradiology include the need to source for suitable high-resolution reporting workstations and the presence of reliable and secure network connectivity.

In temporal segregation, the existing staff is divided into two or more groups, which will then work in shifts. The department’s workload will then be reduced by postponing nonurgent cases to accommodate the reduced staff. In smaller departments, physical segregation is deemed to be less onerous and hence more feasible when compared with a time-based shift system. To overcome limitations in staff numbers, one hospital utilized a staggered shift system, which allows it to meet its commitment to around-the-clock 1-hour chest radiography reporting turnaround time, while simultaneously minimizing fatigue and preventing staff burnout. Mixed temporal and physical segregation policies were employed in another hospital, where two teams worked in weekly shifts, alternating between on-site clinical and procedural-based coverage followed by off-site or home-based reporting.

There has been a concerted nationwide effort to consolidate our medical staff at this crucial time. Prospective nonessential leave was cancelled en bloc with prior in-principle approved leave allowed only on a case-by-case basis. The number of staff members affected by the lockdown occurring in China was fortunately small, and they were able to return to work well after an enforced 2 weeks’ leave of absence. As an established practice since SARS, all staff members are required to monitor their body temperatures twice daily and have them logged onto a national health care online database. Occupational health clinics are available for those who feel unwell, requiring further assessment and treatment.

In line with national policy directions, “social distancing” is encouraged within and outside the workplace to minimize chances of cross-infection. It was a difficult policy to implement because of the busy and often crowded nature of typical radiology workspaces. Across all institutions, deliberate efforts have been made to curtail nonessential meetings. Meeting agendas have also been shortened. When possible, technological adjuncts in the form of video conferencing using dedicated software (eg, Zoom; Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, Calif; WebEx; Cisco Systems, Santa Clara, Calif) are employed. The latter proved particularly useful in the conduct of residency teaching sessions, especially because residents from different institutions were prohibited to congregate. Lecture slides and teaching material have been made available online. In some hospitals, clinic-radiologic rounds have been exclusively conducted by using the Personal Data Protection Act–compliant (13) video conferencing platforms (eg, WebEx). For those hospitals where physical clinic-radiologic rounds continued, attendees must wear masks, and the rounds were held in larger rooms with better ventilation and seats that are spaced further apart. In a similar fashion, social distancing measures have also been extended to the staff pantry in a few centers. Staff have been oriented to sit further apart during staggered lunch breaks, and casual conversation is kept to a minimum. Pantry windows have also been opened for improved ventilation during mealtimes.

Protecting Patients

In a departure from what was practiced during SARS, patient screening is now mostly performed at main entrances of the hospitals instead of at the entrances of radiology departments (14). The key components of screening entail stringent temperature monitoring via thermal scanners, detailed travel history logs, and enforcement of access controls. Accompanying family members are discouraged from crowding in the waiting areas of the radiology departments. Where possible, start times for imaging scans have also been scheduled further apart to ensure temporal segregation. Physical segregation for patients is achieved by reconfiguring separate access routes for inpatients and outpatients. This serves to minimize potential cross-infection between these groups of patients. Preappointment text messages are also sent to remind patients to reschedule their appointments if they are unwell.

Within the newest operational hospital, radiofrequency identification tags used in staff identification passes and existing smart patient tracking technology have been put to use in access control for staff and maintaining visibility on unauthorized patient movements. With the availability of electronic data on staff and patients’ location at any particular time, the process of contact tracing in the event of diagnosis of a positive COVID-19 case is expedited and performed with increased precision.

Detect and Isolate

Equipment and Facilities

The use of CT scan as a screening tool is a novel approach and has been trialed during the COVID-19 outbreak in China, with a reported detection rate of 98% for initial CT scan versus 71% for the first reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction test (15). However, this move was prompted partly by the lack of test kits during the early stages of the outbreak and also the fairly high number of false-negative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction results. The use of routine screening CT for COVID-19 pneumonia is currently not endorsed by most radiology societies (16,17).

The main imaging modality of choice in COVID-19 screening in Singapore remains conventional radiography, with CT scan used only as a problem-solving tool. The main reason we have continued to rely on conventional radiography as a screening tool lies in its ability to rapidly screen large numbers of patients accurately, without the prolonged downtime needed to clean the equipment and scanner room. Other important factors include the rapid availability of a radiology report and existing inventory of portable radiography machines. Radiography services are also ubiquitous in emergency departments and at the dedicated screening center at the National Centre for Infectious Disease.

The radiology departments within the larger and newer hospitals house imaging (MRI, CT, and US) and interventional radiology equipment, which are within negative pressure rooms. Adjoining anterooms have also been built to minimize air exchange with corridors, besides providing space for handwashing, donning and doffing of protective gowns, and storage of equipment.

Specific assets within the radiology facility have been assigned exclusively for suspected and confirmed cases of COVID-19. Clear boundaries are set for low traffic access routes and lift lobbies to be used. If a dedicated facility or equipment scanner cannot be assigned (eg, highly specialized equipment that is not duplicated, such as that used in nuclear imaging), isolation cases should be scanned at the end of the work day, not only to minimize cross-contamination but also to factor in time required for cleaning the room. Portable digital radiography equipment with wireless capabilities is useful, in that no additional handling of cassettes is required. The portable equipment is covered with single-use disposable plastic sheets and wiped down meticulously according to a set protocol for disinfection. Portable digital radiography and US units also allow for rapid “on-time” upload of images to the picture archiving and communication system for expedited reporting. Similarly, for CT and MRI scanners, standard cleaning is followed by terminal cleaning (sodium hypochlorite 1000 ppm, ultraviolet treatment for CT), which is usually performed by a specialized team.

Radiology Reporting

To support the screening efforts along with management of critically ill patients in the intensive care units, hospitals have a 1-hour turnaround time policy for chest radiograph reports. Such “high alert” studies are labeled for easy identification and are placed within a newly created worklist within the picture archiving and communication system. To meet this requirement for early reports, most departments have devoted additional staff resources to it. In the initial stages of the outbreak, senior radiologists (especially those with experience during SARS) were tasked with reporting these radiographs. Junior radiologists were able to tap into the expertise of these “SARS veterans” when they needed clarification and advice. Subsequently, with additional academic resources, such as journal references and teaching websites shared online, radiologists and residents alike have been able to familiarize themselves with typical diagnostic features and keep abreast of latest developments in case definitions and management of COVID-19. All staff were also made cognizant of the possibility of atypical presentations and to pay particular attention to incidental findings on imaging performed in patients not suspected of having COVID-19. A dedicated workflow to isolate and manage these patients with incidental suspicious findings is critical. More recently, guidance on CT reporting has also been made available by the Radiological Society of North America, endorsed by the Society of Thoracic Radiology and the American College of Radiology (18).

Communication

To stay current with the ever-changing landscape, staff may rely on regular detailed daily updates by the Ministry of Health, which provides a bird’s eye view of the situation and disseminates newly implemented policies (8). These updates are available online and are also comprehensively covered on traditional media channels. Communication channels between the hospitals’ outbreak management team and staff, as well as within the department, take the form of daily e-mail updates, regular recorded video messages, and officially approved instant messaging applications (19).

Sustaining the Effort

With the scale of this outbreak of pandemic proportions, the posture of a heightened state of vigilance must be maintained for some time. This, in addition to potential social isolation and disrupted work patterns, adds considerable stress to all health care workers. Therefore, there is a need for all to be aware of one’s own mental health to recognize a distressed colleague and to provide support where possible. Our hospitals’ senior management is aware of the importance of psychologic health, and avenues have been made available to staff should psychologic support be necessary. Interdepartmental mindfulness meditation sessions led by the senior management continue to be a well-received activity in one of the hospitals.

Through collaborating with coworkers from other departments, some have experienced greater camaraderie and are energized by the experience. Messages of support and encouragement, along with gift items from the public, help boost the morale of all health care workers as well.

Given the fluid situation on the ground during an outbreak, significant disruption will continue to happen. While we may not anticipate all possibilities, it is important to remain flexible yet responsive to new challenges. With time, existing protocols will need reinforcement for compliance. New protocols may occasionally need to be crafted and work processes be reviewed and refined along the way. Provision of health care to the uninfected patient population should as far as possible not be neglected, although compromises in the form of additional infection control measures and additional wait time can be unavoidable.

Most importantly, the outbreak will likely persist for a foreseeable period of time. It is therefore important to educate and manage staff expectations to new social norms, such as social distancing, heightened vigilance, and personal hygiene. It may also be timely to rethink and redesign workflows leveraging new technologies, such as video conferencing, text messaging, and mobile applications for scheduling, screening, and even clinical consultations, to minimize patient movement within the hospital. Lessons learned should also be incorporated into the design and planning of new radiology departments and facilities in the future.

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented challenge to the world. The radiology community in Singapore has fortunately been able to harness the lessons learned from SARS and the dress rehearsal from H1N1 infection to put in place a robust system supported by trained, experienced staff to manage, protect, detect, isolate, and sustain our efforts.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of all staff in the various radiology departments for their ideas, tireless effort, and dedication in combating the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a team effort.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: B.P.T. disclosed no relevant relationships. K.C.L. disclosed no relevant relationships. Y.G.G. disclosed no relevant relationships. S.S.X.K. disclosed no relevant relationships. S.Y.T. disclosed no relevant relationships. A.C.C.P. disclosed no relevant relationships. G.J.L.K. disclosed no relevant relationships. S.T.Q. disclosed no relevant relationships. S.B.S.W. disclosed no relevant relationships. L.P.C. disclosed no relevant relationships. B.S.T. disclosed no relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- COVID-19

- coronavirus 2019

- PPE

- personal protective equipment

- SARS

- severe acute respiratory syndrome

References

- 1.Gogna A, Tay KH, Tan BS. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: 11 years later--a radiology perspective. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014;203(4):746–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng LT, Chan LP, Tan BH, et al. Déjà Vu or Jamais Vu? How the severe acute respiratory syndrome experience influenced a Singapore radiology department’s response to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2020 Mar 4:1–5 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Health Facilities. Ministry of Health, Singapore Website. http://moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/singapore-health-facts/health-facilities. Published 2019. Accessed March 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. World Health Organization Website. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it. Accessed April 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.MOH Pandemic Readiness and Response Plan for Influenza and Other Acute Respiratory Diseases (Revised April 2014). Ministry of Health Singapore. https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/diseases-updates/interim-pandemic-plan-public-ver-_april-2014.pdf. Published April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lau TN, Teo N, Tay KH, et al. Is your interventional radiology service ready for SARS?: the Singapore experience. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2003;26(5):421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - March 11, 2020. World Health Organization Website. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Published March 11, 2020. Accessed March 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Updates On COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019) Local Situation. Ministry of Health, Singapore Website. https://www.moh.gov.sg/covid-19. Updated March 14, 2020. Accessed March 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) – Statistics and Research. Our World in Data Website. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus. Published 2020. Accessed April 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singapore’s strategy in fighting Covid-19. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/singapores-strategy-in-fighting-covid-19. Published March 25, 2020. Accessed April 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.MOH Circular No . 39/2020. Guidance on PPE use for healthcare workers during DORSCON orange. Ministry of Health Singapore. https://www.healthprofessionals.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider11/default-document-library/moh-cir-no-39_2020_7feb20_pte_dental_ppe-guidance.pdf. Published February 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Da Zhuang K, Tan BS, Tan BH, Too CW, Tay KH. Old threat, new enemy: is your interventional radiology service ready for the coronavirus disease 2019? Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2020 Feb 26 [Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Personal Data Protection Act Overview. Personal Data Protection Commission Singapore Website. https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/Overview-of-PDPA/The-Legislation/Personal-Data-Protection-Act. Updated August 7, 2018. Accessed March 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsou IY, Goh JS, Kaw GJ, Chee TS. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: management and reconfiguration of a radiology department in an infectious disease situation. Radiology 2003;229(1):21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang Y, Zhang H, Xie J, et al. Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology 2020 Feb 19:200432 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ACR Recommendations for the use of Chest Radiography and Computed Tomography (CT) for Suspected COVID-19 Infection. American College of Radiology. https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection. Published March 11, 2020. Updated March 22, 2020. Accessed April 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Society of Thoracic Radiology/American Society of Emergency Radiology COVID-19 Position Statement. Society of Thoracic Radiology. https://thoracicrad.org. Published March 11, 2020. Accessed April 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simpson S, Kay FU, Abbara S, et al. Radiological Society of North America Expert Consensus Statement on reporting chest CT findings related to COVID-19. Endorsed by the Society of Thoracic Radiology, the American College of Radiology, and RSNA. J Thorac Imaging 2020 Apr 21 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Legido-Quigley H, Asgari N, Teo YY, et al. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet 2020;395(10227):848–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]