Abstract

Background and aim: Healthcare professionals working in palliative care are exposed to emotionally intense conditions. Scientific literature suggests Expressive Writing as a valid tool for the adjustment to traumatic events. For health workers, EW represents an important support to prevent Compassion Fatigue and Burnout. As literature showed that Compassion Satisfaction, Group Cohesion and the Organizational Commitment are protective factors able to counter the onset of Compassion Fatigue and Burnout, the aim of this study is evaluating the effect of Expressive Writing protocol in Palliative Care workers on Compassion Satisfaction, Group Cohesion and Organizational Commitment. Methods: A quasi-experimental quantitative 2x2 prospective study was conducted with two groups and two measurements. 66 professionals were included. Outcome variables were measured using: Organizational Commitment Questionnaire, Compassion Satisfaction Rating Scale, ICONAS Questionnaire, Questionnaire for the evaluation of EW sessions. Results: The parametric analysis through Student t test did not show statistical significance within the experimental group and between the experimental and control groups. One significant difference in the pre-intervention assessment of Normative Commitment t (gl 64) = -2.008 for p< 0.05, higher in the control group, disappeared in the post intervention evaluation. An improvement trend in all variables within and between groups was present, with a positive assessment of utility from the participants. Conclusions: This intervention did not significantly impact outcome variables. It is however conceivable that by modifying the intervention methodology, it could prove effective. The positive evaluation by the operators, suggests to keep trying modelling a protocol tailored on Palliative Care professionals. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: Expressive Writing, Palliative Care Professionals, Compassion Satisfaction, organizational Commitment, Group Cohesion

1. Introduction

The healthcare professionals working in palliative care are daily exposed to emotionally intense situations both from the point of view of the work load and of the emotional weight that terminal patient care requires. The Palliative Care professionals work in teams to reach personalized outcomes based on the needs of the patient and his/her family members so as to accompany them in the critical phases of pathologies with poor prognosis and in the terminal phase of the disease.

The scientific literature suggests the Expressive Writing (EW; 1) is a valid tool for the adjustment of the person to traumatic events, and for the prevention of stress-related health problems, acting on the psycho-physical well-being of those who use it. The EW is an intervention aimed at processing stressful situations and difficult emotional episodes through the personal production of a text written in one or more sessions.

Studies conducted up to now using EW have shown satisfactory results: positive effects on mood (1), and on the immune system (2). Furthermore, EW protocols have proven effective on mild forms of depression (3), on anxiety (4), on eating disorders (5), on different types of post-traumatic stress (6), on stress and satisfaction in the workplace (7). In the healthcare context, the effectiveness of EW has been demonstrated in cancer patients for the reduction of emotional distress (8) and in patients affected by HIV (9).

A recent study carried out on health workers has shown that EW represents an important support to prevent and manage the effects of Compassion Fatigue (CF) and decrease the incidence of Burnout (BO) by improving the use of individual coping strategies (10). For CF we mean a psychological disorder commonly caused by the knowledge and closeness with the pain of others (11) while BO indicates a stress condition, referred to the operator who provides assistance, caused by uncontrollable factors present in the workplace and characterized by dissatisfaction towards the career, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization.

Studies have shown that CF and BO negatively affect the psycho-physical well-being and the performance of healthcare professionals in Palliative Care: past clinical experiences, physical exhaustion, the experience of a traumatic event, the discomfort towards colleagues, the emotional exhaustion, and social isolation, are all factors that determine the appearance of CF and BO (12).

Compassion Satisfaction (CS), Group Cohesion (GC) and the Organizational Commitment (OC) are the protective factors that are able to counter the onset of Compassion Fatigue and Burnout.

The CS includes the positive effects that an individual can derive from working with suffering people, including positive feelings with respect to helping others, contributing to the good of society and more generally the pleasure of “doing the job well”; in fact it turns out to be a protective factor for professionals who work in contact with death, but only if they have the right awareness and skills in dealing with these situations (13).

The Group Cohesion (GC) indicates the degree of union of the individual within a group, generating an influence and a positive interaction between the various members; the Organizational Commitment (OC) promotes a positive feeling that indicates the quality of the bond that the individual establishes with his / her own organization. These factors are able to moderate stress and its symptoms in the professional, enhancing adaptive coping strategies. Both the GC and the OC, are effective in decreasing the negative effects of Burnout and Compassion Fatigue, increasing instead the Compassion Satisfaction in the professionals (14)

It has been shown that in the healthcare staff the increase in CF and BO (negative factors) correspond to a decrease in CS (protective factor); these factors depend on the area in which the professional operates and on the characteristics of the work. Palliative care is, in fact, significantly involved in the negative relationship between CS and BO and CS and CF (14).

The tendency to develop adaptive coping strategies positively influences the CS and negatively influences the appearance of BO; from this it is clear that the professional who shows the greatest inclination to the development of effective coping strategies (above all spiritual reflection with regard to death and mourning) also matures preventive defense mechanisms against Burnout (15).

The effectiveness of Expressive Writing in contexts with a high level of emotional stress has been confirmed, but still we want to investigate whether its use by Palliative Care professionals can lead to an increase in protective factors such as Compassion Satisfaction, Group Cohesion and Organizational Commitment, thus bringing positive repercussions both for the professional and for the organization of the work structure, the management of costs and resources (16).

2. Aims

Primary aim: to evaluate the effect of the Expressive Writing protocol in Palliative Care workers on the levels of Compassion Satisfaction, Group Cohesion and Organizational Commitment.

Secondary aims: to evaluate the professionals’ perception of usefulness of the Expressive Writing protocol.

3. Methods

A quasi-experimental quantitative 2x2 prospective study was conducted with two groups (experimental group Expressive Writing / control group Neutral Writing) and two measurements: pre / post with a one-week interval (17).

3.1 Sample

A sample of 66 (10) participants was selected through a balanced sampling of convenience by setting. Palliative care professionals included: Nurses, Health Care Workers, Physicians, and Psychologists working at Palliative Care Operational Units (Hospice, territorial network services) in Northern Italy.

The participants met the following criteria:

- Fluently spoken and written Italian;

- Expressed willingness to participate in the study, after signing the informed consent;

- Working at least 24 hours a week without interruption for at least 6 months (18).

3.2 Instruments

To evaluate the effect of EW intervention on the selected variables (GC, OC, and CS), the following scales were used:

a) Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (19): composed of 25 items with a 6-point Likert scale response - from 1 = completely disagree to 6 = completely agreed - which merge into 3 corresponding independent subscales: Affective Commitment, which collects 10 items; Continuance Commitment, which collects 7 items; Normative Commitment, which collects 8 items.

b) Compassion Satisfaction Rating Scale taken from the Professional Quality Of Life Scale (13): composed of 10 items with a Likert scale response of 5 points from 1 (never) to 5 (very often); each participant must consider the statements regarding himself / herself and his / her current situation and select the answer that has been true in the last thirty days.

c) ICONAS Questionnaire (Organizational Climate Survey in Healthcare Facilities) for the assessment of the organizational climate within the Unit, composed of 15 items with a self-anchored scale (a continuum with two extreme values from 1 “Low / Low” to 10 “Very / High”);

d) Questionnaire for evaluating the usefulness of EW sessions: built ad hoc in order to evaluate the usefulness of writing in relation to the constructs investigated in a short time, in the last days after the first session. It consists of four questions:

1) How useful is the EW experience?

2) Have you felt relief after using EW in the last few days?

3) Did you feel uncomfortable using EW?

4) Would you advise someone to use EW?

For each question the participant is asked to place a cross on the item that identifies the perceived usefulness of the writing: not at all, a little, enough, a lot. This tool will be only used in the post-test phase with the participants who joined the EW group.

3.3 Procedure

The study was divided into two phases:

Phase 1:

An identification code was assigned to the participants and they were subdivided with block randomization into two groups: EW experimental group and Neutral Writing (NW) control group.

Phase 2:

Session 1: the participants of both groups completed a socio-demographic questionnaire and three scales for the evaluation of the outcome parameters. Subsequently each participant was given a writing mandate lasting 15 minutes based on the group to which he was assigned (EW vs NW).

Session 2: after a minimum interval of one day and a maximum of three days, the participants were invited to a second writing session, with the same mandate as the previous one.

Session 3: after a minimum interval of one day and a maximum of three days the same scales of session 1 were administered. The ad hoc questionnaire was also administered to the experimental group.

3.4 Expressing Writing Protocol

The core tools of this study are the EW and the NW. There are two writing sessions required for both groups; the first during the first administration of the socio-demographic questionnaire and the scales for assessing the outcomes; the second is requested after a minimum interval of one day and a maximum of three days. In the EW intervention, the participant was asked to write for 15 consecutive minutes about traumatic, stressful and emotionally significant events, concerning his own professional life. In the mandate of NW, used as a control tool, the subject was asked to describe in a more objective way an event that has occurred without dwelling on emotions, thoughts and feelings.

3.5 Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration (http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm).

The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Area Vasta Emilia Nord on 10.10.2018.

The study participants were informed in detail by the investigator on the aims and procedures of the study, and signed a specific informed consent to the study and processing of personal data, which was archived together with the study documentation.

4. Results

The data was collected and sorted using Excel and the statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 21 software.

66 participants were recruited, divided into 2 research groups: Expressive Writing (Expressive Writing, EW; N = 35) and Neutral Writing (Neutral Writing, NW; N = 31). Female participants constitute 68.2% while male 31.8%.

The age of the participants was divided into 4 clusters: 18-25 years, 26-35 years, 36-45 years, 46-65 years. The 34.8% of participants are in the 26-35 age cluster; the 62.1% of the sample is composed of nurses.

To verify the normal distribution of the collected data, Asymmetry and Kurtosis were calculated, which for these variables had an absolute value less than 1, thus confirming a distribution sufficiently compliant with the normality curve and justifying the use of parametric analyzes.

4.1 Baseline Evaluation

The Student’s t test for independent samples was applied to assess the presence of significant differences between the two groups in baseline. A statistically significant difference between the two groups occurred only with regard to the level of Normative Commitment t (gl 64) = -2.008 for p <0.05.

The EW group has an average base value of 20.37 while the NW group has a value of 24.13.

4.2 tTest within subjects EW

Having verified the normal distribution of the data, we applied the Student’s t test for paired samples for an analysis within the group in reference to the experimental group of EW.

From the analysis of EW group’s means no significant difference between PRE and POST emerged, although a slight tendency towards improvement was shown for the more strictly organizational variables, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean values PRE and POST EW intervention

| Affect.Comm | Cont. Comm. | Norm. Comm | Comp. Sat | ICONAS | |

| Mean (PRE) | 39,11 | 20,83 | 20,37 | 37,91 | 105,86 |

| Mean (POST) | 39,60 | 22,00 | 21,29 | 37,91 | 106,86 |

4.3 tTest between subjects EW/NW

For the analysis POST between groups we used the Student’s t test for independent samples. No significant differences were noted in the means of the two independent samples.

The means referring to the five variables investigated POST intervention in groups 1 (EW) and 2 (NW) are indicated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean values POST EW and NW

| Affect.Comm | Cont. Comm. | Norm. Comm | Comp.Sat | ICONAS | |

| Mean POST EW | 39,60 | 22 | 21,29 | 37,91 | 106,86 |

| Mean POST NW | 38,35 | 23,55 | 23,32 | 38,61 | 107,90 |

Following the intervention of EW the difference in the assessment scale of the Normative Commitment of the two groups (EW / NW) is no longer significant.

4.4 Multiple Regression

To investigate the effect of the independent variables on the dependent variables, a multiple stepwise backwards regression was carried out by inserting factors such as age, training and sex. Once the prerequisites were verified, the test showed that the only variable that affects one of the investigated constructs is age.

Age has a significant effect on Affective Commitment with R2 =, 16 for p =, 001; β =, 395 for p =, 001 (Table 3)

Table 3.

Effect of Age on AC

| Model | Std. Coefficients | t | Sign. | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | ||||

| 1 | (Constant) | 32,780 | 2,043 | 16,048 | 0,000 | |

| Age | 2,512 | 0,730 | 0,395 | 3,442 | 0,001 |

From the regression it emerges, therefore, that the age range of the respondents explains 16% of the variance of the Affective Commitment. In particular, carrying out multiple Bonferroni comparisons, a significant difference emerges between the group 2 (26-35 years) and group 4 (46-65 years), reposted in Table 4. The average difference is significant at the level 0.05.

Table 4.

Bonferroni test for mean differences

| AC | ||

| Bonferroni | ||

| (I) Age | Mean difference (I-J) | |

| 2 | 4 | -7,92* |

| 4 | 2 | 7,92* |

4.5 Subjective Evaluation EW

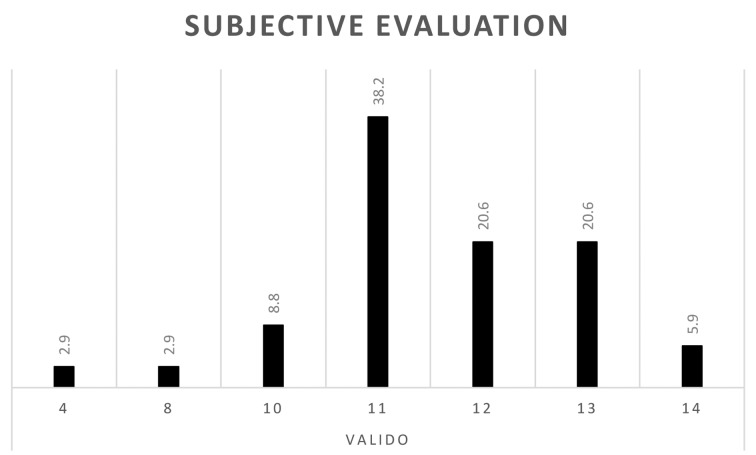

The subjective rating scale administered only to the participants of EW group has a minimum score of 4 and a maximum of 16. The 38.2% reported a score equal to 11 which indicates an almost positive evaluation of the intervention while 20,6% gave a score between 12 and 13. 5.9% gave a score of 14, evaluating the intervention of EW very positively. Only 2.9% of the sample reported a negative evaluation of the intervention with a score of 4. In the graph below the percentages based on the frequencies are reported (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of Subjective evaluation answers

5. Discussions

The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that a specific protocol of Expressive Writing, in contexts of high level of emotional stress as in Palliative Care professionals, could be effective in increasing the level of Compassion Satisfaction (CS), Group Cohesion (GC) and Organizational Commitment (OC), protective factors with respect to Compassion Fatigue (CF) and Burnout (BO).

The analysis within groups and between groups showed no significant difference between the pre and post writing intervention. This result, therefore, requires the confirmation of the null hypothesis: it is possible to state that the present research protocol did not produce a significant result on the variables examined.

However, the results concerning the subjective evaluation of the participants who experienced the EW protocol, had a mostly positive response, as they perceived the writing experience as useful, feeling relief after its use. In fact, only 2.9% of the sample reported a negative evaluation of the intervention with a score of 4.

The difference in the effect of the intervention on the organizational variables here examined with respect to the variables already examined in the literature, mainly of a strictly individual nature, is certainly evident. The method we used (20), was structured with two measurements and two intervention sessions, ie the participants were subjected to a first writing session, for 15 minutes consecutively, after completing the questionnaires in the baseline, and, at a minimum distance of 1 day and a maximum of 3 days, a second writing session. Then, at a distance of at least 1 day maximum 3 days, they were asked to complete the same post-intervention questionnaires to evaluate its effectiveness. It is conceivable that by exposing the sample to EW sessions that are more prolonged over time, the result about the benefit may be more significant. In the literature other studies have used different methods for the intervention, that is by performing 3 writing sessions and a follow-up one month from the last session (10). Also in this study it was asked to write continuously for 20 minutes for three consecutive days, obtaining a positive result with respect to the study hypothesis, namely that the EW positive impacts on adaptive coping strategies and perceived job satisfaction. Again, “Expressive writing to improve resilience to trauma: A clinical feasibility trial” (21), is a study in which 39 participants, who reported emotional or physical trauma in the previous year, received an intervention of 6-week expressive writing achieving positive results by increasing resilience and significantly decreasing participants’ stress and depressive symptoms. In another study, 96 participants also wrote on three occasions for three weeks, obtaining a positive result with a reduction in post-traumatic stress (22). Apparently the time between one writing session and another seems to be significant in order to have a positive impact on the person who uses it. As supported by the theory of Pennebaker, using intervals of a week between sessions, leads in any case an overall greater effect than at intervals of a day, as the best benefits seem to occur during the days following the writing session (17). With reference to the data obtained in this study, it is possible to hypothesize that the duration of this intervention was not sufficiently prolonged in time to obtain a statistically significant result. By carrying out writing sessions once a week, for several weeks (17), it would have been possible to hypothesize a clearly superior benefit compared to the investigated constructs.

From the analysis carried out by Student’s t on the values of the two populations in baseline, an interesting statistically significant difference emerged between the means of the Normative Committment of the EW group (20.37) and that of the NW group (24.13). It should be underlined also the presence of small variations between the two groups from pre to post intervention, in relation to the administration of EW.

It is possible to hypothesize that the EW intervention acted within the enlisted sample increasing the levels of Normative Commitment. It is therefore possible to hypothesize that a prolonged intervention time, could make this increase in the variables’ value a statistically significant datum.

Having this study an exploratory character with respect to the application of this methodology of intervention (EW) on organizational variables, and not having been previously addressed in the scientific literature, it is necessary to analyze in depth the probable reasons for which the hypothesis of the study was found to be null.

The constructs investigated may vary according to the setting in which the operator works. For example, the Organizational Commitment evaluates the cohesion of the work group and the serenity of the dynamics in the team; the Home Assistance contexts do not provide this variable as much as present and decisive as the Hospice context, as the professional on the territory is less in contact with colleagues compared to a department / structure. So we can assume that some professionals do not work in a context that justifies a change in this variable.

Another remark, in addition to the way in which the writing sessions were carried out, is the way in which the participants were told to face the writing mandate; this in fact did not provide for a specific episode, but rather indicated to tell in a free way experiences / facts about the working activity. It is therefore legitimate to ask whether, indicating to the participants to argue on a topic concerning teamwork, organizational support and difficulties, there would have been different results. In fact most of the participants, both the EW sample and the NW one, told of situations / experiences related to the patients care, not addressing issues related to the context and the team.

In addition to this, it is advisable to reflect on the professionals recruited during the study. The sample is in fact composed of nurses (about 62% of the total), Health Care Workers (31.8%) and Physicians (6.1%) with a clear absence of the Psychologist. The Psychologist is an essential figure in the Palliative Care team and therefore understanding his/her role in the study actually means completing the range of professionals enrolled.

The data that emerged following the Multiple Regression shows the effect of the age on the Affective Commitment. Performing the multiple Bonferroni comparisons, a significant difference emerged between the group 2 (age group 26-35) and group 4 (age group 46-65) in the Affective Commitment. We can therefore hypothesize that this datum may also be linked to the years of professional service; group 4 represents the participants who are over 46 years of age and the fact that this variable positively influences the AC leads to think that a greater seniority within the organization can increase the emotional participation towards the organizational structure. Seniority, referring to both age and years of service in the same organization, can be considered, therefore, a directly influential factor on these questionnaires. An important disparity between these age categories (group 2 - group 4), as we have just noted, can be given by the ability of the worker to integrate with the organization and with the work group, from the ability to know how to relate and organize based on also to the experience gained. This relationship, therefore, between age and Affective Commitment, assumes a clear importance in a preventive perspective, considering that studies have shown that both older employees and younger employees develop a pre-established and generalized opinion, and therefore not based on direct experience of particular events; however, older employees seem to be vulnerable to these episodes and therefore are predisposed to a disengagement within the work unit. For older employees working in an inadequate or poorly organized setting where it is difficult to reap benefits, would prove to be a negative factor on job satisfaction, commitment and well-being, thus making them even more favorable to leave the workplace. This is because they are less likely to assess these threats as a challenge, something that could happen in a younger employee, willing to get involved and assert their values but also the ethical and professional values that concern the healthcare organization for which they work (23).

6. Conclusions

The data collected in this study confirm the null hypothesis: the Expressive Writing intervention did not have a statistically significant effect on the Organizational Commitment, Compassion Satisfaction and Group Cohesion.

The slight tendency towards improvement in the variables and the positive evaluation expressed by the participants of the group subjected to the EW, pushes us to carefully consider the limits of the study in order to offer a trajectory of real improvement for the purposes of future research.

Among the limitations of the study we find the reduced number of variables identified in performing the study compared to those actually taken into consideration during the course of the study. For example, to assess the effectiveness of the intervention the number of years in which the operator works as a health professional and in palliative care could be taken into consideration. It is possible that, considering more variables, the outcomes may be different as data measurement and analysis could be expanded.

Another consideration emerges with respect to the protocol, as a different one could be foreseen, organizing it differently from the one here proposed: in a future study more specific indications could be given in the assignment of EW and NW, focusing and identifying better the mandate of the two groups. The EW mandate could refer to a specific event with high emotional intensity occurred in the professional context, repeatedly analyzed during the writing sessions, to encourage the development of feelings and emotions. Furthermore, the mandate of the NW control group could be formulated so that the participants do not talk about work experiences in palliative care. In fact this could lead the participant to tell of an emotionally significant event, although not required in the delivery.

The time taken for the study may not have been sufficient to carry out the collection of questionnaires and writings: probably a greater number of writing administrations would have had a more significant effect (compared to the two sessions proposed by this protocol) in order to obtain more reliable results. Furthermore, the possibility of carrying out a follow-up at a later date could make the study more significant.

Even the methods of administration may have influenced the participants: the discomfort given by the time limit, related to less freedom of expression of the story, must be taken into consideration. Some participants may have needed more time or more comfortable space to process the work and proceed with the writing session in order to free their thoughts.

Finally, not in order of importance, we would have needed to collect more data in order to carry out this research in the best possible way. The number of participants and the lack of proportionate representation of the professional figures operating in palliative care teams does not make it possible to analyze data that can be generalized on all health professionals.

Replicating the study with the proposed suggestions could increase the value of the scientific method adopted to investigate the variables taken into consideration: thanks to the possibility of being replicated, verified and increased, the results could lead to an increased level of generalizability. Therefore, although this study has not brought to light significant evidence of effectiveness of the EW protocol on the improvement of the organizational variables investigated, we consider it appropriate not to abandon the research on this topic, but take it back and improve it, going to create more specific and useful protocol for the support of professionals working daily in palliative care.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Pennebaker JW, Beall SK. Confronting a traumatic event: Toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. J Abnorm Psychol. 1986;95(3):274–281. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pennebaker JW, Kiecolt-Glaser J, Glaser R. Disclosure of traumas and immune function: health implications for psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(2):239–245. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frattaroli J. Experimental disclosure and its moderators: a meta analysis. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(6):823–865. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Emmerik AAP, Kamphuis JH, Emmelkamp PMG. Treating acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder with cognitive behavioral therapy or structured writing therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(2):93–100. doi: 10.1159/000112886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.East P, Startup H, Roberts C, Schmidt U. Expressive Writing and Eating Disorder Features: a preliminary trial in a student sample of the impact of three writing tasks on eating disorder symptoms and associated cognitive, affective and interpersonal factors. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2010;18(3):180–196. doi: 10.1002/erv.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoyt T, Yeater E. The effects of negative emotion and expressive writing on post traumatic stress symptoms. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2011;30(6):549–569. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadovnik A, Sumner K, Bragger J, Pastor SC. Effects of expressive writing about workplace on satisfaction, stress and well-being. J Acad Busin Econ. 2011;11(4):231–237. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallo I, Garrino L, Di Monte V. L’uso della scrittura espressiva nei percorsi di cura dei pazienti oncologici per la riduzione del distress emozionale: analisi della letteratura. Professioni Infermieristiche. 2015;68(1):29–36. doi: 10.7429/pi.2015.681029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Metaweh M, Ironson G, Barroso J. The Daily Lives of People With HIV Infection: A Qualitative Study of the Control Group in an Expressive Writing Intervention. Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2016;27(5):608–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonarelli A, Cosentino C, Artioli D, Borciani S, Camurri E, Colombo B, D’Errico A, Lelli L, Lodini L, Artioli G. (2017) Expressive writing. A tool to help health workers. Research project on the benefits of expressive writing. Acta Biomed. 2017;88(5):13–21. doi: 10.23750/abm.v88i5-S.6877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fingley C. R. New York, London: Routledge; 1995. Compassion Fatigue. Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in those who treat traumatized. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kase S, Waldman E, Weintraub A. A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study of Compassion Fatigue (CF), Burnout (BO), and Compassion Satisfaction (CS) in Pediatric Palliative Care (PPC) Providers (S704) J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(2):657–658. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stamm BH. Professional quality of life: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue version 5 (ProQOL) 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slocum-Gori S, Hemsworth D, Chan WW, Carson A, Kazanjian A. Understanding Compassion Satisfaction, Compassion Fatigue and Burnout: a survey of the hospice palliative care workforce. Palliat Med. 2013;27(2):172–8. doi: 10.1177/0269216311431311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sansó N, Galiana L, Oliver A, Pascual A, Sinclair S, Benito E. (2015) Palliative Care Professionals’ Inner Life: Exploring the Relationships Among Awareness, Self-Care, and Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue, Burnout, and Coping With Death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(2):200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houck D. Helping nurse cope with grief and compassion fatigue: an educational intervention. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013;18(4):454–458. doi: 10.1188/14.CJON.454-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smyth JM. Written emotional expression: effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(1):174–184. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur A, Sharma MP, Chaturvedi SK. (2018) Professional Quality of Life among Professional Care Providers at Cancer Palliative Care Centers in Bengaluru, India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24(2):167–172. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_31_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen NJ, Meyer JP. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization”. J Occup Psychol. 1990;63:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tonarelli A, Cosentino C, Artioli D, Borciani S, Camurri E, Colombo B, D’Errico A, Lelli L, Lodini L, Artioli G. Expressive writing. A tool to help health workers of palliative care. Acta Biomed. 2018;89(6):35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glass O, Dreusicke M, Evan J, Bechard E, Wolever RQ. Expressive Writing to improve resilience to trauma: A clinical Feasibility trial”. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019;34:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallagher MW, Long LJ, Tsai W, Stanton AL, Lu Q. The Unexpected impact of Expressive Writing on post-traumatic stress and growth in Chinese american creats cancer survivors. J Clin Psychol. 2018;74(10):1673–1686. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Von Hippel C, Kalokerinos EK, Haantera K, Zacher H. Age-based stereotype threat and work outcomes: Stress appraisals and rumination as mediators.”. Psychol Aging. 2019;30(1):68–84. doi: 10.1037/pag0000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]