Abstract

COVID-19, a new viral disease affecting primarily the respiratory system and the lung, has caused a pandemic posing serious challenges to healthcare systems around the world. In about 20% of patients, severe symptoms occur after a mean incubation period of 5 – 6 days; 5% of patients need intensive care therapy. Mortality is about 1 – 2%. Protecting healthcare workers is of paramount importance in order to prevent hospital-acquired infections. Therefore, during all procedures associated with aerosol production, personal protective equipment consisting of a FFP2/FFP3 (N95) respiratory mask, gloves, safety glasses and a waterproof overall should be used. Therapy is based on established recommendations issued for patients with acute lung injury (ARDS). Lung protective ventilation, prone position, restrictive fluid management and adequate management of organ failure are the mainstays of therapy. In case of fulminant lung failure, veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may be used as a rescue in experienced centres. New, experimental therapies are evolving with ever increasing frequency; currently, however, no evidence-based recommendation is possible. If off-label and compassionate use of these drugs is considered, an individual benefit-risk assessment is necessary, since serious side effects have been reported.

Key words: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, critical care, adult respiratory distress syndrome, acute lung injury, personal protection equipment, N95 respiratory masks

Abbreviations

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- COVID-19

corona virus disease 2019

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- ECMO

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- EI

endotracheal intubation

- FFP2/FFP3

filtering face piece (protection classes 2/3)

- IL

interleukin

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- NIV

non-invasive ventilation

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- PPE

personal protective equipment

- RKI

Robert Koch Institute

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2

- SSC

Surviving Sepsis Campaign

- TNF

tumour necrosis factor

Introduction

The new coronavirus, known as SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2), has caused a global pandemic within a short period of time. The clinical presentation, i.e., the disease itself, has been given the name COVID-19 (corona virus disease 2019). Since the initial period of transmission of infections, the number of infections reported in the Peopleʼs Republic of China and in numerous European countries has risen exponentially 1 and significantly exceeded the capacity of healthcare systems in certain countries such as Italy. Physicians and nursing staff are therefore in urgent need of information about efficient ways of diagnosing the disease and evidence-based treatment.

Epidemiology

It is currently assumed that SARS-CoV-2 was present in an animal reservoir (the market for seafood and reptiles in Wuhan, Peopleʼs Republic of China) from where it passed to human hosts at the beginning of December 2019 2 . The original reservoir species is still unknown, but bats are considered the most likely source 3 . With Wuhan as the starting point, the virus spread across all of mainland China, with a significant concentration of cases occurring in the province of Hubei 4 .

Initially, the number of infections in all affected countries increased exponentially, although the curve has since flattened following drastic measures taken by some countries to avoid social contacts (Peopleʼs Republic of China, Taiwan, Singapore) 5 . The characteristic exponential infection curve is due to SARS-CoV-2 being highly contagious. Based on a meta-analysis of 12 studies published until 7 February 2020, the mean basic reproduction number for SARS-CoV-2 is currently 3.28 infections per infected individual, a considerably higher number than that of SARS.

Data from China suggested, that every infected individual infects an average of 3.28 other people 6 .

According to current calculations, the case fatality rate (= the number of infected persons who die of the infection; lethality) of SARS-CoV-2 is just 1.4%, although the risk of developing symptomatic infection increases with age (approx. 4% per year for adults between the ages of 30 – 60 years) 7 . Patients over the age of 59 years have a 5-fold higher risk of dying from COVID-19. Children are often not affected or only to a minor extent, but they can pass on the infection. It is currently not expected that large numbers of children will be seriously affected 8 .

The average incubation period is about 5 – 6 days (range: 0 – 14 days). However, the virus is still detectable in infected persons up to 30 days from onset of illness, which makes it more difficult to classify asymptomatic patients as cured even if they appear to have recovered from the infection 9 .

There is currently insufficient evidence to be able to say whether persons who had the disease develop immunity and how long this immunity persists 10 . Data from animal studies suggest that, as with other viral diseases, infected individuals do develop immunity which subsequently prevents clinically apparent reinfection 11 .

Clinical Characteristics

COVID-19 is primarily an infection of the upper and lower respiratory tract. The efficient proliferation of the virus within the nasopharyngeal cavity is considered one of the reasons for the high contagiousness of the virus 12 . Otherwise, the clinical characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 resemble those of other viral diseases which affect the lungs: fever, cough, fatigue.

According to data from the Peopleʼs Republic of China, more than 80% of affected patients are asymptomatic or present with only mild symptoms, around 15% develop more serious general symptoms including pneumonia, and around 5% of patients become critically ill and develop sepsis, septic shock or multi-organ failure 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ( Table 1 ). The lethality is between 1 – 2%. Men are affected significantly more often than women 16 , 23 . The figures may vary, depending on the intensity and time of testing. This appears to be the case in Italy.

Table 1 Classification of symptoms and severity in persons with COVID-19 (data from 18 ).

| Severity | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Mild (outpatient/ normal ward) | Fever Cough Fatigue |

| Severe (IMC = intermediate care) | Dyspnoea Respiratory rate ≥ 30/min SaO 2 ≤ 93% paO 2 /FiO 2 < 300 Lung infiltrates > 50% within 24 – 48 h |

| Critically ill (ICU = intensive care unit) | Lung failure Septic shock Multi-organ failure |

Critically ill patients present with the classic features of ARDS including hyaline membrane formation, consolidated areas in the lungs and atelectasis 19 . Images of the thorax obtained with computed tomography show ground-glass opacity in more than 50% of cases and bilateral shadows 16 ; bilateral shadowing was also found in > 50% of cases with conventional X-ray imaging 20 .

On admission to hospital, more than 80% of patients were found to have lymphocytopenia; laboratory tests in a cohort of 173 patients from Wuhan with severe disease showed elevated CRP (≥ 10 mg/l, 81.5%), LDH (≥ 250 U/l, 58.1%) and D-dimer (≥ 0.5 mg/l, 59.8%) levels in a majority of patients, while only 13.7% of patients had elevated procalcitonin levels of more than ≥ 0.5 ng/l 16 . Elevated D-dimer and serum ferritin levels have also been reported in other cohorts 21 , 22 .

In general, it appears that older men with comorbidities are more likely to fall ill and more likely to die.

Around half of patients with COVID-19 have chronic comorbidities; the majority have cardiovascular or cerebrovascular comorbidities or diabetes mellitus 23 . Some patients with severe course of disease had coinfections with bacteria and fungi. Examination of cultures has identified Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Aspergillus flavus, Candida glabrata and Candida albicans among others 23 .

Diagnosis

In cases suspicious for infection with SARS-CoV-2, the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) recommends obtaining parallel samples from the upper and lower respiratory tract, depending on the clinical situation. It is important to use swabs suitable for detecting the virus (virus swabs with an appropriate transport medium or, if necessary, dry swabs moistened with a small amount of NaCl solution; no agar swabs).

The material should be examined with RT-PCR for the presence of viral RNA 24 . If the material needs to be preserved for longer periods, it must be stored at a temperature of 4 °C.

According to the recommendations of the RKI ( www.rki.de/covid-19-falldefinition ; as per: 28.03.2020), testing should focus on symptomatic persons and individuals suspected of having the virus based on a differential diagnosis.

A clinical suspicion of infection is based on an individualʼs previous history, symptoms or findings consistent with COVID-19 disease, and whether a diagnosis for a different disease exists which could adequately explain the presenting symptoms and clinical picture 25 .

In practice, the recurrent issue for medical staff is which contacts should lead to testing.

A category 1 contact person is defined a person who had face-to-face contact for a cumulative period of at least 15 minutes with a known COVID-19 patient, e.g. during a conversation 25 . Persons who had this type of contact should initially be sent home to self-isolate (quarantine) for 14 days. For medical staff, this category has been subdivided further into category 1a and 1b contact persons.

A category 1a contact is a person with high-risk exposure, e.g. someone who had unprotected exposure to secretions and aerosols from COVID-19 patients (intubation and extubation of the patient, bronchoscopy, aspiration, nebulisation, manual ventilation prior to endotracheal anaesthesia, proning the patient, noninvasive ventilation (NIV), tracheotomy and cardiopulmonary resuscitation) 26 . This group of people should usually be required to quarantine themselves at home for a period of 14 days. As medical staff are a very limited resource, in view of the shortage of relevant staff, the RKI has recommended a shorter isolation period of 7 days for this group.

Persons classified as contact category 1b had contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case in the context of delivering care or undertaking a medical examination (> 15 min, ≤ 2 m distance) without personal protective equipment but also without carrying out a high-risk procedure. Because of the shortage of staff, this group of persons may continue working but should use a surgical mask to cover their mouth and nose for a period of 14 days.

No special precautions are required for category 3 contact persons; this category covers medical staff who were in the same room as a confirmed COVID-19 case and were not wearing adequate personal protective equipment but were never closer than 2 metres, did not come into direct contact with secretions or excretions of the patient and were not exposed to aerosols as well as medical staff who were closer than 2 m to the patient but were wearing adequate personal protective equipment throughout the entire contact period 26 .

The overview below summarises the contact categories and appropriate response for each category.

Hygiene Measures

Cave.

Data from Wuhan and Italy show that around 4 – 20% of medical staff were infected with the virus while caring for COVID-19 patients 18 , 27 .

In addition to strict observance of the rules of basic hygiene, it is critically important to ensure that staff are adequately provided with personal protective equipment. Because the disease is highly contagious, use of a FFP2/FFP3 (face filtering piece) respirator mask is recommended for all aerosol-generating procedures performed when caring for patients. Staff must additionally wear protective goggles and a waterproof apron or gown 28 .

Class 2 and 3 FFP masks are characterised by a very low levels of overall leakage, which is why they offer good protection against aerosols (droplet infection); however, working while wearing FFP2/FFP3 respirator masks is only possible for limited periods of time because of the high breathing resistance 29 .

As it is expected that supplies of FFP2/FFP3 respirator masks will be insufficient during the pandemic, it is necessary to also think about alternative approaches in an emergency. In its recently published recommendations on the treatment of patients with COVID-19, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) cited a current meta-analysis which did not find special respiratory masks (analogous to our FFP2/FFP3 masks) to be superior to conventional surgical masks with regard to preventing the infection from spreading to healthcare staff who treated infectious patients 30 . A randomised study on the treatment of patients which included a number of patients infected with the coronavirus also reported that surgical masks were noninferior to N95 respirator masks 31 . This means that, in exceptional situations, providing patients and healthcare staff with surgical masks could be a useful means of reducing the risk of infection for medical staff, at least when treating spontaneously breathing patients.

However, during all aerosol-generating procedures, it is absolutely essential that medical staff wear a FFP2 mask at the very least, or better still a FFP3 mask (see above) for their own protection. The German Society for Pneumology and Respiratory Medicine recently published detailed recommendations 32 . To reduce the use of FFP2/FFP3 masks, it is recommended that medical staff wear personal protective equipment (PPE) during as many of their encounters with patients as possible. When treating patients with the virus who are on the same ward, several patients can be treated while wearing the same PPE. Between contacts with patients, the FFP mask can be placed between 2 low-microbe disposable cardboard kidney dishes if it is possible to prevent the inside of the mask from being contaminated.

To ensure that sufficient PPE is available for all medical staff despite the increased demand during the pandemic, tests are currently being carried out to see whether it would be possible to re-use used FFPS masks using suitable reprocessing methods. Before the reprocessed masks are released for use, it will be necessary to test whether the masks continue to fulfil their protective function after reprocessing.

Treatment

Around 20% of patients develop severe symptoms ( Table 1 ), and around 5% require treatment in an intensive care unit. The lungs react to the disease-causing agent SARS-CoV-2 in the same way they react to other viruses which attack the respiratory system. Patients present with pathophysiological changes which are known to also occur in patients with influenza or viral SARS pneumonia. This means, specifically, that the treatment of patients with COVID-19 must be based, first and foremost, on best standard care, i.e., on optimal compliance with evidence-based treatment recommendations developed to treat acute lung failure (acute respiratory distress syndrome, ARDS) 33 .

The recommendations of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) published very recently in the context of the current corona pandemic include a total of 50 statements which were assigned different levels of recommendation 34 .

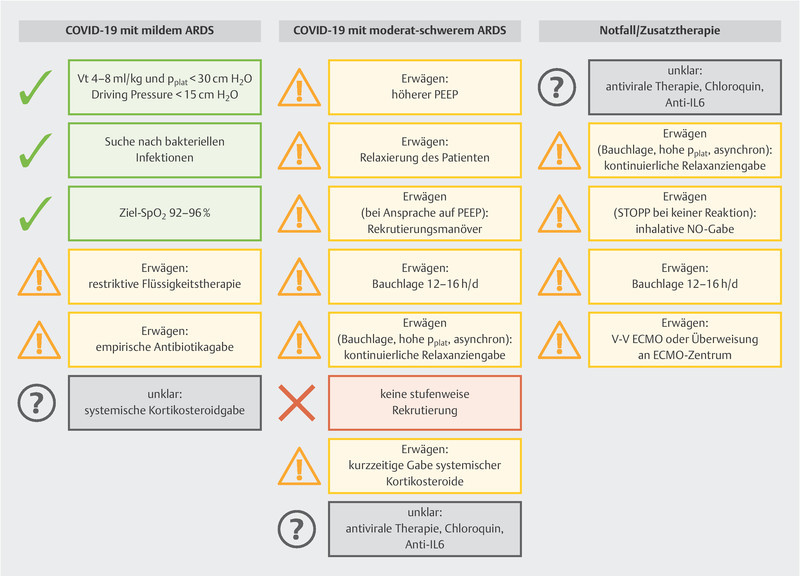

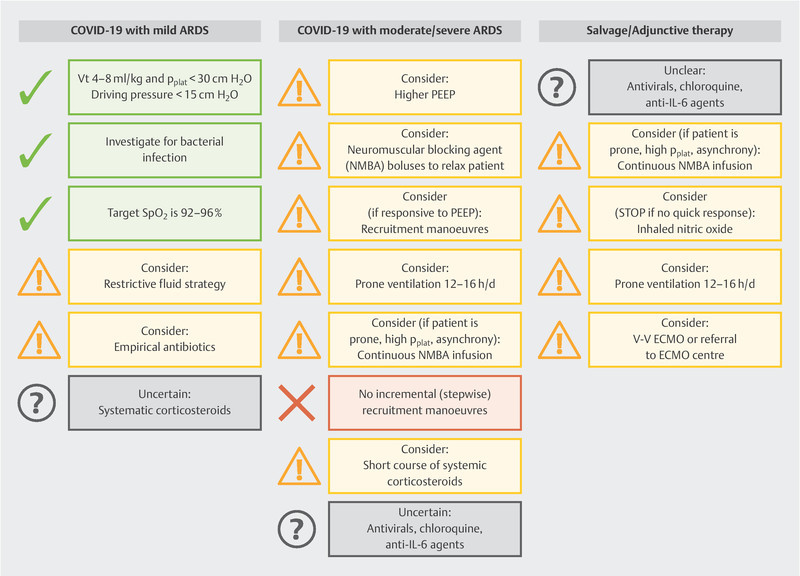

The measures listed below are the only ones given a strong recommendation (cf. also Fig. 1 ):

Fig. 1.

Summary of clinical recommendations to treat COVID-19 patients [data from: Alhazzani W, Moller MH, Arabi YM et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Guidelines on the Management of Critically Ill Adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (in press). doi:10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5 ].

Recommendation against the use of dopamine,

Recommendation for lung-protective ventilation: low tidal volume ventilation (V t ) of 4 – 8 ml/kg predicted body weight, PEEP > 10 cm H 2 O, but no incremental (stepwise) PEEP recruitment,

Recommendation for supplemental oxygen if SpO 2 is < 90% (but SpO 2 must not be > 96%).

Additional measures (e.g., proning, restrictive administration of fluids and veno-venous ECMO as emergency therapy) may be considered.

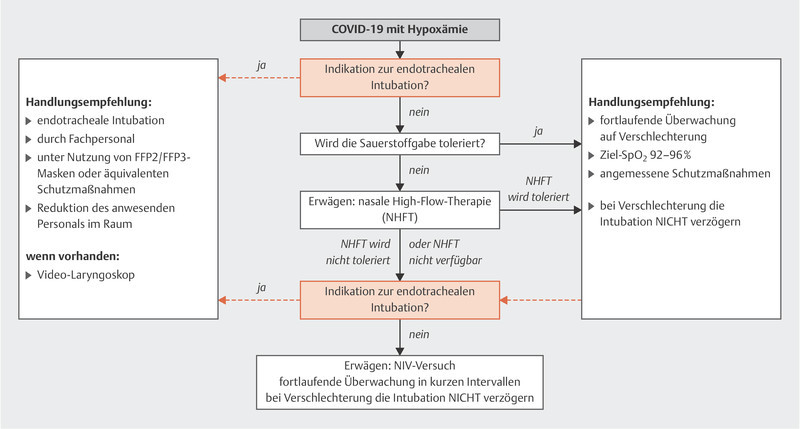

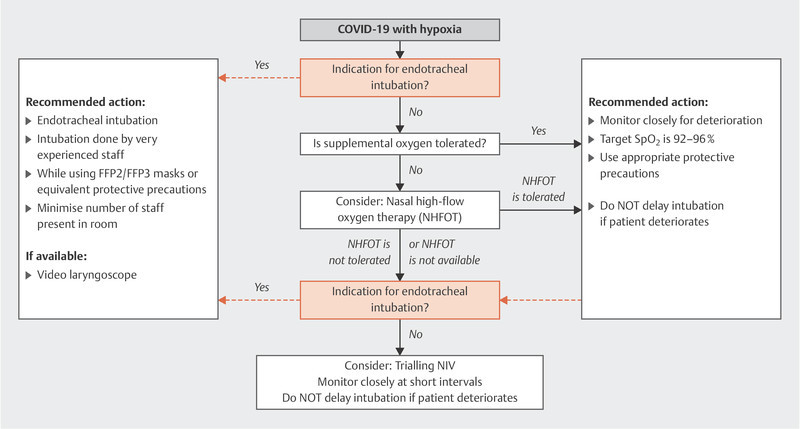

Fig. 2 shows the suggested approach for hypoxemia. Non-invasive ventilation is usually an important component of treatment for acute lung failure. However, the use of non-invasive ventilation and high-flow nasal oxygen therapy are associated with aerosol generation.

Fig. 2.

Treatment algorithm for patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory insufficiency caused by COVID-19 [data from: Alhazzani W, Moller MH, Arabi YM et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Guidelines on the Management of Critically Ill Adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (in press). doi:10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5 ].

If these forms of treatment are used, it is important to ensure the nasal high-flow cannula or NIV mask have an optimal fit. An NIV helmet is preferable if the patient can tolerate it.

Because of the above-mentioned problem of aerosol generation, ventilation based on endotracheal intubation is the preferred approach for patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory insufficiency 35 .

Transpulmonary thermodilution (PiCCO2, Pulsion-Maquet or EV1000, Edwards Life Sciences) can be used to guide the restrictive fluid strategy as it can be used to measure extravascular lung water, which plays an important prognostic role in acute lung failure 36 , 37 .

Paracetamol or metamizole can be used to reduce fever. Although the WHO has withdrawn its warning, the data on ibuprofen is still unclear, with NSAID use associated with an increased risk of bleeding 38 .

Experimental procedures

Outside best standard care, there is also a huge interest in new and experimental treatment procedures, although there are currently no data available for the overwhelming majority of new procedures. A very recently published study on the use of a combination of lopinavir and ritonavir was unable to show any survival benefits for COVID-19 patients 39 .

Remdesivir (pharmaceutical company: Gilead Sciences, Inc.) is another effective antiviral agent which was originally developed to treat infections associated with the Ebola virus. Remdesivir is effective to treat a wide range of different viruses, including filoviruses, paramyxoviruses, pneumo-viruses and pathogenic coronaviruses 40 . In cell cultures inoculated with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronaviruses, remdesivir was found to be superior to a combination of lopinavir/ritonavir 30 . The first data from Chinese patients are expected in early April. However, the substance is currently not available in Germany outside of controlled trials.

Early on, the suggestion was made that chloroquine could be a potentially effective antiviral drug; however, positive results in cell cultures and animal experiments could not be replicated or confirmed in clinical practice 41 . A recent Letter to the Editor 42 reported positive effects in 100 patients in a Chinese multicentre study. In the group which received the drug, it was found to prevent exacerbation of pneumonia, improve X-ray findings and shorten the overall course of disease. No relevant side effects were noted. There are currently no peer-reviewed publications on its use in this context; a recent systematic review into the use of chloroquine to treat COVID-19 disease recommended that chloroquine should only be administered in accordance with the Monitored Emergency Use of Unregistered Interventions (MEURI) protocol 43 .

Based on the available evidence, it is currently not possible to recommend any of these therapies. In each case, an individual risk-benefit assessment is necessary prior to initiating the off-label use of particular substances, as serious side effects have been reported 44 .

There is also considerable interest in the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) as an emergency therapy 45 . Veno-venous ECMO (vv-ECMO) is already an established procedure to treat refractory respiratory failure and appears to be associated with a survival benefit in a subgroup of patients 46 , 47 . There is general agreement that this therapy should only be carried out in experienced centres. As with other medical procedures, a minimum of 20 veno-venous ECMO runs per year is considered the minimum entry criterion 20 .

A small subgroup of COVID-19 patients experience a cytokine storm during infection, which is caused by an overwhelming and excessive release of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-2, IL-7, interferon-γ, TNF-α) 22 . Serum ferritin and IL-6 levels were found to be significantly elevated in samples obtained from deceased individuals from this subgroup of patients 48 . This is the rationale behind specific anti-inflammatory treatments, for example, the administration of interferon β-1b, the IL-1 blocker anakinra, the IL-6 receptor blocker tocilizumab or corticosteroids. There are no evidence-based data for any of the therapies mentioned here; analogously to the recommendations on the treatment of septic shock, corticosteroids may be considered as a hydrocortisone therapy (200 mg/24 h) in patients with high vasopressor doses.

Improved outcomes were reported in a case series of patients with septic shock and high cytokine concentrations (e.g. an IL-6 of ≥ 1000 pg/ml) following the use of a cytokine filter (Cytosorbents, Berlin, Germany) 49 . This requires an extracorporeal circulation (hemofiltration and/or ECMO) in which the filter can be incorporated. Cytokine removal could be an interesting treatment option for patients who meet the criteria. Antibiotic dosages may need to be adjusted accordingly.

Core Statements.

COVID-19 is a new viral disease that affects the respiratory system. The currently available data suggest that around 20% of cases develop severe symptoms, and around 5% of all cases require intensive care. Mortality is between 1 and 2% of all persons who develop the disease.

Adequate protection of medical staff is essential to prevent nosocomial infection. Medical staff must therefore wear personal protective equipment consisting of an FFP2/FFP3 mask, safety goggles and a waterproof overall during all aerosol-generating procedures.

Intensive care treatment of patients with lung failure is based on established recommendations for the treatment of patients with ARDS issued by the relevant professional societies. The focus is on lung-protective ventilation, prone positioning, restrictive fluid management and adequate management of other organ insufficiencies. Patients requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation must be treated in centres experienced in providing this type of organ support.

New and experimental treatment options are being discussed. However, based on the currently available evidence, it is not yet possible to recommend any of these approaches. In every case, an individual risk-benefit assessment is necessary prior to initiating the off-label use of particular substances as serious side effects have been reported.

Information.

This is a translation of “SARS CoV-2/COVID-19: Evidence-Based Recommendations on Diagnosis and Therapy” published in: Anästhesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther 2020; 55: 257 – 265

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Hauke Sieg, Klinik für Anästhesiologie, Intensivmedizin, Notfallmedizin und Schmerztherapie Asklepios Klinik St. Georg, Hamburg, for producing the illustrations. We would like to thank PD Dr. Wiest, Klinik für Pneumologie, Asklepios Klinikum Harburg, and Dr. Hohl-Radke, Klinik für Psychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie, Asklepios Fachkliniken Brandenburg, for their valuable remarks and comments.

Danksagung

Die Autoren danken Herrn Hauke Sieg, Klinik für Anästhesiologie, Intensivmedizin, Notfallmedizin und Schmerztherapie Asklepios Klinik St. Georg, Hamburg für das Anfertigen der Abbildungen. Herrn PD Dr. Wiest, Klinik für Pneumologie, Asklepios Klinikum Harburg, und Herrn Dr. Hohl-Radke, Klinik für Psychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie, Asklepios Fachkliniken Brandenburg, danken wir für wertvolle Hinweise und Kommentare.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt Prof. Bein received honoraria for consulting and giving lectures from Pulsion/Maquet, Edwards Life Sciences and Cytosorbents. The other authors state that they have no conflict of interest./ Prof. Bein hat Honorare für Vorträge und Beratertätigkeit von Pulsion/Maquet, Edwards Life Sciences und Cytosorbents erhalten. Die anderen Autorinnen/Autoren geben an, dass keine Interessenkonflikte bestehen.

Overview. The 3 contact categories for medical staff.

There are 3 different contact categories for medical staff.

Category Ia

Risky contact with aerosol production.

→ If there are staff shortages: 7 days self-isolation at home followed by testing.

Category Ib

Risky contact without aerosol exposure, distance to patient was < 2 metres, duration of contact was > 15 minutes.

→ If there are staff shortages: can return directly to work with patients if wearing a surgical mask covering mouth and nose.

Category III

No aerosol contact, distance to patient was > 2 metres, duration of contact was < 15 minutes or aerosol + adequate personal protective equipment.

→ No particular measures required.

References/Literatur

- 1.Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins UniversityOnline:https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.htmllast access: 28.03.2020

- 2.Rothan H A, Byrareddy S N. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen K G, Rambaut A, Lipkin W I. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adhikari S P, Meng S, Wu Y-J. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:29. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang C J, Ng C Y, Brook R H. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng Z J, Shan J. 2019 Novel coronavirus: where we are and what we know. Infection. 2020;48:155–163. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01401-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu J T, Leung K, Bushman M. Estimating clinical severity of COVID-19 from the transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China. Nat Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0822-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruz A, Zeichner S. COVID-19 in children: initial characterization of the pediatric disease. Pediatrics. 2020 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Z, McGoogan J M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Center of Disease Control Healthcare Professionals: frequently asked questions and answers. CDCOnline:https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/faq.htmllast access: 28.03.2020

- 11.Bao L, Deng W, Gao H. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 2020. Reinfection could not occur in SARS-CoV-2 infected rhesus macaques. bioRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M. SARS-CoV-2 Viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Z, McGoogan J. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan E, Brodie D, Slutsky A S. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA. 2018;319:698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.AWMF S3-Leitlinie Invasive Beatmung und Einsatz extrakorporaler Verfahren bei akuter respiratorischer Insuffizienz, 1. Aufl., Langversion. Stand 04.12.2017Online:https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/001-021l_S3_Invasive_Beatmung_2017-12.pdflast access: 28.03.2020

- 21.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta P, McAuley D F, Brown M. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reusken C BEM, Broberg E K, Haagmans B. Laboratory readiness and response for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in expert laboratories in 30 EU/EEA countries, January 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.6.2000082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robert Koch-Institut – RKI Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 – Hinweise zur Testung von Patienten auf Infektion mit dem neuartigen Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2Online:https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Vorl_Testung_nCoV.htmllast access: 28.03.2020

- 26.Robert Koch-Institut – RKI Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 – Optionen zum Management von Kontaktpersonen unter medizinischem Personal bei PersonalmangelOnline:https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/HCW.htmllast access: 28.03.2020

- 27.COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30066-7. Lancet. 2020;395:922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.AWMF online Empfehlungen Krankenhaushygiene: Hygieneanforderungen respiratorisch übertragbare Infektions-ErkrankungenOnline:https://www.awmf.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Leitlinien/029_AWMF-AK_Krankenhaus-_und_Praxishygiene/HTML-Dateien/029-032l_S1_Hygiene_respiratorisch-uebertragbare_Infektionserkrankungen_2016-01.htmllast access: 28.03.2020

- 29.Robert Koch-Institut – RKI . Infektionsprävention im Rahmen der Pflege und Behandlung von Patienten mit übertragbaren Krankheiten. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58:1151–1170. doi: 10.1007/s00103-015-2234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez M A. Compounds with therapeutic potential against novel respiratory 2019 coronavirus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00399-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radonovich L J, Simberkoff M S, Bessesen M T. N95 Respirators vs. Medical Masks for Preventing Influenza Among Health Care Personnel. JAMA. 2019;322:824. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sektion 2 Endoskopie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin EmpfehlungOnline:https://pneumologie.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Aktuelles/2020-03_DGP-Empfehlung_Broncho_Covid19.pdflast access: 04.04.2020

- 33.Fan E, Brodie D, Slutsky A S. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. JAMA. 2018;319:698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oczkowski S, Levy M M, Derde L. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Guidelines on the Management of Critically Ill Adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Authors Intensive Care Medicine (ICM) and Critical Care Medicine (CCM) Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kluge S, Janssens U, Welte T. Empfehlungen zur intensivmedizinischen Therapie von Patienten mit COVID-19. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfallmed. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00063-020-00674-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LeTourneau J L, Pinney J, Phillips C R. Extravascular lung water predicts progression to acute lung injury in patients with increased risk. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:847–854. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236f60e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bein B, Renner J. Best practice & research clinical anaesthesiology: Advances in haemodynamic monitoring for the perioperative patient. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2019;33:139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Müller C.DAZ online. WHO rät doch nicht von Ibuprofen ab: Ibuprofen und COVID-19: WHO rudert zurückOnline:https://www.deutsche-apotheker-zeitung.de/news/artikel/2020/03/19/ibuprofen-und-covid-19-who-rudert-zuruecklast access: 28.03.2020

- 39.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D. A Trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang L, Liu Y. Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: A systematic review. J Med Virol. 2020;92:479–490. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Touret F, de Lamballerie X. Of chloroquine and COVID-19. Antiviral Res. 2020;177:104762. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X. Breakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci Trends. 2020;14:72–73. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cortegiani A, Ingoglia G, Ippolito M. A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. J Crit Care. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalil A C. Treating COVID-19 – Off-label drug use, compassionate use, and randomized clinical trials during pandemics. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramanathan K, Antognini D, Combes A. Planning and provision of ECMO services for severe ARDS during the COVID-19 pandemic and other outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peek G J, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1351–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965–1975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kogelmann K, Jarczak D, Scheller M. Hemoadsorption by CytoSorb in septic patients: a case series. Crit Care. 2017;21:74. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1662-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]