Abstract

The ability to transform two-dimensional (2D) structures into three-dimensional (3D) structures leads to a variety of applications in fields such as soft electronics, soft robotics, and other biomedical-related fields. Previous reports have focused on using electrospun nanofibers due to their ability to mimic the extracellular matrix. These studies often lead to poor results due to the dense structures and small poor sizes of 2D nanofiber membranes. Using a unique method of combining innovative gas-foaming and molding technologies, we report the rapid transformation of 2D nanofiber membranes into predesigned 3D scaffolds with biomimetic and oriented porous structure. By adding a surfactant (pluronic F-127) to poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) nanofibers, the rate of expansion is dramatically enhanced due to the increase in hydrophilicity and subsequent gas bubble stability. Using this novel method together with molding, 3D objects with cylindrical, hollow cylindrical, cuboid, spherical, and irregular shapes are created. Interestingly, these 3D shapes exhibit anisotropy and consistent pore sizes throughout entire object. Through further treatment with gelatin, the scaffolds become superelastic and shape-recoverable. Additionally, gelatin-coated, cube-shaped scaffolds were further functionalized with polypyrrole coatings and exhibited dynamic electrical conductivity during cyclic compression. Cuboid-shaped scaffolds have been demonstrated to be effective for compressible hemorrhage in a porcine liver injury model. In addition, human neural progenitor cells can be uniformly distributed and differentiated into neurons throughout the cylinder-shaped nanofiber scaffolds, forming ordered 3D neural tissue constructs. Taken together, the approach presented in this study is very promising in the production of pre-molded 3D nanofiber scaffolds for many biomedical applications.

I. INTRODUCTION

Transforming two-dimensional (2D) structures into three-dimensional (3D) structures is important for many potential applications, including soft electronics,1–3 soft robots and actuators,4,5 photodetection, imaging,6 and other related biomedical fields.7 Origami- and kirigami-based approaches are popular methods for converting 2D sheets/membranes to 3D structures.8,9 The principles of these approaches are often based on mechanical buckling,1,4,5,10 and external environments induced shape memory/recovery.11–15 Due to their extracellular matrix (ECM)-mimicking capability, electrospun nanofibers have been widely used in building tissue models and regenerating tissues.16,17 However, traditional electrospinning often produces 2D nanofiber membranes with dense structures and small pore sizes, preventing the cell infiltration necessary to form 3D tissues.18,19 Though origami- and kirigami-based approaches may offer a modality by which electrospun mats may be transformed into 3D structures, the necessary cuts and folds may be difficult to make precisely.

Several recent studies reported using a gas-foaming technique to expand 2D nanofiber membranes into cuboid and cylinder-shaped 3D scaffolds with layered structures. Such scaffolds showed enhanced cell seeding uniformity and infiltration made possible by the significant between-layer gaps.20–22 In these studies, the cells still failed to penetrate through the thin nanofiber layers due to the dense mat structure and small pore size.23 Also, these studies were limited to the fabrication of certain shapes such as cuboids and cylinders.20,24 Using a similar method in a previous study, nanofiber mats were expanded by depressurization of subcritical CO2 fluid, though the resulting scaffolds still endured the same setbacks of the gas-foam expanded scaffolds—small pores and impenetrable nanofiber layers.25 Most recently, we combined the solids-of-revolution concept and gas-foaming expansion to successfully produce cylinders, cones, and spheres with controlled pore and fiber alignment.26 Though the aforementioned study proved a significant advancement in 3D scaffolds, the technique is limited to producing symmetrical shapes. Furthermore, the fibers were not uniformly distributed throughout the 3D objects. For example, the cylinder-shaped objects had a higher density of fibers at the center and a lower density of fibers at the peripheral site. The disparity of fiber density in 3D objects causes nonuniform cell distribution and 3D tissue formation, which is not ideal for the regeneration of nerve, muscle, and long bone tissues.

To address the above issues, we report for the first time a fast transformation of 2D nanofiber membranes into pre-molded 3D scaffolds with a biomimetic and oriented porous structure by gas-foaming technology in confined molds. Compared with previous approaches, the technology developed in this work can produce irregular 3D shapes using a customized mold, in which nanofibers would be uniformly distributed and cells would be able to proliferate in all directions.

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. Materials

Agar, gelatin, pluronic® F-127 (F-127), poly(ε-caprolactone) PCL (Mw = 80 kDa), sodium borohydride, Triton X-100, polypyrrole, and FeCl3.6H2O were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and Dichloromethane (DCM) were ordered from BDH Chemicals (Dawsonville, GA, USA). Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin-streptomycin, Tuj 1 primary antibody, and laminin were obtained from MilliporeSigma (Burlington, MA, USA). Basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2), epidermal growth factor (EGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) were obtained from Peptrotech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). The ReNcell Neural Stem Cell Medium was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). Goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 546) secondary antibody and DAPI were ordered from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA).

B. Fabrication of 2D PCL/F-127 electrospun nanofiber mats

In order to determine the minimum effective F-127 concentration, concentrations of 0%, 0.5%, 1%, and 2% were explored in this study. Different concentrations of 2D PCL/F-127 electrospun nanofiber mats were fabricated as follows. Two grams PCL beads and 0.1, 0.2, or 0.4 g F-127 were dissolved in 16 ml DCM and 4 ml DMF, respectively. Final concentrations were: PCL at 10%, and F-127 at 0.5%, 1%, and 2%, respectively. After the PCL/F-127 solution was homogenous, 50 ml PCL/F-127 solution was pumped at a flow rate of 0.7 ml/h using a syringe pump while a potential of 18 kV was applied between the spinneret (22 Gauge needle) and a grounded collector. Finally, a nanofiber mat which was around 1 mm thick aligned PCL/0.5% F-127, PCL/1% F-127, PCL/2% F-127 was collected by a high-speed rotating drum.

C. Expansion of 2D F-127/PCL electrospun nanofiber mats

Resulting PCL/F-127 electrospun nanofiber mats were first immersed into 1 M NaBH4 solution and treated with a vacuum for 3 s. The fiber mats were then continuously expanded in 1 M NaBH4 solution for another 30 s at ambient condition. Finally, the expanded scaffolds were washed with cold distilled water 5 times, vacuum treated for 5 s, and freeze-dried.

D. Expansion of tube scaffolds with different pore size

Similarly, 5 mm × 10 mm × 1 mm, 5 mm × 10 mm × 0.75 mm, 5 mm × 10 mm × 0.5 mm, 5 mm × 10 mm × 0.25 mm 2D 0.5% F-127/PCL nanofiber mats were cut and put into a 1 ml syringe (5 mm in diameter), then immersed into 1 M NaBH4 solution and vacuum treated for 3 s. The fiber mats were then continuously expanded in 1 M NaBH4 solution for another 30 s at ambient condition. Finally, the expanded tubular scaffolds were washed with cold distilled water 5 times and then treated with a vacuum for 5 s and freeze-dried.

E. 3D molds with different shapes

The hollow cylinder, tube, and sphere-like molds were printed by a 3D printer. The hollow fish, chicken leg, and bread-like molds were obtained from a kids' Play-Doh Modeling Compound Set.

F. Confined expansion

The PCL/0.5% F-127 nanofiber mats were cut into different shapes while submerged in liquid nitrogen to prevent fiber sintering. Subsequently, PCL/0.5% F-127 nanofiber mats were put into molds and immersed in 1 M NaBH4 solution and vacuum treated for 3 s. After the vacuum was removed, expansion could continue for 30 s. After expansion, the scaffolds were transferred into distilled water and again vacuum treated (∼200 Pa) for 5 s. This process was repeated 3 times. Finally, the distilled water was removed and the 3D scaffolds were freeze-dried. To enhance the mechanical property of the 3D scaffolds, they were immersed in 0.5% gelatin solution for 10 min. The residual gelatin solution was then removed. Gelatin-coated 3D scaffolds were vacuum-treated until frozen and then freeze-dried. No cross-linking was performed for the gelatin coating.

G. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) characterization

The photographs of complex 3D scaffolds were recorded by a digital camera. The cross sections of 3D scaffolds were characterized by SEM (FEI Quanta 200, FEI Company, Hillsboro, Oregon, USA).

H. Contact angle measurement

The contact angles of PCL, 0.5% F-127/PCL, 1% F-127/PCL, and 2% F-127/PCL nanofiber mats were measured using a DM500 instrument (Kyowa Interface Science Co. Ltd., Saitama, Japan) at room temperature. The contact angles were measured immediately every 1 s and duration 5 s after 5 μl of de-ionized water was dropped on the surface of PCL, 0.5% F-127/PCL, 1% F-127/PCL, and 2% F-127/PCL nanofiber mats, respectively.

I. Polypyrrole coating and conductivity characterization

The expanded PCL/0.5% F-127 nanofiber scaffold (1 cm × 1 cm × 4 cm) was immersed in a 0.04 M pyrrole aqueous solution, and then mixed with an equivalent volume of 0.084 M FeCl3 aqueous solution at room temperature. The mixture was put into an ultrasonic cleaning basin for 30 min to make the polymerization uniform.27,28 A battery-powered circuit (3 V) was set up and used to detect the conductivity of polypyrrole-coated expanded PCL/0.5% F-127 nanofiber scaffolds under different compressive strains. The conductivity of the nanofiber scaffold under different compressive strains was visualized by a light-emitting diode (LED) light. The resistance of the nanofiber scaffold under different compressive strains was measured by a multimeter.

J. Mechanical tests

The mechanical properties of PCL nanofiber shapes and 0.5% gelatin-coated, cuboid-shaped PCL nanofiber shapes were recorded with an Instron 5640 Universal Test Machine. Samples (20 mm× 10 mm × 10 mm) were subjected to cyclic compressive tests. The compressive strain was set as 50%, 70%, and 90%, respectively. The mechanical tests were run in 5 cycles at a speed of 18 mm/min. To examine the superelastic property of 0.5% gelatin-coated, cuboid-shaped nanofiber scaffolds, 20 cycles with a speed of 18 mm/min under 90% compressive strain were employed. The elastic modulus was obtained from the initial slope before 30% compressive strain. The energy loss coefficient is calculated as ΔU/U = (the area of the compression curve and the abscissa − the area of the recovery curve and the abscissa) / the area of the compression curve and the abscissa.

K. Human neural stem/progenitor cell culture

Human neural stem/progenitor cells (hNSCs) were obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Laminin (20 μg/mL, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to coat tissue culture plates at least 4 h before cell seeding to promote the attachment of hNSCs. The hNSCs were maintained in ReNcell Neural Stem Cell Medium (Millipore) 15 with FGF-2 (20 ng/mL) and EGF (20 ng/mL) at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Prior to hNSCs seeding, tubular nanofibers were sterilized with ethylene oxide for 12 h and eventually coated with laminin (20 μg/mL) for 2 h. After scaffold treatment, a 20 ml suspension of hNSCs at a concentration of 1 × 107 cell/ml was prepared. Tubular nanofiber scaffolds were put into the cell suspension solution and treated with a vacuum for 10 s. After vacuum treatment, tubular nanofiber scaffolds with hNSCs were moved into a 6-well plate with 0.1% w/v agar-coated wells and continuously cultured for 1 week. Culture medium was changed every 2 days. After 1 week of culture, BDNF (20 ng/mL) and GDNF (20 ng/mL) were added to the medium to start hNSC differentiation for another 2 weeks.

L. Immunofluorescence staining

Prior to staining, hNSC-seeded nanofiber tubes were washed with PBS 3 times for 5 min each wash before fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) solution for 20 min, washed with PBS 3 times for 5 min each time. Next, they were blocked with 5% goat serum for 30 min. Cells were then incubated with Tuj1 (1:100) primary antibodies overnight and washed with PBS 3 times for 5 min each wash, then incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 546) secondary antibody (1:200) for 1 h and washed with PBS 3 times for 5 min for each wash. Finally, cells were imaged by confocal laser scanning microscopy (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). During imaging, 50 μL distilled water was added to each scaffold to prevent drying. Images from the z-stack range from 0 μm to 150 μm with interval slices at 5 μm. The tile scan was set as 4 × 4 and the cold depth of Zeiss blue software was used to code cells at different depths with corresponding colors.

M. Hemostasis in vivo test

Details of the animal model are described in the supplementary material. Briefly, the left medial lobe of the liver was exteriorized through the midline incision, and then resected at its base using a short, curved, single scissors (4 cm blade). The level of resection was at the junction of the left median (LM) lobe with the right median (RM) lobe producing a combined portal/hepatic venous injury. Immediately after resection, a 0.5% gelatin-coated, 0.5% F-127/PCL nanofiber sponge (12 cm × 10 cm area) was applied onto the bleeding resection site, and bimanual compression was performed to hold the bandage onto the injury site for 5 min. This compression technique consisted of one hand placed over the liver dome, while the other hand pushed against the bandage, effectively “sandwiching” the bandage and liver between the operator's hands. The animal study in this work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System (Protocol number 1109).

N. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. Differences among groups were assessed using student's T-test and one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc tests. The values of *p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The values of **p < 0.01 were considered very statistically significant.

III. RESULTS

A. The additive Pluronic F-127 boosts the expansion of PCL nanofiber mats

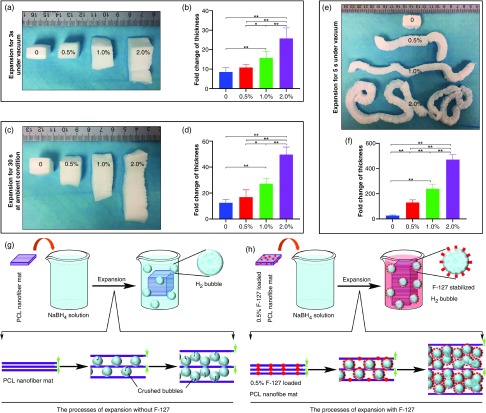

Before testing the transformation of 2D nanofiber mats in the 3D molds, we first examined the influence of a surfactant additive F-127 on the expansion of PCL nanofiber membranes. Here, PCL nanofibers containing 0%, 0.5%, 1%, and 2% of F-127 were prepared by electrospinning. The contact angles of PCL fibers incorporating F-127 changed from 138° to 0° as shown in Fig. S1 (see the supplementary material), indicating that the addition of F-127 enhances hydrophilicity. Following our previous studies, PCL nanofiber mats containing 0%, 0.5%, 1%, and 2% of F-127 were first expanded in NaBH4 solution (1 M) for 3 s under vacuum condition [Fig. 1(a)], then expanded in NaBH4 solution (1 M) at ambient conditions for another 30 s [Fig. 1(c)], and then further expanded in the NaBH4 solution (1 M) for 3–4 s under vacuum condition [Fig. 1(e)]. Fold changes of nanofiber mat thickness following expansion are shown in Figs. 1(b), 1(d), and 1(f). Evidently, the addition of F-127 can substantially enhance the expansion of 2D nanofiber membranes from 2.68 ± 0.41 cm (without F-127) to 13.03 ± 2.03 cm (0.5% F-127), 23.89 ± 3.69 cm (1% F-127), and 47.09 ± 4.01 cm (2% F-127) thick [Fig. 1(f)]. We also examined the effect of adding F-127 directly to the solution on the expansion of PCL nanofiber mats pretreated with plasma for 1 min. It seems that the additional F-127 could promote the expansion of nanofiber mats in the first 12 h. However, after 24 h of expansion, no significant difference was observed for all the samples. Even after expansion for 5 s under vacuum, the final lengths of all the samples showed no significant difference (see the supplementary material, Fig. S2).

FIG. 1.

The effect of the additive surfactant pluronic F127 (F-127) on the expansion of PCL nanofiber mats. (a) Photographs showing the morphology of PCL nanofiber mats and 0.5%, 1%, and 2% F-127 loaded PCL nanofiber mats that were pre-expanded in 1 M NaBH4 solution for 3 s under vacuum condition. (b) The lengths fold changes of the length after pre-expansion (3 s before expansion). (c) Photographs showing the morphology of pre-expanded nanofiber mats in (a) that were sequentially expanded in 1 M NaBH4 solution for 30 s at ambient condition. (d) The lengths fold changes of the length after expansion and 30 s before expansion. (e) Photographs showing the morphology of expanded nanofiber mats in (a,c) that were expanded in 1 M NaBH4 solution for 35 s under vacuum, then freeze-dried conditions. (f) The length fold changes of the final length of scaffold after freeze-dry and before expansion. 0: PCL nanofiber mats. 0.5%: 0.5% F-127 loaded PCL nanofiber mats. 1.0%: 1% F-127 loaded PCL nanofiber mats. 2.0%: 2% F-127 loaded PCL nanofiber mats. (n = 5, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). (g) Schematic illustrating the expansion process of PCL nanofiber mats without addition of F-127. The H2 bubbles tend to escape. (h) Schematic illustrating the expansion process of PCL nanofiber mats with addition of F-127. The F-127 additive enhances the hydrophilicity and water penetration of PCL nanofiber mats and, meanwhile, the H2 bubbles are stabilized by F-127 molecules, resulting in a faster expansion. Two green arrows indicate the gap between nanofiber layers.

B. Fast transformation of 2D nanofiber mats into pre-molded 3D scaffolds with oriented porous structure

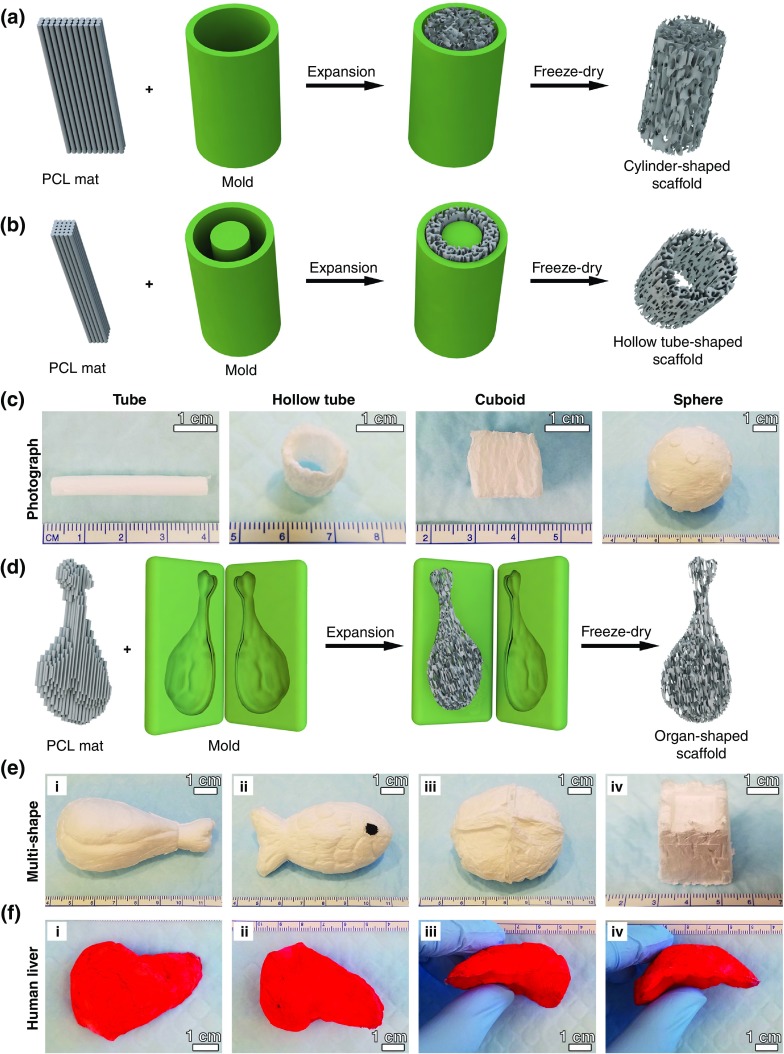

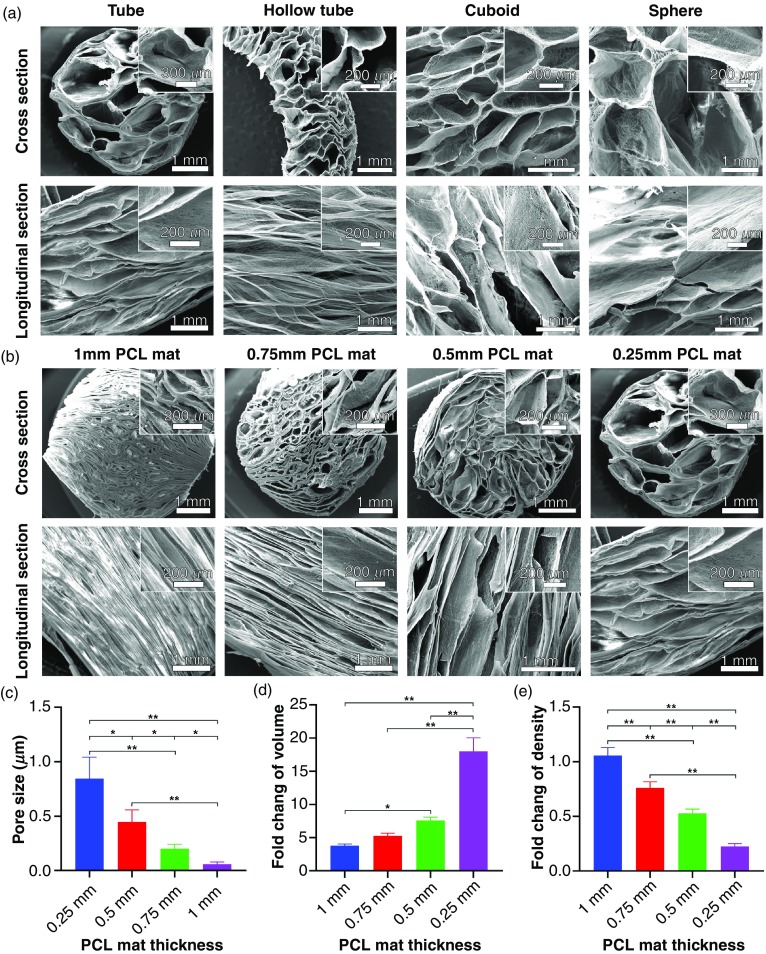

After enhancing expansion with F-127, we used molds to expand 0.5% F-127-loaded PCL nanofiber membranes into 3D scaffolds. Figures 2(a) and 2(b) illustrate the transformation of 2D nanofiber membranes in two different molds: a hollow tube with and without a cylinder in the center, which resulted in cylinder and hollow tube-like 3D nanofiber scaffolds. Figure 2(c) shows photographs of transformed 3D scaffolds with cylinder and hollow tube shapes, respectively. We also achieved cuboid-shaped and sphere-shaped scaffolds using molds of two half-hollow spheres and a cuboid-shaped box [Fig. 2(c)]. Mold-guided expansion is an important first step in creating 3D nanofiber scaffolds of irregular shapes, some of which are illustrated in Figs. 2(d)–2(f), including a chicken leg, fish, bread, castle, and human liver. Therefore, it is possible to create custom scaffolds that perfectly fit the shapes of tissue defects without much post-fabrication treatments, such as sanding, cutting, or shaving. Figure 3(a) shows SEM cross-sectional and longitudinal images of 3D scaffolds shown in Fig. 2(c), indicating the biomimetic and oriented porous structure. The porosity and pore size of transformed scaffolds could be tuned by varying the sizes of initial nanofiber mats. Figure 3(b) shows the cylinder-shaped nanofiber scaffolds with tunable pore size and porosity by simply expanding fiber mats with different thicknesses in a tube-shaped mold. For the 1-mm, 0.75-mm, 0.5-mm, and 0.25-mm thick fiber mats, the pore sizes and volume change of correspondingly resultant scaffolds were 0.84 ± 0.134 mm, 0.44 ± 0.112 mm, 0.20 ± 0.004 mm, and 0.06 ± 0.021 mm, and 3.93, 5.23, 7.85, and 10.46, respectively [Figs. 3(c) and 3(d)].

FIG. 2.

Fast transformation of 2D nanofiber mats into pre-molded 3D scaffolds with oriented porous structure. Schematic illustrating the procedure of converting a 2D nanofiber mat into a cylinder-shaped nanofiber scaffold (a) and hollow tube-shaped scaffold (b) by expanding the mat in customized molds. (c) Photographs of transformed, cylinder-shaped, hollow tube-shaped, cuboid-shaped, and sphere-shaped nanofiber scaffolds. 3D nanofiber scaffolds with irregular shapes produced through confined expansion in irregular spaces. (d) Schematic illustrating the procedure of converting a 2D nanofiber mat into an irregular-shaped nanofiber scaffold by expanding the mat in a customized, irregular-shaped mold. (e) The photographs showing the transformed 3D scaffolds with chicken leg-like shape (i), fish-like shape (ii), bread-like shape, (iii) and castle-like shape (iv). (f) The photographs showing the top view (i), bottom view (ii), and side view (ii and iv) of a 3D scaffold with human liver-like shape. The fibers were stained with 1% (w/v) rhodamine 6 G in red.

FIG. 3.

The internal structure characterization of confined, expanded nanofiber scaffolds. (a) SEM images showing cross section and longitudinal section of cylinder-shaped, hollow tube-shaped, cuboid-shaped, and sphere-shaped scaffolds. Cylinder-shaped nanofiber scaffolds with tunable pore sizes and porosities. (b) SEM images showing the cross section and longitudinal section of cylinder-shaped nanofiber scaffolds expanded from fiber mats that are 1 mm, 0.75 mm, 0.5 mm, and 0.25 mm thick. Insets: the corresponding magnified images. Pore sizes (c), relative volume change (volume of scaffold after expansion/volume of nanofiber mat), and (d) relative density fold change (density of scaffold after expansion/density of nanofiber mat) (e) of cylinder-shaped nanofiber scaffolds expanded from fiber mats with different thicknesses. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

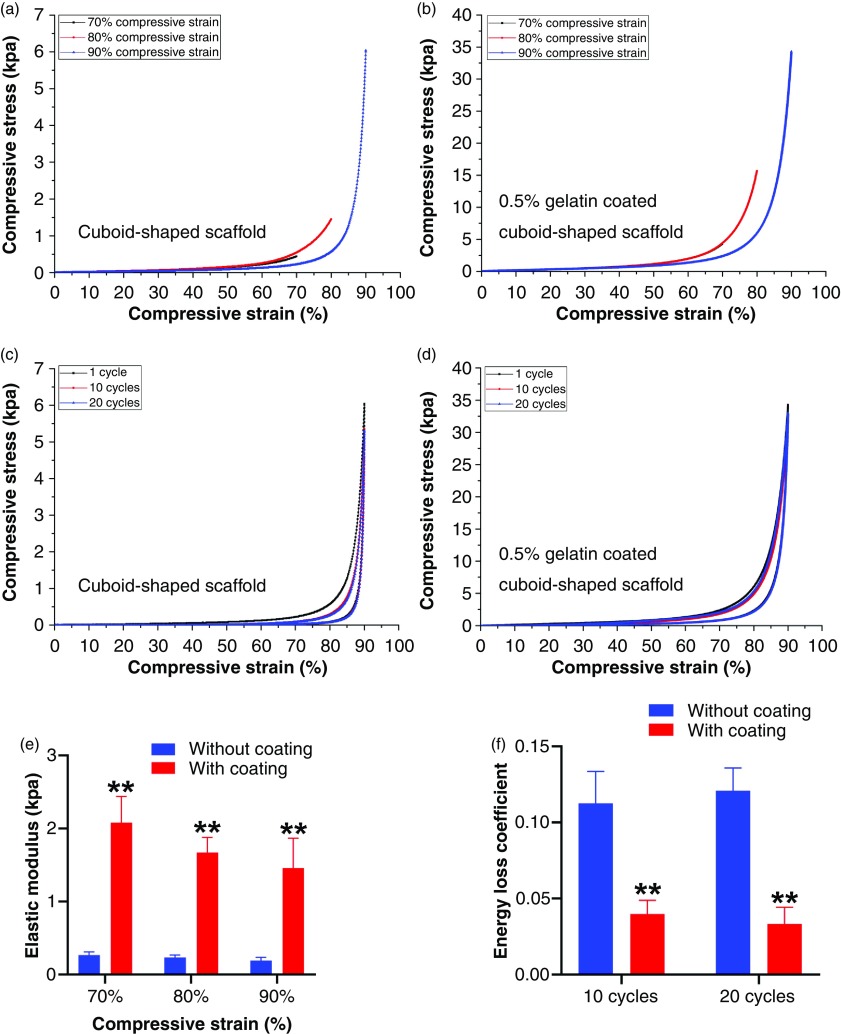

Due to the geometric strain for mechanical tests, we then performed the cyclic compressive tests of cuboid-shaped nanofiber scaffolds (20 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm) with and without 0.5% gelatin-coating [Figs. 4(a)–4(d)], revealing the superelastic and shape-recovery property. Consistent with our previous studies, gelatin-coating can enhance the elastic modulus under different compressive strains [Fig. 4(e)].24 In contrast, the gelatin coating reduced the energy loss coefficient after 10 cycles and 20 cycles of compressive tests [Fig. 4(f)]. Similarly, the hollow tube-shaped nanofiber scaffolds also exhibited the excellent shape-recovery property after releasing the compression (see the supplementary material, Video 3).

FIG. 4.

Mechanical property of transformed 3D nanofiber scaffolds. (a) Compressive tests of cuboid-shaped nanofiber scaffolds (dimension: 20 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm) under 70%, 80%, and 90% compressive strains. (b) Compressive tests of 0.5% gelatin-coated, cuboid-shaped nanofiber scaffolds under 70%, 80%, and 90% compressive strains (the 70% compression curve is behind the 80% compression curve). (c) Cyclic compressive tests of cuboid-shaped nanofiber scaffolds under 90% compressive strain (1, 10, and 20 cycles). (d) Cyclic compressive tests of 0.5% gelatin-coated, cuboid-shaped nanofiber scaffolds under 90% compressive strain (1, 10, and, 20 cycles). (e) Elastic modulus of cuboid-shaped nanofiber scaffolds with and without 0.5% gelatin coating under different compressive strains. (f) Energy loss coefficients of cuboid-shaped nanofiber scaffolds with and without 0.5% gelatin coating under different compressive strains. **p < 0.01.

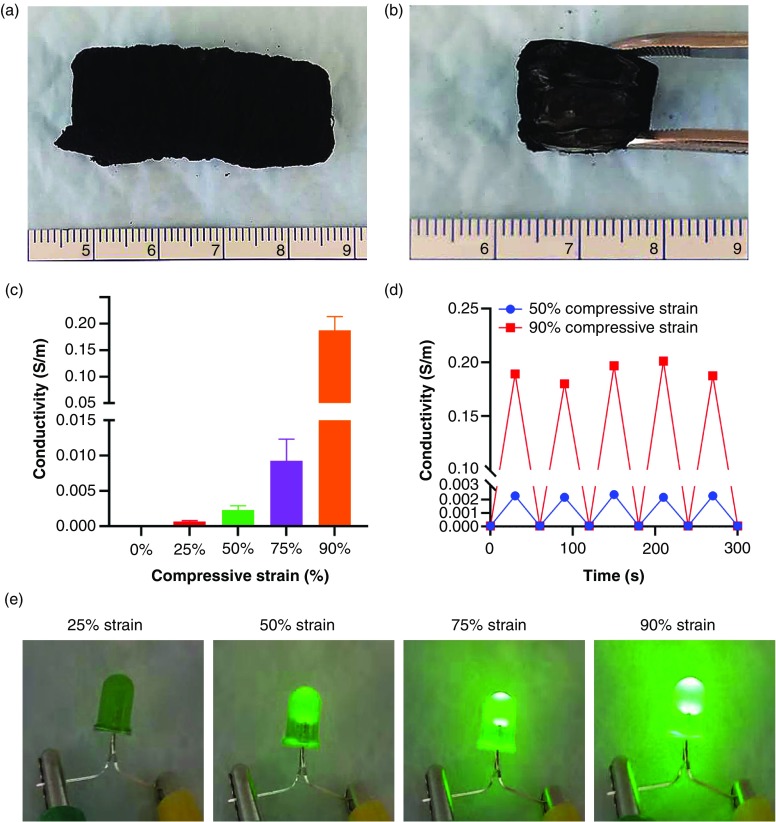

C. Functionalization of transformed 3D 0.5% F-127/PCL nanofiber scaffolds

The transformed 3D scaffolds can be further functionalized based on different requirements such as conducting electricity. To induce electrical conductivity, we coated expanded cuboid-shaped PCL/0.5%F-127 nanofiber scaffolds with conductive polypyrrole using in situ polymerization of pyrrole. Figure 5(a) shows a cuboid-shaped scaffold after coating with polypyrrole in black. Figure 5(b) shows the inside view of the scaffold in Fig. 5(a), indicating the relatively uniform coating of polypyrrole throughout the 3D nanofiber scaffold. Conductivity of the scaffold increased with increasing compressive strain [Fig. 5(c)]. Polypyrrole-coated scaffolds showed cyclic conductivity under 50%, 75%, and 90% compressive strains [Fig. 5(d)], which is likely due to the reduction of distances between the expanded nanofiber layers. Moreover, the cyclic conductivity of polypyrrole-coated 3D nanofiber scaffolds was demonstrated in Fig. 5(e). A customized battery-powered circuit (3 V) was used to demonstrate the conductivity of polypyrrole-coated 3D nanofiber scaffolds under different compressive strain (see the supplementary material, Fig. S4). The LED light failed to light up polypyrrole-coated 3D nanofiber scaffolds under 25% compressive strain or less. The LED light started to light up under 50% compressive strain, and the light intensity increased from 50% compressive strain to 90% compressive strain.

FIG. 5.

Functionalization of transformed 3D 0.5% F-127/PCL nanofiber scaffolds. (a) The photograph of a polypyrrole-coated 0.5% F-127/PCL nanofiber scaffold. (b) The inside view of a polypyrrole-coated 0.5% F-127/PCL nanofiber scaffold. (c) The electrical conductivity of polypyrrole-coated, 0.5% F-127/PCL nanofiber scaffolds under 25%, 50%, 75%, and 90% compressive strains. (d) The cyclic conductivity of transformed, polypyrrole-coated, 0.5% F-127/PCL nanofiber scaffolds under 50% and 90% compressive strains (5 cycles). (e) A battery-powered circuit (3 V) was used to demonstrate different conductivities of polypyrrole-coated 3D nanofiber scaffolds under 25%, 50%, 75%, and 90% compressive strains.

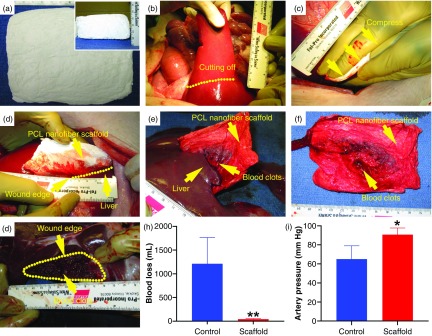

D. The hemostatic application of transformed, cuboid-shaped 0.5% F-127/PCL nanofiber scaffolds

We successfully transformed large size PCL mats (12 cm × 10 cm× 0.1 cm) to 3D nanofiber scaffolds (12 cm × 10 cm × 3 cm) [Fig. 6(a)]. To meet different requirements of the biomedical application, the expanded large nanofiber scaffolds could be precisely cut into small pieces, or they could be further cut into regular- or irregular-shaped scaffolds using laser cutting (see the supplementary material, Fig. S5). Here, we demonstrated the applications of large size cuboid-shaped 3D scaffolds in compressible hemorrhage. A porcine liver section model was created following our previous studies [Fig. 6(b)].29 A scaffold was applied to the sectioned porcine liver by applying manual compression for 5 mins, and the subject was observed for another 55 mins [Figs. 6(c) and 6(d)], before the scaffold was peeled off from the injury site [Figs. 6(e) and 6(f)]. The scaffold adhered to the injury, and clotting was observed within the injury site [Fig. 6(g)]. Injury model pigs with nanofiber scaffold treatments had less blood loss and higher mean artery pressure compared to untreated pigs (43 ± 12 ml vs 1213 ± 552 ml, n = 3, p = 0.000; 90 ± 7 mm Hg vs 656 ± 16 mm Hg; n = 3, p = 0.034; respectively) [Figs. 6(h) and 6(i)]. This result suggests the potential of transformed 3D nanofiber scaffolds for the management of compressible hemorrhage secondary to trauma or during elective surgery.

FIG. 6.

The hemostatic application of transformed, cuboid-shaped 0.5% F-127/PCL nanofiber scaffolds in a porcine model of liver resection. (a) The top and side (inset) views of cuboid-shaped 0.5% F-127/PCL nanofiber scaffolds. (b) Left medial lobe resection performed along the indicated dots line. (c) Bimanual compression of nanofiber scaffolds against the resection site with hands for 5 min. (d) Injury site covered with PCL nanofiber scaffolds immediately after the 5 min period of bimanual compression, hemorrhage has stopped. (e) Liver ex vivo after the 1 h observation period; and the nanofiber scaffold bandage is adherent to the injury site. (f) The nanofiber scaffold after it was peeled away from the injury site. (g) The injury site after the nanofiber scaffold was peeled off. (h,i) The quantification of blood loss (h) and artery pressure (i) for the control (untreated group) and nanofiber scaffold treatment groups after 60 min. (n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

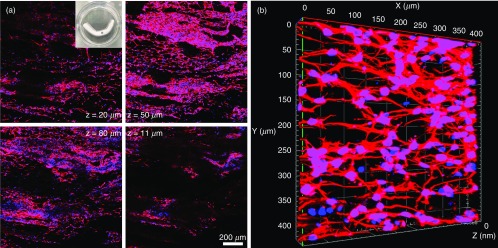

E. In vitro culture of hNSCs on transformed, tubular-shaped nanofiber scaffolds

Based on the confined expansion, we also demonstrated the successful fabrication of porous tubular and hollow-tubular nanofiber scaffolds with controlled alignment and porosity, which may have great potential in the regeneration of nerves, muscles, or blood vessels. In this study, we cultured human neural stem/progenitor cells (hNSCs) on tubular scaffolds consisting of longitudinally aligned PCL nanofibers. Figure 7(a) shows cells widely distributed throughout the 3D tubular scaffolds. The inset shows a photograph of tubular scaffolds seeded with hNSCs. The majority of these cells were Tuj1-positive, indicating neuronal differentiation. In addition, neurites extended from these cells were organized into a 3D ordered structure, forming a 3D neuronal network within the scaffold [Fig. 7(b)]. Therefore, we could use transformed 3D nanofiber scaffolds to generate various 3D neural tissue constructs with complex and ordered structures.

FIG. 7.

In vitro culture of hNSCs on transformed, cylinder-shaped nanofiber scaffolds (4 cm in length, 3 mm in diameter, initial fiber mat thickness = 0.5 mm). (a) Cell distribution of human neural progenitor cells in different depths of cylinder-shaped nanofiber scaffolds after neuronal differentiation for 14 days. Inset: a photograph showing a transformed, cylinder-shaped nanofiber scaffold seeded with hNSCs. (b) The 3D confocal microscopy image showing the formation of 3D neuronal networks inside the scaffold after neuronal differentiation for 14 days. Cells were stained with Tuj 1 for neurons in red, and cell nuclei were stained with DAPI in blue.

IV. DISCUSSION

Recent studies reported 3D and 4D electrospinning technologies based on 3D printing of short nanofibers or stimuli-responsive, self-folding nanofiber mats. These technologies are limited to certain materials, shapes, and fiber orientations (mostly random fibers),30–32 and result in limited applications in tissue regeneration. Interest in developing aligned and controllable 3D fiber objects remains a key goal for many researchers in regenerative medicine. Our recent studies addressed the problem of the dense structure of traditional electrospun nanofiber scaffolds, which has plagued the electrospinning field for decades, by making use of innovative gas-foam technology.20,22,24 However, this technology was associated with some limitations. The expansion process was inefficient and time-consuming, taking at least 12 h with a successful rate of approximately 70%.20,22,24 The expansion throughout the scaffold was not very uniform, especially in the central region.20,22,24,26 Expanding nanofiber mats into irregular shapes was not possible with this technique. Controlling pore size and fiber orientation during expansion proved difficult, and the dimension of expanded scaffolds was relatively small. These limitations restricted the applications of expanded nanofiber scaffolds in the biomedical field.20,22,24,26 In the presented study, though, the surfactant F-127 [approximately 70 wt. % hydrophilic polyethylene oxide (PEO) and 30 wt. % of hydrophobic polypropylene oxide (PPO)] was blended to PCL nanofibers, resulting in an accelerated and uniform expansion of 2D nanofiber mats. In addition, the expansion of PCL/F-127 nanofiber mats was not affected by their scaled-up sizes. We speculate that the potential mechanism could be as follows: (i) the enhanced hydrophilicity led to the fast water penetration; and (ii) the reduction of surface tension and inhibition of diffusion of gas molecules by surfactant on the interface between gas and liquid leading to the stabilization of gas bubbles and the increase in the lifetime of gas bubbles [Figs. 1(g) and 1(h); see the supplementary material, Video 1 and Video 2, Fig. S3].33–35

To develop irregularly shaped 3D scaffolds, something that was not possible in the past, we combined gas-foaming and molding technologies, coining the technique as “confined expansion” and generated nanofiber scaffolds with customized and pre-molded shapes. Damaged tissue dimensions could be reliably reproduced, yielding scaffolds that perfectly fit injury sites. The geometric shape of tissue defects can be reconstructed by imaging modalities or hydrogel molding. Using the mold, a model can be generated by 3D printing and immediately used for confined expansion. Alternatively, the customized 3D scaffolds can be fabricated by laser cutting of expanded nanofiber scaffolds as indicated in Fig. S5 (see the supplementary material). Such pre-molded nanofiber scaffolds with biomimetic and oriented porous structure could be used for regeneration of various tissues. For example, tissues such as peripheral nerves have an anisotropic structure. Previous synthetic nanofiber scaffolds failed to completely recapitulate the anatomic structures of peripheral nerve tissues.36 In this work, the transformed, cylinder-shaped nanofiber scaffolds can better mimic the peripheral nerve tissue structures when compared to decellularized nerve scaffolds.37 The in vitro culture of hNSCs suggest that the formed neural tissue constructs could be used as in vitro 3D tissue models for understanding neural development, modeling neurological diseases, screening tests for drug discovery, or regenerating solutions for traumatic brain or spinal cord injuries or neurodegenerative diseases.38,39 Similarly, the transformed scaffolds could be used to fabricate other types of 3D tissue models such as muscle and tendon.

In order to further the applications of expanded nanofiber scaffolds in biomedical fields, transformed 3D nanofiber scaffolds can be further functionalized by material blending, chemical modification, and physical absorption.40 In this study, expanded scaffolds were functionalized with a polypyrrole coating, and conductivity increased with compression that was due to the reduction of in distances between the expanded nanofiber layers.41

Such scaffolds could be used as novel electrode materials or matrices for recording, compression sensing, stimulation, and regeneration of tissues.42 Besides the conductive functionalization, 3D nanofiber scaffolds can be further functionalized with pH-responsive, thermo-responsive, light-responsive, magnetic-responsive, and multi-responsive properties by careful material selection.43 Moreover, flexible electronics can be embedded in these expanded nanofiber scaffolds to manufacture sensory skins, implantable medical devices, and soft robotics.44 With the right material selection, these shape-controlled, expanded 3D nanofiber scaffolds have a vast range of applications in biomedical sciences and beyond.

In addition, large size PCL mats (12 cm × 10 cm × 0.1 cm) were successfully transformed to 3D nanofiber scaffolds (12 cm × 10 cm× 3 cm) with uniform pores. The thickness of the large size 3D nanofiber scaffold after expansion could reach 6–7 cm, when previously we could only generate scaffolds with a dimension of 8 cm × 8 cm× 0.5 cm after overnight expansion.22,24 We speculate that the uniform expansion of large size mats was due to the enhanced hydrophilicity and stabilized gas bubbles rendered by the surfactant additive F-127. Our previous study showed the small size of “peanuts” PCL nanofiber scaffolds could have a higher capacity of blood absorption and fast hemostasis than current commercial products including Surgicel®, gelatin foam, and gauze, suggesting the potential in the management of non-compressible torso hemorrhage and junctional hemorrhage.24 We further demonstrated the efficacy of large size cuboid-shaped 3D nanofiber scaffolds in compressible hemorrhage using a porcine liver injury model, indicating a great clinical application for stopping bleeding in elective surgical procedures and traumatic injuries.45 Outside of biomedical applications, the ability to scale up expansion of large mats has a wide variety of applications from environmental engineering to power engineering.

V. CONCLUSION

In summary, we demonstrated a unique method of rapidly expanding 2D nanofiber membranes in confined spaces, effectively converting them into pre-molded 3D scaffolds with a biomimetic and oriented porous structure. We also found that blending surfactants with the nanofibers can accelerate the expansion rate of 2D membranes. Cuboid-shaped 3D scaffolds decorated with an electrically conductive polymer showed compression-responsive conductivity, while expanded 3D scaffolds could be used as hemostatic materials. In addition, tubular scaffolds can be used to form anisotropic tissue constructs for mechanistic studies and translational applications. The technology developed in this study shows great potential in the controlled fabrication of 3D biomimetic scaffolds for applications in various biomedical fields, including 3D cell culture, engineering complex tissue models, tissue repair and regeneration, and hemostasis.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

See the supplementary material for details on the detailed hemostasis methods; the contact angle of PCL, 0.5% F-127/PCL, 1% F-127/PCL, and 2% F-127/PCL nanofiber mats; the expansion of PCL nanofiber mats in the 1 M NaBH4 solution containing different amounts of F-127; and the effect of the additive surfactant F-127 to nanofibers on the stability of generated H2 bubbles. Video 1 shows bubble formation after immersing the PCL nanofiber mat in 1 M NaBH4 solution. Video 2 indicates bubble formation after immersing the 0.5% F-127/PCL nanofiber mat in 1 M NaBH4 solution. Video 3 presents the shape recovery of hollow nanofiber tubes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by startup funds from the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC), National Institute of General Medical Science (NIGMS) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01GM123081, Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (CDMRP)/Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program (PRMRP) FY19 W81XWH2010207, UNMC Regenerative Medicine Program pilot grant, Nebraska Research Initiative grant, and NE LB606. This study also was supported in part with resources and the use of facilities at the Omaha VA Medical Center (Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System). The authors would like to acknowledge the technical assistance of Chris Hansen and Gerri Siford.

References

- 1. Xu S., Yan Z., Jang K. I., Huang W., Fu H., Kim J., Wei Z., Flavin M., McCracken J., Wang R., Badea A., Liu Y., Xiao D., Zhou G., Lee J., Chung H. U., Cheng H., Ren W., Banks A., Li X., Paik U., Nuzzo R. G., Huang Y., Zhang Y., and Rogers J. A., Science 347(6218), 154 (2015). 10.1126/science.1260960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moon H., Chou N., Seo H. W., Lee K., Park J., and Kim S., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11(39), 36186 (2019). 10.1021/acsami.9b09578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fan D., Lee B., Coburn C., and Forrest S. R., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116(10), 3968 (2019). 10.1073/pnas.1813001116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nan K., Luan H., Yan Z., Ning X., Wang Y., Wang A., Wang J., Han M., Chang M., Li K., Zhang Y., Huang W., Xue Y., Huang Y., Zhang Y., and Rogers J. A., Adv. Funct. Mater. 27(1), 1604281 (2017). 10.1002/adfm.201604281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fu H., Nan K., Bai W., Huang W., Bai K., Lu L., Zhou C., Liu Y., Liu F., Wang J., Han M., Yan Z., Luan H., Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Zhao J., Cheng X., Li M., Lee J. W., Liu Y., Fang D., Li X., Huang Y., Zhang Y., and Rogers J. A., Nat. Mater 17(3), 268 (2018). 10.1038/s41563-017-0011-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee W., Liu Y., Lee Y., Sharma B. K., Shinde S. M., Kim S. D., Nan K., Yan Z., Han M., Huang Y., Zhang Y., Ahn J. H., and Rogers J. A., Nat. Commun 9(1), 1417 (2018). 10.1038/s41467-018-03870-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Han M., Wang H., Yang Y., Liang C., Bai W., Yan Z., Li H., Xue Y., Wang X., Akar B., Zhao H., Luan H., Lim J., Kandela I., Ameer G. A., Zhang Y., Huang Y., and Rogers J. A., Nat. Electron. 2(1), 26 (2019). 10.1038/s41928-018-0189-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Callens S. J. and Zadpoor A. A., Mater. Today 21(3), 241 (2018). 10.1016/j.mattod.2017.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang Y., Yan Z., Nan K., Xiao D., Liu Y., Luan H., Fu H., Wang X., Yang Q., Wang J., Ren W., Si H., Liu F., Yang L., Li H., Wang J., Guo X., Luo H., Wang L., Huang Y., and Rogers J. A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112(38), 11757 (2015). 10.1073/pnas.1515602112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yan Z., Zhang F., Liu F., Han M., Ou D., Liu Y., Lin Q., Guo X., Fu H., Xie Z., Gao M., Huang Y., Kim J., Qiu Y., Nan K., Kim J., Gutruf P., Luo H., Zhao A., Hwang K. C., Huang Y., Zhang Y., and Rogers J. A., Sci. Adv. 2(9), e1601014 (2016). 10.1126/sciadv.1601014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li G., Wang S., Liu Z., Liu Z., Xia H., Zhang C., Lu X., Jiang J., and Zhao Y., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10(46), 40189 (2018). 10.1021/acsami.8b16094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang S., Li G., Liu Z., Liu Z., Jiang J., and Zhao Y., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11(33), 30308 (2019). 10.1021/acsami.9b10071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hubbard A. M., Mailen R. W., Zikry M. A., Dickey M. D., and Genzer J., Soft Matter 13(12), 2299 (2017). 10.1039/C7SM00088J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu Y., Shaw B., Dickey M. D., and Genzer J., Sci. Adv. 3(3), e1602417 (2017). 10.1126/sciadv.1602417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laskar A., Shklyaev O. E., and Balazs A. C., Sci. Adv. 4(12), eaav1745 (2018). 10.1126/sciadv.aav1745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen S., Li R., Li X., and Xie J., Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 132, 188 (2018). 10.1016/j.addr.2018.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xue J., Wu T., Dai Y., and Xia Y., Chem. Rev. 119(8), 5298 (2019). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Blakeney B. A., Tambralli A., Anderson J. M., Andukuri A., Lim D. J., Dean D. R., and Jun H. W., Biomaterials 32(6), 1583 (2011). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jin G., Shin M., Kim S. H., Lee H., and Jang J. H., Angew. Chem. 54, 7587 (2015). 10.1002/anie.201502177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jiang J., Carlson M. A., Teusink M. J., Wang H., MacEwan M. R., and Xie J., ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 1(10), 991 (2015). 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joshi M. K., Pant H. R., Tiwari A. P., Kim H. J., Park C. H., and Kim C. S., Chem. Eng. J. 275, 79 (2015). 10.1016/j.cej.2015.03.121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jiang J., Li Z., Wang H., Wang Y., Carlson M. A., Teusink M. J., MacEwan M. R., Gu L., and Xie J., Adv. Healthcare Mater. 5(23), 2993 (2016). 10.1002/adhm.201600808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rampichová M., Buzgo M., Chvojka J., Prosecká E., Kofroňová O., and Amler E., Cell Adh. Migr. 8(1), 36 (2014). 10.4161/cam.27477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen S., Carlson M. A., Zhang Y. S., Hu Y., and Xie J., Biomaterials 179, 46 (2018). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.06.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jiang J., Chen S., Wang H., Carlson M. A., Gombart A. F., and Xie J., Acta Biomater. 68, 237 (2018). 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen S., Wang H., McCarthy A., Yan Z., Kim H. J., Carlson M. A., Xia Y., and Xie J., Nano Lett. 19(3), 2059 (2019). 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b00217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee J. Y., Bashur C. A., Goldstein A. S., and Schmidt C. E., Biomaterials 30(26), 4325 (2009). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xie J., MacEwan M. R., Willerth S. M., Li X., Moran D. W., Sakiyama-Elbert S. E., and Xia Y., Adv. Funct. Mater. 19(14), 2312 (2009). 10.1002/adfm.200801904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yanala U. R., Johanning J. M., Pipinos I. I., Larsen G., Velander W. H., and Carlson M. A., PLoS One 9(9), e108293 (2014). 10.1371/journal.pone.0108293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen W., Xu Y., Liu Y., Wang Z., Li Y., Jiang G., Mo X., and Zhou G., Mater. Des. 179, 107886 (2019). 10.1016/j.matdes.2019.107886 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Apsite I., Uribe J. M., Posada A. F., Rosenfeldt S., Salehi S., and Ionov L., Biofabrication 12(1), 015016 (2019). 10.1088/1758-5090/ab4cc4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Apsite I., Stoychev G., Zhang W., Jehnichen D., Xie J., and Ionov L., Biomacromolecules 18(10), 3178 (2017). 10.1021/acs.biomac.7b00829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu B., Takeshita N., Wu Y., Vijayavenkataraman S., Ho K. Y., Lu W. F., and Fuh J. Y. H. J., Mater. Sci. Mater. Med 29(9), 140 (2018). 10.1007/s10856-018-6148-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bird J. C., de Ruiter R., Courbin L., and Stone H. A., Nature 465(7299), 759 (2010). 10.1038/nature09069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dressaire E., Bee R., Bell D. C., Lips A., and Stone H. A., Science 320(5880), 1198 (2008). 10.1126/science.1154601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Panseri S., Cunha C., Lowery J., Del Carro U., Taraballi F., Amadio S., Vescovi A., and Gelain F., BMC Biotechnol. 8(1), 39 (2008). 10.1186/1472-6750-8-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jeffries E. M. and Wang Y., Biofabrication 5(3), 035015 (2013). 10.1088/1758-5082/5/3/035015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhuang P., Sun A. X., An J., Chua C. K., and Chew S. Y., Biomaterials 154, 113 (2018). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marchini A., Raspa A., Pugliese R., El Malek M. A., Pastori V., Lecchi M., Vescovi A. L., and Gelain F., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 116(15), 7483 (2019). 10.1073/pnas.1818392116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sánchez L. D., Brack N., Postma A., Pigram P. J., and Meagher L., Biomaterials 106, 24 (2016). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Darabi M. A., Khosrozadeh A., Mbeleck R., Liu Y., Chang Q., Jiang J., Cai J., Wang Q., Luo G., and Xing M., Adv. Mater. 29(31), 1700533 (2017). 10.1002/adma.201700533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ateh D. D., Navsaria H. A., and Vadgama P., J. R. Soc. Interface 3(11), 741 (2006). 10.1098/rsif.2006.0141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weng L. and Xie J., Curr. Pharm. Des. 21(15), 1944 (2015). 10.2174/1381612821666150302151959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ye D., Ding Y., Duan Y., Su J., Yin Z., and Huang Y. A., Small 14(21), 1703521 (2018). 10.1002/smll.201703521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bennett B. L., Wilderness Environ. Med 28(2), S39 (2017). 10.1016/j.wem.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See the supplementary material for details on the detailed hemostasis methods; the contact angle of PCL, 0.5% F-127/PCL, 1% F-127/PCL, and 2% F-127/PCL nanofiber mats; the expansion of PCL nanofiber mats in the 1 M NaBH4 solution containing different amounts of F-127; and the effect of the additive surfactant F-127 to nanofibers on the stability of generated H2 bubbles. Video 1 shows bubble formation after immersing the PCL nanofiber mat in 1 M NaBH4 solution. Video 2 indicates bubble formation after immersing the 0.5% F-127/PCL nanofiber mat in 1 M NaBH4 solution. Video 3 presents the shape recovery of hollow nanofiber tubes.