Abstract

Background:

Long-term colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence and mortality after colorectal polyp removal remains unclear. We aimed to assess CRC incidence and mortality in individuals with removal of different histological subtypes of polyps relative to the general population.

Methods:

We performed a matched cohort study through prospective record linkage in Sweden among 178,377 patients with a colorectal polyp in the nationwide gastrointestinal ESPRESSO histopathology cohort (1993-2016), and 864,831 matched reference individuals from the general population. Polyps were classified by morphology codes into hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenoma/polyps (SSA/Ps), tubular adenomas, tubulovillous adenomas, and villous adenomas.

Findings:

The mean age of patients at polyp diagnosis was 58.6 years for hyperplastic polyps, 59.7 for SSA/Ps, 63.9 for tubular adenomas, 67.1 for tubulovillous adenomas, and 68.9 for villous adenomas. We documented 4,278 incident CRCs and 1,269 CRC-related deaths among patients with a polyp. Compared to reference individuals, patients with any polyps had an increased risk of CRC, with multivariable hazard ratio (HR) (95% CI) of 1.11 (1.02-1.22) for hyperplastic polyps, 1.41 (1.30-1.52) for tubular adenomas, 1.77 (1.34-2.34) for SSA/Ps, 2.56 (2.36-2.78) for tubulovillous adenomas, to 3.82 (3.07-4.76) for villous adenomas. The 10-year cumulative incidence of CRC (95% CI) for these polyp subgroups was 1.6% (1.5-1.7%), 2.7% (2.5-2.9%), 2.5% (1.9-3.3%), 5.1% (4.8-5.4%), and 8.6% (7.4-10.1%), respectively, compared with 2.1% (2.0-2.1%) among reference individuals. A higher proportion of incident proximal colon cancer was found among patients with hyperplastic polyps (501 [57%] of 878) and SSA/Ps (40 [52%] of 77) than adenomas (30-46%). For CRC mortality, a positive association was found for SSA/Ps (HR, 1.74, 95% CI, 1.08-2.79), tubulovillous adenomas (1.95, 1.69-2.24), and villous adenomas (3.45, 2.40-4.95), but not hyperplastic polyps or tubular adenomas.

Interpretation:

In a largely screening-naïve population, compared to general individuals, patients with any polyps had a higher CRC incidence, and those with SSA/Ps, tubulovillous adenomas, and villous adenomas had a higher CRC mortality.

Funding:

This study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, American Cancer Society, American Gastroenterological Association, and Union for International Cancer Control.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in the world.1 Endoscopic screening reduces CRC incidence and mortality by detection and removal of precursor lesions. While the conventional adenoma-to-carcinoma sequence has been well described and accounts for a majority of CRC cases, there is an alternative pathway for another 20-30% of CRC cases in which sessile serrated adenoma/polyps (SSA/Ps) represent the major precursor lesions.2 Of note, because of their predilection for the proximal colon and their subtle and flat endoscopic appearance, SSA/Ps are easily missed or incompletely removed endoscopically, resulting in their disproportionate contribution to “interval CRC” diagnosed among patients still within recommended surveillance periods after polypectomy.3,4

To prevent subsequent cancer, individuals diagnosed with either conventional adenomas or SSA/Ps by screening endoscopy are advised to undergo colonoscopy surveillance at different intervals, depending on the most advanced findings of the index endoscopy. However, existing guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance vary widely and lack sufficient evidence.5–10 Most supporting data are based on the risk of recurrence of advanced neoplasia following polypectomy,11 and only a few prospective studies have examined CRC as the endpoint among individuals with conventional adenomas or SSA/Ps.12–20 For SSA/Ps, most studies have very limited number of CRC cases (n<30),13,15 except for a recent large prospective case-control study in Denmark that observed higher incidence of CRC among individuals with SSA/Ps than those with no polyp.16

Recently, we assessed CRC incidence after diagnosis of conventional adenomas and serrated polyps in three population-based cohorts and found an increased risk associated with advanced adenoma and large serrated polyps.13 However, in that study, we were unable to distinguish between hyperplastic polyps and SSA/Ps and to assess CRC mortality. Therefore, comprehensive assessment of both CRC incidence and mortality after diagnosis of various polyp subtypes is lacking. Such information is important to better understand the influence of different pathways on CRC and help improve the current colonoscopy surveillance guidelines for better prevention of CRC.

In this study, using the prospectively collected data from national registries in Sweden, we assessed CRC incidence and mortality among individuals diagnosed with different subtypes of colorectal polyps and their matched reference individuals identified from the general population. We hypothesized that patients with a polyp had a higher CRC incidence and mortality than the reference individuals and that the risk increase was greater for more advanced polyps.

Materials and methods

Study population

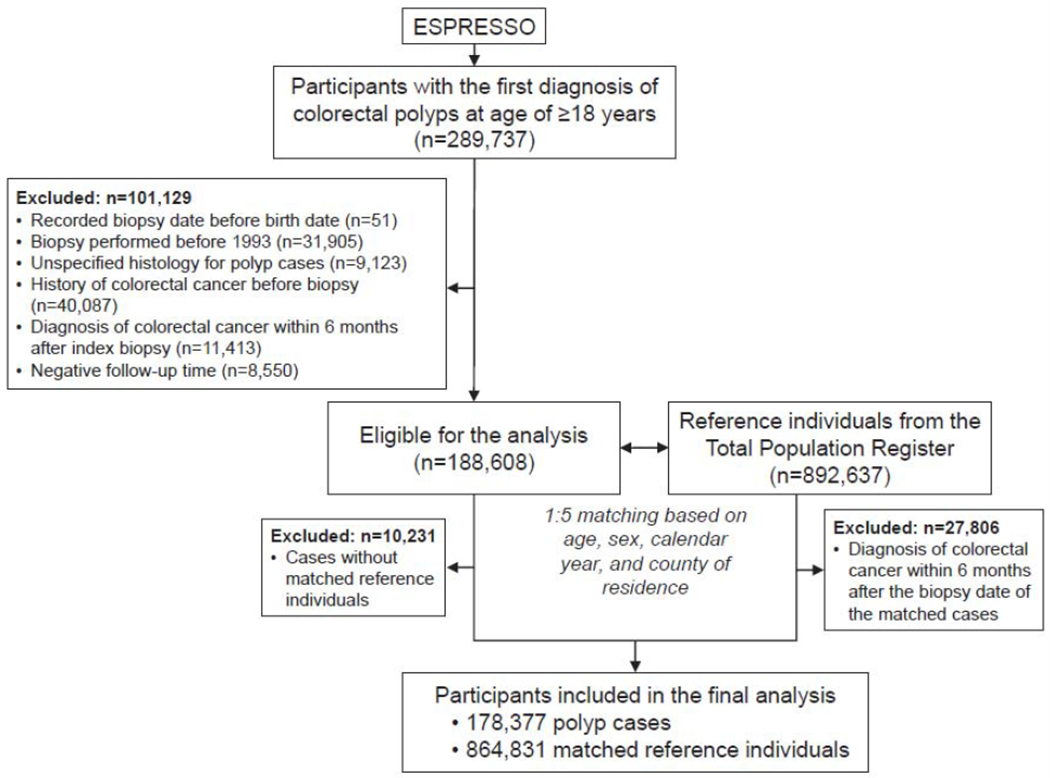

Sweden has a public health care system with universal coverage. Individual-level data from various national registries were linked based on the unique personal identity number assigned at birth to all Swedish residents.21 We used data from the ESPRESSO study (Epidemiology Strengthened by histoPathology Reports in Sweden) that includes data of gastrointestinal biopsies from all pathology departments in Sweden between 1965 and 2017.22 We identified participants with the first diagnosis of colorectal polyps aged at least 18 years in the biopsy reports (i.e., index biopsy) in ESPRESSO. We excluded individuals diagnosed before 1993, because completeness of adenoma reporting was uncertain, and SSA/Ps were miscategorized as hyperplastic polyps before more widespread adoption of this histopathologic subtype. We also excluded individuals who had a diagnosis of CRC either before or within the first 6 months after the diagnosis of the index polyp, to minimize the possibility of including individuals with synchronous cancers missed at the time of endoscopy. We further excluded individuals with unspecified histology and erroneous records on the date of biopsies and time of follow-up. Therefore, a total of 178,377 colorectal polyp cases were included in the study (see flowchart in Figure 1). For each of the polyp cases, we identified up to five matched reference individuals from the Total Population Register based on birth year, age, sex, calendar year (of biopsy), and county of residence.22 Similarly, we excluded reference individuals who were diagnosed with CRC before or within the first 6 months after the index biopsy. A total of 864,831 reference individuals from the general population were included in the final analysis. The study was approved by the Stockholm Ethics Review Board. Informed consent was waived by the board since the study was strictly register-based.23

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study participant selection. Abbreviation: ESPRESSO, Epidemiology Strengthened by histoPathology Reports in Sweden.

Polyp identification and classification

In ESPRESSO, histopathologic findings were defined by codes of morphology (a Swedish modification of the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine [SNOMED] coding system) and topography. We used topography codes of T67 (for colon) and T68 (for rectum) in combination with SNOMED codes to identify colorectal polyps.17,18 For conventional adenomas, SNOMED code of M82100 was used for tubular adenoma, M82630 for tubulovillous adenoma, M82611 for villous adenoma. Patients with more than one type of conventional adenomas were classified based on the presence of their most advanced endoscopic findings (the precedence order is defined as villous adenoma, tubulovillous adenoma, and tubular adenoma).

Serrated polyps included hyperplastic polyps and SSA/Ps. SNOMED code of M72040 was used for hyperplastic polyp. For SSA/P, we used SNOMED codes of M82160 and M82130 for records from all pathology departments except those at Aleris Medilab, for which a different code (M72041) was used (personal communication). Moreover, given the evolving nature of the diagnosis criteria for SSA/P, we attempted to account for potential underreporting in the SNOMED code by also searching various forms of “serrated” and “gtand” (part of the Swedish word for “serrated”) in the free text in the pathology report. We have validated this approach for SSA/P identification through manual review of pathology reports and patient charts in a random sample of 106 patients that were identified to have SSA/Ps based on SNOMED code and free text search in ESPRESSO. A positive predictive value of 93% (95% confidence interval [CI] 87-97%) was observed.24 Finally, patients with both conventional adenomas and serrated polyps were considered as synchronous cases. Therefore, a total of six case groups were defined for the study.

We collected location information of polyps based on the sub-codes of topography: those in the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon, or splenic flexure were classified as proximal (T671-674), polyps in the descending or sigmoid colon as distal (T675-677), and those in the rectum or rectosigmoid junction as rectal (T68x).

Ascertainment of CRC diagnosis and CRC death

CRC cases were identified from the Cancer Registry, which has recorded incident malignancies in Sweden since 1958 with high completeness. The database includes coded diagnoses based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD), date of diagnosis, and cancer staging information. We used the ICD codes to identify tumor location. Cause-of-death data were retrieved from the Cause of Death Register, which comprises all deaths among Swedish residents, whether occurring in Sweden or abroad. The causes of death were coded at Statistics Sweden using the ICD codes. For CRC, the ICD-10 codes were C18, C19 and C20, and the codes for earlier ICD versions were 153 and 154.

Assessment of covariates

We collected information on use of endoscopic examination before and after the index biopsy from the Swedish National Patient Registry, which started in 1964 with complete national coverage from 1987. We used the established procedure codes to identify colonoscopy (9011, 9023, 4688, 4689, 4674, 4684, UJF32, and UJF35) and sigmoidoscopy (9012, 4685, UJF42, and UJF45). We counted the number of endoscopies performed before and after the index biopsies. To avoid counting the diagnostic endoscopies for colorectal polyps or CRC, we excluded endoscopies performed within 30 days before and after the date of the index biopsy or CRC diagnosis.

We assessed family history based on CRC diagnosis recorded in the Cancer Registry for the parents and siblings of participants. We obtained data on education and income from the longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labor market studies, which integrates annually updated administrative information from the labor market and educational and social sectors from 1990 onward on all individuals 16 years or older registered as residents in Sweden. Information on age, sex, date of birth, and emigration status was collected form the Swedish Total Population Register maintained by Statistics Sweden.

Statistical analysis

Follow-up started at 6 months after the date of the index biopsy for polyp cases and the same date was used for their matched reference individuals. We calculated person-time of follow-up until the date of CRC diagnosis (for CRC incidence analysis only), death, emigration, or the end of the study (December 31, 2016), whichever occurred first. We plotted the Kaplan-Meier curves, and calculated cumulative risk of CRC incidence and mortality at 3, 5, 10, and 15 years. We performed the log-rank tests among cases and their matched reference individuals for each polyp subtype separately. We computed hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs of CRC incidence and mortality using stratified Cox proportional hazards model within each of the matched pairs. Therefore, the matching factors (i.e., birth year, age, sex, and county of residence) were automatically controlled for.25 We also performed adjustment for other potential confounding factors, including family history of CRC, income (quintiles), education (9 years or less, 10-12 years, >12 years, missing), number of prior clinic visits at baseline (quintiles), and number of prior colonoscopies or sigmoidoscopies at baseline (0, 1, 2 and >2). Missing indicator method was used to handle missing covariate data.

We calculated the descriptive statistics for CRC cases that occurred by polyp subtype. We also assessed the associations of polyp subtypes with CRC incidence according to cancer subsite by calculating the HRs based on a fully unconstrained approach in which the confounder effects are allowed to be different among the subgroups.26 To test whether the exposure-disease association has a trend across cancer subsites (from the proximal colon, distal colon to the rectum), we used the meta-regression method with a subgroup-specific random effect term and calculated the P for heterogeneity.26 We performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding person-years accumulated during the first year after polyp diagnosis and an exploratory analysis among patients with a combination of conventional adenomas and SSA/Ps. In addition, we estimated the HRs for CRC incidence and mortality that occurred by 3, 5, 10, and 15 years since baseline. Finally, we performed stratified analysis according to age, sex, and year of the index biopsies, and calculated the P for interaction using Wald test for the product term between stratified variable (binary or continuous) and exposure groups.

We used SAS 9.4 for all the analyses. All statistical tests were two-sided. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Role of the funding source

The study sponsors had no role in the study design; data collection; data analysis; and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the paper for publication. The corresponding author (JFL) had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Table 1 shows the basic characteristics of the study participants at the time of matching. The mean age was 58.6 years for hyperplastic polyps, 59.7 for SSA/Ps, 63.9 for tubular adenomas, 67.1 for tubulovillous adenomas, and 68.9 for villous adenomas. Compared to patients with conventional adenomas, those with hyperplastic polyps and SSA/Ps were younger and more likely to be females. Patients with SSA/Ps were diagnosed in more recent years than other polyp groups. By anatomic location, villous adenomas were more likely to be in the rectum than other polyps (1,073 [44%] of 2,431 vs. 11-38%). Most polyp patients (89-95%) did not have a history of colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy prior to index polypectomy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the reference individuals and participants with different polyp subtypes (n=1,043,208)*

| Reference individuals |

Hyperplastic polyps |

SSA/Ps | Tubular adenomas |

Tubulovillous adenomas |

Villous adenomas |

Synchronous serrated polyps and conventional adenomas |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 864,831 | 58,735 | 5,181 | 63,753 | 34,181 | 2,431 | 14,096 |

| Age, year | 63.1 (13.4) | 58.6 (13.9) | 59.7 (14.2) | 63.9 (12.9) | 67.1 (12.1) | 68.9 (11.8) | 64.4 (11.5) |

| <40, n (%) | 52,052 (6.0) | 5,970 (10.2) | 525 (10.1) | 2,807 (4.4) | 851 (2.5) | 38 (1.6) | 398 (2.8) |

| 40-49, n (%) | 88,793 (10.3) | 8,275 (14.1) | 672 (13.0) | 5,949 (9.3) | 2,062 (6.0) | 116 (4.8) | 1,057 (7.5) |

| 50-59, n (%) | 177,833 (20.6) | 14,218 (24.2) | 1,051 (20.3) | 12,378 (19.4) | 5,442 (15.9) | 332 (13.7) | 2,772 (19.7) |

| 60-69, n (%) | 264,120 (30.5) | 17,149 (29.2) | 1,613 (31.1) | 19,571 (30.7) | 10,205 (29.9) | 682 (28.1) | 5,060 (35.9) |

| 70-79, n (%) | 204,795 (23.7) | 10,139 (17.3) | 1,010 (19.5) | 16,512 (25.9) | 10,509 (30.7) | 802 (33.0) | 3,635 (25.8) |

| ≥80, n (%) | 77,238 (8.9) | 2,984 (5.1) | 310 (6.0) | 6,536 (10.3) | 5,112 (15.0) | 461 (19.0) | 1,174 (8.3) |

| Birth year | 1943.3 (14.7) | 1947.1 (15.0) | 1949.5 (15.2) | 1942.1 (14.2) | 1938.2 (13.8) | 1934.5 (13.4) | 1942.5 (12.7) |

| Female, n (%) | 442,533 (51.2) | 31,985 (54.5) | 3,001 (57.9) | 31,194 (48.9) | 17,202 (50.3) | 1,308 (53.8) | 6,547 (46.5) |

| Family history of CRC, n (%)† | 48,254 (5.6) | 5,903 (10.1) | 667 (12.9) | 5,854 (9.2) | 2,923 (8.6) | 163 (6.7) | 1,688 (12.0) |

| Year of biopsy, n (%) | |||||||

| 1993-1999 | - | 9,813 (16.7) | 450 (8.7) | 11,437 (17.9) | 7,956 (23.3) | 767 (31.6) | 1,691 (12.0) |

| 2000-2004 | - | 12,245 (20.8) | 542 (10.5) | 11,647 (18.3) | 6,186 (18.1) | 533 (21.9) | 2,582 (18.3) |

| 2005-2007 | - | 9,175 (15.6) | 494 (9.5) | 8,200 (12.9) | 3,951 (11.6) | 303 (12.5) | 2,107 (14.9) |

| 2008-2010 | - | 10,123 (17.2) | 754 (14.6) | 10,523 (16.5) | 4,834 (14.1) | 343 (14.1) | 2,542 (18.0) |

| 2011-2013 | - | 10,051 (17.1) | 1,167 (22.5) | 11,744 (18.4) | 6,030 (17.6) | 275 (11.3) | 2,792 (19.8) |

| 2014-2016 | - | 7,328 (12.5) | 1,774 (34.2) | 10,202 (16.0) | 5,224 (15.3) | 210 (8.6) | 2,382 (16.9) |

| Polyp location, n (%) | |||||||

| Colon | |||||||

| Unspecified sublocation | - | 29,103 (49.5) | 2,796 (54.0) | 38,424 (60.3) | 16,970 (49.6) | 1,043 (42.9) | 7,878 (55.9) |

| Proximal colon | - | 1,795 (3.1) | 360 (6.9) | 2,478 (3.9) | 1,118 (3.3) | 78 (3.2) | 302 (2.1) |

| Distal colon | - | 3,241 (5.5) | 239 (4.6) | 5,349 (8.4) | 2,992 (8.8) | 147 (6.0) | 572 (4.1) |

| Rectum | - | 22,214 (37.8) | 1,269 (24.5) | 15,997 (25.1) | 11,673 (34.2) | 1,073 (44.1) | 1,528 (10.8) |

| Multiple locations | - | 2,382 (4.1) | 517 (10.0) | 1,505 (2.4) | 1,428 (4.2) | 90 (3.7) | 3,816 (27.1) |

| Number of colonoscopies or sigmoidoscopies before index biopsy, n (%)‡ | |||||||

| 0 | 854,806 (98.8) | 52,835 (90.0) | 4,608 (88.9) | 58,584 (91.9) | 31,851 (93.2) | 2,300 (94.6) | 13,190 (93.6) |

| 1 | 8,074 (0.9) | 3,698 (6.3) | 362 (7.0) | 3,646 (5.7) | 1,780 (5.2) | 94 (3.9) | 680 (4.8) |

| 2 | 1,522 (0.2) | 987 (1.7) | 100 (1.9) | 856 (1.3) | 339 (1.0) | 23 (1.0) | 124 (0.9) |

| >2 | 429 (0.1) | 1,215 (2.1) | 111 (2.1) | 667 (1.1) | 211 (0.6) | 14 (0.6) | 102 (0.7) |

| Number of colonoscopies or sigmoidoscopies after index biopsy, n (%)‡ | |||||||

| 0 | 821,907 (95.0) | 43,595 (74.2) | 3,560 (68.7) | 43,561 (68.3) | 19,572 (57.3) | 1,384 (56.9) | 9,220 (65.4) |

| 1 | 28,051 (3.2) | 8,678 (14.8) | 992 (19.2) | 11,845 (18.6) | 7,975 (23.3) | 530 (21.8) | 2,847 (20.2) |

| 2 | 10,498 (1.2) | 3,141 (5.4) | 335 (6.5) | 4,538 (7.1) | 3,522 (10.3) | 251 (10.3) | 1,158 (8.2) |

| >2 | 4,375 (0.5) | 3,321 (5.7) | 294 (5.7) | 3,809 (6.0) | 3,112 (9.1) | 266 (10.9) | 871 (6.2) |

Abbreviation: SSA/Ps, sessile serrated adenoma/polyps.

Mean (standard deviation) is shown for continuous variables and percentage is shown for categorical variables.

Positive family history is defined as a diagnosis of CRC in parents or siblings prior to the study baseline.

To avoid counting the diagnostic endoscopies for colorectal polyps, we excluded endoscopies performed within 30 days before and after the date of the index biopsy or CRC diagnosis.

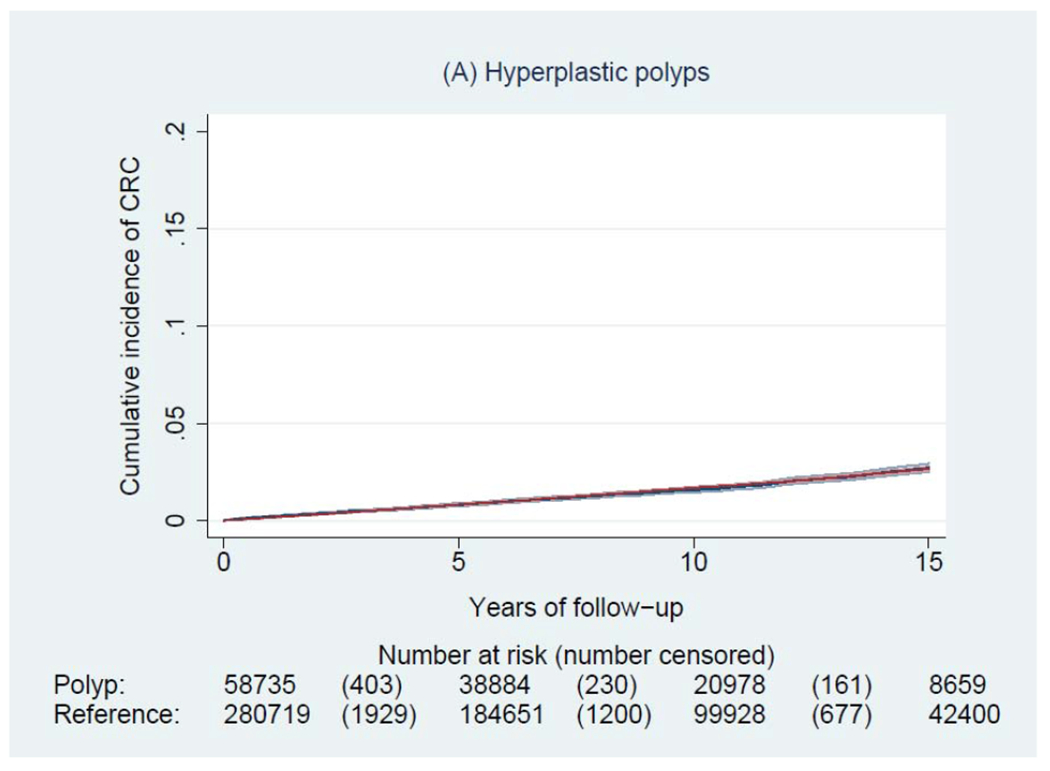

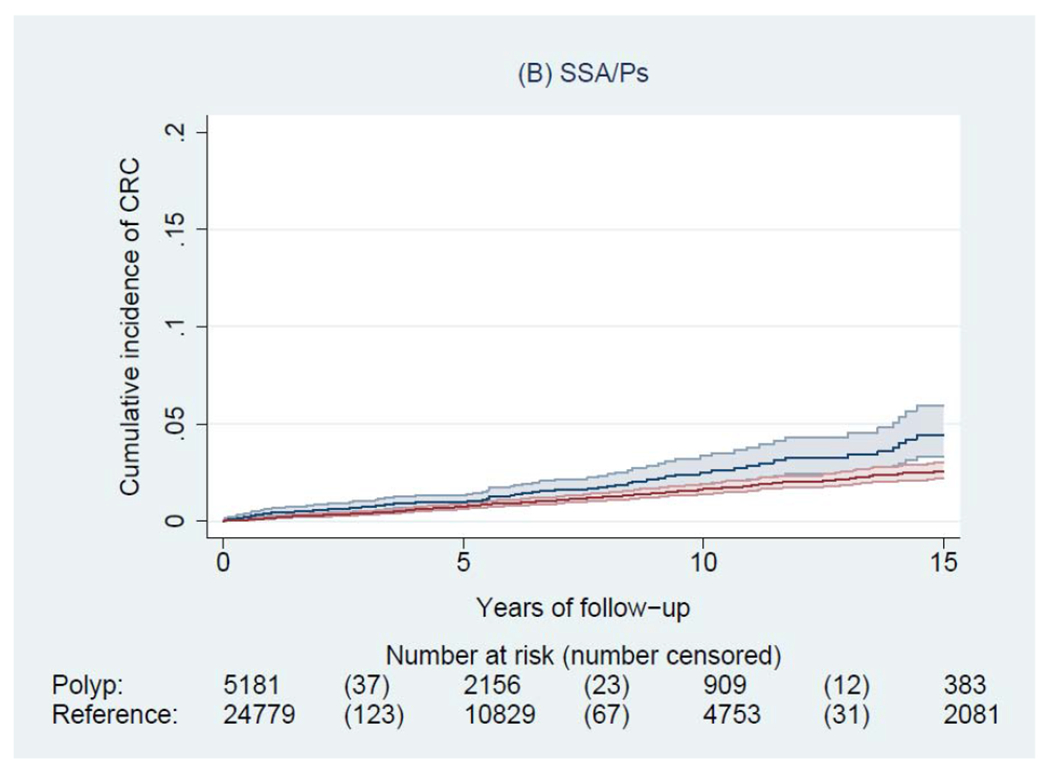

During a median of 6.6 years of follow-up (interquartile range: 3.0-11.6 years), we documented 4,278 incident CRCs and 1,269 CRC deaths among patients with a polyp, and 14,350 incident CRCs and 5,242 CRC deaths among general reference individuals. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves of CRC incidence and mortality. Detailed data on cumulative incidence at 5, 10 and 15 years are provided in appendix p1. Compared to the general reference individuals, individuals in all polyp groups except for those with hyperplastic polyps had a higher incidence of CRC (P<0.0001) but only individuals with tubulovillous and villous adenomas had higher mortality. The cumulative incidence of CRC (95% CI) at 10 years was 1.6% (1.5-1.7%) for hyperplastic polyps, 2.5% (1.9-3.3%) for SSA/Ps, 2.7% (2.5-2.9%) for tubular adenomas, 5.1% (4.8-5.4%) for tubulovillous adenomas, 8.6% (7.4-10.1%) for villous adenomas, and 3.5% (3.1-3.9%) for synchronous conventional adenomas and serrated polyps, compared with 2.1% (2.0-2.1%) for general reference individuals. For CRC mortality, compared to general reference individuals (0.7% [95% CI, 0.7-0.8%] at 10 years), a lower estimate was found for hyperplastic polyps (0.4% [95% CI, 0.4-0.5%]) and a higher estimate for SSA/Ps (1.0% [95% CI, 0.6-1.5%]), tubulovillous adenomas (1.6% [95% CI, 1.5-1.8%]), and villous adenomas (3.5% [95% CI, 2.7-4.5%]).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of cumulative incidence (A-F) and mortality (G-L) of colorectal cancer (CRC) and 95% pointwise confidence bands in each of the polyp groups (blue) and their matched reference individuals (red). The P value for log-rank test for CRC incidence was 0.62 for hyperplastic polyps, <0.0001 for SSA/Ps, <0.0001 for tubular adenomas, <0.0001 for tubulovillous adenomas, <0.0001 for villous adenomas, and <0.0001 for synchronous serrated polyps and conventional adenomas; for CRC mortality was 0.03 for hyperplastic polyps, 0.07 for SSA/Ps, 0.38 for tubular adenomas, <0.0001 for tubulovillous adenomas, <0.0001 for villous adenomas, and 0.12 for synchronous serrated polyps and conventional adenomas. Abbreviation: SSA/Ps, sessile serrated adenoma/polyps.

Table 2 shows the association of different polyp subtypes with CRC incidence and mortality. After adjustment for potential confounders, a positive association with CRC incidence was observed for all polyp subtypes, with the HR (95% CI, P value) of 1.11 (1.02-1.22, P=0.02) for hyperplastic polyps, 1.41 (1.30-1.52, P<0.0001) for tubular adenomas, 1.77 (1.34-2.34, P<0.0001) for SSA/Ps, 2.56 (2.36-2.78, P<0.0001) for tubulovillous adenomas, to 3.82 (3.07-4.76, P<0.0001) for villous adenomas. For CRC mortality, a positive association was found for SSA/Ps (multivariable HR, 1.74, 95% CI, 1.08-2.79, P=0.02), tubulovillous adenomas (1.95, 1.69-2.24, P<0.0001), and villous adenomas (3.45, 2.40-4.95, P<0.0001), but not hyperplastic polyps (0.90, 0.76-1.06, P=0.20) or tubular adenomas (0.97, 0.84-1.12, P=0.63). When examined by time since baseline, the associations were generally stronger for earlier years than for later years after polyp diagnosis (appendix p1). For example, the HR of CRC mortality associated with SSA/Ps decreased from 4.10 (95% CI, 1.69-9.98) at 3 years and to 1.91 (1.17-3.13) at 15 years of polyp diagnosis.

Table 2.

Association between polyp subtypes and incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer

| Reference individuals |

Hyperplastic polyps |

SSA/Ps | Tubular adenomas |

Tubulovillous adenomas |

Villous adenomas |

Synchronous serrated polyps and conventional adenomas |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal cancer incidence | |||||||

| No. of events | 14,350 | 878 | 77 | 1,361 | 1,406 | 176 | 380 |

| No. of person-years | 6,780,775 | 492,177 | 28,669 | 475,543 | 250,726 | 18,884 | 97,315 |

| Incidence rate (per 10,000 person-years) | 21.2 | 17.8 | 26.9 | 28.6 | 56.1 | 93.2 | 39.0 |

| HR (95% CI)* | 1 (ref) | 0.97 (0.90-1.05) | 1.54 (1.17-2.02) | 1.23 (1.15-1.31) | 2.26 (2.11-2.42) | 3.38 (2.73-4.18) | 1.58 (1.40-1.79) |

| P* | 0.51 | 0.002 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| HR (95% CI)† | 1 (ref) | 1.11 (1.02-1.22) | 1.77 (1.34-2.34) | 1.41 (1.30-1.52) | 2.56 (2.36-2.78) | 3.82 (3.07-4.76) | 1.84 (1.61-2.10) |

| P† | 0.02 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Colorectal cancer mortality | |||||||

| No. of events | 5,242 | 253 | 26 | 366 | 461 | 67 | 96 |

| No. of person-years | 6,836,937 | 496,164 | 28,968 | 482,787 | 258,013 | 19,971 | 99,088 |

| Mortality rate (per 10,000 person-years) | 7.7 | 5.1 | 9.0 | 7.6 | 17.9 | 33.5 | 9.7 |

| HR (95% CI)* | 1 (ref) | 0.83 (0.72-0.95) | 1.61 (1.01-2.56) | 0.89 (0.79-1.01) | 1.83 (1.63-2.06) | 3.30 (2.33-4.66) | 1.11 (0.88-1.41) |

| P* | 0.008 | 0.05 | 0.06 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.37 | |

| HR (95% CI)† | 1 (ref) | 0.90 (0.76-1.06) | 1.74 (1.08-2.79) | 0.97 (0.84-1.12) | 1.95 (1.69-2.24) | 3.45 (2.40-4.95) | 1.20 (0.93-1.55) |

| P† | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.63 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.16 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, Hazard ratio; SSA/Ps, sessile serrated adenoma/polyps.

The matching factors including birth year, age, sex, and county of residence were automatically adjusted for by the stratified Cox regression.

Further adjusted for family history of CRC (yes, no), income levels (quintiles), education (9 years or less, 10-12 years, >12 years, missing), number of prior clinic visits at baseline (quintiles), and number of prior colonoscopies or sigmoidoscopies at baseline (0, 1, 2 and >2).

In a sensitivity analysis, we excluded person-years accumulated during the first year after polyp diagnosis. The results were largely unchanged except for modest attenuation for villous adenomas in relation to CRC incidence (HR, 2.70, 95% CI, 2.11-3.46) (data only shown in the text). Given prior data indicating a higher risk of polyp recurrence in patients with a combination of conventional adenomas and SSA/Ps,27 we performed an exploratory analysis in these patients (n=1,817) and found an HR of 2.15 (95% CI, 1.51-3.05) for CRC incidence and 1.71 (0.91-3.21) for CRC mortality (data only shown in the text).

Figure 3 and appendix p2 show characteristics of incident CRC. The subsite distribution of CRC varied across polyp subtypes, with a higher proportion of proximal colon cancer in hyperplastic polyps (501 [57%] of 878) and SSA/Ps (40 [52%] of 77) than conventional adenomas (30-46%). The mean time interval between polyp diagnosis and CRC diagnosis was highest for hyperplastic polyps (7.4 years), decreased to 6.1 years for SSA/Ps, 5.2 years for tubulovillous adenomas, and achieved its lowest for villous adenomas (4.1 years). The mean age at CRC diagnosis ranged from 70.8 years for SSA/Ps to 74.6 years for tubulovillous adenomas and 74.1 years for villous adenomas.

Figure 3.

Distribution of subsite (A), age and time interval (B) of colorectal cancer diagnosis after polypectomy in each polyp group. P<0.0001 for tests across polyp groups by subsite, time interval, and age at colorectal cancer diagnosis. Abbreviation: SSA/Ps, sessile serrated adenoma/polyps.

Table 3 shows the results of subgroup analysis. When CRC cases were classified by cancer subsite, we found that hyperplastic polyps, SSA/Ps, tubular adenomas and synchronous polyps were more strongly associated with higher risk of proximal colon cancer, whereas tubulovillous and villous adenomas were more strongly associated with rectal cancer.

Table 3.

Association between polyp subtypes and incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) by cancer subsite

| Reference individuals |

Hyperplastic polyps |

SSA/Ps | Tubular adenomas |

Tubulovillous adenomas |

Villous adenomas |

Synchronous serrated polyps and conventional adenomas |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal colon cancer | |||||||

| No. of cases | 5040 | 501 | 40 | 622 | 535 | 52 | 190 |

| HR (95% CI)* | 1 (ref) | 2.14 (1.90-2.42) | 2.77 (1.84-4.18) | 2.08 (1.86-2.33) | 3.27 (2.88-3.71) | 3.69 (2.52-5.42) | 3.21 (2.63-3.91) |

| P* | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Distal colon cancer | |||||||

| No. of cases | 4061 | 175 | 12 | 291 | 286 | 29 | 95 |

| HR (95% CI)* | 1 (ref) | 0.81 (0.68-0.97) | 1.11 (0.57-2.18) | 1.18 (1.02-1.36) | 2.35 (2.01-2.74) | 2.70 (1.68-4.34) | 1.79 (1.40-2.30) |

| P* | 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.02 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Rectal cancer | |||||||

| No. of cases | 4687 | 151 | 22 | 350 | 514 | 91 | 69 |

| HR (95% CI)* | 1 (ref) | 0.62 (0.52-0.74) | 1.73 (1.05-2.84) | 1.28 (1.12-1.46) | 3.45 (3.04-3.92) | 7.49 (5.28-10.63) | 1.12 (0.85-1.48) |

| P* | <0.0001 | 0.03 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.43 | |

| P for heterogeneity† | <0.0001 | 0.05 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, Hazard ratio; SSA/Ps, sessile serrated adenoma/polyps.

Adjusted for family history of CRC (yes, no), income levels (quintiles), education (9 years or less, 10-12 years, >12 years, missing), number of prior clinic visits at baseline (quintiles), and number of prior colonoscopies or sigmoidoscopies at baseline (0, 1, 2 and >2). The matching factors including birth year, age, sex, and county of residence were automatically adjusted for by the stratified Cox regression.

P for heterogeneity was calculated to assess whether there was a trend across the ordinal subtypes in the polyp-CRC association using the meta-regression method with a subtype-specific random effect term.

Appendix p3 shows the stratified association with CRC incidence. A generally stronger association was found for younger than for older individuals, for women than men, and for polyps diagnosed before than after 2003. For CRC mortality, no large difference across these strata was observed, except for an age-varying association for SSA/Ps (P for interaction=0.008), that were associated increased mortality among individuals older than 65 years but lower mortality among those younger than 65 years (see appendix p4). However, given the large number of statistical tests, these results should be interpreted cautiously.

Discussion

Leveraging data from a nationwide histopathology cohort in Sweden, we found that compared to individuals from the general population, patients with any polyps had a higher CRC incidence, and those with SSA/Ps, tubulovillous adenomas, and villous adenomas had a higher CRC mortality. The risk elevation increased by advanced histology for both conventional adenomas (from tubular, tubulovillous to villous adenomas) and serrated polyps (from hyperplastic polyps to SSA/Ps), whereas the time interval between polyp diagnosis and subsequent CRC diagnosis decreased by advanced histology. Moreover, patients with hyperplastic polyps and SSA/Ps were more likely to develop proximal colon cancer than those with conventional adenomas. Our findings provide novel data on the long-term risk of CRC after polypectomy in a largely screening-naïve population.

Consistent with our findings, most prior studies of conventional adenomas found that patients with advanced adenomas had a higher incidence and mortality of CRC than the general population or individuals with no polyps.12,13,17–20 On the other hand, the findings on small tubular adenomas remain inconsistent, with a lower CRC risk observed in some17–20 but not other studies12–14. In the current study, tubular adenomas were associated with higher CRC incidence, but not CRC mortality. However, because of the lack of information on polyp size, we were unable to distinguish small from large tubular adenomas, the latter of which have been the predominant subtype linked to higher CRC risk.13 It is possible that our observed association for CRC incidence in tubular adenoma was driven by the predominantly large tubular adenomas, especially since there was no organized screening in Sweden during most of the study period and most endoscopies were likely performed to evaluate symptoms which are more commonly associated with large polyps. Moreover, we found that the increased CRC risk associated with tubular adenomas was restricted to adenoma cases diagnosed before but not after 2003. This time trend may reflect increased utilization of surveillance and improved quality of endoscopic examination over time. Indeed, the adenoma detection rate, a key quality indicator for colonoscopy, has been inversely associated with the risk of post-colonoscopy CRC.28 A lower rate of post-colonoscopy CRC has been observed following the introduction of the colonoscopy quality improvement initatives.29 Further studies quantifying the influence of changes in colonoscopy quality on the risk of post-polypectomy CRC are warranted.

In contrast to conventional adenomas, the natural history of serrated polyps is less understood.So far only 3 prospective studies have examined the long-term incidence of CRC in individuals with serrated polyps.13,15,16 Two of them13,15 did not distinguish hyperplastic polyps from SSA/Ps due to lack of consensus in the diagnostic criteria for SSA/Ps during most of the study period, and found an increased risk of CRC associated with large serrated polyps, which have been proposed as an indicator for SSA/Ps. Another nationwide case-control study nested among individuals who had received colonoscopies in Denmark found an increased CRC risk among patients with SSA/Ps compared to those with no polyp.16 Consistent with these findings, we found that both hyperplastic polyps and SSA/Ps were associated with higher risk of CRC. The positive association for hyperplastic polyps is at least partly due to misdiagnosis of true SSA/Ps, as indicated by 1) the much stronger association for SSA/Ps than hyperplastic polyps; 2) the lack of association for hyperplastic polyps diagnosed since 2003 when SSA/Ps became more widely recognized; and 3) the lack of association for hyperplastic polyps with CRC mortality.

Also, in support of the role of serrated polyps in the development of proximal colon cancer,3,16 we found a higher proportion of diagnosis of proximal colon cancer among patients with hyperplastic polyps (57%) and SSA/Ps (52%) than adenomas (30-46%), and that the increased cancer risk for hyperplastic polyps was restricted to the proximal colon (HR, 1.91). Moreover, we reported a novel observation for an increased mortality of CRC associated with SSA/Ps (HR, 1.74), particularly within the first 3 years after diagnosis (HR, 4.10). Given the subtle endoscopic appearance, SSA/Ps are more likely to be missed and incompletely removed than conventional adenomas. Also, the molecular features of SSA/Ps (e.g., BRAF mutation) may induce more rapid malignant transformation, within as soon as 8 months.30 As a result, SSA/Ps have been shown to contribute disproportionately to post-colonoscopy cancers.4 Consistent with these data, our findings suggest the importance of surveillance and improved colonoscopy performance for prevention of post-colonoscopy CRC associated with SSA/Ps.3 On the other hand, patients with hyperplastic polyps did not show any increase in CRC mortality and thus may not warrant intensive surveillance, although we were unable to specifically assess large or proximal hyperplastic polyps.

Our study has several strengths, including the nationwide population-based design, large sample size, long-term and complete follow-up, high validity of the cancer register, examination of both CRC incidence and mortality, as well as the ability to adjust for factors that may influence CRC risk. Some limitations of our study need to be noted as well. First, we used individuals drawn from the general population as the reference group. Thus, the CRC risk in relation to polyps may have been underestimated due to the established benefit of endoscopic examination itself and the possibility that some reference individuals may have had undiagnosed polyps because of lack of colonoscopies. On the other hand, because polyp patients are more likely to receive surveillance endoscopy, there is a risk of detection bias driving the effect estimates for CRC incidence. This may be another explanation for our observation that hyperplastic polyps and tubular adenomas were associated with increased risk of CRC incidence but not CRC mortality, which is not affected by detection bias. Second, we lacked information on other factors that may influence CRC risk, including polyp size and multiplicity, quality and indication of endoscopy, and lifestyle risk factors (e.g., smoking, obesity, and diet). Of note, villous histology has been associated with large size and high-grade dysplasia. Third, the endoscopy data were based on procedure coding and subject to measurement error. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to populations in which screening endoscopy is common.

In conclusion, patients with any polyp subtype had a higher risk of CRC incidence than the general individuals in the largely screening-naïve population. The risk elevation increased with advanced histology for both conventional adenomas and serrated polyps. In contrast, the risk of CRC mortality was increased only among patients with SSA/Ps, tubulovillous adenomas and villous adenomas. Our findings suggest that patients with the latter three lesions may benefit from colonoscopy surveillance.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed for articles published in English between Jan 1, 1990, and Sep 23, 2019, using the terms “colorectal cancer” and “colorectal polyp” and “endoscopy” or “colonoscopy” or “sigmoidoscopy”, and “cohort”. We found that most previous studies examined recurrence of colorectal neoplasia as the primary outcome and a few examined colorectal cancer as the endpoint. Also, we only found one study that assessed the long-term risk of colorectal cancer incidence after diagnosis of conventional adenomas and serrated polyps, but the study was unable to distinguish between hyperplastic polyps and SSA/Ps. No study has yet examined colorectal cancer mortality after removal of different subtypes of polyps.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively characterize colorectal cancer incidence and mortality in relation to different histological subtypes of polyps in a largely screening-naïve population. Compared to matched reference individuals, patients with any polyp subtype had a higher colorectal cancer incidence. The risk elevation appeared to increase with advanced histology of the index polyp. For colorectal cancer mortality, an increased risk was found among individuals with sessile serrated adenoma/polyps, tubulovillous adenomas, and villous adenomas, but not those with hyperplastic polyps or tubular adenomas.

Implications of all the available evidence

The results of the current study indicate that individuals with any polyp subtype had a higher risk of colorectal cancer, and those with SSA/Ps, tubulovillous adenomas, and villous adenomas had a higher CRC mortality than general individuals. Further studies are needed to examine the impact of colonoscopy surveillance on prevention of colorectal cancer.

Acknowledgement

We appreciate Bjorn Roelstraete and Dr. Molin Wang for their statistical support.

Conflict of interest:

Dr. Staller reports personal fees from Shire, grants from Takeda, personal fees from Synergy, personal fees from Bayer, grants from AstraZeneca, grants from Gelesis, outside the submitted work. Dr. Chan reports grants from Bayer Pharma AG, personal fees from Pfizer Inc., personal fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Boeringher Ingelheim, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Ludvigsson coordinates a study on behalf of the Swedish IBD quality register (SWIBREG) and that study has received funding from Janssen corporation. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Funding statement

The work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH, R00 CA215314 to MS), American Cancer Society (MRSG-17-220-01-NEC), American Gastroenterological Association (Research Scholar Award to KS), and Union for International Cancer Control (Yamagiwa-Yoshida Award YY2/17/554363). ATC is a Stuart and Suzanne Steele MGH Research Scholar. None of the authors are employed by NIH.

The study sponsors had no role in the study design; data collection; data analysis; and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

The corresponding author (JFL) had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

List of abbreviations:

- CI

confidence interval

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- ESPRESSO

Epidemiology Strengthened by histoPathology Reports in Sweden

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- SNOMED

Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine

- SSA/P

sessile serrated adenoma/polyp

- TSA

traditional serrated adenoma

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Collaborators GBDCC. The global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 4(12): 913–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 2010; 138(6): 2088–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.JE IJ, Vermeulen L, Meijer GA, Dekker E. Serrated neoplasia-role in colorectal carcinogenesis and clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 12(7): 401–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweetser S, Jones A, Smyrk TC, Sinicrope FA. Sessile Serrated Polyps are Precursors of Colon Carcinomas With Deficient DNA Mismatch Repair. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 14(7): 1056–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, et al. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002). Gut 2010; 59(5): 666–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2012; 143(3): 844–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atkin WS, Valori R, Kuipers EJ, et al. European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. First Edition--Colonoscopic surveillance following adenoma removal. Endoscopy 2012; 44 Suppl 3: SE151–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107(9): 1315–29; quiz 4,, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hassan C, Quintero E, Dumonceau JM, et al. Post-polypectomy colonoscopy surveillance: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy 2013; 45(10): 842–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.East JE, Atkin WS, Bateman AC, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology position statement on serrated polyps in the colon and rectum. Gut 2017; 66(7): 1181–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saini SD, Kim HM, Schoenfeld P. Incidence of advanced adenomas at surveillance colonoscopy in patients with a personal history of colon adenomas: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 64(4): 614–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Click B, Pinsky PF, Hickey T, Doroudi M, Schoen RE. Association of Colonoscopy Adenoma Findings With Long-term Colorectal Cancer Incidence. JAMA 2018; 319(19): 2021–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X, Hang D, Wu K, et al. Long-term Risk of Colorectal Cancer After Removal of Conventional Adenomas and Serrated Polyps. Gastroenterology 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JK, Jensen CD, Levin TR, et al. Long-term Risk of Colorectal Cancer and Related Death After Adenoma Removal in a Large, Community-based Population. Gastroenterology 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holme O, Bretthauer M, Eide TJ, et al. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer in individuals with serrated polyps. Gut 2015; 64(6): 929–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erichsen R, Baron JA, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, et al. Increased Risk of Colorectal Cancer Development Among Patients With Serrated Polyps. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(4): 895–902 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emilsson L, Loberg M, Bretthauer M, et al. Colorectal cancer death after adenoma removal in Scandinavia. Scand J Gastroenterol 2017; 52(12): 1377–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loberg M, Kalager M, Holme O, Hoff G, Adami HO, Bretthauer M. Long-term colorectal-cancer mortality after adenoma removal. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(9): 799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cottet V, Jooste V, Fournel I, Bouvier AM, Faivre J, Bonithon-Kopp C. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer after adenoma removal: a population-based cohort study. Gut 2012; 61(8): 1180–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wieszczy P, Kaminski MF, Franczyk R, et al. Colorectal Cancer Incidence and Mortality After Removal of Adenomas During Screening Colonoscopies. Gastroenterology 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2009; 24(11): 659–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludvigsson JF, Lashkariani M. Cohort profile: ESPRESSO (Epidemiology Strengthened by histoPathology Reports in Sweden). Clin Epidemiol 2019; 11: 101–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludvigsson JF, Haberg SE, Knudsen GP, et al. Ethical aspects of registry-based research in the Nordic countries. Clinical epidemiology 2015; 7: 491–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bozorg SR, Song M, Emilsson L, Ludvigsson JF. Validation of Serrated Polyps (SPs) in Swedish Pathology Registers. BMC Gastroenterology 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sjolander A, Greenland S. Ignoring the matching variables in cohort studies - when is it valid and why? Stat Med 2013; 32(27): 4696–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang M, Spiegelman D, Kuchiba A, et al. Statistical methods for studying disease subtype heterogeneity. Stat Med 2016; 35(5): 782–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson JC, Butterly LF, Robinson CM, Weiss JE, Amos C, Srivastava A. Risk of Metachronous High-Risk Adenomas and Large Serrated Polyps in Individuals With Serrated Polyps on Index Colonoscopy: Data From the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry. Gastroenterology 2018; 154(1): 117–27 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(14): 1298–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burr NE, Derbyshire E, Taylor J, et al. Variation in post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer across colonoscopy providers in English National Health Service: population based cohort study. BMJ 2019; 367: l6090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oono Y, Fu K, Nakamura H, et al. Progression of a sessile serrated adenoma to an early invasive cancer within 8 months. Dig Dis Sci 2009; 54(4): 906–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.