Abstract

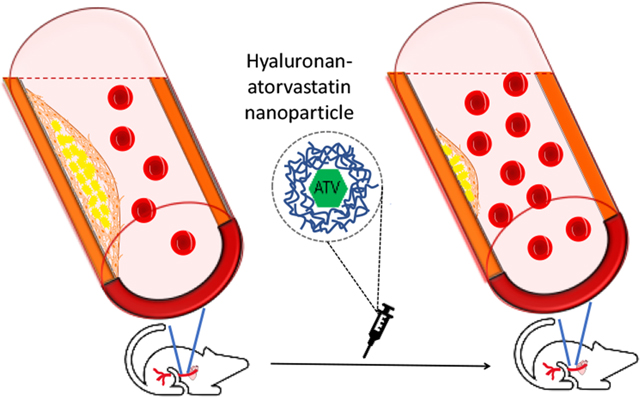

Atherosclerosis is associated with inflammation in the arteries, which is a major cause of heart attacks and strokes. Reducing the extent of local inflammation at atherosclerotic plaques can be an attractive strategy to combat atherosclerosis. While statins can exhibit direct anti-inflammatory activities, the high dose required for such a therapy renders it unrealistic due to their low systemic bioavailabilities and potential side effects. To overcome this, a new hyaluronan (HA) - atorvastatin (ATV) conjugate was designed with the hydrophobic statin ATV forming the core of the nanoparticle (HA-ATV-NP). The HA on the NPs can selectively bind with CD44, a cell surface receptor overexpressed on cells residing in atherosclerotic plaques and known to play important roles in plaque development. HA-ATV-NPs exhibited significantly higher anti-inflammatory effects on macrophages compared to ATV alone in vitro. Furthermore, when administered in an apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-knockout mouse model of atherosclerosis following a 1-week treatment regimen, HA-ATV-NPs markedly decreased inflammation in advanced atherosclerotic plaques, which were monitored through contrast agent aided magnetic resonance imaging. These results suggest CD44 targeting with HA-ATV-NPs is an attractive strategy to reduce harmful inflammation in atherosclerotic plaques.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory condition in the arteries. The rupture of atherosclerotic plaques is a major cause of heart attacks and strokes,1 which threatens the lives of more than 1.2 million Americans per year.2 As local inflammation is a significant risk factor for plaque rupture,3 reducing plaque inflammation is an attractive therapeutic strategy to reduce atherothrombotic events.1

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors known as statins are widely prescribed medicines that can decrease adverse cardiac events by 30%. While statins can reduce serum levels of cholesterol, they have other beneficial pleiotropic effects including anti-inflammatory activities by inhibiting inflammatory cells.4, 5 In apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-knockout mouse, a common model for human atherosclerosis development, although statins did not affect serum lipid levels even at a very high dose (100 mg/kg body weight), reduced plaque formation was observed in these mice suggesting antiatherosclerotic activity of statins beyond their plasma cholesterol-lowering functions.6 However, in humans, such high doses are not feasible due to the low bioavailability of statins entering the systemic circulation resulting from an extensive first pass effect at the liver as well as the potential adverse side effects such as musculoskeletal and liver toxicity at such doses.7–10 Therefore, strategies to deliver statins to inflammatory atherosclerotic plaques can be a potential strategy for atherosclerosis treatment.

Recently, high-density lipoprotein nanoparticles (HDL-NPs) loaded with a statin (simvastatin) have been developed using human apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I), which can mimic the native HDL particles in the body, accumulate in plaque tissues and locally deliver the statin.11 In an intensive treatment regimen (HDL-NPs at 60 mg/kg body weight simvastatin and 40 mg/kg ApoA-I, four injections per week) of ApoE knockout mice, inflammation in atherosclerotic plaques was markedly reduced, highlighting the potential of this approach. However, ApoA-I is expensive ($309/0.5 mg from Sigma) possibly hindering the wide applications of HDL-NPs. As an alternative, we investigate the utility of the readily available hyaluronan (HA) as the scaffold to deliver statins by targeting the CD44 receptor.

CD44 is a cell adhesion receptor expressed on the surface of major cell types present in the atherosclerotic plaques, including vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, macrophages and T cells.12–15 Multiple studies have suggested that CD44 promotes atherosclerosis by mediating inflammatory cell recruitment and vascular cell activation.13, 16, 17 In both ApoE knockout mice13, 17 and humans,12, 18, 19 the levels of CD44 expression present in rupture-prone regions of atherosclerotic plaques were over 10 times higher than that in healthy vascular tissues.20 The elevated CD44 expression in these unstable plaque sites render it an appealing target for targeted delivery.

The major endogenous ligand for CD44 in the body is hyaluronan (HA), a naturally existing polysaccharide with high biocompatibilities. The interactions of HA and CD44 have been utilized for atherosclerotic plaque studies.21, 22 However, to the best of our knowledge, CD44 has not been investigated as a drug delivery target for atherosclerosis treatment. Herein, we report our results on designing new HA nanoparticles (NPs) capable of delivering high quantities of statin per particle to reduce atherosclerotic plaque associated inflammation, which may in turn improve plaque stabilities.

Materials

Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), formalin solution neutral buffered 10%, fetal bovine serum (FBS), Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), anti-CD44 antibody [MEM-85] and Amberlite® IR 120 hydrogen form (Amberlite H+), pyridine p-toluenesulfonate, 2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl chloride, 4-(dimethylamino) pyridine, 4-methylmorpholine, 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine, Pd(OH)2/C, lipopolysaccharide and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Goat anti human IgG FC γ and centrifugal filter MWCO (10 kDa) were purchased from EMD Millipore. 2-Chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (CDMT) and N-methylmorpholine (NMM) were purchased form Acros Organics. Sodium hyaluronan (30 kDa) was obtained from Lifecore Biomedicals. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), LysoTracker-594 DND and TURBO DNA-free™ Kit were purchased from Invitrogen. Penicillin-Streptomycin (Pen Strep) mixture, trypsin-EDTA (0.5%), Power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix and L-glutamine were obtained from Thermo-Fisher. Recombinant human CD44 Fc chimera protein was acquired from R&D Systems®. RNeasy® Mini Kit was ordered from QIAGEN®. dNTP Mix, GoScript™ Reverse Transcriptase, Random Primers and CellTiter 96 Aqueous One solution containing 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxy-methoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) were purchased from Promega. Anti-CD44 antibody [KM81] and polyclonal rabbit anti-CD44 antibody were purchased from Abcam. Rat anti-F4/80 antibody was purchased from Biorad. Atorvastatin was purchased from AstaTech Inc. APC anti-mouse/human CD44 Antibody was purchased from BioLegend. S-2-(4-Isothiocyanatobenzyl)-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (p-SCN-Bn-DTPA) was purchased from Macrocyclics™.

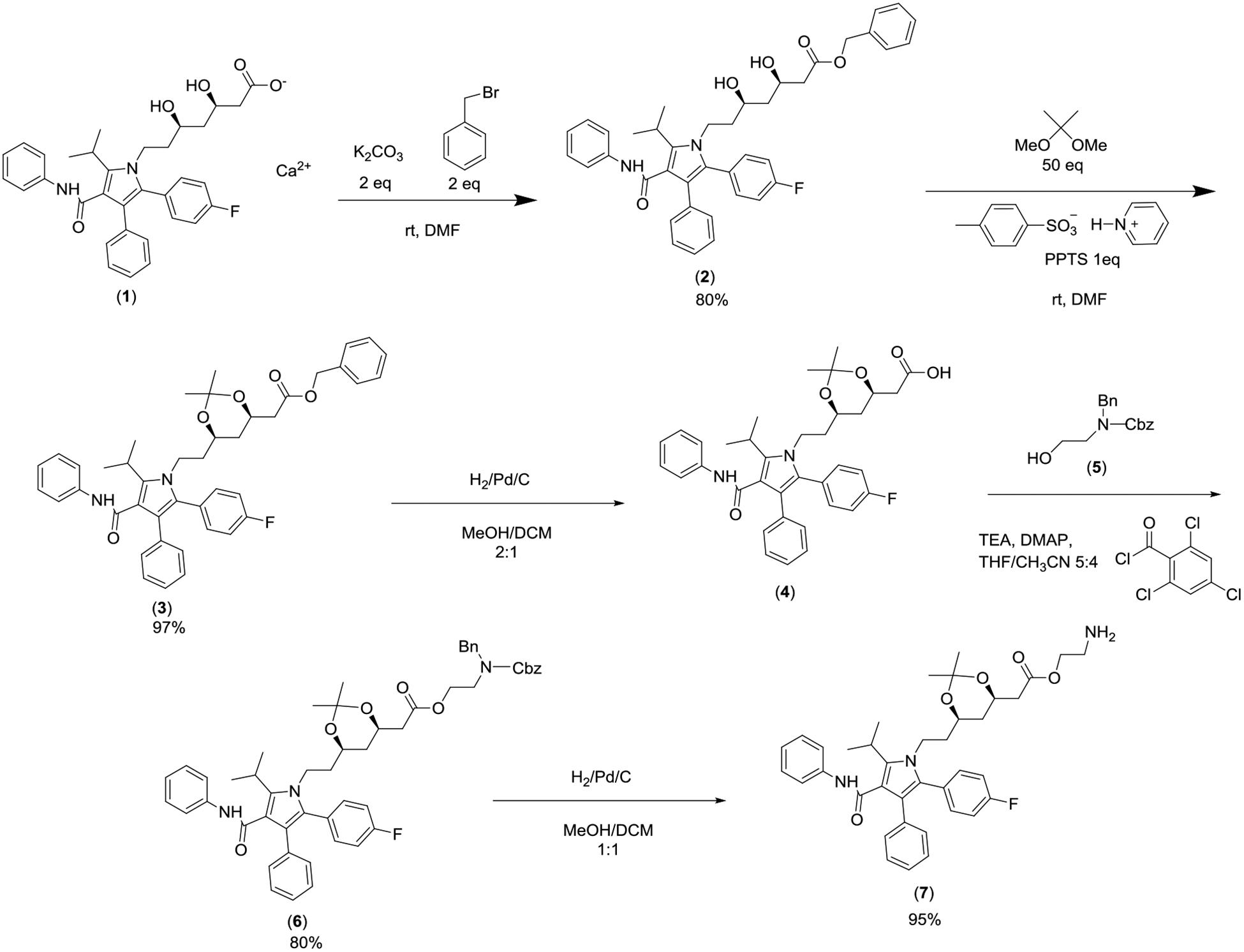

Synthesis of HA-ATV NP

Atorvastatin calcium salt 1 (3 g, 5.4 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (20 mL), then potassium carbonate (1.48 g, 10.7 mmol) and benzyl bromide (1.28 mL, 10.7 mmol) were added and stirred for 3 hours at room temperature. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate and washed by sodium chloride solution (1 M). The resulting product 2 was purified by silica gel column chromatography and obtained in 80% yield as a white solid. Thereafter, compound 2 (2.6 g, 4.1 mmol) was dissolved in DMF and 2,2-dimethoxypropane (24.9 mL, 200 mmol) and pyridine p-toluenesulfonate (PPTS) (1.02 g, 4.7 mmol) were added and stirred for 8 hours at room temperature and the isopropylidine bearing product 3 was purified in 97% yield by silica gel column chromatography. Next, the benzyl ester group of 3 was removed through catalytic hydrogenations by adding Pd/C (0.83 7.8 mmol) to a solution of 3 (2.7 g, 3.9 mmol) in methanol/dichloromethane (2:1, 10 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred under H2 gas for 30 min. After the reaction was completed, it was filtered and concentrated to give compound 4, which was used without further purification for the next step. To a solution of 4 (2.43 g, 4.1 mmol) in anhydrous acetonitrile (20 mL), triethylamine (0.57 mL, 4.1 mmol), 2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl chloride (0.64 mL, 4.1 mmol) and 4-(dimethylamino) pyridine (0.5 g, 4.1 mmol) were added. A solution of N-protected ethanolamine 5 (1.16 g, 4.1 mmol) in anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (5 mL) was added to the reaction mixture and stirred for 1 hour. After completion, the reaction mixture was quenched with water (1 mL), concentrated in vacuo and the residue was purified by silica gel chromatography to afford the product 6 in 80% yield. Finally, the Cbz group on the amine in 6 was removed using Pd/C under a hydrogen atmosphere in a mixture of methanol/dichloromethane (1:1) leading to the aminated ATV analog 7, which was obtained in 95% yield after purification with silica gel chromatography. 1H NMR (500 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 7.23 – 7.14 (m, 8H), 7.07 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.03 – 6.97 (m, 3H), 6.87 (s, 1H), 6.56 (q, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H, NH), 4.17 (dddd, J = 11.7, 7.2, 4.3, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 4.08 (ddd, J = 14.5, 9.8, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (ddd, J = 14.5, 9.7, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 3.70 (q, J = 5.2 Hz, 3H), 3.58 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 3.46 – 3.35 (m, 2H), 2.33 (qd, J = 14.9, 5.9 Hz, 2H), 1.71 – 1.59 (m, 4H), 1.54 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.53 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.38 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.34 (s, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (126 MHz, chloroform-d) δ 171.49, 164.80, 163.23, 161.26, 141.44, 138.32, 134.54, 133.19, 133.12, 130.46, 128.75, 128.67, 128.36, 128.23, 128.20, 126.58, 123.55, 121.79, 119.58, 115.46, 115.32, 115.29, 98.96, 66.37, 66.17, 62.33, 43.06, 42.24, 40.77, 37.93, 35.78, 29.93, 26.07, 21.75, 21.58, 19.75. HRMS: C38H45FN3O5 [M+H]+ calcd: 642.3338, obsd: 642.3391.

To prepare the HA-ATV conjugate, HA was first protonated with Amberlite H+ resin, then dissolved in a mixture of water/acetonitrile (3:2).23 Subsequently, 4-methylmorpholine (1.2 eq) and 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (0.4 eq) were added and stirred for 30 minutes. Then, ATV-amine 7 (0.4 eq) was dissolved in a mixture of acetonitrile/DMSO (1:3), added to HA solution and stirred for 36 hours at room temperature. Next, the reaction mixture was transferred to a dialysis bag (MWCO: 3 kDa) and dialyzed against PBS (3 times, each time 12 hours against 2 L at 4 °C) and distilled water (3 times, each time 12 hours against 2 L at 4 °C). The mixture was dried using a freeze dryer.

To prepare HA-ATV NP, HA-ATV (8 mg/mL) was first dissolved in DMSO. The solution was added dropwise to Milli-Q water (15 mL) via a syringe (needle size G30) over 15 minutes with stirring speed of 500 rpm. Subsequently, the mixture was transferred to a dialysis bag (MWCO: 3 kDa) to wash off residue DMSO. Dialysis was performed 6 times, every 12 hours in distilled water (2 L) at 4 °C. The HA-ATV NPs formed were characterized for hydrodynamic size and zeta potential using a dynamic light scattering (DLS) Zetasizer Nano zs apparatus (Malvern, U.K.). Moreover, particle concentration and particle size were analyzed using ZetaView® (Particle Metrix, Germany).

To prepare FITC labeled HA-ATV-NP, FITC (1 mg) was dissolved in HA-ATV solution in DMSO (7 mg/ 1 mL) and stirred overnight. For this reaction, FITC most likely reacted with the hydroxyl group of HA through its isothiocyanate moiety. The FITC labelled HA-ATV NPs were formed following the same protocol as described above in reaction vessels wrapped with aluminum foil to reduce photobleaching of FITC. Next, FITC labelled HA-ATV NPs were washed by dialysis (MWCO: 3 kDa) to remove free FITC. Dialysis was performed every 12 hours in distilled water (2 times) and PBS (4 times) against 2 L of solution at 4 °C. Finally, the FITC-HA-ATV NPs were concentrated using a centrifugal filter (MWCO: 10 kDa) and stored at 4 °C.

Electrophoresis of HA-ATV Conjugate

Agarose gel (0.8 %) was prepared through dissolving agarose (0.96 gram) in hot water (108 mL). The tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer (10x, 12 mL) was added. Then, HA (7 μg) and HA-ATV NP (11.7 μg) were placed on the gel and electrophoresis was performed at 150V for 1 hour. Next, the gel was stained using a freshly prepared Stains-All dye solution (0.005%) in 50% ethanol solution and was kept in dark overnight. Finally, the gel was destained in the dark using 20% ethanol solution until HA spots appeared on the gel.

HA-ATV NP Binding with CD44 by ELISA

Each well of a 96 well plate was incubated with a solution of goat anti human IgG FC γ containing 3μg antibody dispersed in PBS (100 μL).23 The plate was kept at 4 °C overnight while sealed to prevent evaporation. The wells were then washed with 200 μL of PBST solution (0.5% Tween 20) 3 times (1 minute for each wash). Thereafter, microplate wells were incubated with a BSA solution (5% w/v) for 2 hours at 37 °C to block non-specific binding. Then, wells were washed 3 times using PBST solution (0.5% Tween 20, 1 minute for each wash). After the last wash, the wells were incubated with 100 μL of CD44 Fc chimera solution (0.2 μg/well, in PBS) for 45 minutes at 37 °C. Next, wells were washed 3 times (1 minute for each wash) by PBST solution (0.05% Tween 20, 200 μL) and wells were incubated with various concentrations of HA-ATV NP (0.06, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 μg/mL, at 100 μL each) containing 2.5 μg biotinated HA (b-HA) for 2 hours at room temperature. Subsequently, wells were washed 3 times using PBST solution (0.05 % Tween 20, 200 μL) and 2 times with PBS solution (1 minute for each wash). Then, freshly prepared avidin-horseradish peroxidase solution (1:2000 diluted in 0.2% BSA, 100 μL) was added to each well and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Thereafter, wells were washed 3 times using the PBST solution (0.05 % Tween, 200 μL) and 2 times with PBS solution (1 minute for each wash). Then, chromogenic TMB solution (100 μL) was added to each well for 15 minutes until a blue color was developed. Finally, the reaction was quenched by adding 0.5 M H2SO4 solution (50 μL) and the absorbance at 450 nm wavelength was measured by a SpectraMax M3 plate reader.

HA-ATV NP Uptake by RAW264.7 Cells

Cellular uptake of HA-ATV NP by CD44 expressing cells RAW264.7 was examined by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis at 4 °C and 37 °C. Cells were cultured in a 6-well plate in the presence of 5% CO2 at 37 °C until they became confluent. Then, fresh media containing various concentrations of FITC labeled HA-ATV NP (33, 66 and 99 μg/mL) were added and the cells were further incubated for 1 hour. Thereafter, the medium was removed, and cells were washed with PBS. Next, cells were detached by trypsin followed by the addition of 5 volume of medium to neutralize the trypsin. Then, cells were centrifuged, resuspended in DMEM and transferred to FACS tubes for analysis.

After cellular uptake of FITC labeled HA-ATV NPs, the cells were imaged by confocal microscopy. RAW264.7 cells (2 × 105 cells/mL) were dispersed in DMEM containing FBS (10%) and allowed to grow on a cover glass placed in each well of a 6-well plate overnight. Then, the medium was removed and serum free DMEM containing FITC labeled HA-ATV NP (33 μg/mL) was incubated with cells for 1 hour. Subsequently, lysotracker red (1 μM) was added to each well and incubated for another 1 hour at 37 °C. Then, cells were washed 3 times by PBS and 10% formalin solution neutral buffered (1 mL) was added for 15 minutes. After fixation, cells were washed by PBS buffer 3 times and a DAPI solution (300 nM, 500 μL) was added and incubated for 5 minutes. Then, cells were washed 3 times using PBS and the cover glass was placed over a microscope slide containing anti-fade solution and images were collected on a Nikon C2 confocal microscope.

In another experiment, ATV uptakes by RAW264.7 cells were quantified by 19F-NMR as follows. RAW264.7 cells (1.5 × 108) were incubated with ATV (0.25 mg/mL) and HA-ATV NP (at equivalent amount of ATV) and dispersed in DMEM containing FBS 10% for 40 minutes. Then cells were thoroughly washed to remove unbound ATV or NPs. Thereafter, a NaOH solution (1 M, 100 μL) was added and the mixture was kept at 100 °C for 20 minutes to release ATV from NPs. Next, a SDS (1%) solution in DMSO (400 μL) was added and the supernatant was collected after centrifuge and the 19F-NMR spectra of each sample were acquired. The amounts of ATV taken up in the cells were determined from the ratios of integration compared to an internal standard, 4,4ʹ-difluorobenzophenone.

Evaluating the Role of HA for Cellular Uptake of HA-ATV NP

RAW264.7 cells were cultured in a 6-well plate in the presence of 5% CO2 at 37 °C until complete confluency was reached. Free HA (10 mg/mL) was added to the medium and after 30 minutes FITC labeled HA-ATV NP (33 μg/mL) was added and incubated for another 45 minutes. Subsequently, the medium was removed. Cells were washed with PBS (3 times) and trypsin was added to detach the cells. Then, 5 volume of DMEM was added to neutralize trypsin. Cells were collected by centrifuge (1600 rpm, 5 minutes) and dispersed in DMEM for FACS analysis.

Assessing the Role of CD44 for Uptake of HA-ATV NP in CD44 Expressing Cells

In a 96-well plate, RAW264.7 cells were cultured until confluency. Then, cells were fixed by addition of neutral buffered 10% formalin solution and they were washed by PBS 3 times using centrifugation. Subsequently, KM81 antibody (60 μg/mL) was added to the fixed cells dispersed in PBS buffer for 1 hour. Then, cells were sedimented by centrifugation to remove unbound antibody and incubated with FITC labeled HA-ATV NP (33 μg/mL) for another 1 hour. Finally, cells were washed with PBS and their fluorescence intensities were measured using a plate reader.

Detection of Intracellular ATV Delivered by HA-ATV NP

It has been shown that ATV becomes fluorescent after UV light exposure.24 A solution of HA-ATV NP was kept under UV light (254 nm) for 48 hours. Excitation and emission wavelengths were measured as a reference using a spectrophotometer SupraMax. RAW264.7 cells (2 × 105 cells/mL) were dispersed in DMEM containing FBS (10%) and allowed to grow on a cover glass placed in each well of a 6-well plate overnight. Then, the medium was removed and serum free DMEM containing UV-irradiated HA-ATV NP (33 μg/mL) was incubated with cells for 1 hour. Then, cells were washed 3 times by PBS and formalin solution neutral buffered 10% (1 mL) was added and incubated for 15 minutes. After fixation, cells were washed by PBS buffer 3 times and the cover glass was placed over a microscope slide containing anti-fade solution to prevent sample drying. Images were gathered on a Nikon C2 confocal microscope.

ATV Release from HA-ATV NP Promoted by a Hyaluronidase

To a solution of HA-ATV NP (5.2 mg in 8 mL PBS buffer) in a dialysis bag (MWCO: 3 kDa), was added hyaluronidase (0.55mg, from Sigma, H3506) dissolved in PBS buffer (1 mL). The dialysis bag was placed in a beaker containing PBS buffer (40 mL) at 37 °C and the UV absorbance (λ=250 nm) of the solution was measured at various time intervals with the amounts of ATV plotted against time. For the standard, solutions of ATV in PBS buffer containing DMSO (8 %) with various ATV concentrations (3.12, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 μg/mL) were prepared and the UV absorbance values at 250 nm were measured to generate the standard curve. As a control, samples were incubated in an identical manner with the exception that hyaluronidase was not added to the solution. The total amount of ATV in HA-ATV NP sample was quantified by 19F-NMR. For this purpose, HA-ATV conjugate was dissolved in a mixture of DMSO-d6/D2O (2:3) and the ratios of integration compared to the internal standard, 4,4ʹ-difluorobenzophenone, were determined.

Evidence for ATV Release from Diol Protected Derivative 4 of ATV under an Acidic Condition

The diol protected form of ATV derivative 4 (5 mg) was dissolved in PBS buffer (12 mL) containing 40% DMSO and the pH was brought to 5 by dropwise addition of acetic acid. The solution was checked 0.5 hour and 3 days later and the formation of acid hydrolysis products were verified using ESI mass spectrometry (Figure S11).

Viability of RAW264.7 Cells Following Incubation with HA-ATV NP

RAW264.7 cells were dispersed in DMEM cell culture media containing FBS (10%) and cultured in a 96-well plate in the presence of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Then, cells were incubated with various concentrations of ATV and HA-ATV NP (56 and 112 μM) for 4 hours. The media was removed, and MTS reagent dispersed in medium (10%) was added and incubated for another 2 hours until the color was developed. The absorption of each well was measured at 490 nm using a SpectraMax M3 plate reader.

Anti-inflammatory Effects of HA-ATV NP

Mouse macrophage cells (RAW264.7) were used to study the anti-inflammatory effects of HA-ATV NP in vitro. Cells (2 × 105 /well) were dispersed in DMEM medium supplemented with FBS (10%) and Pen Strep (1%) and cultured overnight in a 6-well plate in the presence of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Then, the medium was removed and FBS free medium containing HA-ATV NP was added and incubated for 15 hours. Subsequently, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was added to each well to reach the final concentration of 100 ng/mL and incubated for another 4 hours. Then, the medium was removed, cells were washed with PBS (2 times) and total RNA content of each well was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit. Immediately, the extracted RNA was purified using a TURBO DNA-free Kit, quantified by NanoDrop and stored at −80 °C. cDNA was prepared from purified RNA and used for real time PCR. All the primers for this experiment as shown in Table 1 were purchased from IDT. In addition to the inflammatory genes, the level of inducible nitric oxide synthase iNOS was quantified in RAW264.7 cells. For this experiment, cells were treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 1 hour and then HA-ATV NP was added and incubated for 23 hours. The cellular RNA content was extracted and the expression level of iNOS was quantified by rt-PCR.

Table 1.

Primer sequences of inflammatory genes for rt-PCR study

| Gene | forward primer (5´ → 3´) | reverse primer (5´ → 3´) |

|---|---|---|

| TNFα | CAGGCGGTGCCTATGTCTC | CGATCACCCCGAAGTTCAGTAG |

| IL-1b | TTCAGGCAGGCAGTATCACTC | GAAGGTCCACGGGAAAGACAC |

| IL-1α | CGAAGACTACAGTTCTGCCATT | GACGTTTCAGAGGTTCTCAGAG |

| ICAM-1 | GTGATGCTCAGGTATCCATCCA | CACAGTTCTCAAAGCACAGCG |

| iNOS | GTTCTCAGCCCAACAATACAAGA | GTGGACGGGTCGATGTCAC |

Therapeutic Evaluation of HA-ATV NP in Vivo

Mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and were kept in the University Laboratory Animal Resources Facility of Michigan State University. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Michigan State University and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Michigan State University.

For this experiment, 20-week old ApoE knockout mice were fed with a high fat Western diet (TD.88137 Harlan Laboratories) for 6 weeks. The presence of inflammatory atherosclerotic plaques was confirmed through T2-weighted MRI using HA-NWs following established procedures.21 Then, HA-ATV NP (8.5 mg ATV per kg animal body weight) was administered to each mouse intravenously every other day for one week (total 4 doses). As a control, PBS solution (100 μL) was administered to the control group of mice. In addition, ATV (8.5 mg/kg) was administered orally through an oral gavage to mice every other day for one week. Mice were sacrificed, and their aortas were harvested for further histology studies.

Histology Study

Harvested aortas were soaked in 30% sucrose solution overnight. Then, samples were fixed in a freshly prepared formalin solution, processed and embedded in paraffin. Subsequently, aorta samples were sectioned using a rotary microtome and placed on glass slides and dried at 56 °C overnight. The slides were subsequently deparaffinized in xylene then descending grades of ethyl alcohol to distilled water were used to hydrate the samples. Next, slides were placed in Tris Buffered Saline (pH=7.4) (Scytek Labs – Logan, UT) for 5 minutes for pH adjustment. Subsequently, sample pretreatment was performed using proteinase K (2%) in TE buffer (pH=8) at room temperature for 3 minutes. Then, the samples were washed several times in distilled water and endogenous peroxidase was blocked utilizing hydrogen peroxide/methanol (3%) bath for 30 minutes followed by multiple water rinses. Next, standard micro-polymer complex staining steps were performed at room temperature on the IntelliPath™ Flex Autostainer. All staining steps are followed by rinses in TBS autowash buffer (Biocare Medical – Concord, CA). After blocking for non-specific protein with Mouse Block (Biocare) for 5 minutes; sections were incubated with rat anti-F4/80 antibody (1:100) in normal antibody diluent (NAD-Scytek) for 60 minutes. Micro-Polymer (Biocare) reagents were subsequently applied for specified incubations (15 minutes probe, 15 minutes polymer) followed by reaction development with Romulin AEC™ (Biocare) for 5 minutes and counterstained with Cat Hematoxylin (1:10) for one minute.

For CD44 staining, samples were processed as mentioned above until pH adjustment in TBS buffer (pH=7.4). Heat Induced Epitope Retrieval in Citrate Plus (pH=6.0) (Scytek) was performed in a vegetable steamer at 100 °C for 30 minutes, followed by 10-minute room temperature incubation and rinses with several changes of distilled water. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked utilizing 3% hydrogen peroxide/methanol bath for 30 minutes followed by running tap and distilled water rinses. Following pretreatments, standard micro-polymer complex staining steps were performed at room temperature on the IntelliPath™ Flex Autostainer. All staining steps are followed by rinses in TBS autowash buffer (Biocare Medical – Concord, CA). After blocking for non-specific protein with Rodent Block M (Biocare) for 20 minutes; sections were incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-CD44 antibody (1:400) in normal antibody diluent (NAD-Scytek) for 60 minutes. Micro-Polymer (Biocare) reagents were subsequently applied followed by reaction development with Romulin AEC™ (Biocare) for 5 minutes and counterstained with Cat Hematoxylin (1:10) for one minute.

Mice treated with HA-ATV NPs or PBS (controls) were euthanized 24 hours after the last injection via gas anesthesia followed by cervical dislocation. Liver, lung, kidney, spleen, heart, pancreas, and testicle were harvested from all mice, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5 μm thick sections. The tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain, and evaluated by a board-certified veterinary pathologist.

In vivo Imaging

The mice were scanned on 7T MRI before and after retro-orbital injections of HA coated magnetic nanoworms (HA-NWs) following reported protocols.21 The abdominal aorta was serially scanned until the aortic lumen signal intensities returned to the pre-injection value. Magnetic resonance experiments were performed on all mice anesthetized by 1.5% isoflurane following an induction using 4% isoflurane. Animals were secured in the supine position and restrained to reduce imaging artifacts due to motion. A Bruker 4-channel surface array was placed beneath the mouse to image the upper portion of abdominal aorta then placed in the isocenter of a Bruker 70/30 7 Tesla horizontal bore imaging spectrometer. Serial images were acquired using the following acquisition parameters: TE/TR=8/174 ms, in-plane resolution = 0.1 × 0.1 mm2, slice thickness = 0.8 mm, Flip Angle = 50 deg, Number of Acquisition (NA) = 16. The TE and NA were selected to obtain good imaging contrast within a reasonable amount of time, i.e., around 6 minutes per acquisition.

Biodistribution Study

99mTc labeled HA-ATV NP (5 mCi/kg body weight) was administered intravenously to ApoE knockout mice (n= 3) as well as wild type mice (n=3). The 99mTc level in each syringe was measured in a dose calibrator (CRC-24R, Capintec,Inc.) before and after injection for precise quantification of administered doses. Animals were euthanized two hours after injection. The organs (liver, kidney, spleen, heart, aorta, bone, and lung) were collected, weighed, and the 99mTc levels were measured using a calibrated gamma counter (Wizard 2480, Perkin Elmer). Following decay correction to injection time, and conversion of counts per minute to microcuries, the % of injected dose per gram of tissue was calculated.

RESULTS

Synthesis and Characterization of HA-ATV-NPs

For drug delivery, the ability to deliver high drug loading per particle is highly desirable. One common strategy is to immobilize the target drug or cargo on the surface of NPs. However, the amount of drug per particle that could be surface loaded was relatively low. For example, with our previously synthesized HA coated NPs,25–27 the cargo doxorubicin accounted for only 2.1% by weight of the NPs. To enhance drug delivery capabilities, the new design here takes advantage of the hydrophobic nature of the cargo, i.e., atorvastatin (ATV). Upon conjugation of ATV with HA, the resulting amphiphilic polymer could self-assemble into NPs in aqueous solutions with ATV as the hydrophobic core.

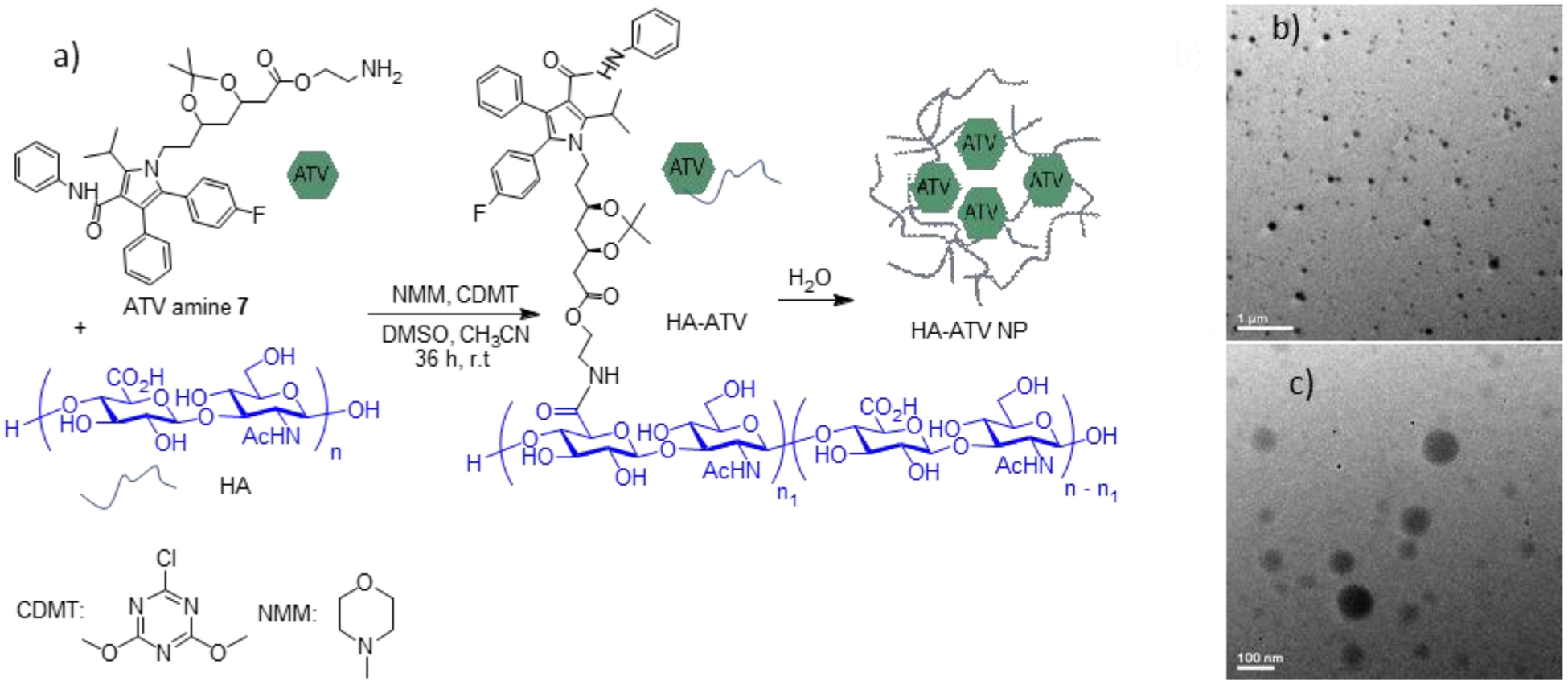

In order to conjugate HA with ATV, ATV 1 was first benzylated followed by conversion to isopropylidene protected carboxylic acid 4, which was then esterified by the N-protected ethanolamine 5 and subsequently hydrogenated to yield ATV amine 7 (Figure 1). The conjugation of amine 7 with HA (30 kDa) was mediated by 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (CDMT) with N-methylmorpholine (NMM) as the base (Figure 2). Upon removal of free ATV through extensive dialysis, the successful conjugation of HA with ATV was confirmed by NMR analysis as signals from both ATV and HA were observed in its 1H-NMR spectrum in DMSO-d6 (Figure S5). The average number of ATV per HA disaccharide was determined to be 0.4, which corresponded to 35% w/w of the total mass of the conjugate being ATV. The HA-ATV was subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with Stains-All dye. Previously, we showed that HA-bearing iron oxide nanoparticles can move through the agarose gel.21 As shown in Figure S6, HA-ATV migrated slower than pure HA on agarose gel. In addition, pure HA stained blue with the Stains-All dye, while HA-ATV appeared purple with the same stain, further confirming the successful conjugation of HA with ATV and the complete removal of free HA.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of aminated ATV derivative 7 for HA conjugation.

Figure 2.

Preparation of hyaluronan conjugated atorvastatin (HA-ATV) NP. (a) Conjugation of HA with ATV. (b and c) TEM images of prepared HA-ATV NPs in water. Scale bars are 1 μm and 100 nm respectively.

Upon mixing with water, HA-ATV formed NPs due to its amphiphilic nature. The hydrodynamic diameter of HA-ATV NP was 122 nm in water (and 132 nm in PBS buffer) as determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS). The zeta potentials of HA-ATV NP were −35 and −17 mV in water and PBS buffer respectively, suggesting the presence of negatively charged carboxylic groups on the surface of the HA-ATV NPs. The morphology of the prepared HA-ATV NPs was spherical as indicated by TEM (Figures 2b, c). Interestingly, when 1H-NMR of HA-ATV NP was acquired in D2O, only signals from HA were observed (Figure S7). This is most likely because ATV aggregated in the core of HA-ATV NP, resulting in significant ATV signal broadening in NMR. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis showed that each mg of HA-ATV NP contains 5.9 × 1010 particles on average, which corresponds to 6.4 × 106 molecules of ATV per NP.

To test the stability of HA-ATV NPs in aqueous solutions, a freshly prepared HA-ATV NP sample was dissolved in PBS buffer and serially diluted. The number of particles and the size of NPs for each diluted sample were measured by ZetaView®. No significant changes were observed for the size of NPs after dilution (Figure S18). These data suggest that the HA-ATV NPs in aqueous solution remain as particles at even in very diluted samples, and it is likely HA-ATV NPs maintain their particle forms in vivo.

The HA-ATV NPs have high stabilities for storage, as there were little changes in the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of the prepared NPs in water for two weeks at 4 °C (Figure S8). In another experiment, HA-ATV NPs prepared in water were freeze-dried and stored at −20 °C for 5 months. Addition of water to this freeze-dried powder regenerated HA-ATV NPs with similar hydrodynamic diameters and zeta potential values as the freshly prepared NPs (Figure S9).

The release of ATV from HA-ATV NP was investigated next. As hyaluronidase is abundant in atheromatous plaques,28 HA-ATV NP was treated with this enzyme. As shown in Figure S10, ATV could be released from HA-ATV NPs with a half-life of 30 hours. In contrast, much less ATV was found in the solution without the addition of a hyaluronidase (Figure S10). Furthermore, isopropylidene protected ATV derivative 4 was dissolved in buffer with pH 5, which is the typical pH encountered in lysosomes. The isopropylidene moiety of 4 was almost completely cleaved from the molecule within 3 days (Figure S11). These results combined suggest the active form of ATV could be released from HA-ATV NPs.

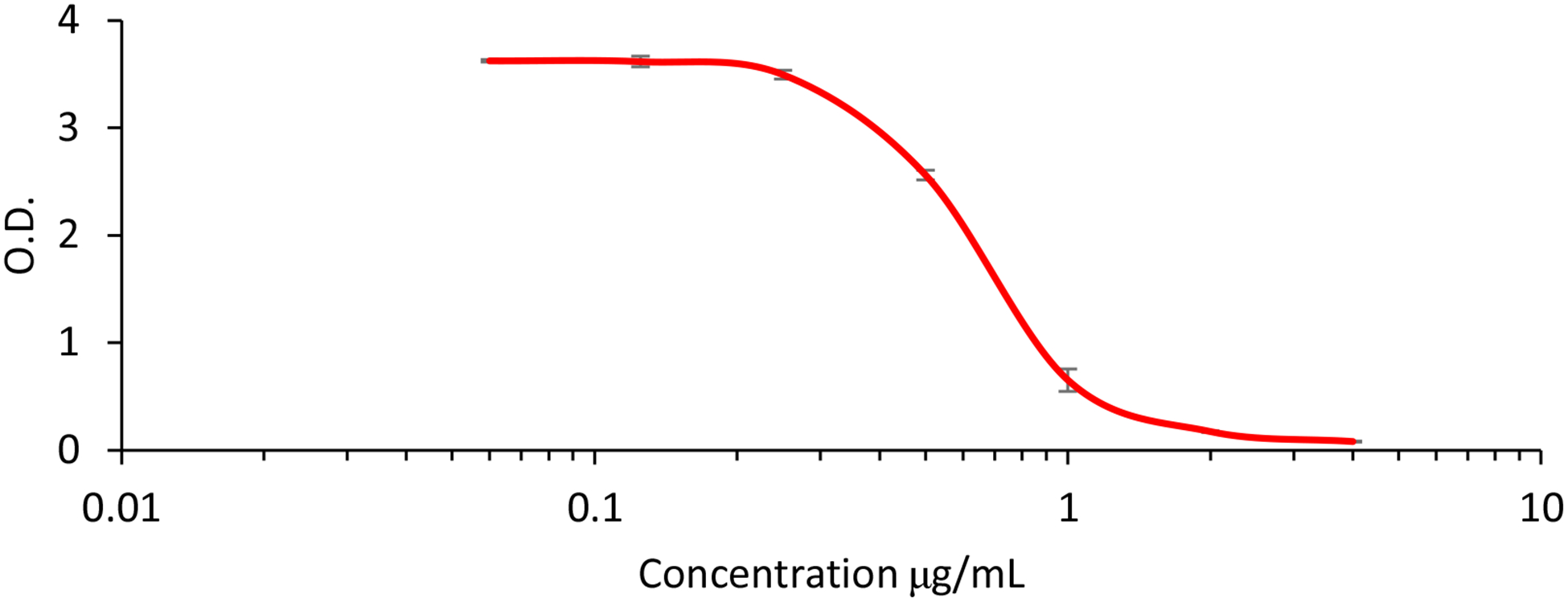

HA-ATV NPs Retained the Ability to Bind with CD44 Receptor

The abilities of HA-ATV NP to bind with CD44 were analyzed next using a competitive enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).23 In this experiment, biotinated HA was bound with CD44 immobilized in ELISA wells, to which increasing concentrations of HA-ATV NPs were added. If HA-ATV NP could bind with CD44, it would displace biotinated HA from CD44 resulting in reduced ELISA signals. As shown in Figure 3, HA-ATV NPs exhibited dose dependent inhibition of biotinated HA binding with CD44 with an apparent EC50 value of 0.45 μg/mL. This indicates that HA-ATV NPs retain the ability of HA to bind with CD44.

Figure 3.

Competitive ELISA experiments confirmed the CD44 binding ability of HA-ATV NP. In the ELISA, biotinated HA was co-incubated with increasing concentrations of HA-ATV NP in ELISA wells coated with CD44 protein. If HA-ATV NP could bind with immobilized CD44, it would compete with biotinated HA binding with CD44 resulting in the decrease of optical density (O.D.) in the well when detected with the avidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate. HA-ATV NP was able to compete with free HA for CD44 binding with an apparent EC50 value of 0.45 μg/mL.

HA-ATV NPs Could Be Taken Up by Macrophages, Which Was Favored at 37 °C over 4 °C

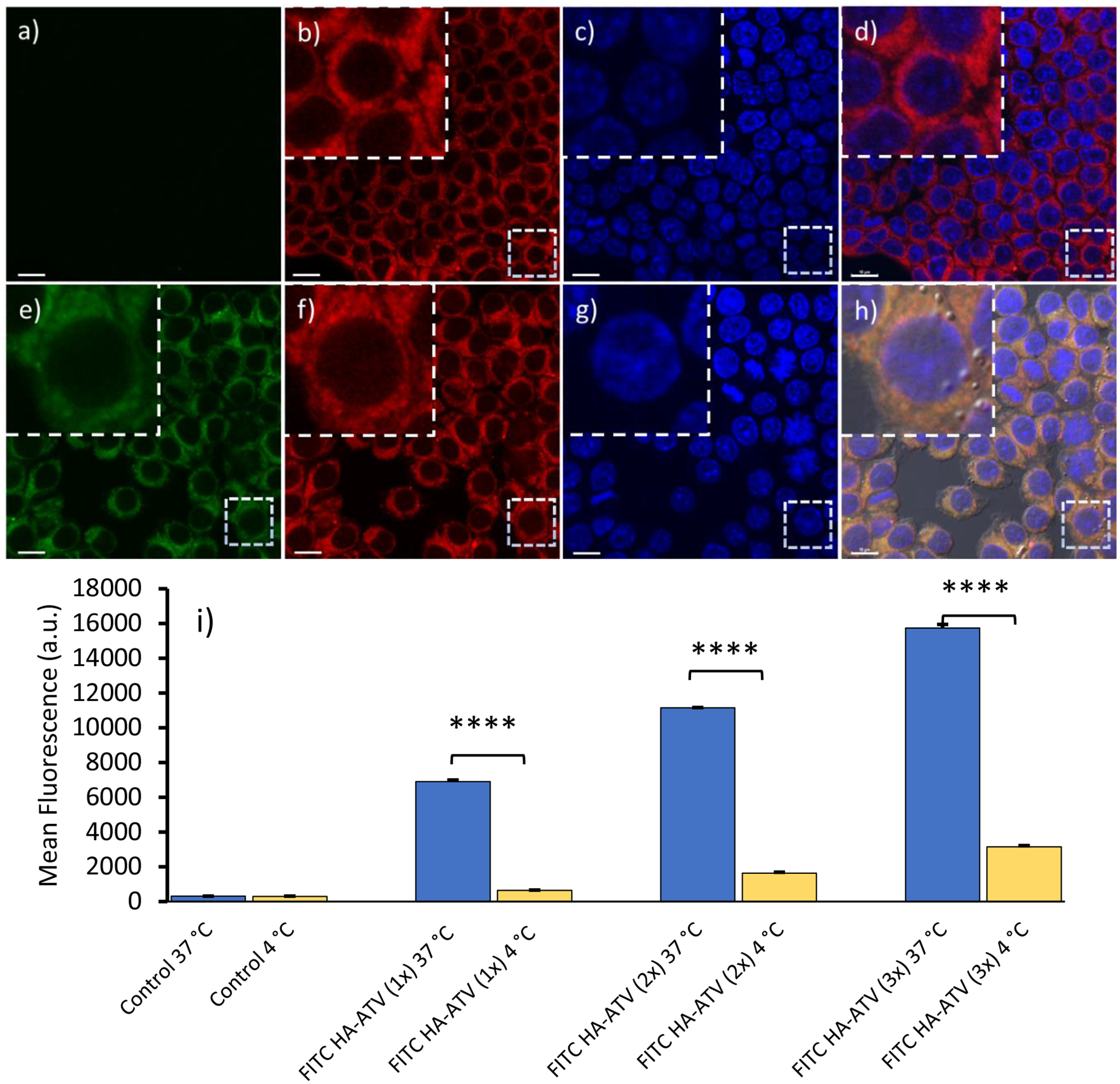

With the ability of HA-ATV NPs to bind with CD44 established, their interactions with CD44 expressing mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells were investigated. The expression of CD44 in this cell line was confirmed through confocal imaging with an anti CD44 mAb (Figures S19). HA-ATV NPs were labeled with the fluorophore fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), incubated with macrophage RAW264.7 cells and analyzed. Confocal microscopy of cells following incubation with FITC labelled HA-ATV NP showed strong green fluorescent signals inside the cells when incubated at 37 °C. The green fluorescence was found mainly in the cytoplasm and co-localized well with the red fluorescence from lysotracker, indicating internalization of NPs and their accumulation in the cytoplasm (Figures 4a–h). Dose dependent increase of cellular uptake was observed which was quantified by FACS (Figure 4i). The levels of cellular uptake were much higher at 37 °C vs those at 4 °C, suggesting the interactions with RAW264.7 cells were significantly reduced at a lower temperature (Figure 4i and S19 f–o). The cells were imaged after incubation with HA-ATV NPs for 2, 8 and 24 hours and an increase of fluorescence intensities was observed in the cells with a longer incubation time (Figure S19 p–s), which was consistent with the FACS data (Figure 4i). In separate experiments, several potential endocytosis inhibitors including dynasore, β-cyclodextrin, and chlorpromazine were added individually to cells before incubation with HA-ATV NPs. None of the inhibitors reduced the levels of HA-ATV uptake (data not shown), suggesting the uptake was not through clathrin mediated endocytosis or caveolae-mediated endocytosis.

Figure 4.

Cellular uptake of FITC HA-ATV NP by RAW264.7 cells. Confocal microscopy of RAW264.7 cells indicates FITC HA-ATV NPs end up in cytoplasm of the cells. (a-d) shows RAW264.7 cells only; and (e-h) are RAW264.7 cells after incubation with FITC HA-ATV NPs. Images from FITC, Red Lysotracker and DAPI channels are (a,e), (b,f) and (c,g) respectively. (d and h) are overlays of FITC, Red Lysotracker and DAPI channels. Scale bars are 10 μm. (i) Cellular uptake of FITC HA-ATV NPs is dose dependent as determined by FACS analysis of RAW264.7 cells after incubation with increasing doses of FITC HA-ATV NP. Incubation at 37 °C led to higher binding compared to that at 4 °C. Statistical analysis was performed using student t test. **** < 0.0005

To directly detect ATV inside the cells, HA-ATV NPs were irradiated by UV (λmax = 254 nm), which is known to result in a shift of ATV emission maximum from 350 nm into blue region 430 nm due to intramolecular photocyclization and the formation of phenanthrene ring in ATV (Scheme S1).24 RAW264.7 cells were imaged after treatment with UV irradiated HA-ATV NPs. Stronger blue fluorescence was observed in the cytoplasm compared to non-treated cells confirming that ATV cargo was successfully delivered inside the cells (Figure S12).

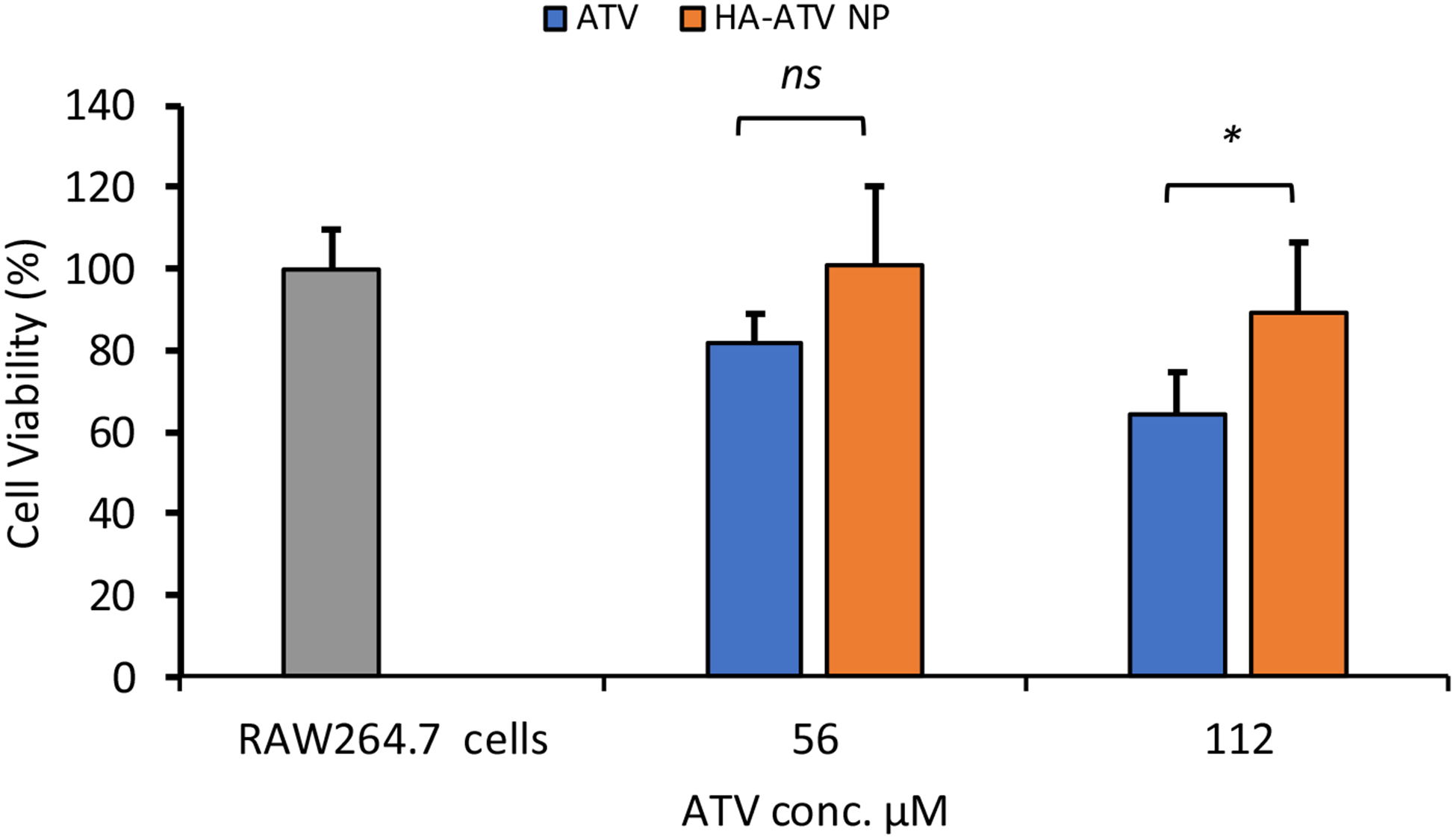

In order to quantify ATV uptake by RAW264.7 cells, 19F-NMR spectra of cell lysate following treatment with ATV or HA-ATV NP were acquired (Figure S13). 19F-NMR signals from ATV were observed in RAW264.7 cells confirming the cellular uptake of ATV. Integrating ATV signals against an internal standard enabled quantification of ATV, which showed 40% higher amounts of ATV in cells when cells were treated with HA-ATV NP than those receiving the free drug. MTS cell viability assay was performed next to measure the viability of RAW264.7 cells following incubation with different concentrations of ATV and HA-ATV. As shown in Figure 5, HA-ATV NP did not impact the viability of macrophages much at the concentrations studied (up to 112 μM ATV/mL) after 4 hour incubation.

Figure 5.

Viability of RAW264.7 cells following incubation with free ATV or HA-ATV NP at equivalent ATV concentrations for four hours as determined by the MTS cell viability assay. Statistical analysis was performed using student t test. * p < 0.05. ns: not significant.

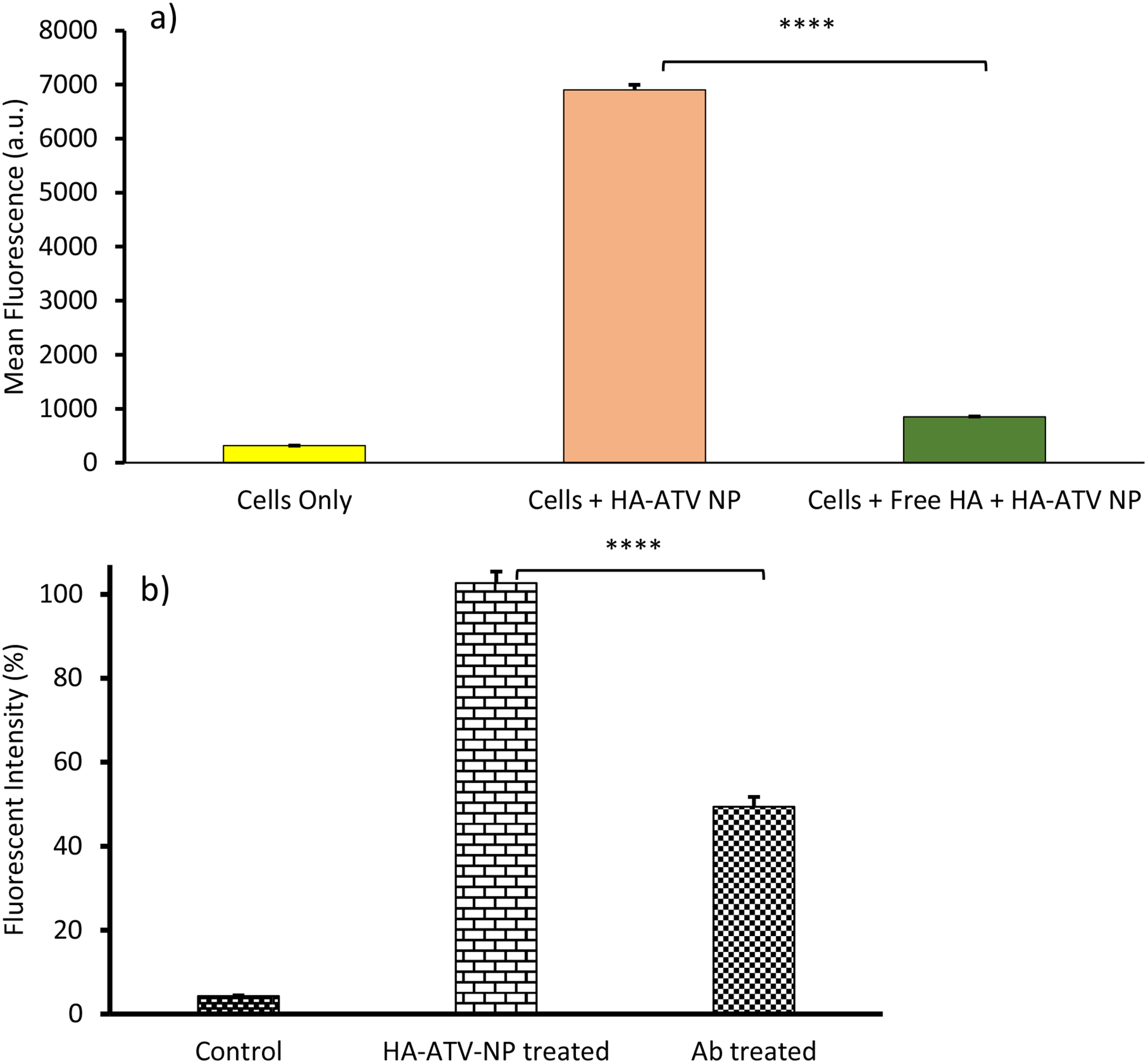

Both HA and CD44 Play Important Roles in Cellular Interactions with HA-ATV NPs

To better understand HA-ATV NP interactions with macrophages, RAW264.7 cells were incubated with FITC labeled HA-ATV NP in the presence of free HA in a competitive binding experiment.29, 30 Free HA significantly reduced (91%) the levels of HA-ATV NP binding with the cells suggesting the interactions were HA dependent (Figure 6a). Furthermore, pretreatment of RAW264.7 cells with an anti-CD44 monoclonal antibody KM81 caused a 50% reduction of the cellular interactions with HA-ATV NP (Figure 6b). This is consistent with the idea that CD44 plays important roles in HA-ATV NP interactions with macrophages.

Figure 6.

Cellular interactions with HA-ATV NP are HA and CD44 dependent. (a) Mean fluorescence intensities of RAW264.7 cells incubated with HA-ATN NP (33 μg/mL), and HA-ATV NP (33 μg/mL) with free HA (10 mg/mL). Addition of free HA significantly reduced cellular binding by HA-ATV NP. (b) Pre-incubation of RAW264.7 cells with anti-CD44 monoclonal antibody KM81 reduced 50% binding by HA-ATV NP to RAW264.7 cells. The mean fluorescence intensity of cells incubated with HA-ATV NP was set as 100%. The % of relative fluorescence intensity was calculated by dividing the mean fluorescence intensity of cells incubated with KM81 and HA-ATV-NP by that from cells incubated with HA-ATV-NP only. Statistical analysis was performed using student t test. * p < 0.0005.

HA-ATV NP Reduces the Inflammatory Activities of Macrophages in Vitro

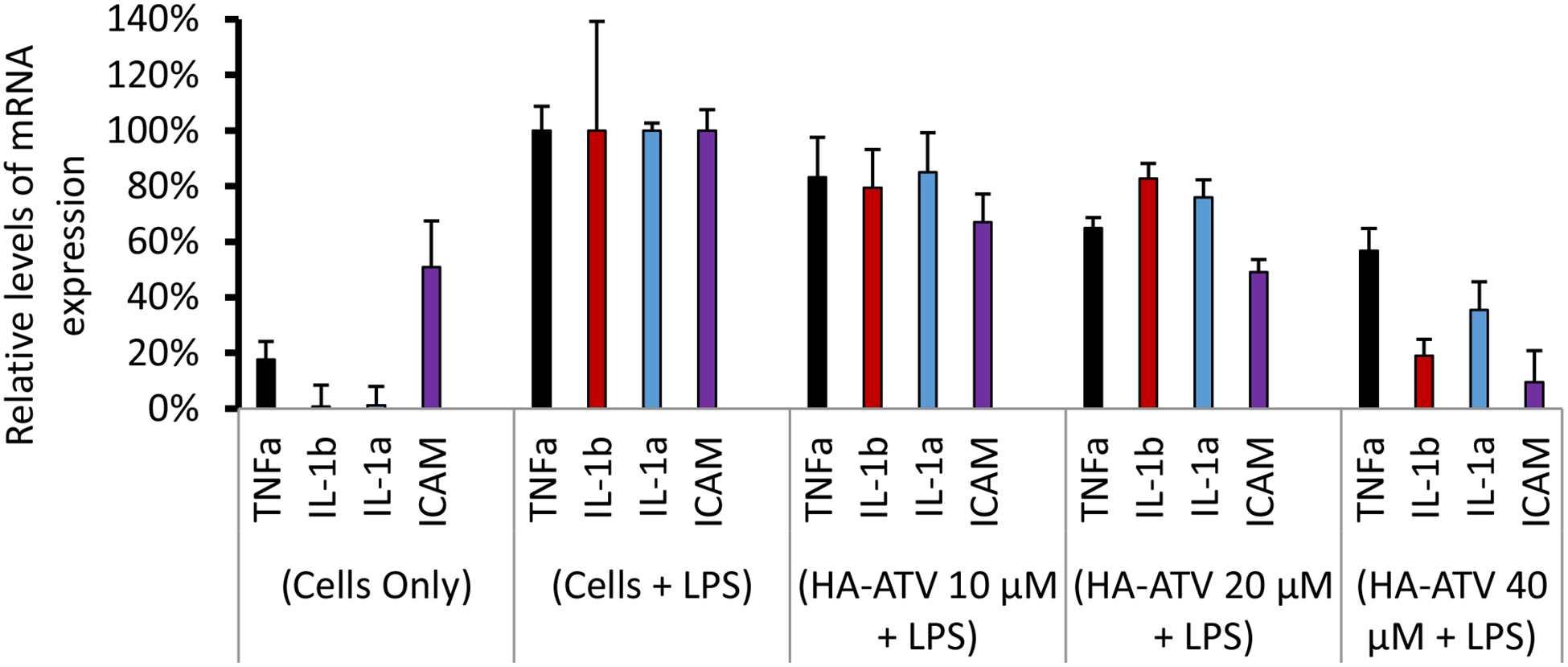

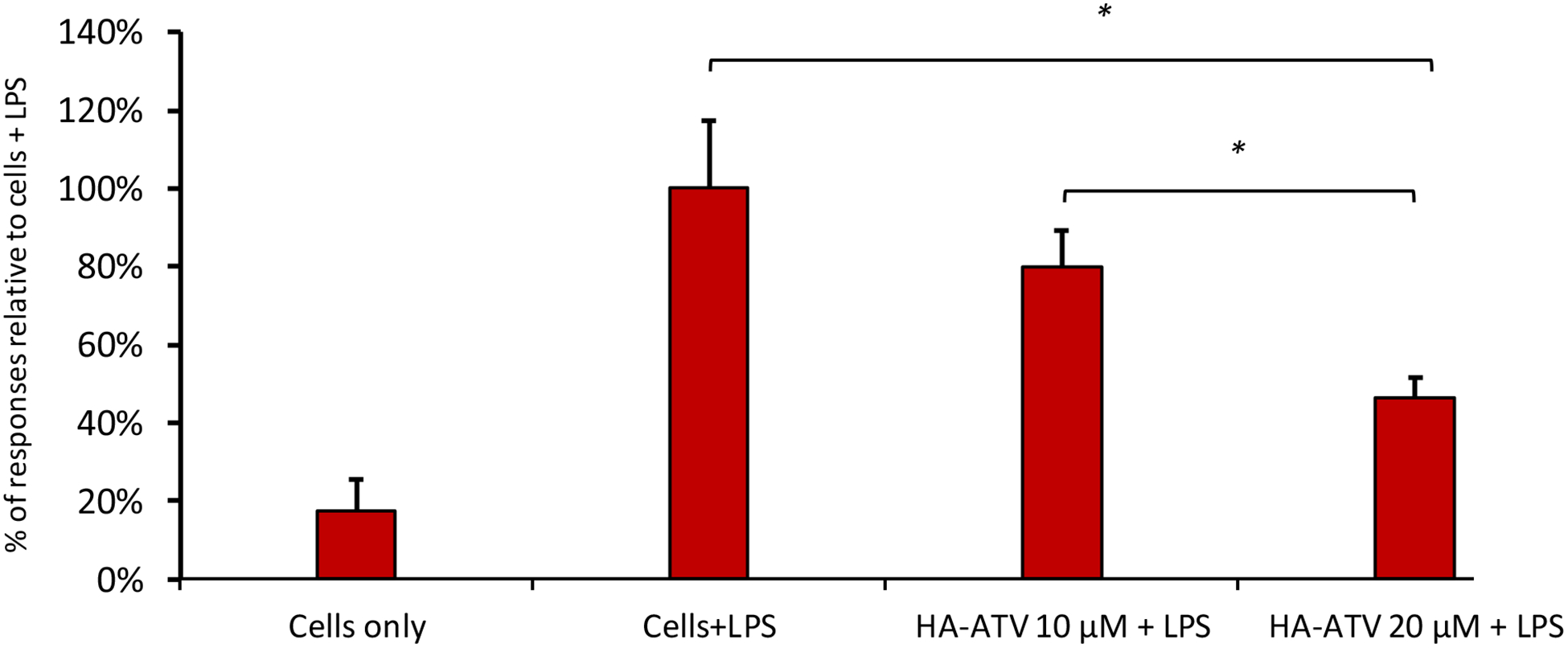

With the establishment of binding and uptake of HA-ATV NPs by macrophages, their impacts on inflammatory activities were assessed. RAW264.7 cells were incubated with HA-ATV NPs followed by LPS. LPS is known to stimulate Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) in macrophages, leading to the production of a wide range of molecules associated with inflammation including TNFα, IL-1β, IL-1α and ICAM-1. Control cells received free form of ATV, free HA or a mixture of free ATV and HA at equivalent doses. The expression levels of inflammatory genes in the cells were quantified by rt-PCR. Interestingly, while neither free ATV nor free HA decreased the levels of inflammatory genes in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells (Figure S14), HA-ATV NPs reduced TNFα, IL-1β, IL-1α and ICAM-1 levels by 45%, 81%, 65% and 95% respectively highlighting the importance of having both HA and ATV (Figure 7). When a mixture of free HA and ATV was added to the RAW264.7 cells, low levels of cytokines were also observed (Figure S17a). However, this was most likely due to cell death, as the cell viability when incubated with a mixture of HA and ATV for 19 hours was much lower than cells treated with HA-ATV NPs (Figure S17b). It is known that inflammatory cytokines can induce the production of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS),31 contributing to the inflammatory process of plaque development.32 Inhibition of iNOS can mitigate atherosclerosis through impairing foam cell migration and cholesterol influx.33, 34 Consistent with the effect of HA-ATV NPs on inflammatory gene expression, a 55% reduction in iNOS levels was observed in RAW264.7 cells following HA-ATV NP and LPS incubation (Figure 8). The superior in vitro anti-inflammatory activities of HA-ATV NP set the stage for in vivo evaluations.

Figure 7.

Reduction of inflammatory gene expression levels in RAW264.7 cells following treatment with HA-ATV NP. Cells were treated with culture media (Cells only), LPS (Cells + LPS), or various concentrations (10 μM, 20 μM, and 40 μM respectively) of HA-ATV NP and LPS. The expression levels of mRNA corresponding to TNFα, IL-1β, IL-1α and ICAM were quantified by rt-PCR. The mRNA levels from cells + LPS group were set as 100%.

Figure 8.

HA-ATV NP decreased the expression levels of iNOS in LPS treated RAW264.7 cells. Cells were treated with culture media (Cells only), LPS (Cells+LPS), or various concentrations (10 μM or 20 μM respectively) of HA-ATV and LPS. The expression levels of iNOS mRNA were quantified by rt-PCR. The mRNA level from cells + LPS group was set as 100%. Statistical analysis was performed using student t test. * p < 0.05.

HA-ATV NP Decreased Atherosclerotic Plaque Inflammation in ApoE Knockout Mice

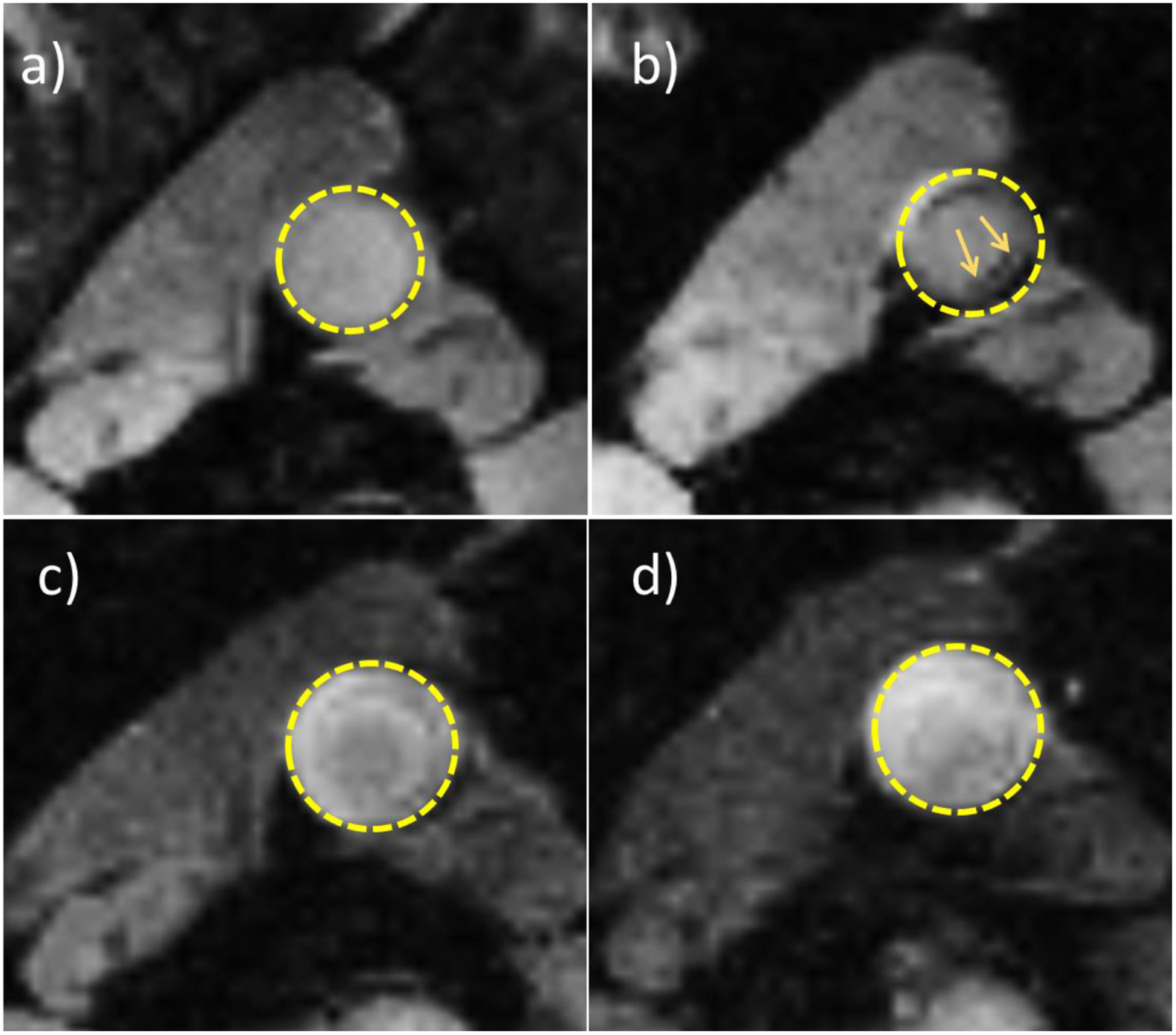

ApoE knockout mice are a clinically relevant model of atherosclerosis, as these mice spontaneously develop atherosclerotic plaques, which can be accelerated with a high fat diet.35 Previously, we developed HA coated magnetic nanoworms (HA-NWs), which could aid in the non-invasive detection of inflammatory atherosclerotic plaques by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).21 To test the efficacy of HA-ATV NP for atherosclerosis treatment, groups of ApoE knockout mice were fed with a high fat diet, and then subjected to HA-NW aided MRI. Consistent with our prior studies,21 six weeks after being on the high fat diet, ApoE knockout mice showed extensive signal loss on their aorta walls in the HA-NW aided T2* weighted MRI indicating the development of inflammatory atherosclerotic plaques (Figures 9a and b). These mice were then treated with HA-ATV NPs (4 intravenous injections every other day at the dose of 8.5 mg ATV/Kg body weight) and imaged again by MRI. The ATV dose was chosen based on prior work showing that ATV (~10 mg/kg) can induce anti-inflammatory effects in Apo-E mouse.36, 37 Interestingly, in contrast to untreated mice (Figure S15), T2* weighted images of aorta walls of HA-ATV treated mice no longer exhibited any signal losses suggesting greatly reduced accumulation of HA-nanoworms at plaque sites. These results indicate that HA-ATV NP treatment significantly decreased the degree of plaque inflammation.

Figure 9.

Atherosclerotic plaques were not detectable in ApoE knockout mouse aorta by MRI after HA-ATV NP treatment. (a) and (b) are representative T2* weighted MRI images of ApoE knockout mouse abdominal aorta before and after HA-NW injection, respectively. Arrows in b) show the areas of signal losses presumably due to HA-NW binding at inflammatory plaques. (c) and (d) are representative T2* weighted MRI images of mouse aorta one week later after receiving HA-ATV NP. (c) and (d) are before and after injection of HA-NW respectively.

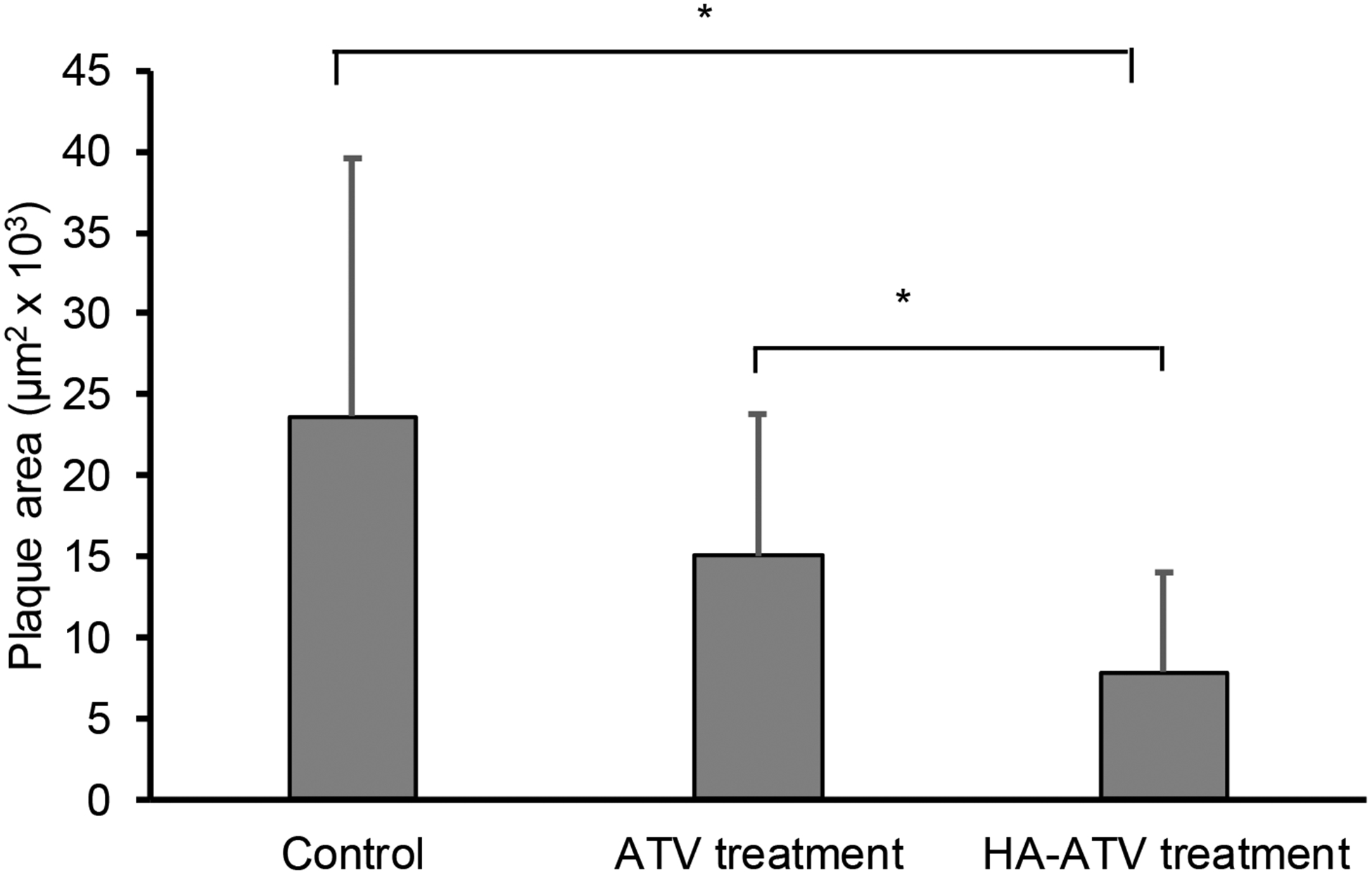

In order to confirm the observation in MRI, ApoE knockout mice were euthanized following HA-ATV NP treatment, and their aortas were extracted for histological studies. Another group of age matched mouse were administered with pharmaceutical grade ATV via oral gavage with the same dose of ATV and schedule as HA-ATV (ATV is poorly soluble in water, which cannot be administered directly via intravenous injection). F4/80 staining showed reduction in macrophage content of plaques in HA-ATV treated group compared to ATV group or untreated control (Figures S16a–c). Similar reduction in CD44 levels at plaques was observed in HA-ATV treated group (Figures S16d–f). Moreover, the areas of plaque were quantified, which were reduced by 69% in treated group compared to non-treated control group (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Plaque area quantification in abdominal aorta showed significant reduction in ApoE knockout mice group that received HA-ATV NP as compared to those receiving ATV or PBS only. ImageJ was used for plaque area measurement. There are 4 mice in each group and the areas of the plaques in the abdominal aorta and aortic arch were measured in multiple slices and averaged. The p-value was obtained using the ANOVA test. * p < 0.05.

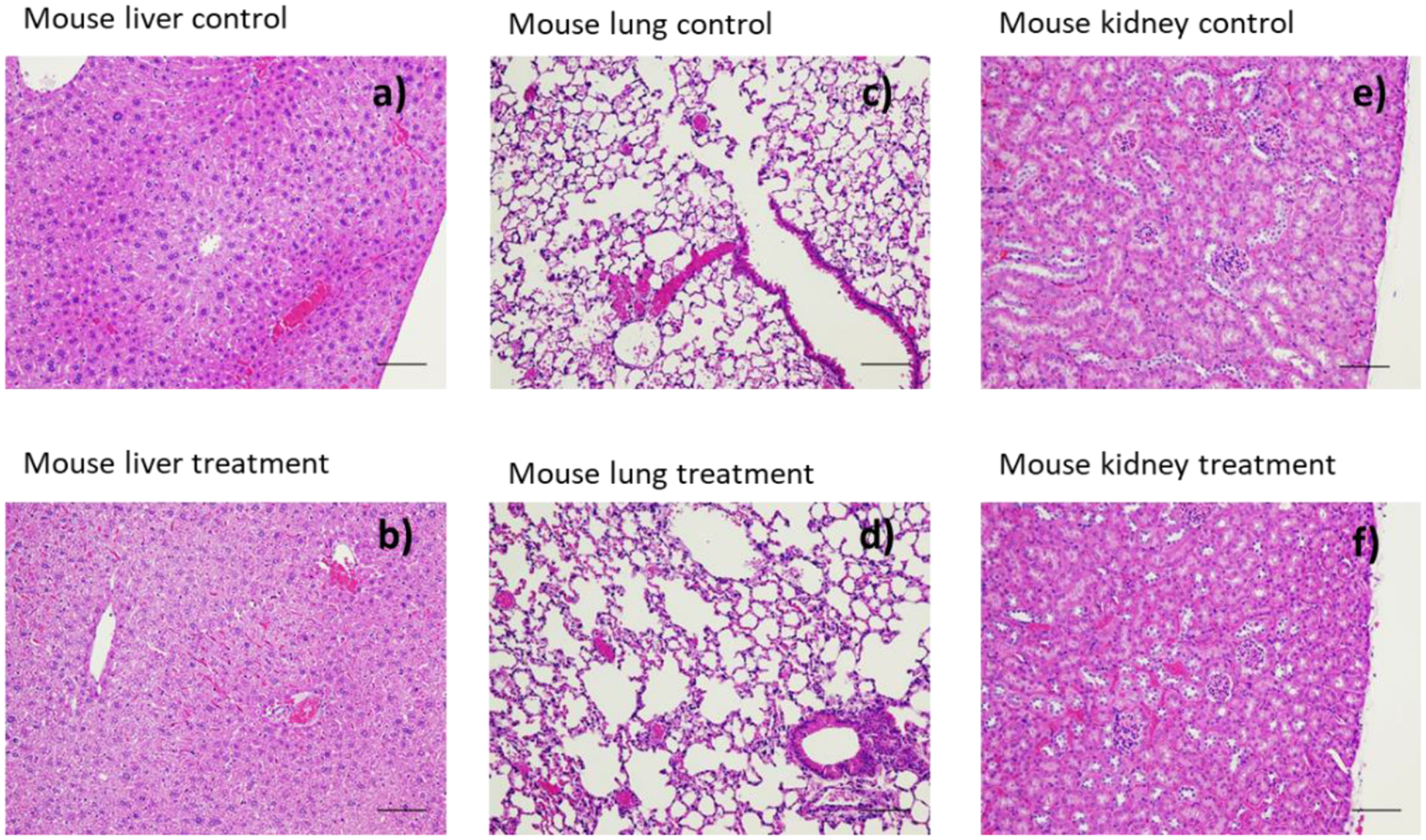

HA-ATV NP Treatment Showed no Toxicities from Histopathology Study of Mouse Tissues

Liver, lung, kidney, spleen, heart, pancreas, and testicle from mice treated with HA-ATV NPs were collected and compared with those from mice receiving PBS control only. Histopathology analysis of the tissues did not show any toxicities due to NP administration with representative images from liver, lung, and kidney shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Histopathology images of extracted organs after one-week treatment with HA-ATV NP. No significant differences were observed in these organs compared to those from control mice receiving PBS only: (a) mouse liver, (c) mouse lung tissue, (e) mouse kidney images from control mouse receiving PBS only; (b) mouse liver, (d) mouse lung, (f) mouse kidney from mice receiving HA-ATV NPs. Scale bar is 100 μm.

Biodistribution Study for 99mTc-labeled HA-ATV NP

To analyze the biodistribution of HA-ATV NPs in mice, 99mTc labeled HA-ATV NPs were synthesized by functionalizing HA-ATV NPs, the metal chelator diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) and subsequently radiolabeled with 99mTc. The resulting 99mTc HA-ATV NPs retained binding to CD44 as confirmed by the competitive ELISA in a similar manner as HA-ATV NP. ApoE knockout mice as well as normal mice were injected with 99mTc HA-ATV NPs intravenously. The highest retention was observed in the reticuloendothelial system organs such as liver and spleen (Figure S20a). About 1.7% of the injected dose of HA-ATV NP was found in aortas, which was higher than that found in aortas of normal mice (1.1%) (Figure S20b) suggesting higher uptake of NP by atherosclerotic plaques.

Discussion

Inflammation is a significant risk factor for the rupture of atherosclerotic plaques, which are a major cause of heart attack and stroke. The ability to reduce local inflammation at rupture prone plaque sites is an attractive approach to combat atherosclerosis associated mortality and morbidity, as global reduction of inflammation may adversely impact body’s abilities to fight infections. In order to accomplish targeted delivery to plaques, HA-ATV conjugate has been synthesized, which can self-assemble into HA-ATV NPs in water presumably by hydrophobic core formation through ATV moieties surrounded by the hydrophilic HA polymer. The HA-ATV NPs can be cleaved through enzymatic and acid promoted hydrolysis to release the active ATV ingredient. The HA-ATV NP utilized in the current study contained 35% of the total mass of conjugate as the active drug. This is significantly higher than the typical cargo loading levels when drugs are only loaded to the NP exterior (2.1% w/w of the cargo).25–27 Thus, utilizing ATV as the hydrophobic core markedly increased the amount of drug per particle with the covalent linkage between ATV and HA significantly reducing premature drug leakage (Figure S10). Moreover, this formulation not only is stable for two weeks at 4 °C, but also could be kept as freeze-dried powder at −20 °C for many months thus boding well for future translations.

HA-ATV NPs retained their CD44 binding property as evident from the competitive ELISA results (Figure 3). The interactions of HA-ATV NPs with RAW264.7 cells were shown to be highly HA dependent as high concentration of free HA can block cellular uptake of HA-ATV NP. Pre-incubation of RAW264.7 cells with an anti-CD44 mAb KM81 reduced 50% of the cellular interaction, which is consistent with the idea that the cellular interactions of HA-ATV NP are at least partially mediated by CD44 (Figure 6). Cellular interactions of HA-ATV were significantly reduced at 4 °C vs 37 °C suggesting HA-ATV NPs enter the cells more readily at a higher temperature (Figure 4i). Moreover, ATV quantification in RAW264.7 cells showed 40% higher cellular uptake when HA-ATV was used as compared to free ATV. In addition, MTS assay showed good biocompatibility of HA-ATV at the therapeutic doses used in this study (Figure 5). These results suggested HA-ATV NP as a superior construct compared to free ATV.

A key finding of our study is that the HA-ATV NP treatment of macrophage cells in vitro effectively inhibited inflammatory responses induced by LPS (Figures 7 and 8). Some HA and HA nanoparticles have been shown to exhibit anti-inflammatory activities.22, 38 For instance, Beldman et al. introduced a formulation of HA-NP that exhibited anti-inflammatory effect when administered once a week (50 mg HA /kg) for 3 months.22 In comparison, in the current study, HA-ATV NPs (~17 mg HA /kg) delivered ATV to the plaques, with one-week treatment already resulting in significant anti-inflammatory effects in plaques. The activities of HA-ATV NP were likely not due to the direct effects of HA since free HA was not active under the same condition as HA-ATV NP presumably due to the low concentration of HA and short duration of treatments (Figure S14). Importantly, at the same dose, free ATV did not exhibit much anti-inflammatory function either. Thus, it is critical to conjugate ATV with HA to suppress macrophage inflammatory responses without the need to wait extended periods of time before observing therapeutic effects.

Recruitment of inflammatory cells is a key process in atherosclerosis development, in which CD44 plays an important role.39 While CD44 is also present on cell surface under normal physiological conditions, it mainly exists in a low HA affinity state. During inflammation, the presence of inflammatory signals such as TNF-α induces sulfation of CD44, leading to conformational changes of the protein and resulting in its switch to high affinity state for HA binding.40 The binding of HA with CD44 on macrophages leads to the trafficking of macrophages to plaques, which exacerbates inflammation in plaque sites. The HA-ATV NPs can mimic this process by binding with CD44. This enables selective accumulation of NPs in plaques, and delivery of ATV to plaque sites.

An atherosclerosis mouse model was established with ApoE knockout mice. To monitor inflammation in plaques in vivo, mice were imaged by MRI aided by HA coated magnetic NWs. Upon feeding with a high fat diet for six weeks, mouse aortas exhibited significant signal losses in T2* weighted MRI suggesting marked inflammation in aorta walls (Figures 9a,b and S15). Following just one-week treatment with HA-ATV NPs, the MRI signal changes were no longer observed indicating the reduction of inflammation (Figure 9d). Histology analysis of treated mice confirmed that HA-ATV NPs led to a decrease of inflammation as reflected by lower macrophage content, CD44 level and sizes of the plaques, which supported the observations in MRI. The therapeutic effect was more pronounced with HA-ATV NPs than free ATV at the equivalent ATV dose (Figure 10). These results highlight that even with a relatively short one-week treatment regimen, significant benefits could be obtained using HA-ATV NPs. At the same time, our results confirmed that HA-NWs21 could be a useful non-invasive method to monitor efficacy of atherosclerosis treatment.

In general, drug delivery can be performed through either passive (diffusion of drugs into the desired site) or active targeting (binding with receptors present in plaques).41, 42 Active targeting can potentially improve the organ selectivity, enhance the percentage of drugs reaching plaque sites, and lower the dose needed.43 A strategy to actively target atherosclerotic plaques is to mimic the naturally existing HDL particles, as they are known to interact with atherosclerotic plaques through ApoA-1 binding with various receptors such as ABCA1, ABCG1, ecto-F1-ATPase and scavenger receptor B1 (SR-B1).44, 45 HDL NPs encapsulating simvastatin have been constructed, which can deliver simvastatin to plaques to achieve local anti-inflammatory effects.11 Compared to the untreated group, HDL-simvastatin NP at 60 mg/kg statin dose on one-week treatment regimen reduced plaque sizes as well as levels of inflammatory markers. While these studies demonstrated the effectiveness and feasibility of statin delivery for local inflammation reduction, the relatively high cost of HDL suggests other NP systems should be explored. With our HA-ATV NPs, we achieved superior in vivo efficacy compared to free ATV with the readily available HA (~ $100/g) for NP construction.

In addition to statin delivery, several other strategies have been investigated applying nanotechnology to reduce plaque burden. Recently, carbon nanotubes were designed to deliver a Src homology 2 domain-containing phosphatase-1 (SHP-1) inhibitor to restore phagocytic activity of macrophages in the plaques and reduce the atherosclerotic plaque sizes.46 In addition, promotion of cholesterol efflux from the plaque has been investigated through amphiphilic supramolecular nanostructures to deliver liver X receptor agonist GW3965 into the plaques.47 Our HA-ATV NPs can complement these technologies by delivering ATV to reduce inflammation.

In conclusion, we have synthesized a new type of NPs (HA-ATV NP) capable of delivering a large quantity of ATV per particle. The HA-ATV NPs can target inflammatory atherosclerotic plaques through CD44 receptor and release its payload. In addition, the NPs are more effective compared to free ATV in reducing inflammation of macrophages in vitro and atherosclerotic plaque inflammation in vivo in ApoE knockout mice. Thus, with the high accessibility of HA and ATV, HA-ATV NP is an excellent candidate for the treatment of inflammatory atherosclerotic plaques. Furthermore, our strategy can potentially be a platform technology, applicable to selective delivery of other statins48 or anti-inflammatory drugs49 to reduce plaque associated inflammation as many of these compounds can serve as the hydrophobic core of HA NPs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health (Grant R01GM072667) and Michigan State University for financial support of our work.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: The Supporting Information includes Figures S1–S20, and Scheme S1.

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Weber C and Noels H, Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options, Nat. Med, 2011, 17, 1410–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW and Turner MB, Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: A report from the American Heart Association, Circulation, 2016, 133, e38–e360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Wal AC, Becker AE, van der Loos CM and Das PK, Site of intimal rupture or erosion of thrombosed coronary atherosclerotic plaques is characterized by an inflammatory process irrespective of the dominant plaque morphology, Circulation, 1994, 89, 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oesterle A, Laufs U and Liao JK, Pleiotropic effects of statins on the cardiovascular system, Circ. Res, 2017, 120, 229–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwak B, Mulhaupt F, Myit S and Mach F, Statins as a newly recognized type of immunomodulator, Nat. Med, 2000, 6, 1399–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sparrow CP, Burton CA, Hernandez M, Mundt S, Hassing H, Patel S, Rosa R, Hermanowski-Vosatka A, Wang PR, Zhang D, Peterson L, Detmers PA, Chao YS and Wright SD, Simvastatin has anti-inflammatory and antiatherosclerotic activities independent of plasma cholesterol lowering, Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol, 2001, 21, 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armitage J, The safety of statins in clinical practice, Lancet, 2007, 370, 1781–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, Cheng Z, Ding L, Fang F, Cheng KA, Fang Q and Shi GP, Atorvastatin-induced acute elevation of hepatic enzymes and the absence of cross-toxicity of pravastatin, Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Therap, 2010, 48, 798–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laufs U, Scharnagl H, Halle M, Windler E, Endres M and März W, Treatment options for statin-associated muscle symptoms, Dtsch. Arztebl. Int, 2015, 112, 748–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lennernäs H, Clinical pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin, Clin. Pharmacokinet, 2003, 42, 1141–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duivenvoorden R, Tang J, Cormode DP, Mieszawska AJ, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Ozcan C, Otten MJ, Zaidi N, Lobatto ME, van Rijs SM, Priem B, Kuan EL, Martel C, Hewing B, Sager H, Nahrendorf M, Randolph GJ, Stroes ES, Fuster V, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA and Mulder WJ, A statin-loaded reconstituted high-density lipoprotein nanoparticle inhibits atherosclerotic plaque inflammation, Nat. Commun, 2014, 5, 3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hägg D, Sjöberg S, Hultén LM, Fagerberg B, Wiklund O, Rosengren A, Carlsson LMS, Borén J, Svensson P-A and Krettek A, Augmented levels of CD44 in macrophages from atherosclerotic subjects: a possible IL-6–CD44 feedback loop?, Atherosclerosis 2007, 190, 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuff CA, Kothapalli D, Azonobi I, Chun S, Zhang Y, Belkin R, Yeh C, Secreto A, Assoian RK, Rader DJ and Pure E, The adhesion receptor CD44 promotes atherosclerosis by mediating inflammatory cell recruitment and vascular cell activation, J. Clin. Invest, 2001, 108, 1031–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKee CM, Penno MB, Cowman M, Burdick MD, Strieter RM, Bao C and Noble PW, Hyaluronan (HA) Fragments Induce Chemokine Gene Expression in Alveolar Macrophages: the Role of HA Size and CD44, J. Clin. Invest, 1996, 98, 2403–2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain M, He Q, Lee W-S, Kashiki S, Foster LC, Tsai J-C, Lee M-E and Haber E, Role of CD44 in the reaction of vascular smooth muscle cells to arterial wall injury, J. Clin. Invest, 1996, 97, 596–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao L, Lee E, Zukas AM, Middleton MK, Kinder M, Acharya PS, Hall JA, Rader DJ and Puré E, CD44 expressed on both bone marrow–derived and non–bone marrow–derived cells promotes atherogenesis in ApoE-deficient mice, Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol, 2008, 28, 1283–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao L, Hall JA, Levenkova N, Lee E, Middleton MK, Zukas AM, Rader DJ, Rux JJ and Puré E, CD44 regulates vascular gene expression in a proatherogenic environment, Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol, 2007, 27, 886–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krettek A, Sukhova GK, Schönbeck U and Libby P, Enhanced expression of CD44 variants in human atheroma and abdominal aortic aneurysm. Possible role for a feedback loop in endothelial cells, Am. J. Pathol, 2004, 165, 1571–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolodgie FD, Burke AP, Farb A, Weber DK, Kutys R, Wight TN and Virmani R, Differential accumulation of proteoglycans and hyaluronan in culprit lesions. Insights into plaque erosion, Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol, 2002, 22, 1642–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krettek A, Sukhova GK, Schonbeck U and Libby P, Enhanced expression of CD44 variants in human atheroma and abdominal aortic aneurysm: possible role for a feedback loop in endothelial cells, Am J Pathol, 2004, 165, 1571–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hossaini Nasr S, Tonson A, El-Dakdouki MH, Zhu DC, Agnew D, Wiseman R, Qian C and Huang X, Effects of nanoprobe morphology on cellular binding and inflammatory responses: hyaluronan-conjugated magnetic nanoworms for magnetic resonance imaging of atherosclerotic plaques, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2018, 10, 11495–11507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beldman TJ, Senders ML, Alaarg A, Pérez-Medina C, Tang J, Zhao Y, Fay F, Deichmöller J, Born B, Desclos E, van der Wel NN, Hoebe RA, Kohen F, Kartvelishvily E, Neeman M, Reiner T, Calcagno C, Fayad ZA, de Winther MPJ, Lutgens E, Mulder WJM and Kluza E, Hyaluronan nanoparticles selectively target plaque-associated macrophages and improve plaque stability in atherosclerosis, ACS Nano, 2017, 11, 5785–5799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamat M, El-Boubbou K, Zhu DC, Lansdell T, Lu X, Li W and Huang X, Hyaluronic acid immobilized magnetic nanoparticles for active targeting and imaging of macrophages, Bioconjugate Chem, 2010, 21, 2128–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montanaro S, Lhiaubet-Vallet V, Iesce MI, Previtera L and Miranda MA, A mechanistic study on the phototoxicity of atorvastatin: singlet oxygen generation by a phenanthrene-like photoproduct, Chem. Res. Toxicol, 2009, 22, 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Dakdouki MH, Xia J, Zhu DC, Kavunga H, Grieshaber J, O’Reilly S, McCormick JJ and Huang X, Assessing the in vivo efficacy of doxorubicin loaded hyaluronan nanoparticles, ACS Appl. Mater, Inter, 2014, 6, 697–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Dakdouki MH, Pure E and Huang X, Development of drug loaded nanoparticles for tumor targeting. Part 2: Enhancement of tumor penetration through receptor mediated transcytosis in 3D tumor models, Nanoscale, 2013, 5, 3904–3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Dakdouki MH, Pure E and Huang X, Development of drug loaded nanoparticles for tumor targeting. Part 1: Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation in 2D cell cultures, Nanoscale, 2013, 5, 3895–3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bot PT, Pasterkamp G, Goumans MJ, Strijder C, Moll FL, de Vries JP, Pals ST, de Kleijn DP, Piek JJ and Hoefer IE, Hyaluronic acid metabolism is increased in unstable plaques, Eur. J. Clin. Invest, 2010, 40, 818–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park D, Cho Y, Goh SH and Choi Y, Hyaluronic acid-polypyrrole nanoparticles as pH-responsive theranostics, Chem. Commun, 2014, 50, 15014–15017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maiolino S, Moret F, Conte C, Fraix A, Tirino P, Ungaro F, Sortino S, Reddi E and Quaglia F, Hyaluronan-decorated polymer nanoparticles targeting the CD44 receptor for the combined photo/chemo-therapy of cancer, Nanoscale, 2015, 7, 5643–5653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gochman E, Mahajna J, Shenzer P, Dahan A, Blatt A, Elyakim R and Reznick AZ, The expression of iNOS and nitrotyrosine in colitis and colon cancer in humans, Acta Histochem, 2012, 114, 827–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Detmers PA, Hernandez M, Mudgett J, Hassing H, Burton C, Mundt S, Chun S, Fletcher D, Card DJ, Lisnock J, Weikel R, Bergstrom JD, Shevell DE, Hermanowski-Vosatka A, Sparrow CP, Chao YS, Rader DJ, Wright SD and Pure E, Deficiency in inducible nitric oxide synthase results in reduced atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice, J. Immunol, 2000, 165, 3430–3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang H, Koelle P, Fendler M, Schrottle A, Czihal M, Hoffmann U, Conrad M and Kuhlencordt PJ, Induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression by oxLDL inhibits macrophage derived foam cell migration, Atherosclerosis, 2014, 235, 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao JF, Shyue SK, Lin SJ, Wei J and Lee TS, Excess nitric oxide impairs LXR(alpha)-ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux in macrophage foam cells, J. Cell. Physiol, 2014, 229, 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meir KS and Leitersdorf E, Atherosclerosis in the apolipoprotein-E-deficient mouse: a decade of progress, Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol, 2004, 24, 1006–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang X, Yang LX, Guo R, Shi Y, Hou X, Yang Z, Zhou X and Liu H, Atorvastatin attenuates plaque vulnerability by downregulation of EMMPRIN expression via COX-2/PGE2 pathway, Exp. Ther. Med, 2017, 13, 835–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan X, Hou R, Ma A, Wang T, Wu M, Zhu X, Yang S and Xiao X, Atorvastatin upregulates the expression of miR-126 in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice with carotid atherosclerotic plaque, Cell. Mol. Neurobiol, 2017, 37, 29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rayahin JE, Buhrman JS, Zhang Y, Koh TJ and Gemeinhart RA, High and low molecular weight hyaluronic acid differentially influence macrophage activation, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng, 2015, 1, 481–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krolikoski M, Monslow J and Pure E, The CD44-HA axis and inflammation in atherosclerosis: A temporal perspective, Matrix Biol, 2019, 78–79, 201–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maiti A, Maki G and Johnson P, TNF-alpha induction of CD44-mediated leukocyte adhesion by sulfation, Science, 1998, 282, 941–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kircher MF, Grimm J, Swirski FK, Libby P, Gerszten RE, Allport JR and Weissleder R, Noninvasive in vivo imaging of monocyte trafficking to atherosclerotic lesions, Circulation, 2008, 117, 388–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakhlband A, Eskandani M, Omidi Y, Saeedi N, Ghaffari S, Barar J and Garjani A, Combating atherosclerosis with targeted nanomedicines: recent advances and future prospective, Bioimpacts, 2018, 8, 59–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tarin C, Carril M, Martin-Ventura JL, Markuerkiaga I, Padro D, Llamas-Granda P, Moreno JA, Garcia I, Genicio N, Plaza-Garcia S, Blanco-Colio LM, Penades S and Egido J, Targeted gold-coated iron oxide nanoparticles for CD163 detection in atherosclerosis by MRI, Sci. Rep, 2015, 5, 17135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Röhrl C and Stangl H, HDL endocytosis and resecretion, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 2013, 1831, 1626–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuai R, Li D, Chen YE, Moon JJ and Schwendeman A, High-Density Lipoproteins (HDL) – nature’s multi-functional nanoparticles, ACS Nano, 2016, 10, 3015–3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flores AM, Hosseini-Nassab N, Jarr KU, Ye J, Zhu X, Wirka R, Koh AL, Tsantilas P, Wang Y, Nanda V, Kojima Y, Zeng Y, Lotfi M, Sinclair R, Weissman IL, Ingelsson E, Smith BR and Leeper NJ, Pro-efferocytic nanoparticles are specifically taken up by lesional macrophages and prevent atherosclerosis, Nat. Nanotechnol, 2020, 15, 154–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mansukhani NA, Peters EB, So MM, Albaghdadi MS, Wang Z, Karver MR, Clemons TD, Laux JP, Tsihlis ND, Stupp SI and Kibbe MR, Peptide amphiphile supramolecular nanostructures as a targeted therapy for atherosclerosis, Macromol. Biosci, 2019, 19, e1900066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ratchford EV, Gutierrez J, Lorenzo D, McClendon MS, Della-Morte D, DeRosa JT, Elkind MSV, Sacco RL and Rundek T, Short-term effect of atorvastatin on carotid artery elasticity: a pilot study, Stroke, 2011, 42, 3460–3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lameijer M, Binderup T, van Leent MMT, Senders ML, Fay F, Malkus J, Sanchez-Gaytan BL, Teunissen AJP, Karakatsanis N, Robson P, Zhou X, Ye Y, Wojtkiewicz G, Tang J, Seijkens TTP, Kroon J, Stroes ESG, Kjaer A, Ochando J, Reiner T, Pérez-Medina C, Calcagno C, Fisher EA, Zhang B, Temel RE, Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M, Fayad ZA, Lutgens E, Mulder WJM and Duivenvoorden R, Efficacy and safety assessment of a TRAF6-targeted nanoimmunotherapy in atherosclerotic mice and non-human primates, Nat. Biomed. Eng, 2018, 2, 279–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.