SUMMARY

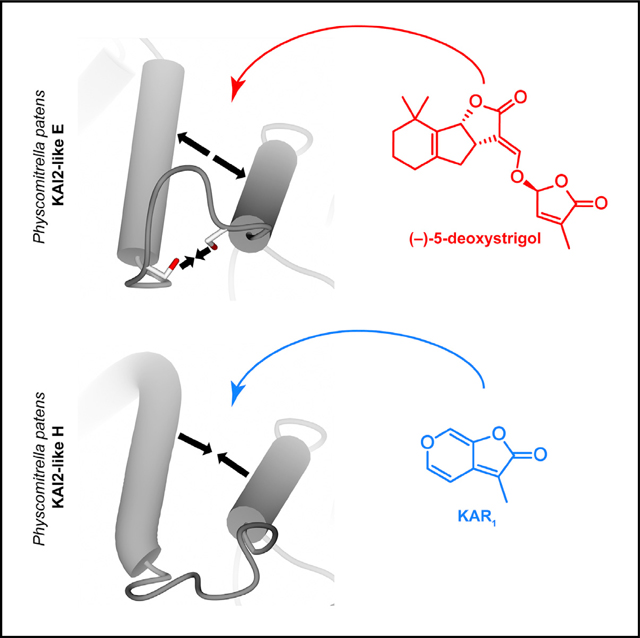

In plants, strigolactones are perceived by the dual receptor-hydrolase DWARF14 (D14). D14 belongs to the superfamily of α/β hydrolases and is structurally similar to the karrikin receptor KARRIKIN INSENSITIVE 2 (KAI2). The moss Physcomitrella patens is an ideal model system for studying this receptor family, because it includes 11 highly related family members with unknown ligand specificity. We present the crystal structures of three Physcomitrella D14/KAI2-like proteins and describe a loop-based mechanism that leads to a permanent widening of the hydrophobic substrate gorge. We have identified protein clades that specifically perceive the karrikin KAR1 and the non-natural strigolactone isomer (−)-5-deoxystrigol in a highly stereoselective manner.

In Brief

Bürger et al. dissect strigolactone and karrikin perception in the moss Physcomitrella patens, which first appeared on Earth 460 million years ago and provides an early evolutionary snapshot of 11 related receptor proteins. Three crystal structures reveal a loop-based mechanism that determines substrate specificity and affinity.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Strigolactones (SLs) are a class of plant hormones that were first discovered as (+)-strigol (Cook et al., 1966). Before that, SLs were identified as rhizosphere signals that induce seed germination of parasitic plants. However, it wasn’t until 2005 that it was demonstrated that SLs stimulated hyphal branching in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to trigger the symbiotic relationship with their host plants (Akiyama et al., 2005). Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis originated at least 460 million years ago and coincided with the appearance of bryophyte-like land plants (Remy et al., 1994). SLs were later found to be endogenous plant hormones that regulate shoot branching (Gomez-Roldan et al., 2008; Umehara et al., 2008), a key process in the formation of complex plant architecture. SL receptors with extraordinarily high (picomolar) affinity have been identified in Striga hermonthica (Conn et al., 2015; Toh et al., 2015; Tsuchiya et al., 2015).

Stereoselectivity is an important factor in SL synthesis and perception. The SL precursor carlactone is produced by the enzyme carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 8 (CCD8) (Alder et al., 2012; Seto et al., 2014). Carlactone is further processed into carlactonoic acid by MAX1, a cytochrome P450 protein (Abe et al., 2014). However, the genome of the moss Physcomitrella does not contain an obvious MAX1 ortholog (Delaux et al., 2012; Zimmer et al., 2013). SLs consist of a tricyclic ABC ring system connected to a butenolide D ring. Although the stereochemistry of the D ring appears to be conserved in the 2′R configuration within the naturally isolated SLs, two configurations of the junction between the B and the C ring result in the occurrence of two families of SLs: strigol types and orobanchol types (Xie et al., 2013).

In angiosperms, several studies have established the protein DWARF14 (D14) as the SL receptor (de Saint Germain et al., 2016; Nakamura et al., 2013; Yao et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2013). D14 belongs to the superfamily of α/β hydrolases, and in Arabidopsis thaliana, the D14 family comprises 3 members: the SL receptor D14, the karrikin receptor KARRIKIN INSENSITIVE 2 (KAI2), and D14 LIKE 2 (DLK2), a protein of un-known function. D14 and KAI2 both have a conserved catalytic triad comprising a serine, a histidine, and an aspartate. An intact catalytic triad is required for the biological function of both D14 (Hamiaux et al., 2012) and KAI2 (Sun and Ni, 2011; Waters et al., 2015a), and both proteins work in their signaling pathways through interaction with the F box protein MAX2 (Nelson et al., 2011). D14 and KAI2 display a highly similar overall fold and superimpose with a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of atomic positions of 1.05 Å over 262 residues. However, a major structural difference lies in their different substrate binding pocket architectures, with KAI2 having a smaller and narrower binding groove, ultimately determining the kind of ligand that can be bound by the receptor (Kagiyama et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2013). In Arabidopsis, functional separation between D14 and KAI2 has been demonstrated by promotor swaps and their inability to rescue the other protein’s mutant phenotype: D14 cannot complement the longer hypocotyl kai2 phenotype or restore responsiveness to karrikin, and KAI2 is unable to complement the d14 branching mutant (Waters et al., 2015b).

In the moss Physcomitrella patens, SLs are used to control colony expansion, a process that is partly similar to the quorum-sensing mechanism of bacterial growth regulation. Furthermore, the Physcomitrella SL synthesis mutant Ppccd8 can be complemented by exogenously adding the synthetic SL analog (±)-GR24 (Proust et al., 2011). The Physcomitrella patens genome encodes 11 functional D14- or KAI2-related proteins that can be divided into at least two clades. One of these clades shows closer homology to Arabidopsis thaliana KAI2 and contains PpKAI2-like B, C, D, and E. The other PpKAI2-like proteins seem to be more distinct from Arabidopsis KAI2 (Delaux et al., 2012). Homology modeling of PpKAI2-like protein structures has suggested that the previously mentioned cluster of PpKAI2-like B, C, D, and E is characterized by ligand binding pocket shapes and volumes that are close to Arabidopsis KAI2, accompanied by a group with similar ligand binding pockets containing PpKAI2-like H, I, and L. The same study predicted increased pocket volumes of PpKAI2-like F, K, and possibly G, suggesting these proteins as potential candidates for SL binding proteins. In addition, transcript-level analysis upon treatment with the synthetic SL analog (±)-GR24 identified PpKAI2-like C, F, G, H, J, K, and L as somehow involved in the SL signaling pathway (Lopez-Obando et al., 2016). However, experimental crystal structures of PpKAI2-like proteins are missing, and biochemical data about their ligand binding capabilities have not been published. In addition, it is uncertain whether the same stereoselectivity of SLs (Flematti et al., 2016) is given in biosynthesis (Alder et al., 2012; Seto et al., 2014) and perception (Scaffidi et al., 2014) as appears to be the case in higher plants. To obtain more insight into the evolution of SL and karrikin receptors, as well as to address the general question of how Physcomitrella perceives their respective ligands, we determined the crystal structures of three D14/KAI2-like proteins and characterized their binding to various ligands. In this study, we have discovered a loop-based structural mechanism that is required for high-affinity SL binding, and we have identified a protein clade that perceives the karrikin KAR1.

RESULTS

All Tested Physcomitrella KAI2-like Proteins Display Hydrolase Activity

We tested whether PpKAI2-like proteins are functional hydrolases. All proteins investigated (PpKAI2-like B, C, D, E, H, I, K, and L) displayed activity on the generic hydrolase substrate para-nitrophenyl (pNP) acetate. We determined catalytic efficiencies and found all of them either similar to or higher than AtKAI2 (Figure S1A), suggesting a possible dual receptor-hydrolase function similar to that of higher plants such as Arabidopsis and rice. D14 and DAD2 are known to be poor hydrolases, with a turnover rate of 1 (±)-GR24 molecule/3 min by the Arabidopsis protein (Zhao et al., 2013) and 3 (±)-GR24 molecules/hr by the Petunia paralog, DAD2 (Hamiaux et al., 2012). The reason for this might be product inhibition, and a single-turnover model for D14 proteins has been proposed using fluorescent probes and the Pisum sativum D14 homolog RMS3 (de Saint Germain et al., 2016). However, it is unclear whether this holds true for real SLs and other substrates. Using pNP acetate as a substrate, we detected a poor turnover rate of Arabidopsis D14 as well, whereas the Physcomitrella patens orthologs had higher activities (Figure S1A).

Crystal Structures of Physcomitrella patens KAI2-like Proteins C, E, and H

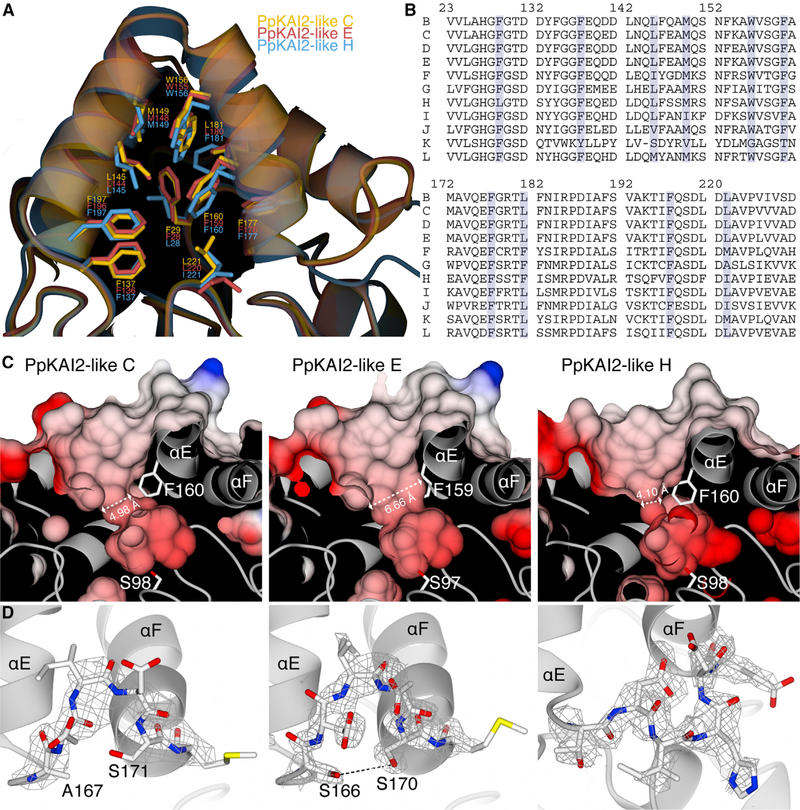

We solved the crystal structures of Physcomitrella patens KAI2-like proteins C, E, and H at resolutions of 2.7, 1.9, and 2.0 Å, respectively. As expected, they all fold into a canonical α/β hydrolase architecture. The closest structures in the PDB, according to a Dali search (Holm and Rosenström, 2010), were Arabidopsis thaliana KAI2 (PDB: 4HRY) for PpKAI2-like C and E, with RMSDs of 0.6 and 0.7 Å over 268 residues, and the Pertunia hybrida SL receptor DAD2 (PDB: 4DNP) for PpKAI2-like H, with an RMSD of 1.0 Å over 263 residues. We found major structural differences in the arrangements and volumes of the hydrophobic substrate binding sites; in particular, we observed different diameters of the hydrophobic pockets: PpKAI2-like E had the widest of the analyzed pockets (6.66 Å), followed by PpKAI2-like C (4.98 Å), and PpKAI2-like H, which had a substrate binding pocket diameter of 4.10 Å (Figure 1C). Overall volumes of the pockets were 352 Å3 for PpKAI2-like C, 370 Å3 for PpKAI2-like E, and 327 Å3 for PpKAI2-like H (Figure S1B). The smaller volume of PpKAI2-like H is in agreement with previous homology modeling, whereas the difference between PpKAI2-like C and PpKAI2-like E is not (Lopez-Obando et al., 2016). We did not observe significant variation in the residues forming the cavity walls that would influence the diameter of the tunnel. Residues L28 and F181 in PpKAI2-like H differ from those in PpKAI2-like C and E; however, they are distant from the narrowest part of the binding groove (Figures 1A and 1B).

Figure 1. Different PpKAI2-like Proteins Feature Different Ligand Binding Site Architectures.

(A) Superimposition of PpKAI2-like C, E, and H showing the residues involved in the formation of the hydrophobic substrate tunnel.

(B) Multiple/sequence alignment of PpKAI2-like proteins highlighting the amino acids shown in (A).

(C) Clipped surface view of different PpKAI2-like proteins showing their tunnel diameters.

(D) Interaction between helices αE and αF. FO-FC omit maps for the loops are shown as gray wire.

A more detailed analysis showed that the diameter of the binding pocket seemed to be controlled by the interaction between helix αE, which constitutes the wall of the hydrophobic cavity, and helix αF. Helices αE and αF are connected by a loop segment that appeared to determine the degree of freedom that is available for helix αE to allow it to move into the rest of the binding site. Although a hydrogen bond between Ser166 in helix αE and Ser170 in helix αF seemed to limit the movement of these helices in PpKAI2-like E, the hydrogen bond is missing from PpKAI2-like C due to a serine-to-alanine substitution in helix αE. In PpKAI2-like H, the loop has a different conformation, leading away from the helices and apparently not establishing a direct force between αE and αF (Figure 1D). We postulated that manipulation of this interaction could modify SL binding affinities due to an altered hydrophobic binding site.

The Interaction between Helices αE and αF Determines Ligand Affinity

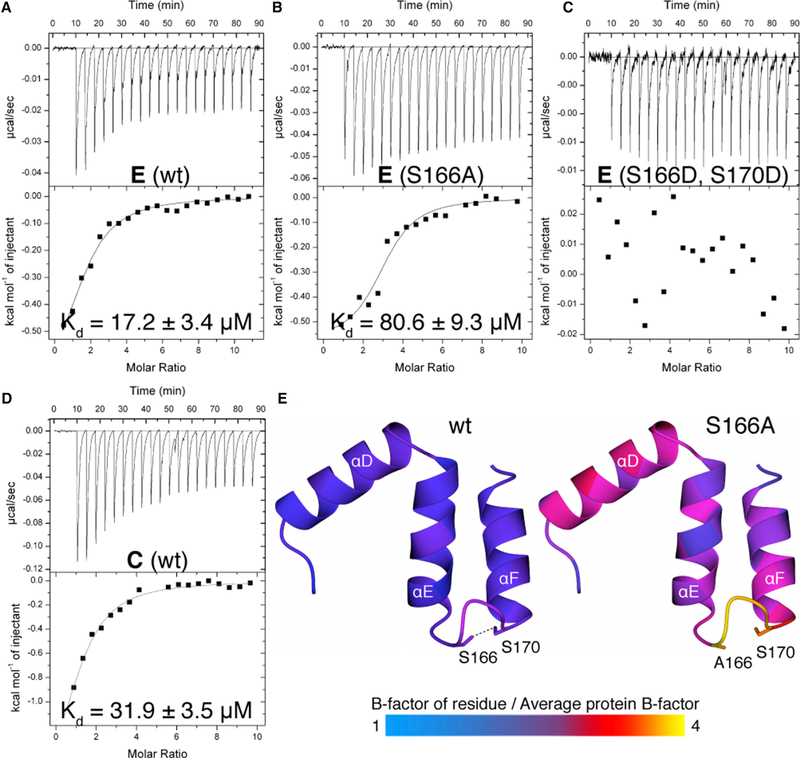

Because of the high protein yields upon overexpression in E. coli and because of the higher resolution of the X-ray dataset compared to the other protein structures obtained in this study (Table S1), we used PpKAI2-like E for subsequent experiments to investigate the importance of the loop that connects helices αE and αF. We determined the affinity between PpKAI2-like E and synthetic SL analog (±)-GR24 using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and found a dissociation constant of 17 μM (Figure 2A). We then created two variants of the protein, one in which we replaced Ser166 with an alanine and one in which we substituted both serines with aspartic acids, replacing the hydrogen bond with a repulsive force of charges. We determined the dissociation constants of these proteins to (±)-GR24. We found a Kd of 81 μM with PpKAI2-like E S166A, and we were unable to detect binding of (±)-GR24 by PpKAI2-like E S166D S170D (Figures 2B and 2C). We tested all variants for hydrolase activity using the substrate pNP acetate. We saw almost identical enzyme activities and concluded that the different affinities are caused not by misfolding of the mutant proteins but by manipulation of the tunnel architecture (Figure S2A). In addition, we observed a lower affinity of (±)-GR24 to PpKAI2-like C wild-type compared to PpKAI2-like E wild-type (32 μM compared to 17 μM, respectively) (Figures 2A and 2D). Enzymatic reactions subjected to ITC experiments often display a stepwise shift of the baseline due to the additional heat being either produced or taken up by the catalysis of the substrate after each injection (Andújar-Sánchez et al., 2006; Hansen et al., 2016). While we observed a shift in the baseline, this shift also occurred in PpKAI2-like E S166D S170D, which does not bind (±)-GR24. Furthermore, no such shift was visible in the ITC diagram of PpKAI2-like C binding to (±)-GR24 (Figure S2B). Therefore, we have chosen to apply a one-site binding model for curve fitting, which obtained the previously mentioned dissociation constants.

Figure 2. Manipulation of the Loop-Based Interaction between Helices αE and αF Weakens and Abolishes (±)-GR24 Binding.

(A–C) Isothermal titration calorimetry of (±)-GR24 with PpKAI2-like E wild-type (A) and mutant versions S166A (B) and S166D S170D (C).

(D) Isothermal titration calorimetry of (±)-GR24 with PpKAI2-like C.

(E) Comparison of flexibility of structural segments contributing to the lid structure of PpKAI2, colored according to atomic B factors.

To obtain more details about the structural organization of the ligand binding site, we solved the crystal structure of PpKAI2-like E S166A. We found significantly elevated temperature factors (B factors) of the loop connecting helices αE and αF and of helices αD-F themselves when compared to PpKAI2-like E wild-type (Figure 2E). We conclude that the loss of the hydrogen bond between helices αE and αF resulted in higher mobility of the tunnel-forming lid helices and that the rigidity given by this bond is a prerequisite for ligand binding at a higher affinity.

PpKAI2-like C, D, and E Are Highly Stereoselective for (−)-5-Deoxystrigol

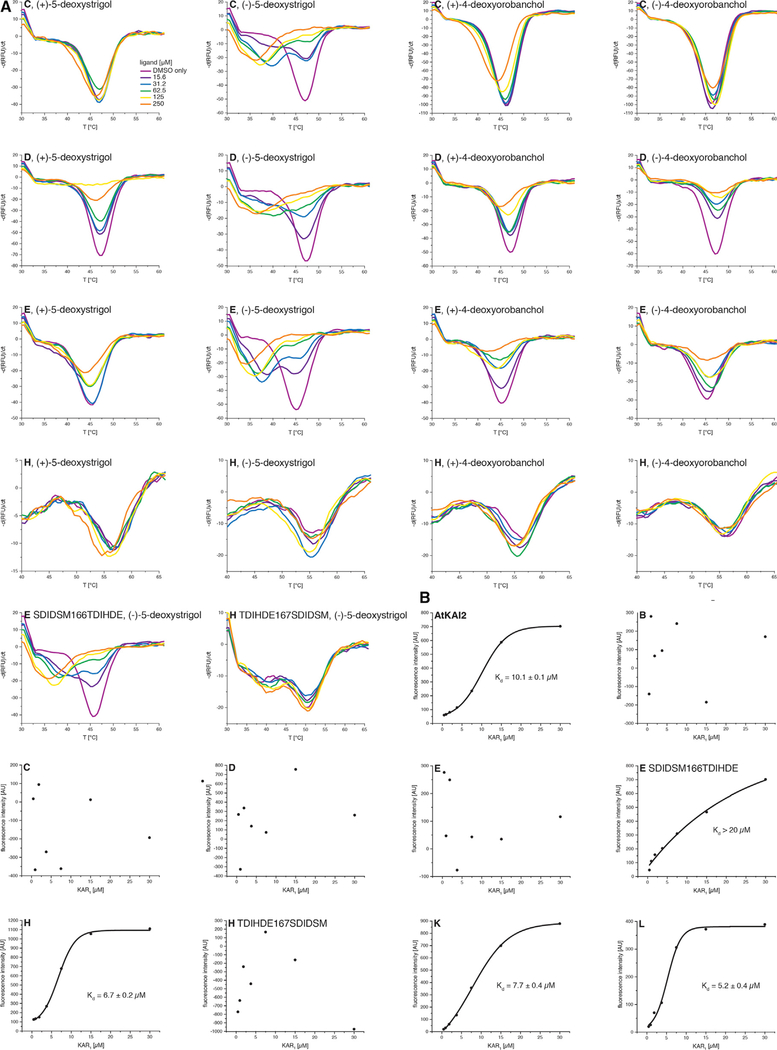

We screened potential interaction of (±)-GR24 with PpKAI2-like proteins B, C, D, E, H, K, and L using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF). We were unable to produce sufficient protein amounts of PpKAI2-like F, G, I, and J. Upon incubation with (±)-GR24, we detected destabilization of PpKAI2-like C, D, and E, the latter of which displayed the strongest shift of the protein melting point (Figure S3A). We then used enantiomeric (+)-5-deoxystrigol and (−)-5-deoxystrigol, as well as enantiomeric (+)-4-deoxyorobanchol and (−)-4-deoxyorobanchol to probe for possible stereoselectivity and SL type preference of the receptor proteins. We found absolute preference of PpKAI2-like C, D, and E for (−)-5-deoxystrigol and were unable to detect a change in melting points when the other SL isomers were used (Figure 3A). We docked (−)-5-deoxystrigol into the crystal structure of PpKAI2-like E and found that the molecule would fit into the hydrophobic binding site of the protein, whereas docking of (+)-5-deoxystrigol resulted in the ligand not being fully inserted into the binding pocket (Figure S3B). No reliable molecular docking result could be obtained for either of the two 4-deoxyorobanchol enantiomers. To directly test for hydrolysis of 5-deoxystrigol, we monitored degradation of (−)-5-deoxystrigol and (+)-5-deoxystrigol upon interaction with PpKAI2-like C, D, and E using triple-stage quadrupole mass spectrometry. We recorded loss of intact (−)-5-deoxystrigol mass when incubated with the proteins but did not observe any effect on (+)-5-deoxystrigol (Figure S3C). We further found the 96 Da mass of the D ring to be attached to the active site histidines of PpKAI2-like C, D, and E when incubated with (−)-5-deoxystrigol. This modification has been previously reported for the Pisum sativum SL receptor RMS3 (de Saint Germain et al., 2016). We were unable to detect the modification upon incubation of the proteins with (+)-5-deoxystrigol (Figure S3D). Altogether, these results provide evidence that PpKAI2-like C, D, and E stereoselectively bind and hydrolyze (−)-5-deoxystrigol.

Figure 3. PpKAI2-like C, D, and E Are Highly Stereoselective for (−)-5-deoxystrigol, and PpKAI2-like H, K, and L Bind the Karrikin KAR1.

(A) Differential scanning fluorimetry with 4 stereoisomers of strigolactones and PpKAI2-like proteins.

2(B) Microdialysis assay to analyze KAR1 binding by different PpKAI2-like proteins.

Pp-KAI2-like H, K, and L Bind the Karrikin KAR1

A previous study has provided genetic evidence that AtKAI2 mediates responses to the unnatural SL stereoisomer (−)-5-deoxystrigol (Scaffidi et al., 2014). We screened all proteins in this study for possible binding of the karrikin KAR1 using an established fluorescence-based microdialysis assay (Guo et al., 213). We detected KAR1 binding by PpKAI2-like K, L, and H (Figure 3B). We concluded that a shallower binding site is, at least in the case of PpKAI2-like H, selective for binding of karri-kin, but not of SLs. We determined dissociation constants of KAR1 to the Physcomitrella proteins and found Kd values of 6.7 μM for PpKAI2-like H, 7.7 μM for PpKAI2-like K, and 5.2 μM for PpKAI2-like L, values that are similar to the published affinity of KAR1 to AtKAI2, which is 9 μM (Guo et al., 2013). We were unable to detect KAR1 binding by PpKAI2-like C, D, and E, suggesting that binding of (−)-5-deoxystrigol by these proteins happens exclusively and does not coexist with karrikin perception.

We further created protein versions in which we switched the loops between PpKAI2-like E and PpKAI2-like H (PpKAI2-like E SDIDSM166TDIHDE and PpKAI2-like H TDIHDE167SDIDSM, respectively). While PpKAI2-like E SDIDSM166TDIHDE showed weak binding to KAR1 compared to no binding detected for PpKAI2-like E wild-type (Figure 3B), its affinity to both (−)-5-deoxystrigol and (±)-GR24 was reduced compared to wild-type (Figures 3A and S3A). PpKAI2-like H TDIHDE167SDIDSM lost KAR1 binding ability (Figure 3B) but displayed weak affinity to both (−)-5-deoxystrigol and (±)-GR24 (Figures 3A and S3A), compared to no binding observed for PpKAI2-like H wild-type.

PpKAI2-like C, D, E, and H Do Not Bind rac-Carlactone

The Physcomitrella enzyme PpCCD8 has been identified as carlactone synthase, and Ppccd8Δ mutant lines displayed enhanced caulonema growth, which can be reverted by exogenous treatment with GR24 or carlactone (Decker et al., 2017). In addition, a reassessment of previously obtained results using newer mass spectrometry instrumentation could not confirm the presence of canonical SLs but did report the detection of carlactone (Yoneyama et al., 2018). This has pushed forward the concept of carlactone being an actual signaling component in Physcomitrella, rather than a precursor molecule. We have, therefore, examined potential binding of rac-carlactone by PpKAI2-like C, D, E, and H but were unable to detect any interaction using DSF (Figure S3A).

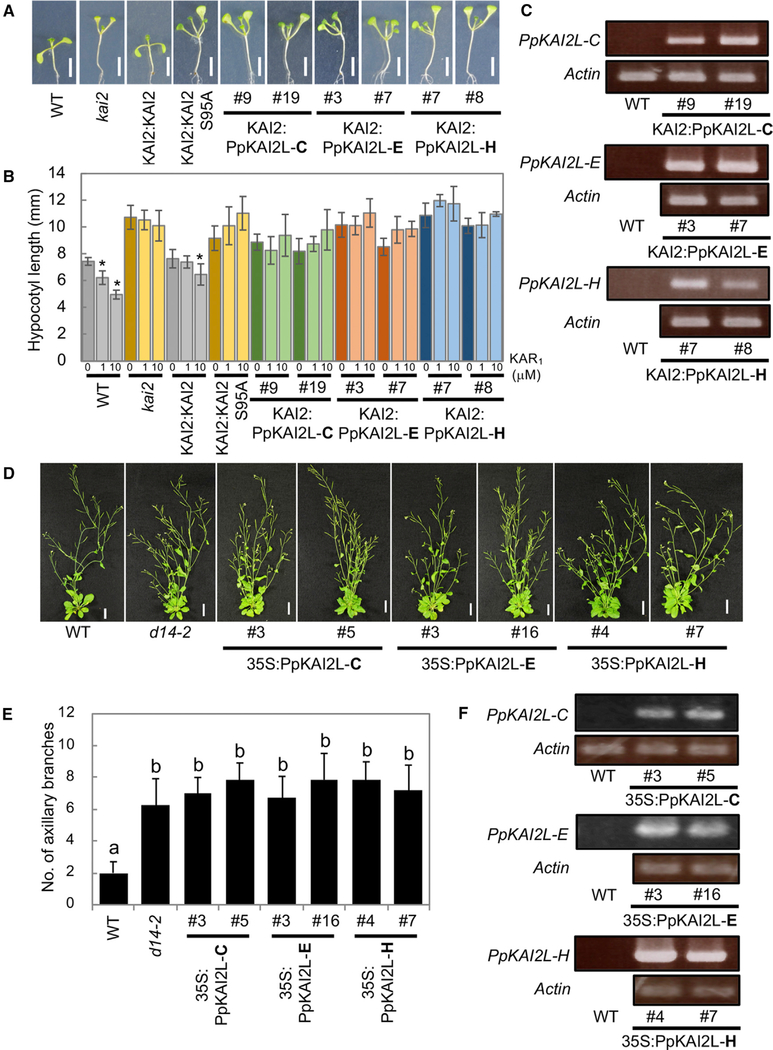

Tested PpKAI2-like Proteins Are Unable to Complement the Arabidopsis kai2 or d14 Mutants

We analyzed all PpKAI2-like proteins for their capability to complement the Arabidopsis kai2 mutant, which has a long hypocotyl phenotype (Sun and Ni, 2011). We found that none of the PpKAI2-like proteins were able to complement the kai2 mutant phenotype. Because the intrinsic signaling molecule for KAI2 is unknown, we tested Arabidopsis kai2 overexpressing PpKAI2-like proteins for potential response to exogenously provided karrikin KAR1. However, no response of any of the lines was observed (Figures 4A–4C and S4A–S4C).

Figure 4. Complementation Studies of Arabidopsis kai2 and d14 Mutant Lines Using PpKAI2L Genes.

(A and B) Hypocotyl growth phenotypes (A) and KAR1 responses (B) of Arabidopsis kai2 complemented with PpKAI2-like-C, E, and H. Wild-type KAI2 and KAI2 S95A were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Seedlings were grown on agar plates containing DMSO (representative phenotypes are shown in A) and 1 and 10 μM KAR1 under short-day conditions for 9 days. Scale bars represent 5 mm. Data are means ± SD (n = 7–9). Means with asterisks indicate significant inhibitions from mock-treated seedlings in each line (Tukey-Kramer, p < 0.05).

(C) Gene expression analysis of PpKAI2-like C, E, and H in the transgenic lines used in (A) and (B) by semi-qRT-PCR. Actin was used as an internal control.

(D and E) Shoot-branching phenotypes (D) of Arabidopsis d14 complemented with PpKAI2-like C, E, and H. Plants were grown for 45 days. The number of axillary branches (>5 mm) per plant is shown (E) as means ± SD (n = 13–14). Means with different letters indicate significant differences (Steel-Dwass, p < 0.05).

(F) Gene expression analysis of PpKAI2-like C, E, and H in the transgenic lines used in (D) and (E) by semi-qRT-PCR.

To further identity similarities and differences in SL signaling between bryophytes and higher plants, we attempted complementation of the Arabidopsis thaliana d14 (atd14) mutant, which has a hyper-branching phenotype (Chevalier et al., 2014). However, none of the Physcomitrella genes were able to complement the atd14 phenotype (Figures 4D–4F, S4D, and S4E).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have identified a specific clade of Physcomitrella D14 proteins that perceive the non-natural SL (−)-5-deoxystrigol in a highly stereoselective manner. The synthesis of (−)-5-deoxystrigol has not been reported in Physcomitrella or higher plants thus far, and it is thought that if plants produce SLs with a 2′S configuration of the D ring, they must do so at rather low concentrations (Akiyama and Hayashi, 2006; Yo-neyama et al., 2018). The high stereospecificity of the SL precursor carlactone-producing enzyme CCD8 is believed to be responsible for the stereochemistry of all carlactone-derived SLs (Alder et al., 2012; Seto et al., 2014). Physcomitrella lacks an obvious homolog of MAX1 (Delaux et al., 2012; Zimmer et al., 2013), the protein catalyzing the oxidation of carlactone into carlactonoic acid. Therefore, the natural SL molecules in Physcomitrella are likely unknown. In addition, complete separation of the roles of D14 and KAI2 in regard to their ligand perception has not been established. Responses to non-natural (−)-5-deoxystrigol and (−)-GR24 through the karrikin receptors KAI2 of Arabidopsis and rice have been previously reported. However, this signaling occurred at very high ligand concentrations, and it was shown that the SL receptor D14 responds to both stereoisomers of GR24 (Scaffidi et al., 2014). We have excluded the possibility of KAR1 binding to the PpKAI2-like proteins C, D, and E and could not detect binding of any other SLs used (Figure S1C). We found a modification representing the D ring covalently attached to the active site histidines of PpKAI2-like C, D, and E, which suggests that the hydrolysis mechanism is likely similar or identical to what has previously been described for the Pisum sativum D14 homolog RMS3 (de Saint Germain et al., 2016).

2PpKAI2-like B, C, D, and E cluster in one clade most closely to the karrikin receptor KAI2 from Arabidopsis thaliana (Delaux et al., 2012), and homology modeling has suggested that they are functionally related to Arabidopsis KAI2 due to similar ligand binding pocket volumes (Lopez-Obando et al., 2016). However, while our experimental structural structures show that PpKAI2-like C and E display pocket shapes that are similar to each other, both proteins bind (±)-GR24, and PpKAI2-like B, C, D, and E do not bind KAR1. Lopez-Obando et al. (2016) have also suggested that PpKAI2-like H and L might feature relatively small ligand pocket volumes, a result that is in agreement with our crystal structure of PpKAI2-like H and seems plausible considering our findings about KAR1 binding by PpKAI2-like H and L. How-ever, we also found that PpKAI2-like K binds KAR1, which might cast doubt on the suggestion that this protein is a receptor for SLs. A future crystal structural of PpKAI2-like K will hopefully be able to clarify this discrepancy.

Although the natural occurrence of (−)-5-deoxystrigol has not been reported to date, we believe that it would be implausible for an organism to maintain 3 receptor proteins with high specificity for a ligand that does not exist in nature. Because the enzyme CCD8 appears to be highly stereospecific, one might speculate about an alternative route for SL biosynthesis, possibly synthesizing SLs with a different stereochemistry. A previous study has claimed the identification of SLs in Physcomitrella (Proust et al., 2011), a result that, unfortunately, could not be reproduced in another study (Decker et al., 2017) or when using newer mass spectrometry equipment (Yoneyama et al., 2018). Therefore, the actual signaling molecules in Physcomitrella have likely not yet been identified. Thus, it appears that either 2′S-configured SLs are being produced or that (−)-5-deoxystrigol is a working mimic of one or several of the actual signaling molecules, which ought to be chemically close to the non-natural SL isomers. This includes the possibility of (−)-5-deoxystrigol mimicking one or several unknown endogenous KAI2 ligands, the existence of which has seen growing acceptance in the field (Conn and Nelson, 2016; Flematti et al., 2013; Morffy et al., 2016).

We have identified a loop that regulates the rigidity of the hydrophobic ligand binding pocket. This implies that a preformed architecture is required for efficient SL perception and that the diameter of the binding pocket is controlled by a structural segment, the design of which determines the affinity of the receptor to the ligand. In D14 proteins of higher plants, the connection between helices αE and αF is kept rather rigid too. In Arabidopsis and Oryza D14, the loop is shorter and is anchored into helix αF with a rigid proline. In contrast, KAI2 has a glycine substitution for the first serine, introducing more flexibility into the mechanism. Both the proline at the end of the loop in D14 proteins and the second glycine at the beginning of the loop in KAI2 proteins are conserved (Figure S1D). In addition, the amino acids forming the loop segment that connects helices αE and αF are not conserved in the D14/KAI2 protein family as a whole. Rather, they are conserved separately within the Eu-KAI2 and Eu-D14 groups (Bythell-Douglas et al., 2017). Therefore, the residues forming the loop segment seem to play an essential role in formation of the ligand binding pocket shape, and a certain rigidity of the binding pocket appears to be an important part of SL perception. This concept is likely to have evolved independently in mosses and vascular plants. The results from our structural studies and isothermal titration colorimetry are corroborated by the data obtained from DSF, which showed a stronger shift of the protein melting point for both (±)-GR24 and (−)-5-deoxystrigol to PpKAI2-like E compared to PpKAI2-like C and D. An analogous study using KAI2 (HTL) and D14 proteins from the parasitic weed Striga hermonthica concluded that ligand specificity in Striga is mostly regulated by the arrangement of the first helix in the protein lid. Further-more, a subgroup highly sensitive for SL binding has developed and features a tyrosine-to-phenylalanine substitution, resulting in the loss of a hydrogen bond between the first and the third lid helices and leading to an increased ligand binding pocket size (Xu et al., 2018). However, this residue is rather uninformative when applied to the substrate specificity of the Physcomitrella homologs, because they all have a phenylalanine at that position.

This study suggests the presence of receptors for karrikin, a smoke-derived molecule, in Physcomitrella, although to our knowledge, a biological function of karrikin in moss has not been reported and a previous study has not found any effect of KAR1 on Physcomitrella caulonema growth (Hoffmann et al., 2014). We have identified three PpKAI2-like proteins that bind the karrikin KAR1 in vitro, but none of the tested PpKAI2-like proteins were able to complement the Arabidopsis kai2 mutant phenotype in planta. This might be due to incompatibilities in downstream signaling between Physcomitrella and Arabidopsis, for instance, that PpKAI2-like proteins are unable to form a functional signaling complex with Arabidopsis MAX2 or SMAX1 after ligand binding. Ligand binding pockets within the D14/KAI2 protein family have most likely evolved independently in vascular plants and mosses (Bythell-Douglas et al., 2017). Therefore, binding of KAI2 by Arabidopsis MAX2 might require protein features that are present on the surface of PpKAI2-like H but are not on PpKAI2-like K and L, although they are able to bind the ligand KAR1 at similar affinities in vitro. Future studies will also have to clarify whether the ligand binding pockets in PpKAI2-like K and L are comparable to the one in PpKAI2-like H.

In a similar study that assessed the function of KAI2-like proteins in the lycophyte Selaginella moellendorffii and in the liver-wort Marchantia polymorpha, homologs from these two species were able to hydrolyze (±)-GR24 in vitro but failed to complement the Arabidopsis d14 or kai2 mutants. However, one Selaginella KAI2-like protein rescued the seedling and leaf development phenotypes of the Arabidopsis kai2 mutant (Waters et al., 2015b). In this context, another study has shown that SL signaling in Physcomitrella patens does not require the PpMAX2 protein and that the Arabidopsis max2 mutant cannot be complemented with the Physcomitrella homolog (Lopez-Obando et al., 2018).

We expect our work to lay the structural foundation for up-coming research progressing toward the identification of the native Physcomitrella SL chemistry.

STAR★METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Joanne Chory (chory@salk.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Escherichia coli

For DNA extraction, E. coli DH5α was used. For protein expression, E. coli BL21 (DE3) Codon plus RIL was used. DH5α was grown in Lysogenic Broth (LB) medium at 37°C and BL21 were grown in Terrific Broth (TB) medium at 23°C before and at 18°C after protein induction.

Arabidopsis thaliana

The model plant used in this study was Arabidopsis thaliana. The wild-type used is the accession Columbia (Col-0). The various mutants and overexpression lines have been described in the Key Resources Table. Plants were grown at 22°C under a 16/8 h light/dark photoperiod or under continuous white light.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | NEB | C2989K |

| E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL | Agilent Technologies | 230245 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| BP clonase | ThermoFisher | 11789021 |

| LR clonase | ThermoFisher | 11791043 |

| Glutathione Sepharose FF | GE Healthcare | 17513201 |

| HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg | GE Healthcare | 28–9893-33 |

| HRV3 protease | Sigma-Aldrich | SΑE0045 |

| KAR1 | OlChemIm s.r.o. | 025 7391 |

| Chiralix | CX27716 | |

| rac-GR24 | OlChemIm s.r.o. | 025 6721 |

| rac-carlactone | N/A | |

| (+)-5-deoxystrigol | OlChemIm s.r.o. | 025 7121 |

| (−)-5-deoxystrigol | OlChemIm s.r.o. | 025 7131 |

| (+)-4-deoxyorobanchol | OlChemIm s.r.o. | 025 7141 |

| (−)-4-deoxyorobanchol | OlChemIm s.r.o. | 025 7151 |

| Sypro Orange 5,000X | ThermoFisher | S6650 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| PpKAI2-like C | This paper | PDB: 6ATX |

| PpKAI2-like E | This paper | PDB: 6AZB |

| PpKAI2-like E S166A | This paper | PDB: 6AZC |

| PpKAI2-like H | This paper | PDB: 6AZD |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| KAI2:PpKAI2L-C/kai2 | This paper | N/A |

| KAI2:PpKAI2L-E/kai2 | This paper | N/A |

| KAI2:PpKAI2L-H/kai2 | This paper | N/A |

| KAI2:PpKAI2L-B/kai2 | This paper | N/A |

| KAI2:PpKAI2L-D/kai2 | This paper | N/A |

| KAI2:PpKAI2L-K/kai2 | This paper | N/A |

| KAI2:PpKAI2L-L/kai2 | This paper | N/A |

| KAI2:AtKAI2/kai2 | This paper | N/A |

| KAI2:AtKAI2SA/kai2 | This paper | N/A |

| 35S:PpKAI2L-C/atd14 | This paper | N/A |

| 35S:PpKAI2L-E/atd14 | This paper | N/A |

| 35S:PpKAI2L-H/atd14 | This paper | N/A |

| 35S:PpKAI2L-B/atd14 | This paper | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| All oligonucleotides are listed in Table S2. | N/A | |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pGEX-GST-PpKAI2L-B | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-PpKAI2L-C | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-PpKAI2L-D | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-PpKAI2L-E | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-PpKAI2L-E S166A | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-PpKAI2L-E S166D S170D | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-PpKAI2L-E SDISDM166TDIHDE | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-PpKAI2L-E S97A | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-PpKAI2L-H | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-PpKAI2L-H TDIHDE167SDIDSM | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-PpKAI2L-H S98A | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-PpKAI2L-K | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-PpKAI2L-L | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-AtD14 | This paper | N/A |

| pGEX-GST-AtKAI2 | This paper | N/A |

| pENTR-PpKAI2L-C | This paper | N/A |

| pENTR-PpKAI2L-E | This paper | N/A |

| pENTR-PpKAI2L-H | This paper | N/A |

| pENTR-PpKAI2L-B | This paper | N/A |

| pENTR-PpKAI2L-D | This paper | N/A |

| pENTR-PpKAI2L-K | This paper | N/A |

| pENTR-PpKAI2L-L | This paper | N/A |

| pGWB1-KAI2Pro | This paper | N/A |

| pGWB1-KAI2Pro:PpKAI2L-C | This paper | N/A |

| pGWB1-KAI2Pro:PpKAI2L-E | This paper | N/A |

| pGWB1-KAI2Pro:PpKAI2L-H | This paper | N/A |

| pGWB1-KAI2Pro:PpKAI2L-B | This paper | N/A |

| pGWB1-KAI2Pro:PpKAI2L-D | This paper | N/A |

| pGWB1-KAI2Pro:PpKAI2L-K | This paper | N/A |

| pGWB1-KAI2Pro:PpKAI2L-L | This paper | N/A |

| pGWB2-PpKAI2L-C | This paper | N/A |

| pGWB2-PpKAI2L-E | This paper | N/A |

| pGWB2-PpKAI2L-H | This paper | N/A |

| pGWB2-PpKAI2L-B | This paper | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| XDS | Kabsch, 2010 | http://xds.mpimf-heidelberg.mpg.de |

| Phenix | Adams et al., 2010 | https://www.phenix-online.org |

| Coot | Emsley et al., 2010 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot |

| CCP4mg | McNicholas et al., 2011 | http://www.ccp4.ac.uk/MG |

| ProteinsPlus | Fährrolfes et al., 2017 | https://proteins.plus |

| Origin | Originlab | https://www.originlab.com |

| XLfit | IDBS | https://www.idbs.com/excelcurvefitting |

| PRODRG | Schuttelkopf and van Aalten, 2004 | http://davapc1.bioch.dundee.ac.uk/cgi-bin/prodrg |

| AutoDock Vina | Trott and Olson, 2010 | http://vina.scripps.edu |

| Fiji | Schindelin et al., 2012 | https://fiji.sc |

| SPSS Statistics 22.0 | IBM | https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics |

| RawConverter | He et al., 2015 | http://fields.scripps.edu/rawconv/ |

| ProLuCID | Xu et al., 2015 | https://omictools.com/prolucid-tool |

| DTASelect | Tabb et al., 2002 | https://omictools.com/dtaselect-tool |

| Skyline | MacLean et al., 2010 | https://sciex.com/products/software/skyline-software |

METHOD DETAILS

Molecular cloning

Genes were cloned into a Gateway-compatible pGEX 4T3 expression vector with a HRV3 protease recognition site immediately up-stream to the start codon, leaving two amino acid residues Gly-Pro as cloning artifact. We used published coding sequences for this study (Lopez-Obando et al., 2016). Genes were either cloned from Physcomitrella patens cDNA libraries or were synthesized.

Protein purification

Heterologous expression was carried out in BL21-CodonPlus-RIL cells (Agilent), grown at 23°C until an OD600 = 0.6, and induced for 16–18 h at 18°C using 0.1 mM IPTG. GST fusion proteins were loaded onto a glutathione Sepharose column in 50 mM TRIS-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5% Glycerol, 1 mM TCEP-HCl, final pH 7.7. The column was washed until no protein flow-through could be found by UV detection, and HRV3 protease was added on the column overnight. The cleaved target protein was then eluted using the above buffer, and further purified to homogeneity by size exclusion chromatography using a GE Healthcare HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 column in 20 mM TRIS-HCl, 30 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP-HCl, final pH 7.7. Proteins were concentrated to at least 15–20 mg/ml and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Protein crystallization and structure solution

Protein crystals were grown under the following conditions in 1 or 2 μl hanging drops using a 1:1 protein:reservoir ratio. PpKAI2-like C: 1.2 M ammonium sulfate, 0.2 M Bis-Tris pH 6.5. 1.3 M sodium malonate was used as cryo-protectant. PpKAI2-like E: 0.1 M Tris pH 8.5, 10% PEG 20,000. 30% glycerol was used as cryo-protectant. PpKAI2-like E S166A: 0.1 M Tris pH 8.5, 30% PEG 8,000. 25% glycerol was used as cryo-protectant. PpKAI2-like H: 1.8 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M MES 6.5, 5% PEG 400. 1.3 M sodium malonate was used as cryo-protectant. X-ray data were collected at the Advanced Light Source at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory at beamline 821 and processed with XDS (Kabsch, 2010). All structures were solved by molecular replacement with PHASER (McCoy et al., 2007) using a single chain of Arabidopsis thaliana KAI2 (PDB code 4IH1) as template. Five percent of the data were flagged for R-free and initial models were build using AutoBuild (Terwilliger et al., 2008) as part of PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010), manually corrected and finalized with Coot (Emsley et al., 2010), refined with phenix.refine (Afonine et al., 2012), and validated with MolProbity (Chen et al., 2010). All structures were visualized with CCP4mg (McNicholas et al., 2011). Substrate binding pocket volumes in PpKAI2-like C, E and H were measured and visualized with DoGSiteScorer as part of the ProteinsPlus web server (Fährrolfes et al., 2017).

DSF

DSF experiments were performed in a CFX384 system (Biorad). Sypro Orange (Life Technologies) was used as reporter. 10 μl protein was heat-denatured using a linear 25°C to 95°C gradient at a rate of 1°C per minute. The denaturation curve and its derivative were obtained using the CFX manager software. Final reaction mixtures were prepared in 20 μl volumes in triplicates in 384 well white microplates. Reactions were carried out in 20 mM TRIS-HCl, 30 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP-HCl, final pH 7.7. A final 3x concentration of Sypro Orange was used.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Isothermal titration calorimetry experiments were performed in a MicroCal ITC200 MicroCalorimeter. Protein solutions at a concentration of 1800 μM were titrated into a 40 μM (±)-GR24 solution in 20 steps of 2 μl and in 240 s intervals. Thermodynamic parameters were then calculated using the MicroCal ITC software as part of Origin (Originlab).

Kinetic analysis

Parameters of steady state kinetics were measured using the colorimetric compound pNP acetate and the release of yellow p-nitro-phenol was monitored by recording the absorbance at 410 nm at room temperature over 15 min in 60 s intervals using a Tecan Safire II microplate reader. Reactions were measured as triplicates in 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.52–7.55, 0.01% (v/v) Triton X-100. Enzyme concentrations in the assay were 100 nM. The resulting absorbance was referenced to a linear pNP absorbance-concentration relationship and Michelis Menten parameters were determined with IDBS XLfit.

Equilibrium microdialysis

KAR1 fluorescence intensity detection to determine affinities to receptor proteins was used as previously described (Guo et al., 2013). Measurements were conducted in triplicates and Kd values were determined applying a non-linear dose response fit using Origin (OriginLab).

Ligand docking

Files for molecular docking of (–)-5-deoxystrigol were prepared using PRODRG (Schüttelkopf€ and van Aalten, 2004) and AutoDockTools (Sanner, 1999). Docking was performed with AutoDock Vina (Trott and Olson, 2010). The calculated affinity for (–)-5-deoxystrigol docked into PpKAI2-like E was −7.0 kcal/mol and 7.7 kcal/mol for (+)-5-deoxystrigol. The two 4-deoxyorobanchol enantiomers could not be reliably docked into PpKAI2-like E.

Generation of transgenic plants

The KAI2 promoter region was amplified by using primers as described in Table S2, and the PCR product was cloned into the Hind III site of pGWB1 (Nakagawa et al., 2007) using In-Fusion Cloning Kit (Takara Bio) to yield KAI2Pro-pGWB1. The cDNA of each PpKAI2 was obtained by PCR by using primers as described in Table S2, and each PCR product was subcloned into the entry vector pENTR/D-TOPO (Invitrogen). Each cDNA was shuttled into KAI2Pro-pGWB1 or the 35S promoter vector, pGWB2, respectively, by using LR clonase II according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). Arabidopsis wild-type, atd14–2 (Seto et al., 2014), and kai2–4 (Ume-hara et al., 2015) plants were transformed with the resulting constructs by floral dip using Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Transformed plants (T1) were selected on the half strength Murashige-Skoog (½ MS) agar media containing hygromycin (25 mg/ml). Transgenic lines with single T-DNA insertion were identified in the following generation based on 3:1 segregation of hygromycin resistance (T2). Homozygous transgenic lines were identified in subsequent generations and representative lines were used for further analysis.

Phenotypic analysis of transgenic plants

For evaluation of shoot branching, sterilized seeds were sown on ½ MS agar medium containing 1% sucrose and 0.8% agar (pH 5.7) and grown at 22°C under continuous white light (80 μmol m−2 s−1) for 10 days. Then, seedlings were transferred to soil and grown under the long-day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark, 60 μmol m−2 s−1) for an additional 35 days. The number of axillary buds (> 5 mm) per plant was measured. For evaluation of hypocotyl elongation and KAR1 response, sterilized seeds were sown on ½ MS agar medium (1% sucrose, 0.8% agar, pH 5.7) containing DMSO (mock), 1 μM KAR1 or 10 μM KAR1. The agar plates were placed vertically, and plants were grown at 22°C under short-day conditions (16 h dark/8 h light, 50 μmol m−2 s−1) for 9 days. Then, the length of hypocotyls was measured by using Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012).

Mass spectrometry of PpKAI2-like proteins

Samples were precipitated by methanol/chloroform. Dried pellets were dissolved in 8 M urea/100 mM TEAB, pH 8.5. Proteins were reduced with 5 mM TCEP) and alkylated with 10 mM chloroacetamide. Proteins were digested overnight at 37 C in 2 M urea/100 mM TEAB, pH 8.5 with trypsin. Digestion was quenched with formic acid, 5% final concentration. Digested samples were analyzed on a Fusion Lumos Orbitrap tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo-Fisher). The digest was injected directly onto a 30 cm, 75 μm ID column packed with BEH 1.7 μm C18 resin (Waters). Samples were separated at a flow rate of 400 nl/min on a nLC 1000 (Thermo-Fisher). Buffer A and B were 0.1% formic acid in water and 0.1% formic acid in 90% acetonitrile, respectively. A gradient of 1%–30% B over 180 min, an increase to 50% B over 40 min, an increase to 100% B over 10 min and held at 100% B for a final 10 min of washing was used for 240 min total run time. The column was re-equilibrated with 20 μl of buffer A prior to the injection of sample. Peptides were eluted directly from the tip of the column and nanosprayed directly into the mass spectrometer by application of 2.5 kV voltage at the back of the column. The Orbitrap Fusion was operated in a data dependent mode. Full MS scans were collected in the Orbitrap at 120 K resolution with a mass range of 400 to 1500 m/z and an AGC target of 45. The cycle time was set to 3 s and the most abundant ions per scan were selected for HCD MS/MS in the Orbitrap with an AGC target of 45 and minimum intensity of 50000. Maximum fill times were set to 50 ms and 100 ms for MS and MS/MS scans respectively. Quadrupole isolation at 1.6 m/z was used, monoisotopic precursor selection was enabled, and dynamic exclusion was used with exclusion duration of 5 s. Protein and peptide identification were done with Integrated Proteomics Pipeline – IP2 (Integrated Proteomics Applications). Tandem mass spectra were extracted from raw files using RawConverter (He et al., 2015) and searched with ProLuCID (Xu et al., 2015) against an E. coli protein database with recombinant proteins added. The search space included all fully-tryptic and half-tryptic peptide candidates. Carbamidomethylation on cysteine was considered as a static modification, differential modification of 96.0211 Da was considered on serine and histidine. Data was searched with 50 ppm precursor ion tolerance and 600 ppm fragment ion tolerance. Identified proteins were filtered to using DTASelect (Tabb et al., 2002) and utilizing a target-decoy database search strategy to control the false discovery rate to 1% at the protein level (Peng et al., 2003). Chromatogram and peak area were calculated with Skyline (MacLean et al., 2010).

Mass spectrometry of 5-deoxystrigol

1 μM protein (PpKAI2-like C, D or E) was incubated with 1 mM substrate ((–)-5-deoxystrigol or (+)-5-deoxystrigol) for 3 h at room tem-perature in 20 mM TRIS-HCl, 30 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, final pH 7.7, in a 100 μl volume. Samples were then analyzed on a Dionex Ultimate 3000 LC system (Thermo-Fisher) coupled to a TSQ Quantiva mass spectrometer (Thermo-Fisher) fitted with a Kinetex C18 reversed phase column (2.6 μm, 150 3 2.1 mm i.d., Phenomenex). The following LC solvents were used: Solution A, 0.1% formic acid in water; solution B, 0.1% formic acid in 90% acetonitrile. The column was equilibrated in 20% solution B. Separation was performed in a linear gradient of 20%–100% B in 12 min and re-equilibrated in 20% B for 6 min, at a flow rate of 0.2 ml/min. The sample injection volume was 10 μl, column oven temperature was set to 4°C and the autosampler kept at 4°C. MS analyses were performed using electrospray ionization in positive mode, spay voltages of 3.5 kV, ion transfer tube temperature of 325°C, and vaporizer temperature of 275°C. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) was performed by using precursor mass of the intact compounds (331.2 m/z) and four transitions (97.1, 216.1, 217.1 and 234.1 m/z). Peak areas at retention time of 11.2 min were measured using Skyline (MacLean et al., 2010).

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Seedlings grown at 22°C under continuous light for 10 days (35S:PpKAI2Ls in atd14) or under short-day conditions for 9 days (KAI2:PpKAI2Ls in kai2) were harvested, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until use. Total RNA was extracted from seedlings using a Cica geneus RNA Prep Kit for Plant (KANTO CHEMICAL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover (TOYOBO) in 20 μL of the reaction mixture containing 2 μg of total RNA. A portion (½0 for PpKAI2L genes and 1/100 for actin) of the synthesized cDNA was used to PCR with primer sets described in Table S2. PCRs were carried out by using a T100 thermal cycler (Bio-rad) with KOD Fx Neo (TOYOBO) under the following conditions: denaturing at 98°C for 10 s, primer annealing at 60°C for 30 s and extension at 68°C for 30 s. The number of PCR cycles was 35. The PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Protein concentrations

Protein concentrations were determined measuring absorption at 280 nm on a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo-Fisher).

Analysis of plant phenotypes

Measurements of Arabidopsis hypocotyl lengths was statistically analyzed using a Tukey-Kramer test with a mean n = 7–9 and a p < 0.05 cutoff. Arabidopsis branching assays were statistically analyzed using a Steel-Dwass test with a mean n = 13–14 and a p < 0.05 cutoff.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) data

ITC data was fitted using a one site stoichiometry binding model in Origin (Originlab).

Biochemical protein analyses

Enzymatic parameters were determined using the MichαElis Menten equation in IDBS XLfit. Karrikin binding was analyzed using a one-site dose dependent Levenberg Marquardt fit in Origin (Originlab).

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

The accession numbers for the data reported in this paper are PDB: 6ATX, 6AZB, 6AZC, 6AZD for PpKAI2-like C, PpKAI2-like E, PpKAI2-like E S166A, PpKAI2-like H, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Physcomitrella patens provides an early evolutionary snapshot of 11 KAI2-like proteins

A loop segment determines substrate specificity in Physcomitrella KAI2-like proteins

Distinct groups of proteins perceive (−)-5-deoxystrigol and the karrikin KAR1

Physcomitrella KAI2-like proteins cannot complement Arabidopsis kai2 or d14 mutants

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff at Advanced Light Source at the Berkeley Center for Structural Biology for assistance with X-ray data collection. The Berkeley Center for Structural Biology is supported in part by the NIH, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The Advanced Light Source is supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy (contract DE-AC02–05CH11231). This work was further supported by the Mass Spectrometry Core of the Salk Institute with funding from NIH-NCI CCSG (P30 014195) and the Helmsley Center for Genomic Medicine. Financial support for this work came from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to J.C.). We thank James Moresco, Jolene Diedrich, and Antonio Michel Pinto for technical support. We thank the laboratory of Prof. Kohki Akiyama (Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Osaka Prefecture University) for providing rac-carlactone. J.C. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes four figures and two tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.003.

REFERENCES

- Abe S, Sado A, Tanaka K, Kisugi T, Asami K, Ota S, Kim HI, Yoneyama K, Xie X, Ohnishi T, et al. (2014). Carlactone is converted to car-lactonoic acid by MAX1 in Arabidopsis and its methyl ester can directly interact with AtD14 in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 18084–18089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunköczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. (2010). PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Mustyakimov M, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Zwart PH, and Adams PD (2012). Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 68, 352–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama K, and Hayashi H. (2006). Strigolactones: chemical signals for fungal symbionts and parasitic weeds in plant roots. Ann. Bot. 97, 925–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama K, Matsuzaki K, and Hayashi H. (2005). Plant sesquiterpenes induce hyphal branching in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Nature 435, 824–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder A, Jamil M, Marzorati M, Bruno M, Vermathen M, Bigler P, Ghisla S, Bouwmeester H, Beyer P, and Al-Babili S. (2012). The path from b-carotene to carlactone, a strigolactone-like plant hormone. Science 335, 1348–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andújar-Sánchez M, Las Heras-Vázquez FJ, Clemente-Jiménez JM, Martínez-Rodríguez S, Camara-Artigas A, Rodríguez-Vico F, and Jara-Pérez V. (2006). Enzymatic activity assay of D-hydantoinase by isothermal titration calorimetry. Determination of the thermodynamic activation parameters for the hydrolysis of several substrates. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 67, 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bythell-Douglas R, Rothfels CJ, Stevenson DWD, Graham SW, Wong GK, Nelson DC, and Bennett T. (2017). Evolution of strigolactone receptors by gradual neo-functionalization of KAI2 paralogues. BMC Biol. 15, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen VB, Arendall WB 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, and Richardson DC (2010). MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier F, Nieminen K, Sánchez-Ferrero JC, Rodríguez ML, Chagoyen M, Hardtke CS, and Cubas P. (2014). Strigolactone promotes degradation of DWARF14, an α/β hydrolase essential for strigolactone signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 1134–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn CE, and Nelson DC (2016). Evidence that KARRIKIN-INSENSITIVE2 (KAI2) receptors may perceive an unknown signal that is not karrikin or strigolactone. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn CE, Bythell-Douglas R, Neumann D, Yoshida S, Whittington B, Westwood JH, Shirasu K, Bond CS, Dyer KA, and Nelson DC (2015). Plant evolution. Convergent evolution of strigolactone perception enabled host detection in parasitic plants. Science 349, 540–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CE, Whichard LP, Turner B, Wall ME, and Egley GH (1966). Germination of witchweed (Striga lutea Lour.): isolation and properties of a potent stimulant. Science 154, 1189–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Saint Germain A, Clavé G, Badet-Denisot MA, Pillot JP, Cornu D, Le CαEr JP, Burger M, Pelissier F, Retailleau P, Turnbull C, et al. (2016). An histidine covalent receptor and butenolide complex mediates strigolactone perception. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 787–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker EL, Alder A, Hunn S, Ferguson J, Lehtonen MT, Scheler B, Kerres KL, Wiedemann G, Safavi-Rizi V, Nordzieke S, et al. (2017). Strigolactone biosynthesis is evolutionarily conserved, regulated by phosphate starvation and contributes to resistance against phytopathogenic fungi in a moss, Physcomitrella patens. New Phytol. 216, 455–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaux PM, Xie X, Timme RE, Puech-Pages V, Dunand C, Lecompte E, Delwiche CF, Yoneyama K, Bécard G, and Séjalon-Delmas N. (2012). Origin of strigolactones in the green lineage. New Phytol. 195, 857–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, and Cowtan K. (2010). Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fährrolfes R, Bietz S, Flachsenberg F, Meyder A, Nittinger E, Otto T, Volkamer A, and Rarey M. (2017). ProteinsPlus: a web portal for structure analysis of macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 (W1), W337–W343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flematti GR, Waters MT, Scaffidi A, Merritt DJ, Ghisalberti EL, Dixon KW, and Smith SM (2013). Karrikin and cyanohydrin smoke signals provide clues to new endogenous plant signaling compounds. Mol. Plant 6, 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flematti GR, Scaffidi A, Waters MT, and Smith SM (2016). Stereospecificity in strigolactone biosynthesis and perception. Planta 243, 1361–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Roldan V, Fermas S, Brewer PB, Puech-Pagès V, Dun EA, Pillot JP, Letisse F, Matusova R, Danoun S, Portais JC, et al. (2008). Strigolactone inhibition of shoot branching. Nature 455, 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Zheng Z, La Clair JJ, Chory J, and Noel JP (2013). Smoke-derived karrikin perception by the α/β-hydrolase KAI2 from Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 8284–8289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamiaux C, Drummond RS, Janssen BJ, Ledger SE, Cooney JM, Newcomb RD, and Snowden KC (2012). DAD2 is an α/β hydrolase likely to be involved in the perception of the plant branching hormone, strigolactone. Curr. Biol. 22, 2032–2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen LD, Transtrum MK, Quinn C, and Demarse N. (2016). Enzyme-catalyzed and binding reaction kinetics determined by titration calorimetry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1860, 957–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Diedrich J, Chu YY, and Yates JR 3rd. (2015). Extracting accurate precursor information for tandem mass spectra by RawConverter. Anal. Chem. 87, 11361–11367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann B, Proust H, Belcram K, Labrune C, Boyer FD, Rameau C, and Bonhomme S. (2014). Strigolactones inhibit caulonema elongation and cell division in the moss Physcomitrella patens. PLoS ONE 9, e99206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, and Rosenström P. (2010). Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D.Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–W549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. (2010). Xds. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagiyama M, Hirano Y, Mori T, Kim SY, Kyozuka J, Seto Y, Yamaguchi S, and Hakoshima T. (2013). Structures of D14 and D14L in the strigolactone and karrikin signaling pathways. Genes Cells 18, 147–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Obando M, Conn CE, Hoffmann B, Bythell-Douglas R, Nelson DC, Rameau C, and Bonhomme S. (2016). Structural modelling and transcriptional responses highlight a clade of PpKAI2-LIKE genes as candidate receptors for strigolactones in Physcomitrella patens. Planta 243, 1441–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Obando M, de Villiers R, Hoffmann B, Ma L, de Saint Germain A, Kossmann J, Coudert Y, Harrison CJ, Rameau C, Hills P, and Bonhomme S. (2018). Physcomitrella patens MAX2 characterization suggests an ancient role for this F-box protein in photomorphogenesis rather than strigolactone signalling. New Phytol. 219, 743–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean B, Tomazela DM, Shulman N, Chambers M, Finney GL, Frewen B, Kern R, Tabb DL, Liebler DC, and MacCoss MJ (2010). Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics 26, 966–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, and Read RJ (2007). Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Cryst. 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNicholas S, Potterton E, Wilson KS, and Noble ME (2011). Presenting your structures: the CCP4mg molecular-graphics software. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 386–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morffy N, Faure L, and Nelson DC (2016). Smoke and hormone mirrors: action and evolution of karrikin and strigolactone signaling. Trends Genet. 32, 176–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Kurose T, Hino T, Tanaka K, Kawamukai M, Niwa Y, Toyooka K, Matsuoka K, Jinbo T, and Kimura T. (2007). Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 104, 34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H, Xue YL, Miyakawa T, Hou F, Qin HM, Fukui K, Shi X, Ito E, Ito S, Park SH, et al. (2013). Molecular mechanism of strigolactone perception by DWARF14. Nat. Commun. 4, 2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DC, Scaffidi A, Dun EA, Waters MT, Flematti GR, Dixon KW, Beveridge CA, Ghisalberti EL, and Smith SM (2011). F-box protein MAX2 has dual roles in karrikin and strigolactone signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 8897–8902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Elias JE, Thoreen CC, Licklider LJ, and Gygi SP (2003). Evaluation of multidimensional chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/LC-MS/MS) for large-scale protein analysis: the yeast proteome. J. Proteome Res. 2, 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proust H, Hoffmann B, Xie X, Yoneyama K, SchαEfer DG, Yoneyama K, Nogue FC (2011). Strigolactones regulate protonema branching and act as a quorum sensing-like signal in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Development 138, 1531–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remy W, Taylor TN, Hass H, and Kerp H. (1994). Four hundred-million-year-old vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizαE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 11841–11843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanner MF (1999). Python: a programming language for software integration and development. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 17, 57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaffidi A, Waters MT, Sun YK, Skelton BW, Dixon KW, Ghisalberti EL, Flematti GR, and Smith SM (2014). Strigolactone hormones and their stereoisomers signal through two related receptor proteins to induce different physiological responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 165, 1221–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüttelkopf AW, and van Aalten DM (2004). PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 1355–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto Y, Sado A, Asami K, Hanada A, Umehara M, Akiyama K, and Yamaguchi S. (2014). Carlactone is an endogenous biosynthetic precursor for strigolactones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 1640–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun XD, and Ni M. (2011). Hyposensitive to light, an alpha/beta fold protein, acts downstream of elongated hypocotyl 5 to regulate seedling deetiolation. Mol. Plant 4, 116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabb DL, McDonald WH, and Yates JR 3rd. (2002). DTASelect and Contrast: tools for assembling and comparing protein identifications from shotgun proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 1, 21–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger TC, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Afonine PV, Moriarty NW, Zwart PH, Hung LW, Read RJ, and Adams PD (2008). Iterative model building, structure refinement and density modification with the PHENIX AutoBuild wizard. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 64, 61–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh S, Holbrook-Smith D, Stogios PJ, Onopriyenko O, Lumba S, Tsuchiya Y, Savchenko A, and McCourt P. (2015). Structure-function analysis identifies highly sensitive strigolactone receptors in Striga. Science 350, 203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O, and Olson AJ (2010). AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya Y, Yoshimura M, Sato Y, Kuwata K, Toh S, Holbrook-Smith D, Zhang H, McCourt P, Itami K, Kinoshita T, and Hagihara S. (2015). Parasitic plants. Probing strigolactone receptors in Striga hermonthica with fluorescence. Science 349, 864–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umehara M, Hanada A, Yoshida S, Akiyama K, Arite T, Takeda-Kamiya N, Magome H, Kamiya Y, Shirasu K, Yoneyama K, et al. (2008). Inhibition of shoot branching by new terpenoid plant hormones. Nature 455, 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umehara M, Cao M, Akiyama K, Akatsu T, Seto Y, Hanada A, Li W, Takeda-Kamiya N, Morimoto Y, and Yamaguchi S. (2015). Structural requirements of strigolactones for shoot branching inhibition in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 1059–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters MT, Scaffidi A, Flematti G, and Smith SM (2015a). Substrate-induced degradation of the α/β-fold hydrolase KARRIKIN INSENSITIVE2 re-quires a functional catalytic triad but is independent of MAX2. Mol. Plant 8, 814–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters MT, Scaffidi A, Moulin SL, Sun YK, Flematti GR, and Smith SM (2015b). A Selaginella moellendorffii ortholog of KARRIKIN INSENSITIVE2 functions in Arabidopsis development but cannot mediate responses to karrikins or strigolactones. Plant Cell 27, 1925–1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X, Yoneyama K, Kisugi T, Uchida K, Ito S, Akiyama K, Hayashi H, Yokota T, Nomura T, and Yoneyama K. (2013). Confirming stereochemical structures of strigolactones produced by rice and tobacco. Mol. Plant 6, 153–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Park SK, Venable JD, Wohlschlegel JA, Diedrich JK, Cociorva D, Lu B, Liao L, Hewel J, Han X, et al. (2015). ProLuCID: an improved SEQUEST-like algorithm with enhanced sensitivity and specificity. J. Proteomics 129, 16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Miyakawa T, Nosaki S, Nakamura A, Lyu Y, Nakamura H, Ohto U, Ishida H, Shimizu T, Asami T, and Tanokura M. (2018). Structural analysis of HTL and D14 proteins reveals the basis for ligand selectivity in Striga. Nat. Commun. 9, 3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao R, Ming Z, Yan L, Li S, Wang F, Ma S, Yu C, Yang M, Chen L, Chen L, et al. (2016). DWARF14 is a non-canonical hormone receptor for strigolactone. Nature 536, 469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama K, Xie X, Yoneyama K, Kisugi T, Nomura T, Nakatani Y, Akiyama K, and McErlean CSP (2018). Which are the major players, canonical or non-canonical strigolactones? J. Exp. Bot. 69, 2231–2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao LH, Zhou XE, Wu ZS, Yi W, Xu Y, Li S, Xu TH, Liu Y, Chen RZ, Kovach A, et al. (2013). Crystal structures of two phytohormone signal-transducing α/β hydrolases: karrikin-signaling KAI2 and strigolactone-signaling DWARF14. Cell Res. 23, 436–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer AD, Lang D, Buchta K, Rombauts S, Nishiyama T, Hasebe M, Van de Peer Y, Rensing SA, and Reski R. (2013). Reannotation and extended community resources for the genome of the non-seed plant Physcomitrella patens provide insights into the evolution of plant gene structures and functions. BMC Genomics 14, 498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The accession numbers for the data reported in this paper are PDB: 6ATX, 6AZB, 6AZC, 6AZD for PpKAI2-like C, PpKAI2-like E, PpKAI2-like E S166A, PpKAI2-like H, respectively.