Abstract

Fluorescent sensors benefit from high signal-to-noise and multiple measurement modalities, allowing for a multitude of applications and flexibility of design. Semiconductor nanocrystal quantum dots (QDs) are excellent fluorophores for sensors because of their extraordinary optical properties. They have high thermal and photochemical stability compared to organic dyes or fluorescent proteins and are extremely bright due to their large molar cross-sections. In contrast to organic dyes, QD emission profiles are symmetric, with relatively low full width half maxima. In addition, the size tunability of their emission color, which is a result of quantum confinement, make QDs exceptional emitters with high color purity from the ultra-violet to near infrared wavelength range. The role of QDs in sensors ranges from simple fluorescent tags, as used in immunoassays, to intrinsic sensors that utilize the inherent photophysical response of QDs to fluctuations in temperature, electric field or ion concentration. In more complex configurations, QDs and biomolecular recognition moieties like antibodies are combined with a third component to transduce the optical signal via energy transfer. QDs can act as donors, acceptors, or both in energy transfer-based sensors using Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), nanometal surface energy transfer (NSET), or charge or electron transfer. The changes in both spectral response and photoluminescent lifetimes have been successfully harnessed to produce more sensitive sensors and multiplexed devices. While technical challenges related to biofunctionalization and the high cost of laboratory-grade fluorimeters have thus far prevented broad implementation of QD-based sensing in clinical or commercial settings, improvements in bioconjugation methods and detection schemes, including using simple consumer devices like cell phone cameras, are lowering the barrier to broad use of more sensitive QD-based devices.

Keywords: Quantum Dots, Fluorescent Sensors, intrinsic sensors, ELISA, FLISA, FRET, energy transfer, ratiometric sensors

1. Introduction

Fluorescence is a powerful tool for imaging and detection. Its superior signal-to-noise (S/N) compared to other optical techniques and the multiple photophysical measurement approaches lend it to numerous applications, including sensing. Photon energy (i.e., wavelength/color), photoluminescence (PL) intensity, and PL lifetime can all be modified and thus harnessed as sensor outputs [1]. Numerous fluorophores including organic dyes, fluorescent proteins, and lanthanide-based emitters have been coupled to signal transduction elements to produce fluorescent sensors [2], but in this review, we specifically discuss the role of semiconductor quantum dots (QDs) in the field. Photophysically, the simplest QD-based sensors use the unmodulated emission of QDs as an indication of whether or not a QD-tagged moiety is present, such as when fluorescence aids visualization [3] or indicates the binding of a QD-labeled biomolecule [4–7]. Alternatively, intrinsic photophysical mechanisms can be harnessed to tie specific environmental factors such as temperature to calibrated changes in the QD emissive properties. In this way, the QD itself becomes both the sensor and transduction element and changes in the environment are quantified through changes in PL intensity, wavelength, or lifetime [8–20]. Using additional quenchers or fluorophores to modulate QD photophysics in energy transfer schemes adds another layer of complexity to the sensors that enables specific detection of analytes through molecular recognition elements [21–31]. The nanoparticle structure of QD-based sensors facilitates the integration of multiple sensing and modulating elements [32, 33], allowing for complex or multiplexed signaling [24, 28, 34–37]. In this review, we discuss the underlying photophysics supporting the various sensor types as well as examples that demonstrate applications of each method.

2. Quantum Dot Fundamentals

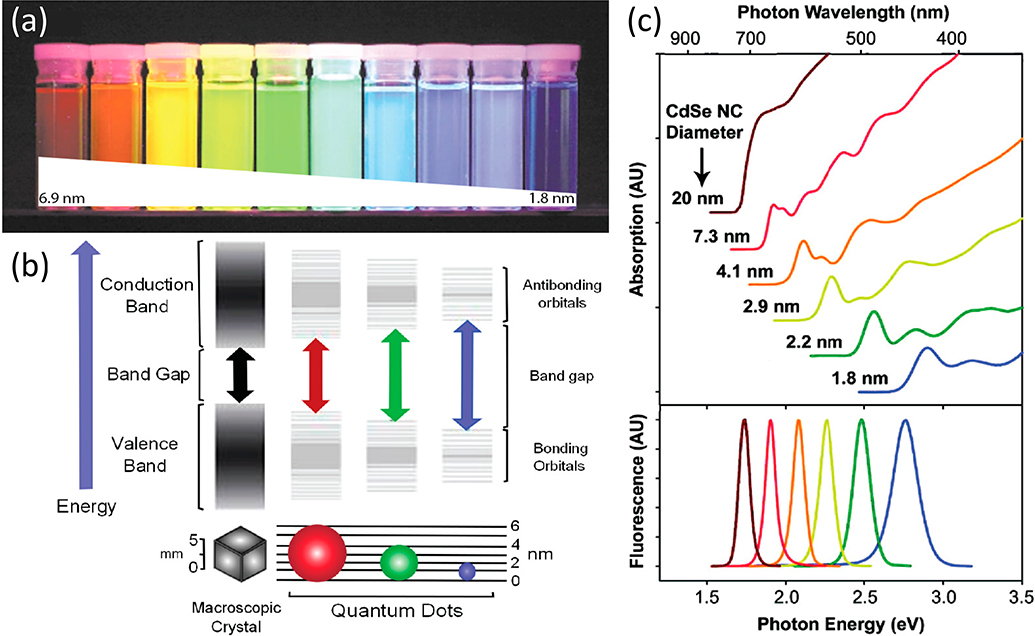

Quantum dots (QDs) are semiconductor nanocrystals exhibiting fluorescent properties due to quantum confinement. Quantum confinement occurs when a material is reduced to a size similar to the characteristic length of the property being probed [39]. For QDs, this characteristic length is the exciton Bohr radius (the distance between the electron-hole pair), thus QDs on the same size scale as their material’s characteristic exciton Bohr radius exhibit quantum confinement [40, 41]. QD fluorescence originates from the recombination of an electron-hole pair, and fluorescence is initiated by the photoexcitation of an electron from the QD valence band into its conduction band. The electron relaxes to the lowest energy level in the conduction band before recombining with the hole left behind in the valence band. The difference in energy between the conduction and valence band is conserved in the form of an emitted photon, thus, the size of this gap dictates the energy/wavelength of the light emitted from the QD [38, 39, 42] (figure 1). The QD bandgap is directly related to its diameter, and therefore QDs comprising the same semiconductor material are can be tuned to emit different wavelengths by simply changing their size. More recently, QDs made of different types of materials have been synthesized, such as graphene [43] and silicon [44], but this review will focus specifically on semiconductor metal QDs.

Figure 1:

(a) Quantum dots of different sizes emitting at colors across the visible wavelength range. (b) A diagram showing quantization of energy levels in semiconductor crystals as they decrease in size on the nanoscale. (c, top) Absorption and (c, bottom) emission spectra of CdSe QDs of different sizes. QDs have broadband absorption above their bandgap and exhibit symmetric emission profiles. Reprinted from Ref. [38]. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License 4.0 (CC BY-NC)

3. Quantum Dots as Indicator Dyes in Sensors

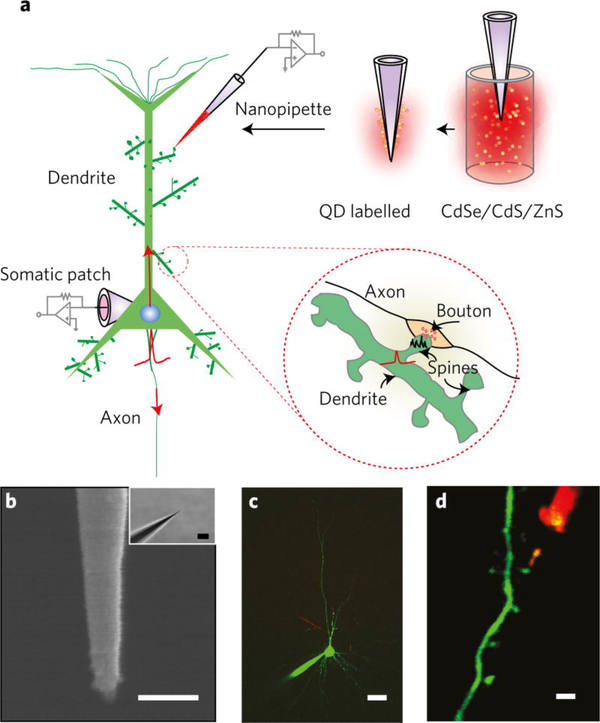

An advantage of QDs compared to other fluorophores is their large absorption cross-section. Brightness is determined by the amount of light a molecule can absorb (molar extinction coefficient, ε) and the efficiency with which the absorbed energy is converted into emitted light (quantum yield, QY) [45]. While both organic fluorophores and QDs may exhibit near unity QYs, the absorption cross-section of QDs may be orders of magnitude higher [46]. Heterostructured core/shell QDs provide further opportunity to tailor the absorption cross-sections of QDs leading to brightness-matched multicolor QDs and brightness-enhanced thick-shelled QDs [25, 47]. The brightness of QDs make them an effective choice when picking fluorescent labels to tag objects. For example, nanopipettes used for taking voltage recordings of dendritic spines have been coated with QDs to enable clear visualization of the pipettes for precise placement on cell structures (figure 2) [3]. While QDs were not the focus of the scientific questions being studied, they were used effectively as a tool to facilitate its experimental methods.

Figure 2:

QD-coated nanopipettes used for taking voltage recordings of dendritic spines. Coating the nanopipettes with red QDs allowed for precise placement of the nanopipette. Reprinted by permission from Ref. [3] Copyright 2016 Springer Nature.

As in the nanopipette example, QDs incorporated into existing visualization schemas as alternatives to organic dyes or fluorescent proteins are effective indicators in sensing platforms. QDs have generated interest as alternative fluorescent labels due to their excellent chemical- and photostability, narrow bandwidths, exceptional brightness, and large surface area available for surface functionalization [33, 46, 48]. In sensors, the binding or unbinding of a species is monitored by fluorescently labeling one or more of the parts involved in the interaction. Binding/unbinding changes the concentration of the fluorophore in the visualized region, resulting in a change in fluorescence intensity. A common, widely used sensing format based on this scheme is the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). ELISAs use antibody binding to detect a target antigen or antibody with enzyme catalyzed colorimetric reactions used to indicate the presence of the bound antibody. Assays that utilize a fluorescent label instead eliminate the incubation time necessary to develop the color and are called fluoroimmunoassays or FLISAs. Generally, fluorescence assays have higher signal to noise ratios than colorimetric assays, resulting in lower limits of detection (LOD) [49]. For example, ThermoFisher Scientific sells a broad range of immunosorbent assay products using both colorimetric and fluorescent detection methods. Currently, the lowest detectable concentration for a colorimetric product is 20 pg/mL (Ultra TMB, 34028) while all fluorescence based ELISAs have LODs < 5 pg/mL, with the lower limit of the QuantaRed Enhanced Chemifluorescent Substrate assay reaching 4 pg/mL [50].

An advantage of using QDs instead of dyes or catalysts is the availability of their relatively large nanoparticle surface for a variety of functionalization schemes. Self-assembly mechanisms are used to bind biomolecules to the metal ion surface of the QD, making for flexible and relatively simple labeling. Perhaps one of the first examples of self-assembled antibody/QD conjugates (Ab-QDs) and their use in a FLISA was shown by Goldman et al. [51]. In their design, antibodies were engineered to include positively charged leucine zippers for electrostatic interaction and self-assembly to QDs coated with the negatively charged small molecule ligand dihydrolipoic acid (DHLA). Shortly after their publication, histidine self-assembly to the QD metal ion surface was reported [52]; since the antibodies used in the Goldman report utilized histidine domains to facilitate protein purification, the exact mechanism of binding to the QD surface is unclear. Nevertheless, the utility of the Ab-QDs was demonstrated in both direct and sandwich fluorometric assays of Staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) as well as in plate-based and flow-displacement formats for TNT sensing. While direct comparison to commercially available FLISAs/ELISAs was not performed, the feasibility of the QD-FLISA system was successfully demonstrated [51].

Compared to colorimetric ELISAs or organic dye-based FLISAs, QDs present tremendous multiplexing potential. Due to their broadband absorption in the UV, multiple QDs emitting at distinct wavelengths can be excited with a single excitation wavelength. In 2009, Peng et al. created an assay incorporating five distinct QD emitters per well for simultaneous detection of substances often illegally used on food animals in China: dexamethasone, gentamicin, clonazepam, medroxyprogesterone, and ceftiofur [7]. Each of the QDs were functionalized through self-assembly with biotinylated, denatured BSA before further functionalization with an avidin-labeled antibody. While the binding capacity of the Abs was significantly reduced when attached to QDs, the FLISA was still used to detect each species in relevant concentration ranges with less than 0.1% cross-reactivity between the chemically distinct analytes. Following drug administration, animal tissue was harvested and homogenized after 1, 2, 3 and 7 days. Liquid sample extracts were tested with the FLISA and the values quantified were within reasonable agreement for dexamethasone and within a standard deviation for medroxyprogesterone acetate compared to the results from a traditional ELISA.

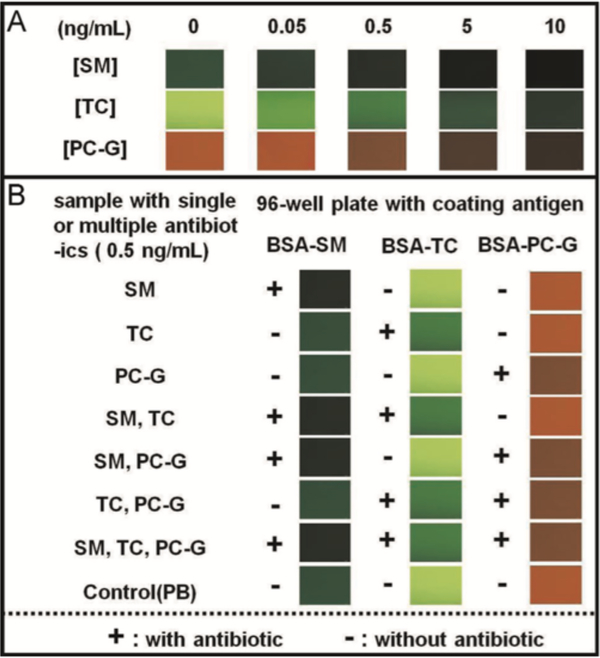

Using the antibody binding scheme presented by Peng et al. [7], Zhu et al. developed a multiplexed hybrid assay using both commercial QDs and horse radish peroxidase (HRP) for sensing [6]. This hybrid immunoassay was used for simultaneous detection of quinolone and sulfonamides in milk samples. The design incorporated both direct and indirect binding, along with both fluorescence and colorimetric based sensing in a single well. Another multi-color QD-FLISA reported by Song et al. in 2015 detected the residues of multiple antibiotics in milk. Their competitive fluorescence immunoassay consisted of antibodies that bound to the well plate in the absence of the antibiotics of interest. Rather than mixing all antibiotic-antibody pairs into a single well, a fluorescence imaging array was used to simultaneously measure 96 wells at once. Specific responses to each antibiotic were observed in milk samples with good sensitivity and accuracy when compared to results of the same samples tested with traditional ELISAs. The authors noted that in addition to quantitative fluorescent measurements, semi-quantitative information could be obtained from visual inspection and a standard color chart. The demonstration of these color charts (figure 3) show potential for translation of the sensor to a detection system for daily food safety control [53]. Because the different antibody-antibiotic pairs are never mixed in the same well, different QD colors were not actually necessary. However, since all of the QDs could be excited at the same wavelength, the incorporation of multiple colors eases visual inspection with no extra measurement steps, something that would not be possible when using traditional fluorophores with smaller Stokes shifts. More recently, a FLISA was developed for detection of C-reactive protein (CRP) [4], a critical biomarker for cardiac infarct. CdSe/ZnS QDs coated with an amphiphilic polymer, polymaleic acid n-hexadecanolester (PMAH), and covalently labeled with antibodies through carbodiimide crosslinker chemistry were used as labels. Clinical samples were collected and used in both the developed FLISA and the gold standard Roche immunoturbidimetry assay. The FLISA showed excellent accuracy. Immunoturbidimetry is a method of protein quantification that relies on the formation of antigen-antibody complexes that precipitate from solution; the turbidity of the solution is measured to quantify protein content. Immunoturbidimetry is fast and sensitive, but requires expensive instrumentation; ELISAs are economical by comparison, but often take longer than an hour to develop [54]. The total time required for the FLISAs was 50 mins, shorter than a typical ELISA assay, showing potential for development into a rapid and cost-effective diagnostic tool [4].

Figure 3:

A color chart for visual, qualitative determination of streptomycin (SM), tetracycline hydrochloride (TC), and penicillin G (PC-G) concentrations in milk. Panel (a) provides a color-key for comparison to the colors collected from real samples in panel (b). All wells with antibiotics show a visual change in color from their non-antibiotic controls. Figure reprinted with permission from Ref. [53], Copyright 2015 Elsevier.

Plate-based ELISAs have been standard in clinical labs for over 20 years [55], but their assay protocols involve several washing and incubation steps that require time and expertise. The advantage, however, is precise quantification of the analyte of interest. In some cases, precise quantification is not needed, and testing for relevant clinical thresholds for disease is enough to yield a yes-no diagnosis. In these cases, point-of-care (POC) devices can be particularly useful. POCs devices are meant for diagnostic screening at or near the patient site of care. To be effective, they must be affordable, reliable, and user friendly [56].

Lateral flow assays (LFAs) are well established as POC devices. LFAs are paper strip sensors that require very little sample and no washing steps. They consist of a sample pad, a conjugate pad, a membrane, and an absorbent pad. The liquid analyte is applied to the sample pad and flows towards the absorbent pad via capillary action. In the presence of the analyte of interest, the conjugate reporter binds to capture strips along the pad, indicating whether the sample is positive or negative for the analyte in question. Traditionally, LFAs use colloidal gold or latex particles. By using quantum dots as a fluorescent readout, the sensitivity of existing LFAs is improved [49]. Several QD based FLAs have been demonstrated for the detection of different viruses [57, 58], biomarkers [4, 59–62], and food contaminants [49, 63].

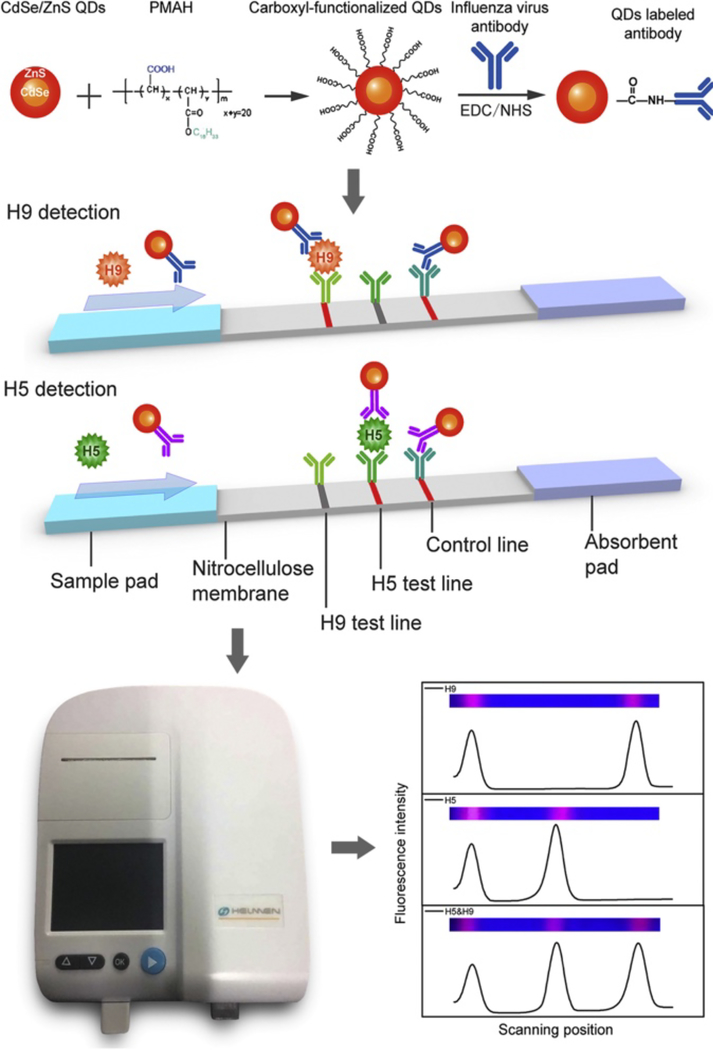

In 2016, Wu et al. developed a QD FLISA-based flow strip assay for detection of 2 influenza subtypes, H5 and H9 (figure 4). Assay strips were fabricated by painting stripes of the H5 and H9 antibodies as well as a control IgG antibody onto commercially available nitrocellulose membrane. 147 samples collected by the Shenzhen Entry–Exit Inspection and Quarantine Bureau were tested with both the FLISA and real-time polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) as a reference. Rather than employing a conjugate pad on the strip, each sample was pre-mixed with the H9 and H5 Ab-QDs before loading onto the sample pad. The results from the two assays matched 100%, verifying the accuracy of the QD-FLISA. While real-time PCR can take several hours, the flow strip could be read out 15 minutes after the sample is applied, greatly shortening the time between sample collection and result [58]. For point-of-care diagnostics, it is important that the time to sensor output fits within a reasonable clinical appointment time to ensure that any relevant diagnoses are relayed to the patient before they leave the clinic to facilitate appropriate and timely treatment [64].

Figure 4:

Schematic of a flow-strip based QD-FLISA for H5N1 and H9N2. CdSe/ZnS QDs functionalized with the polymer PMAH are labeled with antibodies for either H5 or H9 and allowed to travel across the nitrocellulose membrane. In the presence of H9 or H5, the Ab-QDs form a sandwich complex with their respective antibodies dried onto the test strip. QDs not bound by H5N1 or H9N2 are captured on the control line (IgG). Because test lines for each influenza subtype are spatially separated, only 1 QD color needs to be used. The LFA can be read visually or in an instrument for improved LODs. Figure reprinted with permission from Ref. [58], Copyright 2015 Elsevier.

The cost of a diagnostic is determined by the cost of consumables per assay, time per assay, and the instruments needed to analyze the assay. While fluorescent readouts can increase assay sensitivity, the tradeoff is the cost of requisite equipment needed to measure fluorescence. The quality of a fluorimeter greatly influences its price, but even the simplest fluorimeters are benchtop instruments. The development of compact, mobile, and economical devices for measuring fluorescence would greatly advance QD based diagnostics, especially for POC formats. To this end, a recent push for developing ways to take fluorescent measurements with readily available consumer devices such as cell phones has been seen in the field [55, 64–68].

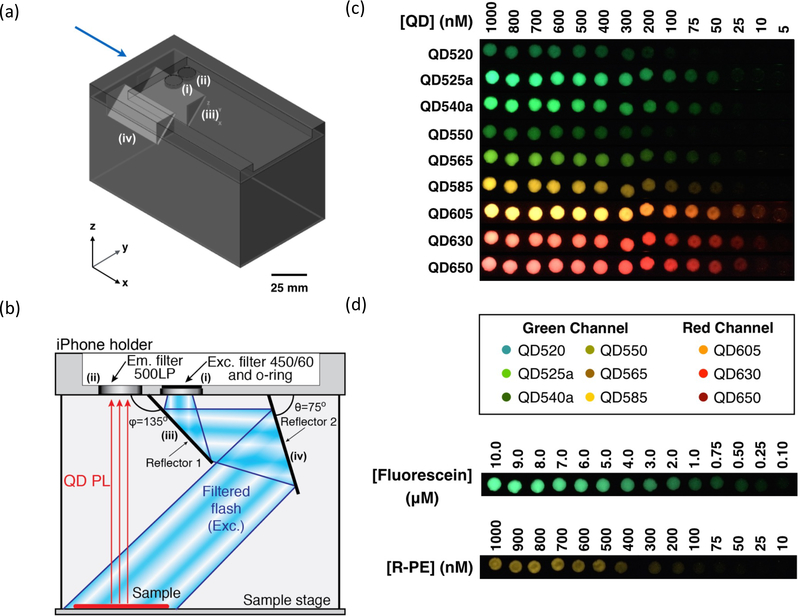

For example, in 2016 Petryayeva and Algar demonstrated the feasibility of using a smartphone, 3D printed holder, two optical filters, and low-cost plastic reflectors for imaging QDs on a variety of substrates [68]. A test streptavidin-biotin binding assay as well as a Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) based proteolytic assay showed the feasibility of using smartphones as an application-based fluorescence imaging tool. Additionally, a comparison to the commonly used dyes fluorescein and R-phycoerythrin (R-PE) showed that the detectable concentration of QDs were approximately an order of magnitude lower. In this comparison, the brightness mismatch between differently colored QDs also became apparent, indicating the need to create brightness matched QDs across different emission wavelengths (figure 5). Nonetheless, this report nicely highlighted the advantage of using bright and photostable QDs when developing cheap imaging platforms based on readily accessible consumer devices.

Figure 5:

(a) CAD drawing of a 3D-printed holder and (b) schematic of the internal functionality of the smartphone fluorescence imager. (c) Images of different QD emitters at different concentrations (4 nM – 1 μM) compared to (d) fluorescein (100 nM – 10 μM) and R-PE (10 nM – 1 μM). Adapted with permission from Ref. [68], Copyright 2016 Springer Nature.

4. Quantum Dots as Intrinsic Sensors

In the sensors previously discussed, the sensing mechanism is external to the QD. In this section, the sensors utilize changes in fluorescence due to properties characteristic to the QDs themselves.

4.1. Using QD Photophysics for Thermometry

Regardless of material type, fluorescent emitters exhibit temperature-dependent fluctuations in their emission intensity [45, 69]. Fluorescent particles absorb light as energy and dissipate that energy radiatively as emitted light, or non-radiatively through various other pathways. The rate of non-radiative transitions, knrt, is dependent on temperature following the Arrhenius equation [45, 69]:

| Eqn. 1 |

where ΔE is the size of the energy gap between the lowest level excited state and non-radiative decay state and k is the Boltzmann constant. If the rate of non-radiative transitions increases, the efficiency of light conversion decreases, resulting in a decrease in emission intensity. In addition to PL intensity, the emission profile with respect to wavelength can also change as a function of temperature. Semiconductor bandgaps, Eg, are temperature dependent and can be loosely described by the Varshni relation [70],

| Eqn. 2 |

where E0 is the semiconductor’s inherent bandgap, T is temperature and α and β are fitting parameters characteristic to the semiconductor. Just as in bulk semiconductors, QD bandgaps, and therefore their PL energy/wavelength, are affected by temperature. Several different core, core/shell, and alloyed QD structures have been studied for fluorescence temperature dependence including CdSe [71, 72], CdTe [73], ZnSe/ZnS [74], CdHgTe [75], InGaN [76], HgTe [77], and alloyed core CdSeZnS/ZnS[78] QDs. Other factors that can impact how temperature affects emission include the presence of dopants [79, 80], different surface ligands [81, 82], and the surrounding environment/matrix [79, 83].

As early as 1996, Dieguéz et al. [79] used photoreflectance studies to show that the Varshni relation is valid for CdTe nanocrystals for the entire temperature range tested (14 – 400K). By measuring the temperature-dependent PL of three different sizes of CdTe QDs, Morello et al. [73] examined not only the quantum confinement-based bandgap changes as a function of temperature, but also changes in the QD fluorescence intensity. Each of the QDs exhibited a decrease in fluorescence intensity, increase in the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the emission peak, and red-shift in peak PL wavelength with increased temperature. Their results were categorized in two temperature regimes: <170 K and >170K. At low temperatures, PL quenching was attributed to a transition between intrinsic energy states and defect states. At temperatures above 170 K, thermal escape, a process mediated by exciton-optical phonon interaction, was observed. The amount of PL quenching was highly dependent on QD size, with larger QDs exhibiting increased exciton-phonon coupling. In 2005, Valerini et al. showed that the change in PL emission wavelength is due to exciton-phonon coupling rather than confinement energy of the exciton [84]. The change in the QD bandgap of CdSe and CdSe/ZnS QD immobilized in polystyrene (PS) was fitted to the Varshni relation and the values for alpha and beta were found to be in range of previously reported values for bulk CdSe. The similarity of temperature dependence to bulk CdSe indicated that QD confinement potentials are independent of temperature, but that exciton-phonon coupling is strongly affected by quantum confinement.

In addition to size, the QD structure and the presence or absence of dopants can impact the temperature dependence of the photoluminescence. A study comparing core only CdTe QDs and core/shell CdTe/CdSe QDs of different CdSe thicknesses [85] showed that temperature-dependent PL quenching was enhanced as the CdSe shell thickness increased. This was attributed to the increased Type II nature of the QDs with increased shell size. In a Type II QD heterostructure, the electron and hole are spatially separated, decreasing the Coulomb interaction between them. This results in a lower activation energy for exciton decomposition, increasing the effect of temperature on PL intensity. Surprisingly, the typical red-shift in PL was not observed for the Type II CdTe/CdSe QDs. The authors speculated that the core/shell interface experiences atomic interdiffusion at high temperature, which should result in a blue-shift in the PL emission. They argued that in their system, the two effects may have canceled each other out. PL measurements with temperature hysteresis curves were not generated for their study, so the validity of this explanation is unclear. The effect of lattice strain due to the difference in lattice parameters of CdTe and CdSe is also discussed, but does not explain the behavior seen in their study, as CdSe/ZnS QDs, which also have high lattice strain, show temperature dependence of PL wavelength [84]. As early as 1996, Pal et al. [79] showed that bandgap temperature dependence on germanium-doped CdTe QDs is well described by the Varshni equation, while this is not the case for vandium-doped CdTe QDs. More recently, Harbord et al. [80] reported that the radiative lifetime of undoped InAs/GaAs increased by 3 ns between 12 and 300 K, whereas this increase was suppressed by a factor of two by p-doping the structure.

In contrast to the previously discussed papers, Reznitsky et al. [86] explored how temperature dependence is impacted by excitation power in a study of five epitaxially grown CdTe/ZnTe quantum wells (QWs)grown with various CdTe thickness separated by 60 nm-thick ZnTe barriers. Samples exposed to lower excitation density (1 W/cm2) were much more susceptible to losses in PL intensity at higher temperatures compared to samples exposed to higher excitation density (100 W/cm2). The effect was lessened as the size of the CdTe layer increased due to the increase in non-radiative pathways for the less well confined structures. PL quenching occurs with an increase in the rate of non-radiative relaxation (eqn. 1) and the authors assert that by exciting at a higher power density, more of these pathways are saturated, resulting in decreased temperature dependence. Although the explanation is satisfying, PL lifetime measurements were not reported to verify this mechanism. While this report was quite short, and the temperature dependence was described simply as “complicated,” the qualitative observation of power dependence is of interest for sensor device design. These results are a reminder that careful experimental design and calibration is necessary to ensure that observations of changes in PL intensity, lifetime, or wavelength are due to the parameter being measured, like temperature, and not confounding factors such as a change in QD concentration or excitation power. Follow-up studies using colloidal QDs would help to elucidate the effect of excitation power on PL temperature dependence.

The temperature-dependent PL properties of QDs naturally lend them to optical temperature sensing. Optical sensors are advantageous for temperature sensing with high spatial resolution without requiring an invasive temperature probe [8, 9, 12]. Methods of incorporating QDs into devices as temperature sensors range from simple to rather complicated, depending on the application. In a simple case, commercially available CdSxSe1-x/ZnS QDs dispersed in toluene were mixed with VGE-7021 varnish to produce a paint that could be applied easily to surfaces [10]. This QD paint was used for real time temperature sensing during magic-angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (MAS NMR) measurements. The outer surface of the MAS rotor was coated with the QD paint and a simple optical fiber was rigged for excitation and collection of QD PL. Low temperature NMR has several motivations [87–89], but can be problematic due to large temperature gradients within the NMR probe, making it important to monitor the temperature of the sample during measurement for accurate analysis. The QD paint showed a PL peak redshift of 18 nm from 10 K to 323 K and was used to determine the temperature during MAS NMR measurements. Temperature measurements below 50 K were subject to error due to the small change in PL wavelength in that regime. While some methods for determining NMR temperature do exist, the QD paint is external to the sample, eliminating contamination, and can be monitored while NMR is in progress. For temperatures below 50 K, the author noted that perhaps a different type of QD could be used that is more responsive to temperature in that range.

The idea of embedding a fluorophore in a matrix to create a ‘paint’ for temperature sensing is not new. In fact, temperature sensitive paints (TSPs) traditionally use small molecule dyes or chemical complexes and are historically used in aerodynamic studies for understanding heat transfer dynamics [90, 91]. A potential benefit of using QDs is their narrow emission bandwidths and broadband UV absorbance profiles. For example, Kameya et al. used ZnS-AgInS2 nanoparticles (ZAIS) in conjunction with platinum tetrakis (pentafluorophenyl) porphyrin (PtTFPP) for dual temperature and pressure sensing [11]. ZAIS was chosen for the TSP because it could be excited using the same wavelength as PtTFPP while exhibiting negligible emission overlap; this spectral separation would be difficult to achieve in a two-dye system. Matsuda et al. also examined ZAIS nanoparticles as temperature sensors, touting the additional benefit of their low toxicity [92].

In some cases, the structure to be coated is complex and a more involved strategy for integrating the QDs is needed. For example, Larrión et al. coated the inner surfaces of the holes of a photonic crystal fiber by means of a layer by layer adsorption technique [93]. Their studies showed that monitoring changes in PL FWHM had a higher average sensitivity than monitoring PL wavelength or intensity. Additionally, it was shown that the sensitivity decreased at lower temperature when looking at PL measurements while the opposite was true when looking at absorbance measurements. While a discussion of absorbance is not included in the scope of this review, the authors make a good point about combining absorbance and fluorescence recordings to maximizing the temperature range in which accurate sensing is possible—a workaround that does not require finding a different type of QD with a more sensitive temperature dependence at low T [93].

In 2010, Bensalah et al. showed that measurement of QD PL emission can accurately monitor gold nanoshell (GNS)-mediated temperature changes occurring near cancerous cells following NIR illumination [9]. Photothermal therapy is being developed for cancer treatment [94–96], whereby the illumination of plasmonic structures (generally gold nanoparticles) with NIR light causes localized heating. Using nanoparticles specifically targeted to cancer cells in conjunction with localized NIR illumination may enable selective ablation of cancerous tissue. Imaging QDs in the vicinity of the cells/tissue enables monitoring of the temperature as well as the spatial distribution of the heat—allowing researchers to elucidate appropriate treatment protocols that result in cancer cell death but minimize damage to surrounding cells. For example, in a study using gold nanostars (GNSts) as a probe for in vivo imaging and photothermal therapy, Liu et al. [96] characterized heating of the GNSts in vitro and temperature during heating was monitored using an infrared (IR) thermal imaging camera. Because calibration of IR thermal imagers can be quite complicated [97], further verification of temperatures using physical probes before and after heating was necessary. Using QD based thermometry may have simplified and improved their in vivo temperature measurements. The study by Bensalah et al. was performed in vitro, but recent developments of non-toxic, heavy metal free QDs provide a path towards in vivo studies.

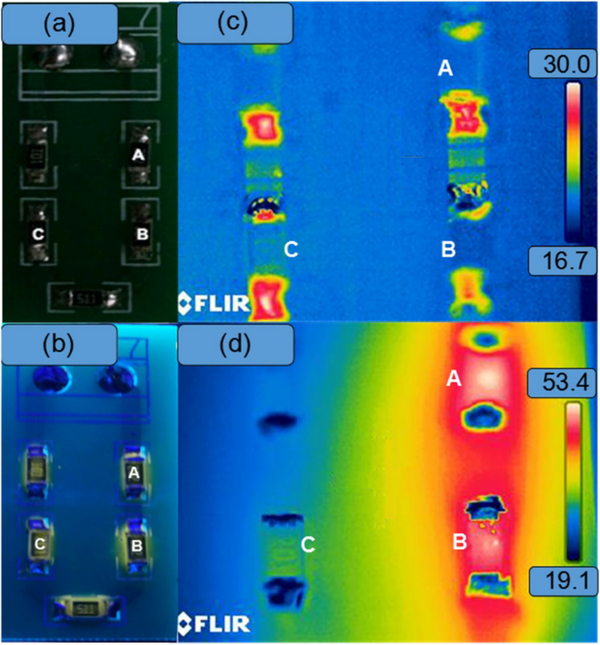

In 2014, Liu et al. used ZnCuInS/ZnSe/ZnS QDs to monitor temperature with spatial resolution on a circuit [12] (figure 6). The QDs exhibited the same behavior over three rounds of temperature cycling, indicating the reversibility and stability of the QD sensors. This is of particular note, because the use of cadmium-free QDs often results in a decrease in quality due to their synthesis methods being less well developed. In this study, a dropcast film of QDs was used to measure the surface temperature of resistors with different resistivity in a series of circuits by taking a fluorescence image. The difference in resistivities caused differences in surface temperatures at each resistor, resulting in different emission intensities of the QDs coating their surfaces (figure 6). Both millimeter- and micrometer-sized circuits were measured, showing the potential for using QDs as temperature sensors with micrometer resolution and low error (1.9%). This is of interest especially in the performance of micro- and nanoelectromechanical systems (MEMS/NEMS) and integrated circuits (ICs), where temperature often impacts performance. It is also a way to detect defects smaller than the resolution of thermocouples and thermal infrared imagers.

Figure 6:

(a) A circuit without and (b) with QDs under UV illumination. (c) Thermal infrared images of the circuits operating at 0 mA and (d) 7.9 mA. Resistor A, B, and C had resistances of 1982 Ω, 992 Ω and 196 Ω, resulting in different local surface temperatures during circuit operation. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [12]. Copyright 2014 Institute of Physics.

4.2. Ion Sensing with QD Quenching

Multiple groups have observed that QD PL can change significantly in the presence of ions, often rather specifically, making QDs themselves viable ion sensors [13, 16, 98–101]. In the typical case, such as the ion sensor described by Chen et al., QD emission is quenched in the presence of Cu2+, but unresponsive to other cations like Na+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ [13]. While the majority of the reports demonstrate the dose-dependent photophysical changes in the presence of free ions, few have followed up with experiments to elucidate the exact mechanism of these changes. In the case where ions adsorb to the surface of the QDs, QD emission can be enhanced by the ion passivating surface defects [14], or QD emission can decrease from the ion creating surface states that are effective pathways for non-radiative recombination, quenching the QD [15, 102]. Change in PL intensity, however, also changes with QD concentration, so sensors with a single wavelength readout can be prone to error if calibration is not done before every measurement.

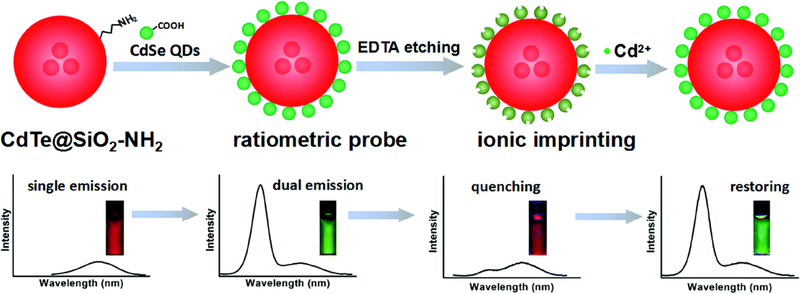

By using two QD emitters, this ion sensing mechanism can be incorporated into a more robust ratiometric ion sensing construct that is less prone to error due to changes in particle concentration. In one such design, large silica nanoparticles were used as a scaffold with red-emitting CdTe/CdS QDs protected within the interior and green-emitting CdTe/CdS QDs attached to the surface, thus exposed to the surrounding environment [15]. In the presence of Hg2+ ions, the green QDs on the surface were quenched, resulting in a change in the ratio of red and green emission intensities. By measuring the PL lifetime of the green surface QDs, the authors found that the lifetime decreased from 25.5 to 6.5 ns while the lifetime of the red QDs remained unchanged. The decrease in lifetime of the surface QDs indicated that the Hg2+ ions were adsorbed onto the surface of the green QDs, initiating charge transfer [102]. Further verification was done by taking absorption spectra of the QDs, showing a 10 nm red-shift of their first excitonic absorption peak. While quenching of the green QDs was seen in the presence of other divalent cations, none showed as significant a change in color as with Hg2+. However, a similar sensor design using CdTe QDs was found to also exhibit green emission quenching in the presence of gold nanoparticles [103], indicating a weakness in the sensor specificity. Wang et al. attempted to improve specificity by chemically etching the surface CdSe QDs with EDTA [16] (figure 7). Cadmium on the surface of the QD is chelated by EDTA and Cd2+ cavities are left on the surface. QDs exposed to EDTA exhibited a 5 nm blue shift in emission wavelength along with a decreased in emission intensity. In the presence of Cd2+ ions, the cavities on the surface of the QD are filled, resulting in a re-brightening of the QDs as well as a red-shift in wavelength. This chemical etching strategy had been previously applied for ion sensing [14, 17], but the two-color silica nanoprobe design allowed for a ratio-metric output. This sensor was, however, still not completely selective, as the presence of Zn2+ ions also increased the PL intensity of the exposed QDs. The authors did not note if the PL wavelength shift was different in the presence of Zn2+ or Cd2+ ions, a metric that might convey more information about the ions present.

Figure 7:

CdTe QDs emitting red are encapsulated in large silica nanoparticles which are then surface labelled with green emitting QDs. EDTA is used to etch the green QDs of their surface Cd2+ ions, resulting in quenching of green emission and overall red emission of the probe. The addition of Cd2+ ions fills the etched surfaces of the green QDs, resulting in a re-brightening of the surface QDs and change of the overall probe emission from red to green. Here, the red emission does not change because it is protected inside the silica nanoparticle and is used as a calibrator for the sensor as a whole. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [16]. Copyright 2016, Royal Society of Chemistry.

4.3. Intrinsic QD Photophysics for Voltage Sensing

QDs exhibit changes in their photoluminescent properties in response to an electric field due to the quantum-confined stark effect (QCSE). In QCSE, the presence of an electric field shifts the electron and hole wavefunctions along the field gradient, reducing the overlap integral between them [104]. This leads to an increased PL lifetime, red-shifting of the emission peak, and a decrease in the overall emission intensity [105].

The QCSE was demonstrated in quantum wells [104, 106, 107] before Ekimov et al. demonstrated the effect in quantum dots. Using glass-embedded CdS and CdSe QDs, the authors showed a 10 meV redshift in the absorption edges of the QDs while applying electric fields up to 100 kV/cm [108]. To verify QCSE in quantum dots, Empedocles and Bawendi used single QD spectroscopy, eliminating the inhomogeneous broadening of emission spectra that often characterizes ensemble measurements [109]. To accomplish this, they deposited CdSe or CdSe/ZnS QDs of various sizes (4.4 nm to 7.5 nm) onto patterned electrodes and acquired single particle spectra with a far-field epifluorescence microscope cooled to 10 K. With this setup, the authors showed emission shifts as large as 75 meV after applying electric fields of 350 kV/cm. Other groups extended these low temperature single-QD spectroscopy results, showing red-shifting as well as the expected decrease in photoluminescence intensity with increasing electric fields for type I QDs [110] and type-II quantum rods [111].

Harnessing the QCSE for sensing electric fields in practical applications (such as an action potential in neurology) requires that a sizable change in PL peak position or intensity occurs at room temperature or higher. Noting that different geometries, compositions, and band alignment structures can all effect QCSE, Park et al. screened the single-QD change in emission for eight nanoparticle types in the presence of an electric field [112]. These nanoparticles included two homogeneous type I quantum rods of varying lengths, two quasi-type II quantum rods of different lengths, two type II QDs, and two asymmetric heterostructures. This systematic study allowed the authors to tease apart several variables, uncovering several interesting results. First, for homogeneous type I quantum rods, increasing the length did not change the average shift in the electric field, indicating that there was incomplete charge separation along the rod. Second, rod shaped geometry showed greater shifts in an electric field than symmetric core/shell geometry, consistent with previous reports [111]. Finally, they demonstrated that type II asymmetric rods exhibited the most significant response, with some individual particles exhibiting a roughly linear response to the electric field culminating in a 13 nm red-shift in the emission peak and 36% drop in PL intensity in response to a 400 kV/cm field.

These results encouraged others to assess the ability of QDs to respond to physiologically relevant electric field strengths (~100 kV/cm). Marshall and Schnitzer used numerical finite basis methods to model spherical QDs and the tunneling resonance method to model heterostructured quantum rods, and calculated the response of each to the electric field changes induced by a typical action potential [113]. They found that type II and quasi-type II heterostructures exhibit greater voltage sensitivity than spherical geometries, consistent with the results above from Park et al. They calculated that CdTe/ZnTe quantum rods would produce a five-fold greater percent change in PL lifetime (Δτr/τr) than CdTe/ZnS core-shell structures. However, this enhancement is highly sensitive to the minimal valence band offset between the two materials; similar heterostructures with a larger offset (such as CdTe/CdSe) showed less responsiveness to voltage due to having less polarizable holes. It is also worth noting that these simulations are contingent upon perfect orientation of the quantum rods perpendicular to the electric field.

Using signal detection theory, Marshall and Schnitzer also assessed the feasibility of using the QCSE in QDs to detect single spikes in neurons compared to voltage-sensitive dyes (VSDs) and genetically encoded voltage indicators (GEVIs). They showed that even type I spherical CdTe QDs in the cell membrane would outperform contemporary VSDs and GEVIs in detecting action potential spikes, even at concentrations orders of magnitude lower than VSDs and GEVIs. These modeling results, however, were based on comparisons to a GEVI (i.e., ArcLight) and VSD (i.e., hVOS) that are now outdated compared to the current best-in-class GEVIs and VSD.

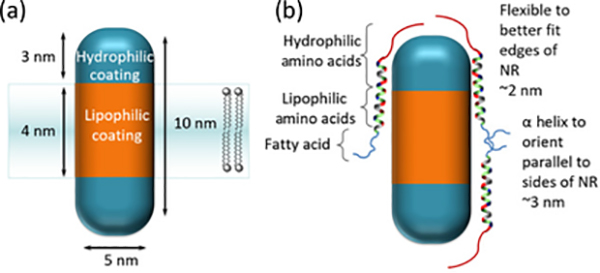

A recent report by the Weiss group was the first to harness QCSE in quantum rod heterostructures in vitro in HEK293 cells [18]. They designed quasi-type II CdSe-seeded CdS rods with hydrophobic and hydrophilic peptide coatings to align the rod perpendicular to the electric field (figure 8). This novel attempt to orient rods in the membrane and measure voltage yielded interesting, but somewhat disappointing, results. The quantum rods were able to respond to the electric discharge of HEK cells, but were nearly an order of magnitude less sensitive than ANEPPS (a common VSD), and exhibited significantly noisier signals. The authors point to the challenge of inserting the rods perpendicular in the field: only 16% of their rods were oriented properly, indicating the challenge of controlling rod insertion into the cell membrane.

Figure 8:

CdSe seeded CdS nanorods (NR) for in vitro voltage sensing of cells. Peptides with hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions are used to coat the nanorods in order to align them perpendicularly to the electric field. In the presence of the electric field, the quantum confined Stark effect (QCSE) causes a peak red-shift and reduction in PL intensity. Adapted from Ref. [18] Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commerical License 4.0(CC BY-NC)

4.3. Dual-Color Intrinsic Quantum Dot Sensors

Changes of PL intensity alone can be a poor sensor output as other events, such as a change in QD concentration, particle aggregation, or other changes in the environment, may also result in a change in emission intensity. Ratiometric measurements that monitor the change of the ratio of PL intensity at two different wavelengths are generally preferred to single color measurements because they are less sensitive to environmental factors. Dual color sensors can exhibit uncoupled or coupled emission, whereby the second color acts either as a constant emitter for normalization of the variable emission or exhibits variable emission with inversely proportional changes in emission intensity to the first emitter, respectively. In the former case, the consistent emission intensity of the secondary color is used as a control in the system, whereas in the latter case, the secondary color intensity enhances the effective change in signal in response to the stimulus. In this section, dual emitting quantum dots and their use as sensors is briefly discussed. Several other dual-color sensors operating on the principle of energy transfer will be covered in sections 5 and 6.

4.3.1. Dual Emitting Quantum Dots

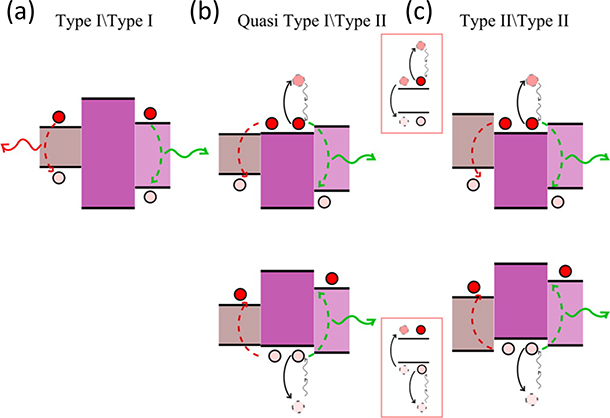

The creation of a single nanoparticle that exhibits two emission colors is interesting from both a fundamental and applications perspective. Synthesis of QD-dual emitters is achieved by: 1) growing core/shell/shell QDs with materials that result in a quantum dot-quantum well (QD-QW) band alignment, 2) growing seeded quantum rods (QRs) tipped with a second material, or 3) including dopants during nucleation or growth. Quantum dots that fall in the first two categories are dubbed double quantum dots and exhibit unique optoelectronic properties including intraparticle charge transfer, and luminescence upconversion [114]. Core/shell/shell heterostructures that result in dual emission are shown in figure 9.

Figure 9:

Bandgap alignments that result in dual emission for double quantum dots. (a) Type I\Type I emitters contain two electron hole pairs spatially and energetically separated by a wide bandgap barrier resulting in simultaneous dual emission. (b) Quasi Type I\Type II and (c) Type II\Type II alignments result in a double well for either the electron or hole. One of the charge carrier pairs is non-radiatively lost through Auger processes and the emission color switches stochastically as a result. Reproduced from Ref. [114], published under an ACS AuthorChoice License. DOI: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00554

Type I\Type I emitters consist of an energy barrier sandwiched between the core and outer shell. For example, several examples of CdSe/ZnS/CdSe dual emitters have been reported [115–118]. In Quasi-Type I\Type II dual emitters like the CdSe/CdS/ZnSe heterostructure [119], the nominal energy offsets in either the conduction or valance band create a double well for either the excited electron or hole charge carrier, respectively. Since the probability of emission of more than one photon is low due to the likelihood of non-radiative Auger recombination, the emitted photons stochastically switch between the two possible emission colors. Type II\Type II emitters work similarly and include PbS/zbCdSe/wzCdSe/CdS [120] heterostructures, where the difference in crystal structure of the same material results in a bandgap offset at the core/shell interface. Similarly, Zhao et al. [121] synthesized PbS cores with a cation-exchanged zinc-blende (zb) CdS shell before depositing a thick (wz) wurtzite CdS layer on top. The zb CdS shell served as a potential barrier between the PbS core and wz CdS shell, resulting in red emission from the core and bue emission from the shell.

So far, double dots have generated interest as optical gain media [115] and upconversion platforms [120], but the dual emission can also be used for sensing. For example, the PbS/CdS QDs described above were embedded in poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) films to measure PL temperature dependence [122]. Emission from both the core and shell increased as temperature decreased. Unsurprisingly, the temperature dependence was not the same between the different materials, resulting in a change in the ratio of blue and red emission.

Another example of a dual color intrinsic sensor was demonstrated by Razgoniaeva et al. [123]. A double well PbS/CdS/CdSe heterostructure was synthesized that exhibited emission from the PbS core as well as from the CdSe outer shell. The authors then investigated how the presence of methyl viologen (MV2+) and 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) changed the PL emission profile of the QDs. MV2+ quenched PbS emission much more efficiently than CdSe emission as a result of the long PbS PL lifetime when compared to CdSe. The longer PbS fluorescence lifetime results in slower non-radiative processes that allow for quenching at a higher rate. In the presence of MPA, CdSe emission was more efficiency quenched, indicating that the rate of hole transfer from CdSe to MPA is much higher than that of PbS to MPA. For both analytes, one color is quenched more efficiently than the other, so the ratio of emission colors can be used to quantify analyte concentration.

While both of the dual-emitting QD sensors described here have limited long-term application potential because they contain multiple toxic constituents (Pb and Cd), the idea of using a barrier between the core and shell of a QD to create dual emission for use as a temperature sensor could also be explored with more environmentally friendly compositions currently being developed.

4.3.2. Doped QDs for Dual-Color Sensors

Doped QDs provide the opportunity to develop QD-based temperature sensors with ratiometric fluorescent readouts. The presence of dopants in a QD introduces additional energy levels, and, depending on where the dopant levels lie relative to the valance and conduction bands of the QD, some structures exhibit dual emission from a single QD. If the ratio of fluorescence intensity between the two peaks is temperature sensitive, ratiometric calibration of peak intensities with regard to temperature is possible.

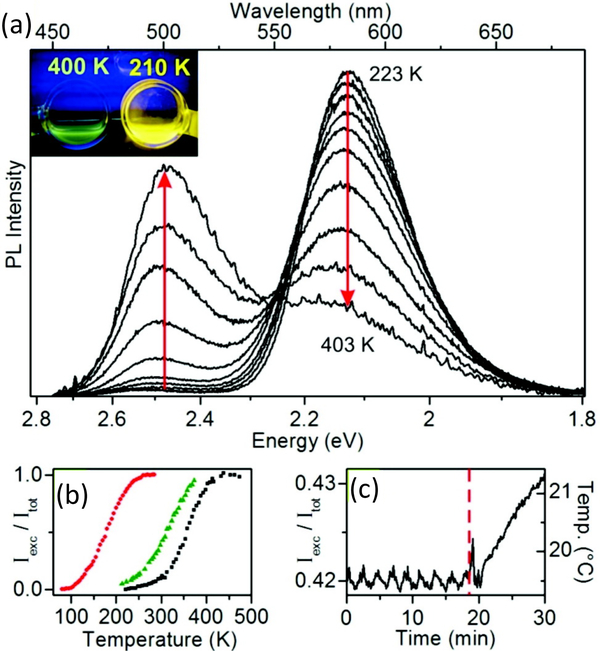

An excellent example of this was demonstrated when Vlaskin et al. developed Zn1-xMnxSe/ZnCdSe QDs with dual emission [124]. Dopant loading in the core was controlled and the QD bandgap was tuned relative to the dopant levels by changing shell thickness. Their QDs showed a large change in the ratio of exciton versus dopant emission when temperature was varied (figure 10(a)); in addition, the temperature range for sensing could be tuned by changing the dimensions of the core and shell. To demonstrate this, three QDs with differing core/shell dimensions were synthesized that showed temperature dependent color change across a temperature range of 100 – 400 K (figure 10(b)). Their measurements were repeatable through three temperature cycles. To further highlight the advantage of ratiometric sensing, they transferred their QDs from toluene to heptane, decreasing overall QY by ~50%. While the overall intensity of the QD decreased as a result, the ratio of the two emission colors was identical.

Figure 10:

Fluorescence change as a function of temperature for Zn1-xMnxSe/ZnCdSe QDs. A) The ratio of exciton emission and dopant emission changes as a function of temperature. Inset: picture showing visible color differences at two temperatures. B) Temperature response curves for three QDs with different core/shell dimensions demonstrate the tunability of the QD heterostructure design for temperature sensing in different temperature regimes. C) PL of a QD sensor cooled to 19°C. The red dotted line indicates the removal of the coolant. The sensor subsequently warmed, resulting in an increase in the ratio. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [124], Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society.

Other dual emission QDs used in nanothermometry include Mn-doped CdSSe/ZnS core/shell QDs [19], ZnMnSe/ZnS/CdS/ZnS QDs [125], and alloyed ZnCdMnSe QDs [126]. Ag- and Mn- co-doped [20] or Cu- and Mn- co-doped ZnInS QDs are a more recent examples that extend this premise to heavy metal-free compositions [127].

5. QDs in Förster Resonance Energy Transfer

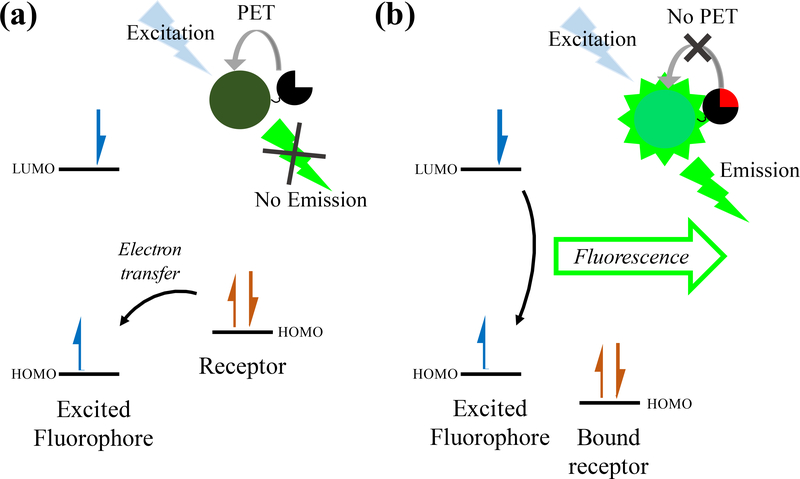

The sensors discussed above exhibit a change in PL intensity due to a change in QD concentration or an environmental force altering the QD photophysics. Arguably the most common sensing mechanisms, however, involve energy transfer mechanisms to another molecule. Several energy transfer mechanisms exist and can be classified generally into two categories: resonance energy transfer (RET) or electron transfer (eT). An exceptionally comprehensive review on energy transfer involving QDs has been recently published [26]. Here we will more succinctly highlight energy transfer mechanisms and applications in sensing.

The most prominent energy transfer mechanism in biosensing is Förster, or fluorescence, resonance energy transfer (FRET), a distance-dependent non-radiative energy transfer from a donor to acceptor chromophore through dipole-dipole resonance. Because FRET uses two chromophores, ratiometric sensing is often built in, with the exception of systems where the acceptor chromophore is non-fluorescent (i.e., a quencher). As previously discussed, ratiometric sensing is often advantageous to single color sensing for internal calibration and enhanced sensitivity. In FRET sensors, one can monitor both the efficiency of energy transfer from the donor to the acceptor as well as the resulting changes in the acceptor-donor emission ratio. Factors affecting FRET efficiency include 1) the donor-acceptor separation distance, 2) the spectral overlap between the acceptor and donor, 3) the quantum yield of the donor, and 4) the alignment of the donor and acceptor dipoles. The ratiometric measurement is furthermore impacted by the quantum yield of the acceptor molecule and analysis can be complicated by overlap between the donor and acceptor emission peaks. For energy transfer to occur, acceptor absorption must overlap with the donor emission wavelengths. The degree of this overlap is defined as the spectral overlap integral, Jλ [31, 128]:

| Eqn. 3 |

| Eqn. 3a |

where fD(λ) is the fluorescence spectrum of the donor (which is normalized to 1 by dividing by its total area, Eqn. 3a), and εA(λ) is the molar absorptivity of the acceptor, all scaled to wavelength, λ; Jλ has units of M−1 cm−1 nm4. To compare the expected performance of potential donor-acceptor pairs, one uses the overlap integral to calculate the Förster distance, R0 i.e., the donor-acceptor distance at which 50% FRET efficiency is observed [31],

| Eqn. 4 |

where κ2 is the dipole orientation factor between the donor and acceptor, ΦD is the quantum yield of the donor, and n is the solvent refractive index (all unitless terms). The dipole orientation factor κ2 can span from 0 to 4, with a value of 0 for no overlap in the dipoles and 4 for perfectly aligned dipoles. In FRET sensors where the chromophore dipoles are randomly oriented over time, κ 2 = 2/3 is used. The units used to calculate R0 can differ, so the expression that uses spectral overlap integrated over wavelength is also shown in order to avoid confusion in choice of units. If R0 is known, the FRET efficiency of a system at a specific donor-acceptor separation, rDA, can be calculated [31]:

| Eqn. 5 |

Experimentally, FRET efficiency can be monitored through change in donor fluorescence intensity or fluorescence lifetime [31]:

| Eqn. 6 |

Where FDA (τDA) is the fluorescence intensity (lifetime) of the donor in the presence of an acceptor, and FD (τD) is the fluorescence intensity (lifetime) of the donor in the absence of energy transfer. By experimentally monitoring the fluorescence of a FRET system, one can use the changes in PL intensity or lifetime to determine the FRET efficiency and thus donor-acceptor distance or use knowledge of the sensor configuration (donor-acceptor distance) to predict the sensor FRET efficiency.

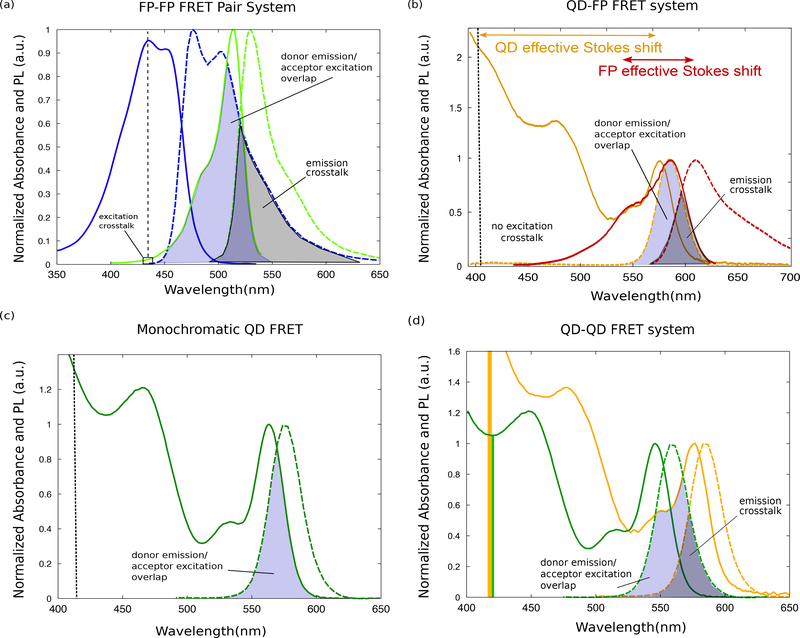

While FRET can occur between any two chromophores, there are a few advantages of using QDs as FRET donors. In addition to the overarching theme of QD PL being brighter and more photostable than dyes, the unique spectral profile of QD FRET donors can be used to reduce crosstalk. Due to the shorter effective Stokes shift of most organic emitters (including fluorescent proteins), challenges arise with maximizing spectral overlap for high FRET efficiency while minimizing excitation and emission crosstalk. If an excitation wavelength is chosen to minimize excitation crosstalk such that only the donor dye or protein is excited, the overall brightness of the system is decreased, if it requires that the donor is excited away from its absorption maximum. In contrast, QDs have broad absorption in the UV with increasing molar extinction coefficients at higher energies, i.e., in the UV and blue wavelength range. In this context, photoexcitation far from the QD emission peak (and the acceptor absorbance) leads to enhanced absorption by the QD, creating a brighter system. Figure 11 illustrates the differences in spectral overlap between various donor-acceptor systems [38].

Figure 11:

The absorption and emission spectra for (a) a pair of fluorescent proteins (FP-FP) and (b) a QD-FP FRET pair. Excitation crosstalk is avoided in the FP-FP case by choosing FPs with suboptimal spectral overlap, whereas the large Stokes shift of the QD allows for zero excitation crosstalk in a QD-FP pair and perfect overlap of the donor emission and acceptor excitation. In panel (b) the FP effective stokes shift when exciting away from its excitation maximum is indicated. While exciting away from the FP excitation maximum can decrease crosstalk, sensor brightness will suffer. Panels a and b are also representative of FRET pairs using fluorescent dyes. (c) Spectral overlap in the QD absorption and emission spectra can lead to homo-FRET. (d) Two color QD-QD FRET results in significant direct excitation of the acceptor. Adapted from Ref. [38], Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commerical License 4.0 (CC BY-NC)

5.1. FRET Sensors Using QD Donors

As with the fluorescently labeled QD sensors described in the first section, FRET sensors using QDs benefit from the large surface area that provides a base for a multitude of functionalization schemes. This is well demonstrated in an early report for Suzuki et al. [129]. They functionalize the surface of commercially available QDs with ssDNA, dsDNA, fluorescein-5, and GFP to make DNase, DNA polymerization, pH and proteolytic FRET sensors respectively. The authors also highlight that using QDs as FRET donors provides a pathway for single excitation wavelength multiplexing and show that by mixing their nuclease and protease sensors they can monitor both sensing events simultaneously as long as QDs of different and distinguishable emission wavelengths are used for each. While the discussion of these sensors is largely qualitative, the possible breadth of applications for QD-FRET based sensing was effectively demonstrated.

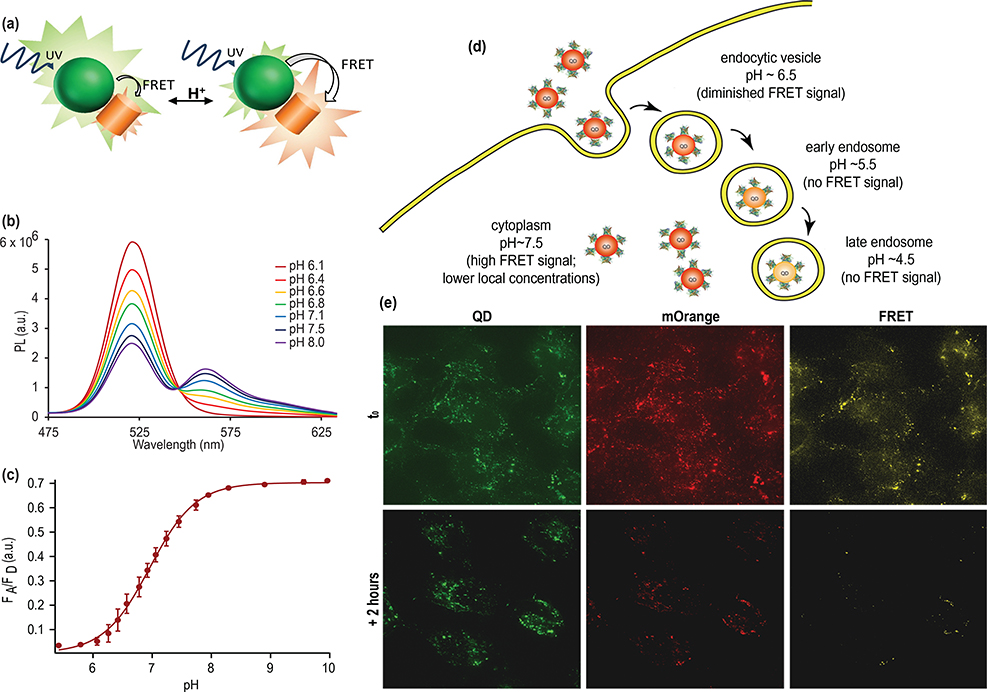

One way to use FRET for sensing is to utilize changes in the optical properties of the acceptor molecule to generate a responsive change in FRET efficiency through changes in the spectral overlap. There are a couple of examples of this mechanism in pH sensing based on the organic fluorophores squarine [130] or SNARF [131] or variants of the fluorescent protein mOrange [132]. In the case of the QD-mOrange pair, the absorption cross-section of the FP varied significantly with pH, changing the FRET efficiency, resulting in a 20-fold difference in the ratio of the acceptor emission intensity to the donor acceptor intensity over a physiologically relevant pH range (pH 6–8) (figure 12). Similarly, the absorption of 2D materials such as molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) change in the presence of an electric field, and can be used as FRET acceptors in devices that can sense changes in applied field [133].

Figure 12:

QD-FRET based pH sensor for intracellular imaging. (a) Schematic of ratiometric pH sensor based on change in absorption cross-section of acceptor fluorescent protein mOrange in response to pH. At alkaline pH, mOrange is optically active and acts like an efficient FRET acceptor, siphoning energy from the QD donor. At acidic pH, the mOrange is not optically active and FRET is diminished, resulting in higher emission intensity from the QD. (b) Change in PL emission upon titration of the FRET sensor. The donor QD emission is highest with little FRET evident at pH 6.1. At more alkaline pHs, energy transfer results in a decrease in QD donor emission intensity and increase in mOrange acceptor emission intensity. (c) Plot of the acceptor emission intensity to donor emission intensity versus pH creates a calibration curve for the ratiometric sensor. (d) Schematic of how changes in energy transfer efficiency results in changes in emission color as the fluorescent probe progresses through the endocytotic pathway. (e) After brief exposure to cells (t0) FRET is evident in epifluorescence microscopy. After 2 hours, endocytosed probes are exposed to a more acidic environment and exhibit substantially reduced FRET. Adapted with permission from Ref. [132], Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society.

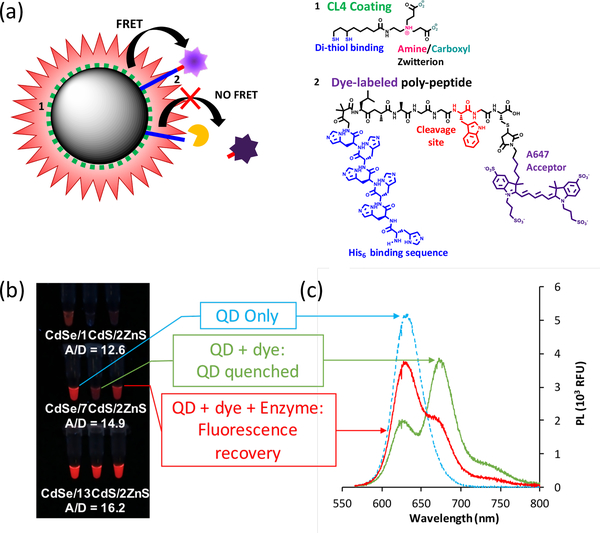

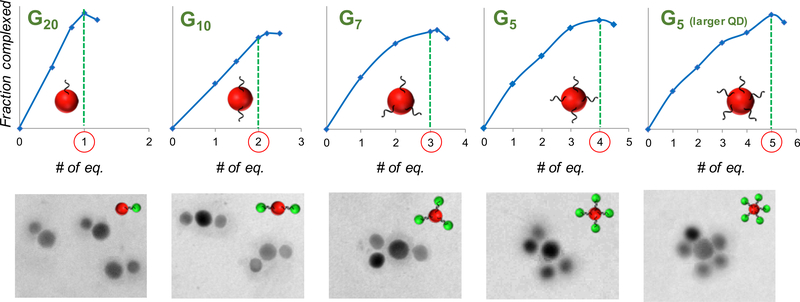

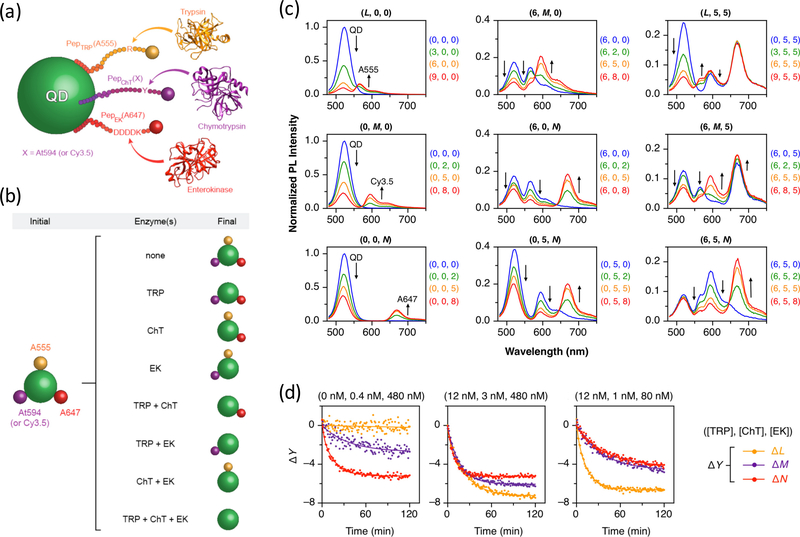

Probably the most frequently used FRET designs sense a change in distance between the donor and acceptor pair, rDA. FRET efficiency is highly distance dependent (eqn. 5) and therefore changes in rDA on the nanometer scale can be monitored. Because FRET efficiency is negatively impacted by increased sensor size, the size of the fluorophores used is a parameter of interest when designing a FRET probe. Towards that end, the Dennis group performed a systematic study comparing CdSe/xCdS/2ZnS QD donors of varying shell thicknesses with dye-labeled, tryptophan cleavable, his-tagged peptides self-assembled to their surface [25]. By using the same acceptor for every QD, the effect of shell thickness and size on FRET efficiency, and its implications on sensor design were explored. As expected, by using QDs with thicker shells and increased overall size, the maximum FRET efficiency of the probe decreased. However, it was shown that the larger QD size significantly increased brightness, with the brightest samples being almost 8-fold brighter than commercially available QDs emitting at similar wavelengths. As previously discussed, increased fluorophore brightness can be useful for POC applications where cost and ease of detection are a concern. While all sensors were able to detect the presence of tryptophan when using a fluorimeter for measuring fluorescence, only the sensor using a medium sized QD (diameter ~ 9 nm) was able to show visible changes in fluorescence after the addition of tryptophan, as it was both bright enough for facile visual detection and still small enough for efficient energy transfer (figure 13) [25].

Figure 13:

In a typical enzyme cleavage assay, his-tagged, dye-labeled peptides are self-assembled to the QD donor, quenching QD emission via FRET. In the presence of enzyme, the peptide is cleaved, terminating FRET efficiency and resulting in re-brightening of the QD emission. (a) shows a schematic of FRET based enzyme sensing and panel (b) shows images of sensors using QDs of different sizes as donors. Only the medium sized donor shows visible changes in brightness after addition of enzyme, while all sensors can be monitored by taking PL using a fluorimeter (c). Adapted from Ref. [25] with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.

rDA of a pre-assembled construct can change when the sensor experiences conformation change or complete dissociation or displacement of the acceptor from the donor. The sensor described above uses an enzyme cleavable peptide to mediate acceptor displacement in the presence of analyte of interest. QD-FRET has been widely demonstrated for enzyme sensing [23, 25, 28, 34, 134–138]. Proteolytic activity can be monitored by attaching acceptors to quantum dot donors with an enzyme cleavable peptide. Frequently, dye-labeled peptides containing a histidine region and enzyme cleavable sequence are self-assembled to QDs as FRET acceptors, quenching the PL of the QDs [23, 25, 28, 34, 135, 136]. In the presence of enzyme, the peptide is cleaved releasing the acceptor from the QD and reducing FRET, as observed through the enhancement in QD PL intensity [135]. Changes in the PL over time can be used to calculate kinetic parameters of substrate digestion through Michaelis-Menten (MM) kinetic formalism. Similarly, fluorescent proteins (FPs) can be engineered to include enzyme cleavable linkers to achieve the same effect [134]. In 2012, Algar et al. performed a more detailed study tracking the number of peptides per QD over time and showed that substrate digestion deviates from predicted MM formalism. A hopping mode of activity was described, whereby the enzyme consumes multiple substrates on a QD surface before relocating to a new QD, causing an initial enhancement in the rate of digestion [136]. Diaz et al. [137] explored this further by creating QD-dye proteolytic FRET sensors for both elastase and collagenase. They found that elastase was well represented by the MM model whereas collagenase was not, demonstrating that while QD-dye FRET protease sensors can be used for enzyme detection, the kinetics of these reactions can be variable.

Acceptor displacement can occur through processes other than enzyme cleavage—for example, QD FRET-based immunoassays [139, 140]. These have similar design aspects to QD FLISAs, but the QD is used as both a platform and FRET donor. In this scheme, the sensor does not need to be attached to a substrate but is instead measured directly in solution. This is advantageous in that is does not require long incubation times or multiple washing steps. For example, Kattke et al. optimized a QD-FRET system for the detection of Aspergillus mold spores even in a solution with high background autofluorescence [140]. A QD donor was conjugated to IgG antibodies and incubated with quencher-labeled analytes, resulting in a FRET-based decrease of QD PL. The presence of the target analyte displaced the quencher-labeled analyte, resulting in QD fluorescence recovery.

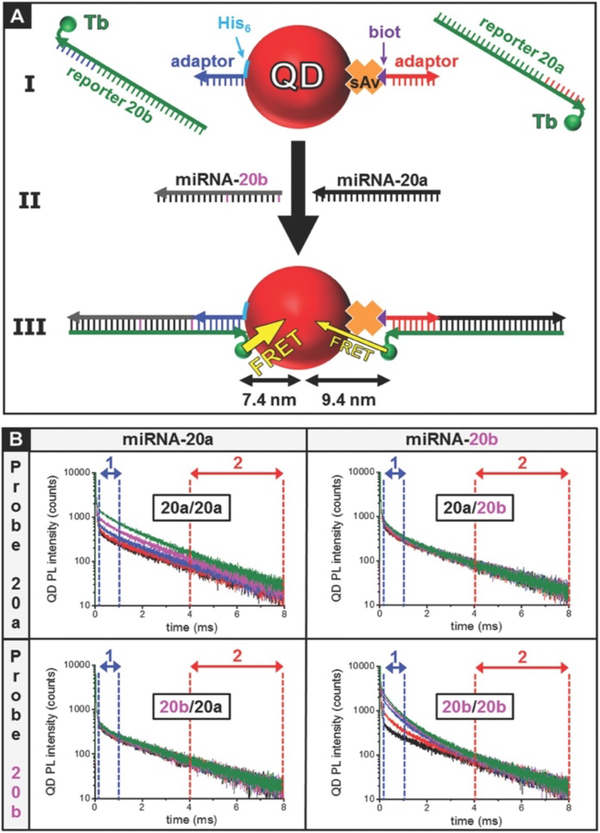

5.3. FRET Sensors Using QD Acceptors

As already exemplified in this review, QDs are generally used as FRET donors due to their bright emission and broad absorption. According to the Förster formalism, non-radiative energy is transferred from an excited donor molecule to an acceptor molecule in its ground state when they are in close enough proximity. The broad excitation profile and relatively long PL decay times for QDs compared to traditional fluorescent dyes (τQDs ~ 5 – 100 ns vs. τdyes ~ 1 – 5 ns) hinders the use of QDs as FRET acceptors. Upon photoexcitation, both the dyes and QDs are excited, with the QD remaining in an excited state than much longer the dye, precluding energy transfer [141–143]. The introduction of luminescent lanthanides as FRET donors with up to millisecond lifetimes change this dynamic by utilizing a FRET donor with a PL lifetime much longer than that of the QD acceptor [35, 36]. By collecting PL lifetimes in time gates much longer than the natural decay of the QD, but still within the lifetime of the lanthanide decay, the direct excitation of the QD and any background auto-fluorescence will not be recorded, greatly simplifying analysis of the system.

Lanthanide emitters can be incorporated into FRET devices in the form of molecular complexes or lanthanide-doped upconverting nanoparticles. Time-resolved spectroscopy is used to record the luminescence intensities of FRET-pairs in individual detection channels in time-gated mode after pulsed excitation. If the lifetime of the acceptor is much shorter than the lifetime of the donor, the lifetime of the donor in the presence of acceptor can be assumed to be the same as the lifetime of the acceptor in the presence of the donor (τDA = τAD for τA << τD). Time-gated detection of fluorophores with long luminescence lifetimes efficiently suppresses interference from biological auto-fluorescence as well as directly excited FRET-acceptors [29, 143]. Therefore, a ratiometric output for biological assays can be used to quantify the biomolecule of interest while also suppressing sample and excitation source fluctuations [35, 144]. The sensor output is the ratio of the time-gated photoluminescence intensities of the FRET acceptor and FRET donor, in the presence of the donor and acceptor, respectively, over a defined time period:

| Eqn. 7 |

where is the time gated PL intensity of the acceptor detection channel integrated over a time-window from t1 to t2 (μs or ms) measured at its emission wavelength, and is the time-gated PL intensity of the donor detection channel over a time-window from t1 to t2 (μs or ms) measured at its emission wavelength.

In 2005, Hildebrandt et al. showed that QDs could be used as efficient FRET acceptors when paired with a terbium chelate with a long-lived emission lifetime in the ms range [145]. For this purpose, they designed a time-resolved FRET system based on biotin-streptavidin interaction where CdSe/ZnS QDs with an emission maximum at 655 nm were coated with a biotinylated polymer complex (QD655-biot) and streptavidin was labelled to the terbium chelate through its activated ester group (strep-Tb). Using a fixed concentration of strep-Tb and increasing concentration of QD655-biot, they measured the time-resolved emission of the donor and acceptor following pulsed excitation at 308 nm. The FRET ratio from this system integrated from 0.25 – 1 ms was dependent on the QD655-biot concentration, strongly suggesting sensitized emission of the QDs in the μs range due to FRET. The analysis of the QD emission decay curve after FRET also revealed the appearance of two new long-lived components arising from strep-Tb. The Tb-to-QD FRET system resulted in improved sensitivity of biotin detection with a picomolar detection limit [145].

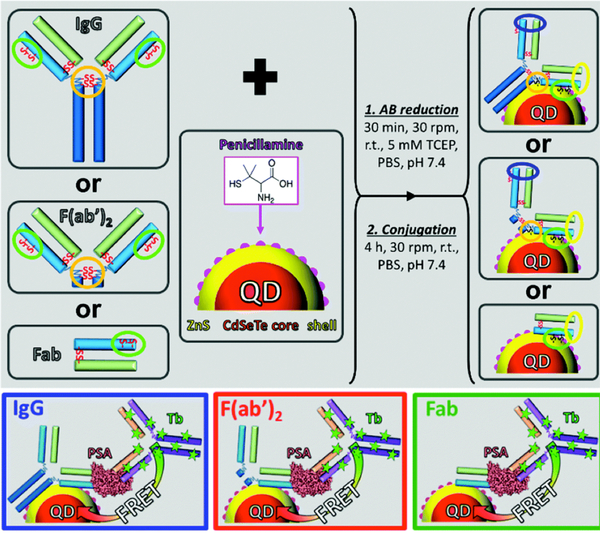

Since then, clinically relevant biomarker detection has been demonstrated using time-gated Tb-to-QD FRET in homogeneous bioassays. When using antibodies in FRET based sensors, their large size limits maximum achievable FRET efficiency. Because FRET is highly distance dependent, the FRET efficiencies of QD donor-based immunoassays tend to be low. One route towards alleviating this issue it to use antibody binding fragments instead. Wegner et al. bioconjugated commercially available QDs from eBioscience (eQDs) and a carbodiimide-functionalized terbium complex (Lumi4-Tb-NHS; L4Tb) from Lumiphore with two distinct monoclonal antibodies (IgG), divalent fragments (F(ab’)2), or monovalent antibody fragments (Fab) against prostate specific antigen (PSA) [146]. In the presence of PSA, the QD-antibody (fragment) and L4Tb-antibody (fragment) both bind to the analyte, bringing them in close proximity for FRET. They found that using QD-Fab bioconjugated yielded the highest sensitivity in the QD-Tb FRET system due to the smaller biomolecular size reducing the donor-acceptor distance and a higher labelling ratio. The limit of detection (LOD) of 1.6 ng/mL PSA in serum samples is significantly lower than the clinical cut-off of PSA of 4 ng/mL [146]. In a subsequent study, the flexibility of the FRET system was demonstrated using nanobody-eQD650/L4Tb conjugates for the detection of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in low volume buffer and serum samples with LODs of 23 ng/mL and 34 ng/mL, respectively, which are below the recommended clinical cut-off level of 45 ng/mL [147].

Iterations on the Tb-QD FRET immunoassays helpfully demonstrate the challenges of conjugating complex biomolecules like antibodies to QDs in a way that maintains high binding affinity for the analyte, and quantification of improvements that can be gained by using different QD coatings or smaller antibody fragments. Since eBioscience QDs have been discontinued, Bhuckory et al. developed a standard and simple procedure to conjugate thick PEG-coated QDs from Life Technologies (iQDs) to antibodies and tested their efficacy in a L4Tb-to-QD FRET immunoassay for PSA using Fab and IgG [148]. Disulfide bonds on Fab were reduced to thiols and conjugation to iQD605/655/705 was performed by transferring amine reactive QDs to maleimide-reactive QDs using sulfo-EMCS as a crosslinker. Their results showed a significant increase of the FRET-ratio with increasing concentration of PSA for all three FRET systems. The strongest relative increase in FRET-ratio was observed for the L4Tb-iQD705 FRET pair due to the most efficient FRET with the least L4Tb background, due to its large Förster distance. The three FRET systems exhibited sub-nanomolar LODs of 23 ng/mL, 3.7 ng/mL and 2 ng/mL for L4Tb-iQD605, 655, and 705, respectively [148].

In 2016, Mattera et al. [149] further reduced the size of their biosensor. In their study, they conjugated Fabs to QDs for FRET-based sensing comparing commercially available water-soluble QDs coated with a polymer to the same base QDs coated with a compact, commercially available zwitterion, penicillamine. Two colors of QDs, emitting at 605 and 705 nm, coated with the polymer or with penacillamine were functionalized with Fabs and analyzed for performance in a FRET assay. Sensors utilizing the penicillamine-coated QDs were 6.2-fold and 2.5-fold more sensitive than the 605 nm and 705 nm polymer-coated QDs, respectively. This was attributed to the decrease in overall size of the QD/Fabs when using penicillamine and coincided well with other studies showing that the FRET efficiency between CdSe/ZnS QDs and his-tagged FPs is highly dependent on the ligand used for water solubilization [150, 151]. Other reports of small molecule ligands for water-solubilization have been published [152–154], but none have demonstrated stability over as extended of a time period (2 years) as Mattera et al. [149]. In a later study, Bhuckory et al. [155] used the compact QDs as demonstrated by Mattera et al. [149], to further improve the sensitivity of their immunoassay for PSA detection. IgGs and Fabs against PSA via their endogenous thiols within the antibodies (fragments) were directly conjugated to the surface of the Zn-rich QD surface (figure 14). This new and simple conjugation strategy allowed for an even more compact biosensor which allowed better LODs with 0.21 ng/mL for QDs conjugated to IgGs and 0.08 ng/mL for QDs conjugated to Fabs. As a comparison, the LOD for this QD-Fab was 10 and 25 times lower compared to conjugation via maleimide-terminated ligands [149] and polymer-coated QDs [148], respectively.

Figure 14:

(top) Direct conjugation of thiol-antibody (fragments) to the surface of compact QDs via metal affinity of thiol to Zn. (bottom) When the antigen PSA is introduced in the system, both the QD-antibody (fragment) and L4Tb-IgG bind PSA, bringing the L4Tb and QD into close proximity, resulting in FRET. Adapted from Ref. [155] with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.

The work of Qiu et al. demonstrated the necessity of careful QD-antibody conjugation optimization when taking into account antibody size, orientation, conjugation ratio and biological crosstalk on the performance of single and duplexed immunoassays [156]. By using different types of antibodies and orientations of nanobodies against EGFR and HER2, they obtained many combinations of QD-antibody/QD-nanobody + L4Tb-antibody/L4Tb-nanobody and tested each in a FRET immunoassay. Their findings showed that for a single assay, the highest sensitivity of EGFR was achieved using full-sized antibodies of cetuximab conjugated to L4Tb and matuzumab F(ab) on eQD650, yielding an LOD of 2.9 ng/mL. An LOD of 8.0 ng/mL was determined for HER2 detection when using oriented nanobodies conjugated via their terminal cysteine to L4Tb and eQD605. As compared to using dyes for multiplexing [157], their duplexed immunoassay showed specific and sensitive detection of EGFR and HER2 from a single sample at low nanomolar concentrations without requiring complex spectral or biological correction [156]. In this same perspective of improving QD-based immunoassays, Annio et al. showed the importance of antibody-to-QD ratio in an FRET assay performance. They observed an 8-fold enhancement in LOD and 5-fold in the dynamic range of their FRET assay when increasing the number of IgG antibodies against total prostate specific antigen (TPSA) on the surface of QDs [22].

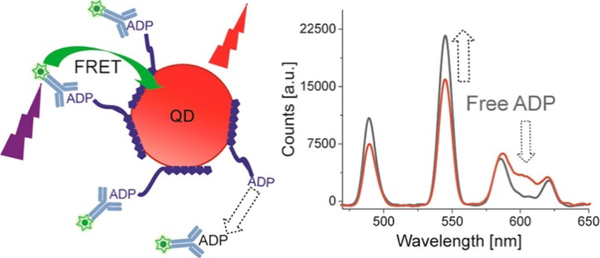

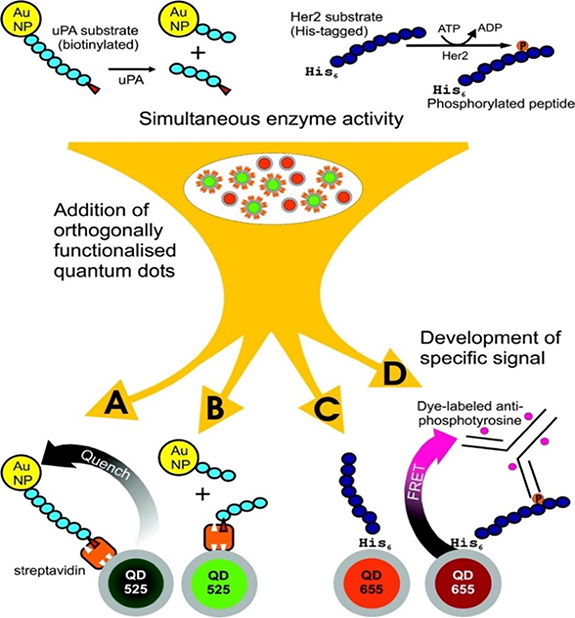

Díaz et al. took advantage of the lanthanide-QD FRET system for kinetic studies by designing the first broad nanoparticle based time-resolved FRET assay for adenosine diphosphate (ADP) [21]. In their sensor, QDs were labelled with a His6-ADP and antibodies recognizing ADP with a terbium complex (figure 15). Using a competitive assay format and a ratiometric measurement of the QD emission to terbium emission, they obtained a limit of detection of 10 nM ADP and a quantitation limit of 35 nM in a 20 μL sample volume using an 8 nM sensor concentration. Their sensor was further tested in an enzyme assay of glucokinase (GLK) and showed the ability to differentiate structurally similar enzyme inhibitors. Increasing concentrations of GLK favored faster reaction rates, and kinetic parameters could be determined from their experiments yielding specificity constant of 210 ± 100 Mm−1 s−1, and . Inhibitory constant (Ki) for the coenzyme palmityl-CoA was determined to be 1.0 ± 0.2 μM in their buffer conditions, for a reported Ki of 2μM in literature [21].

Figure 15:

Schematic representation of His6-ADP self-assembly on Zn2+ surface of QD and Tb labelled antibodies recognizing ADP. Upon UV excitation, FRET from Tb to the QD results in quenching of the Tb emission and sensitization of the QD emission (red curve). Upon addition of free ADP, the Tb-antibody detaches from the QD causing a decrease in QD emission and increase in Tb emission. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [21] Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.