Abstract

Background and aim: Pelvic ring fractures represent a challenge for orthopaedic surgeon. Their management depends on patient’s condition, pattern of fracture and associated injuries. Optimal timing for synthesis is not yet clear. The aim of this study was to define if surgical timing influenced clinic and radiographic outcomes following open reduction and internal fixation for Tile B and C fractures. Materials and methods: 38 patients were included. Patients underwent a clinical examination with the Majeed Score, Iowa Pelvic Score and Orlando Pelvic Score. The radiographic assessment was performed according to Matta Pelvic Score. A statistical analysis of the data compared patients who were operated within 3 weeks (group 1) and those operated later (group 2). Results: Both clinical and radiological outcomes were influenced by timing of surgery. Conclusion: Pelvic ring fractures interest many polytrauma patients and, therefore, their surgical orthopedic approach is frequently delayed as consequence of the severity of the associated clinical conditions. An early surgery of pelvic rong fractures allows a better quality of reduction and osteosynthesis. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: pelvis, fracture, injury, timing, fixation, surgery

Introduction

Pelvic ring fractures (PRFs) are rare injuries which occur with a frequency of approximately 20-37 per 100.000 population (1,2) and represent up to 6% of all fractures (3-5).

PRFs are often caused by high energy traumas, such as road traffic accidents (50%), work accidents (30%) and falls from high (15%). They are described in up to 20% of polytrauma patients and are associated with high mortality and severe morbidity; mortality in fact ranges from 8% to 32% and it is mostly caused by vascular (50%) and urinary injuries (30 %) (7).

Up to 22% of all pelvic fractures are hemodynamically unstable and for this reason their treatment requires a multidisciplinary team approach including the general, vascular and orthopedic surgeon, anesthesiologist and interventional radiologist (8-10), which together have to manage injuries of different districts.

Consequently, orthopedic definitive treatment is often delayed. Optimal timing for fixation is not yet clear but recent guidelines suggest that open reduction and internal synthesis within 21 days is associated with a higher percentage of excellent reductions and better long-term results (11).

The aim of this study was to define if surgical timing influenced clinic and radiographic outcomes following open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) for Tile B and C fractures (12-15).

Materials and methods

Patients who underwent ORIF for Tile B and C PRFs between January 2010 and January 2018 were included in this retrospective trial with a minimum follow-up of 1 year. Each case was identified from an information database at the University Hospital of Parma. Patients in whom charts or radiographs were unavailable or incomplete were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were open fractures and concomitant acetabulum or columns fractures.

Age, gender, mechanism of injury (low/high energy trauma), fracture classification according to Tile and surgical characteristics (quality of reduction and surgical timing) were extracted from the database and registered.

A functional evaluation of all subjects was performed at follow-up (mean 4.3 years; min. 1 and max. 9) through the Majeed Pelvic, Iowa Pelvic and Orlando Clinic Pelvic Score (16-18).

A radiological analysis was done by an indipendent observer (ML) using antero-posterior, inlet and outlet views performed immediately after surgery and at follow-up. Each radiograph was assessed according to Matta Pelvic Score in order to classify the quality of reduction (19).

All data were entered into a database (Microsoft Excel). Descriptive statistics (mean, percentage and ranges) were calculated. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the two groups. Statistical analysis was undertaken using SPSS for Windows. Statistical significance was defined as p value of <0.05.

Results

Thirty-eight patients respected the inclusion criteria and all underwent to ORIF. Twenty out of 38 (group 1) were operated within 21 days from trauma and 18 were surgically treated later (group 2).

In group 1 6 (30%) were females and 14 (70%) males and in the second group 3 (16.7%) were females and 15 (83.3%) males. The mean age at the time of injury was 40 years in group A (25-60) and 42 in group B (30-61). An high energy trauma was described in 75% of cases in group 1 and in 82% of group 2.

In group 1 the mean time between injury and surgery was 10 days (min. 5 max. 20) and in the second group was 24 days (min. 21 max. 30).

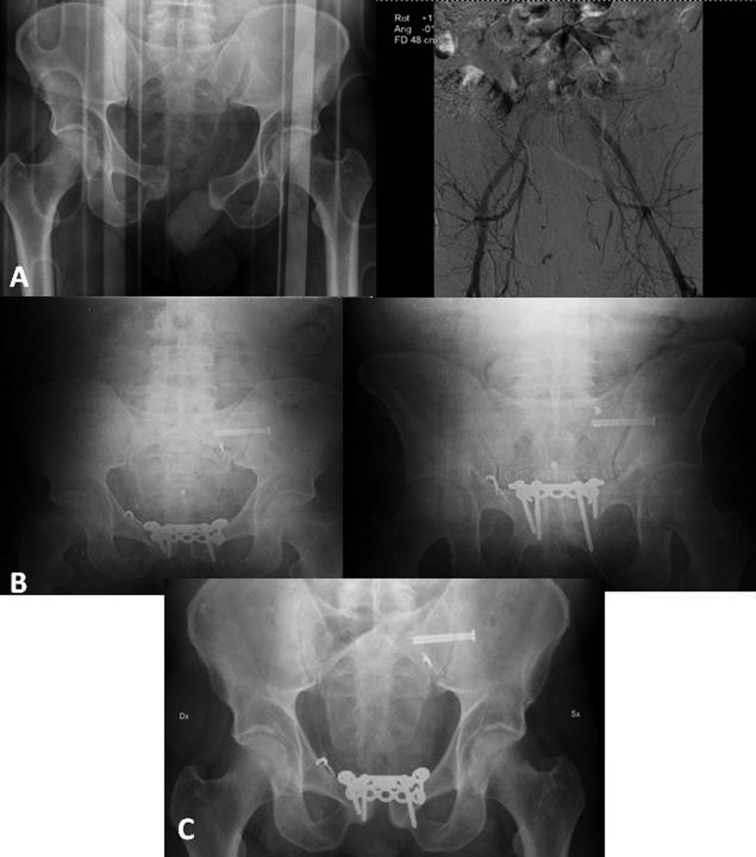

In group 1, 15 patients had Tile B1 fracture (Figure 1), 1 Tile B 2 and 4 Tile C1; in group 2 10 fractures were Tile B1, 1 Tile B2 and 7 Tile C1 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Tile B1 PRF in a patient of group 1. A; preoperative x-rays. B; postoperative radiographs with anatomical reduction. C; x-rays 2 years after trauma with the same quality of reduction

Figure 2.

Tile C1 PRF in a patient of group 2. A; preoperative x-ray and arteriography for embolization of the sacral branch of the left hypogastric and of the right epigastric artery. B; postoperative radiographs considered imperfect according to Matta Pelvic Criteria. C; x-ray 1 year after trauma

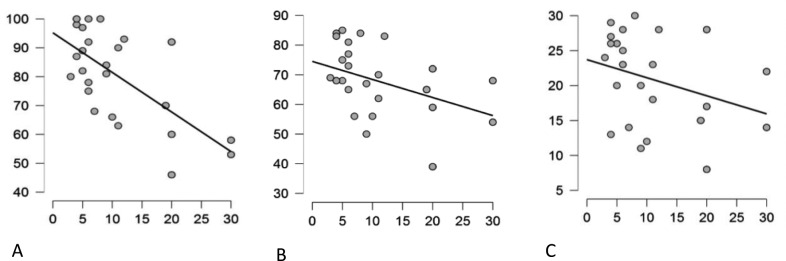

In group 1 the average Majeed Pelvic Score was 86/100, the average Iowa Pelvic Score was 71/90 and the mean Orlando Pelvic Score was 22.3/30. In group 2 these results were respectively 63.17/100, 59.50/90 and 17.33/30. There was a statistically significant difference among the two groups for all the scores (p=0.002, p=0,004, p=0,032) (Figure 3A, 3B, 3C).

Figure 3.

A. Majeed Pelvic Score. B. Iowa Pelvic Score. C. Orlando Clinic Pelvic Score. Distribution of the scores in relationship to timing of surgery. Better clinical results are observed in early surgery.

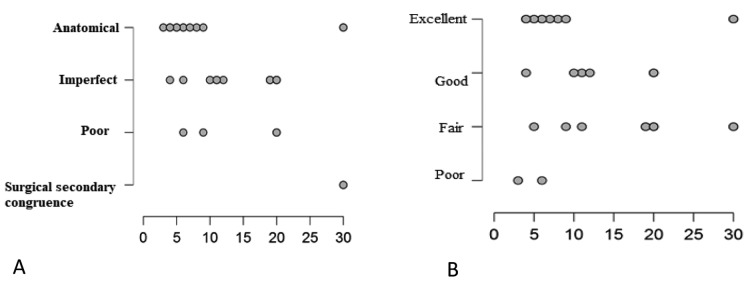

Radiological evaluation was in line with the clinical results and showed better reduction in group 1 (70% of cases with anatomic or excellent reduction) compared to group 2 (40% of cases with anatomic or excellent reduction) (p=0.047). This situation was similar immediately after surgery and at follow-up (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Postoperative (A) and at follow-up (B) radiographic evaluation. Similar distribution in A and B; better results in early surgery

Discussion

PRFs occur mainly in polytrauma patients and their presentation can be critical given the association with high energy traumas, haemodynamic instability and life threatening injuries.

Mortality, which is caused mainly by vascular and urinary injuries, is reported in up to 32% of cases (7) and those which require resuscitation are described in up to 25% of subjects (8-10). For this reason the best management of such injuries is based on a multidisciplinary approach which includes general, vascular and orthopedic surgeon, anesthesiologist and interventional radiologist, which together have to treat injuries of different districts.

In the past the majority of PRFs were managed non operatively. In Tile A lesions conservative treatment was associated to satisfactory results (20-22). This is not valid in Tile B and C patterns (23-26). Multiple studies in fact have shown the persistence of pain and reduced function in patients with residual deformity of the posterior pelvic ring greater than 1 cm (23,26) and poorer functional outcomes. For these reasons ORIF is the treatment of choice in the majority of these more severe injuries. A systematic review by Papakostidis et al. (23) found that Tile B and C PRFs treated with operative fixation had a higher union rate and a better quality of reduction that nonoperatively managed fractures. Gait disturbance was also found to be more common in nonoperatively managed cases. So a definitive fixation is necessary, and should be performed early.

The definition of the length in time of that early period is really difficult and optimal timing of synthesis is not yet clear. The definitive pelvic fixation is necessarily often delayed and it depends on the response to resuscitation, the type of associated injuries and the immune-inflammatory status of the patient. Recent evidences suggest to treat PRFs almost within 3 weeks from trauma (11). This timing facilitates reduction and stabilization of the fractures, thus guaranteeing better long-term outcomes (11).

This study confirms these assumptions. In fact, better clinical and radiological results have been observed in those patients in which fixation was performed within 21 days from trauma.

Conclusions

The results observed in the present study underline that an early orthopedic surgical treatment in PRFs guarantees better clinical and radiographic evolution. Associated severe clinical conditions can delay the definitive pelvic fixation which should be performed within 3 weeks from trauma.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Melton L, Sampson J, Morrey B, Ilstrup D. Epidemiologic features of pelvic fractures. Clin. Orthop. 1981;155:43–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ragnarsson B, Jacobsson B. Epidemiology of pelvic ractures in a Swedish county. Acta Orthop Stand. 1992;63(3):297–300. doi: 10.3109/17453679209154786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malgaigne J. Paris: J. B. Balliere; 1847. Traites des fractures et des luxations. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mucha P, Fame M. Analysis of pelvic fracture management. J. Trauma. 1984;24(5):379–86. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198405000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt A. Diagnostik, Therapie und Spatfolgen bei Beckenfrakturen. Mschr. Unfallheilk. 1974;77:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giannoudis PV. Prevalence of pelvic fractures, associated injuries, and mortality: the United Kingdom perspective. J Trauma. 2007;63:875–83. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000242259.67486.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balogh Z. The epidemiology of pelvic ring fractures a population based study. J Trauma. 2007;63:1066–73. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181589fa4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong JM. Fractures of pelvic ring. Injury. 2017;48:795–802. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lunsjo K. Associated injuries and not fracture instability predict mortality in pelvic fractures: a prospective study of 100 patients. J Trauma. 2007;62:687–91. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000203591.96003.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauschild O. Mortality in patients with pelvic fractures: results from the German pelvic injury register. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2008;64(2):449–55. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31815982b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matta M, Tornetta P., 3rd Internal Fixation of unstable Pelvic Ring. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1996;329:129–40. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosch U, Pohlemann T, Tscherne H. Primary management of pelvic injuries. Orthopade. 1992;21(3):85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Browner D, Cole JD, Graham JM, Bondurant FJ, Nunchuck-Burns SK, Colter HB. Delayed posterior internal fixation of unstable pelvic fractures. J Trauma. 1987;27(9):998–1006. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198709000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bucholz R. The pathologic anatomy of Malgaigne fracture-dislocations of the pelvis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63A:400–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin S, Tomàs P. Pelvic ring injuries. Cas Lek Cesk. 2011;150(8):433–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Majeed SA. Grading the outcome of pelvic fractures. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1989;71:304–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.71B2.2925751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Templeman D, Goulet J, Duwelius PJ, Olson S, Davidson M. Internal fixation of displaced fractures of the sacrum. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1996;329:180–5. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole JD, Blum DA, Ansel LJ. Outcome after fixation of unstable posterior pelvic ring injuries. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1996;329:160–79. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matta JM, Mehne DK, Roffi R. Fractures of the acetabulum. Early results ofa prospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;205:241–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pogliacomi F, Costantino C, Pedrini MF, Pourjafar S, De Filippo M, Ceccarelli F. Anterior groin pain in athlete as consequence of bone diseases: aetiopathogenensis, diagnosis and principles of treatment. Medicina dello Sport. 2014;67(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pogliacomi F, Calderazzi F, Paterlini M, Pompili M, Ceccarelli F. Anterior iliac spines fractures in the adolescent athlete: surgical or conservative treatment. Medicina dello Sport. 2013;66(2):231–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calderazzi F, Nosenzo A, Galavotti C, Menozzi M, Pogliacomi F, Ceccarelli F. Apophyseal avulsion fractures of the pelvis. A review. Acta Biomed. 2018;89(4):470–6. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i4.7632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papakostidis C, Kanakaris NK, Kontakis G, Giannoudis PV. Pelvic ring disruptions: treatment modalities and analysis of outcomes. Int Orthop. 2009;33:329–38. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0555-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bucknill TM, Blackburne JS. Fracture – dislocations of the sacrum. J Bone Joint Surg. 1976;58-B(4):467–70. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.58B4.1018033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson RC. The long-term results of non-operatively treated major pelvic disruptions. J Orthop Trauma. 1989;3(10):41–7. doi: 10.1097/00005131-198903010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLaren AC, Rorabeck CH, Halpenny J. Long-term pain and disability in relation to residual deformity after displaced pelvic ring fractures. Can J Surg. 1990;33(6):492–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]