Abstract

Background and aim of the work: The rectus-adductor syndrome is a common cause of groin pain. In literature the adductor longus is reported as the most frequent site of injury so that the syndrome can be fitted into the adductor related groin pain (ARGP) group. The aim of this study was to define what is the best treatment between surgical and conservative in athletes affected by ARGP in terms of healing and return to play (RTP) time. Methods: A systematic review was performed searching for articles describing studies on RTP time for surgical or conservative interventions for ARGP. A qualitative synthesis was performed. Only 10 out 7607 articles were included in this systematic review. An exploratory meta-analysis was carried out. Due to high heterogeneity of the included studies, raw means of surgery and conservative treatment groups were pooled separately. A random effects model was used. Results: The results showed quicker RTP time for surgery when pooled raw means were compared to conservative treatments: 11,23 weeks (CI 95%, 8.18,14.28, p<0.0001, I^2=99%) vs 14,9 weeks (CI 95%, 13.05,16.76, p<0.0001, I^2 = 77%). The pooled results showed high statistical heterogeneity (I^2), especially in the surgical group. Conclusions: Surgical interventions are associated with quicker RTP time in athletes affected by ARGP, but due to the high heterogeneity of the available studies and the lack of dedicated RCTs this topic needs to be investigated with dedicated high quality RCT studies. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: rectus-adductor syndrome, groin pain, athletes, return to play

Introduction

Groin pain is an ambiguous clinical entity (1-5). The topic itself is still debated, with great lack of consent especially regarding the classification and therapeutic approach (6,7). Because of multiple definitions that are reported in literature (mostly improperly used) a terminological clarification seems to be necessary.

Groin pain is defined as an algic sensation in the groin area, which can underlie different pathologies, not necessarily musculoskeletal-related and sometimes in association (8). The pain is usually unilateral and localized to the pubic tubercle or to the medial compartment of the thigh, eventually irradiated to the adductor or abdominal muscles, to the pelvic floor and the genital area thus making the diagnostic process very difficult (8-10).

The rectus-adductor syndrome is one of the major causes of groin pain and it can be defined as the insertional tendinopathy of rectus abdominis and/or the adductors of the thigh and eventually associated with pubic osteoartropathy (8). The syndrome is typical of male athletes between 20 and 30 years of age which are involved in high intensity team sport, such as soccer, hockey, basketball and football (9,11,12). It is reported to have an incidence between 2,5-3% of all the sport related pathologies (13,14). The etiopathogenesis seems to be linked both to the imbalanced contraction of the two main dynamic stabilizers of the anterior pelvic area - the so-called muscle imbalance syndrome of the groin - and microtraumas associated to functional overuse of the same muscles: the rectus abdominis and the adductors of the thigh (15-19). Besides, the adductor longus is reported as the most frequent site of injury in several articles (20-22) which highlighted that the susceptibility of this muscle to injury can be traced to his peculiar anatomy and vascular supply from the deep femoris artery. Taking into account the systematic video analysis conducted by Serner et al. (23) on a series of acute adductor longus injuries in soccer players, most of them were non-contact, and extremely heterogeneous in term of pathogenesis, including both close and open chain actions such as change of direction, kicking, reaching the ball and jumping. According to the authors, the fast activation of the adductor longus in occasion of muscle lengthening seems to be a major mechanism of injury.

The recent work by Schilders et al. (24) proposed an alternative anatomic concept, trough the demonstration of a direct connection between pyramidalis and adductor longus muscle, renamed by the authors “pyramidalis-anterior pubic ligament-adductor longus complex”. The systematic dissection of 7 male cadavers showed that the rectus abdominis is not attached to the adductor longus, reducing its role in acute adductor longus injury. These findings may have future implication into the diagnostic and therapeutic management of the adductor longus acute strain.

Although frequently reported in literature, Sports Hernia and Athletic Pubalgia are both two misleading terms (6,25,26).

Sports Hernia (or Sportman’s Hernia) is referred to an occult hernia caused by weakness or tear of the posterior inguinal wall leading to groin pain in occasion of training and competition, not interfering with every day life (25).

Athletic Pubalgia is an extremely generic term that interests multiple pattern of injury such as the deficiency of the posterior abdominal wall/inguinal floor (Sports Hernia), the rectus tendon /rectus-adductor aponeurosis complex strain or tear and the inguinal and/or genital neuropathies (9).

Several authors proposed to move away from the use of both these terms, since their lack of specificity about the underling pathology and the anatomical site of injury: a new standardized and more organ-specific classification seems to be needed (6,15).

A deep effort to set up an unified classification system for groin pain was taken in the “Doha agreement meeting on terminology and definition in groin pain in athletes” with the proposal of a new classification focused on the anatomical site of injury and clinical findings (6).

Following this statement, the rectus adductor syndrome seems to be more properly included in the ARGP group since the major involvement of the adductors of the thigh with pain and tenderness.

The diagnostic process is based on an accurate history-taking, the clinical evaluation and instrumental investigations, which allow the morphological description of the injury (26-27).

The Italian Consensus, suggested to use a group of specific tests for adductor, abdominal wall muscle and hip joint in order to evaluate the tenderness of the involved structures (28,29).

The instrumental investigation mainly relies on conventional radiography, ultrasonography and MRI which is considered the gold standard exam for soft tissue evaluation and it allows to detect the presence of peculiar markers (30-32).

The therapeutic management of ARGP is challenging and it is usually conservative at first. It requires a multidisciplinary approach including rest, physical exercise, shock wave therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and platelet rich plasma eco-guided injections, eventually in association (26,33-35).

In case of failure of conservative management and significant limitation of the athletic performance, surgery may be considered (9). It usually consists of adductor tenotomy and/or reinforcement of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal; many techniques are described in literature (36-52).

Postoperative rehabilitation needs to be gradually progressive and focused on muscle strengthening, balance and flexibility (9).

The aim of this study was to define what is the best treatment between surgical and conservative in athletes affected by groin pain and in particular ARGP syndrome in terms of healing and return to play (RTP) time.

Materials and methods

In order to compare RTP time between surgical and conservative interventions in the treatment of ARGP syndrome in athletes, a selective systematic review of the literature was performed using PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar and CINHAL searching for specific articles. All mentioned databases were screened up to 30th April 2019.

The PRISMA (53) statement was followed for this systematic review and meta-analysis.

The following list summarized the applied PICOS criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies both in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

P (Population): Athletes with groin pain;

I (Intervention): All types of conservative or surgical intervention on adductor muscles;

C (Comparison): All types of control/comparison, even no control/comparison;

O (Outcomes): RTP time;

S (Study design): Randomized controlled trials (RCT), non-randomized clinical trials and prospective cohort studies.

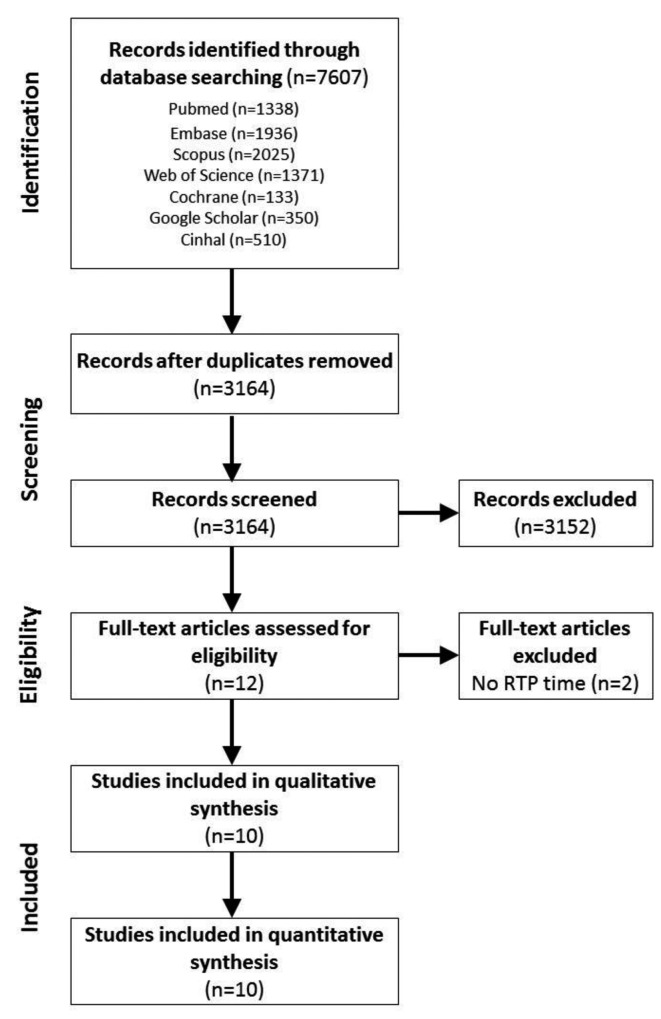

After searching electronic databases, 7607 articles were identified and collected. When duplicates were removed, 3163 articles remained for the screening process. After an evaluation based on the assessment of their contents, 3152 articles were excluded. Then, only 12 articles underwent full-text screening and 2 of them were excluded because of no RTP time was reported. Finally, 10 articles were included both in the qualitative and quantitative synthesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the systematic review and meta-analysis

Results were screened by three authors (PG, PB, ML). Data were manually extracted by a single investigator (PG) from included articles and then summarized in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review

| First Author and date | Study design | Number of patients, sex | Sport | Intervention | Group 1 | Group 2 | RTPt (weeks) | Authors’ conclusions | JS |

| 1) Holmich et al. 1999 | RCT | 68 M | Soccer 54 NR 14 | 1) Holmich Protocol. 3 times per week for 8-12 weeks. Patients were allowed to ride a bicycle. After the first 6 weeks of treatment patients were allowed to jog in running shoes on a flat surface so long as it did not provoke groin pain. 2)Laser treatment with gallium aluminium arsen laser 1’. Stretching of adductor muscles, hamstring muscles, and hip flexors. 30’’ per muscle, 3 times. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for 30 min at painful area. |

Intervention 1 30/34 | Intervention 2 29/34 | 23/30 18,5 4/29 18,5 | Y | 3 |

| Weir et al 2011 | RCT | 53 M | Soccer 37 Rugby 3 Running 3 Hockey 3 Speed skating 2 Squash 2 Tennis 1 Basketball 1 Handball 1 Track-and-fiel1 |

1) Holmich Protocol. 3 times per week for at least 8 weeks. During the first six weeks only cycling was allowed. At six weeks the return to running program was started. 2) Heat with paraffin packs for 10’, manual therapy. Slow jogging or cycling for 5’. Stretches of the adductors of both legs for 30’’. Warm bath for 10’. After 14 days of stretching if no pain or discomfort was felt, same return to running program as in group1 was performed. |

Intervention 1 22/25 | Intervention 2 26/29 | 12/22 17.3±4.4 13/26 12.8±6 |

N | 2 |

| Dojcinovic et al. 2012 | NRS | 99 M | Soccer 79 NR 20 |

1) Shouldice technique, ilioinguinal nerve neurolisys and resection of the genital branch of genitofemoral nerve. 2) Complete bilateral adductor longus tenotomy. |

Intervention 1 70/99 | Intervention 1+2 29/99 | 24/29 13,4 (12-16) 5/29 11,6 (10-15) 70/99 4.23 (3-16) |

U | 5 |

| Gore et al. 2018 | NRS | 64 M | Soccer 6 Gaelic Football46 Hurling 7 Rugby 5 NR 1 |

3-level rehabilitation program focused on inter-segmental control. | Intervento 64/64 | Controllo: 50 M non infortunati | 64/64 9,14 5.14-29.0 | U | 6 |

| Harr et al. 2017 | NRS | 20 M 2F | NR 7 Running 7 Lacrosse 3 Football 1 Baseball 1 Triathlon 1 Track-and- field 1 Horse riding 1 |

Suture herniorrhaphy with adductor longus tenotomy. | Intervention 22/22 | 22/22 6-8 | Y | 4 | |

| King et al. 2016 | NRS | 205 M | Gaelic football 131 Hurling 29 Soccer 25 Rugby 15 Hockey 5 |

3-level rehabilitation program focused on inter-segmental control. | Intervento 163/205 | 150/163 9.9±3.4 |

Y | 7 | |

| Sebecic et al. 2014 | NRS | 113 M 1 F |

Soccer 91 NR 23 |

1) Modified Shouldice technique, ilioinguinal nerve neurolisys and resection of the genital branch of genitofemoral nerve. 2) Bilateral adductor longus tenotomy. |

Intervention 1 83/114 | Intervention 1+2 31/114 | 81/83 4,4 (3-16) 31/31 11,8 (10-15) |

Y | 3 |

| Van der Donckt et al. 2003 | NRS | 41 M | Soccer 35 Running 3 Basketball 1 Ciclyng 1 Refereeing 1 |

1) Bassini’s hernial repair with unilateral percutaneous adductor longus tenotomy. 2) Bassini’s hernial repair with bilateral percutaneous adductor longus tenotomy. |

Intervention 1 27/41 | Intervention 2 14/41 | 41/41 27,6 (24-60) | Y | 5 |

| Yousefzadeh et al. 2018 | NRS | 17 M | NR 17 | Holmich protocol. 3 times per week for 8-12 weeks. Patients were allowed to ride a bicycle. After the first 6 weeks of treatment patients were allowed to jog in running shoes on a flat surface so long as it did not provoke groin pain. | Intervention 14/17 | 11/14 14.2 (10-20) | Y | 8 | |

| Yousefzadeh et al. 2018 | NRS | 18 M | NR18 | Modified Holmich protocol, focused on “core stability”, “elastiband”. Stadardized running programm for 10 weeks. | Intervention 15/18 | 13/15 12.06±3.41 |

Y | 8 |

Abbreviation: RTPt: return to play time; JS: Jadad Score; NR: not reported; RCT: randomized controlled trial; NRS: non randomized trial; M: male; F: female; Y: intervention is effective; N: intervention is not effective; U: it is unclear whether intervention is effective or not

The quality of the included randomized controlled trials (RCT) was assessed following the JADAD score dedicated tools (54). The quality of the included non-randomized trials was assessed following the criteria of the NIH dedicated tools (55). Due to high heterogeneity of the included studies, raw means of surgery and conservative treatment groups were pooled separately. When mean standard deviations (SD) were not reported, they were estimated from reported or standard errors with proper statistical tools (56-57). When only sample medians, as well as minimum and maximum values, first and third quartiles were available, sample means and standard deviations were calculated with validated formulas accepting the assumption that the original data distribution was normal in order to maximize retrievable data and minimize publication bias (58). Considering high heterogeneity of included studies, a random-effect model was adopted to better estimate overall size effects.

Only 10 out 7607 articles screened were included in the systematic review. Data collected were summarized in table 2 and discussed to obtain a qualitative synthesis. An exploratory meta-analysis was carried out using Rstudio software (V.1.2.1335) as a semi-quantitative analysis. Included studies were heterogeneous in terms of design, population, intervention and comparison, so it was necessary to consider the different groups of interventions as separated observational prospective studies, in order to achieve the best possible homogeneity. Two meta-analysis for surgical treatment and conservative treatment were then performed.

I2 was used as a measure of consistency. I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were interpreted as representing small, moderate and high levels of heterogeneity.

Results

Of the reviewed studies 2 were RCTs and 8 were NRSs. Among the NRSs, 2 were clinical trials and 6 were prospective.

The total number of athletes included was 703. Of these, 4 (0.56%) were female (30,60,1) and the remaining 699 (99.44%) male.

The basic pathology was called “athletic groin pain/athletic pubalgia” in 3 studies (62-64) and in 4 “adductor-related groin pain”. Dojcinovic et al. (37), Harr et al. (30) and Sebecic et al. (1), referred to the pathology as sports hernia and/or adductory tendinopathy. In particular in the study by Harr et al. (30) reference was made to the aetiological sharing of the rectus abdominis muscle.

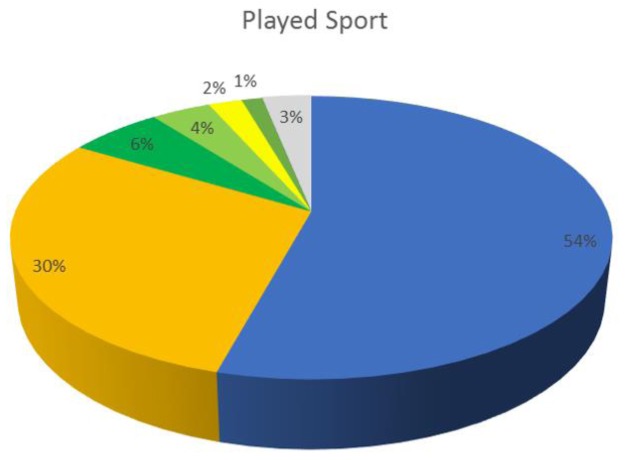

The most practiced sport was football (327 athletes-46.5%), followed by Gaelic football (177-25.17%), hurling (36-5.12%), rugby (23-3.27%), the race (13-1.84%), hockey (8-1.13%) and lacrosse (3-0.42%). Ice speed skating, athletics, squash and basketball accounted for 0.28% each. Other sports (baseball, cycling, horseback riding, football, handball, tennis, triathlon and refereeing) together made up 1.13%. For 100 athletes (14.22%) the sport practiced was not specified.

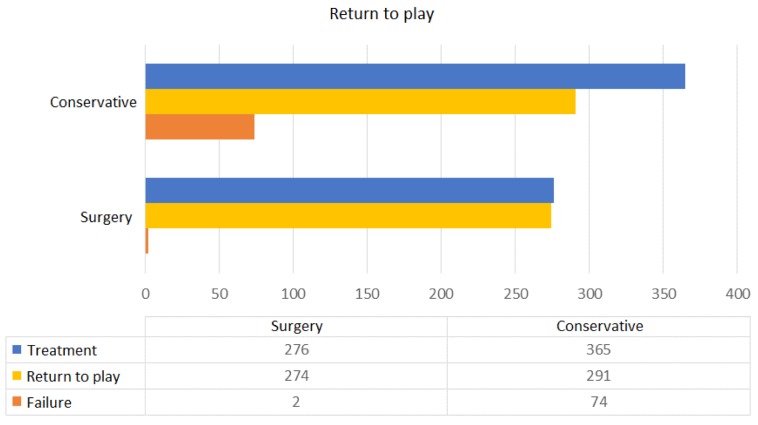

Two-hundred and seventy-six athletes underwent surgery and 274 (99.01%) returned to sport. Three-hundred and sixty-five athletes completed a conservative treatment program. Two-hundred and ninety-one (79.72%) returned to sporting practice. Sixty-two athletes (8.81%), whose totality belongs to the conservative treatment group, were excluded from the studies (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Graphic referred to intervention, return to sport and therapeutic failure of surgical and conservative treatment in the study population.

Blue = intervention (276 surgical; 364 conservative); Yellow = return to sport (274 surgical; 291 conservative); Orange = failure (2 surgical; 74 conservative)

In 4 studies (30,1,37,62) the treatment was surgical. In all 4, in at least one intervention group, the adductor tenotomy was performed along with an abdominal wall repair technique. In 2 reports (1,37) the abdominal wall repair technique was performed exclusively in an intervention group. No tenotomy of the long isolated adductor alone was performed in any study.

The approach to tenotomy was open in 3 studies and percutaneous in one (62). The tenotomy was bilateral in 3 reports (1,37,62), unilateral in one (62) and in one (30) it was not specified.

The tenotomy was complete in 2 studies (1,37), partial in one (30) and in one (62) it was not specified.

Abdominal wall repair was performed with an open approach and without the use of mesh in all studies. The techniques used were hernioplasty according to Bassini simple or modified (63), or according to Shouldice (1,37) and the herniorrhaphy with suture of the defects of the external oblique and of the joint tendon fascia, previously released, with the ileopubic tract (30).

In two studies (1,37) neurolysis of the ileoinguinal nerve and resection of the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve was associated.

Treatment was conservative in 6 studies. In all of these, in at least one intervention group, a training protocol was applied: in 3 Holmich protocol (35,60) and in the study by Yousefzadeh et al. (61) a variant thereof were done. In two reports, a training program focused on intersegmental control was planned (63,64).

Weir et al. (33) also added a standardized running program to the original Holmich protocol. This program was organized in 3 levels: slow travel, straight line shots and changes of direction.

The training program performed by Gore et al. (63) and by King et al. (64) was also divided into three levels. The first level included exercises of strength and intersegmental control. The linear stroke rehabilitation followed. The last level included exercises with changes of direction and the reacquisition of the ability to shoot at maximum intensity.

In 2 studies (59,60) a multimodal rehabilitation approach not focused on active exercise was evaluated in an intervention group.

Exercise protocols were supervised by physiotherapists in 3 cases (59,61,62). In 2 articles (60,64) there was no supervision during the training program and in one (65) it was not specified.

Referring to the conclusions, in 7 reports (30,33,35,62,64) the respective authors considered the intervention effective, in 2 (37,63) the judgment was not clear and in one (60) the intervention was not considered effective.

The analyzed studies were characterized by high heterogeneity. It was therefore decided to perform a meta-analysis of proportions with the raw averages of the RTP time isolating the groups investigating the surgical or conservative treatment for the adductory component only between RCT and NRS. This allowed the semi-quantitative evaluation of the two approaches to assess which would guarantee shorter timescales for the return to competitive activity.

It’s interesting to note, as two (62,64) among the mentioned studies, constituted the outliers of quantitative analysis so they were excluded.

From the meta-analysis of the studies investigating a conservative treatment a RTP average time of 14,91 weeks was observed(CI 95%, 13.05,16.76, p<0.0001, I^2 = 77%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot referred to the meta-analysis about mean RTP time (in weeks) after surgery. Description: groups of intervention are reported in columns with author first name. Means and standard deviations are reported in columns and a random-effect model was adopted to better estimate overall size effects

Referring to surgical treatment the result showed a RTP average time of 11,23 weeks (CI 95%, 8.18,14.28, p<0.0001, I^2=99%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot referred to the meta-analysis about mean RTP time (in weeks) for conservative treatment. Description: groups of intervention are reported in columns with author first name. Means and standard deviations are reported in columns and a random-effect model was adopted to better estimate overall size effects.

The qualitative synthesis seemed to highlight a more frequent return to sporting activity in subjects undergoing surgical treatment. However it was good to reduce the appropriateness and outcome of intervention considering that in 3 articles (62-64) the precise aetiology of “athletic groin pain” was not specified.

Quantitative synthesis suggested the superiority of surgical treatment over conservative in ensuring a faster return to sporting activity. The average RTP time of surgery was 11.23 weeks, compared to 14.9 weeks of conservative treatment.

Discussion and conclusions

Hip and pelvic lesions which determine groin pain are not infrequent and are often a challenge to manage, even for the most expert physicians.

Groin pain is the term commonly used to identify painful symptoms of the pubis and of the anterior pelvis, with possible irradiation towards the adductor, abdominal muscles and crural arches. These symptoms cannot be considered a pathology; it would be more correct to speak of “groin pain related syndromes”, that too often are simplistically and erroneously labelled “generic pubalgia”. In literature there is not a definitive accordance on approach for groin pain, which is universally recognized, thus increasing misdiagnosis and incorrect treatments. This is confirmed in this review in which only few (n=10) reports have the characteristics of valid scientific studies.

Consequently, also in recent years many athletes, both professional and non-professional, have had to interrupt their career or sporting activity prematurely for an imprecise pain to the groin or pubis which was not adequately diagnosed and treated. In the past it was very frequent to encounter these symptoms in high-level athletes at the end of their career; now, however, athletes of all ages, even adolescents, are being affected.

The rectus-adductor syndrome is one of the major causes of groin pain and it can be considered an insertional tendinopathy of rectus abdominis and/or the adductors of the thigh, more or less associated with pubic osteoarthropathy. Recently, Doha agreement meeting highlighted that the adductor longus is the most frequent site of injury so that this syndrome can be fitted into the ARGP group.

Nevertheless, the diagnosis is difficult and it remains a complex clinical reality. The debate involves every area of pathology, including anatomy. The difficulty in approaching this pathology depends also on the etymological discrepancies between the Italian (28,29) and Anglo-Saxon languages (65) therefore it is necessary a more universally shared nomenclature.

Literature is not clear also on its correct treatment in relation with RTP time.

Comparing the results of intervention of the proposed meta-analysis, it seems that surgery allows shorter time to return to sport activity than conservative treatment in athletes with ARGP syndrome. However, the strong heterogeneity of the available studies and the lack of dedicated RCTs make it impossible to draw definitive conclusions. This data must therefore be considered as suggestive of a potential superiority, which would deserve to be studied directly through quality RCTs.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Šebečić B, Japjec M, Janković S, Čuljak V, Dojčinović B. Is chronic groin pain a Bermuda triangle of sports medicine? Acta Clin Croat. 2014;53(4):471–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pogliacomi F, Costantino C, Pedrini MF, Pourjafar S, De Filippo M, Ceccarelli F. Anterior groin pain in athlete as consequence of bone diseases: aetiopathogenensis, diagnosis and principles of treatment. Medicina dello Sport. 2014;66(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pogliacomi F, Costantino C, Pedrini MF, Pourjafar S, De Filippo M, Ceccarelli F. Anterior groin pain in athletes as a consequence of intra-articular diseases: aetiopathogenensis, diagnosis and principles of treatment. Medicina dello Sport. 2014;66(3):341–68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pogliacomi F, Pedrini MF, Pourjafar S, Pellegrini A, Paraskevopoulos A, Costantino C, Ceccarelli F. Pubalgia and soccer: real problem or overestimated. Medicina dello Sport. 2015;68(4):641–62. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Benedetto P, Niccoli G, Beltrame A, Gisonni R, Cainero V, Causero A. Histopathological aspects and staging systems in non-traumatic femoral head osteonecrosis: an overview of the literature. Acta Biomed. 2016 Apr 15;87(Suppl 1):15–24. Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weir A, Brukner P, Delahunt E, Ekstrand J, Griffin D, Khan K, et al. Doha agreement meeting on terminology and definitions in groin pain in athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(12):768–74. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morelli V, Weaver V. Groin injuries and groin pain in athletes: Part 1 Prim. Care Clin. Off. Pract. 2005;32(1):137–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bisciotti GN, Eirale C, Vuckovic Z, Le Picard P, D’Hooghe P, Chalabi H. La pubalgia dell’atleta: Una revisione della letteratura. Medicina dello Sport. 2013;65(1):119–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunt LM. Hernia Management in the Athlete. Adv Surg. 2016;50(1):187–202. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trofa DP, Mayeux SE, Parisien RL, Ahmad CS, Lynch TS. Mastering the Physical Examination of the Athlete’s Hip. Am. J. Orthop. (Belle Mead. NJ) 2017;46(1):10–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Sa D, Hölmich P, Phillips M, Heaven S1, Simunovic N, Philippon MJ. Athletic groin pain: a systematic review of surgical diagnoses, investigations and treatment. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Oct;50(19):1181–6. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson K, Strickland SM, Warren R. Hip and Groin Injuries in Athletes. Am. J Sports Med. 2001;29(4):521–33. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290042501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orso CA, Calabrese BF, D’Onofrio S, Passerini A. The rectus-adductor syndrome. The nosographic picture and treatment criteria. Ann. Ital. Chir. 1990;1(6):647–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estwanik JJ, Sloane B, Rosenberg MA. Groin Strain and Other Possible Causes of Groin Pain. Phys Sportsmed. 1990 Feb;18(2):54–64. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1990.11709972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rennie W, Lloyd D. Sportsmans Groin: The Inguinal Ligament and the Lloyd Technique. J Belgian Soc Radiol. 2018;101(S2):1–4. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Omar IM, Zoga AC, Kavanagh EC, Koulouris G, Bergin D, Gopez AG, et al. Athletic Pubalgia and ‘Sports Hernia’:Optimal MR ImagingTechnique and Findings. RadioGraphics. 2008;28:1415–38. doi: 10.1148/rg.285075217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riley G. The pathogenesis of tendinopathy. A molecular perspective. Rheumatology. 2004;43(2):131–42. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valent A, Frizziero A, Bressan S, Zanella E, Giannotti E, Masiero S. Insertional tendinopathy of the adductors and rectus abdominis in athletes: a review. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012;2(2):142–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santilli OL, Nardelli N, Santilli HA, Tripoloni DE. Sports hernias: experience in a sports medicine center. Hernia. 2016;20(1):77–84. doi: 10.1007/s10029-015-1367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmich P, Renstrom PA. Long-standing groin pain in sports people falls into three primary patterns, a ‘clinical entity’ approach: a prospective study of 207 patients * COMMENTARY. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(4):247–52. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.033373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serner A, Tol JL, Jomaah N, Weir A, Whiteley R, Thorborg K, et al. Diagnosis of Acute Groin Injuries: A Prospective Study of 110 Athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2015 Aug;43(8):1857–63. doi: 10.1177/0363546515585123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Järvinen TA, Järvinen TL, Kääriäinen M, Kalimo H, Järvinen M. Muscle injuries: biology and treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2005 May;33(5):745–63. doi: 10.1177/0363546505274714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serner AB, Mosler JL, Tol R, Bahr R, Weir A. Mechanisms of acute adductor longus injuries in male football players: A systematic visual video analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(3):158–63. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schilders E, Bharam S, Golan E, Dimitrakopoulou A, Mitchell A, Spaepen M. The pyramidalis-anterior pubic ligament-adductor longus complex (PLAC) and its role with adductor injuries: a new anatomical concept. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017 Dec;25(12):3969–77. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4688-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers WC, McKechnie A, Philippon MJ, Horner MA, Zoga AC, Devon ON. Experience with “sports hernia” spanning two decades. Ann Surg. 2008 Oct;248(4):646–64. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318187a770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellsworth M, Zoland P, Tyler MF. Invited Clinical Commentary Athletic Pubalgia and Associated. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9(8):774–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dimitrakopoulou A, Schilders E. Sportsman’s hernia? An ambiguous term. J Hip Preserv Surg. 2016 Feb 24;3(1):16–22. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hnv083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bisciotti GN, Volpi P, Zini R, Auci A, Aprato A, Belli A, Bellistri G, Benelli P, Bona S, Bonaiuti D, Carimati G, Canata GL, Cassaghi G, Cerulli S, Delle Rose G, Di Benedetto P, Di Marzo F, Di Pietto F, Felicioni L, Ferrario L, Foglia A, Galli M, Gervasi E, Gia L, Giammattei C, Guglielmi A, Marioni A, Moretti B, Niccolai R, Orgiani N, Pantalone A, Parra F, Quaglia A, Respizzi F, Ricciotti L, Pereira Ruiz MT, Russo A, Sebastiani E, Tancredi G, Tosi F, Vuckovic Z. Groin Pain Syndrome Italian Consensus Conference on terminology, clinical evaluation and imaging assessment in groin pain in athlete. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2016 Nov 29;2(1):e000142. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2016-000142. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2016-000142. eCollection 2016. Erratum in: BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2017 Jan 3;2(1):e000142corr1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zini R, Bisciotti G, Di Marzo F, Volpi P. Groin Pain Syndrome Italian Consensus. 2016; no. Mi:1–85. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roos MM, Verleisdonk EMM, Sanders FBM, Hoes AW, Stellato RK, Frederix GWJ. Effectiveness of endoscopic totally extraperitoneal (TEP) hernia correction for clinically occult inguinal hernia (EFFECT): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018 Jun 18;19(1):322. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2711-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Branci S, Thorborg K, Bech BH, Boesen M, Magnussen E, Court-Payen M, et al. The Copenhagen Standardised MRI protocol to assess the pubic symphysis and adductor regions of athletes: outline and intratester and intertester reliability. Br J Sports Med. 2015 May;49(10):692–9. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brennan D, O’Connell MJ, Ryan M, Cunningham P, Taylor D, Cronin C, et al. Secondary cleft sign as a marker of injury in athletes with groin pain: MR image appearance and interpretation. Radiology. 2005 Apr;235(1):162–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2351040045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weir A, Jansen JA, van de Port IG, Van de Sande HB, Tol JL, Backx FJ. Manual or exercise therapy for long-standing adductor-related groin pain: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Man Ther. 2011 Apr;16(2):148–54. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schöberl M, Prantl L, Loose O, Zellner J, Angele P, Zeman F, et al. Non-surgical treatment of pubic overload and groin pain in amateur football players: a prospective double-blinded randomised controlled study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017 Jun;25(6):1958–65. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4423-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hölmich P, Uhrskou P, Ulnits L, Kanstrup I, Nielsen MB, Bjerg AM. Effectiveness of active physical training as treatment for long-standing adductor-related groin pain in athletes : randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:439–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03340-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Queiroz RD, de Carvalho RT, de Queiroz Szeles PR, Janovsky C, Cohen M. Return to sport after surgical treatment for pubalgia among professional soccer players. Rev Bras Ortop. 2014;49(3):233–39. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dojčinović B, Sebečić B, Starešinić M, Janković S, Japjec M, Čuljak V. Surgical treatment of chronic groin pain in athletes. Int Orthop. 2012 Nov;36(11):231–5. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1632-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kajetanek C, Benoît O, Granger B, Menegaux F, Chereau N, Pascal-Mousselard H, et al. Athletic pubalgia: Return to play after targeted surgery. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018 Jun;104(4):469–72. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akermark C, Johansson C. Tenotomy of the adductor longus tendon in the treatment of chronic groin pain in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1992 Nov-Dec;20(6):630–3. doi: 10.1177/036354659202000604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bharam S, Feghhi DP, Porter DA, Bhagat PV. Proximal Adductor Avulsion Injuries: Outcomes of Surgical Reattachment in Athletes. Orthop J Sport Med. 2018 Jul;6(7):1–6. doi: 10.1177/2325967118784898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyers WC, Foley DP, Garrett WE, Lohnes JH, Mandlebaum BR. Management of Severe Lower Abdominal or Inguinal Pain in High-Performance Athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(1):2–8. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280011501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muschaweck U, Berger LM. Sportsmen’s Groin—Diagnostic Approach and Treatment With the Minimal Repair Technique: A Single-Center Uncontrolled Clinical Review. Sports Health. A Multidiscip. Approach. May. 2010;2(3):216–21. doi: 10.1177/1941738110367623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheen J, Pilkington JJ, Dudai M, Conze JK. The Vienna Statement; an Update on the Surgical Treatment of Sportsman’s Groin in 2017. Front Surg. 2018;5:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2018.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brunt LM. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2014. Surgical Treatment of Sports Hernia: Open Mesh Approach in Sports Hernia and Athletic Pubalgia; pp. 133–42. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paajanen H, Brinck T, Hermunen H, Airo I. Laparoscopic surgery for chronic groin pain in athletes is more effective than nonoperative treatment: A randomized clinical trial with magnetic resonance imaging of 60 patients with sportsman’s hernia (athletic pubalgia) Surgery. 2011;150(1):99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Genitsaris M, Goulimaris I, Sikas N. Laparoscopic Repair of Groin Pain in Athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(5):1238–42. doi: 10.1177/0363546503262203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lloyd DM, Sutton CD, Altafa A, Fareed K, Bloxham L, Spencer L, et al. Laparoscopic inguinal ligament tenotomy and mesh reinforcement of the anterior abdominal wall: a new approach for the management of chronic groin pain. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008 Aug;18(4):337–8. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181761fcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pogliacomi F, Calderazzi F, Paterlini M, Pompili M, Ceccarelli F. Anterior iliac spines fractures in the adolescent athlete: surgical or conservative treatment. Medicina dello Sport. 2013;65(2):231–40. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calderazzi F, Nosenzo A, Galavotti C, Menozzi M, Pogliacomi F, Ceccarelli F. Apophyseal avulsion fractures of the pelvis. A review. Acta Biomed. 2018;89(4):470–6. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i4.7632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di Benedetto P, Niccoli G, Magnanelli S, Beltrame A, Gisonni R, Cainero V, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of iliopsoas impingement syndrome after hip arthroplasty. Acta Biomed. 2019 Jan 10;90(1-S):104–9. doi: 10.23750/abm.v90i1-S.8076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pierannunzi L, Di Benedetto P, Carulli C, Fiorentino G, Munegato D, Panascì M, et al. Mid-term outcome after arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: development of a predictive score. Hip Int. 2019 May;29(3):303–9. doi: 10.1177/1120700018786025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Di Benedetto P, Barbattini P, Povegliano L, Beltrame A, Gisonni R, Cainero V, et al. Extracapsular vs standard approach in hip arthroscopy. Acta Biomed. 2016 Apr 15;87(Suppl 1):41–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009 Jul 21;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary. Control Clin Trials. 1996 Feb;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.(NHLBI) National Heart, Lung, “Study Quality Assessment Tools.” (Online) Available: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools . (Accessed: 21-Jun-2019) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, Zhang C, Li S, Sun F, Niu Y, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015 Feb;8(1):2–10. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weir CJ, Butcher I, Assi V, Lewis SC, Murray GD, Langhorne P, et al. Dealing with missing standard deviation and mean values in meta analysis of continuous outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018 Mar 7;18(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0483-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yousefzadeh A, Shadmehr A, Olyaei GR, Naseri N, Khazaeipour Z. Effect of Holmich protocol exercise therapy on long-standing adductor related groin pain in athletes: an objective evaluation. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018 Jun 26;4(1):e000343. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yousefzadeh A, Shadmehr A, Olyaei GR, Naseri N, Khazaeipour Z. The Effect of Therapeutic Exercise on Long-Standing Adductor Related Groin Pain in Athletes: Modified Hölmich Protocol. Rehabil Res Pract. 2018 Mar;12 doi: 10.1155/2018/8146819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Der Donckt K, Steenbrugge F, Van Den Abbeele K, Verdonk R, Verhelst M. Bassini’s hernial repair and adductor longus tenotomy in the treatment of chronic groin pain in athletes. Acta Orthop Belg. 2003;69(1):35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.S. J. Gore SJ, E. King E, and K. Moran K. Is stiffness related to athletic groin pain. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018 Jun;28(6):1–10. doi: 10.1111/sms.13069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.King E, Franklyn-Miller A, Richter C, O’Reilly E, Doolan M, Moran K, et al. Clinical and biomechanical outcomes of rehabilitation targeting intersegmental control in athletic groin pain: prospective cohort of 205 patients. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Aug;52(16):1054–62. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sheen AJ, Stephenson BM, Lloyd DM, Robinson P, Fevre D, Paajanen H, et al. Treatment of the sportsman’s groin’: British Hernia Society’s 2014 position statement based on the Manchester Consensus Conference. Br J Sports Med. 2014 Jul;48(14):1079–87. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]