Abstract

Background: More than five decades ago, thalassemia major (TDT) was fatal in the first decade of life. Survival and quality of life have improved progressively thanks to the implementation of a significant advance in diagnostic and therapeutic methods, consisting mainly of a frequent transfusion program combined with intensive chelation therapy. Improvement also includes imaging methods used to measure liver and cardiac iron overload. Improved survival has led to a growing number of adults requiring specialised care and counselling for specific life events, such as sexual maturity and acquisition of a family. Aims of the study: The main aim is to present the results of a survey on the marital and paternity status in a large population of adult males with TDT and NTDT living in countries with a high prevalence of thalassemia and a review of current literature using a systematic search for published studies. Results: Ten out of 16 Thalassemia Centres (62.5%) of the ICET-A Network, treating a total of 966 male patients, aged above 18 years with β- thalassemias (738 TDT and 228 NTDT), participated in the study. Of the 966 patients, 240 (24.8%) were married or lived with partners, and 726 (75.2%) unmarried. The mean age at marriage was 29.7 ± 0.3 years. Of 240 patients, 184 (76.6%) had children within the first two years of marriage (2.1 ± 0.1 years, median 2 years, range 1.8 - 2.3 years). The average number of children was 1.32 ± 0.06 (1.27 ± 0.07 in TDT patients and 1.47 ± 0.15 in NTDT patients; p: >0.05). Whatever the modality of conception, 184 patients (76.6%) had one or two children and 1 NTDT patient had 6 children. Nine (4.8%) births were twins. Of 184 patients, 150 (81.5%) had natural conception, 23 (12.5%) required induction of spermatogenesis with gonadotropins (hCG and hMG), 8 (4.3%) needed intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and 3 adopted a child. 39 patients with TDT and NTDT asked for medical help as they were unable to father naturally: 7 TDT patients (17.9%) were azoospermic, 17 (37.7%) [13 with TDT and 4 with NTDT] had dysspermia and 15 (33.3%) [13 with TDT and 2 with NTDT] had other “general medical and non-medical conditions”. Conclusions: Our study provides detailed information in a novel area where there are few contemporary data. Understanding the aspects of male reproductive health is important for physicians involved in the care of men with thalassemias to convey the message that prospects for fatherhood are potentially good due to progressive improvements in treatment regimens and supportive care. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: thalassemia, marital status, paternity, comorbidities, endocrine complications, iron overload, chelation therapy

Introduction

Thalassemias are the most common monogenic hematologic disorders with a worldwide distribution (1). Based on clinical and haematological features and molecular characterization, β-thalassemia is classified into 3 distinct categories: thalassemia major, also known as transfusion dependent thalassemia (TDT), thalassemia intermedia [characterized usually as non-transfusion dependent thalassemia (NTDT)], and thalassemia minor (2-4). It is estimated that more than 60,000 babies are born annually with thalassemia major and more than 80 million are carriers of β-thalassemia (1). The severity of the disease depends on the degree of imbalance between a- and β-globin chain synthesis leading to ineffective erythropoiesis (IE), bone marrow expansion and a chronic hemolytic anemia (2-4). Anemia is treated with frequent packed red blood cell (PRBC) transfusions which result in the accumulation of iron, released by the breakdown products of hemoglobin (heme and iron) and increased absorption of iron from the intestine related to anemia (5-7).

Between 1949 and 1957, in Ferrara, only 9% of patients reached the age of 6 years, and by the end of the 1970s, half of Italian thalassemic patients had died before the age of 12 years. Since the 1980s, due to treatment with a combination of regular transfusions and chelation, and/or bone marrow transplantation, survival improved significantly, but still remains suboptimal at national levels (5).

Today, in developed countries, survival of patients on conventional treatment has increased to 40-50 and more years, and keeps improving (6-8). Improved patient care has now expanded to encourage patients to aspire to the vocational, social, sexual, and reproductive goals of their healthy peers (9).

Overall, hundreds of uneventful pregnancies have occurred in women with TDT and NTDT (10,11); apart from infertility(9), only a few studies have addressed the sexual and reproductive health of men with thalassemias (12-14).

The main aim of the present study was to investigate the marital and paternity status in a large population of male patients over the age of 18 years with TDT and NTDT living in countries with a high prevalence of β- thalassemia.

Survey Design and Participants

Questionnaire development

A. First step

In April 2018, the Coordinator (VDS) of the International Network of Clinicians for Endocrinopathies in Thalassemia and Adolescence Medicine (ICET-A)(15,16) designed and promoted a survey questionnaire to collect data on “Marital and paternity status in patients with TDT and NTDT, aged over 18 years”.

The criteria for patients’ inclusion in the survey were: 1) Male patients with TDT or NTDT who were over the age of 18 yrs at the time of data collection. The term TDT was based on clinical (regular transfusion with packed red cells, every 2-3 weeks, since the first years of life), haematological and biochemical findings, and the term NTDT was applied to patients with mild to moderate anemia, splenomegaly, mild degree of growth impairment, requiring red blood transfusions in certain circumstances, such as: delayed puberty, infections, surgery, pregnancy or falling Hb in adult life (1-4).

Exclusion criteria were:1) TDT and NTDT patients with incomplete records, 2) bone marrow transplanted patients, 3) eating disorders, and 4) renal insufficiency.

B. Second step

All ICET-A members were requested, by mail, to comment on the data included in the preliminary questionnaire draft. The study was planned to fulfil the following information: personal doctors’ data (place of work, specialization), patients’ demographic characteristics including age, marital status and paternity, patients’ transfusion and iron chelation regime, serum ferritin level and associated complications.

Patients were classified as ‘married’ or ‘lived with partners’. For these individuals, the duration of marriage, the spouse’s health status (healthy, β-thalassemia carrier, TDT or NTDT), number of children born after natural conception, induction with gonadotrophins or artificial insemination with a sperm donor, intra-cytoplasmic spermatozoan injection (ICSI), or adoption were requested.

C. Third step

After final approval, the questionnaire was sent to the 16 Thalassemia Centers of the ICET-A Network with an official invitation to participate in the survey. The deadline to return the completed questionnaire in an Excel format was fixed for 4 months.

For uniform collection of data, the diagnosis of organ dysfunction was based on the following definitions supported by laboratory results, as well as confirmatory clinical evidence: a) cardiac complications were defined as the presence of any of the following: history of heart failure, left and/or right mild or overt ventricular dysfunction, arrhythmia with or without myocardial magnetic resonance imaging siderosis (MRI T2* <20 msec) (17-19); b) liver dysfunction was defined by the presence of organ enlargement associated with significant and persistent increase of alanine aminotransferases (ALT > 41 IU/L), with or without positive blood tests for hepatitis C virus antibodies (HCV ab) and HCV-RNA; c) presence of gallstones in the gallbladder assessed by ultrasonography (USG); d) extramedullary hematopoiesis (EMH) diagnosed by USG, computed tomography scan (CT scan) or MRI for detection of extramedullary hematopoietic foci, with or without symptoms; e) renal complications were based on the presence of functional abnormalities, such as: abnormal creatinine clearance, hypercalciuria, proteinuria or in presence of USG renal cyst or renal lithiasis; f) bone abnormalities were defined as presence of facial bone deformities; g) others: any additional significant patient pathology.

Assessment of iron overload was mainly based on the serum ferritin levels. A value of < 1,000 ng/ml indicated mild grade of iron load, of 1,000-2,500 ng/ml moderate and of > 2,500 ng/mL severe grade of iron load (20,21).

The associated endocrine complications were classified as follows: a) primary hypothyroidism (subclinical and overt) were defined by normal or low free thyroxine and abnormally high levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone: >10 μIU/mL); b) secondary or central hypothyroidism was defined by low free thyroxine and normal or decreased TSH(22); c) the diagnosis of thyroid cancer was based on histopathology/cytopathology; d) hypogonadism was based on the criteria reported in our previous publication(9); e) diabetes, both insulin and non-insulin dependent, were defined according to the standards of American Diabetes Association(23); f) latent hypocortisolism was diagnosed in the presence of basal cortisol < 4.2 μg/dl (98 nmol/l)(24), and g) for the diagnosis of growth hormone deficiency (GHD) in adults the recommendations of American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists were used (25).

The diagnosis of osteopenia or osteoporosis was based on the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, assessed by Dual Energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (26).

Infertility was defined as failure to achieve pregnancy after ≥ 12 months of regular unprotected sexual intercourse (27).

The term dysspermia was used to encompass different conditions related to sperm quality and function (low sperm concentration, oligospermia, poor sperm motility, asthenospermia and abnormal sperm morphology, teratospermia). Semen analysis was performed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines (28). Patients were considered to be normozoospermic when sperm concentration exceeded 20 x 106/mL, oligozoospermic between 5 and 20 x 106/mL, severely oligozoospermic below 5 x 106/mL, and cryptozoospermic when spermatozoa were detected only after careful analysis of the concentrated sample (29). When no spermatozoa were detected in any field, both before and after centrifugation, patients were considered to be azoospermic.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for our study was obtained in accordance with local institutional requirements and with the Declaration of Helsinki (http://www.wma.net).

Statistical analysis

Data entry and analysis were done using SPSS software package for windows version 13. Descriptive statistics included frequency and percentage for qualitative variables; mean, median, standard deviation (SD), standard error (SE), lower bound and upper bound, and interquartile range for quantitative variables. Statistical significance of the differences between variables was assessed using the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Chi square and Fisher’s Exact tests were used to calculate the probability value for the relationship between two dichotomous variables. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

a. Participating Centres and Patients’ marital status

Ten of 16 (62.5%) ICET-A Network Thalassemia centres participated in the study: Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, India, Iran, Italy (2 centres), Oman, Qatar and Turkey. A total of 966 patients with β-thalassemia (738 TDT and 228 NTDT) with a minimum age of 18 years by the end of April 2018 were included in the study. The countries’ distribution of patients is illustrated in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of male patients over age 18yrs with TDT and NTDT

| Country | Number of patients with TDT | Number of patients with NTDT | Total number of patients | Married or living with partners N. (%) | Unmarried patients N. (%) |

| Bulgaria | 14 | 0 | 14 | 1 (7.1) | 13 (92.8%) |

| Cyprus | 106 | 16 | 122 | 70 (57.3) | 52 (42.6%) |

| Greece | 156 | 41 | 197 | 60 (30.4) | 137 (69.5%) |

| India | 32 | 3 | 35 | 6 (17.1) | 29 (82.8%) |

| Iran | 272 | 87 | 359 | 45 (12.5) | 314 (87.4%) |

| Italy (1) | 19 | 15 | 34 | 8 (23.5) | 26 (76.4%) |

| Italy (2) | 30 | 17 | 47 | 16 (34) | 31 (65.9%) |

| Oman | 38 | 15 | 53 | 20 (37.7) | 33 (62.3%) |

| Qatar | 38 | 8 | 46 | 8 (17.3) | 38 (82.6%) |

| Turkey | 33 | 26 | 59 | 6 (10.1) | 53 (89.8%) |

| Total | 738 | 228 | 966 | 240 (24.8%) | 726 (75.2%) |

The total patients’ median age at last observation was 42 years; 95% confidence interval for mean: lower bound 40.3 and upper bound 42.6; age range 18- 66 years. The age (mean ± SE) in 185 TDT patients was 40.0 ± 0.59 and in 55 NTDT patients was 46.4 ± 1.42 years, respectively (P <0.001).

b. Age at marriage or at starting a live-in relationship

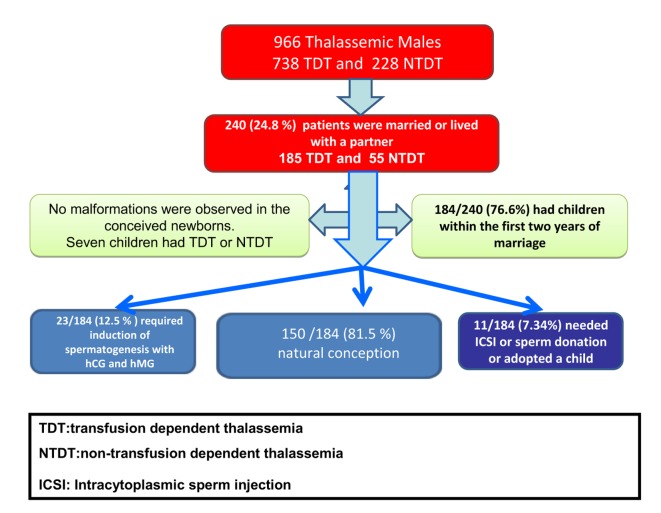

Of 966 patients with TDT or NTDT, 240 (24.8%) were married or lived with a partner. Of the 240 patients, 185 (77.1%) had TDT and 55 (22.9%) NTDT (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Marital status, fertility rate and assisted reproduction in thalassemia patients enrolled in our study

19 patients (7.9%; 18 TDT and 1 NTDT) were married to a woman with TDT or NTDT, and 10 patients (4.1%; 5 TDT and 5 NTDT) married a woman with β-thalassemia trait (Table 2). All patients received genetic counselling before marriage or taking a partner. The minimum and maximum age at marriage or living with a partner, in both group of patients, was 29 and 30.4 years. The mean age (± SE) was not different in the two groups of patients (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Mean age at marriage or at starting a relationship with a woman with TDT, NTDT or carrier for β-thalassemia

| Age at marriage or at starting a live-in relationship | TDT and NTDT (240) | TDT (185) | NTDT (55) |

| Mean (SE) | 29.73 ± 0.37 | 29.72 ± 0.42 | 29.76 ± 0.79 |

| Lower Bound | 29.00 | 28.90 | 28.18 |

| Upper Bound | 30.46 | 30.55 | 31.35 |

| Median | 30.00 | 30.00 | 30.00 |

| Std. Deviation | 5.73 | 5.70 | 5.86 |

| Wife with TDT (N) | 19 | 18 | 1 |

| Wife with NTDT (N) | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Wife with P-thalassemia minor (N) | 10 | 5 | 5 |

c. Fertility rate and assisted reproduction

184 out of 240 patients with TDT and NTDT (76.6%) had children. The mean age at birth of the first child was 31.84 years. The interval between the age at marriage (or at start of a live-in relationship) and the birth of the first and last child, expressed in interval years (mean ± SE) were: total group 2.1 ± 0.12 years, TDT: 2.1± 0.15 years, NTDT: 2.1 ± 0.22 years (P:NS); last child interval: total group 4.5 ± 0.26 years, TDT: 4.3 ± 0.30 years, NTDT: 5.1 ± 0.53 years (P > 0.05).

The average number of children was 1.32 ± 0.06 (1.27 ± 0.07 in TDT patients and 1.47 ± 0.15 in NTDT patients). Whatever the modality of conception, 184 patients (76.6%) had one or more than one child and 1 NTDT patient had 6 children, at the age of 21, 24, 25, 40, 41 and 42 years (Table 3). 4.8% of births (n =9) were twins.

Table 3.

Number of TDT and NTDT registered as having children whatever the modality of procreation

| TDT and NTDT (240) | TDT (185) | NTDT (55) | P value | |

| Number of patients with children | 184 (76.6%) | 139 (75.1%) | 45 (81.8%) | 0.3 |

| Number of children: | ||||

| Mean (SE) | 1.32 ± 0.06 | 1.27 ± 0.07 | 1.47 ± 0.15 | > 0.05 |

| Lower Bound | 1.19 | 1.13 | 1.17 | |

| Upper Bound | 1.45 | 1.41 | 1.78 | |

| Median | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Std. Deviation | 1.014 | 0.979 | 1.120 | |

| Number of children | TDT and NTDT | TDT | NTDT | |

| 1 | 82 | 63 | 19 | > 0.05 |

| 2 | 80 | 60 | 20 | |

| 3 | 16 | 12 | 4 | |

| 4 | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total number of children | 184 | 139 | 45 | |

Thirty patients divorced and one patient married 3 times (at the age of 22, 41 and 42 years). No malformations were observed in the newborns. Seven children had TDT or NTDT.

150 out of 184 patients (81.5%) reported a natural conception, 23 (12.5%) with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism requiring induction of spermatogenesis with gonadotropins (hCG and hMG), and 2 (1.4%) needed intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and 3 (1.6%) adopted a child (Figure 1 and Table 4).

Table 4.

Clinical description of modality of procreation in TDT and NTDT patients and reported causes of infertility

| Total number of patients: TDT and NTDT N. (%) | TDT patients with children N. (%) | NTDT patients with children N. (%) | P value: TDT vs. NTDT | |

| Modalities of conception or paternity in patients requiring to be father | ||||

| Natural conception (NC) | 150 (81.5%) | 109 (78.5%) | 41 (91.1%) | 0.16 |

| Induced by gonadotrophins | 23 (12.5%) | 21 (15.1%) | 2 (4.5%) | |

| Sperm donation (AID) | 6 (3.3%) | 6 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| ICSI conception | 2 (1.1%) | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (2.2%) | |

| Adoption (AD) | 3 (1.6%) | 2 (1.4%) | 1 (2.2%) | |

| Total | 184 | 139 | 45 | |

| Causes of infertility in patients asking for fathering a child | ||||

| Azoospermia | 7 (15.6%) | 7 (17.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0.31 |

| Dysspermia | 17 (37.8%) | 13 (33.3%) | 4 (66.7%) | |

| Medical conditions | 6 (13.3%) | 6 (15.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Others | 15 (33.3%) | 13 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | |

| Total | 45 | 39 | 6 | |

Legend: ICSI: Intracytoplasmic sperm injection

Of 45 patients with TDT and NTDT who were unable or unwilling to father a child naturally, 7 patients with TDT (17.9%) had azoospermia; 17 (37.7%; 13 with TDT and 4 with NTDT) dysspermia, and 15 (33.3%; 13 with TDT and 2 with NTDT) had “medical and non-medical conditions” (e.g. associated comorbidities, no response to gonadotrophins after 2 years of treatment, presence of hemoglobinopathy in their wives) (Table 4).

d. Comorbidities and Endocrine complications

128 (53.3%) out of 240 patients had been splenectomised. HCV antibodies were present in 56 out of 231 patients (23.3%; missing data in 9) and HCV-RNA positivity in 17 out of 223 patients (7.1%, missing data in 17).

There was no statistical difference in HCV antibodies and HCV-RNA positivity in TDT vs NTDT= p:0.08 and 0.6, respectively.

The most common reported comorbidities were: osteopenia/osteoporosis (50%) and cholelithiasis (45.0%), followed by cardiac complications (17.5%). No cases of heart and liver failure or malignancies were reported.

A detailed presentation of both groups of patients is given in table 5.

Table 5.

Reported comorbidities in 240 TDT and NTDT married male patients or living-in relationship with a woman

| Comorbidities | Total (240 patients) | TDT (185 patients) | NTDT (55 patients) | P value: TDT vs. NTDT |

| Splenectomy | 128 (53.3%) | 91 (49.1%) | 37 (67.2%) | 0.02 |

| Osteopenia/Osteoporosis | 120 (50%) | 95 (51.3%) | 25 (45.4%) | 0.44 |

| Cholelithiasis | 108 (45.0%) | 76 (41.0%) | 32 (58.1%) | 0.025 |

| Cardiac complications | 42 (17.5%) | 33 (17.8%) | 9 (16.3%) | 0.8 |

| Liver dysfunction | 24 (10%) | 21 (11.3%) | 3 (5.4%) | 0.2 |

| Extramedullary hematopoiesis | 20 (8.3%) | 10 (5.4%) | 10 (18.1%) | 0.002 |

| Kidney stones | 12 (5%) | 11 (5.9%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0.22 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 11 (4.6%) | 7 (3.7%) | 4 (7.2%) | 0.28 |

| Renal complications | 10 (4.2%) | 10 (5.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.08 |

| Adrenal mass | 3 (1.3%) | 3 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.34 |

Comparison between those with and without children was not statistically significant for all reported comorbidities (P > 0.05).

The commonest endocrine complication was hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (51/240 patients; 21.3%). In the whole group of patients, non-insulin dependent diabetes, primary hypothyroidism, central hypothyroidism and hypoparathroidism were reported in 11.7%, 10.0%, 8.3% and 7.5%, respectively. The less commonly reported endocrine complications were GHD, latent hypocortisolism and thyroid cancer (3.3%, 1.7% and 1.3%, respectively).

The percentages in TDT and NTDT are reported in table 6.

Table 6.

Endocrine complications in 240 TDT and NTDT married male patients or living-in relationship with a woman

| Endocrine complications | Total TDT and NTDT (240 patients) | TDT (185 patients) | NTDT (55 patients) | P value: TDT vs. NTDT |

| HH | 51 (21.3%) | 47 (25.4%) | 4 (7.2%) | 0.004 |

| With children / Without children | 31/20 | |||

| Non- insulin dependent diabetes | 28 (11.7%) | 26 (14.0%) | 2 (3,6%) | 0.03 |

| With children/Without children | 24/4 | |||

| Primary hypothyroidism | 24 (10.0%) | 22 (11.8%) | 2 (3.6%) | 0.07 |

| With children/Without children | 18/6 | |||

| Central hypothyroidism | 20 (8.3%) | 19 (10.2%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0.04 |

| With children/Without children | 13/7 | |||

| Hypoparathyroidism | 18 (7.5%) | 15 (8.1%) | 3 (5.4%) | 0.51 |

| With children/Without children | 14/4 | |||

| Insulin dependent diabetes | 14 (5.8%) | 13 (7.0%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0.15 |

| With children/Without children | 8/6 | |||

| Growth hormone deficiency | 8 (3.3%) | 6 (3.2%) | 2 (3.6%) | 0.88 |

| With children/Without children | 4/4 | |||

| Latent hypocortisolism | 4 (1.7%) | 3 (1.6%) | 1 (1.8%) | 0.92 |

| With children/Without children | 4/0 | |||

| Thyroid cancer | 3 (1.3%) | 3 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.34 |

| With children/Without children | 2/1 |

Legend: HH = Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism

Almost all endocrine complications were more prevalent in TDT patients compared to NTDT patients.

Comparison between those with and without children was not statistically significant for all reported variables (P > 0.05) except for hypogonadism(P < 0.05).

e. Chelation therapy and serum ferritin

The majority of TDT and NTDT patients received iron chelation therapy for at least 2 years before paternity: with desferioxamine (DFO) 91 (37.9%), deferiprone (DFP): 33 (13.8%) and a combined therapy with both chelating agents 54 (22.5%) patients.

Substantially, in the year of paternity there were no significant changes in the regime of drugs of chelation treatment, although this information was missing in 62 patients (25.8%).

At the last observation, the most common chelating regime was the combination of DFO plus DFP (75 patients; 31.2%), followed by deferasirox (DFX: 53 patients, 22.0%). DFO or DFP monotherapy was given to 76 patients (31.6%). In 36 patients, this information was missing (15%).

The total average serum ferritin (SF) level in both groups of patients before paternity was 2,281 ± 162 ng/ml, with a range of 100 -13,085 ng/ml. No substantial changes of SF levels were observed in the year of paternity (2,042 ± 161 ng/ml; P > 0.05). The highest registered level was 9,500 ng/ml. A detailed description of SF levels in TDT and NTDT is reported in table 7.

Table 7.

Iron chelation therapy and serum ferritin levels before, during and after paternity

| TDT patients | Serum ferritin at least 2 years before paternity (A) | Serum ferritin in the year of the first paternity (B) | Last serum ferritin level (C) | P value: A vs B | P value: B vs C |

| Mean | 2581.0 ± 191.5 | 2211.8 ± 181.8 | 1825.7 ± 179.9 | 0.115 | <0.001 |

| Lower Bound | 2202.7 | 1852.0 | 1470.7 | ||

| Upper Bound | 2959.2 | 2571.6 | 2180.7 | ||

| Median | 2000.0 | 1500.0 | 949.5 | ||

| Standard Deviation (SD) | 2475.6 | 2089.5 | 2413.7 | ||

| Minimum | 105 | 105 | 91 | ||

| Maximum | 13085 | 9495 | 15484 | ||

| Interquartile Range | 2700 | 2508 | 1626 | ||

| NTDT patients | (A) | (B) | (C) | ||

| Mean | 1059.9 ± 162.73 | 1387.1 ± 328.31 | 1165.5 ± 222.9 | 0.48 | 0.083 |

| Lower Bound | 731.0 | 719.1 | 717.7 | ||

| Upper Bound | 1388.8 | 2055.0 | 1613.4 | ||

| Median | 620.0 | 600.0 | 559.0 | ||

| Standard Deviation (SD) | 1041.9 | 1914.3 | 1592.3 | ||

| Minimum | 100 | 100 | 105 | ||

| Maximum | 5000 | 9500 | 9500 | ||

| Interquartile Range | 1210 | 1430 | 943 |

At the last observation, the SF level was on average 1,680 ± 149 ng/ml (1,825 ± 179.9 ng/ml in TDT patients and 1,165 ± 222.9 ng/ml in NTDT). In both groups the highest registered level was 15,484 ng/ml and 9,500 ng/ml, respectively (Table 7).

f. Relationship between serum ferritin level and some comorbidities

The relationship between serum ferritin levels, ALT, and the most common registered comorbidities and endocrine complications, assessed with Pearson Chi-Square, at first paternity, was statistically significant only for ferritin versus cholelithiasis (chi square = 6.2; p: 0.04) and for serum ferritin. At last observation, a statistically significant relationship was found both for cholelithiasis (chi square = 16.2; P <0.001) and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (chi square: 7.7; P: 0.02).

Discussion

More than five decades ago, TDT was a fatal disease in the first decade of life. This poor prognosis has progressively improved and survival increased considerably, due to the implementation of significantly advanced diagnostic and therapeutic methods, consisting mainly of a frequent transfusion program combined with intensive chelation therapy, and improved hematological, biochemical, molecular and imaging methods (1-3). Today, the expectation for having a family is a key component of quality of life and an important aspiration for many patients with thalassemias (7-10).

Therefore, fertility-related issues are important in the management of patients with thalassemias.

Up to now, attention has been mainly focused on issues of fertility in women with thalassemias, with relatively low interest in the reproductive issues faced by male TDT and NTDT patients (11-14). To investigate the effects of thalassemias, its treatment and complications on male fertility, we reviewed the current literature using a systematic search for published studies and promoted a multicentre survey through the ICET-A network in different countries with high prevalence of β-thalassemia.

Reviewing the literature, we found only two studies, both from Iran, reporting data on the marital status, with very limited data on paternity of patients with TDT and NTDT (12,13).

The first study on the marital status of 228 TDT patients over 15 years of age, was done at the Department of Pediatrics, Children and Adolescent Health Research Centre of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (Iran). Of the whole group of 228 patients only 32 (14%) were married, 24 (75%) of whom were males. Of the married male patients, only 7 had children. The mean ferritin levels for married patients (both males and females) was 4,419 ± 2,727 ng/ml (13).

The second paper reviewed 74 patients with NTDT. Among them, 50 (67.7%) were female (mean age: 29.6±8.1 years), 21 of whom (42%) were married. Out of 24 male patients, 14 (56.0%) were married. Their age at marriage was 25.3± 4.2 years. Among the married male patients, 11 (78.5%) had children within the first two years of marriage (12). Common reported complications were facial disfigurements, HCV related hepatitis, mellitus and cardiac diseases (12).

In our survey, 240 (24.8%) out of 966 male TDT and NTDT were married or lived with partners, and 726 (75.2%) unmarried. The mean age at marriage or living with partner was 29.7 ± 0.3 years. Out of 240 patients 184 (76.6%) had children within the first two years of marriage (2.1± 0.1 years, median 2 years, range 1.8 - 2.3 years). The total average number of children per family was 1.32 ± 0.065 (1.27 ± 0.072 in TDT patients and 1.47 ± 0.151 in NTDT patients; p >0.05). Whatever the modality of conception, 184 patients had one or two children and 1 NTDT patient had 6 children. Nine births (4.8%) were twins.

In the general population, infertility is a common clinical problem affecting 13 to 15% of couples worldwide. Male infertility is the singular cause of infertility in nearly 20% of infertile couples (30,31).

Extreme transfusional iron input in thalassemia patients due to regular blood transfusions and hemolysis as well as increased intestinal iron absorption, lead to iron overload, facilitating the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (32). ROS can negatively affect fertility via a number of pathways, including interference with capacitation and possible damage to sperm membrane and DNA, which may impair the sperm’s potential to fertilize an egg and develop into a healthy embryo (33-35).

A higher degree of DNA damage in spermatozoa of β-thalassaemia patients was found in one of our studies (36). In addition, patients with low sperm concentrations were more likely to have a higher degree of defective chromatin packaging. The positive association between low serum ferritin levels and abnormal sperm morphology suggested a potential detrimental effect on spermatogenesis by the iron chelator desferrioxamine, which is used to reduce iron overload (37). Furthermore, the increase in sperm DNA damage and the negative correlation between sperm motility and DNA damage, found by other researchers, suggest that iron overload in β-thalassaemia patients predisposes sperm to oxidative injury (38,39).

Other potential negative prognostic factors that should be considered in thalassemias are the chronic hypoxia due to anemia (40), the alteration of trace elements and antioxidant enzymes(35), the folate deficiency (41) and the concomitant presence of other comorbidities (42).

At least 2 years before paternity, the majority of our TDT and NTDT patients received iron chelation therapy with desferioxamine (DFO) 91 (37.9%), deferiprone (DFP) 33 (13.8%) or combined therapy with both chelating agents 54 (22.5%) patients.

It is interesting to note that our married patients maintained an efficient chelation regime therapy around the time of paternity, mainly consisting of DFO in 75.5% of cases and of DFO or DFP either as monotherapy or in combination with DFO. At the last observation, the commonest iron chelation regimes were the combination of DFO and DFP in 75 (33.3%) patients, followed by DFX (53 patients; 23,5%) and DFO (41 patients; 18,2%) patients. The mean ferritin levels at last observation indicates that patients were on a more efficient chelation regime probably because they became more compliant to treatment after paternity.

Overall, comorbidities and endocrine complications were observed in both TDT and NTDT groups of patients. Osteopenia/osteoporosis represents a common cause of morbidity (51.3% of TDT and 45.4% of NTDT patients). The mechanism of pathogenesis of reduced bone mass is multifactorial and complex. Progressive bone marrow expansion, hypogonadism, a defective GH-IGF-1 axis, and imbalanced cytokine profiles play major roles in the development of osteopenia/osteoporosis. Iron overload, iron chelation therapy, liver disease and other endocrine dysfunctions could be additional factors (43-45). Some studies suggest that there is a gender difference not only in the prevalence but also in the severity of osteoporosis syndrome in thalassemias (male patients are more frequently and more severely osteopenic/osteoporotic than females), although some other studies reported no gender variation (46).

Our large multicentre study confirms the high prevalence of cholelithiasis in patients with thalassemias, with significantly higher prevalence of 58.1% in NTDT versus 41.0% in TDT in male patients over the age of 18 years. Given the usual benign course of asymptomatic patients, preventive cholecystectomy usually is not considered mandatory, but careful follow-up is suggested because cholelithiasis predisposes patients to complications such as pancreatitis, cholangitis, and acute bile tract obstruction (47,48).

Overall, disease-related endocrine complications were more prevalent among patients with TDT than in patients with NTDT, although in the latter group the prevalence of some endocrine complications (e.g. central hypothyroidism, latent hypocortisolism, GHD) was higher compared to other reports (49-51).

The originality of our study is that it provides detailed information in an area where the contemporary data are few. Understanding the aspects of male reproductive health is important for physicians involved in the care of men with thalassemias to convey the message that prospects for fatherhood are potentially promising due to improvements in treatment regimens and supportive care.

However, some limitations should be considered. In spite of good knowledge about the genetic transmission of the disease, 19 patients (7.9%; 18 TDT and 1 NTDT) married a woman with TDT or NTDT, and 10 patients (4.1%; 5 TDT and 5 NTDT) married a woman with β-thalassemia minor. Due to the paucity of information stated in the medical records this aspect was not fully explored. Their decision may have been related to the high quality of care received in their place of residency and the hope that gene therapy could soon be available to cure the genetic disease.

Although our study provides some insights into the reproductive health experience of persons with TDT and NTDT, further work is required. Areas of concern include patients’ quality of life in married and unmarried patients.

In conclusion

More than five decades ago, thalassemia major was fatal in the first decade of life. This poor prognosis has changed since survival started to improve progressively due to the implementation of significantly improved diagnostic and therapeutic methods. One of the main objectives of medical teams caring for patients with thalassemias is to offer the best achievable quality of life. In the current social frame, marriage and reproduction are considered to be important among the standards of normal social behavior. This leads to a growing number of adults in need of specialised care and counselling during specific life events such as reproductive health issues and the establishment of a family. The comprehensive data presented in this article could serve as a reliable reference for physicians counselling thalassemia patients for whom fertility is a major concern. With recent advances in assisted fertility techniques, more male thalassemic patients may be helped to father children. However, because infertility cannot be predicted on an individual basis, it is important to continue the policy of offering sperm preservation in patients with spontaneous puberty and in those treated with gonadotropins. Since fertility preservation is becoming more and more important, practical materials and development of professional practice guidelines should be a high priority aspect for thalassemia associations and medical societies.

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Williams TN, Weatherall DJ. World distribution, population genetics and health burden of the hemoglobinopathies. Cold Spring Harb Prospects Med. 2012;2:a011692. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao A, Kan YW. The prevention of thalassemia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3:a011775. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weatherall DJ. Phenotype-genotype relationships in monogenic disease: lessons from the thalassaemias. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:245–55. doi: 10.1038/35066048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thein SL. The emerging role of fetal hemoglobin induction in non-transfusion-dependent thalassemia. Blood Rev. 2012;26(Suppl 1):S35–39. doi: 10.1016/S0268-960X(12)70011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borgna-Pignatti C. The life of patients with thalassemia major. Haematologica. 2010;95:345–348. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.017228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berdoukas V, Modell B. Transfusion-dependent thalassaemia: a new era. Med J Aust. 2008 Jan 21;188:68–69. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saliba AN, Harb AR, Taher AT. Iron chelation therapy in transfusion-dependent thalassemia patients: current strategies and future directions. J Blood Med. 2015;6:197–209. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S72463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parakh N, Chandra J, Sharma S, Dhingra B, Jain R, Mahto D. Efficacy and Safety of Combined Oral Chelation With Deferiprone and Deferasirox in Children With β-Thalassemia Major: An Experience From North India. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39:209–213. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Sanctis V, Soliman AT, Yassin MA, Di Maio S, Daar S, Elsedfy H, Soliman N, Kattamis C. Hypogonadism in male thalassemia major patients: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Acta Biomed. 2018;89:6–15. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i2-S.7082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rjaeefard A, Hajipour M, Tabatabaee HR, Hassanzadeh J, Rezaeian S, Moradi Z, Sharafi M, Shafiee M, Semati A, Safaei S, Soltani M. Analysis of survival data in thalassemia patients in Shiraz, Iran. Epidemiol Health. 2015:36. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2015031. doi.org/10.4178/epih/e 2015031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlberg KT, Singer ST, Vichinsky EP. Fertility and Pregnancy in Women with Transfusion-Dependent Thalassemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2018;32:297–315. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zafari M, Kosaryan M. Evaluation of marriage and childbirth in patients with non-transfusion dependent beta thalassemia major at Thalassemia Research Center of Sari, Iran. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. 2015;2:36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miri-Aliabad G, Fadaee M, Khajeh A, Naderi M. Marital Status and Fertility in Adult Iranian Patients with β-Thalassemia Major. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2016;32:110–113. doi: 10.1007/s12288-015-0510-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carbone S. Thalassemia in Messina: a sociological approach to chronic disease. Thalassemia Reports. 2014;4:2207. doi: 10.4081/thal.2014.2207. [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Sanctis V, Soliman AT. ICET- A an opportunity for improving thalassemia management. J Blood Disord. 2014;1:2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Sanctis V, Soliman AT, Canatan D, Tzoulis P, Daar S, Di Maio S, Elsedfy H, Yassin MA, Filosa A, Soliman N, Mehran K, Saki F, Sobti P, Kakkar S, Christou S, Albu A, Christodoulides C, Kilinc Y, Al Jaouni S, Khater D, Alyaarubi SA, Lum SH, Campisi S, Anastasi S, Galati MC, Raiola G, Wali Y, Elhakim IZ, Mariannis D, Ladis V, Kattamis C. An ICET-A survey on occult and emerging endocrine complications in patients with β-thalassemia major: Conclusions and recommendations. Acta Biomed. 2019;89:481–489. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i4.7774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cogliandro T, Derchi G, Mancuso L, Mayer MC, Pannone B, Pepe A, Pili M, Bina P, Cianciulli P, De Sanctis V, Maggio A. Society for the Study of Thalassemia and Hemoglobinopathies (SoSTE). Guideline recommendations for heart complications in thalassemia major. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2008;9:515–525. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3282f20847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buxton AE, Calkins H, Callans DJ, DiMarco JP, Fisher JD, Greene HL, Haines DE, Hayes DL, Heidenreich PA, Miller JM, Poppas A, Prystowsky EN, Schoenfeld MH, Zimetbaum PJ, Heidenreich PA, Goff DC, Grover FL, Malenka DJ, Peterson ED, Radford MJ, Redberg RF. American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards; (ACC/AHA/HRS Writing Committee to Develop Data Standards on Electrophysiology). ACC/ AHA/HRS 2006 key data elements and definitions for electrophysiological studies and procedures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards. Circulation. 2006;114:2534–2570. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.180199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meloni A, Dell’Amico M, Favilli B, Aquaro G, Festa P, Chiodi E, Renne S, Galati MC, Sardella L, Keilberg P, Positano V, Lombardi M, Pepe A. Left Ventricular Volumes, Mass and Function normalized to the body surface area, age and gender from CMR in a large cohort of well-treated thalassemia major patients without myocardial iron overload. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13(Suppl 1):P305. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson LJ, Holden S, Davis B, Prescott E, Charrier CC, Bunce NH, Firmin DN, Wonke B, Porter J, Walker JM, Pennell DJ. Cardiovascular T2-star (T2*) magnetic resonance for the early diagnosis of myocardial iron overload. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:2171–2179. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olivieri NF, Nathan DG, MacMillan JH, Wayne AS, Liu PP, McGee A, Martin M, Koren G, Cohen AR. Survival in medically treated patients with homozygous beta-thalassemia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:574–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409013310903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Sanctis V, Soliman AT, Elsedfy H, Skordis N, Kattamis C, Angastiniotis M, Karimi M, Yassin MA, El Awwa A, Stoeva I, Raiola G, Galati MC, Bedair EM, Fiscina B, El Kholy M. Growth and endocrine disorders in thalassemia: The international network on endocrine complications in thalassemia (I-CET) position statement and guidelines. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:8–18. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.107808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Suppl 1):S8–S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Sanctis V, Soliman AT, Elsedfy H, Albu A, Al Jaouni S, Yaarubi SA, Anastasi S, Canatan D, Di Maio M, Di Maio S, El Kholy M, Karimi M, Khater D, Kilinc Y, Lum SH, Skordis N, Sobti P, Stoeva I, Tzoulis P, Wali Y, Kattamis C. The ICET-A Survey on Current Criteria Used by Clinicians for the Assessment of Central Adrenal Insufficiency in Thalassemia: Analysis of Results and Recommendations. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2016 Jul 1;8(1):e2016034. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2016.034. doi: 10.4084/ MJHID. 2016.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuen KC, Tritos NA, Samson SL, Hoffman AR, Katznelson L. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Disease State Clinical Review: Update on growth hormone stimulation and proposed revised cut-point for the glucagon stimulation test in the diagnosis of adult growth hormone deficiency. Endocr Pract. 2016;22:1235–1244. doi: 10.4158/EP161407.DSCR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanis JA, Melton LJ, Christiansen C, Johnston CC, Khaltaev N. The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:1137–1141. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, Ishihara O, Mansour R, Nygren K, Sullivan E, Vanderpoel S. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1520–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization: Report of the meeting on the prevention of infertility at the primary health care level. WHO, Geneva 1983, WHO/ MCH/ 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franken DR, Oehninger S. Semen analysis and sperm function testing. Asian J Androl. 2012;14:6–13. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neto F, Bach P, Najari B, Li P, Goldstein M. Spermatogenesis in humans and its affecting factors. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;59:10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evenson D. Sperm Chromatin Structure Assay (SCSA®). In Spermatogenesis. Methods in Molecular Biology (Methods and Protocols) In: Carrell D, Aston K, editors. Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA; 2013. pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fibach E, Dana M. Oxidative Stress in β-Thalassemia. Mol Diagn Ther. 2019;23:245–261. doi: 10.1007/s40291-018-0373-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tremellen K. Oxidative Stress and Male Infertility – A Clinical Perspective. Hum Reproduct Update. 2008;14:243–258. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carpino A, Tarantino P, Rago V, De Sanctis V, Siciliano L. Antioxidant capacity in seminal plasma of transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemic patients. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2004;112:131–134. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-817821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elsedfy H, De Sanctis V, Ahmed AY, Mohamed NR, Arafa M, Elalfy MS. A pilot study on sperm DNA damage in β-thalassemia major: is there a role for antioxidants. Acta Biomed. 2018;89:47–54. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i1.6836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Sanctis V, Perera D, Katz M, Fortini M, Gamberini MR. Spermatozoal DNA damage in patients with β thalassaemia syndromes. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2008;6(Suppl 1):185–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Sanctis V, Borsari G, Brachi S, Govoni M, Carandina G. Spermatogenesis in young adult patients with beta-thalassaemia major long-term treated with desferrioxamine. Georgian Med News. 2008;156:74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perera D, Pizzey A, Campbell A, Katz M, Porter J, Petrou M, Irvine DS, Chatterjee R. Sperm DNA damage in potentially fertile homozygous beta-thalassaemia patients with iron overload. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1820–1825. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.7.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singer ST, Killilea D, Suh JH, Wang ZJ, Yuan Q, Ivani K, Evans P, Vichinsky E, Fischer R, Smith JF. Fertility in transfusion-dependent thalassemia men: effects of iron burden on the reproductive axis. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:E190–192. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soliman A, Yassin M, El-Awwa A, Osman M, De Sanctis V. Acute effects of blood transfusion on pituitary gonadal axis and sperm parameters in adolescents and young men with thalassemia major: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:638–643. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Sanctis V, Candini G, Giovannini M, Raiola G, Katz M. Abnormal seminal parameters in patients with thalassemia intermedia and low serum folate levels. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2011;8(Suppl 2):310–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Sanctis V, Soliman AT, Elsedfy H, Di Maio S, Canatan D, Soliman N, Karimi M, Kattamis C. Gonadal dysfunction in adult male patients with thalassemia major: an update for clinicians caring for thalassemia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2017;10:1095–1106. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2017.1398080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gaudio A, Morabito N, Catalano A, Rapisarda R, Xourafa A, Lasco A. Pathogenesis of Thalassemia Major-Associated Osteoporosis: Review of the Literature and Our Experience. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2018 Jul 11 doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.galenos.2018.2018.0074. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allard HM, Calvelli L, Weyhmiller MG, Gildengorin G, Fung EB. Vertebral Bone Density Measurements by DXA are Influenced by Hepatic Iron Overload in Patients with Hemoglobinopathies. J Clin Densitom. 2018 Jul 11 doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2018.07.001. pii: S1094-6950(17)30285-8.doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Sanctis V, Soliman AT, Elsefdy H, Soliman N, Bedair E, Fiscina B, Kattamis C. Bone disease in β thalassemia patients: past, present and future perspectives. Metabolism. 2018;80:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kyriakou A, Savva SC, Savvides I, Pangalou E, Ioannou YS, Christou S, Skordis N. Gender differences in the prevalence and severity of bone disease in thalassaemia. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2008;6(Suppl 1):116–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galanello R, Piras S, Barella S, Leoni GB, Cipollina MD, Perseu L, Cao A. Cholelithiasis and Gilbert’s syndrome in homozygous betathalassemia. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:926–928. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bini EJ, McGready J. Prevalence of gallbladder disease among persons with hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. Hepatology. 2005;41:1029–1036. doi: 10.1002/hep.20647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Inati A, Noureldine MA, Mansour A, Abbas HA. Endocrine and bone complications in β-thalassemia intermedia: current understanding and treatment. Biomed Res Int 2015. 2015:813098. doi: 10.1155/2015/813098. doi: 10.1155/2015/813098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baldini M, Marcon A, Cassin R, Ulivieri FM, Spinelli D, Cappellini MD, Graziadei G. Beta-thalassaemia intermedia: evaluation of endocrine and bone complications. Biomed Res Int 2014. 2014:174581. doi: 10.1155/2014/174581. doi: 10. 1155/2014/174581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Sanctis V, Tangerini A, Testa MR, Lauriola AL, Gamberini MR, Cavallini AR, Rigolin F. Final height and endocrine function in thalassaemia intermedia. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 1998;11(Suppl 3):965–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]